#ReadIndies Nonfiction Catch-Up: Ansell, Farrier, Febos, Hoffman, Orlean and Stacey

These are all 2025 releases; for some, it’s approaching a year since I was sent a review copy or read the book. Silly me. At last, I’ve caught up. Reading Indies month, hosted by Kaggsy in memory of her late co-host Lizzy Siddal, is the perfect time to feature books from five independent publishers. I have four works that might broadly be classed as nature writing – though their topics range from birdsong and technology to living in Greece and rewilding a plot in northern Spain – and explorations of celibacy and the writer’s profession.

The Edge of Silence: In Search of the Disappearing Sounds of Nature by Neil Ansell

Ansell draws parallels between his advancing hearing loss and the biodiversity crisis. He puts together a wish list of species – mostly seabirds (divers, grebes), but also inland birds (nightjars) and a couple of non-avian representatives (otters) – that he wants to hear and sets off on public transport adventures to find them. “I must find beauty where I can, and while I still can,” he vows. From his home on the western coast of Scotland near the Highlands, this involves trains or buses that never align with the ferry timetables. Furthest afield for him are two nature reserves in northern England where his mission is to hear bitterns “booming” and natterjack toads croaking at night. There are also mountain excursions to locate ptarmigan, greenshank, and black grouse. His island quarry includes Manx shearwaters (Rum), corncrakes (Coll), puffins (Sanday), and storm petrels (Shetland).

Ansell draws parallels between his advancing hearing loss and the biodiversity crisis. He puts together a wish list of species – mostly seabirds (divers, grebes), but also inland birds (nightjars) and a couple of non-avian representatives (otters) – that he wants to hear and sets off on public transport adventures to find them. “I must find beauty where I can, and while I still can,” he vows. From his home on the western coast of Scotland near the Highlands, this involves trains or buses that never align with the ferry timetables. Furthest afield for him are two nature reserves in northern England where his mission is to hear bitterns “booming” and natterjack toads croaking at night. There are also mountain excursions to locate ptarmigan, greenshank, and black grouse. His island quarry includes Manx shearwaters (Rum), corncrakes (Coll), puffins (Sanday), and storm petrels (Shetland).

Camping in a tent means cold nights, interrupted sleep, and clouds of midges, but it’s all worth it to have unrepeatable wildlife experiences. He has a very high hit rate for (seeing and) hearing what he intends to, even when they’re just on the verge of what he can decipher with his hearing aids. On the rare occasions when he misses out, he consoles himself with earlier encounters. “I shall settle for the memory, for it feels unimprovable, like a spell that I do not want to break.” I’ve read all of Ansell’s nature memoirs and consider him one of the UK’s top writers on the natural world. His accounts of his low-carbon travels are entertaining, and the tug-of-war between resisting and coming to terms with his disability is heartening. “I have spent this year in defiance of a relentless, unstoppable countdown,” he reflects. What makes this book more universal than niche is the deadline: we and all of these creatures face extinction. Whether it’s sooner or later depends on how we act to address the environmental polycrisis.

With thanks to Birlinn for the free copy for review.

Nature’s Genius: Evolution’s Lessons for a Changing Planet by David Farrier

Farrier’s Footprints, which tells the story of the human impact on the Earth, was one of my favourite books of 2020. This contains a similar blend of history, science, and literary points of reference (Farrier is a professor of literature and the environment at the University of Edinburgh), with past changes offering a template for how the future might look different. “We are forcing nature to reimagine itself, and to avert calamity we need to do the same,” he writes. Cliff swallows have evolved blunter wings to better evade cars; captive breeding led foxes to develop the domesticated traits of pet dogs.

Farrier’s Footprints, which tells the story of the human impact on the Earth, was one of my favourite books of 2020. This contains a similar blend of history, science, and literary points of reference (Farrier is a professor of literature and the environment at the University of Edinburgh), with past changes offering a template for how the future might look different. “We are forcing nature to reimagine itself, and to avert calamity we need to do the same,” he writes. Cliff swallows have evolved blunter wings to better evade cars; captive breeding led foxes to develop the domesticated traits of pet dogs.

It’s not just other species that experience current evolution. Thanks to food abundance and a sedentary lifestyle, humans show a “consumer phenotype,” which superseded the Palaeolithic (95% of human history) and tends toward earlier puberty, autoimmune diseases, and obesity. Farrier also looks at notions of intelligence, language, and time in nature. Sustainable cities will have to cleverly reuse materials. For instance, The Waste House in Brighton is 90% rubbish. (This I have to see!)

There are many interesting nuggets here, and statements that are difficult to argue with, but I struggled to find an overall thread. Cool to see my husband’s old housemate mentioned, though. (Duncan Geere, for collaborating on a hybrid science–art project turning climate data into techno music.)

