Women’s Prize 2024: Longlist Predictions vs. Wishes

This is the fourth year in a row that I’ve made predictions for the Women’s Prize longlist (the real thing comes out on Tuesday, 6 p.m. GMT). It shows how invested I’ve become in this prize in recent years. Like I did last year, I’ll give predictions, then wishes (no overlap this time!). My wishes are based on what I have already read and want to read. Although I kept tabs on publishers and ‘free entries’ for previous winners and shortlistees, I didn’t let quotas determine my selections. And while I kept in mind that there are two novelists on the judging panel, I don’t know enough about any of these judges’ taste to be able to tailor my predictions. My only thought was that they will probably appreciate good old-fashioned storytelling … but also innovative storytelling.

(There are two books – The List of Suspicious Things by Jennie Godfrey (= Joanna Cannon?) and Jaded by Ela Lee (this year’s Queenie) – that I only heard about as I was preparing this post and seem pretty likely, but I felt that it would be cheating for me to include them.)

Predictions

The Three of Us, Ore Agbaje-Williams

The Future, Naomi Alderman

The Storm We Made, Vanessa Chan

Penance, Eliza Clark

The Wren, The Wren, Anne Enright

A House for Alice, Diana Evans

Piglet, Lottie Hazell

Pineapple Street, Jenny Jackson

Yellowface, R. F. Kuang

Biography of X, Catherine Lacey

Julia, Sandra Newman

The Vulnerables, Sigrid Nunez

Tom Lake, Ann Patchett

In Memory of Us, Jacqueline Roy

The Fraud, Zadie Smith

Land of Milk and Honey, C. Pam Zhang

Wish List

Family Lore, Elizabeth Acevedo

The Sleep Watcher, Rowan Hisayo Buchanan

The Unfortunates, J. K. Chukwu

The Three Graces, Amanda Craig

Learned by Heart, Emma Donoghue

Service, Sarah Gilmartin

The Vaster Wilds, Lauren Groff

Reproduction, Louisa Hall

Happiness Falls, Angie Kim

Bright Young Women, Jessica Knoll

A Sign of Her Own, Sarah Marsh

The Fetishist, Katherine Min

Hello Beautiful, Ann Napolitano

Mrs S, K Patrick

Romantic Comedy, Curtis Sittenfeld

Absolutely and Forever, Rose Tremain

If I’m lucky, I’ll get a few right from across these two lists; no doubt I’ll be kicking myself over the ones I considered but didn’t include, and marvelling at the ones I’ve never heard of…

What would you like to see on the longlist?

Appendix

(A further 50 novels that were on my radar but didn’t make the cut. Like last year, I made things easy for myself by keeping an ongoing list of eligible novels in a file on my desktop.)

Everything Is Not Enough, Lola Akinmade Akerstrom

The Wind Knows My Name, Isabel Allende

Swanna in Love, Jennifer Belle

The Sisterhood, Katherine Bradley

The Fox Wife, Yangsze Choo

The Guest, Emma Cline

Speak to Me, Paula Cocozza

Talking at Night, Claire Daverley

Clear, Carys Davies

Bellies, Nicola Dinan

The Happy Couple, Naoise Dolan

In Such Tremendous Heat, Kehinde Fadipe

The Memory of Animals, Claire Fuller

Anita de Monte Laughs Last, Xochitl Gonzalez

Normal Women, Ainslie Hogarth

Sunburn, Chloe Michelle Howarth

Loot, Tania James

The Half Moon, Mary Beth Keane

Morgan Is My Name, Sophie Keetch

Soldier Sailor, Claire Kilroy

8 Lives of a Century-Old Trickster, Mirinae Lee

August Blue, Deborah Levy

Winter Animals, Ashani Lewis

Rosewater, Liv Little

The Couples, Lauren Mackenzie

Tell Me What I Am, Una Mannion

She’s a Killer, Kirsten McDougall

The Misadventures of Margaret Finch, Claire McGlasson

Nightbloom, Peace Adzo Medie

I Am Homeless If This Is Not My Home, Lorrie Moore

The Lost Wife, Susanna Moore

Okay Days, Jenny Mustard

Parasol against the Axe, Helen Oyeyemi

The Human Origins of Beatrice Porter and Other Essential Ghosts, Soraya Palmer

The Lodgers, Holly Pester

Night Wherever We Go, Tracey Rose Peyton

The Mars House, Natasha Pulley

Playing Games, Huma Qureshi

Come and Get It, Kiley Reid

High Time, Hannah Rothschild

Commitment, Mona Simpson

Death of a Bookseller, Alice Slater

Bird Life, Anna Smail

Stealing, Margaret Verble

Help Wanted, Adelle Waldman

Temper, Phoebe Walker

Hang the Moon, Jeannette Walls

Moral Injuries, Christie Watson

Ghost Girl, Banana, Wiz Wharton

Speak of the Devil, Rose Wilding

Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award shadow panel

I’m delighted to announce that I’ve been invited to be on the official shadow panel for the Sunday Times / Peters Fraser + Dunlop Young Writer of the Year Award, in association with The University of Warwick (to give it its full and proper title). Here’s a bit of background on the prize, from its website:

The prize “is awarded annually to the best work of published or self-published fiction, non-fiction or poetry by a British or Irish author aged between 18 and 35, and has gained attention and acclaim across the publishing industry and press. £5,000 is given to the overall winner and £500 to each of the three runners-up.

