20 Books of Summer, 14–16: Polly Atkin, Nan Shepherd and Susan Allen Toth

I’m still plugging away at the challenge. It’ll be down to the wire, but I should finish and review all 20 books by the 31st! Today I have a chronic illness memoir, a collection of poetry and prose pieces, and a reread of a cosy travel guide.

Some of Us Just Fall: On Nature and Not Getting Better by Polly Atkin (2023)

I was heartened to see this longlisted for the Wainwright Prize. It was a perfect opportunity to recognize the disabled/chronically ill experience of nature and the book achieves just what the award has recognised in recent years: the braiding together of life writing and place-based observation. (Wainwright has also done a great job on diversity this year: there are three books by BIPOC and five by women on the nature writing shortlist alone.)

Polly Atkin knew something was different about her body from a young age. She broke bones all the time, her first at 18 months when her older brother ran into her on his bicycle. But it wasn’t until her thirties that she knew what was wrong – Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and haemochromatosis – and developed strategies to mitigate the daily pain and the drains on her energy and mobility. “Correct diagnosis makes lives bearable,” she writes. “It gives you access to the right treatment. It gives you agency.”

Polly Atkin knew something was different about her body from a young age. She broke bones all the time, her first at 18 months when her older brother ran into her on his bicycle. But it wasn’t until her thirties that she knew what was wrong – Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and haemochromatosis – and developed strategies to mitigate the daily pain and the drains on her energy and mobility. “Correct diagnosis makes lives bearable,” she writes. “It gives you access to the right treatment. It gives you agency.”

The book assembles long-ish fragments, snippets from different points of her past alternating with what she sees on rambles near her home in Grasmere. She writes in some depth about Lake District literature: Thomas De Quincey as well as the Wordsworths – Atkin’s previous book is a biography of Dorothy Wordsworth that spotlights her experience with illness. In describing the desperately polluted state of Windermere, Atkin draws parallels with her condition (“Now I recognise my body as a precarious ecosystem”). Although she spurns the notion of the “Nature Cure,” swimming is a valuable therapy for her.

Theme justifies form here: “This is the chronic life, lived as repetition and variance, as sedimentation of broken moments, not as a linear progression.” For me, there was a bit too much particularity; if you don’t connect to the points of reference, there’s no way in and the danger arises of it all feeling indulgent. Besides, by the time I opened this I’d already read two Ehlers-Danlos memoirs (All My Wild Mothers by Victoria Bennett and Floppy by Alyssa Graybeal) and another reference soon came my way in The Invisible Kingdom by Meghan O’Rourke. So overfamiliarity was a problem. And by the time I forced myself to pick this off of my set-aside shelf and finish it, I’d read Nina Lohman’s stellar The Body Alone. For those newer to reading about chronic illness, though, especially if you also have an interest in the Lakes, it could be an eye-opener.

With thanks to Sceptre (Hodder) for the free copy for review.

Selected Prose & Poetry by Nan Shepherd (2023)

I’d read and enjoyed Shepherd’s The Living Mountain, which has surged in popularity as an early modern nature writing classic thanks to Robert Macfarlane et al. I’m not sure I’d go as far as the executor of the Nan Shepherd Estate, though, who describes her in the Preface as “Taylor Swift in hiking boots.” The pieces reprinted here are from her one published book of poems, In the Cairngorms, and the mixed-genre collection Wild Geese. There is also a 28-page “novella,” Descent from the Cross. After World War I, Elizabeth, a workers’ rights organiser for a paper mill, marries a shell-shocked veteran who wants to write a book but isn’t sure he has either the genius or the dedication. It’s interesting that Shepherd would write about a situation where the wife has the economic upper hand, but the tragedy of the sickly failed author put me in mind of George Gissing or D.H. Lawrence, so didn’t feel fresh. Going by length alone, I would have called this a short story, but I understand why it would be designated a novella, for the scope.

I’d read and enjoyed Shepherd’s The Living Mountain, which has surged in popularity as an early modern nature writing classic thanks to Robert Macfarlane et al. I’m not sure I’d go as far as the executor of the Nan Shepherd Estate, though, who describes her in the Preface as “Taylor Swift in hiking boots.” The pieces reprinted here are from her one published book of poems, In the Cairngorms, and the mixed-genre collection Wild Geese. There is also a 28-page “novella,” Descent from the Cross. After World War I, Elizabeth, a workers’ rights organiser for a paper mill, marries a shell-shocked veteran who wants to write a book but isn’t sure he has either the genius or the dedication. It’s interesting that Shepherd would write about a situation where the wife has the economic upper hand, but the tragedy of the sickly failed author put me in mind of George Gissing or D.H. Lawrence, so didn’t feel fresh. Going by length alone, I would have called this a short story, but I understand why it would be designated a novella, for the scope.