With thanks to Canongate for the free copy for review.

The Dry Season: Finding Pleasure in a Year without Sex by Melissa Febos

Febos considers but rejects the term “sex addiction” for the years in which she had compulsive casual sex (with “the Last Man,” yes, but mostly with women). Since her early teen years, she’d never not been tied to someone. Brief liaisons alternated with long-term relationships: three years with “the Best Ex”; two years that were so emotionally tumultuous that she refers to the woman as “the Maelstrom.” It was the implosion of the latter affair that led to Febos deciding to experiment with celibacy, first for three months, then for a whole year. “I felt feral and sad and couldn’t explain it, but I knew that something had to change.”

The quest involved some research into celibate movements in history, but was largely an internal investigation of her past and psyche. Febos found that she was less attuned to the male gaze. Having worn high heels almost daily for 20 years, she discovered she’s more of a trainers person. Although she was still tempted to flirt with attractive women, e.g. on an airplane, she consciously resisted the impulse to spin random meetings into one-night stands. (A therapist had stopped her short with the blunt observation, “you use people.”) With a new focus on the life of the mind, she insists, “My life was empty of lovers and more full than it had ever been.” (This reminded me of Audre Lorde’s writing on the erotic.) As Silvana Panciera, an Italian scholar on the beguines (a secular nun-like sisterhood), told her: “When you don’t belong to anyone, you belong to everyone. You feel able to love without limits.”

The quest involved some research into celibate movements in history, but was largely an internal investigation of her past and psyche. Febos found that she was less attuned to the male gaze. Having worn high heels almost daily for 20 years, she discovered she’s more of a trainers person. Although she was still tempted to flirt with attractive women, e.g. on an airplane, she consciously resisted the impulse to spin random meetings into one-night stands. (A therapist had stopped her short with the blunt observation, “you use people.”) With a new focus on the life of the mind, she insists, “My life was empty of lovers and more full than it had ever been.” (This reminded me of Audre Lorde’s writing on the erotic.) As Silvana Panciera, an Italian scholar on the beguines (a secular nun-like sisterhood), told her: “When you don’t belong to anyone, you belong to everyone. You feel able to love without limits.”

Intriguing that this is all a retrospective, reflecting on her thirties; Febos is now in her mid-forties and married to a woman (poet Donika Kelly). Clearly she felt that it was an important enough year – with landmark epiphanies that changed her and have the potential to help others – to form the basis for a book. For me, she didn’t have much new to offer about celibacy, though it was interesting to read about the topic from an areligious perspective. But I admire the depth of her self-knowledge, and particularly her ability to recreate her mindset at different times. This is another one, like her Girlhood, to keep on the shelf as a model.

With thanks to Canongate for the free copy for review.

Lifelines: Searching for Home in the Mountains of Greece by Julian Hoffman

Hoffman’s Irreplaceable was my nonfiction book of 2019. Whereas that was a work with a global environmentalist perspective, Lifelines is more personal in scope. It tracks the author’s unexpected route from Canada via the UK to Prespa, a remote area of northern Greece that’s at the crossroads with Albania and North Macedonia. He and his wife, Julia, encountered Prespa in a book and, longing for respite from the breakneck pace of life in London, moved there in 2000. “Like the rivers that spill into these shared lakes, lifelines rarely flow straight. Instead, they contain bends, meanders and loops; they hold, at times, turns of extraordinary surprise.” Birdwatching, which Hoffman suggests is as “a way of cultivating attention,” had been their gateway into a love for nature developed over the next quarter-century and more, and in Greece they delighted in seeing great white and Dalmatian pelicans (which feature on the splendid U.S. cover. It would be lovely to have an illustrated edition of this.)

Hoffman’s Irreplaceable was my nonfiction book of 2019. Whereas that was a work with a global environmentalist perspective, Lifelines is more personal in scope. It tracks the author’s unexpected route from Canada via the UK to Prespa, a remote area of northern Greece that’s at the crossroads with Albania and North Macedonia. He and his wife, Julia, encountered Prespa in a book and, longing for respite from the breakneck pace of life in London, moved there in 2000. “Like the rivers that spill into these shared lakes, lifelines rarely flow straight. Instead, they contain bends, meanders and loops; they hold, at times, turns of extraordinary surprise.” Birdwatching, which Hoffman suggests is as “a way of cultivating attention,” had been their gateway into a love for nature developed over the next quarter-century and more, and in Greece they delighted in seeing great white and Dalmatian pelicans (which feature on the splendid U.S. cover. It would be lovely to have an illustrated edition of this.)

