Women’s Prize 2022: Longlist Wishes vs. Predictions

Next Tuesday the 8th, the 2022 Women’s Prize longlist will be announced.

First I have a list of 16 novels I want to be longlisted, because I’ve read and loved them (or at least thought they were interesting), or am currently reading and enjoying them, or plan to read them soon, or am desperate to get hold of them.

Wishlist

Brown Girls by Daphne Palasi Andreades

Our Wives Under the Sea by Julia Armfield (my review)

Ghosted by Jenn Ashworth (my review)

These Days by Lucy Caldwell

Damnation Spring by Ash Davidson – currently reading

Olga Dies Dreaming by Xóchitl González – currently reading

Burntcoat by Sarah Hall (my review)

Early Morning Riser by Katherine Heiny (my review)

Pure Colour by Sheila Heti

My Monticello by Jocelyn Nicole Johnson (my review)

Devotion by Hannah Kent – currently reading

Build Your House Around My Body by Violet Kupersmith – currently reading

When the Stars Go Dark by Paula McLain (my review)

The Swimmers by Julie Otsuka – review coming to Shiny New Books on Thursday

Brood by Jackie Polzin (my review)

The Performance by Claire Thomas (my review)

Then I have a list of 16 novels I think will be longlisted mostly because of the buzz around them, or they’re the kind of thing the Prize always recognizes (like danged GREEK MYTHS), or they’re authors who have been nominated before – previous shortlistees get a free pass when it comes to publisher submissions, you see – or they’re books I might read but haven’t gotten to yet.

Predictions

Love Marriage by Monica Ali

When We Were Birds by Ayanna Lloyd Banwo

Second Place by Rachel Cusk (my review)

Matrix by Lauren Groff

Free Love by Tessa Hadley

The Other Black Girl by Zakiya Dalila Harris (my review)

The Love Songs of W.E.B. Du Bois by Honorée Fanonne Jeffers

The Fell by Sarah Moss (my review)

My Phantoms by Gwendoline Riley

Beautiful World, Where Are You by Sally Rooney (my review)

Ariadne by Jennifer Saint

The Island of Missing Trees by Elif Shafak

Great Circle by Maggie Shipstead

Pandora by Susan Stokes-Chapman

Still Life by Sarah Winman

To Paradise by Hanya Yanagihara – currently reading

*A wildcard entry that could fit on either list: Sorrow and Bliss by Meg Mason (my review).*

Okay, no more indecision and laziness. Time to combine these two into a master list that reflects my taste but also what the judges of this prize generally seem to be looking for. It’s been a year of BIG books – seven of these are over 400 pages; three of them over 600 pages even – and a lot of historical fiction, but also some super-contemporary stuff. Seven BIPOC authors as well, which would be an improvement over last year’s five and closer to the eight from two years prior. A caveat: I haven’t given thought to publisher quotas here.

MY WOMEN’S PRIZE FORECAST

Love Marriage by Monica Ali

Our Wives Under the Sea by Julia Armfield

When We Were Birds by Ayanna Lloyd Banwo

Olga Dies Dreaming by Xóchitl González

Matrix by Lauren Groff

The Love Songs of W.E.B. Du Bois by Honorée Fanonne Jeffers

Devotion by Hannah Kent

Build Your House Around My Body by Violet Kupersmith

The Fell by Sarah Moss

My Phantoms by Gwendoline Riley

Beautiful World, Where Are You by Sally Rooney

Ariadne by Jennifer Saint

The Island of Missing Trees by Elif Shafak

Great Circle by Maggie Shipstead

Pandora by Susan Stokes-Chapman

To Paradise by Hanya Yanagihara

What do you think?

See also Laura’s, Naty’s, and Rachel’s predictions (my final list overlaps with theirs on 10, 5 and 8 titles, respectively) and Susan’s wishes.

Just to further overwhelm you, here are the other 62 eligible 2021–22 novels that were on my radar but didn’t make the cut:

In Every Mirror She’s Black by Lola Akinmade Åkerström

Violeta by Isabel Allende

The Leviathan by Rosie Andrews

Somebody Loves You by Mona Arshi

The Stars Are Not Yet Bells by Hannah Lillith Assadi

The Manningtree Witches by A.K. Blakemore

Mary Jane by Jessica Anya Blau

Defenestrate by Renee Branum

Songs in Ursa Major by Emma Brodie

Assembly by Natasha Brown

We Were Young by Niamh Campbell

The Raptures by Jan Carson

A Very Nice Girl by Imogen Crimp

Scary Monsters by Michelle de Kretser

Empire of Wild by Cherie Dimaline

Infinite Country by Patricia Engel

Love & Saffron by Kim Fay

Mrs March by Virginia Feito

Booth by Karen Joy Fowler

Tides by Sara Freeman

I Couldn’t Love You More by Esther Freud

Of Women and Salt by Gabriela Garcia

Libertie by Kaitlyn Greenidge

Listening Still by Anne Griffin

The Twyford Code by Janice Hallett

Mrs England by Stacey Halls

Three Rooms by Jo Hamya

The Giant Dark by Sarvat Hasin

The Paper Palace by Miranda Cowley Heller

Violets by Alex Hyde

Fault Lines by Emily Itami

Beasts of a Little Land by Juhea Kim

Woman, Eating by Claire Kohda

Notes on an Execution by Danya Kukafka

Paul by Daisy Lafarge

Circus of Wonders by Elizabeth Macneal

The Truth About Her by Jacqueline Maley

Wahala by Nikki May

Once There Were Wolves by Charlotte McConaghy

Cleopatra and Frankenstein by Coco Mellors

The Exhibitionist by Charlotte Mendelson

Chouette by Claire Oshetsky

The Book of Form and Emptiness by Ruth Ozeki

The Anthill by Julianne Pachico

The Vixen by Francine Prose

The Five Wounds by Kirstin Valdez Quade

Malibu Rising by Taylor Jenkins Reid

Cut Out by Michèle Roberts

This One Sky Day by Leone Ross

Secrets of Happiness by Joan Silber

Cold Sun by Anita Sivakumaran

Hear No Evil by Sarah Smith

Oh William! by Elizabeth Strout

Animal by Lisa Taddeo

Daughter of the Moon Goddess by Sue Lynn Tan

Lily by Rose Tremain

French Braid by Anne Tyler

We Run the Tides by Vendela Vida

I Love You but I’ve Chosen Darkness by Claire Vaye Watkins

Black Cake by Charmaine Wilkerson

The Dictionary of Lost Words by Pip Williams

Nightbitch by Rachel Yoder

Catching Up: Mini Reviews of Some Notable Reads from Last Year

I do all my composition on an ancient PC (unconnected to the Internet) in a corner of our lounge. On top of the CPU sit piles of books waiting to be reviewed. Some have been residing there for an embarrassingly long time since I finished reading them; others were only recently added to the stack but had previously languished on my set-aside shelf. I think the ‘oldest’ of the set below is the Olson, which I started reading in November 2019. In every case, the book earned a spot on the pile because I felt it was worth a review, but I’ll stick to a brief paragraph on why each was memorable. Bonus: I get my Post-its back, and can reshelve the books so they get packed sensibly for our upcoming move.

Fiction

How Should a Person Be? by Sheila Heti (2012): My second from Heti, after Motherhood; both landed with me because they nail aspects of my state of mind. Heti writes autofiction about writers dithering about their purpose in life. Here Sheila is working in a hair salon while trying to finish her play – some absurdist dialogue is set out in script form – and hanging out with artists like her best friend Margaux. The sex scenes are gratuitous and kinda gross. In general, I alternated between sniggering (especially at the ugly painting competition) and feeling seen: Sheila expects fate to decide things for her; God forbid she should ever have to make an actual choice. Heti is self-deprecating about an admittedly self-indulgent approach, and so funny on topics like mansplaining. This was longlisted for the Women’s Prize in 2013. (Little Free Library)

How Should a Person Be? by Sheila Heti (2012): My second from Heti, after Motherhood; both landed with me because they nail aspects of my state of mind. Heti writes autofiction about writers dithering about their purpose in life. Here Sheila is working in a hair salon while trying to finish her play – some absurdist dialogue is set out in script form – and hanging out with artists like her best friend Margaux. The sex scenes are gratuitous and kinda gross. In general, I alternated between sniggering (especially at the ugly painting competition) and feeling seen: Sheila expects fate to decide things for her; God forbid she should ever have to make an actual choice. Heti is self-deprecating about an admittedly self-indulgent approach, and so funny on topics like mansplaining. This was longlisted for the Women’s Prize in 2013. (Little Free Library)

The Light Years by Elizabeth Jane Howard (1990): The first volume of The Cazalet Chronicles, read for a book club meeting last January. I could hardly believe the publication date; it’s such a detailed, convincing picture of daily life in 1937–8 for a large, wealthy family in London and Sussex that it seems it must have been written in the 1940s. The retrospective angle, however, allows for subtle commentary on how limited women’s lives were, locked in by marriage and pregnancies. Sexual abuse is also calmly reported. One character is a lesbian, but everyone believes her partner is just a friend. The cousins’ childhood japes are especially enjoyable. And, of course, war is approaching. It’s all very Downton Abbey. I launched straight into the second book afterwards, but stalled 60 pages in. I’ll aim to get back into the series later this year. (Free mall bookshop)

The Light Years by Elizabeth Jane Howard (1990): The first volume of The Cazalet Chronicles, read for a book club meeting last January. I could hardly believe the publication date; it’s such a detailed, convincing picture of daily life in 1937–8 for a large, wealthy family in London and Sussex that it seems it must have been written in the 1940s. The retrospective angle, however, allows for subtle commentary on how limited women’s lives were, locked in by marriage and pregnancies. Sexual abuse is also calmly reported. One character is a lesbian, but everyone believes her partner is just a friend. The cousins’ childhood japes are especially enjoyable. And, of course, war is approaching. It’s all very Downton Abbey. I launched straight into the second book afterwards, but stalled 60 pages in. I’ll aim to get back into the series later this year. (Free mall bookshop)