“Since it began in 1991, the award has had a striking impact, boasting a stellar list of alumni that have gone on to become leading lights of contemporary literature. The 2016 Award was presented to Max Porter for his extraordinary debut, Grief Is the Thing with Feathers. Following a five-year break, the prestigious award returned with a bang in 2015, awarding debut poet Sarah Howe the top prize for her phenomenal first collection, Loop of Jade.”

Past winners include Ross Raisin, Adam Foulds, Naomi Alderman, Robert Macfarlane, William Fiennes, Zadie Smith, Sarah Waters, Francis Spufford, Simon Armitage and Helen Simpson.

This year’s official judging panel is made up of Andrew Holgate, literary editor of the Sunday Times, and writers Lucy Hughes-Hallett and Elif Shafak.

I’m joined on the shadow panel by four other book bloggers, several of whom you will recognize as long-time friends of this blog:

- Dane Cobain (SocialBookshelves)

- Eleanor Franzen (Elle Thinks)

- Annabel Gaskell (Annabookbel)

- Clare Rowland (A Little Blog of Books)

Here are some key upcoming dates:

- Sunday October 29th: shortlist announced in Sunday Times

- November 18th: book bloggers event with readings from the shortlisted authors (Groucho Club, London)

- November 27th: deadline for shadow panel winner decision

- November 29th: shadow panel winner announced on STPFD website

- December 3rd: shadow panel winner announced in Sunday Times

- December 7th: prize-giving ceremony and winner announcement (London Library)

I’m so looking forward to getting stuck into the shortlisted books and discussing them! I’ll be posting a review of each one in November.

Library Checkout: July 2017

I’m flying out to America later today on a short trip for my sister’s wedding, so I’ve been focusing on finishing most of the books I have out from the library, including some that have hung around for a number of months already. I’ll have just one or two awaiting me on my return.

(Ratings and links to any books that I haven’t already featured here in some way or don’t plan to soon.)

LIBRARY BOOKS READ

- Hidden Nature: A Voyage of Discovery by Alys Fowler

- Bee Quest: In Search of Rare Bees by Dave Goulson

- A Horse Walks into a Bar by David Grossman

- Signs for Lost Children by Sarah Moss

LIBRARY BOOKS SKIMMED

- The Power by Naomi Alderman

CURRENTLY READING

- The Argonauts by Maggie Nelson – I’ll either take this with me or put it on hold until I come back; I haven’t decided as of the time of scheduling this post. In any case, it’s the sort of fragmentary narrative that doesn’t have to be read all at once.

CHECKED OUT, TO BE READ

- White Tears by Hari Kunzru

RETURNED UNFINISHED

- Human Acts by Han Kang – I read the first 115 pages and then set this aside, not because it was too harrowing or challenging, but simply because I’d been bored for at least 45 pages and didn’t have the patience to see how the various chapters, each from a different perspective (2nd person, then 1st, then 3rd) might fit together.

RETURNED UNREAD

- Tiny Giants by Nate Powell – I glanced at the first few pages of this graphic novel but didn’t like the drawing style or the narration.

(Hosted by Charleen of It’s a Portable Magic.)

Have you been taking advantage of your local libraries? What appeals from my lists?

Catching Up on Prize Winners: Alderman, Grossman & Whitehead

Sometimes I love a prize winner and cheer the judges’ ruling; other times I shake my head and puzzle over how they could possibly think this was the best the year had to offer. I’m late to the party for these three recent prize-winning novels. I’m also a party pooper, I guess, because I didn’t particularly like or dislike a one of them. (Reviews are in the order in which I read the books. My rating for all three =  )

)

A Horse Walks into a Bar by David Grossman

(Winner of the Man Booker International Prize)

“Why the long face? Did someone die? It’s only stand-up comedy!” Except that for the comedian himself, Dovaleh Greenstein, this swan song of a show in the Israeli town of Netanya devolves into the story of the most traumatic day of his life. Grossman has made what seems to me an unusual choice of narrator: Avishai Lazar, a widower and Supreme Court justice, and Dov’s acquaintance from adolescence – they were in the same military training camp. Dov has invited him here to bear witness, and by the end we know Avishai will produce a written account of the evening.

“Why the long face? Did someone die? It’s only stand-up comedy!” Except that for the comedian himself, Dovaleh Greenstein, this swan song of a show in the Israeli town of Netanya devolves into the story of the most traumatic day of his life. Grossman has made what seems to me an unusual choice of narrator: Avishai Lazar, a widower and Supreme Court justice, and Dov’s acquaintance from adolescence – they were in the same military training camp. Dov has invited him here to bear witness, and by the end we know Avishai will produce a written account of the evening.

Although it could be said that Avishai’s asides about the past, and about the increasingly restive crowd in the club, give us a rest from Dov’s claustrophobic monologue, in doing so they break the spell. This would be more hard-hitting as a play or a short story composed entirely of speech; in one of those formats, Dov’s story might keep you spellbound through a single sitting. Instead, I found that I had to force myself to read even five or 10 pages at a time. There’s no doubt Grossman can weave a clever tale about loss, and there are actually some quite funny jokes in here too, but overall I found this significantly less powerful than the author’s previous work, Falling Out of Time.

