#MARM2024: Life before Man and Interlunar by Margaret Atwood

Hard to believe, but it’s my seventh year participating in the annual Margaret Atwood Reading Month (#MARM) hosted by indomitable Canadian blogger Marcie of Buried in Print. In previous years, I’ve read Surfacing and The Edible Woman, The Robber Bride and Moral Disorder, Wilderness Tips, The Door, and Bodily Harm and Stone Mattress; and reread The Blind Assassin. I’m wishing a happy belated birthday to Atwood, who turned 85 earlier this month. Novembers are my excuse to catch up on her extensive back catalogue. In recent years, I’ve scoured the university library holdings to find works by her that I often had never heard of, as was the case with this early novel and mid-career poetry collection.

Life before Man (1979)

Atwood’s fourth novel is from three rotating third-person POVs: Toronto museum curator Elizabeth, her toy-making husband Nate, and Lesje (pronounced “Lashia,” according to a note at the front), Elizabeth’s paleontologist colleague. The dated chapters span nearly two years, October 1976 to August 1978; often we visit with two or three protagonists on the same day. Elizabeth and Nate, parents to two daughters, have each had a string of lovers. Elizabeth’s most recent, Chris, has died by suicide. Nate disposes of his latest mistress, Martha, and replaces her with Lesje, who is initially confused by his interest in her. She’s more attracted to rocks and dinosaurs than to people, in a way that could be interpreted as consistent with neurodivergence.

Atwood’s fourth novel is from three rotating third-person POVs: Toronto museum curator Elizabeth, her toy-making husband Nate, and Lesje (pronounced “Lashia,” according to a note at the front), Elizabeth’s paleontologist colleague. The dated chapters span nearly two years, October 1976 to August 1978; often we visit with two or three protagonists on the same day. Elizabeth and Nate, parents to two daughters, have each had a string of lovers. Elizabeth’s most recent, Chris, has died by suicide. Nate disposes of his latest mistress, Martha, and replaces her with Lesje, who is initially confused by his interest in her. She’s more attracted to rocks and dinosaurs than to people, in a way that could be interpreted as consistent with neurodivergence.

It was neat to follow along seasonally with Halloween and Remembrance Day and so on, and see the Quebec independence movement simmering away in the background. To start with, I was engrossed in the characters’ perspectives and taken with Atwood’s witty descriptions and dialogue: “[Nate]’s heard Unitarianism called a featherbed for falling Christians” and (Lesje:) “Elizabeth needs support like a nun needs tits.” My favourite passage encapsulates a previous relationship of Lesje’s perfectly, in just the sort of no-nonsense language she would use:

The geologist had been fine; they could compromise on rock strata. They went on hikes with their little picks and kits, and chipped samples off cliffs; then they ate jelly sandwiches and copulated in a friendly way behind clumps of goldenrod and thistles. She found this pleasurable but not extremely so. She still has a collection of rock chips left over from this relationship; looking at it does not fill her with bitterness. He was a nice boy but she wasn’t in love with him.

Elizabeth’s formidable Auntie Muriel is a terrific secondary presence. But this really is just a novel about (repeated) adultery and its aftermath. The first line has Elizabeth thinking “I don’t know how I should live,” and after some complications, all three characters are trapped in a similar stasis by the end. By the halfway point I’d mostly lost interest and started skimming. The grief motif and museum setting weren’t the draws I’d expected them to be. Lesje is a promising character but, disappointingly, gets snared in clichéd circumstances. No doubt that is part of the point; “life before man” would have been better for her. (University library) ![]()

This prophetic passage from Life before Man leads nicely into the themes of Interlunar:

The real question is: Does [Lesje] care whether the human race survives or not? She doesn’t know. The dinosaurs didn’t survive and it wasn’t the end of the world. In her bleaker moments, … she feels the human race has it coming. Nature will think up something else. Or not, as the case may be.

The posthuman prospect is echoed in Interlunar in the lines: “Which is the sound / the earth will make for itself / without us. A stone echoing a stone.”

Interlunar (1984)

