Women’s Prize 2024: Longlist Predictions vs. Wishes

This is the fourth year in a row that I’ve made predictions for the Women’s Prize longlist (the real thing comes out on Tuesday, 6 p.m. GMT). It shows how invested I’ve become in this prize in recent years. Like I did last year, I’ll give predictions, then wishes (no overlap this time!). My wishes are based on what I have already read and want to read. Although I kept tabs on publishers and ‘free entries’ for previous winners and shortlistees, I didn’t let quotas determine my selections. And while I kept in mind that there are two novelists on the judging panel, I don’t know enough about any of these judges’ taste to be able to tailor my predictions. My only thought was that they will probably appreciate good old-fashioned storytelling … but also innovative storytelling.

(There are two books – The List of Suspicious Things by Jennie Godfrey (= Joanna Cannon?) and Jaded by Ela Lee (this year’s Queenie) – that I only heard about as I was preparing this post and seem pretty likely, but I felt that it would be cheating for me to include them.)

Predictions

The Three of Us, Ore Agbaje-Williams

The Future, Naomi Alderman

The Storm We Made, Vanessa Chan

Penance, Eliza Clark

The Wren, The Wren, Anne Enright

A House for Alice, Diana Evans

Piglet, Lottie Hazell

Pineapple Street, Jenny Jackson

Yellowface, R. F. Kuang

Biography of X, Catherine Lacey

Julia, Sandra Newman

The Vulnerables, Sigrid Nunez

Tom Lake, Ann Patchett

In Memory of Us, Jacqueline Roy

The Fraud, Zadie Smith

Land of Milk and Honey, C. Pam Zhang

Wish List

Family Lore, Elizabeth Acevedo

The Sleep Watcher, Rowan Hisayo Buchanan

The Unfortunates, J. K. Chukwu

The Three Graces, Amanda Craig

Learned by Heart, Emma Donoghue

Service, Sarah Gilmartin

The Vaster Wilds, Lauren Groff

Reproduction, Louisa Hall

Happiness Falls, Angie Kim

Bright Young Women, Jessica Knoll

A Sign of Her Own, Sarah Marsh

The Fetishist, Katherine Min

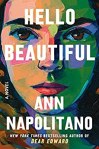

Hello Beautiful, Ann Napolitano

Mrs S, K Patrick

Romantic Comedy, Curtis Sittenfeld

Absolutely and Forever, Rose Tremain

If I’m lucky, I’ll get a few right from across these two lists; no doubt I’ll be kicking myself over the ones I considered but didn’t include, and marvelling at the ones I’ve never heard of…

What would you like to see on the longlist?

Appendix

(A further 50 novels that were on my radar but didn’t make the cut. Like last year, I made things easy for myself by keeping an ongoing list of eligible novels in a file on my desktop.)

Everything Is Not Enough, Lola Akinmade Akerstrom

The Wind Knows My Name, Isabel Allende

Swanna in Love, Jennifer Belle

The Sisterhood, Katherine Bradley

The Fox Wife, Yangsze Choo

The Guest, Emma Cline

Speak to Me, Paula Cocozza

Talking at Night, Claire Daverley

Clear, Carys Davies

Bellies, Nicola Dinan

The Happy Couple, Naoise Dolan

In Such Tremendous Heat, Kehinde Fadipe

The Memory of Animals, Claire Fuller

Anita de Monte Laughs Last, Xochitl Gonzalez

Normal Women, Ainslie Hogarth

Sunburn, Chloe Michelle Howarth

Loot, Tania James

The Half Moon, Mary Beth Keane

Morgan Is My Name, Sophie Keetch

Soldier Sailor, Claire Kilroy

8 Lives of a Century-Old Trickster, Mirinae Lee

August Blue, Deborah Levy

Winter Animals, Ashani Lewis

Rosewater, Liv Little

The Couples, Lauren Mackenzie

Tell Me What I Am, Una Mannion

She’s a Killer, Kirsten McDougall

The Misadventures of Margaret Finch, Claire McGlasson

Nightbloom, Peace Adzo Medie

I Am Homeless If This Is Not My Home, Lorrie Moore

The Lost Wife, Susanna Moore

Okay Days, Jenny Mustard

Parasol against the Axe, Helen Oyeyemi

The Human Origins of Beatrice Porter and Other Essential Ghosts, Soraya Palmer

The Lodgers, Holly Pester

Night Wherever We Go, Tracey Rose Peyton

The Mars House, Natasha Pulley

Playing Games, Huma Qureshi

Come and Get It, Kiley Reid

High Time, Hannah Rothschild

Commitment, Mona Simpson

Death of a Bookseller, Alice Slater

Bird Life, Anna Smail

Stealing, Margaret Verble

Help Wanted, Adelle Waldman

Temper, Phoebe Walker

Hang the Moon, Jeannette Walls

Moral Injuries, Christie Watson

Ghost Girl, Banana, Wiz Wharton

Speak of the Devil, Rose Wilding

Love Your Library & Miscellaneous News, July 2023

Thanks, as always, to Elle for her faithful participation (her post is here).

