Book Serendipity, Mid-June through August

I call it “Book Serendipity” when two or more books that I read at the same time or in quick succession have something in common – the more bizarre, the better. This is a regular feature of mine every couple of months. Because I usually have 20–30 books on the go at once, I suppose I’m more prone to such incidents. People frequently ask how I remember all of these coincidences. The answer is: I jot them down on scraps of paper or input them immediately into a file on my PC desktop; otherwise, they would flit away!

The following are in roughly chronological order.

- A description of the Y-shaped autopsy scar on a corpse in Pet Sematary by Stephen King and A Truce that Is Not Peace by Miriam Toews.

- Charlie Chaplin’s real-life persona/behaviour is mentioned in The Quiet Ear by Raymond Antrobus and Greyhound by Joanna Pocock.

- The manipulative/performative nature of worship leading is discussed in Don’t Forget We’re Here Forever by Lamorna Ash and Jarred Johnson’s essay in the anthology Queer Communion: Religion in Appalachia. I read one scene right after the other!

- A discussion of the religious impulse to celibacy in Don’t Forget We’re Here Forever by Lamorna Ash and The Dry Season by Melissa Febos.

- Hanif Kureishi has a dog named Cairo in Shattered; Amelia Thomas has a son by the same name in What Sheep Think About the Weather.

- A pilgrimage to Virginia Woolf’s home in The Dry Season by Melissa Febos and Writing Creativity and Soul by Sue Monk Kidd.

- Water – Air – Earth divisions in the Nature Matters (ed. Mona Arshi and Karen McCarthy Woolf) and Moving Mountains (ed. Louise Kenward) anthologies.

The fact that humans have two ears and one mouth and so should listen more than they talk is mentioned in What Sheep Think about the Weather by Amelia Thomas and The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese.

The fact that humans have two ears and one mouth and so should listen more than they talk is mentioned in What Sheep Think about the Weather by Amelia Thomas and The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese.

- Inappropriate sexual comments made to female bar staff in The Most by Jessica Anthony and Isobel Anderson’s essay in the Moving Mountains (ed. Louise Kenward) anthology.

- Charlie Parker is mentioned in The Most by Jessica Anthony and The Quiet Ear by Raymond Antrobus.

- The metaphor of an ark for all the elements that connect one to a language and culture was used in Chopping Onions on My Heart by Samantha Ellis, which I read earlier in the year, and then again in The Quiet Ear by Raymond Antrobus.

- A scene of first meeting their African American wife (one of the partners being a poet) and burning a list of false beliefs in The Dry Season by Melissa Febos and The Quiet Ear by Raymond Antrobus.

- The Kafka quote “a book must be the axe for the frozen sea inside us” appears in Shattered by Hanif Kureishi and Writing Creativity and Soul by Sue Monk Kidd. They also both quote Dorothea Brande on writing.

- The simmer dim (long summer light) in Shetland is mentioned in Storm Pegs by Jen Hadfield and Sally Huband’s piece in the Moving Mountains (ed. Louise Kenward) anthology (not surprising as they both live in Shetland!).

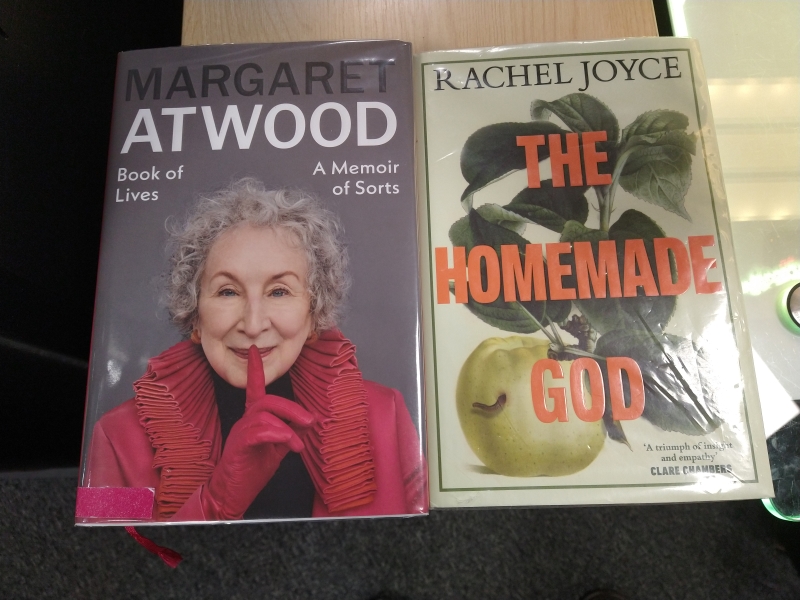

- A restaurant applauds a proposal or the news of an engagement in The Homemade God by Rachel Joyce and Likeness by Samsun Knight.