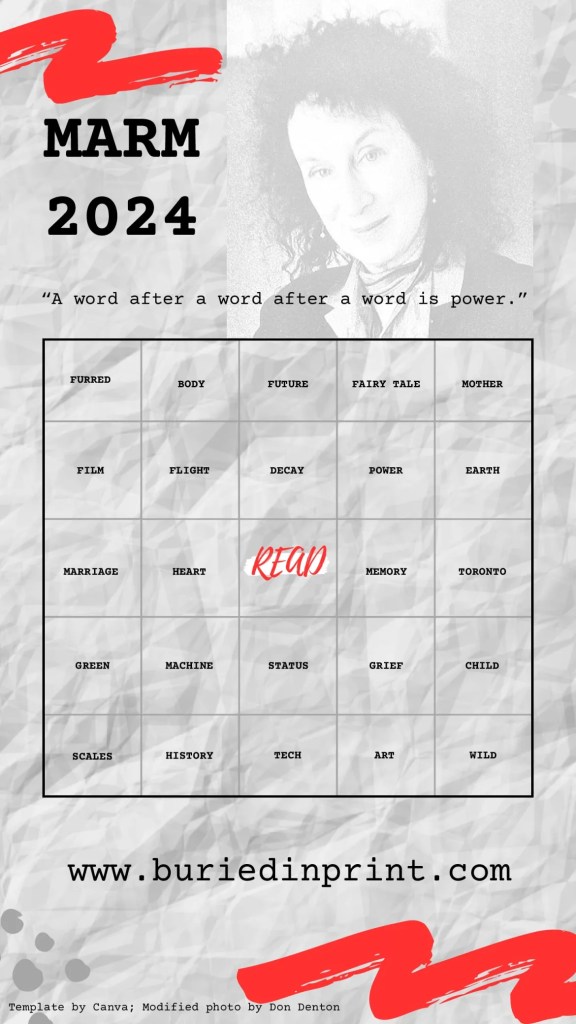

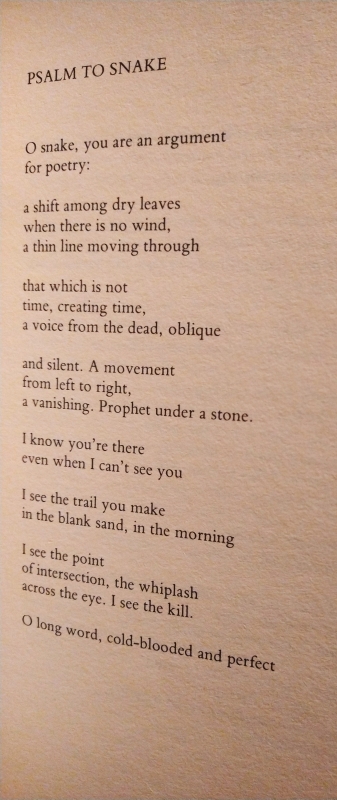

Some familiar Atwood elements in this volume, including death, mythology, nature, and stays at a lake house; you’ll even recognize a couple of her other works in poem titles “The Robber Bridegroom” and “The Burned House.” The opening set of “Snake Poems” got me the “green” and “scales” squares on Marcie’s Bingo card (in addition to various other scattered ones, I’m gonna say I’ve filled the whole right-hand column thanks to these two books).

This one brilliantly likens the creature to the sinuous ways of language:

“A Holiday” imagines a mother–daughter camping vacation presaging a postapocalyptic struggle for survival: “This could be where we / end up, learning the minimal / with maybe no tree, no rain, / no shelter, no roast carcasses / of animals to renew us … So far we do it / for fun.” As in her later collection The Door, portals and thresholds are of key importance. “Doorway” intones, “November is the month of entrance, / month of descent. Which has passed easily, / which has been lenient with me this year. / Nobody’s blood on the floor.” There are menace and melancholy here. But as “Orpheus (2)” suggests at its close, art can be an ongoing act of resistance: “To sing is either praise / or defiance. Praise is defiance.” I do recommend Atwood’s poetry if you haven’t tried it before, even if you’re not typically a poetry reader. Her poems are concrete and forceful, driven by imagery and voice; not as abstract as you might fear. Alas, I wasn’t sent a review copy of her collected poems, Paper Boat, as I’d hoped, but I will continue to enjoy encountering them piecemeal. (University library)

“A Holiday” imagines a mother–daughter camping vacation presaging a postapocalyptic struggle for survival: “This could be where we / end up, learning the minimal / with maybe no tree, no rain, / no shelter, no roast carcasses / of animals to renew us … So far we do it / for fun.” As in her later collection The Door, portals and thresholds are of key importance. “Doorway” intones, “November is the month of entrance, / month of descent. Which has passed easily, / which has been lenient with me this year. / Nobody’s blood on the floor.” There are menace and melancholy here. But as “Orpheus (2)” suggests at its close, art can be an ongoing act of resistance: “To sing is either praise / or defiance. Praise is defiance.” I do recommend Atwood’s poetry if you haven’t tried it before, even if you’re not typically a poetry reader. Her poems are concrete and forceful, driven by imagery and voice; not as abstract as you might fear. Alas, I wasn’t sent a review copy of her collected poems, Paper Boat, as I’d hoped, but I will continue to enjoy encountering them piecemeal. (University library) ![]()

Recent BookBrowse & Shiny New Books Reviews, and Book Club Ado

Excerpts from and links to some of my recent online writing for other places:

BookBrowse

Three O’Clock in the Morning by Gianrico Carofiglio

The quotation that gives Carofiglio’s tender novel its title is from F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Crack-Up: “In a real dark night of the soul it is always three o’clock in the morning.” It lends an appropriate sense of time suspended, of earnest seeking and extreme circumstances: The main action of the book takes place over just a few days in June of 1983, when Italian teenager Antonio and his father are stranded in Marseilles while there for Antonio to be seen by an epilepsy specialist. The gift of this time outside of time allows them to get to know each other better, such that the memory of the trip will be precious to Antonio even decades later. I appreciated how the limited setting heightened this short novel’s emotions. Carofiglio invites readers to peer between the leisurely progression of events to see the bond that is being formed. (See my full review at BookBrowse. See also my related article on HarperVia, a new publishing imprint for international literature.)