The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead

(Winner of the Pulitzer Prize, National Book Award and Arthur C. Clarke Award; longlisted for the Man Booker Prize)

Following Cora on her fraught journey from her Georgia plantation through the Carolinas and Tennessee to Indiana is enjoyable enough, with the requisite atrocities like lynchings and rapes thrown in to make sure it’s not just a picaresque cat-and-mouse battle between her and Arnold Ridgeway, the villainous slavecatcher. But I’m surprised that such a case has been made for the uniqueness of this novel based on a simple tweak of the historical record: Whitehead imagines the Underground Railroad as an actual subterranean transport system. This makes less of a difference than you might expect; if anything, it renders the danger Cora faces more abstract. The same might be said for the anachronistic combination of enlightened and harsh societies she passes through: by telescoping out to show the range of threats African-Americans faced between the Civil War and the 1930s, the novel loses immediacy.

Following Cora on her fraught journey from her Georgia plantation through the Carolinas and Tennessee to Indiana is enjoyable enough, with the requisite atrocities like lynchings and rapes thrown in to make sure it’s not just a picaresque cat-and-mouse battle between her and Arnold Ridgeway, the villainous slavecatcher. But I’m surprised that such a case has been made for the uniqueness of this novel based on a simple tweak of the historical record: Whitehead imagines the Underground Railroad as an actual subterranean transport system. This makes less of a difference than you might expect; if anything, it renders the danger Cora faces more abstract. The same might be said for the anachronistic combination of enlightened and harsh societies she passes through: by telescoping out to show the range of threats African-Americans faced between the Civil War and the 1930s, the novel loses immediacy.

Ultimately, I felt little attachment to Cora and had to force myself to keep plodding through her story. My favorite parts were little asides giving other characters’ backstories. There’s no doubt Whitehead can shape a plot and dot in apt metaphors (I particularly liked “Ajarry died in the cotton, the bolls bobbing around her like whitecaps on the brute ocean”). However, I kept thinking, Haven’t I read this story before? (Beloved, Ruby, The Diary of Anne Frank; seen on screen in Twelve Years a Slave, Roots and the like.) This is certainly capably written, but doesn’t stand out for me compared to Homegoing, which was altogether more affecting.

The Power by Naomi Alderman

(Winner of the [Bailey’s] Women’s Prize)

I read the first ~120 pages and skimmed the rest. Alderman imagines a parallel world in which young women realize they wield electrostatic power that can maim or kill. In an Arab Spring-type movement, they start to take back power from their oppressive societies. You’ll cheer as women caught up in sex trafficking fight back and take over. The movement is led by Allie, an abused child who starts by getting revenge on her foster father and then takes her message worldwide, becoming known as Mother Eve.

I read the first ~120 pages and skimmed the rest. Alderman imagines a parallel world in which young women realize they wield electrostatic power that can maim or kill. In an Arab Spring-type movement, they start to take back power from their oppressive societies. You’ll cheer as women caught up in sex trafficking fight back and take over. The movement is led by Allie, an abused child who starts by getting revenge on her foster father and then takes her message worldwide, becoming known as Mother Eve.

Alderman has cleverly set this up as an anthropological treatise-cum-historical novel authored by “Neil Adam Armon” (an anagram of her own name), complete with documents and drawings of artifacts. “The power to hurt is a kind of wealth,” and in this situation of gender reversal women gradually turn despotic. They are soldiers and dictators; they inflict genital mutilation and rape on men.

I enjoyed the passages mimicking the Bible, but felt a lack of connection with the characters and didn’t get a sense of years passing even though this is spread over about a decade. This is most like Margaret Atwood’s MaddAddam trilogy – Alderman’s debt to Atwood is explicit, in the dedication as well as the acknowledgments – so if you really like those books, by all means read this one. My usual response to such speculative fiction, though, even if it describes a believable situation, is: what’s the point? As with “Erewhon,” the best story in Helen Simpson’s collection Cockfosters, the points about gender roles are fairly obvious.

I’d be interested to hear if you’ve read any of these books – or plan to read them – and believe they were worthy prize winners. If so, set me straight!

Making Plans (and Book Lists) for America

On Tuesday we leave for two weeks in America. It’s nearly a year and a half since our last trip – much too long – so we’ll be cramming in lots of visits with friends and family and doing a fair bit of driving around the Mid-Atlantic states. I’m giving myself the whole time off, which means I’ve been working flat out for the past two weeks to get everything done (including my U.K. and U.S. taxes). I’m nearly there: at the 11-day countdown I still had 12 books I wanted to finish and 12 reviews to write; now I’m down to five books, only one of which might be considered essential, and all the reviews are ready to submit/schedule. What with the holiday weekend underway, it should all be manageable.

I’m a compulsive list maker in general, but especially when it comes to preparing for a trip. I’ve kept adding to lists entitled “Pack for America,” “Do in America,” “Buy in America,” and “Bring back from America.” But the more fun lists to make are book-related ones: what paper books should I take to read on the plane? Which of the 315 books on my Kindle ought I to prioritize over the next two weeks? Which exclusively American books should I borrow from the public library? What secondhand books will I try to find? And which of the books in the dozens of boxes in the closet of my old bedroom will I fit in my suitcase for the trip back?

