Winter Reads: Claire Tomalin, Daniel Woodrell & Picture Books

Mid-February approaches and we’re wondering if the snowdrops and primroses emerging here in the South of England mean that it will be farewell to winter soon, or if the cold weather will return as rumoured. (Punxsutawney Phil didn’t see his shadow, but that early-spring prediction is only valid for the USA, right?) I didn’t manage to read many seasonal books this year, but I did pick up several short works with “Winter” in the title: a little-known biographical play from a respected author, a gritty Southern Gothic novella made famous through a Jennifer Lawrence film, and two picture books I picked up at the library last week.

The Winter Wife by Claire Tomalin (1991)

A search of the university library catalogue turned up this Tomalin title I’d never heard of. It turns out to be a very short play (two acts of seven scenes each, but only running to 44 pages in total) about a trip abroad Katherine Mansfield took with her housekeeper?/companion, Ida Baker, in 1920. Ida clucks over Katherine like a nurse or mother hen, but there also seems to be latent, unrequited love there (Mansfield was bisexual, as I knew from fellow New Zealander Sarah Laing’s fab graphic memoir Mansfield and Me). Katherine, for her part, alternately speaks to Ida, whom she nicknames “Jones,” with exasperation and fondness. The title comes from a moment late on when Katherine tells Ida “you’re the perfect friend – more than a friend. You know what you are, you’re what every woman needs: you’re my true wife.” Maybe what we’d call a “work wife” today, but Ida blushes with pride.

Tomalin had already written a full-length biography of Mansfield, but insists she barely referred to it when composing this. The backdrops are minimal: a French sleeper train; Isola Bella, a villa on the French Riviera; and Dr. Bouchage’s office. Mansfield was ill with tuberculosis, and the continental climate was a balm: “The sun gets right into my bones and makes me feel better. All that English damp was killing me. I can’t think why I ever tried to live in England.” There are also financial worries. The Murrys keep just one servant, Marie, a middle-aged French woman who accompanies her on this trip, but Katherine fears they’ll have to let her go if she doesn’t keep earning by her pen.

Through Katherine’s conversations with the doctor, we catch up on her romantic history – a brief first marriage, a miscarriage, and other lovers. Dr. Bouchage believes her infertility is a result of untreated gonorrhea. He echoes Ida in warning Katherine that she’s working too hard – mostly reviewing books for her husband John Middleton Murry’s magazine, but also writing her own short stories – when she should be resting. Katherine retorts, “It is simply none of your business, Jones. Dr Bouchage: if I do not work, I might as well be dead, it’s as simple as that.”

She would die not three years later, a fact that audiences learn through a final flash-forward where Ida, in a monologue, contrasts her own long life (she lived to 90 and Tomalin interviewed her when she was 88) with Katherine’s short one. “I never married. For me, no one ever equalled Katie. There was something golden about her.” Whereas Katherine had mused, “I thought there was going to be so much life then … that it would all be experience I could use. I thought I could live all sorts of different lives, and be unscathed…”

The play is, by its nature, slight, but gives a lovely sense of the subject and her key relationships – I do mean to read more by and about Mansfield. I wonder if it has been performed much since. And how about this for unexpected literary serendipity?

Yes, it’s that Rachel Joyce. (University library)

Winter’s Bone by Daniel Woodrell (2006)

I’d seen the movie but hadn’t remembered just how bleak and violent the story is, especially considering that the main character is a teenage girl. Ree Dolly lives in Ozarks poverty with a mentally ill, almost catatonic mother and two younger brothers whom she is effectively raising on her own. Their father, Jessup, is missing; rumour has it that he lies dead somewhere for snitching on his fellow drug producers. But unless Ree can prove he’s not coming back, the bail bondsman will repossess the house, leaving the family destitute.

I’d seen the movie but hadn’t remembered just how bleak and violent the story is, especially considering that the main character is a teenage girl. Ree Dolly lives in Ozarks poverty with a mentally ill, almost catatonic mother and two younger brothers whom she is effectively raising on her own. Their father, Jessup, is missing; rumour has it that he lies dead somewhere for snitching on his fellow drug producers. But unless Ree can prove he’s not coming back, the bail bondsman will repossess the house, leaving the family destitute.

