Six Degrees of Separation: From Sorrow and Bliss to Weather

This month we begin with Sorrow and Bliss by Meg Mason. (See also Kate’s opening post.) This is my personal favourite from the Women’s Prize shortlist and couldn’t be a better pick for the Six Degrees starter this month because I’ll be skimming back through the novel this weekend in advance of my book club’s discussion of it on Monday. (We’re one of this year’s six book groups shadowing the Women’s Prize through a Reading Agency initiative, so we then have to give semi-official feedback on our experience of the book by Wednesday.)

#1 Sorrow and Bliss is a terrific tragicomedy about sisterhood and mental health – as is All My Puny Sorrows by Miriam Toews, with which it shares a loaded title word as well.

#1 Sorrow and Bliss is a terrific tragicomedy about sisterhood and mental health – as is All My Puny Sorrows by Miriam Toews, with which it shares a loaded title word as well.

#2 Toews grew up in a Canadian Mennonite community, which leads me to my second choice, Mennonite in a Little Black Dress by Rhoda Janzen, a set of droll autobiographical essays that I read on a USA trip in 2017.

#2 Toews grew up in a Canadian Mennonite community, which leads me to my second choice, Mennonite in a Little Black Dress by Rhoda Janzen, a set of droll autobiographical essays that I read on a USA trip in 2017.

#3 During the same trip, I read Dear American Airlines by Jonathan Miles, a witty novel about Bennie Ford’s rather miserable life, presented in the form of his longwinded complaint letter to the airline that has treated him to an unexpected overnight layover in Chicago.

#3 During the same trip, I read Dear American Airlines by Jonathan Miles, a witty novel about Bennie Ford’s rather miserable life, presented in the form of his longwinded complaint letter to the airline that has treated him to an unexpected overnight layover in Chicago.

#4 Another laugh-out-loud book in the form of unlikely letters: Dear Committee Members by Julie Schumacher, in which Jason Fitger, an irascible middle-aged English professor in the Midwest, writes ambivalent letters of recommendation for students and colleagues.

#4 Another laugh-out-loud book in the form of unlikely letters: Dear Committee Members by Julie Schumacher, in which Jason Fitger, an irascible middle-aged English professor in the Midwest, writes ambivalent letters of recommendation for students and colleagues.

#5 One more “Dear” book of letters – I just can’t get enough of the epistolary form: Dear Fahrenheit 451 by Annie Spence. As the subtitle states, it’s a librarian’s love letters and breakup notes to books she’s adored and loathed. Casual and amusing, with good book recs.

#5 One more “Dear” book of letters – I just can’t get enough of the epistolary form: Dear Fahrenheit 451 by Annie Spence. As the subtitle states, it’s a librarian’s love letters and breakup notes to books she’s adored and loathed. Casual and amusing, with good book recs.

#6 I’ll finish with Weather by Jenny Offill, one of my favourites from 2020, which is also voiced by a librarian. Through Lizzie, Offill captures modern anxiety about Trump-era politics, the climate crisis and making meaningful use of time.

#6 I’ll finish with Weather by Jenny Offill, one of my favourites from 2020, which is also voiced by a librarian. Through Lizzie, Offill captures modern anxiety about Trump-era politics, the climate crisis and making meaningful use of time.

I have read all the books in this month’s chain (the links above are to my Goodreads reviews), and in a time of relentless bad news have chosen to prioritize humour and keep my descriptions short and light. These are all books that made me laugh, sometimes despite their weighty content, and half of them are built around letters. I’ve also looped from one Women’s Prize-shortlisted title to another.

Where will your chain take you? Join us for #6Degrees of Separation! (Hosted on the first Saturday of each month by Kate W. of Books Are My Favourite and Best.) Next month’s starting point will be Wintering by Katherine May – though it’s summer here, it’s winter where Kate is in Australia!

Have you read any of my selections? Tempted by any you didn’t know before?

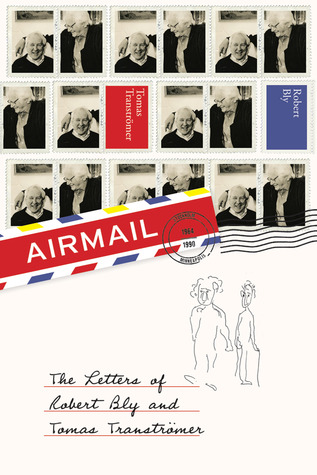

Airmail: Books that Lasted All of 2015 #2

Airmail: The Letters of Robert Bly and Tomas Tranströmer was my first-ever Goodreads giveaway win. Way back in the summer of 2013, the good people of Graywolf Press spent a small fortune to send this tremendous book all the way from Minnesota to my tiny then-house on the outskirts of Reading, England. It took me an unconscionably long time first to pick it up, then to read it, and finally to review it. But here we are.

Airmail: The Letters of Robert Bly and Tomas Tranströmer was my first-ever Goodreads giveaway win. Way back in the summer of 2013, the good people of Graywolf Press spent a small fortune to send this tremendous book all the way from Minnesota to my tiny then-house on the outskirts of Reading, England. It took me an unconscionably long time first to pick it up, then to read it, and finally to review it. But here we are.