Today happens to be my 10th freelancing anniversary. I’m not much in the mood for celebrating as my career feels like it’s at a low ebb just now. However, I’m trying to be proactive: I contacted all my existing employers asking about the possibility of more work and a few opportunities are forthcoming. Plus I have a new paid review venue in the pipeline.

Tomorrow the Booker Prize longlist will be announced. I haven’t had a whole lot of time to think about it, but over the past few months I did keep a running list of novels I thought would be eligible, so here are 13 (a “Booker dozen”) that I think might be strong possibilities:

Old God’s Time, Sebastian Barry

The New Life, Tom Crewe

Fire Rush, Jacqueline Crooks

The Wren, The Wren, Anne Enright

The Vaster Wilds, Lauren Groff

Enter Ghost, Isabella Hammad

Hungry Ghosts, Kevin Jared Hosein

August Blue, Deborah Levy

The Sun Walks Down, Fiona McFarlane

Cuddy, Benjamin Myers

Shy, Max Porter

The Fraud, Zadie Smith

Land of Milk and Honey, C Pam Zhang

See also Clare’s and Susan’s predictions. All three of us coincide on one of these titles!

Back to the library content!

I appreciated this mini-speech by Bob Comet, the introverted librarian protagonist of Patrick deWitt’s The Librarianist, about why he loves libraries … but not people so much:

“I like the way I feel when I’m there. It’s a place that makes sense to me. I like that anyone can come in and get the books they want for free. The people bring the books home and take care of them, then bring them back so that other people can do the same. … I like the idea of people.”

I recently added a new regular task to my library volunteering roster: choosing a selection of the month’s new stock (30 fiction releases and 9 fiction) and adding them to a PDF template with the cover, title and author, and a blurb from the library catalogue or Goodreads, etc. The sheets are printed out at each branch library and displayed in a binder for patrons to browse. I was so proud to see my pages in there! There are three of us alternating this task, so I’ll be doing it four times a year. My next month is October.

On my Scotland travels last month, I took photos of two cute little libraries, one in Wigtown (L) and the other in Tarbert.

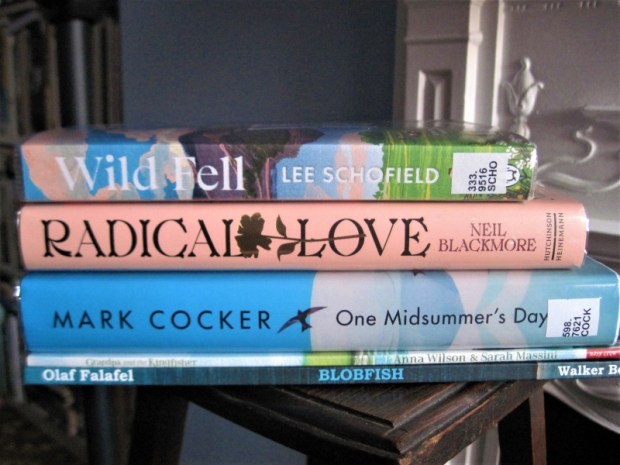

I’m currently on holiday again, with university friends in the Lake District for a week (Wild Fell, below, is for reading in advance of a trip to, and on location in, Haweswater), and you can be sure I brought plenty of library books along with me.

My reading and borrowing since last time:

READ

- The Happy Couple by Naoise Dolan

- Yellowface by Rebecca F. Kuang

- Death of a Bookseller by Alice Slater

- The Archaeology of Loss by Sarah Turlow

- The Legacy of Elizabeth Pringle by Kirsty Wark

- Sunburn by Andi Watson

- How Much of These Hills Is Gold by C. Pam Zhang (for book club)

+ 3 children’s picture books from the Wainwright Prize longlist:

- Blobfish by Olaf Falafel: Silly and with the merest scrape of an environmentalist message pasted on (the fish temporarily gets stuck in a plastic bag).

