Women’s Prize for Non-Fiction, Writers’ Prize & Young Writer of the Year Award Catch-Up

This time of year, it’s hard to keep up with all of the literary prize announcements: longlists, shortlists, winners. I’m mostly focussing on the Carol Shields Prize for Fiction this year, but I like to dip a toe into the others where I can. I ask: What do I have time to read? What can I find at the library? and Which books are on multiple lists so I can tick off several at a go??

Women’s Prize for Non-Fiction

(Shortlist to be announced on 27 March.)

Read so far: Intervals by Marianne Brooker, Matrescence by Lucy Jones

&

A Flat Place by Noreen Masud

Past: Sunday Times/Charlotte Aitken Young Writer of the Year Award shortlist

Currently: Jhalak Prize longlist

I also expect this to be a strong contender for the Wainwright Prize for nature writing, and hope it doesn’t end up being a multi-prize bridesmaid as it is an excellent book but an unusual one that is hard to pin down by genre. Most simply, it is a travel memoir taking in flat landscapes of the British Isles: the Cambridgeshire fens, Orford Ness in Suffolk, Morecambe Bay, Newcastle Moor, and the Orkney Islands.

But flatness is a psychological motif as well as a physical reality here. Growing up in Pakistan with a violent Pakistani father and a passive Scottish mother, Masud chose the “freeze” option when in fight-or-flight situations. When she was 15, her father disowned her and she moved with her mother and sisters to Scotland. Though no particularly awful things happened, a childhood lack of safety, belonging and love left her with complex PTSD that still affects how she relates to her body and to other people, even after her father’s death.

But flatness is a psychological motif as well as a physical reality here. Growing up in Pakistan with a violent Pakistani father and a passive Scottish mother, Masud chose the “freeze” option when in fight-or-flight situations. When she was 15, her father disowned her and she moved with her mother and sisters to Scotland. Though no particularly awful things happened, a childhood lack of safety, belonging and love left her with complex PTSD that still affects how she relates to her body and to other people, even after her father’s death.

Masud is clear-eyed about her self and gains a new understanding of what her mother went through during their trip to Orkney. The Newcastle chapter explores lockdown as a literal Covid-era circumstance but also as a state of mind – the enforced solitude and stillness suited her just fine. Her descriptions of landscapes and journeys are engaging and her metaphors are vibrant: “South Nuns Moor stretched wide, like mint in my throat”; “I couldn’t stop thinking about the Holm of Grimbister, floating like a communion wafer on the blue water.” Although she is an academic, her language is never off-puttingly scholarly. There is a political message here about the fundamental trauma of colonialism and its ongoing effects on people of colour. “I don’t want ever to be wholly relaxed, wholly at home, in a world of flowing fresh water built on the parched pain of others,” she writes.

What initially seems like a flat authorial affect softens through the book as Masud learns strategies for relating to her past. “All families are cults. All parents let their children down.” Geography, history and social justice are all a backdrop for a stirring personal story. Literally my only annoyance was the pseudonyms she gives to her sisters (Rabbit, Spot and Forget-Me-Not). (Read via Edelweiss) ![]()

And a quick skim:

Doppelganger: A Trip into the Mirror World by Naomi Klein

Past: Writers’ Prize shortlist, nonfiction category

For years people have been confusing Naomi Klein (geography professor, climate commentator, author of No Logo, etc.) with Naomi Wolf (feminist author of The Beauty Myth, Vagina, etc.). This became problematic when “Other Naomi” espoused various right-wing conspiracy theories, culminating with allying herself with Steve Bannon in antivaxxer propaganda. Klein theorizes on Wolf’s ideological journey and motivations, weaving in information about the doppelganger in popular culture (e.g., Philip Roth’s novels) and her own concerns about personal branding. I’m not politically minded enough to stay engaged with this but what I did read I found interesting and shrewdly written. I do wonder how her publisher was confident this wouldn’t attract libel allegations? (Public library)

For years people have been confusing Naomi Klein (geography professor, climate commentator, author of No Logo, etc.) with Naomi Wolf (feminist author of The Beauty Myth, Vagina, etc.). This became problematic when “Other Naomi” espoused various right-wing conspiracy theories, culminating with allying herself with Steve Bannon in antivaxxer propaganda. Klein theorizes on Wolf’s ideological journey and motivations, weaving in information about the doppelganger in popular culture (e.g., Philip Roth’s novels) and her own concerns about personal branding. I’m not politically minded enough to stay engaged with this but what I did read I found interesting and shrewdly written. I do wonder how her publisher was confident this wouldn’t attract libel allegations? (Public library) ![]()

Predictions: Cumming (see below) and Klein are very likely to advance. I’m less drawn to the history or popular science/tech titles. I’d most like to read Some People Need Killing: A Memoir of Murder in the Philippines by Patricia Evangelista, Wifedom: Mrs Orwell’s Invisible Life by Anna Funder, and How to Say Babylon: A Jamaican Memoir by Safiya Sinclair. I’d be delighted for Brooker, Jones and Masud to be on the shortlist. Three or more by BIPOC would seem appropriate. I expect they’ll go for diversity of subject matter as well.