Nonfiction

Keeper: Living with Nancy—A journey into Alzheimer’s by Andrea Gillies (2009): The inaugural Wellcome Book Prize winner. The Prize expanded in focus over a decade; I don’t think a straightforward family memoir like this would have won later on. Gillies’ family relocated to remote northern Scotland and her elderly mother- and father-in-law, Nancy and Morris, moved in. Morris was passive, with limited mobility; Nancy was confused and cantankerous, often treating Gillies like a servant. (“There’s emptiness behind her eyes, something missing that used to be there. It’s sinister.”) She’d try to keep her cool but often got frustrated and contradicted her mother-in-law’s delusions. Gillies relays facts about Alzheimer’s that I knew from In Pursuit of Memory. What has remained with me is a sense of just how gruelling the caring life is. Gillies could barely get any writing done because if she turned her back Nancy might start walking to town, or – the single most horrific incident that has stuck in my mind – place faeces on the bookshelf. (Secondhand purchase)

Keeper: Living with Nancy—A journey into Alzheimer’s by Andrea Gillies (2009): The inaugural Wellcome Book Prize winner. The Prize expanded in focus over a decade; I don’t think a straightforward family memoir like this would have won later on. Gillies’ family relocated to remote northern Scotland and her elderly mother- and father-in-law, Nancy and Morris, moved in. Morris was passive, with limited mobility; Nancy was confused and cantankerous, often treating Gillies like a servant. (“There’s emptiness behind her eyes, something missing that used to be there. It’s sinister.”) She’d try to keep her cool but often got frustrated and contradicted her mother-in-law’s delusions. Gillies relays facts about Alzheimer’s that I knew from In Pursuit of Memory. What has remained with me is a sense of just how gruelling the caring life is. Gillies could barely get any writing done because if she turned her back Nancy might start walking to town, or – the single most horrific incident that has stuck in my mind – place faeces on the bookshelf. (Secondhand purchase)

Reflections from the North Country by Sigurd F. Olson (1976): Olson was a well-known environmental writer in his time, also serving as president of the National Parks Association. Somehow I hadn’t heard of him before my husband picked this out at random. Part of a Minnesota Heritage Book series, this collection of passionate, philosophically oriented essays about the state of nature places him in the vein of Aldo Leopold – before-their-time conservationists. He ponders solitude, wilderness and human nature, asking what is primal in us and what is due to unfortunate later developments. His counsel includes simplicity and wonder rather than exploitation and waste. The chief worry that comes across is that people are now so cut off from nature they can’t see what they’re missing – and destroying. It can be depressing to read such profound 1970s works; had we heeded environmental prophets like Olson, we could have changed course before it was too late. (Free from The Book Thing of Baltimore)

Reflections from the North Country by Sigurd F. Olson (1976): Olson was a well-known environmental writer in his time, also serving as president of the National Parks Association. Somehow I hadn’t heard of him before my husband picked this out at random. Part of a Minnesota Heritage Book series, this collection of passionate, philosophically oriented essays about the state of nature places him in the vein of Aldo Leopold – before-their-time conservationists. He ponders solitude, wilderness and human nature, asking what is primal in us and what is due to unfortunate later developments. His counsel includes simplicity and wonder rather than exploitation and waste. The chief worry that comes across is that people are now so cut off from nature they can’t see what they’re missing – and destroying. It can be depressing to read such profound 1970s works; had we heeded environmental prophets like Olson, we could have changed course before it was too late. (Free from The Book Thing of Baltimore)

Educating Alice: Adventures of a Curious Woman by Alice Steinbach (2004): I’d loved her earlier travel book Without Reservations. Here she sets off on a journey of discovery and lifelong learning. I included the first essay, about enrolling in cooking lessons in Paris, in my foodie 20 Books of Summer 2020. In other chapters she takes dance lessons in Kyoto, appreciates art in Florence and Havana, walks in Jane Austen’s footsteps in Winchester and environs, studies garden design in Provence, takes a creative writing workshop in Prague, and trains Border collies in Scotland. It’s clear she loves meeting new people and chatting – great qualities in a journalist. By this time she had quit her job with the Baltimore Sun so was free to explore and make her life what she wanted. She thinks back to childhood memories of her Scottish grandmother, and imagines how she’d describe her adventures to her gentleman friend, Naohiro. She recreates everything in a way that makes this as fluent as any novel, such that I’d even dare recommend it to fiction-only readers. (Free mall bookshop)

Educating Alice: Adventures of a Curious Woman by Alice Steinbach (2004): I’d loved her earlier travel book Without Reservations. Here she sets off on a journey of discovery and lifelong learning. I included the first essay, about enrolling in cooking lessons in Paris, in my foodie 20 Books of Summer 2020. In other chapters she takes dance lessons in Kyoto, appreciates art in Florence and Havana, walks in Jane Austen’s footsteps in Winchester and environs, studies garden design in Provence, takes a creative writing workshop in Prague, and trains Border collies in Scotland. It’s clear she loves meeting new people and chatting – great qualities in a journalist. By this time she had quit her job with the Baltimore Sun so was free to explore and make her life what she wanted. She thinks back to childhood memories of her Scottish grandmother, and imagines how she’d describe her adventures to her gentleman friend, Naohiro. She recreates everything in a way that makes this as fluent as any novel, such that I’d even dare recommend it to fiction-only readers. (Free mall bookshop)