Forced to undertake a frozen odyssey to find traces of Jessup, she’s unwelcome everywhere she goes, even among extended family. No one is above hitting a girl, it seems, and just for asking questions Ree gets beaten half to death. Her only comfort is in her best friend, Gail, who’s recently given birth and married the baby daddy. Gail and Ree have long “practiced” on each other romantically. Without labelling anything, Woodrell sensitively portrays the different value the two girls place on their attachment. His prose is sometimes gorgeous –

Pine trees with low limbs spread over fresh snow made a stronger vault for the spirit than pews and pulpits ever could.

– but can be overblown or off-puttingly folksy:

Ree felt bogged and forlorn, doomed to a spreading swamp of hateful obligations.

Merab followed the beam and led them on a slow wamble across a rankled field

This was my second from Woodrell, after the short stories of The Outlaw Album. I don’t think I’ll need to try any more by him, but this was a solid read. (Secondhand – New Chapter Books, Wigtown)

Children’s picture books:

Winter Sleep: A Hibernation Story by Sean Taylor and Alex Morss [illus. Cinyee Chiu] (2019): My second book by this group; I read Busy Spring: Nature Wakes Up a couple of years ago. Granny Sylvie reassures her grandson that everything hasn’t died in winter, but is sleeping or in hiding beneath the ice or behind the scenes. As before, the only niggle is that European and North American species are both mentioned and it’s not made clear that they live in different places. (Public library)

Winter Sleep: A Hibernation Story by Sean Taylor and Alex Morss [illus. Cinyee Chiu] (2019): My second book by this group; I read Busy Spring: Nature Wakes Up a couple of years ago. Granny Sylvie reassures her grandson that everything hasn’t died in winter, but is sleeping or in hiding beneath the ice or behind the scenes. As before, the only niggle is that European and North American species are both mentioned and it’s not made clear that they live in different places. (Public library)

The Lightbringers: Winter by Karin Celestine (2020): An unusual artistic style here: every spread is a photograph of felted woodland creatures. The focus is on midwinter and the hope of the light coming back – depicted as poppy seed heads, lit from within and carried by mouse, hare, badger and more. “The light will always return because it is guarded by small beings and they are steadfast in their task.” The first of four seasonal stories. (Public library)

The Lightbringers: Winter by Karin Celestine (2020): An unusual artistic style here: every spread is a photograph of felted woodland creatures. The focus is on midwinter and the hope of the light coming back – depicted as poppy seed heads, lit from within and carried by mouse, hare, badger and more. “The light will always return because it is guarded by small beings and they are steadfast in their task.” The first of four seasonal stories. (Public library)

Any wintry reading (or weather) for you lately?

Be(com)ing an ‘Expert’ on Postpartum Depression for #NonficNov

This Being/Becoming/Asking the Expert week of the month-long Nonfiction November challenge is hosted by Rennie of What’s Nonfiction.

I’m also counting this as the first entry in my new “Three on a Theme” series, where I’ll review three books that have something significant in common and tell you which one to pick up if you want to read into the topic for yourself. I have another medical-themed one lined up for this Friday as a second ‘Being the Expert’ entry.

I never set out to read several memoirs of women’s experience of postpartum depression this year; it sort of happened by accident. I started with the graphic memoir and then chanced upon a recent pair of traditional memoirs published in the UK – in fact, I initially pitched them as a dual review to the TLS, but they’d already secured a reviewer for one of the books.

Inferno: A Memoir by Catherine Cho

I was delighted to see this prediction of mine make the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award shortlist. Coincidentally, I was already halfway through the book on my Kindle (via NetGalley) at that point, but its nomination gave me the push to finish in a timely manner. Cho, a Korean American literary agent based in London, experienced stress-induced postpartum psychosis after the birth of her son, Cato. She and her husband James had gone back to the USA when Cato was two months old to introduce him to friends and family, ending with a big Korean 100-day celebration for him at her in-laws’ home in New Jersey. Almost as soon as they got to her in-laws’, though, she started acting strangely: she was convinced there were cameras watching their every move, and Cato’s eyes were replaced with “devil’s eyes.” She insisted they leave for a hotel, but soon she would be in an emergency room, followed by a mental health ward.