- The Zebra’s Great Escape by Katherine Rundell: Loved this super-cute, cheeky story of a little girl whose understanding of animal language allows her to become part of a natural network rescuing a menagerie held captive by an evil collector.

- Grandpa and the Kingfisher by Anna Wilson: Nice drawings and attention to nature and its seasonality, but rather mawkish. (Adult birds don’t die off annually!)

SKIMMED

- A Life of One’s Own: Nine Women Writers Begin Again by Joanna Biggs – The backstory is Biggs getting divorced in her thirties and moving to NYC. Her eight chosen female authors are VERY familiar, barring, perhaps, Zora Neale Hurston (thank goodness she chose two Black authors, as so many group biographies are all about white women). Do we need potted biographies of such well-known figures? Probably not. Nonetheless, it was clever how she wove her own story and reactions to their works into the biographical material, and the writing is so strong I could excuse any retreading of ground.

CURRENTLY READING

- One Midsummer’s Day by Mark Cocker

- King by Jonathan Eig

- Emily Wilde’s Encyclopaedia of Faeries by Heather Fawcett

- Milk by Alice Kinsella

- Wild Fell by Lee Schofield

CHECKED OUT, TO BE READ

Lots of lovely teal in this latest batch.

RETURNED UNFINISHED

- Undercurrent by Natasha Carthew – This was requested after me. I read 21% and will either pick it up on my Kindle via the NetGalley book or get it out another time.

- The Gifts by Liz Hyder – I’ll try this another time when I can give it more attention.

- Music in the Dark by Sally Magnusson – I loved The Ninth Child, but have DNFed her other two novels, alas! I even got to page 122 in this, but I had little interest in seeing how the storylines fit together.

- The Five Red Herrings by Dorothy L. Sayers – I’m awful about trying mystery series, usually DNFing or giving up after the first book. I just can’t care whodunnit.

What have you been reading or reviewing from the library recently?

Share a link to your own post in the comments. Feel free to use the above image. The hashtag is #LoveYourLibrary.

From the Dylan Thomas Prize Shortlist: Seven Steeples & I’m a Fan

The Swansea University International Dylan Thomas Prize recognizes the best published work in the English language written by an author aged 39 or under. All literary genres are eligible, so the shortlist contains a poetry collection as well as novels and short stories.

I’ve read half of the shortlist (also including Warsan Shire’s poems) and would be interested in trying the rest if I can source the two short story collections; Limberlost is at my library. The winner will be announced at 8 p.m. BST on Thursday 11 May.

Seven Steeples by Sara Baume

Isabel and Simon arrive one January at a shabby rental house in coastal Ireland overlooked by a mountain, in the middle of nowhere. They’d been menial workers in Dublin and met climbing a mountain, but somehow never seem to get around to climbing their new local peak. In moving here, these “two solitary misanthropes” are essentially rejecting society and kin; Baume describes them as “post-family.” It appears that they’re post-employment as well – there is never a single reference to how they pay the rent and buy the hipster foods they favour. Could young people’s savings really fund eight years’ rural living?

It’s an appealingly anti-consumerist vision, anyway: They arrive with one van-load of stuff and their adopted dogs, Pip and Voss, and otherwise make do with a haphazard collection of secondhand belongings left by previous tenants or donated by their estranged families. The house starts to fall apart around them, but for the most part they adjust to the decay rather than do anything to reverse it. “They had become poor and shabby without noticing … accustomed to disrepair”; theirs is a “personalized squalor.”

Bell and Sigh become increasingly hermit-like, with entrenched ways of doing things. Baume several times describes their compost bin, which struck me as a perfect image for how the stuff of daily life builds up and beds down into the foundation of personalities and a relationship. The fact that they only have each other (and the dogs) for company explains how they adopt each other’s mannerisms, develop a private language, and even conflate their separate memories. The starkest symbol of their refusal of societal norms comes when they miss a clock change and effectively live in their own time zone.

Bell and Sigh become increasingly hermit-like, with entrenched ways of doing things. Baume several times describes their compost bin, which struck me as a perfect image for how the stuff of daily life builds up and beds down into the foundation of personalities and a relationship. The fact that they only have each other (and the dogs) for company explains how they adopt each other’s mannerisms, develop a private language, and even conflate their separate memories. The starkest symbol of their refusal of societal norms comes when they miss a clock change and effectively live in their own time zone.