Kings of the Yukon: An Alaskan River Journey by Adam Weymouth (2018): I didn’t get the chance to read this when it was shortlisted for, and then won, the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award, but I received a copy from my wish list for Christmas that year. Alaska is a place that attracts outsiders and nonconformists. During the summer of 2016, Weymouth undertook a voyage by canoe down the nearly 2,000 miles of the Yukon River – the same epic journey made by king/Chinook salmon. He camps alongside the river bank in a tent, often with his partner, Ulli. He also visits a fish farm, meets reality TV stars and native Yup’ik people, and eats plenty of salmon. “I do occasionally consider the ethics of investigating a fish’s decline whilst stuffing my face with it.” Charting the effects of climate change without forcing the issue, he paints a somewhat bleak picture. But his descriptive writing is so lyrical, and his scenes and dialogue so natural, that he kept me eagerly riding along in the canoe with him. (Secondhand copy, gifted)

Kings of the Yukon: An Alaskan River Journey by Adam Weymouth (2018): I didn’t get the chance to read this when it was shortlisted for, and then won, the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award, but I received a copy from my wish list for Christmas that year. Alaska is a place that attracts outsiders and nonconformists. During the summer of 2016, Weymouth undertook a voyage by canoe down the nearly 2,000 miles of the Yukon River – the same epic journey made by king/Chinook salmon. He camps alongside the river bank in a tent, often with his partner, Ulli. He also visits a fish farm, meets reality TV stars and native Yup’ik people, and eats plenty of salmon. “I do occasionally consider the ethics of investigating a fish’s decline whilst stuffing my face with it.” Charting the effects of climate change without forcing the issue, he paints a somewhat bleak picture. But his descriptive writing is so lyrical, and his scenes and dialogue so natural, that he kept me eagerly riding along in the canoe with him. (Secondhand copy, gifted)

Would you be interested in reading one or more of these?

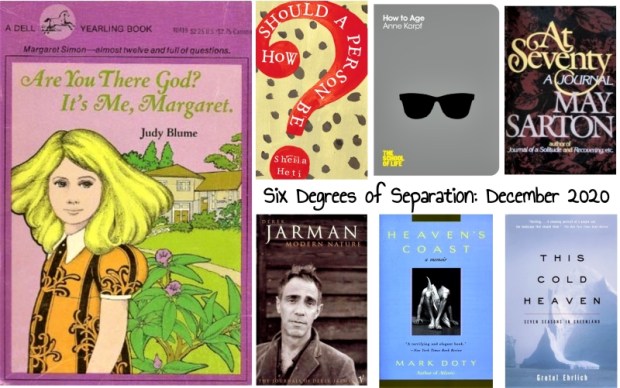

Six Degrees of Separation: From Margaret to This Cold Heaven

This month we’re starting with Are You There, God? It’s Me, Margaret (which I have punctuated appropriately!). See Kate’s opening post. I know I read this as a child, but other Judy Blume novels were more meaningful for me since I was a tomboy and late bloomer. The only line that stays with me is the chant “We must, we must, we must increase our bust!”

#1 Another book with a question in the title (and dominating the cover) is How Should a Person Be? by Sheila Heti. I found a hardback copy in the unofficial Little Free Library I ran in our neighborhood during the first lockdown before the public library reopened. Heti is a divisive author, but I loved Motherhood for perfectly encapsulating my situation. I think this one, too, is autofiction, and the title question is one I ask myself variations on frequently.

#1 Another book with a question in the title (and dominating the cover) is How Should a Person Be? by Sheila Heti. I found a hardback copy in the unofficial Little Free Library I ran in our neighborhood during the first lockdown before the public library reopened. Heti is a divisive author, but I loved Motherhood for perfectly encapsulating my situation. I think this one, too, is autofiction, and the title question is one I ask myself variations on frequently.

#2 I’ve read quite a few “How to” books, whether straightforward explanatory/self-help texts or not. Lots happened to be from the School of Life series. One I found particularly enjoyable and helpful was How to Age by Anne Karpf. She writes frankly about bodily degeneration, the pursuit of wisdom, and preparation for death. “Growth and psychological development aren’t a property of our earliest years but can continue throughout the life cycle.”

#2 I’ve read quite a few “How to” books, whether straightforward explanatory/self-help texts or not. Lots happened to be from the School of Life series. One I found particularly enjoyable and helpful was How to Age by Anne Karpf. She writes frankly about bodily degeneration, the pursuit of wisdom, and preparation for death. “Growth and psychological development aren’t a property of our earliest years but can continue throughout the life cycle.”

#3 Ageing is a major element in May Sarton’s journals, particularly as she moves from her seventies into her eighties and fights illnesses. I’ve read all but one of her autobiographical works now, and – while my favorite is Journal of a Solitude – the one I’ve chosen as most representative of her usual themes, including inspiration, camaraderie, the pressures of the writing life, and old age, is At Seventy.

#3 Ageing is a major element in May Sarton’s journals, particularly as she moves from her seventies into her eighties and fights illnesses. I’ve read all but one of her autobiographical works now, and – while my favorite is Journal of a Solitude – the one I’ve chosen as most representative of her usual themes, including inspiration, camaraderie, the pressures of the writing life, and old age, is At Seventy.

#4 Sarton was a keen gardener, as was Derek Jarman. I learned about him in the context of nature helping people come to terms with their mortality. Modern Nature reproduces the journal the gay, HIV-positive filmmaker kept in 1989–90. Prospect Cottage in Dungeness, Kent, and the unusual garden he cultivated there, was his refuge between trips to London and further afield, and a mental sanctuary when he was marooned in the hospital.