I liked the sound of Laila’s habit of taking an Anne Tyler novel on every flight. That’s just the kind of cozy reading I want, especially as I head back to Maryland – not far at all from Tyler’s home turf of Baltimore. I browsed the blurbs on a few of her paperbacks I have lying around and chose Back When We Were Grownups to be my fifth Tyler and one of my airplane reads.

I’m also tempted by Min Kym’s Gone, a memoir by a violin virtuoso about having her Stradivarius stolen. I picked up a proof copy in a 3-for-£1 charity sale a couple of weeks ago. And then I can’t resist the aptness of Jonathan Miles’s Dear American Airlines (even though we’re actually flying on Virgin). I’ll start one or more of these before we go, just to make sure they ‘take’.

I almost certainly won’t need three print books for the trip, particularly if I take advantage of the in-flight entertainment. We only ever seem to watch films while we’re in America or en route there, so between the two legs I’ll at least try to get to La La Land and The Light between Oceans; I’m also considering Nocturnal Animals, Silence, and the live-action Beauty and the Beast – anyone seen these?

However, I’ll also keep my Kindle to hand, as I find it easier to pick up and put down on multi-part journeys like ours to the airport (train ride + coach ride). Some of the books on my Kindle priority list are: The Day that Went Missing by Richard Beard, Cork Dork by Bianca Bosker, Eleanor Oliphant Is Completely Fine by Gail Honeyman, The Fact of a Body by Alexandria Marzano-Lesnevich, Mrs. Fletcher by Tom Perrotta (out in August), The Power by Naomi Alderman, Reservoir 13 by Jon McGregor, The Rules Do Not Apply by Ariel Levy, See What I have Done by Sarah Schmidt, You Should Have Left by Daniel Kehlmann … and the list continues, but I’ll stop there.

My book shopping list is an ongoing one, as the many cross-outs and additions on this sheet show. Finding specific books at my beloved Wonder Book can be a challenge, so I usually just keep in mind the names of authors I’d like to read more by. This time that might include Arnold Bennett, Geoff Dyer, Elizabeth Hay, Bernd Heinrich, W. Somerset Maugham, Haruki Murakami and Kathleen Norris. In addition to the couple of secondhand bookstores we always hit, I hope to visit a few new-to-me ones on stays with friends in Virginia.

As for those poor books sat in boxes in the closet, I have plans to unearth novels by Anita Brookner, Mohsin Hamid, Kent Haruf, Penelope Lively, Howard Norman and Philip Roth – for reading while I’m there and/or bringing back with me. I’m also contemplating borrowing my dad’s omnibus edition of the John Updike “Rabbit” novels. From my nonfiction hoard, I fancy an Alexandra Fuller memoir, D.H. Lawrence’s travel books and more of May Sarton’s journals. If only it weren’t for luggage weight limits!

On Monday I’ll publish my intercontinental Library Checkout, on Tuesday I have a few June releases to recommend, and then I’m scheduling a handful of posts for while I’m away – a couple reviews I happen to have ready, plus some other lightweight stuff. Alas, I read no doorstoppers in May, but I have a list (of course) of potential ones for June, so will attempt to resurrect that monthly column.

Though I may be slow to respond to comments and read your blogs while I’m away, I will do my best and hope to catch up soon after I’m back.

2016 Runners-Up and Other Superlatives

Let’s hear it for the ladies! In 2016 women writers accounted for 9 out of my 15 top fiction picks, 12 out of my 15 nonfiction selections, and 8 of the 10 runners-up below. That’s 73%. The choices below are in alphabetical order by author, with any full reviews linked in. Many of these have already appeared on the blog in some form over the course of the year.

Ten Runners-Up:

FICTION

Hag-Seed by Margaret Atwood: Atwood looks more like a good witch every year, and here she works her magic on The Tempest to produce the most satisfying volume of the Hogarth Shakespeare series yet. There’s a really clever play-within-the-play-within-the-play thing going on, and themes of imprisonment and performance resonate in multiple ways.

Hag-Seed by Margaret Atwood: Atwood looks more like a good witch every year, and here she works her magic on The Tempest to produce the most satisfying volume of the Hogarth Shakespeare series yet. There’s a really clever play-within-the-play-within-the-play thing going on, and themes of imprisonment and performance resonate in multiple ways.

The Atomic Weight of Love by Elizabeth J. Church: In Church’s debut, an amateur ornithologist learns about love and sacrifice through marriage to a Los Alamos physicist and a relationship with a Vietnam veteran. I instantly warmed to Meri as a narrator and loved following her unpredictable life story.

The Atomic Weight of Love by Elizabeth J. Church: In Church’s debut, an amateur ornithologist learns about love and sacrifice through marriage to a Los Alamos physicist and a relationship with a Vietnam veteran. I instantly warmed to Meri as a narrator and loved following her unpredictable life story.

We Love You, Charlie Freeman by Kaitlyn Greenidge: The Freemans are raising Charlie, a chimpanzee, as part of their family for a Toneybee Institute experiment and teaching him to communicate via sign language. This is a rich and unsettling story of human–human interactions, even more so than human–animal interactions; it’s a great first novel and I will follow Greenidge’s career with interest.

We Love You, Charlie Freeman by Kaitlyn Greenidge: The Freemans are raising Charlie, a chimpanzee, as part of their family for a Toneybee Institute experiment and teaching him to communicate via sign language. This is a rich and unsettling story of human–human interactions, even more so than human–animal interactions; it’s a great first novel and I will follow Greenidge’s career with interest.