This is the first time I’d read a literary correspondence, and I absolutely loved it. I knew very little about either poet before picking this up, though I recognized Bly as the translator of the copy of Knut Hamsun’s Hunger I had read a few years back. The two first corresponded in 1964 when Tranströmer requested a copy of the poetry journal The Sixties from Bly’s small press. At this point Tranströmer was already an established poet in his native Sweden, but in decades to come Bly was responsible for making his reputation in English translation.

“Friendships have their rhythms and seasons, fat times and lean times,” editor Thomas R. Smith writes in his introduction. One of the pleasures of this book is watching a friendship develop, as salutations go from “Dear Mr. Tranströmer” and “Best wishes” to “Your friend” and “With deep fondness always.”

Their relationship was both professional and personal: they translated each other’s poems into their respective languages so discussed intricacies of meaning as well as publication details and reading tours, but they also visited each other and became ever deeper confidants through deaths in the family and Bly’s painful divorce. They also commiserate over the debacle of the Vietnam War (as a protestor Bly was once arrested alongside Dr. Spock and Allen Ginsberg) and the Nixon–Reagan affronts to liberalism.

These letters sparkle with humor, especially from Tranströmer, who paints a Micawber-ish picture of his impecunious family, initially supported through his day job as a psychologist at a boys’ prison. My impression of him was of an impish joker.

Our shortage of money is comical—toward the end of the month we go around and shake all our old clothes in the hope that a stray coin might fall out.

We drank some champagne, which makes you think very clearly—my head turned into an aquarium with goldfish who were mumbling sentences of Marcus Aurelius.

Bly’s a witty sort, too:

I’ll send you the most insulting review I’ve ever gotten—it’s wonderful, he objects to everything about me except the size of my shoes!

I carefully set aside these free days which are known as Introvert Days, and are to be spent in solitary anxious, obstinate, confused ectomorph brooding.

Forgive my new typewriter—its mother was frightened by a Latin manuscript, and it doesn’t believe in pauses…

You don’t have to have any interest in poetry to read this with enjoyment. In fact, I didn’t care for most of the poem extracts. In the 1960s and 70s, at least – the heyday for the letters – they both wrote free verse poems that alternate matter-of-fact observations with abstractions. Lacking in sound techniques, they struck me as flat and artless. They weren’t to my taste apart from this one stanza of Tranströmer’s that instantly jumped out to me:

Two truths approach each other. One comes from inside, the other from outside, and where they meet we have a chance to catch sight of ourselves. (from “Preludes”)

However, Bly, at least, became “positively form-mad” in his later years; “[I] now have to eat all my words praising free verse as the only food conceivable for true Christian folk,” he wrote in 1981. He even created his own form, the “ramage” of 85 syllables. Perhaps I’ll like their later work better – I’m game for trying a full collection from each of them.

For anyone interested in the nitty-gritty of translation, there are many fascinating passages here where the poets wrestle with vocabulary and nuances. “Poems are best when there are incredible mysteries in them,” Bly declares, and all the more difficult to retain that mystery as they passed back and forth between Swedish and English. “I think it was something unexplainable, something water-like or flowing in our approach to poetry that made our translations of each other full of feeling even with occasional mistakes,” Bly wrote to their Swedish editor.

These selected letters continue through 1990, when Tranströmer had a stroke and their correspondence inevitably declined. Tomas Tranströmer would go on to win the Nobel Prize in 2011 and died in March 2015. Robert Bly is still going at age 89 and has recently been the subject of a biopic. Stealing Sugar from the Castle, a volume of his new and selected poems, was published in 2013.

After this I’d be keen to try out more authors’ correspondence volumes. I love letters whether they appear in epistolary fiction or in nonfiction, and here they form a touching picture of a friendship that sustained their writers for decades. In 1978 Bly wrote: “Thank you for receiving my grief and my uncertainties and my shadowy complications without running out the door.” That’s the mark of a true friend.

With thanks to Graywolf Press for the free copy, won in a Goodreads giveaway.

My rating:

This is the second short, somewhat harrowing autobiographical work I’ve read by Ernaux this year (after

This is the second short, somewhat harrowing autobiographical work I’ve read by Ernaux this year (after  A man wakes up from a dream convinced that his wife is cheating on him, and sets off for Tokyo on a whim, where he embarks on a Bashō-inspired pilgrimage to the pine islands of Matsushima. This Gilbert Silvester, a beard historian, acquires an unlikely companion: a young man named Yosa, who’s looking for the best place to kill himself and takes Gilbert along to cliffs and forests famous for their suicide rates. Although there are still cherry blossoms and kabuki theatre, Gilbert soon learns that this isn’t Bashō’s Japan anymore.

A man wakes up from a dream convinced that his wife is cheating on him, and sets off for Tokyo on a whim, where he embarks on a Bashō-inspired pilgrimage to the pine islands of Matsushima. This Gilbert Silvester, a beard historian, acquires an unlikely companion: a young man named Yosa, who’s looking for the best place to kill himself and takes Gilbert along to cliffs and forests famous for their suicide rates. Although there are still cherry blossoms and kabuki theatre, Gilbert soon learns that this isn’t Bashō’s Japan anymore.