#4 Sarton was a keen gardener, as was Derek Jarman. I learned about him in the context of nature helping people come to terms with their mortality. Modern Nature reproduces the journal the gay, HIV-positive filmmaker kept in 1989–90. Prospect Cottage in Dungeness, Kent, and the unusual garden he cultivated there, was his refuge between trips to London and further afield, and a mental sanctuary when he was marooned in the hospital.

#5 One of the first memoirs I ever read and loved was Heaven’s Coast by Mark Doty, about his partner Wally’s death from AIDS. This sparked my continuing interest in illness and bereavement narratives, and it was through following up Doty’s memoirs with his collections of poems that I first got into contemporary poetry, so he’s had a major influence on my taste. I’ve had Heaven’s Coast on my rereading shelf for ages, so really must get to it in 2021.

#5 One of the first memoirs I ever read and loved was Heaven’s Coast by Mark Doty, about his partner Wally’s death from AIDS. This sparked my continuing interest in illness and bereavement narratives, and it was through following up Doty’s memoirs with his collections of poems that I first got into contemporary poetry, so he’s had a major influence on my taste. I’ve had Heaven’s Coast on my rereading shelf for ages, so really must get to it in 2021.

#6 Thinking of heaven, a nice loop back to Blume’s Margaret and her determination to find God … one of the finest travel books I’ve read is This Cold Heaven, about Gretel Ehrlich’s expeditions to Greenland and historical precursors who explored it. Even more than her intrepid wanderings, I was impressed by her prose, which made the icy scenery new every time. “Part jewel, part eye, part lighthouse, part recumbent monolith, the ice is a bright spot on the upper tier of the globe where the world’s purse strings have been pulled tight.”

#6 Thinking of heaven, a nice loop back to Blume’s Margaret and her determination to find God … one of the finest travel books I’ve read is This Cold Heaven, about Gretel Ehrlich’s expeditions to Greenland and historical precursors who explored it. Even more than her intrepid wanderings, I was impressed by her prose, which made the icy scenery new every time. “Part jewel, part eye, part lighthouse, part recumbent monolith, the ice is a bright spot on the upper tier of the globe where the world’s purse strings have been pulled tight.”

A fitting final selection for this week’s properly chilly winter temperatures, too. I’ll be writing up my first snowy and/or holiday-themed reads of the year in a couple of weeks.

Join us for #6Degrees of Separation if you haven’t already! (Hosted on the first Saturday of each month by Kate W. of Books Are My Favourite and Best.)

Have you read any of my selections? Are you tempted by any you didn’t know before?

20 Books of Summer #4 + Substitutes & Plane Reading

You’ll have to excuse me posting twice in one day. I’ve just finished packing the last few things for my three weeks in America, and want to get my latest #20BooksofSummer review out there before I fly early tomorrow. What with a layover in Toronto, it will be a very long day of travel, so I think the volume of reading material I’m taking is justified! (See the last photo of the post.)

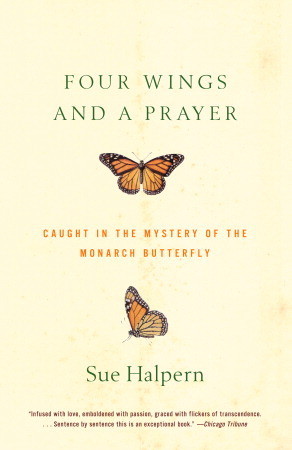

Four Wings and a Prayer: Caught in the Mystery of the Monarch Butterfly by Sue Halpern (2001)

I admire nonfiction books that successfully combine lots of genres into a dynamic narrative. This one incorporates travel, science, memoir, history, and even politics. Halpern spent a year tracking monarch butterflies on their biannual continent-wide migrations, which were still not well understood at that point. She rides through Texas into Mexico with Bill Calvert, field researcher extraordinaire; goes gliding with David Gibo, a university biologist, in fields near Toronto; and hears from scientists and laymen alike about the monarchs’ habits and outlook. It happened to be a worryingly poor year for the butterflies, yet citizen science initiatives provided valuable information that could be used to predict their future.

I admire nonfiction books that successfully combine lots of genres into a dynamic narrative. This one incorporates travel, science, memoir, history, and even politics. Halpern spent a year tracking monarch butterflies on their biannual continent-wide migrations, which were still not well understood at that point. She rides through Texas into Mexico with Bill Calvert, field researcher extraordinaire; goes gliding with David Gibo, a university biologist, in fields near Toronto; and hears from scientists and laymen alike about the monarchs’ habits and outlook. It happened to be a worryingly poor year for the butterflies, yet citizen science initiatives provided valuable information that could be used to predict their future.

The book is especially insightful about clashes between environmentalist initiatives and local livelihoods in Mexico (tree huggers versus subsistence loggers) and the joy of doing practical science with simple tools you make yourself. It’s also about how focused attention becomes passion. “Science, like belief, starts with wonder, and wonder starts with a question,” Halpern writes.