- Noticing that someone ‘isn’t there’ (i.e., their attention is elsewhere) in Woodworking by Emily St. James and Palaver by Bryan Washington.

- I was reading Leaving Atlanta by Tayari Jones and Leaving Church by Barbara Brown Taylor – which involves her literally leaving Atlanta to be the pastor of a country church – at the same time. (I was also reading Leave the World Behind by Rumaan Alam.)

- A mention of an adolescent girl wearing a two-piece swimsuit for the first time in Leave the World Behind by Rumaan Alam, The Summer I Turned Pretty by Jenny Han, and The Stirrings by Catherine Taylor.

- A discussion of John Keats’s concept of negative capability in My Little Donkey by Martha Cooley and What Sheep Think About the Weather by Amelia Thomas.

- A mention of JonBenét Ramsey in Leave the World Behind by Rumaan Alam and the new introduction to Leaving Atlanta by Tayari Jones.

- A character drowns in a ditch full of water in Leaving Atlanta by Tayari Jones and The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese.

A girl dares to question her grandmother for talking down the girl’s mother (i.e., the grandmother’s daughter-in-law) in Cekpa by Leah Altman and Leaving Atlanta by Tayari Jones.

A girl dares to question her grandmother for talking down the girl’s mother (i.e., the grandmother’s daughter-in-law) in Cekpa by Leah Altman and Leaving Atlanta by Tayari Jones.

- A woman who’s dying of stomach cancer in The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese and Book of Exemplary Women by Diana Xin.

- A woman’s genitals are referred to as the “mons” in Leave the World Behind by Rumaan Alam and The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese.

- A girl doesn’t like her mother asking her to share her writing with grown-ups in People with No Charisma by Jente Posthuma and one story of Book of Exemplary Women by Diana Xin.

- A girl is not allowed to walk home alone from school because of a serial killer at work in the area, and is unprepared for her period so lines her underwear with toilet paper instead in Leaving Atlanta by Tayari Jones and The Stirrings by Catherine Taylor.

When I interviewed Amy Gerstler about her poetry collection Is This My Final Form?, she quoted a Walt Whitman passage about animals. I found the same passage in What Sheep Think About the Weather by Amelia Thomas.

When I interviewed Amy Gerstler about her poetry collection Is This My Final Form?, she quoted a Walt Whitman passage about animals. I found the same passage in What Sheep Think About the Weather by Amelia Thomas.

- A character named Stefan in The Dime Museum by Joyce Hinnefeld and Palaver by Bryan Washington.

- A father who is a bad painter in The Dime Museum by Joyce Hinnefeld and The Homemade God by Rachel Joyce.

- The goddess Minerva is mentioned in The Dime Museum by Joyce Hinnefeld and The Stirrings by Catherine Taylor.

- A woman finds lots of shed hair on her pillow in In Late Summer by Magdalena Blažević and The Dig by John Preston.

An Italian man who only uses the present tense when speaking in English in The Homemade God by Rachel Joyce and Beautiful Ruins by Jess Walter.

An Italian man who only uses the present tense when speaking in English in The Homemade God by Rachel Joyce and Beautiful Ruins by Jess Walter.

- The narrator ponders whether she would make a good corpse in People with No Charisma by Jente Posthuma and Terminal Surreal by Martha Silano. The former concludes that she would, while the latter struggles to lie still during savasana (“Corpse Pose”) in yoga – ironic because she has terminal ALS.

- Harry the cat in The Wedding People by Alison Espach; Henry the cat in Calls May Be Recorded by Katharina Volckmer.

- The protagonist has a blood test after rapid weight gain and tiredness indicate thyroid problems in Voracious by Małgorzata Lebda and The Stirrings by Catherine Taylor.

- It’s said of an island that nobody dies there in Somebody Is Walking on Your Grave by Mariana Enríquez and Beautiful Ruins by Jess Walter.

- A woman whose mother died when she was young and whose father was so depressed as a result that he was emotionally detached from her in The Wedding People by Alison Espach and People with No Charisma by Jente Posthuma.

A scene of a woman attending her homosexual husband’s funeral in The Homemade God by Rachel Joyce and Novel About My Wife by Emily Perkins.

A scene of a woman attending her homosexual husband’s funeral in The Homemade God by Rachel Joyce and Novel About My Wife by Emily Perkins.

- There’s a ghost in the cellar in In Late Summer by Magdalena Blažević, The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese and Book of Exemplary Women by Diana Xin.

- Mention of harps / a harpist in The Wedding People by Alison Espach, The Homemade God by Rachel Joyce, and What Mennonite Girls Are Good For by Jennifer Sears.

- “You use people” is an accusation spoken aloud in The Dry Season by Melissa Febos and Beautiful Ruins by Jess Walter.