One strand of this warm and fluent memoir is about making a home in Greece: buying and renovating a semi-derelict property, experiencing xenophobia and hospitality from different quarters, and finding a sense of belonging. They’re happy to share their home with nesting wrens, who recur across the book and connect to the tagline of “a story of shelter shared.” In probing the history of his adopted country, Hoffman comes to realise the false, arbitrary nature of borders – wildlife such as brown bears and wolves pay these no heed. Everything is connected and questions of justice are always intersectional. The Covid pandemic and avian influenza (which devastated the region’s pelicans) are setbacks that Hoffman addresses honestly. But the lingering message is a valuable one of bridging divisions and learning how to live in harmony with other people – and with other species.

One strand of this warm and fluent memoir is about making a home in Greece: buying and renovating a semi-derelict property, experiencing xenophobia and hospitality from different quarters, and finding a sense of belonging. They’re happy to share their home with nesting wrens, who recur across the book and connect to the tagline of “a story of shelter shared.” In probing the history of his adopted country, Hoffman comes to realise the false, arbitrary nature of borders – wildlife such as brown bears and wolves pay these no heed. Everything is connected and questions of justice are always intersectional. The Covid pandemic and avian influenza (which devastated the region’s pelicans) are setbacks that Hoffman addresses honestly. But the lingering message is a valuable one of bridging divisions and learning how to live in harmony with other people – and with other species.

With thanks to Elliott & Thompson for the free copy for review.

Joyride by Susan Orlean

As a long-time staff writer for The New Yorker, Orlean has had the good fortune to be able to follow her curiosity wherever it leads, chasing the subjects that interest her and drawing readers in with her infectious enthusiasm. She grew up in suburban Ohio, attended college in Michigan, and lived in Portland, Oregon and Boston before moving to New York City. Her trajectory was from local and alternative papers to the most enviable of national magazines: Esquire, Rolling Stone and Vogue. Orlean gives behind-the-scenes information on lots of her early stories, some of which are reprinted in an appendix. “If you’re truly open, it’s easy to fall in love with your subject,” she writes; maintaining objectivity could be difficult, as when she profiled an Indian spiritual leader with a cult following; and fended off an interviewee’s attachment when she went on the road with a Black gospel choir.

Her personal life takes a backseat to her career, though she is frank about the breakdown of her first marriage, her second chance at love and late motherhood, and a surprise bout with lung cancer. The chronological approach proceeds book by book, delving into her inspirations, research process and publication journeys. Her first book was about Saturday night as experienced across America. It was a more innocent time, when subjects were more trusting. Orlean and her second husband had farms in the Hudson Valley of New York and in greater Los Angeles, and she ended up writing a lot about animals, with books on Rin Tin Tin and one collecting her animal pieces. There was also, of course, The Library Book, about the wild history of the main Los Angeles public library. But it’s her The Orchid Thief – and the movie (not) based on it, Adaptation – that’s among my favourites, so the long section on that was the biggest thrill for me. There are also black-and-white images scattered through.

Her personal life takes a backseat to her career, though she is frank about the breakdown of her first marriage, her second chance at love and late motherhood, and a surprise bout with lung cancer. The chronological approach proceeds book by book, delving into her inspirations, research process and publication journeys. Her first book was about Saturday night as experienced across America. It was a more innocent time, when subjects were more trusting. Orlean and her second husband had farms in the Hudson Valley of New York and in greater Los Angeles, and she ended up writing a lot about animals, with books on Rin Tin Tin and one collecting her animal pieces. There was also, of course, The Library Book, about the wild history of the main Los Angeles public library. But it’s her The Orchid Thief – and the movie (not) based on it, Adaptation – that’s among my favourites, so the long section on that was the biggest thrill for me. There are also black-and-white images scattered through.

It was slightly unfortunate that I read this at the same time as Book of Lives – who could compete with Margaret Atwood? – but it is, yes, a joy to read about Orlean’s writing life. She’s full of enthusiasm and good sense, depicting the vocation as part toil and part magic:

“I find superhuman self-confidence when I’m working on a story. The bashfulness and vulnerability that I might otherwise experience in a new setting melt away, and my desire to connect, to observe, to understand, powers me through.”

“I like to do a gut check any time I dismiss or deplore something I don’t know anything about. That feels like reason enough to learn about it.”

“anything at all is worth writing about if you care about it and it makes you curious and makes you want to holler about it to other people”

With thanks to Atlantic Books for the free copy for review.