The style is engaging, though at nearly 20 years old the book feels a bit dated, and I might have liked more personal reflections than interviews with (middle-aged, white, male) scientists. I only realized on the very last page, through the acknowledgments, that the author is married to Bill McKibben, a respected environment writer. [She frequently mentions Fred Urquhart, a Toronto zoology professor; I wondered if he could be related to Jane Urquhart, a Canadian novelist whose novel Sanctuary Line features monarchs. (Turns out: no relation. Oh well!)]

Readalikes: Farther Away by Jonathan Franzen & Ruins by Peter Kuper

My rating:

I’ve already done some substituting on my 20 Books of Summer. I decided against reading Vendela Vida’s Girls on the Verge after perusing the table of contents and the first few pages and gauging reader opinions on Goodreads. I have a couple of review books, Twister by Genanne Walsh and The Life and Loves of Lena Gaunt by Tracy Farr, that I’m enjoying but will have to leave behind while I’m in the States, so I may need that little extra push to finish them once I get back. I’ve also been rereading a favorite, Paulette Bates Alden’s memoir Crossing the Moon, which has proved an excellent follow-up to Sheila Heti’s Motherhood.

(What I haven’t determined yet is which books these will be standing in for.) Waiting in the wings in case further substitutions are needed is this stack of review books:

Also from the #20Books list and coming with me on the flight are Madeleine L’Engle’s The Summer of the Great-Grandmother and Janet Fitch’s White Oleander, which are both terrific thus far. The final print book joining me for the journey is Transit by Rachel Cusk. I have attempted to read her twice before and failed to get through a whole book, so we’ll see if it’s third time lucky. It seems like the perfect book to read in transit to Canada, after all.

Finally, in progress on the Kindle are Summer by Karl Ove Knausgaard, the last in his set of four seasonal essay collections, and The Late Bloomers’ Club by Louise Miller, another cozy novel set in fictional Guthrie, Vermont, which she introduced in her previous book, The City Baker’s Guide to Country Living.

It’ll be a busy few weeks helping my parents pack up their house and moving my mom into her new place, plus doing a reduced freelance work load for the final two weeks. It’s also going to be a strange time because I have to say goodbye to a house that’s been a part of my life for 13 years, and sort through box after box of mementoes before putting everything into medium-term storage.

I won’t be online all that much, and can’t promise to keep up with everyone else’s blogs, but I’ll try to pop in with a few reviews.

Happy July reading!

How Not to Decide: Motherhood by Sheila Heti

Should one have children? No matter who’s asking the question or in what context, you’re going to get the whole gamut of replies, as proven by this recent Literary Hub survey of authors. Should I have children? Turn the question personal and, even if it’s actually rhetorical, you’ll still get an opinion from every quarter. As The Decision looms over her, the narrator of Sheila Heti’s new novel, a 37-year-old writer from Toronto, isn’t sure who to listen to. Her neurotic inner voice makes her second-guess her life. “The question of a child is a bug in the brain—it’s a bug that crawls across everything, every memory, and every sense of my own future.” Meanwhile, acquaintances and strangers alike all have their two cents to chip in. Everywhere she goes on her book tour, for instance, she hears other people’s stories and has to sift through them. She’s something like the protagonist of Rachel Cusk’s Outline trilogy, though with a stronger personality and internal commentary.

Having a child is an act of creation, and Heti’s narrator worries that she only has sufficient creative energy for one or the other: writing or breeding. Her identity as an artist is so precious to her that she is terrified of giving it up, or watering it down, to risk being a (not very good?) mother. Yet she has the sense that to remain childless she had better come up with a really good excuse. People will want to know what she is going to do with her life instead, and they’re unlikely to be satisfied by the notion that her books are like her babies.

The novel is in short, aphoristic paragraphs and is dominated by cogitation rather than scenes, though there are some concrete events and secondary characters, such as the narrator’s mother; her friend Libby, a new mother; and her partner, Miles, who has a 12-year-old daughter from a previous relationship. The sections are given headings like “PMS,” “Bleeding,” “Follicular,” and “Ovulating,” which suggest the cyclical nature of life: whether she likes it or not, this character is part of a physical process geared towards reproduction.

The cyclical workings of the female body mirror the circularity of her thoughts: she keeps revolving around the same questions, never seeming to get any closer to a decision – though by the end she does decide. The temptation is always to offload the choice onto an external, fate-like force. The narrator wants the oracular voice of the universe to answer everything for her via coin tosses. (Heti writes in a prefatory note that these were based on actual coin tosses.) She asks series of yes/no questions and reports what the coins have to say. It’s a way of avoiding responsibility for her own decision, and produces some truly hilarious passages. Oh, the absurdity of having a dialogue with an impersonal force!

Our heroine does ultimately realize how random and meaningless the coins’ yes/no answers are, but she continues to look outside herself for wisdom: to a fortune teller, psychics, dreams, and even a crazy woman in New York City who hits her up for money. Anything to bypass the wringer of her own mind. She also latches onto the biblical story of Jacob wrestling with the angel, and contrasts this with the symbol of a kitchen knife, which represents a demon that robs her of hope.