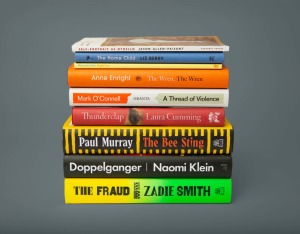

Writers’ Prize

Last year I read most books from the shortlists and so was able to make informed (and, amazingly, thoroughly correct) predictions of the winners. I didn’t do as well this year. In particular, I failed with the nonfiction list in that I DNFed Mark O’Connell’s book and twice borrowed the Cumming from the library but never managed to make myself start it; I thought her On Chapel Sands overrated. (I did skim the Klein, as above.) But at least I read the poetry shortlist in full:

Self-Portrait as Othello by Jason Allen-Paisant: I found more to sink my teeth into here than I did with his debut collection, Thinking with Trees (2021). Part I’s childhood memories of Jamaica open out into a wider world as the poet travels to London, Paris and Venice, working in snippets of French and Italian and engaging with art and literature. “I’m haunted as much by the character Othello as by the silences in the story.” Part III returns home for the death of his grandmother and a coming to terms with identity. [Winner: Forward Prize for Best Collection; Past: T.S. Eliot Prize shortlist] (Public library)

Self-Portrait as Othello by Jason Allen-Paisant: I found more to sink my teeth into here than I did with his debut collection, Thinking with Trees (2021). Part I’s childhood memories of Jamaica open out into a wider world as the poet travels to London, Paris and Venice, working in snippets of French and Italian and engaging with art and literature. “I’m haunted as much by the character Othello as by the silences in the story.” Part III returns home for the death of his grandmother and a coming to terms with identity. [Winner: Forward Prize for Best Collection; Past: T.S. Eliot Prize shortlist] (Public library) ![]()

The Home Child by Liz Berry: A novel in verse “loosely inspired,” as Berry puts it, by her great-aunt Eliza Showell’s experience: she was a 12-year-old orphan when, in 1908, she was forcibly migrated from the English Midlands to Nova Scotia. The scenes follow her from her home to the Children’s Emigration Home in Birmingham, on the sea voyage, and in her new situation as a maid to an elderly invalid. Life is gruelling and lonely until a boy named Daniel also comes to the McPhail farm. This was a slow and not especially engaging read because of the use of dialect, which for me really got in the way of the story. (Public library)

The Home Child by Liz Berry: A novel in verse “loosely inspired,” as Berry puts it, by her great-aunt Eliza Showell’s experience: she was a 12-year-old orphan when, in 1908, she was forcibly migrated from the English Midlands to Nova Scotia. The scenes follow her from her home to the Children’s Emigration Home in Birmingham, on the sea voyage, and in her new situation as a maid to an elderly invalid. Life is gruelling and lonely until a boy named Daniel also comes to the McPhail farm. This was a slow and not especially engaging read because of the use of dialect, which for me really got in the way of the story. (Public library) ![]()

& Bright Fear by Mary Jean Chan (Current: Dylan Thomas Prize shortlist)

& Bright Fear by Mary Jean Chan (Current: Dylan Thomas Prize shortlist) ![]()

Three category winners:

- The Wren, The Wren by Anne Enright (Fiction)

- Thunderclap by Laura Cumming (Nonfiction) (Current: Women’s Prize for Non-Fiction longlist)

- The Home Child by Liz Berry (Poetry)

Overall winner: The Home Child by Liz Berry

Observations: The academy values books that cross genres. It appreciates when authors try something new, or use language in interesting ways (e.g. dialect – there’s also some in the Allen-Paisant, but not as much as in the Berry). But my taste rarely aligns with theirs, such that I am unlikely to agree with its judgements. Based on my reading, I would have given the category awards to Murray, Klein and Chan and the overall award perhaps to Murray. (He recently won the inaugural Nero Book Awards’ Gold Prize instead.)