No Paradise with Wolves: A Journey of Rewilding and Resilience by Katie Stacey

I had the good fortune to visit Wild Finca, Luke Massey and Katie Stacey’s rewilding site in Asturias, while on holiday in northern Spain in May 2022, and was intrigued to learn more about their strategy and experiences. This detailed account of the first four years begins with their search for a property in 2018 and traces the steps of their “agriwilding” of a derelict farm: creating a vegetable garden and tending to fruit trees, but also digging ponds, training up hedgerows, and setting up rotational grazing. Their every decision went against the grain. Others focussed on one crop or type of livestock while they encouraged unruly variety, keeping chickens, ducks, goats, horses and sheep. Their neighbours removed brush in the name of tidiness; they left the bramble and gorse to welcome in migrant birds. New species turned up all the time, from butterflies and newts to owls and a golden fox.

Luke is a wildlife guide and photographer. He and Katie are conservation storytellers, trying to get people to think differently about land management. The title is a Spanish farmers’ and hunters’ slogan about the Iberian wolf. Fear of wolves runs deep in the region. Initially, filming wolves was one of the couple’s major goals, but they had to step back because staking out the animals’ haunts felt risky; better to let them alone and not attract the wrong attention. (Wolf hunting was banned across Spain in 2021.) There’s a parallel to be found here between seeing wolves as a threat and the mild xenophobia the couple experienced. Other challenges included incompetent house-sitters, off-lead dogs killing livestock, the pandemic, wildfires, and hunters passing through weekly (as in France – as we discovered at Le Moulin de Pensol in 2024 – hunters have the right to traverse private land in Spain).

Luke and Katie hope to model new ways of living harmoniously with nature – even bears and wolves, which haven’t made it to their land yet, but might in the future – for the region’s traditional farmers. They’re approaching self-sufficiency – for fruit and vegetables, anyway – and raising their sons, Roan and Albus, to love the wild. We had a great day at Wild Finca: a long tour and badger-watching vigil (no luck that time) led by Luke; nettle lemonade and sponge cake with strawberries served by Katie and the boys. I was clear how much hard work has gone into the land and the low-impact buildings on it. With the exception of some Workaway volunteers, they’ve done it all themselves.

Katie Stacey’s storytelling is effortless and conversational, making this impassioned memoir a pleasure to read. It chimed perfectly with Hoffman’s writing (above) about the fear of bears and wolves, and reparation policies for farmers, in Europe. I’d love to see the book get a bigger-budget release complete with illustrations, a less misleading title, the thorough line editing it deserves, and more developmental work to enhance the literary technique – as in the beautiful final chapter, a present-tense recreation of a typical walk along The Loop. All this would help to get the message the wider reach that authors like Isabella Tree have found. “I want to be remembered for the wild spaces I leave behind,” Katie writes in the book’s final pages. “I want to be remembered as someone who inspired people to seek a deeper connection to nature.” You can’t help but be impressed by how much of a difference two people seeking to live differently have achieved in just a handful of years. We can all rewild the spaces available to us (see also Kate Bradbury’s One Garden against the World), too.

With thanks to Earth Books (Collective Ink) for the free copy for review.

Which of these do you fancy reading?

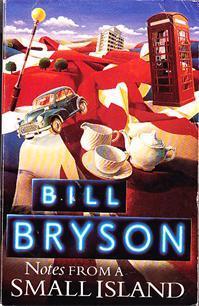

Bill Bryson’s Notes from a Small Island: Reread and Stage Production

Bill Bryson, an American author of humorous travel and popular history or science books, is considered a national treasure in his adopted Great Britain. He is a particular favourite of my husband and in-laws, who got me into his work back in the early to mid-2000s. As I, too, was falling in love with the country, I found much to relate to in his travel-based memoirs of expatriate life and temporary returns to the USA. Sometimes it takes an outsider’s perspective to see things clearly.

When we heard that Notes from a Small Island (1995), his account of a valedictory tour around Britain before returning to live in the States for the first time in 20 years, had been adapted into a play by Tim Whitnall and would be performed at our local theatre, the Watermill, we thought, huh, it never would have occurred to us to put this particular book on stage. Would it work? we wondered. The answer is yes and no, but it was entertaining and we were glad that we went. We presented tickets as my in-laws’ Christmas present and accompanied them to a mid-February matinee before supper at ours.

When we heard that Notes from a Small Island (1995), his account of a valedictory tour around Britain before returning to live in the States for the first time in 20 years, had been adapted into a play by Tim Whitnall and would be performed at our local theatre, the Watermill, we thought, huh, it never would have occurred to us to put this particular book on stage. Would it work? we wondered. The answer is yes and no, but it was entertaining and we were glad that we went. We presented tickets as my in-laws’ Christmas present and accompanied them to a mid-February matinee before supper at ours.