The quotation that gives Carofiglio’s tender novel its title is from F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Crack-Up: “In a real dark night of the soul it is always three o’clock in the morning.” It lends an appropriate sense of time suspended, of earnest seeking and extreme circumstances: The main action of the book takes place over just a few days in June of 1983, when Italian teenager Antonio and his father are stranded in Marseilles while there for Antonio to be seen by an epilepsy specialist. The gift of this time outside of time allows them to get to know each other better, such that the memory of the trip will be precious to Antonio even decades later. I appreciated how the limited setting heightened this short novel’s emotions. Carofiglio invites readers to peer between the leisurely progression of events to see the bond that is being formed. (See my full review at BookBrowse. See also my related article on HarperVia, a new publishing imprint for international literature.)

The Dictionary of Lost Words by Pip Williams

Inspired by the composition of the Oxford English Dictionary, this Australian debut novel explores the lives of the women on its fringes through the words that were omitted. The suffrage movement and World War I loom large as the storyline enters the 1910s. I most appreciated the relationships Esme has with the various women in her life. The main action spans the 40 years of the original composition of the OED. That scope means there is a lot of skipping forward in time. Especially in the first half, I longed for the narrative to slow down so I could spend more time with this character. Despite the first-person narration, I never felt I knew Esme very well. Women’s bonds and women’s words are strong themes in this forthrightly feminist novel that, despite its flaws, would make a great book club selection. (See my full review at BookBrowse. See also my reading list of books about dictionaries and lost words.)

Inspired by the composition of the Oxford English Dictionary, this Australian debut novel explores the lives of the women on its fringes through the words that were omitted. The suffrage movement and World War I loom large as the storyline enters the 1910s. I most appreciated the relationships Esme has with the various women in her life. The main action spans the 40 years of the original composition of the OED. That scope means there is a lot of skipping forward in time. Especially in the first half, I longed for the narrative to slow down so I could spend more time with this character. Despite the first-person narration, I never felt I knew Esme very well. Women’s bonds and women’s words are strong themes in this forthrightly feminist novel that, despite its flaws, would make a great book club selection. (See my full review at BookBrowse. See also my reading list of books about dictionaries and lost words.)

Shiny New Books

Notes from Deep Time: The Hidden Stories of the Earth Beneath Our Feet by Helen Gordon

To assess the place of humanity, we can look back to prehistory, but also forward to envision the “deep future.” (It was only in a late chapter on nuclear waste disposal sites and warning messages to the future that I found too much direct overlap with Footprints by David Farrier.) This engagingly blends both tactics, surveying the fields of geology and palaeontology and pondering the future traces of the Anthropocene. I most enjoyed the middle chapters, in which science meets wildlife and cultural studies. For instance, a chapter on ammonites leads into a profile of Mary Anning and the history of both fossil hunting and women in STEM careers. The prose is well pitched to the layman’s level. Interviews, travels, and snapshots from her own life generally keep the material from becoming too dry. An invigorating interdisciplinary tour. (See my full review at Shiny New Books.)

To assess the place of humanity, we can look back to prehistory, but also forward to envision the “deep future.” (It was only in a late chapter on nuclear waste disposal sites and warning messages to the future that I found too much direct overlap with Footprints by David Farrier.) This engagingly blends both tactics, surveying the fields of geology and palaeontology and pondering the future traces of the Anthropocene. I most enjoyed the middle chapters, in which science meets wildlife and cultural studies. For instance, a chapter on ammonites leads into a profile of Mary Anning and the history of both fossil hunting and women in STEM careers. The prose is well pitched to the layman’s level. Interviews, travels, and snapshots from her own life generally keep the material from becoming too dry. An invigorating interdisciplinary tour. (See my full review at Shiny New Books.)

My book club has been meeting via Zoom since April 2020. This is a common state of affairs for book clubs around the world. Especially since we have 12 members (if everyone attends, which is rare), we haven’t been able to contemplate meeting in person as of yet. However, a subset of us meet midway between the monthly reads to discuss women’s classics like Marge Piercy’s Woman on the Edge of Time. For next week’s meeting on Mrs. Dalloway, we are going to attempt a six-person get-together in one member’s house.