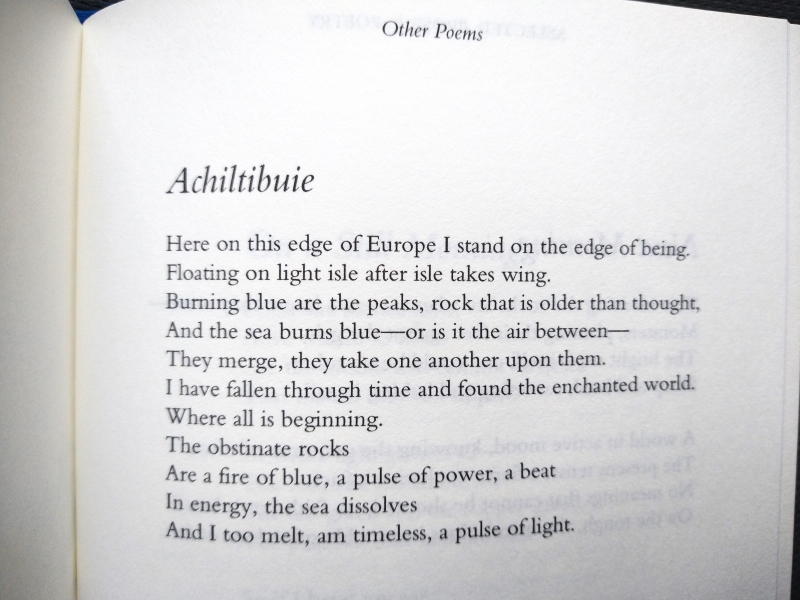

None of the miniature essays – field observations and character studies – stood out to me. About half of the book is given over to poetry. As with the nature writing, there is a feeling of mountain desolation. There are a lot of religious references and hints of the mystical, as in “The Bush,” which opens “In that pure ecstasy of light / The bush is burning bright. / Its substance is consumed away / And only form doth stay”. It’s a mixed bag: some feels very old-fashioned and sentimental, with every other line or, worse, every line rhyming, and some archaic wording and rather impenetrable Scots dialect. It could have been written 100 years before, by Robert Burns if not William Blake. But every so often there is a flash of brilliance. “Blackbird in Snow” is quite a nice one, and reminiscent of Thomas Hardy’s “The Darkling Thrush.” I even found the cryptic lines from “Real Presence” that inspired a song on David Gray’s Skellig. My favourite poem by far was:

Overall, this didn’t engage me; it’s only for Shepherd fanatics and completists. (Won from Galileo Publishers in a Twitter giveaway)

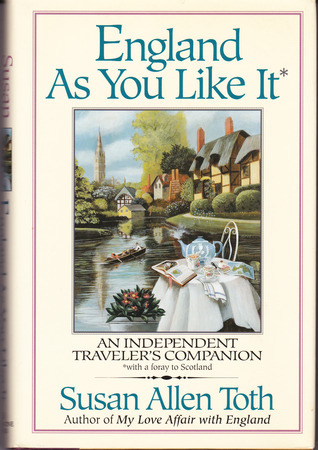

England As You Like It: An Independent Traveler’s Companion by Susan Allen Toth (1995)

A reread. As I was getting ready to go overseas for the first time in the summer of 2003, Toth’s trilogy of memoirs whetted my appetite for travel in Britain. (They’re on my Landmark Books in My Life, Part II list.) This is the middle book and probably the least interesting in that it mostly recounts stays in particular favourite locations, such as Dorset, the Highlands, and various sites in Cornwall. However, I’ve never forgotten her “thumbprint theory,” which means staying a week or more in an area no larger than her thumb covers on a large-scale map, driving an hour or less for day trips. Not for her those cram-it-all-in trips where you race through multiple countries in a week (I have American friends who did Paris, London and Rome within six days, or five countries in eight days; blame it on stingy vacation policies, I guess). Instead, she wants to really bed into one place and have the time to make serendipitous discoveries such as an obscure museum or a rare opening of a private garden.

A reread. As I was getting ready to go overseas for the first time in the summer of 2003, Toth’s trilogy of memoirs whetted my appetite for travel in Britain. (They’re on my Landmark Books in My Life, Part II list.) This is the middle book and probably the least interesting in that it mostly recounts stays in particular favourite locations, such as Dorset, the Highlands, and various sites in Cornwall. However, I’ve never forgotten her “thumbprint theory,” which means staying a week or more in an area no larger than her thumb covers on a large-scale map, driving an hour or less for day trips. Not for her those cram-it-all-in trips where you race through multiple countries in a week (I have American friends who did Paris, London and Rome within six days, or five countries in eight days; blame it on stingy vacation policies, I guess). Instead, she wants to really bed into one place and have the time to make serendipitous discoveries such as an obscure museum or a rare opening of a private garden.

I most liked the early general chapters about how to make air travel bearable, her obsession with maps, her preference for self-catering, and her tendency to take home edible souvenirs. Of course, all the “Floating Facts” are hopelessly out-of-date. This being the early to mid-1990s, she had to order paper catalogues to browse cottage options (I still did this for honeymoon prep in 2006–7) and make international phone calls to book accommodation. She recommends renting somewhere from the National Trust or Landmark Trust. Ordnance Survey maps could be special ordered from the British Travel Bookshop in New York City. Entry fees averaged a few pounds. It’s all so quaint! An Anglo-American time capsule of sorts. I’ve always sensed a kindred spirit in Toth, and those whose taste runs toward the old-fashioned will probably also find her a charming tour guide. I’ve also reviewed the third book, England for All Seasons. (Free from The Book Thing of Baltimore)

Small Rain by Garth Greenwell: A poet and academic (who both is and is not Greenwell) endures a Covid-era medical crisis that takes him to the brink of mortality and the boundary of survivable pain. Over two weeks, we become intimately acquainted with his every test, intervention, setback and fear. Experience is clarified precisely into fluent language that also flies far above a hospital bed, into a vibrant past, a poetic sensibility, a hoped-for normality. I’ve never read so remarkable an account of what it is to be a mind in a fragile body.

Small Rain by Garth Greenwell: A poet and academic (who both is and is not Greenwell) endures a Covid-era medical crisis that takes him to the brink of mortality and the boundary of survivable pain. Over two weeks, we become intimately acquainted with his every test, intervention, setback and fear. Experience is clarified precisely into fluent language that also flies far above a hospital bed, into a vibrant past, a poetic sensibility, a hoped-for normality. I’ve never read so remarkable an account of what it is to be a mind in a fragile body.