A few members of my book club decided to see the show later in the run and suggested we read – or reread, as was the case for several of us – the book in March. I started my reread before attending the play and had gotten through the first 50 pages, which is mostly about his first visit to England in 1973 (including a stay in a Dover boarding-house presided over by the infamously officious “Mrs Smegma”). This was ideal as the first bit contains the funniest stuff and, with the addition of some autobiographical material from later in the book plus his 2006 memoir The Life and Times of the Thunderbolt Kid, made up the entirety of the first act.

Photos are screenshots from the Watermill website.

Bryson traveled almost exclusively by public transport, so the set had the brick and steel walls of a generic terminal, and a bus shelter and benches were brought into service as the furnishing for most scenes. The problem with frontloading the play with hilarious scenes is that the second act, like the book itself on this reread, became rather a slog of random stops, acerbic observations, finding somewhere to stay and something to eat (often curry), and then doing it all over again.

Mark Hadfield, in the starring role, had the unenviable role of carrying the action and remembering great swathes of text lifted directly from the book. That’s all well and good as a strategy for giving a flavour of the writing style, but the language needed to be simplified; the poor man couldn’t cope and kept fluffing his lines. There were attempts to ease the burden: sections were read out by other characters in the form of announcements, letters or postcards; some reflections were played as if from Bryson’s Dictaphone. It was best, though, when there were scenes rather than monologues against a projected map, because there was an excellent ensemble cast of six who took on the various bit parts and these were often key occasions for humour: hotel-keepers, train-spotters, unintelligible accents in a Glasgow pub.

The trajectory was vaguely southeast to northwest – as far as John O’Groats, then back home to the Yorkshire Dales – but the actual route was erratic, based on whimsy as much as the availability of trains and buses. Bryson sings the praises of places like Salisbury and Durham and the pinnacles of coastal walks, and slates others, including some cities, seaside resorts and tourist traps. Places of personal significance make it onto his itinerary, such as the former mental asylum at Virginia Water, Surrey where he worked and met his wife in the 1970s. (My husband and I lived across the street from it for a year and a half.) He’s grumpy about having to pay admission fees that in today’s money sound minimal – £2.80 for Stonehenge!

The main interest for me in both book and play was the layers of recent history: the nostalgia for the old-fashioned country he discovered at a pivotal time in his own young life in the 1970s; the disappointments but still overall optimism of the 1990s; and the hindsight the reader or viewer brings to the material today. At a time when workers of every type seem to be on strike, it was poignant to read about the protests against Margaret Thatcher and the protracted printers’ strike of the 1980s.

The main interest for me in both book and play was the layers of recent history: the nostalgia for the old-fashioned country he discovered at a pivotal time in his own young life in the 1970s; the disappointments but still overall optimism of the 1990s; and the hindsight the reader or viewer brings to the material today. At a time when workers of every type seem to be on strike, it was poignant to read about the protests against Margaret Thatcher and the protracted printers’ strike of the 1980s.

The central message of the book, that Britain has an amazing heritage that it doesn’t adequately appreciate and is rapidly losing to homogenization, still holds. Yet I’m not sure the points about the at-heart goodness and politeness of the happy-with-their-lot British remain true. Is it just me or have general entitlement, frustration, rage and nastiness taken over? Not as notable as in the USA, but social divisions and the polarization of opinions are getting worse here, too. One can’t help but wonder what the picture would have been post-Brexit as well. Bryson wrote a sort-of sequel in 2015, The Road to Little Dribbling, in which the sarcasm and curmudgeonly persona override the warmth and affection of the earlier book.

The central message of the book, that Britain has an amazing heritage that it doesn’t adequately appreciate and is rapidly losing to homogenization, still holds. Yet I’m not sure the points about the at-heart goodness and politeness of the happy-with-their-lot British remain true. Is it just me or have general entitlement, frustration, rage and nastiness taken over? Not as notable as in the USA, but social divisions and the polarization of opinions are getting worse here, too. One can’t help but wonder what the picture would have been post-Brexit as well. Bryson wrote a sort-of sequel in 2015, The Road to Little Dribbling, in which the sarcasm and curmudgeonly persona override the warmth and affection of the earlier book.

Indeed, my book club noted that a lot of the jokes were things he couldn’t get away with saying today, and the theatre issued a content warning: “This production includes the use of very strong language, language reflective of historical attitudes around Mental Health, reference to drug use, sexual references, mention of suicide, flashing lights, pyrotechnics, loud sound effect explosions, and haze. This production is most suitable for those aged 12+.”

So, yes, an amusing journey, but a bittersweet one to revisit, and an odd choice for the stage.

A favourite line I’ll leave you with: “To this day, I remain impressed by the ability of Britons of all ages and social backgrounds to get genuinely excited by the prospect of a hot beverage.”