I recognized from Spill Simmer Falter Wither and handiwork several elements that reflect Baume’s interests: nature imagery, dogs, and daily routines. She gives a clear sense of time’s passage and the seasons’ turning, of repetition and attrition and ageing. I wearied of the descriptive passages and hoped that at some point there would be some action and dialogue to counterbalance them, but that is not what this novel is about. Occasional flashes from the point-of-view of a mouse in the house, or a spider in the van, tell you that Baume’s scope is wider. This is in fact an allegory about impermanence, from a mountain’s-eye view.

Although I was frustrated with the central characters’ jolly incompetence (“Just buy leashes and a tick twister, you idiots!” I felt like shouting at them after yet another mention of the dogs killing cats and rabbits; and of the difficulty of removing ticks from their coats), I recognized how easy it is to get stuck in lazy habits; how easy it is to live provisionally, as if all is temporary and not your real existence.

Baume spaces lines and paragraphs almost like hybrid poetry and indulges in overwriting in places. Because of the dearth of action, this was a slog of a months-long read for me, but I admired it in the end and enjoyed it more than the other two books of hers that I’ve read.

If you admire lyrical prose and are okay with little to no plot in a novel, you should get on fine with this one. Or it might be that it requires the right time or reading mood, when you’re after something quiet.

Having read more by Dylan Thomas now, I think this is exactly the sort of place-specific and playful, stylized prose that the prize named after him is looking for. So, I’ll predict Baume as the winner.

With thanks to Tramp Press for the free e-copy for review.

I’m a Fan by Sheena Patel

This was one of my correct predictions for the Women’s Prize longlist; I’d heard a lot about it from Best of 2022 roundups and it seemed like the kind of edgy title they might recognise. It’s also perfect for the Dylan Thomas Prize list because of how voice-driven it is. The unnamed narrator, a woman of colour in her early thirties, muses on art, entitlement, obsession, social media and sex in short titled sections ranging from one paragraph to a few pages long. The twin objects of her fanaticism are “the man I want to be with,” who is married and generally keeps her at arm’s length, and “the woman I am obsessed with,” a lifestyle influencer who, like herself, is one of this man’s girlfriends on the side. She stalks the woman via her impeccably curated Instagram images.

The narrator has a boyfriend, in fact, a peculiarly perfect-sounding one even, but takes him for granted in her compulsive search for indiscriminate sexual experience (also including a female co-worker she calls “the Peach”). They end up parting ways and she moves back in with her parents, an ignominious retreat from attempted adulting.

The narrator has a boyfriend, in fact, a peculiarly perfect-sounding one even, but takes him for granted in her compulsive search for indiscriminate sexual experience (also including a female co-worker she calls “the Peach”). They end up parting ways and she moves back in with her parents, an ignominious retreat from attempted adulting.

She reminded me a bit of Bell and Sigh for her haplessness, but whereas the matter of having children literally never arises for them, the question of motherhood is a background niggle for her (“I thought I had the rest of my life to make this decision but I realise I am on a clock and it runs differently for me. I am female. There was never much time and I’ve wasted so much already”; “I want to gain immortality because of my brain and not because of the potential of my womb”). As the novella goes on, she even considers weaponising her fertility as a way of entrapping her crush.

I was reasonably engaged with the narrator’s deliberations about taste and autobiographical influences, but overall found this rather indulgent, slight and repetitive. Books about social media – this reminded me most of Adults by Emma Jane Unsworth – are in danger of becoming irrelevant all too quickly. The sexual frankness fell on the wrong side of unpleasant for me, and the format for referring to other characters leads to inelegant phrasing like “The man I want to be with’s work centres around conflict”. Something like Luster has that little bit more individuality and energy. (Secondhand – charity shop purchase)

Rathbones Folio Prize Fiction Shortlist: Sheila Heti and Elizabeth Strout

I’ve enjoyed engaging with this year’s Rathbones Folio Prize shortlists, reading the entire poetry shortlist and two each from the nonfiction and fiction lists. These two I accessed from the library. Both Sheila Heti and Elizabeth Strout featured in the 5×15 event I attended on Tuesday evening, so in the reviews below I’ll weave in some insights from that.

Pure Colour by Sheila Heti

Sheila Heti is a divisive author; I’m sure there are those who detest her indulgent autofiction, though I’ve loved it (How Should a Person Be? and especially Motherhood). But this is another thing entirely: Heti puts two fingers up to the whole notion of rounded characterization or coherent plot. This is the thinnest of fables, fascinating for its ideas and certainly resonant for me what with the themes of losing a parent and searching for purpose in life on an earth that seems doomed to destruction … but is it a novel?