- Let’s not beat around the bush: “I want to f*ck you” is spoken aloud in The Wedding People by Alison Espach and Novel About My Wife by Emily Perkins; “Want to/Wanna f*ck?” is also in The Wedding People by Alison Espach and in Bigger by Ren Cedar Fuller.

A young woman notes that her left breast is larger in Voracious by Małgorzata Lebda and Woodworking by Emily St. James. (And a girl fondles her left breast in one story of Book of Exemplary Women by Diana Xin.)

A young woman notes that her left breast is larger in Voracious by Małgorzata Lebda and Woodworking by Emily St. James. (And a girl fondles her left breast in one story of Book of Exemplary Women by Diana Xin.)

- A shawl is given as a parting gift in How to Cook a Coyote by Betty Fussell and one story of What Mennonite Girls Are Good For by Jennifer Sears.

- The author has Long Covid in Alec Finlay’s essay in the Moving Mountains anthology, and Pluck by Adam Hughes.

- An old woman applies suncream in Kate Davis’s essay in the Moving Mountains anthology, and How to Cook a Coyote by Betty Fussell.

- There’s a leper colony in What Mennonite Girls Are Good For by Jennifer Sears and The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese.

- There’s a missionary kid in South America in Bigger by Ren Cedar Fuller and What Mennonite Girls Are Good For by Jennifer Sears.

A man doesn’t tell his wife that he’s lost his job in Novel About My Wife by Emily Perkins and The Summer House by Philip Teir.

A man doesn’t tell his wife that he’s lost his job in Novel About My Wife by Emily Perkins and The Summer House by Philip Teir.

- A teen brother and sister wander the woods while on vacation with their parents in Leave the World Behind by Rumaan Alam and The Summer House by Philip Teir.

- Using a famous fake name as an alias for checking into a hotel in one story of Single, Carefree, Mellow by Katherine Heiny and Seascraper by Benjamin Wood.

- A woman punches someone in the chest in the title story of Dreams of Dead Women’s Handbags by Shena Mackay and Novel About My Wife by Emily Perkins.

What’s the weirdest reading coincidence you’ve had lately?

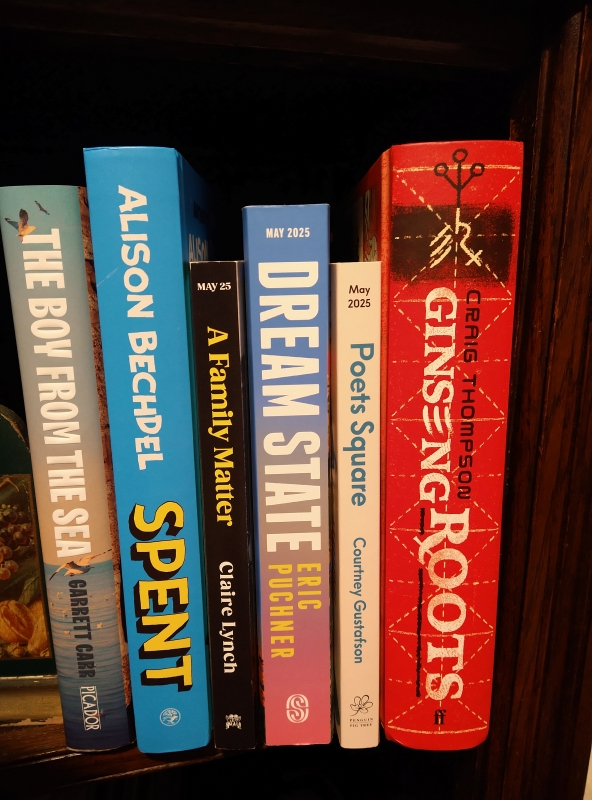

The Boy from the Sea by Garrett Carr: I was entranced by this story of an Irish family in the 1970s–80s: Ambrose, a fisherman left behind by technology; his wife Christine, walked all over by her belligerent father and sister; their son Declan, a budding foodie; and the title character, Brendan, a foundling they adopt and raise. Narrated by a chorus of village voices, this debut has the heart of Claire Keegan and the humour of Paul Murray. It reimagines biblical narratives, too: Cain and Abel, Jacob and Esau (brotherly rivalry!); Job and more.

The Boy from the Sea by Garrett Carr: I was entranced by this story of an Irish family in the 1970s–80s: Ambrose, a fisherman left behind by technology; his wife Christine, walked all over by her belligerent father and sister; their son Declan, a budding foodie; and the title character, Brendan, a foundling they adopt and raise. Narrated by a chorus of village voices, this debut has the heart of Claire Keegan and the humour of Paul Murray. It reimagines biblical narratives, too: Cain and Abel, Jacob and Esau (brotherly rivalry!); Job and more.