I was delighted to see this prediction of mine make the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award shortlist. Coincidentally, I was already halfway through the book on my Kindle (via NetGalley) at that point, but its nomination gave me the push to finish in a timely manner. Cho, a Korean American literary agent based in London, experienced stress-induced postpartum psychosis after the birth of her son, Cato. She and her husband James had gone back to the USA when Cato was two months old to introduce him to friends and family, ending with a big Korean 100-day celebration for him at her in-laws’ home in New Jersey. Almost as soon as they got to her in-laws’, though, she started acting strangely: she was convinced there were cameras watching their every move, and Cato’s eyes were replaced with “devil’s eyes.” She insisted they leave for a hotel, but soon she would be in an emergency room, followed by a mental health ward.

Cho alternates between her time on the New Bridge ward – writing in a notebook, trying to act normal whenever James visited, expressing milk from painfully swollen breasts, and interacting with her fellow patients with all their quirks – and a rundown of the rest of her life before the breakdown. Her Kentucky childhood was marked by her mathematician father’s detachment and the sense that she and her brother were together “in the trenches,” pitted against the world. In her twenties she worked in a New York City corporate law firm and got caught up in an abusive relationship with a man she moved to Hong Kong to be with. All along she weaves in her family’s history and Korean sayings and legends that explain their values.

Twelve days. That was the length of her hospitalization in early 2018, but Cho so painstakingly depicts her mindset that readers are fully immersed in an open-ended purgatory – a terrifying time when she questioned her sanity and whether she was cut out for motherhood. “Koreans believe that happiness can only tempt the fates and that any happiness must be bought with sorrow,” she writes. She captures both extremes, of suffering and joy, in this vivid account.

My rating:

What Have I Done? An honest memoir about surviving postnatal mental illness by Laura Dockrill

Dockrill is a British children’s author. Her style reminded me of others of her contemporaries who do a good line in light, witty, warts-and-all, here’s-what-it’s-really-like-to-be-a-woman books: Dolly Alderton, Caitlin Moran and the like. From a labor that quickly deviated from her birth plan due to an emergency Caesarean to the usual post-baby blues to full-blown psychosis, Dockrill recreates her experience with fluid dialogue and italicized passages of her paranoid imaginings. Her memoir resembles Cho’s in its broad strokes but also in certain particulars, like imagining surveillance cameras and hearing a voice in her head telling her she is a bad mum. I skimmed this one because of a library deadline and because of an overload on similar content. I had a greater affinity for Cho’s literary style compared to the more between-girlfriends, self-help bent of this memoir. With the glossary and resources at the end, though, I’d say this one would be more useful for someone going through the same thing.

Dockrill is a British children’s author. Her style reminded me of others of her contemporaries who do a good line in light, witty, warts-and-all, here’s-what-it’s-really-like-to-be-a-woman books: Dolly Alderton, Caitlin Moran and the like. From a labor that quickly deviated from her birth plan due to an emergency Caesarean to the usual post-baby blues to full-blown psychosis, Dockrill recreates her experience with fluid dialogue and italicized passages of her paranoid imaginings. Her memoir resembles Cho’s in its broad strokes but also in certain particulars, like imagining surveillance cameras and hearing a voice in her head telling her she is a bad mum. I skimmed this one because of a library deadline and because of an overload on similar content. I had a greater affinity for Cho’s literary style compared to the more between-girlfriends, self-help bent of this memoir. With the glossary and resources at the end, though, I’d say this one would be more useful for someone going through the same thing.

My rating:

Dear Scarlet: The Story of My Postpartum Depression by Teresa Wong (2019)

Memoir as letter and as graphic novel. Wong narrates the traumatic birth of her first child and her subsequent postpartum depression in black-and-white sketches that manage to feel breezy and fun despite the heavy subject matter. “I felt lost. I had no maternal instincts and no clue how I was supposed to take care of a baby,” she writes to Scarlet. “Your first two months in the world were the hardest two months of my life.”