To the Bright Edge of the World by Eowyn Ivey: Ivey’s intricate second novel weaves together diaries, letters, photographs, and various other documents and artifacts to tell the gently supernatural story of an exploratory mission along Alaska’s Wolverine River in 1885 and its effects through to the present day. I can highly recommend this rollicking adventure tale to fans of historical fiction and magic realism.

by Eowyn Ivey: Ivey’s intricate second novel weaves together diaries, letters, photographs, and various other documents and artifacts to tell the gently supernatural story of an exploratory mission along Alaska’s Wolverine River in 1885 and its effects through to the present day. I can highly recommend this rollicking adventure tale to fans of historical fiction and magic realism.

This Must Be the Place by Maggie O’Farrell: Spreading outward from Ireland and reaching into every character’s past and future, this has all O’Farrell’s trademark insight into family and romantic relationships, as well as her gorgeous prose and precise imagery. I have always felt that O’Farrell expertly straddles the (perhaps imaginary) line between literary and popular fiction; her books are addictively readable but also hold up to critical scrutiny.

by Maggie O’Farrell: Spreading outward from Ireland and reaching into every character’s past and future, this has all O’Farrell’s trademark insight into family and romantic relationships, as well as her gorgeous prose and precise imagery. I have always felt that O’Farrell expertly straddles the (perhaps imaginary) line between literary and popular fiction; her books are addictively readable but also hold up to critical scrutiny.

Commonwealth by Ann Patchett: This deep study of blended family dynamics starts with an early 1960s christening party Los Angeles policeman Fix Keating is throwing for his younger daughter, Franny; we see the aftermath of that party in the lives of six step-siblings in the decades to come. This is a sophisticated and atmospheric novel I would not hesitate to recommend to literary fiction fans in general and Patchett fans in particular.

by Ann Patchett: This deep study of blended family dynamics starts with an early 1960s christening party Los Angeles policeman Fix Keating is throwing for his younger daughter, Franny; we see the aftermath of that party in the lives of six step-siblings in the decades to come. This is a sophisticated and atmospheric novel I would not hesitate to recommend to literary fiction fans in general and Patchett fans in particular.

The Last Painting of Sara de Vos by Dominic Smith: Jessie Burton, Tracy Chevalier and all others who try to write historical fiction about the Netherlands in the seventeenth century, eat your hearts out. Such a beautiful epoch-spanning novel about art and regret.

The Last Painting of Sara de Vos by Dominic Smith: Jessie Burton, Tracy Chevalier and all others who try to write historical fiction about the Netherlands in the seventeenth century, eat your hearts out. Such a beautiful epoch-spanning novel about art and regret.

Shelter by Jung Yun: A Korean-American family faces up to violence past and present in a strong debut that offers the hope of redemption. I would recommend this to fans of David Vann and Richard Ford.

NONFICTION

I Will Find You by Joanna Connors: By using present-tense narration, Connors makes the events of 1984 feel as if they happened yesterday: a blow-by-blow of the sex acts forced on her at knife-point over the nearly one-hour duration of her rape; the police reports and trials; and the effects it all had on her marriage and family. This is an excellent work of reconstruction and investigative reporting.

by Joanna Connors: By using present-tense narration, Connors makes the events of 1984 feel as if they happened yesterday: a blow-by-blow of the sex acts forced on her at knife-point over the nearly one-hour duration of her rape; the police reports and trials; and the effects it all had on her marriage and family. This is an excellent work of reconstruction and investigative reporting.

Another Day in the Death of America by Gary Younge: Younge built this book by choosing a 24-hour period (November 22 to 23, 2013) and delving into all 10 gun deaths of young Americans on record for that time: seven black, two Latino, and one white; aged nine to 18; about half at least vaguely gang-related, while in two – perhaps the most crushing cases – there was an accident while playing around with a gun. I dare anyone to read this and then try to defend gun ‘rights’ in the face of such senseless, everyday loss.

Another Day in the Death of America by Gary Younge: Younge built this book by choosing a 24-hour period (November 22 to 23, 2013) and delving into all 10 gun deaths of young Americans on record for that time: seven black, two Latino, and one white; aged nine to 18; about half at least vaguely gang-related, while in two – perhaps the most crushing cases – there was an accident while playing around with a gun. I dare anyone to read this and then try to defend gun ‘rights’ in the face of such senseless, everyday loss.

Various Superlatives:

Best Discoveries of the Year: Apollo Classics reprints (I reviewed three of them this year); Diana Abu-Jaber, Linda Grant and Kristopher Jansma.

Most Pleasant Year-Long Reading Experience: The seasonal anthologies issued by the UK Wildlife Trusts and edited by Melissa Harrison (I reviewed three of them this year).

Most Improved: I heartily disliked Sarah Perry’s debut novel, After Me Comes the Flood. But her second, The Essex Serpent, is exquisite.

Debut Novelists Whose Next Work I’m Most Looking Forward to: Stephanie Danler, Kaitlyn Greenidge, Francis Spufford, Andria Williams and Sunil Yapa.

The Year’s Biggest Disappointments: Here I Am by Jonathan Safran Foer, Today Will Be Different by Maria Semple, and Swing Time by Zadie Smith. Here’s hoping 2017 doesn’t bring any letdowns from beloved authors.