Sheila Heti is a divisive author; I’m sure there are those who detest her indulgent autofiction, though I’ve loved it (How Should a Person Be? and especially Motherhood). But this is another thing entirely: Heti puts two fingers up to the whole notion of rounded characterization or coherent plot. This is the thinnest of fables, fascinating for its ideas and certainly resonant for me what with the themes of losing a parent and searching for purpose in life on an earth that seems doomed to destruction … but is it a novel?

My summary for Bookmarks magazine gives an idea of the ridiculous plot:

Heti imagines that the life we live now—for Mira, studying at the American Academy of American Critics, working in a lamp store, grieving her father, and falling in love with Annie—is just God’s first draft. In this creation myth of sorts, everyone is born a “bear” (lover), “bird” (achiever), or “fish” (follower). Mira has a mystical experience in which she and her dead father meet as souls in a leaf, where they converse about the nature of time and how art helps us face the inevitability of death. If everything that exists will soon be wiped out, what matters?

The three-creature classification is cute enough, but a copout because it means Heti doesn’t have to spend time developing Mira (a bird), Annie (a fish), or Mira’s father (a bear), except through surreal philosophical dialogues that may or may not take place whilst she is disembodied in a leaf. It’s also uncomfortable how Heti uses sexual language for Mira’s communion with her dead dad: “she knew that the universe had ejaculated his spirit into her”.

Heti explained that the book came to her in discrete chunks, from what felt like a more intuitive place than the others, which were more of an intellectual struggle, and that she drew on her own experience of grief over her father’s death, though she had been writing it for a year beforehand.

Indeed, she appears to be tapping into primordial stories, the stuff of Greek myth or Jewish kabbalah. She writes sometimes of “God” and sometimes of “the gods”: the former regretting this first draft of things and planning how to make things better for himself the second time around; the latter out to strip humans of what they care about: “our parents, our ambitions, our friendships, our beauty—different things from different people. They strip some people more and others less. They strip us of whatever they need to in order to see us more clearly.” Appropriately, then, we follow Mira all the way through to her end, when, stripped of everything but love, she rediscovers the two major human connections of her life.

Given Ali Smith’s love of the experimental, it’s no surprise that she as a judge shortlisted this. If you’re of a philosophical bent, don’t mind negligible/non-existent plot in your novels and aren’t turned off by literary pretension, you should be fine. If you are new to Heti or unsure about trying her, though, this is probably not the right place to start. See my Goodreads review for some sample quotes, good and bad.

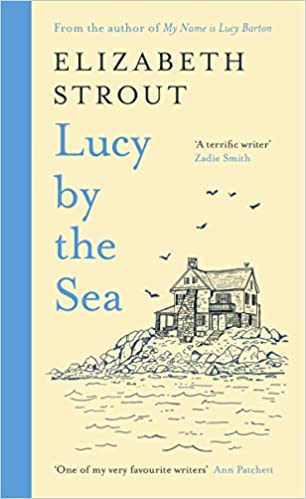

Lucy by the Sea by Elizabeth Strout

This was by far the best of the three Amgash books I’ve read. I think it must be the first time that Strout has set a book not in the past or at some undated near-contemporary moment but in the actual world with its current events, which inevitably means it gets political. I had my doubts about how successful she’d be with such hyper-realism, but this really worked.

As Covid hits, William whisks Lucy away from her New York City apartment to a house at the coast in Crosby, Maine. She’s an Everywoman recounting the fear and confusion of those early pandemic days, hearing of friends and relatives falling ill and knowing there’s nothing she can do about it. Isolation, mostly imposed on her but partially chosen – she finally gets a writing studio, the first ‘room of her own’ she’s ever had – gives her time to ponder the trauma of her childhood and what went wrong in her marriage to William. She worries for her two adult daughters but, for the first time, you get the sense that the strength and wisdom she’s earned through bitter experience will help her support them in making good choices.

As Covid hits, William whisks Lucy away from her New York City apartment to a house at the coast in Crosby, Maine. She’s an Everywoman recounting the fear and confusion of those early pandemic days, hearing of friends and relatives falling ill and knowing there’s nothing she can do about it. Isolation, mostly imposed on her but partially chosen – she finally gets a writing studio, the first ‘room of her own’ she’s ever had – gives her time to ponder the trauma of her childhood and what went wrong in her marriage to William. She worries for her two adult daughters but, for the first time, you get the sense that the strength and wisdom she’s earned through bitter experience will help her support them in making good choices.