World Poetry Day stack last week

Young Writer of the Year Award

Shortlist:

- The New Life by Tom Crewe

(Past: Nero Book Award shortlist, debut fiction)

(Past: Nero Book Award shortlist, debut fiction) - Close to Home by Michael Magee (Winner: Nero Book Award, debut fiction category)

- A Flat Place by Noreen Masud (see above)

&

Bad Diaspora Poems by Momtaza Mehri

Winner: Forward Prize for Best First Collection

Nostalgia is bidirectional. Vantage point makes all the difference. Africa becomes a repository of unceasing fantasies, the sublimation of our curdled angst.

Crossing between Somalia, Italy and London and proceeding from the 1830s to the present day, this debut collection sets family history amid wider global movements. It’s peopled with nomads, colonisers, immigrants and refugees. In stanzas and prose paragraphs, wordplay and truth-telling, Mehri captures the welter of emotions for those whose identity is split between countries and complicated by conflict and migration. I particularly admired “Wink Wink,” which is presented in two columns and opens with the suspension of time before the speaker knew their father was safe after a terrorist attack. There’s super-clever enjambment in this one: “this time it happened / after evening prayer // cascade of iced tea / & sugared straws // then a line / break // hot spray of bullets & / reverb & // in less than thirty minutes we / they the land // lose twenty of our children”. Confident and sophisticated, this is a first-rate debut.

Crossing between Somalia, Italy and London and proceeding from the 1830s to the present day, this debut collection sets family history amid wider global movements. It’s peopled with nomads, colonisers, immigrants and refugees. In stanzas and prose paragraphs, wordplay and truth-telling, Mehri captures the welter of emotions for those whose identity is split between countries and complicated by conflict and migration. I particularly admired “Wink Wink,” which is presented in two columns and opens with the suspension of time before the speaker knew their father was safe after a terrorist attack. There’s super-clever enjambment in this one: “this time it happened / after evening prayer // cascade of iced tea / & sugared straws // then a line / break // hot spray of bullets & / reverb & // in less than thirty minutes we / they the land // lose twenty of our children”. Confident and sophisticated, this is a first-rate debut. ![]()

A few more favourite lines:

IX. Art is something we do when the war ends.

X. Even when no one dies on the journey, something always does.

(from “A Few Facts We Hesitantly Know to Be Somewhat True”)

You think of how casually our bodies are overruled by kin,

by blood, by heartaches disguised as homelands.

How you can count the years you have lived for yourself on one hand.

History is the hammer. You are the nail.

(from “Reciprocity is a Two-way Street”)

With thanks to Jonathan Cape (Penguin) for the free copy for review.

I hadn’t been following the Award on Instagram so totally missed the news of them bringing back a shadow panel for the first time since 2020. The four young female Bookstagrammers chose Mehri’s collection as their winner – well deserved.

Winner: The New Life by Tom Crewe

This was no surprise given that it was the Sunday Times book of the year last year (and my book of the year, to be fair). I’ve had no interest in reading the Magee. It’s a shame that a young woman of colour did not win as this year would have been a good opportunity for it. (What happened last year, seriously?!) But in that this award is supposed to be tied into the zeitgeist and honour an author on their way up in the world – as with Sally Rooney in my shadowing year – I do think the judges got it right.

Introducing the 2023 McKitterick Prize Shortlist

For the second year in a row, I was a first-round judge for the McKitterick Prize (for a first novel by a writer over 40), helping to assess the unpublished manuscripts. Perhaps lockdowns gave people time to achieve a long-held goal of writing a novel, because submissions were up by 50%. None of the manuscripts made it through to the shortlist this year or last, but one day it could happen!

The Society of Authors kindly sent me a parcel with five of the shortlisted novels, and I picked up the remaining one from the library this week. Below are synopses from Goodreads and author bios from the SoA:

The Return of Faraz Ali by Aamina Ahmad (Sceptre): “Sent back to his birthplace—Lahore’s notorious red-light district—to hush up the murder of a girl, a man finds himself in an unexpected reckoning with his past. … Profoundly intimate and propulsive, The Return of Faraz Ali is a spellbindingly assured first novel that poses a timeless question: Whom do we choose to protect, and at what price?”

The Return of Faraz Ali by Aamina Ahmad (Sceptre): “Sent back to his birthplace—Lahore’s notorious red-light district—to hush up the murder of a girl, a man finds himself in an unexpected reckoning with his past. … Profoundly intimate and propulsive, The Return of Faraz Ali is a spellbindingly assured first novel that poses a timeless question: Whom do we choose to protect, and at what price?”