The Worst Book I Read This Year: Paulina & Fran (2015) by Rachel B. Glaser. My only one-star review of the year. ’Nuff said?

The 2016 Novels I Most Wish I’d Gotten to: (At least the 10 I’m most regretful about)

- The Power by Naomi Alderman

- The Museum of You by Carys Bray

- The Course of Love by Alain de Botton

- What Belongs to You by Garth Greenwell*

Homegoing by Yaa Gyasi

Homegoing by Yaa Gyasi- The Waiting Room by Leah Kaminsky

- The Inseparables by Stuart Nadler

- Harmony by Carolyn Parkhurst*

- The Nest by Cynthia D’Aprix Sweeney*

- The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead*

*Haven’t been able to find anywhere yet; the rest are on my Kindle.

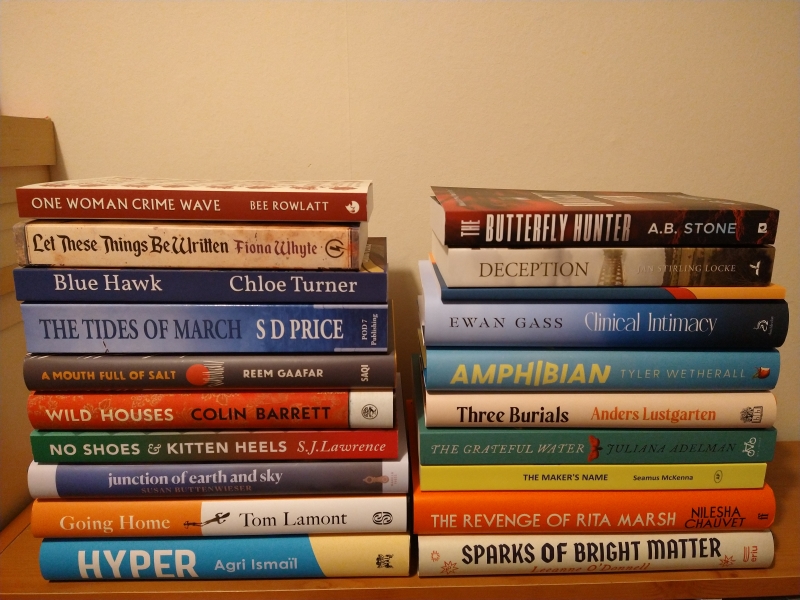

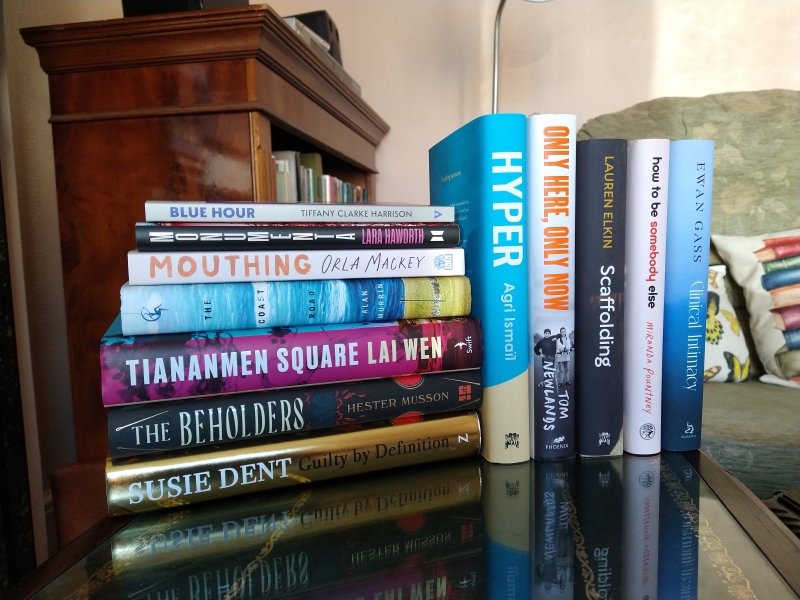

Etymology and Shakespeare studies are the keys to solving a cold case in Susie Dent’s clever, engrossing mystery, Guilty by Definition.

Etymology and Shakespeare studies are the keys to solving a cold case in Susie Dent’s clever, engrossing mystery, Guilty by Definition. Psychoanalysis, motherhood, and violence against women are resounding themes in Lauren Elkin’s Scaffolding. As history repeats itself one sweltering Paris summer, the personal and political structures undergirding the protagonists’ parallel lives come into question. This fearless, sophisticated work ponders what to salvage from the past—and what to tear down.

Psychoanalysis, motherhood, and violence against women are resounding themes in Lauren Elkin’s Scaffolding. As history repeats itself one sweltering Paris summer, the personal and political structures undergirding the protagonists’ parallel lives come into question. This fearless, sophisticated work ponders what to salvage from the past—and what to tear down. Clinical Intimacy’s mysterious antihero comes to life through interviews with his family, friends and clients. The brilliant oral history format builds a picture of isolation among vulnerable populations, only alleviated by care and touch—especially during Covid-19. Ewan Gass’s intricate story reminds us of the ultimate unknowability of other people.

Clinical Intimacy’s mysterious antihero comes to life through interviews with his family, friends and clients. The brilliant oral history format builds a picture of isolation among vulnerable populations, only alleviated by care and touch—especially during Covid-19. Ewan Gass’s intricate story reminds us of the ultimate unknowability of other people.