Book:

Original rating (c. 2004):

My rating now:

Play:

Have you read anything by Bill Bryson? Are you a fan?

Adventuring (and Reading) in the Outer Hebrides

Islands are irresistible for the unique identities they develop through isolation, and the extra effort that it often takes to reach them. Over the years, my husband and I have developed a special fondness for Britain’s islands – the smaller and more remote the better. After exploring the Inner Hebrides in 2005 and Orkney and Shetland in 2006, we always intended to see more of Scotland’s islands; why ever did we leave it this long?

Rail strikes and cancelled trains threatened our itinerary more than once, so it was a relief that we were able to go, even at extra cost. Our back-up plan left us with a spare day in Inverness, which we filled with coffee and pastries outside the cathedral, browsing at Leakey’s bookshop, walking along the River Ness and in the botanical gardens, and a meal overlooking the 19th-century castle.

Then it was on to the Outer Hebrides at last, via a bus ride and then a ferry to Stornoway in Lewis, the largest settlement in the Western Isles. Here we rented a car for a week to allow us to explore the islands at will. We were surprised at how major a town Stornoway is, with a big supermarket and slight suburban sprawl – yet it was dead on the Saturday morning we went in to walk around; not until 11:30 was there anything like the bustle we expected.

We’d booked three nights in a tiny Airbnb house 15 minutes from the capital. First up on our tourist agenda was Callanish stone circle, which we had to ourselves (once the German coach party left). Unlike at Stonehenge, you can walk in among the standing stones. The rest of our time on Lewis went to futile whale watching, the castle grounds, and beach walks.

This post threatens to become a boring rundown, so I’ll organize the rest thematically, introduced by songs by Scottish artists.

“I’ll Always Leave the Light On” by Kris Drever

Long days: The daylight lasts longer so far north, so each day we could plan activities not just for the morning and afternoon but late into the evening. At our second stop – three nights in another Airbnb on North Uist – we took walks after dinner, often not coming back until 10 p.m., at which point there was still another half-hour until sunset.

“Why Does It Always Rain on Me?” by Travis

Weather: We got a mixture of sun and clouds. It rained at least a bit on most days, and we got drenched twice, walking out to an eagle observatory on Harris (where we saw no eagles, as they are too sensible to fly in the rain) and dashing back to the car from a coastal excursion. I was doomed to wearing plastic bags around my feet inside my disintegrating hiking boots for the rest of the trip. There was also a strong wind much of the time, which made it feel colder than the temperature suggested – I often wore my fleece and winter hat.

A witty approach to weather forecasting. (Outside the shop/bistro on Berneray.)

“St Kilda Wren” by Julie Fowlis

Music and language: Julie Fowlis is a singer from North Uist who records in English and Gaelic. (This particular song is in Gaelic, but the whole Spell Songs album was perfect listening on our drives because of the several Scottish artists involved and the British plants and animals sung about.) There is a strong Gaelic-speaking tradition in the Western Isles. We heard a handful of people speaking it, all road signs give place names in Gaelic before the English translation, and there were several Gaelic pages in the free newspaper we picked up.

Music and language: Julie Fowlis is a singer from North Uist who records in English and Gaelic. (This particular song is in Gaelic, but the whole Spell Songs album was perfect listening on our drives because of the several Scottish artists involved and the British plants and animals sung about.) There is a strong Gaelic-speaking tradition in the Western Isles. We heard a handful of people speaking it, all road signs give place names in Gaelic before the English translation, and there were several Gaelic pages in the free newspaper we picked up.

Wildlife: The Outer Hebrides is a bastion for some rare birds: the corncrake, the red-necked phalarope, and both golden and white-tailed eagles. Thanks to intel gleaned from Twitter, my husband easily found a phalarope swimming in a small roadside loch. Corncrakes hide so well they are virtually impossible to see, but you will surely hear their rasping calls from the long grass. Balranald is the westernmost RSPB reserve and a wonderful place to hear corncrakes and see seabirds flying above the machair (wildflower-rich coastal grassland). No golden eagles, but we did see a white-tailed eagle flying over our accommodation on our last day, and short-eared owls were seemingly a dime a dozen. We were worried we might see lots of dead birds on our trip due to the avian flu raging, but there were only five – four gannets and an eider – and a couple looked long dead. Still, it’s a distressing situation.

We also attended an RSPB guided walk to look for otters and did indeed spot one on a sea loch. It happened to be the Outer Hebrides Wildlife Festival week. Our guide was knowledgeable about the geography and history of the islands as well.

Badges make great, cheap souvenirs!