Memoir as letter and as graphic novel. Wong narrates the traumatic birth of her first child and her subsequent postpartum depression in black-and-white sketches that manage to feel breezy and fun despite the heavy subject matter. “I felt lost. I had no maternal instincts and no clue how I was supposed to take care of a baby,” she writes to Scarlet. “Your first two months in the world were the hardest two months of my life.”

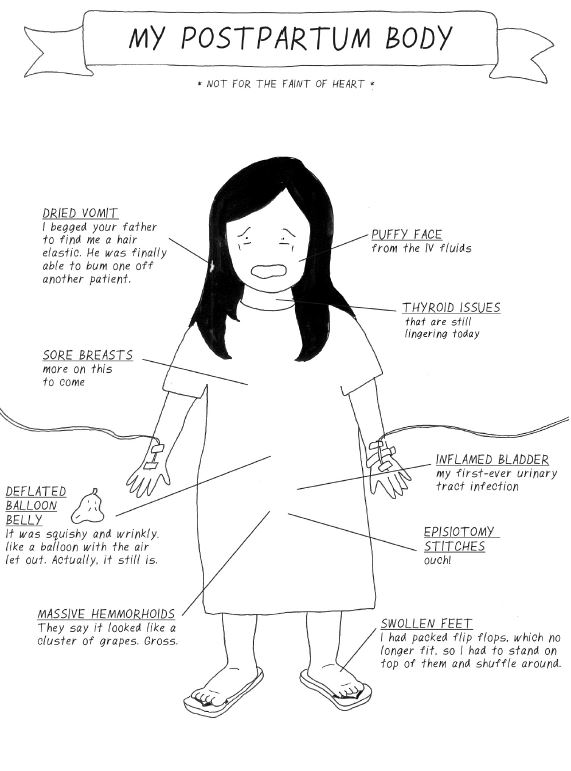

For Wong, a combination of antidepressants, therapy, a postnatal doula, an exercise class, her mother’s help, and her husband’s constant support got her through, and she knows she’s lucky to have had a fairly mild case and to have gotten assistance early on. I loved the “Not for the Faint of Heart” anatomical spreads and the reflections on her mother’s tough early years after arriving in Canada from China.

The drawing and storytelling style is similar to that of Sarah Laing and Debbie Tung. The writing is more striking than the art, though, so I hope that with future work the author will challenge herself to use more color and more advanced designs (from her Instagram page it looks like she is heading that way).

My rating:

My thanks to publicist Beth Parker for the free e-copy for review.

What I learned:

All three authors emphasize that motherhood does not always come naturally; “You might not instantly love your baby,” as Dockrill puts it. There might be a feeling of detachment – from the baby and/or from one’s new body. They all note that postpartum depression is common and that new mothers should not be ashamed of seeking help from medical professionals, baby nurses, family members and any other sources of support.

These two passages were representative for me:

Cho: “I don’t feel a rush of love or an overwhelming weight of responsibility, emotions that I’d been expecting. Instead, I felt curious, like I’d just been introduced to a stranger. He was a creature, an idea, not even human yet, just a being, a life. … I’d thought I would reclaim my body after birth, but instead, it was now a tool, something to sustain life.”

Dockrill: “If childbirth and motherhood are the most natural, universal, common things in the world, the things that women have been doing since the beginning of time, then why does nobody tell us that there’s a good chance that you might not feel like yourself after you have a baby? That you might even lose your head? That you might not ever come back?”

On this topic, I have also read: Birth of a New Brain by Dyane Harwood. There are more book ideas here and here.

On this topic, I have also read: Birth of a New Brain by Dyane Harwood. There are more book ideas here and here.

Nobody Told Me by Hollie McNish, one of my current bedside books, also deals with complicated pregnancy emotions and the chaotic early months of motherhood.

If you read just one, though… Make it Inferno by Catherine Cho.