Anyway, a neat thing we did last month was a Zoom chat with the author: a BBC correspondent who happens to be the brother of one of our members. If you’re a news junkie in the UK, you may know the name Jon Sopel, though since I don’t have a telly or ever listen to radio, I hadn’t encountered him until this “in-person” meet-up. He has been the BBC’s North America Editor since 2014.

Anyway, a neat thing we did last month was a Zoom chat with the author: a BBC correspondent who happens to be the brother of one of our members. If you’re a news junkie in the UK, you may know the name Jon Sopel, though since I don’t have a telly or ever listen to radio, I hadn’t encountered him until this “in-person” meet-up. He has been the BBC’s North America Editor since 2014.

UnPresidented is the third book he wrote over the course of the Trump presidency. It started off as a diary of the 2020 election campaign, beginning in July 2019, but of course soon morphed into something slightly different: a chronicle of life in D.C. and London during Covid-19 and a record of the Trump mishandling of the pandemic. But as well as a farcical election process and a public health crisis, 2020’s perfect storm also included economic collapse and social upheaval – thanks to the murder of George Floyd and the subsequent Black Lives Matter protests worldwide plus isolated rioting.

UnPresidented served as a good reminder for me of the timeline of events and the full catalogue of outrages committed by Trump and his cronies. You just have to shake your head over the litany of ridiculous things he said and did, and got away with – any one of which might have sunk another president or candidate. The style is breezy and off-the-cuff, so the book reads quickly. There’s a good balance between world events and personal ones, with his family split across the UK and Australia. I appreciated the insight into differences from the British system. I thought it would be depressing reading back through the events of 2020, but for the most part the knowledge that everything turned out “right” allowed me to see the humour in it. Still, I found it excruciating reading about the four days following the election.

Sopel kindly gave us an hour of his time one Wednesday evening before he had to go on air and answered our questions about Biden, Harris, journalistic ethics, and more. He was charming and eloquent, as befits his profession.

Would any of these books interest you?

A Hundred Million Years and a Day by Jean-Baptiste Andrea

Stanislas Armengol remembers finding his first trilobite at the age of six. His fossils and his dog were his best friends during a lonely childhood dominated by a violent father nicknamed “The Commander.” Now, in the summer of 1954, Stan is a 52-year-old paleontologist embarking on the greatest project of his career. He sold his apartment in Paris to finance this expedition to the French/Italian Alps in search of a “dragon” (perhaps a diplodocus) said to be buried in a glacier between three mountain peaks.

Stanislas Armengol remembers finding his first trilobite at the age of six. His fossils and his dog were his best friends during a lonely childhood dominated by a violent father nicknamed “The Commander.” Now, in the summer of 1954, Stan is a 52-year-old paleontologist embarking on the greatest project of his career. He sold his apartment in Paris to finance this expedition to the French/Italian Alps in search of a “dragon” (perhaps a diplodocus) said to be buried in a glacier between three mountain peaks.

“A scientist does not unquestioningly swallow a tall tale without demanding some proof, some concrete detail,” Stan insists. “Doubt is our religion.” But he’s seen a promising bone fragment from the region, and his excitement soon outweighs his uncertainty. This is his chance to finally make a name for himself. Arriving from Turin to join Stan are his friend and former assistant Umberto, and Umberto’s assistant, Peter. Gio, a local, will be their guide. It’s a tough climb requiring ropes and harnesses. As autumn approaches, and then winter, the hunt for the fossil becomes more frantic. The others are prepared to come back next year if it’s no longer sensible to continue, but Stan has staked everything on the venture and won’t quit.

Stan’s obsession puts him in touch with deep time – he’s “someone whose profession forces him to think in terms of millions of years” – but his thoughts keep returning to moments of joy or distress from his childhood. Although she died when he was nine years old, his beloved mother still looms large in his memory. Even as the realities of cold and hunger intensify, his past comes to seem more vivid than his present.

This French bestseller was shortlisted for the Grand Prix de l’Académie Française last year. Sam Taylor’s translation is flawless, as always (I only noted one tiny phrase that felt wrong for the time period – “honestly, what a brat” – though for all I know it’s off in the original, too). However, I found the novella uncannily similar to Snow, Dog, Foot by Claudio Morandini, which is about a hermit in the Italian Alps whose mental illness is exacerbated by snowy solitude. I found Morandini’s witty, macabre story more memorable. Although A Hundred Million Years and a Day is well constructed, there’s something austere about it that meant my admiration never quite moved into fondness.

My rating:

A Hundred Million Years and a Day will be published in the UK tomorrow, the 11th. My thanks to Gallic Books for the free copy for review.

I was delighted to be invited to participate in the blog tour. See below for details of where other reviews and features have appeared or will be appearing soon.