St. Kilda: This uninhabited island really takes hold of the imagination. It can still be visited, but only via a small boat through famously rough seas. We didn’t chance it this time. I might never get there, but I enjoy reading about it. There’s a viewing point on North Uist where one can see out to St. Kilda, but it was only the vaguest of outlines on the hazy day we stopped.

“Traiveller’s Joy” by Emily Smith

Additional highlights:

- An extended late afternoon tea at Mollans rainbow takeaway shed on Lewis. Many of the other eateries we’d eyed up in the guidebook were closed, either temporarily or for good – perhaps an effect of Covid, which hit just after the latest edition was published.

- A long reading session with a view by the Butt of Lewis, which has a Stevenson lighthouse.

- Watching mum and baby seals playing by the spit outside our B&B window on Berneray.

- Peat smoked salmon. As much of it as I could get.

- A G&T with Harris gin (made with kelp).

“Dear Prudence” (Beatles cover) by Lau

Surprises:

- Gorgeous, deserted beaches. This is Luskentyre on Harris.

- No midges to speak of. The Highlands are notorious for these biting insects, but the wind kept them away most of the time we were on the islands. We only noticed them in the air on one still evening, but they weren’t even bad enough to deploy the Avon Skin So Soft we borrowed from a neighbour.

- People still cut and burn peats for fuel. Indeed, when we stepped into the Harris gin distillery for a look around, I was so cold and wet that I warmed my hands by a peat fire! Even into the 1960s, people lived in primitive blackhouses, some of which have now been restored as holiday rentals. The one below is run as a museum.

- Not far outside Stornoway is the tiny town of Tong. We passed through it each day. Here Mary Anne MacLeod was born in 1912. If only she’d stayed on Lewis instead of emigrating to New York City, where she met Fred Trump and had, among other children, a son named Donald…

- Lord Leverhulme, founder of Unilever, bought Lewis in 1918 and part of Harris the next year. He tried to get crofters to work in his businesses, but all his plans met with resistance and his time there was a failure, as symbolized by this “bridge to nowhere” (Garry Bridge). His legacy is portrayed very differently here compared to in Port Sunlight, the factory workers’ town he set up in Merseyside.

- The most far-flung Little Free Library I’ve ever visited (on Lewis).

- Visits from Lulu the cat at our North Uist Airbnb.

“Wrapped Up in Books” by Belle and Sebastian

What I read: I aimed for lots of relevant on-location reads. I can’t claim Book Serendipity: reading multiple novels set on Scottish islands, it’s no surprise if isolation, the history of the Clearances, boat rides, selkies and seabirds recur. However, the coincidences were notable for one pair, Secrets of the Sea House by Elisabeth Gifford and Night Waking by Sarah Moss, a reread for me. I’ll review these two together, as well as The Summer of the Bear by Bella Pollen (inspired by a real incident that occurred on North Uist in 1980), in full later this week.

I also read about half of Sightlines by Kathleen Jamie, a reread for me; its essays on gannets and St. Kilda chimed with the rest of my reading. Marram, Leonie Charlton’s memoir of pony trekking through the Outer Hebrides, will form part of a later 20 Books of Summer post thanks to the flora connection, as will Jon Dunn’s Orchid Summer, one chapter of which involves a jaunt to North Uist to find a rare species.

Stormy Petrel by Mary Stewart: My selection for the train journey up. I got Daphne du Maurier vibes from this short novel about a holiday Dr Rose Fenemore, an English tutor at Cambridge, takes to Moila, a (fictional) small island off of Mull in the Inner Hebrides. It’s a writing retreat for her: she’s working on a book of poetry, but also on the science fiction she publishes under a pseudonym. Waiting for her brother to join her, she gets caught up in mild intrigue when two mysterious men enter her holiday cottage late one stormy night. Each has a good excuse cooked up, but who can she trust? I enjoyed the details of the setting but found the plot thin, predictable and slightly silly (“I may be a dish, but I am also a don”). This feels like it’s from the 1950s, but was actually published in 1991. I might try another of Stewart’s.

Stormy Petrel by Mary Stewart: My selection for the train journey up. I got Daphne du Maurier vibes from this short novel about a holiday Dr Rose Fenemore, an English tutor at Cambridge, takes to Moila, a (fictional) small island off of Mull in the Inner Hebrides. It’s a writing retreat for her: she’s working on a book of poetry, but also on the science fiction she publishes under a pseudonym. Waiting for her brother to join her, she gets caught up in mild intrigue when two mysterious men enter her holiday cottage late one stormy night. Each has a good excuse cooked up, but who can she trust? I enjoyed the details of the setting but found the plot thin, predictable and slightly silly (“I may be a dish, but I am also a don”). This feels like it’s from the 1950s, but was actually published in 1991. I might try another of Stewart’s.