Every woman is a daughter as well as a potential mother, and a particularly moving strand of Motherhood is the narrator’s relationship with her female ancestors. Her Hungarian grandmother, Magda, survived Auschwitz only to die of cancer at 53; her mother, a doctor, devoted herself to her career and left the traditional household and childrearing tasks to her husband. This dual legacy of suffering and professional pride helps explain the narrator’s feelings. Deep down, she believes her family line was meant to end in a concentration camp; how dare she continue it now? She also emulates her mother’s commitment to a cerebral vocation – “So I also wanted to be the brains: to be nothing but words on a page.”

Every woman is a daughter as well as a potential mother, and a particularly moving strand of Motherhood is the narrator’s relationship with her female ancestors. Her Hungarian grandmother, Magda, survived Auschwitz only to die of cancer at 53; her mother, a doctor, devoted herself to her career and left the traditional household and childrearing tasks to her husband. This dual legacy of suffering and professional pride helps explain the narrator’s feelings. Deep down, she believes her family line was meant to end in a concentration camp; how dare she continue it now? She also emulates her mother’s commitment to a cerebral vocation – “So I also wanted to be the brains: to be nothing but words on a page.”

Chance, inheritance, and choice vie for pride of place in this relentless, audacious inquiry into the purpose of a woman’s life. I marked out dozens of quotes that could have been downloaded directly from my head or copied from my e-mails and journal pages. The book encapsulates nearly every thought that has gone through my mind over the last decade as I’ve faced the intractable question of whether to have children. I suspect it will mean the most to people who are still unsure or have already decided against children; parents may interpret Heti’s arguments as personal barbs, even though the narrator insists her own decision is not an inherent comment on anyone else’s. It’s a book I could have written, but now don’t have to; Heti has captured brilliantly what it’s like to be in this situation in this moment in time.

Here are a few of my favorite passages. They should give you an idea of whether this book might resonate with you, or at least interest you academically:

“On the one hand, the joy of children. On the other hand, the misery of them. On the one hand, the freedom of not having children. On the other hand, the loss of never having had them—but what is there to lose?”

“for a woman of curiosity, no decision will ever feel like the right one. In both, too much is missing. What can I say, except: I forgive myself for every time I neglected to take a risk, for all the narrowings and winnowings of my life. I understand that fear beckons to a person as much as possibility does, and even more strongly.”

“I don’t have to live every possible life, or to experience that particular love. I know I cannot hide from life; that life will give me experiences no matter what I choose. Not having a child is no escape from life, for life will always put me in situations, and show me new things, and take me to darknesses I wouldn’t choose to see, and all sorts of treasures of knowledge I cannot comprehend.”

My rating:

Motherhood was published in the UK by Harvill Secker on May 24th. My thanks to the publisher for the free copy for review. It came out in North America on May 1st (Knopf Canada / Henry Holt and Co.).

Merritt asked about the novel’s magic realist element and how stylistically different his novels have been from each other. He was glad she found the book funny, as “life is tragicomic.” In an effort not to get stuck in a rut, he deliberately ‘breaks the mould’ after each book and starts over. This has not made him popular with his publisher!

Merritt asked about the novel’s magic realist element and how stylistically different his novels have been from each other. He was glad she found the book funny, as “life is tragicomic.” In an effort not to get stuck in a rut, he deliberately ‘breaks the mould’ after each book and starts over. This has not made him popular with his publisher!

Last year’s Dylan Thomas Prize winner interviewed this year’s winner, and it was clear that the mutual admiration was strong. Though I had mixed feelings about Luster (

Last year’s Dylan Thomas Prize winner interviewed this year’s winner, and it was clear that the mutual admiration was strong. Though I had mixed feelings about Luster (

Shipstead (also a Dylan Thomas Prize winner) echoed something Leilani had said: that she starts a novel with questions, not answers. Such humility is refreshing, and a sure way to avoid being preachy in fiction. Her new novel, Great Circle, is among my

Shipstead (also a Dylan Thomas Prize winner) echoed something Leilani had said: that she starts a novel with questions, not answers. Such humility is refreshing, and a sure way to avoid being preachy in fiction. Her new novel, Great Circle, is among my

Lockwood is the only novelist to be included on the Atlantic’s roster of best tweets. She and Nina Stibbe, who interviewed her, agreed that 1) things aren’t funny when they try too hard and 2) the Internet used to be a taboo subject for fiction – producing time-stamped references that editors used to remove. “I had so many observations and I didn’t know where to put them,” Lockwood said, and it seems to her perverse to not write about something that is such a major part of our daily lives. The title of her Women’s Prize-shortlisted novel, No One Is Talking About This (

Lockwood is the only novelist to be included on the Atlantic’s roster of best tweets. She and Nina Stibbe, who interviewed her, agreed that 1) things aren’t funny when they try too hard and 2) the Internet used to be a taboo subject for fiction – producing time-stamped references that editors used to remove. “I had so many observations and I didn’t know where to put them,” Lockwood said, and it seems to her perverse to not write about something that is such a major part of our daily lives. The title of her Women’s Prize-shortlisted novel, No One Is Talking About This (

Like Lockwood, Pachico was part of the “10 @ 10” series featuring debut novelists (though her first book, the linked story collection

Like Lockwood, Pachico was part of the “10 @ 10” series featuring debut novelists (though her first book, the linked story collection

Speaking to Arifa Akbar about

Speaking to Arifa Akbar about

I’ve read more of and gotten on better with Heti’s work than Cusk’s, so this was a rare case of being perhaps more interested in interviewer than interviewee. Heti said that, compared with the Outline trilogy, Cusk’s new novel Second Place feels wilder and more instinctual. Cusk, speaking from the Greek island of Tinos, where she is researching marble quarrying, described her book in often vague yet overall intriguing terms: it’s about exile and the illicit, she said; about femininity and entitlement to speak; about the domestic space and how things are legitimized; about the adoption of male values and the “rightness of the artist.”