Here in rural Maine, Lucy sees similar deprivation to what she grew up with in Illinois and also meets real people – nice, friendly people – who voted for Trump and refuse to be vaccinated. I loved how Strout shows us Lucy observing and then, through a short story, compassionately imagining herself into the situation of conservative cops and drug addicts. “Try to go outside your comfort level, because that’s where interesting things will happen on the page,” is her philosophy. This felt like real insight into a writer’s inspirations.

Another neat thing Strout does here, as she has done before, is to stitch her oeuvre together by including references to most of her other books. So she becomes friends with Bob Burgess, volunteers alongside Olive Kitteridge’s nursing home caregiver (and I expect their rental house is supposed to be the one Olive vacated), and meets the pastor’s daughter from Abide with Me. My only misgiving is that she recounts Bob Burgess’s whole story, replete with spoilers, such that I don’t feel I need to read The Burgess Boys.

Lucy has emotional intelligence (“You’re not stupid about the human heart,” Bob Burgess tells her) and real, hard-won insight into herself (“My childhood had been a lockdown”). Readers as well as writers have really taken this character to heart, admiring her seemingly effortless voice. Strout said she does not think of this as a ‘pandemic novel’ because she’s always most interested in character. She believes the most important thing is the sound of the sentences and that a writer has to determine the shape of the material from the inside. She was very keen to separate herself from Lucy, and in fact came across as rather terse. I had somehow expected her to have a higher voice, to be warmer and softer. (“Ah, you’re not Lucy, you’re Olive!” I thought to myself.)

Predictions

This year’s judges are Guy Gunaratne, Jackie Kay and Ali Smith. Last year’s winner was a white man, so I’m going to say in 2023 the prize should go to a woman of colour, and in fact I wouldn’t be surprised if all three category winners were women of colour. My own taste in the shortlists is, perhaps unsurprisingly, very white-lady-ish and non-experimental. But I think Amy Bloom and Elizabeth Strout’s books are too straightforward and Fiona Benson’s not edgy enough. So I’m expecting:

Fiction: Scary Monsters by Michelle de Kretser

Nonfiction: Constructing a Nervous System by Margo Jefferson

Poetry: Quiet by Victoria Adukwei Bulley (or Cane, Corn & Gully by Safiya Kamaria Kinshasa)

Overall winner: Constructing a Nervous System by Margo Jefferson (or Quiet by Victoria Adukwei Bulley)

This is my 1,200th blog post!

This debut novel is cleverly set within the month of Ramadan, a time of abstention. In this way, Gawad emphasizes the tension between faith and the temptations of alcohol and sex. Egyptian-American twin sisters Amira and Lina Emam are on the cusp, about to graduate from high school and go their separate ways. Lina wants to be a model and is dating a nightclub manager she hopes can make this a reality; Amira, ever the sensible one, is college-bound. But then she meets her first boyfriend, Faraj, and lets Lina drag her into a reckless partying lifestyle. “I was seized with that summertime desire of girls: to push my body to its limits.” Meanwhile, the girls’ older brother, Sami, just home from prison, is finding it a challenge to integrate back into the family and their Bay Ridge mosque, reeling from a raid on a Muslim-owned neighbourhood business and a senseless attack on the old imam.

This debut novel is cleverly set within the month of Ramadan, a time of abstention. In this way, Gawad emphasizes the tension between faith and the temptations of alcohol and sex. Egyptian-American twin sisters Amira and Lina Emam are on the cusp, about to graduate from high school and go their separate ways. Lina wants to be a model and is dating a nightclub manager she hopes can make this a reality; Amira, ever the sensible one, is college-bound. But then she meets her first boyfriend, Faraj, and lets Lina drag her into a reckless partying lifestyle. “I was seized with that summertime desire of girls: to push my body to its limits.” Meanwhile, the girls’ older brother, Sami, just home from prison, is finding it a challenge to integrate back into the family and their Bay Ridge mosque, reeling from a raid on a Muslim-owned neighbourhood business and a senseless attack on the old imam.

