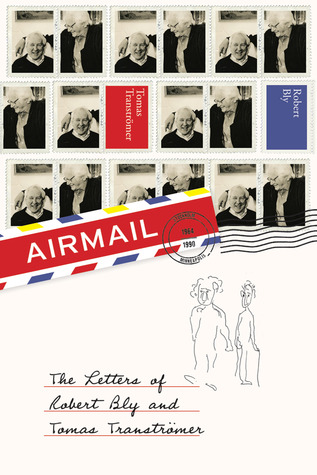

Airmail: Books that Lasted All of 2015 #2

Airmail: The Letters of Robert Bly and Tomas Tranströmer was my first-ever Goodreads giveaway win. Way back in the summer of 2013, the good people of Graywolf Press spent a small fortune to send this tremendous book all the way from Minnesota to my tiny then-house on the outskirts of Reading, England. It took me an unconscionably long time first to pick it up, then to read it, and finally to review it. But here we are.

Airmail: The Letters of Robert Bly and Tomas Tranströmer was my first-ever Goodreads giveaway win. Way back in the summer of 2013, the good people of Graywolf Press spent a small fortune to send this tremendous book all the way from Minnesota to my tiny then-house on the outskirts of Reading, England. It took me an unconscionably long time first to pick it up, then to read it, and finally to review it. But here we are.

This is the first time I’d read a literary correspondence, and I absolutely loved it. I knew very little about either poet before picking this up, though I recognized Bly as the translator of the copy of Knut Hamsun’s Hunger I had read a few years back. The two first corresponded in 1964 when Tranströmer requested a copy of the poetry journal The Sixties from Bly’s small press. At this point Tranströmer was already an established poet in his native Sweden, but in decades to come Bly was responsible for making his reputation in English translation.

“Friendships have their rhythms and seasons, fat times and lean times,” editor Thomas R. Smith writes in his introduction. One of the pleasures of this book is watching a friendship develop, as salutations go from “Dear Mr. Tranströmer” and “Best wishes” to “Your friend” and “With deep fondness always.”

Their relationship was both professional and personal: they translated each other’s poems into their respective languages so discussed intricacies of meaning as well as publication details and reading tours, but they also visited each other and became ever deeper confidants through deaths in the family and Bly’s painful divorce. They also commiserate over the debacle of the Vietnam War (as a protestor Bly was once arrested alongside Dr. Spock and Allen Ginsberg) and the Nixon–Reagan affronts to liberalism.

These letters sparkle with humor, especially from Tranströmer, who paints a Micawber-ish picture of his impecunious family, initially supported through his day job as a psychologist at a boys’ prison. My impression of him was of an impish joker.

Our shortage of money is comical—toward the end of the month we go around and shake all our old clothes in the hope that a stray coin might fall out.

We drank some champagne, which makes you think very clearly—my head turned into an aquarium with goldfish who were mumbling sentences of Marcus Aurelius.

Bly’s a witty sort, too:

I’ll send you the most insulting review I’ve ever gotten—it’s wonderful, he objects to everything about me except the size of my shoes!

I carefully set aside these free days which are known as Introvert Days, and are to be spent in solitary anxious, obstinate, confused ectomorph brooding.

Forgive my new typewriter—its mother was frightened by a Latin manuscript, and it doesn’t believe in pauses…

You don’t have to have any interest in poetry to read this with enjoyment. In fact, I didn’t care for most of the poem extracts. In the 1960s and 70s, at least – the heyday for the letters – they both wrote free verse poems that alternate matter-of-fact observations with abstractions. Lacking in sound techniques, they struck me as flat and artless. They weren’t to my taste apart from this one stanza of Tranströmer’s that instantly jumped out to me:

Two truths approach each other. One comes from inside, the other from outside, and where they meet we have a chance to catch sight of ourselves. (from “Preludes”)

However, Bly, at least, became “positively form-mad” in his later years; “[I] now have to eat all my words praising free verse as the only food conceivable for true Christian folk,” he wrote in 1981. He even created his own form, the “ramage” of 85 syllables. Perhaps I’ll like their later work better – I’m game for trying a full collection from each of them.

For anyone interested in the nitty-gritty of translation, there are many fascinating passages here where the poets wrestle with vocabulary and nuances. “Poems are best when there are incredible mysteries in them,” Bly declares, and all the more difficult to retain that mystery as they passed back and forth between Swedish and English. “I think it was something unexplainable, something water-like or flowing in our approach to poetry that made our translations of each other full of feeling even with occasional mistakes,” Bly wrote to their Swedish editor.

These selected letters continue through 1990, when Tranströmer had a stroke and their correspondence inevitably declined. Tomas Tranströmer would go on to win the Nobel Prize in 2011 and died in March 2015. Robert Bly is still going at age 89 and has recently been the subject of a biopic. Stealing Sugar from the Castle, a volume of his new and selected poems, was published in 2013.

After this I’d be keen to try out more authors’ correspondence volumes. I love letters whether they appear in epistolary fiction or in nonfiction, and here they form a touching picture of a friendship that sustained their writers for decades. In 1978 Bly wrote: “Thank you for receiving my grief and my uncertainties and my shadowy complications without running out the door.” That’s the mark of a true friend.

With thanks to Graywolf Press for the free copy, won in a Goodreads giveaway.