Aamina Ahmad was born and raised in London, where she worked for BBC Drama and other independent television companies as a script editor. Her play The Dishonoured was produced by Kali Theatre Company in 2016. She has an MFA from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and is a recipient of a Stegner Fellowship from Stanford University, a Pushcart Prize and a Rona Jaffe Writers Award. Her short fiction has appeared in journals including One Story, the Southern Review and Ecotone. She teaches creative writing at the University of Minnesota.

When We Were Birds by Ayanna Lloyd Banwo (Hamish Hamilton): “Yejide and Darwin will meet inside the gates of Fidelis, Port Angeles’s largest and oldest cemetery, where the dead lie uneasy in their graves and a reckoning with fate beckons them both. A masterwork of lush imagination and immersive lyricism, When We Were Birds is a spellbinding novel about inheritance, loss, and love’s seismic power to heal.”

When We Were Birds by Ayanna Lloyd Banwo (Hamish Hamilton): “Yejide and Darwin will meet inside the gates of Fidelis, Port Angeles’s largest and oldest cemetery, where the dead lie uneasy in their graves and a reckoning with fate beckons them both. A masterwork of lush imagination and immersive lyricism, When We Were Birds is a spellbinding novel about inheritance, loss, and love’s seismic power to heal.”

Ayanna Lloyd Banwo is a writer from Trinidad and Tobago. She is a graduate of the University of the West Indies and holds an MA in Creative Writing from the University of East Anglia, where she is now a Creative and Critical Writing PhD candidate. Her work has been published in Moko Magazine, Small Axe and PREE, among others, and shortlisted for the Small Axe Literary Competition and the Wasafiri New Writing Prize. When We Were Birds, Ayanna’s first novel, was shortlisted for the Jhalak Prize and won the OCM Bocas Prize for Fiction. She is now working on her second novel. Ayanna lives with her husband in London.

The Gifts by Liz Hyder (Manilla Press): “October 1840. A young woman staggers alone through a forest in the English countryside as a huge pair of impossible wings rip themselves from her shoulders. In London, rumours of a “fallen angel” cause a frenzy across the city, and a surgeon desperate for fame and fortune finds himself in the grips of a dangerous obsession. … [A] spellbinding tale told through five different perspectives …, it explores science, nature and religion, enlightenment, the role of women in society and the dark danger of ambition.”

The Gifts by Liz Hyder (Manilla Press): “October 1840. A young woman staggers alone through a forest in the English countryside as a huge pair of impossible wings rip themselves from her shoulders. In London, rumours of a “fallen angel” cause a frenzy across the city, and a surgeon desperate for fame and fortune finds himself in the grips of a dangerous obsession. … [A] spellbinding tale told through five different perspectives …, it explores science, nature and religion, enlightenment, the role of women in society and the dark danger of ambition.”

Liz Hyder has been making up stories for as long she can remember. She has a BA in drama from the University of Bristol and, in early 2018, won the Bridge Award/Moniack Mhor Emerging Writer Award. Bearmouth, her debut young adult novel, won a Waterstones Children’s Book Prize, the Branford Boase Award and was chosen as the Children’s Book of the Year by The Times. Originally from London, she now lives in South Shropshire. The Gifts is her debut adult novel.

Trespasses by Louise Kennedy (Bloomsbury Publishing): “Set in Northern Ireland during the Troubles, a shattering novel about a young woman caught between allegiance to community and a dangerous passion. … As tender as it is unflinching, Trespasses is a heart-pounding, heart-rending drama of thwarted love and irreconcilable loyalties, in a place what you come from seems to count more than what you do, or whom you cherish.”

Trespasses by Louise Kennedy (Bloomsbury Publishing): “Set in Northern Ireland during the Troubles, a shattering novel about a young woman caught between allegiance to community and a dangerous passion. … As tender as it is unflinching, Trespasses is a heart-pounding, heart-rending drama of thwarted love and irreconcilable loyalties, in a place what you come from seems to count more than what you do, or whom you cherish.”

Louise Kennedy grew up a few miles from Belfast. She is the author of the Women’s Prize-shortlisted novel Trespasses, and the acclaimed short story collection The End of the World is a Cul de Sac, and is the only woman to have been shortlisted twice for the Sunday Times Audible Short Story Award (2019 and 2020). Before starting her writing career, she spent nearly thirty years working as a chef. She lives in Sligo.

The Whalebone Theatre by Joanna Quinn (Fig Tree): “One blustery night in 1928, a whale washes up on the shores of the English Channel. By law, it belongs to the King, but twelve-year-old orphan Cristabel Seagrave has other plans. She and the rest of the household … build a theatre from the beast’s skeletal rib cage. … As Cristabel grows into a headstrong young woman, World War II rears its head.”