You Were Watching from the Sand by Juliana Lamy – I read the first 22% of this short fiction collection, which equated to a brief opener in the second person about a situation of abuse, followed by part of one endless-feeling story based around one apartment and bodega and featuring two young female family friends, one of whom accepts sexual favours in the supply closet from most male visitors. The voice and prose didn’t grab me, but of course I can’t say whether later stories would have been more to my taste. (Edelweiss)

You Were Watching from the Sand by Juliana Lamy – I read the first 22% of this short fiction collection, which equated to a brief opener in the second person about a situation of abuse, followed by part of one endless-feeling story based around one apartment and bodega and featuring two young female family friends, one of whom accepts sexual favours in the supply closet from most male visitors. The voice and prose didn’t grab me, but of course I can’t say whether later stories would have been more to my taste. (Edelweiss)

The protagonist is ‘Amy’, who lives in a tornado-ridden Oklahoma and whose sister, ‘Zoe’ – a handy A to Z of growing up there – has a mysterious series of illnesses that land her in hospital. The third person limited perspective reveals Amy to be a protective big sister who shoulders responsibility: “There is nothing in the world worse than Zoe having her blood drawn. Amy tries to show her the pictures [she’s taken of Zoe’s dog] at just the right moment, just right before the nurse puts the needle in”.

The protagonist is ‘Amy’, who lives in a tornado-ridden Oklahoma and whose sister, ‘Zoe’ – a handy A to Z of growing up there – has a mysterious series of illnesses that land her in hospital. The third person limited perspective reveals Amy to be a protective big sister who shoulders responsibility: “There is nothing in the world worse than Zoe having her blood drawn. Amy tries to show her the pictures [she’s taken of Zoe’s dog] at just the right moment, just right before the nurse puts the needle in”.

In 2017 I reviewed Grudova’s surreal story collection,

In 2017 I reviewed Grudova’s surreal story collection,  Lucrezia di Cosimo de’ Medici is a historical figure who died at age 16, having been married off from her father’s Tuscan palazzo as a teenager to Alfonso II d’Este, Duke of Ferrara. She was reported to have died of a “putrid fever” but the suspicion has persisted that her husband actually murdered her, a story perhaps best known via Robert Browning’s poem “My Last Duchess.”

Lucrezia di Cosimo de’ Medici is a historical figure who died at age 16, having been married off from her father’s Tuscan palazzo as a teenager to Alfonso II d’Este, Duke of Ferrara. She was reported to have died of a “putrid fever” but the suspicion has persisted that her husband actually murdered her, a story perhaps best known via Robert Browning’s poem “My Last Duchess.”

Ghostwriter Ida’s section was much my favourite, for her voice as well as for how it leads you to go back to the previous part – some of it still in shorthand (“Father. Describe early memories of him. … MATH in great detail. Precocious talent. Anecdotes.”) and reassess its picture of Bevel. His short selling in advance of the Great Depression made him a fortune, but he defends himself: “My actions safeguarded American industry and business.” Mildred’s journal entries, clearly written through a fog of pain as she was dying from cancer, then force another rethink about the role she played in her husband’s decision making. With her genius-level memory, philanthropy and love of literature and music, she’s a much more interesting character than Bevel – that being the point, of course, that he steals the limelight. This is clever, clever stuff. However, as admirable as the pastiche sections might be (though they’re not as convincing as the first section of

Ghostwriter Ida’s section was much my favourite, for her voice as well as for how it leads you to go back to the previous part – some of it still in shorthand (“Father. Describe early memories of him. … MATH in great detail. Precocious talent. Anecdotes.”) and reassess its picture of Bevel. His short selling in advance of the Great Depression made him a fortune, but he defends himself: “My actions safeguarded American industry and business.” Mildred’s journal entries, clearly written through a fog of pain as she was dying from cancer, then force another rethink about the role she played in her husband’s decision making. With her genius-level memory, philanthropy and love of literature and music, she’s a much more interesting character than Bevel – that being the point, of course, that he steals the limelight. This is clever, clever stuff. However, as admirable as the pastiche sections might be (though they’re not as convincing as the first section of  That GMB is quite the trickster. From the biographical sections, I definitely assumed that A. Collins Braithwaite was a real psychiatrist in the 1960s. A quick Google when I got to the end revealed that he only exists in this fictional universe. I enjoyed the notebooks recounting an unnamed young woman’s visits to Braithwaite’s office; holding the man responsible for her sister’s suicide, she books her appointments under a false name, Rebecca Smyth, and tries acting just mad (and sensual) enough to warrant her coming back. Her family stories, whether true or embellished, are ripe for psychoanalysis, and the more she inhabits this character she’s created the more she takes on her persona. (“And, perhaps on account of Mrs du Maurier’s novel, Rebecca had always struck me as the most dazzling of names. I liked the way its three short syllables felt in my mouth, ending in that breathy, open-lipped exhalation.” I had to laugh at this passage! I’ve always thought mine a staid name.) But the different documents don’t come together as satisfyingly as I expected, especially compared to