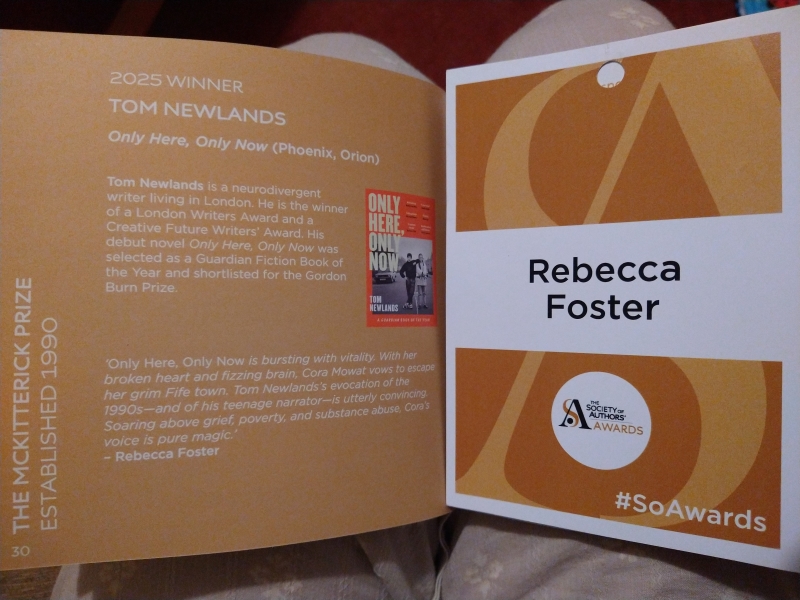

Only Here, Only Now is bursting with vitality. With her broken heart and fizzing brain, Cora Mowat vows to escape her grim Fife town. Tom Newlands’s evocation of the 1990s—and of his teenage narrator—is utterly convincing. Soaring above grief, poverty, and substance abuse, Cora’s voice is pure magic.

Only Here, Only Now is bursting with vitality. With her broken heart and fizzing brain, Cora Mowat vows to escape her grim Fife town. Tom Newlands’s evocation of the 1990s—and of his teenage narrator—is utterly convincing. Soaring above grief, poverty, and substance abuse, Cora’s voice is pure magic.

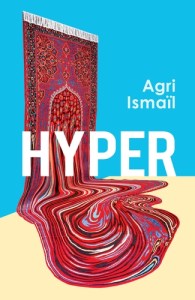

Hyper by Agri Ismaïl [I longlisted it – and then shortlisted it – but was outvoted]

Hyper by Agri Ismaïl [I longlisted it – and then shortlisted it – but was outvoted] How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney [It had two votes to make the shortlist, but because it was so similar to Scaffolding in its basics (a thirtysomething woman in a big city, the question of motherhood, and pregnancy loss) we decided to cut it.]

How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney [It had two votes to make the shortlist, but because it was so similar to Scaffolding in its basics (a thirtysomething woman in a big city, the question of motherhood, and pregnancy loss) we decided to cut it.]

Naomi Alderman, musing on the intestines, draws metaphorical connections between food, sex and death, and gives thanks that digestion and excretion are involuntary processes we don’t have to give any thought. Ned Beauman reports on misconceptions about the appendix as he frets about the odds of his bursting while he’s in America without health insurance. The late Philip Kerr describes the checkered history of the lobotomy, which used to reduce patients to a vegetative state but can now quite effectively treat epilepsy.

Naomi Alderman, musing on the intestines, draws metaphorical connections between food, sex and death, and gives thanks that digestion and excretion are involuntary processes we don’t have to give any thought. Ned Beauman reports on misconceptions about the appendix as he frets about the odds of his bursting while he’s in America without health insurance. The late Philip Kerr describes the checkered history of the lobotomy, which used to reduce patients to a vegetative state but can now quite effectively treat epilepsy. Most authors chose a particular organ because of its importance to their own health. Christina Patterson’s acne was so bad she went to the UK’s top skin specialist for PUVA light treatments, Mark Ravenhill had his gallbladder removed in an emergency surgery, and Daljit Nagra’s asthma led his parents to engage Sikh faith healers for his lungs. Two of my favorite chapters were by William Fiennes, whose extreme Crohn’s disease caused him to have a colostomy bag for two years in his early twenties, and poet Kayo Chingonyi, who has always been ashamed to admit that his parents both died of complications of HIV in Zambia. Such personal connections add poignancy to what could have been information dumps.

Most authors chose a particular organ because of its importance to their own health. Christina Patterson’s acne was so bad she went to the UK’s top skin specialist for PUVA light treatments, Mark Ravenhill had his gallbladder removed in an emergency surgery, and Daljit Nagra’s asthma led his parents to engage Sikh faith healers for his lungs. Two of my favorite chapters were by William Fiennes, whose extreme Crohn’s disease caused him to have a colostomy bag for two years in his early twenties, and poet Kayo Chingonyi, who has always been ashamed to admit that his parents both died of complications of HIV in Zambia. Such personal connections add poignancy to what could have been information dumps. During the weeks that I spent with these essays I was frequently reminded of Jan Morris’s

During the weeks that I spent with these essays I was frequently reminded of Jan Morris’s

As he ushers readers around the world, Szalay invites us to marvel at how quickly life changes and how – improbable as it may seem – we can have a real impact on people we may only meet once. There’s a strong contrast between impersonal and intimate spaces: airplane cabins and hotel rooms versus the private places where relationships start or end. The title applies to the characters’ tumultuous lives as much as to the flight conditions. They experience illness, infidelity, domestic violence, homophobia and more, but they don’t stay mired in their situations; there’s always a sense of motion and possibility, that things will change one way or another.