The Whalebone Theatre by Joanna Quinn (Fig Tree): “One blustery night in 1928, a whale washes up on the shores of the English Channel. By law, it belongs to the King, but twelve-year-old orphan Cristabel Seagrave has other plans. She and the rest of the household … build a theatre from the beast’s skeletal rib cage. … As Cristabel grows into a headstrong young woman, World War II rears its head.”

Joanna Quinn was born in London and grew up in the southwest of England, where her bestselling debut novel, The Whalebone Theatre, is set. Joanna has worked in journalism and the charity sector. She is also a short story writer, published by The White Review and Comma Press, among others. She lives in a village near the sea in Dorset.

Other Names for Love by Taymour Soomro (Harvill Secker): “A seductive coming-of-age story about queer desire, Other Names for Love is a charged, hypnotic debut novel about a boy’s life-changing summer in rural Pakistan: a story of fathers, sons, and the consequences of desire. … Decades later, Fahad is living abroad when he receives a call from his mother summoning him home. … [A] tale of masculinity, inheritance, and desire set against the backdrop of a country’s violent history, told with uncommon urgency and beauty.”

Other Names for Love by Taymour Soomro (Harvill Secker): “A seductive coming-of-age story about queer desire, Other Names for Love is a charged, hypnotic debut novel about a boy’s life-changing summer in rural Pakistan: a story of fathers, sons, and the consequences of desire. … Decades later, Fahad is living abroad when he receives a call from his mother summoning him home. … [A] tale of masculinity, inheritance, and desire set against the backdrop of a country’s violent history, told with uncommon urgency and beauty.”

Taymour Soomro is the author of Other Names for Love and co-editor of Letters to a Writer of Colour. His writing has been published in the New Yorker, the New York Times and elsewhere. He is the recipient of fellowships from the Wisconsin Institute for Creative Writing, Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference and the Sozopol Fiction Seminars. He has degrees from Cambridge University and Stanford Law School and a PhD in creative writing from the University of East Anglia. He currently teaches on the MFA program at Bennington College.

Fellow judge Selma Dabbagh summarises the shortlist thus: “Family estates in rural Pakistan (Other Names for Love) and England (The Whalebone Theatre) fall into decline reflecting the hubris and short-sightedness of their owners[;] in The Return of Faraz Ali, it is the decaying grandeur of the courtesans of Lahore that is lovingly depicted. Whereas in both The Gifts and When We Were Birds, the otherworldly brings new possibilities to the tawdry and impoverished as mystical wings fly over the slums of Victorian London and the graveyards of Trinidad.”

I was already interested in reading a couple of these novels, and was pleased to discover a few new-to-me titles. As it’s also shortlisted for the Women’s Prize (which will be awarded on Wednesday), it seems to make sense to start with Trespasses, and I’m also particularly keen on The Gifts, which sounds like a great holiday read and right up my street, so I’m packing it for our trip to Scotland later this month. One or more of the others might end up on my 20 Books of Summer list. I’ll be sure to follow up with reviews of any I manage to read this summer.

The winner and runner-up will be announced at the SoA Awards ceremony in London on 29 June. I’ll be away at the time but will hope to watch part of the livestream. For more on all of the SoA Awards, see the press release on their website.

See any nominees you’ve read? Who would you like to see win?

Christmas is approaching, and with it a blizzard, but first comes Will Stanton’s birthday on Midwinter Day. A gathering of rooks and a farmer’s ominous pronouncement (“The Walker is abroad. And this night will be bad, and tomorrow will be beyond imagining”) and gift of an iron talisman are signals that his eleventh birthday will be different than those that came before. While his large family gets on with their preparations for a traditional English Christmas, they have no idea Will is being ferried by a white horse to a magic hall, where he is let in on the secret of his membership in an ancient alliance meant to combat the forces of darkness. Merriman will be his guide as he gathers Signs and follows the Old Ones’ Ways.

Christmas is approaching, and with it a blizzard, but first comes Will Stanton’s birthday on Midwinter Day. A gathering of rooks and a farmer’s ominous pronouncement (“The Walker is abroad. And this night will be bad, and tomorrow will be beyond imagining”) and gift of an iron talisman are signals that his eleventh birthday will be different than those that came before. While his large family gets on with their preparations for a traditional English Christmas, they have no idea Will is being ferried by a white horse to a magic hall, where he is let in on the secret of his membership in an ancient alliance meant to combat the forces of darkness. Merriman will be his guide as he gathers Signs and follows the Old Ones’ Ways.