That GMB is quite the trickster. From the biographical sections, I definitely assumed that A. Collins Braithwaite was a real psychiatrist in the 1960s. A quick Google when I got to the end revealed that he only exists in this fictional universe. I enjoyed the notebooks recounting an unnamed young woman’s visits to Braithwaite’s office; holding the man responsible for her sister’s suicide, she books her appointments under a false name, Rebecca Smyth, and tries acting just mad (and sensual) enough to warrant her coming back. Her family stories, whether true or embellished, are ripe for psychoanalysis, and the more she inhabits this character she’s created the more she takes on her persona. (“And, perhaps on account of Mrs du Maurier’s novel, Rebecca had always struck me as the most dazzling of names. I liked the way its three short syllables felt in my mouth, ending in that breathy, open-lipped exhalation.” I had to laugh at this passage! I’ve always thought mine a staid name.) But the different documents don’t come together as satisfyingly as I expected, especially compared to

She may be only 20 years old, but Leila Mottley is the real deal. Her debut novel, laden with praise from her mentor Ruth Ozeki and many others, reminded me of Bryan Washington’s work. The first-person voice is convincing and mature as Mottley spins the (inspired by a true) story of an underage prostitute who testifies against the cops who have kept her in what is virtually sex slavery. At 17, Kiara is the de facto head of her household, with her father dead, her mother in a halfway house, and her older brother pursuing his dream of recording a rap album. When news comes of a rise in the rent and Kia stumbles into being paid for sex, she knows it’s her only way of staying in their Oakland apartment and looking after her neglected nine-year-old neighbour, Trevor.

She may be only 20 years old, but Leila Mottley is the real deal. Her debut novel, laden with praise from her mentor Ruth Ozeki and many others, reminded me of Bryan Washington’s work. The first-person voice is convincing and mature as Mottley spins the (inspired by a true) story of an underage prostitute who testifies against the cops who have kept her in what is virtually sex slavery. At 17, Kiara is the de facto head of her household, with her father dead, her mother in a halfway house, and her older brother pursuing his dream of recording a rap album. When news comes of a rise in the rent and Kia stumbles into being paid for sex, she knows it’s her only way of staying in their Oakland apartment and looking after her neglected nine-year-old neighbour, Trevor. This was a DNF for me last year, but I tried again. The setup is simple: Lucy Barton’s ex-husband, William, discovers he has a half-sister he never knew about. William and Lucy travel from New York City to Maine in hopes of meeting her. For both of them, the quest sparks a lot of questions about how our origins determine who we are, and what William’s late mother, Catherine, was running from and to in leaving her husband and small child behind to forge a different life. Like Lucy, Catherine came from nothing; to an extent, everything that unfolded afterwards for them was a reaction against poverty and neglect.

This was a DNF for me last year, but I tried again. The setup is simple: Lucy Barton’s ex-husband, William, discovers he has a half-sister he never knew about. William and Lucy travel from New York City to Maine in hopes of meeting her. For both of them, the quest sparks a lot of questions about how our origins determine who we are, and what William’s late mother, Catherine, was running from and to in leaving her husband and small child behind to forge a different life. Like Lucy, Catherine came from nothing; to an extent, everything that unfolded afterwards for them was a reaction against poverty and neglect.

Our joint highest rating, and one of our best discussions – taking in mental illness and its diagnosis and treatment, marriage, childlessness, alcoholism, sisterhood, creativity, neglect, unreliable narrators and loneliness. For several of us, these issues hit close to home due to personal or family experience. We particularly noted the way that Mason sets up parallels between pairs of characters, accurately reflecting how family dynamics can be replicated in later generations.

Our joint highest rating, and one of our best discussions – taking in mental illness and its diagnosis and treatment, marriage, childlessness, alcoholism, sisterhood, creativity, neglect, unreliable narrators and loneliness. For several of us, these issues hit close to home due to personal or family experience. We particularly noted the way that Mason sets up parallels between pairs of characters, accurately reflecting how family dynamics can be replicated in later generations.