As he ushers readers around the world, Szalay invites us to marvel at how quickly life changes and how – improbable as it may seem – we can have a real impact on people we may only meet once. There’s a strong contrast between impersonal and intimate spaces: airplane cabins and hotel rooms versus the private places where relationships start or end. The title applies to the characters’ tumultuous lives as much as to the flight conditions. They experience illness, infidelity, domestic violence, homophobia and more, but they don’t stay mired in their situations; there’s always a sense of motion and possibility, that things will change one way or another. Human Acts, Han Kang: I admit, this book, which traces the human costs of the brutally repressed Gwanju Uprising, is difficult to read. Worth the effort, though, for its urgent questions about the nature of humanity.

Human Acts, Han Kang: I admit, this book, which traces the human costs of the brutally repressed Gwanju Uprising, is difficult to read. Worth the effort, though, for its urgent questions about the nature of humanity. Pachinko, Min Jin Lee: A twentieth-century family saga about Korean immigrants in Japan. Expansive and richly textured.

Pachinko, Min Jin Lee: A twentieth-century family saga about Korean immigrants in Japan. Expansive and richly textured. The Essex Serpent, Sarah Perry: A recently widowed natural historian and a village curate spar over rumors of a returned prehistoric serpent. Sumptuous.

The Essex Serpent, Sarah Perry: A recently widowed natural historian and a village curate spar over rumors of a returned prehistoric serpent. Sumptuous. Lincoln in the Bardo, George Saunders: The resident ghosts look on with consternation as Abraham Lincoln visits their cemetery to mourn over the body of his son, Willie. Polyphonic; extraordinarily moving.

Lincoln in the Bardo, George Saunders: The resident ghosts look on with consternation as Abraham Lincoln visits their cemetery to mourn over the body of his son, Willie. Polyphonic; extraordinarily moving. The Wanderers, Meg Howrey: Three astronauts undertake a long-term simulation of a mission to Mars, leaving their loved ones behind. Wonderful literary sci-fi, absorbing in its physical and psychological detail.

The Wanderers, Meg Howrey: Three astronauts undertake a long-term simulation of a mission to Mars, leaving their loved ones behind. Wonderful literary sci-fi, absorbing in its physical and psychological detail. Exit West, Mohsin Hamid: Two young lovers become part of a global migration through mysterious doors that connect locations all over the world. Intimate and tender.

Exit West, Mohsin Hamid: Two young lovers become part of a global migration through mysterious doors that connect locations all over the world. Intimate and tender. My Darling Detective, Howard Norman: A tale of family secrets set in 1970s Halifax, featuring plainspoken people and delightful use of radio drama. From my review: “noir with a spring in its step and a lilt in its voice.”

My Darling Detective, Howard Norman: A tale of family secrets set in 1970s Halifax, featuring plainspoken people and delightful use of radio drama. From my review: “noir with a spring in its step and a lilt in its voice.” Days Without End, Sebastian Barry: Irish immigrant Thomas McNulty chronicles his survival in the American West (and the Civil War) and his love for fellow soldier John Cole. Fearsomely beautiful.

Days Without End, Sebastian Barry: Irish immigrant Thomas McNulty chronicles his survival in the American West (and the Civil War) and his love for fellow soldier John Cole. Fearsomely beautiful. The Mountain, Paul Yoon: Six exquisite short stories, set in different locations over the past 100 years, from a master of the form.

The Mountain, Paul Yoon: Six exquisite short stories, set in different locations over the past 100 years, from a master of the form. The Stone Sky, N. K. Jemisin: The blistering final book in Ms. Jemisin’s stunning Broken Earth trilogy (must be read in order, so start with The Fifth Season if you’re new to the series). Superb speculative fiction.

The Stone Sky, N. K. Jemisin: The blistering final book in Ms. Jemisin’s stunning Broken Earth trilogy (must be read in order, so start with The Fifth Season if you’re new to the series). Superb speculative fiction. Little Fires Everywhere, Celeste Ng: The complexities of race, class, and motherhood swirl in a Cleveland suburb (my hometown) in this deft, compassionate novel.

Little Fires Everywhere, Celeste Ng: The complexities of race, class, and motherhood swirl in a Cleveland suburb (my hometown) in this deft, compassionate novel. Her Body and Other Parties, Carmen Maria Machado: Short stories grounded in the body but shot through with elements of horror and fantasy. Won’t take it easy on you, but you won’t want to stop reading, either. Brilliant.

Her Body and Other Parties, Carmen Maria Machado: Short stories grounded in the body but shot through with elements of horror and fantasy. Won’t take it easy on you, but you won’t want to stop reading, either. Brilliant. The Power, Naomi Alderman: Women harness a power within themselves that turns the tables on men. Atwoodian dystopia at its finest.

The Power, Naomi Alderman: Women harness a power within themselves that turns the tables on men. Atwoodian dystopia at its finest.