I also acquired four books on the trip: one from the Little Free Library and three from Inverness charity shops.

I started reading all three in the bottom pile, and read a few more books on my Kindle, two of them for upcoming paid reviews. The third was:

Tracy Flick Can’t Win by Tom Perrotta: A sequel to Election, which you might remember as a late-1990s Reese Witherspoon film even if you don’t know Perrotta’s fiction. Tracy Flick was the goody two-shoes student who ran for school president and had her campaign tampered with. Now in her forties, she’s an assistant principal at a high school and a single mother. Missing her late mother and wishing she’d completed law school, she fears she’ll be passed over for the top job when the principal retires. This is something of an attempt to update the author’s laddish style for the #MeToo era. Interspersed with the third-person narration are snappy first-person testimonials from Tracy, the principal, a couple of students, and the washed-up football star the school chooses to launch its new Hall of Fame. I can’t think of any specific objections, but nor can I think of any reason why you should read this.

Tracy Flick Can’t Win by Tom Perrotta: A sequel to Election, which you might remember as a late-1990s Reese Witherspoon film even if you don’t know Perrotta’s fiction. Tracy Flick was the goody two-shoes student who ran for school president and had her campaign tampered with. Now in her forties, she’s an assistant principal at a high school and a single mother. Missing her late mother and wishing she’d completed law school, she fears she’ll be passed over for the top job when the principal retires. This is something of an attempt to update the author’s laddish style for the #MeToo era. Interspersed with the third-person narration are snappy first-person testimonials from Tracy, the principal, a couple of students, and the washed-up football star the school chooses to launch its new Hall of Fame. I can’t think of any specific objections, but nor can I think of any reason why you should read this.

On my recommendation, my husband read Love of Country by Madeleine Bunting and The Frayed Atlantic Edge by David Gange, two excellent nonfiction books about Britain’s islands and coastline.

“Other Side of the World” by KT Tunstall

General impressions: We weren’t so taken with Lewis on the whole, but absolutely loved what we saw of Harris on our drive to the ferry to Berneray and wished we’d allotted it more time. While we only had one night on Berneray and mostly saw it in the rain, we thought it a lovely little place. It only has the one shop, which doubles as the bistro in the evenings – warned by the guidebook that this is the only place to eat on the island, we made our dinner reservation many weeks in advance. The following morning, as we ate our full Scottish cooked breakfast, I asked the B&B owner what led him to move from England to “the ends of the earth.” He took mild objection to my tossed-off remark and replied that the islands are more like “the heart of it all.” Thanks to fast Internet service, remote working is no issue.

We are more than half serious when we talk about moving to Scotland one day. We love Edinburgh, though the tourists might drive us mad, and enjoyed our time in Wigtown four years ago. I’d like to think we could even cope with island life in Orkney or the Hebrides. We imagine them having warm, tight-knit communities, but would newcomers feel welcome? With only one major supermarket in the whole Western Isles, would we find enough fresh fruit and veg? And however would one survive the bleakness of the winters?

North Uist captivated us right away, though. Within 15 minutes of driving onto the island via a causeway, we’d seen three short-eared owls and three red deer stags, and we got great views of hen harriers and other raptors. One evening we found ourselves under what seemed to be a raven highway. It felt unlike anywhere else we’d been: pleasingly empty of humans, and thus a wildlife haven.

The long journey home: The public transport nightmares of our return trip put something of a damper on the end of the holiday. We left the islands via a ferry to Skye, where we caught a bus. So far, so good. Our second bus, however, broke down in the middle of nowhere in the Highlands and the driver plus we five passengers were stuck for 3.5 hours awaiting a taxi we thought would never come. When it did, it drove the winding road at terrifying speed through the pitch black.

Grateful to be alive, we spent the following half-day in Edinburgh, bravely finding brunch, the botanic gardens and ice cream with our heavy luggage in tow. The final leg home, alas, was also disrupted when our overcrowded train to Reading was delayed and we missed the final connection to Newbury, necessitating another taxi – luckily, both were covered by the transport operators, and we’ll also reclaim for our tickets. Much as we believe in public transport and want to support it, this experience gave us pause. Getting to and around Spain by car was so much easier, and that trip ended up a lot cheaper, too. Ironic!

Guarding the bags in Edinburgh

“Take Me Back to the Islands” by Idlewild

Next time: On this occasion we only got as far south as Benbecula (which, pleasingly, is pronounced Ben-BECK-you-luh). In the future we’d think about starting at the southern tip and seeing Barra, Eriskay and South Uist before travelling up to Harris. We’ve heard that these all have their own personalities. Now, will we get back before many more years pass?