My rating:

Even when they’re in stanza form, these don’t necessarily read like poems; they’re often more like declaratory sentences, with the occasional out-of-place exclamation. But Bly’s eye is sharp as he describes the signs of the seasons, the sights and atmosphere of places he visits or passes through on the train (Ohio and Maryland get poems; his home state of Minnesota gets a whole section), and the small epiphanies of everyday life, whether alone or with friends. And the occasional short stanza hits like a wisdom-filled haiku, such as “There are palaces, boats, silence among white buildings, / Iced drinks on marble tops among cool rooms; / It is good also to be poor, and listen to the wind” (from “Poem against the British”).

Even when they’re in stanza form, these don’t necessarily read like poems; they’re often more like declaratory sentences, with the occasional out-of-place exclamation. But Bly’s eye is sharp as he describes the signs of the seasons, the sights and atmosphere of places he visits or passes through on the train (Ohio and Maryland get poems; his home state of Minnesota gets a whole section), and the small epiphanies of everyday life, whether alone or with friends. And the occasional short stanza hits like a wisdom-filled haiku, such as “There are palaces, boats, silence among white buildings, / Iced drinks on marble tops among cool rooms; / It is good also to be poor, and listen to the wind” (from “Poem against the British”).

One of the more inventive and surprising memoirs I’ve read. Growing up in Mississippi in the 1920s–30s, Gwin’s mother wanted nothing more than for it to snow. That wistfulness, a nostalgia tinged with bitterness, pervades the whole book. By the time her mother, Erin Clayton Pitner, a published though never particularly successful poet, died of ovarian cancer in the late 1980s, their relationship was a shambles. Erin’s mental health was shakier than ever – she stole flowers from the church altar, frequently ran her car off the road, and lived off canned green beans – and she never forgave Minrose for having had her committed to a mental hospital. Poring over Erin’s childhood diaries and adulthood vocabulary notebook, photographs, the letters and cards that passed between them, remembered and imagined conversations and monologues, and Erin’s darkly observant unrhyming poems (“No place to hide / from the leer of the sun / searching out every pothole, / every dream denied”), Gwin asks of her late mother, “When did you reach the point that everything was in pieces?”

One of the more inventive and surprising memoirs I’ve read. Growing up in Mississippi in the 1920s–30s, Gwin’s mother wanted nothing more than for it to snow. That wistfulness, a nostalgia tinged with bitterness, pervades the whole book. By the time her mother, Erin Clayton Pitner, a published though never particularly successful poet, died of ovarian cancer in the late 1980s, their relationship was a shambles. Erin’s mental health was shakier than ever – she stole flowers from the church altar, frequently ran her car off the road, and lived off canned green beans – and she never forgave Minrose for having had her committed to a mental hospital. Poring over Erin’s childhood diaries and adulthood vocabulary notebook, photographs, the letters and cards that passed between them, remembered and imagined conversations and monologues, and Erin’s darkly observant unrhyming poems (“No place to hide / from the leer of the sun / searching out every pothole, / every dream denied”), Gwin asks of her late mother, “When did you reach the point that everything was in pieces?”

It has been winter for five years, and Sanna, Mila and Pípa are left alone in their little house in the forest – with nothing but cabbages to eat – when their brother Oskar is lured away by the same evil force that took their father years ago and has been keeping spring from coming. Mila, the brave middle daughter, sets out on a quest to rescue Oskar and the village’s other lost boys and to find the way past winter. Clearly inspired by the Chronicles of Narnia and especially Katherine Arden’s Winternight trilogy, this middle grade novel is set in an evocative, if slightly vague, Russo-Finnish past and has more than a touch of the fairy tale about it. I enjoyed it well enough, but wouldn’t seek out anything else by the author.

It has been winter for five years, and Sanna, Mila and Pípa are left alone in their little house in the forest – with nothing but cabbages to eat – when their brother Oskar is lured away by the same evil force that took their father years ago and has been keeping spring from coming. Mila, the brave middle daughter, sets out on a quest to rescue Oskar and the village’s other lost boys and to find the way past winter. Clearly inspired by the Chronicles of Narnia and especially Katherine Arden’s Winternight trilogy, this middle grade novel is set in an evocative, if slightly vague, Russo-Finnish past and has more than a touch of the fairy tale about it. I enjoyed it well enough, but wouldn’t seek out anything else by the author. The translator’s introduction helped me understand the book better than I otherwise might have. I gleaned two key facts: 1) The mountainous west coast of Japan is snowbound for months of the year, so the title is fairly literal. 2) Hot springs were traditionally places where family men travelled without their wives to enjoy the company of geishas. Such is the case here with the protagonist, Shimamura, who is intrigued by the geisha Komako. Her flighty hedonism seems a good match for his, but they fail to fully connect. His attentions are divided between Komako and Yoko, and a final scene that is surprisingly climactic in a novella so low on plot puts the three and their relationships in danger. I liked the appropriate atmosphere of chilly isolation; the style reminded me of what little I’ve read from Marguerite Duras. I also thought of

The translator’s introduction helped me understand the book better than I otherwise might have. I gleaned two key facts: 1) The mountainous west coast of Japan is snowbound for months of the year, so the title is fairly literal. 2) Hot springs were traditionally places where family men travelled without their wives to enjoy the company of geishas. Such is the case here with the protagonist, Shimamura, who is intrigued by the geisha Komako. Her flighty hedonism seems a good match for his, but they fail to fully connect. His attentions are divided between Komako and Yoko, and a final scene that is surprisingly climactic in a novella so low on plot puts the three and their relationships in danger. I liked the appropriate atmosphere of chilly isolation; the style reminded me of what little I’ve read from Marguerite Duras. I also thought of