I’ve read more of and gotten on better with Heti’s work than Cusk’s, so this was a rare case of being perhaps more interested in interviewer than interviewee. Heti said that, compared with the Outline trilogy, Cusk’s new novel Second Place feels wilder and more instinctual. Cusk, speaking from the Greek island of Tinos, where she is researching marble quarrying, described her book in often vague yet overall intriguing terms: it’s about exile and the illicit, she said; about femininity and entitlement to speak; about the domestic space and how things are legitimized; about the adoption of male values and the “rightness of the artist.”

Orchid & the Wasp by Caoilinn Hughes: From the Iraq War protests to the Occupy movement in New York City, we follow antiheroine Gael Foess as she tries to get her brother’s art recognized. This debut novel is a potent reminder that money and skills don’t get distributed fairly in this life.

Orchid & the Wasp by Caoilinn Hughes: From the Iraq War protests to the Occupy movement in New York City, we follow antiheroine Gael Foess as she tries to get her brother’s art recognized. This debut novel is a potent reminder that money and skills don’t get distributed fairly in this life. Bitter Orange by Claire Fuller: Fuller’s third novel tells the suspenseful story of the profligate summer of 1969 spent at a dilapidated English country house. The characters and atmosphere are top-notch; this is an absorbing, satisfying novel to swallow down in big gulps.

Bitter Orange by Claire Fuller: Fuller’s third novel tells the suspenseful story of the profligate summer of 1969 spent at a dilapidated English country house. The characters and atmosphere are top-notch; this is an absorbing, satisfying novel to swallow down in big gulps. The Only Story by Julian Barnes: It may be a familiar story – a May–December romance that fizzles out – but, as Paul believes, we only really get one love story, the defining story of our lives. The picture of romantic youth shading into cynical but still hopeful middle age really resonates, as do the themes of unconventionality, memory, addiction and pity.

The Only Story by Julian Barnes: It may be a familiar story – a May–December romance that fizzles out – but, as Paul believes, we only really get one love story, the defining story of our lives. The picture of romantic youth shading into cynical but still hopeful middle age really resonates, as do the themes of unconventionality, memory, addiction and pity. The Immortalists by Chloe Benjamin: Summer 1969: four young siblings escape a sweltering New York City morning by visiting a fortune teller who can tell you the day you’ll die; in the decades that follow, they have to decide what to do with this advance knowledge: will it spur them to live courageous lives, or drive them to desperation? This compelling family story lives up to the hype.

The Immortalists by Chloe Benjamin: Summer 1969: four young siblings escape a sweltering New York City morning by visiting a fortune teller who can tell you the day you’ll die; in the decades that follow, they have to decide what to do with this advance knowledge: will it spur them to live courageous lives, or drive them to desperation? This compelling family story lives up to the hype. An American Marriage by Tayari Jones: Roy and Celestial only get a year of happy marriage before he’s falsely accused of rape and sentenced to 12 years in prison in Louisiana. This would make a great book club pick: I ached for all the main characters in their impossible situation; there’s a lot to probe about their personalities and motivations, and about how they reveal or disguise themselves through their narration and letters.

An American Marriage by Tayari Jones: Roy and Celestial only get a year of happy marriage before he’s falsely accused of rape and sentenced to 12 years in prison in Louisiana. This would make a great book club pick: I ached for all the main characters in their impossible situation; there’s a lot to probe about their personalities and motivations, and about how they reveal or disguise themselves through their narration and letters. The Italian Teacher by Tom Rachman: Charles “Pinch” Bavinsky is an Italian teacher; as a boy in Rome in the 1950s–60s he believed he’d follow in the footsteps of his sculptor mother and his moderately famous father, Bear Bavinsky, who paints close-ups of body parts, but along the way something went wrong. This is a rewarding novel about the desperation to please, or perhaps exceed, one’s parents and the legacy of artists in a fickle market.

The Italian Teacher by Tom Rachman: Charles “Pinch” Bavinsky is an Italian teacher; as a boy in Rome in the 1950s–60s he believed he’d follow in the footsteps of his sculptor mother and his moderately famous father, Bear Bavinsky, who paints close-ups of body parts, but along the way something went wrong. This is a rewarding novel about the desperation to please, or perhaps exceed, one’s parents and the legacy of artists in a fickle market. The Incendiaries by R. O. Kwon: A sophisticated, unsettling debut novel about faith and its aftermath, fractured through the experience of three people coming to terms with painful circumstances. Kwon spent 10 years writing this book, and that time and diligence come through in how carefully honed the prose is: such precise images; not a single excess word.

The Incendiaries by R. O. Kwon: A sophisticated, unsettling debut novel about faith and its aftermath, fractured through the experience of three people coming to terms with painful circumstances. Kwon spent 10 years writing this book, and that time and diligence come through in how carefully honed the prose is: such precise images; not a single excess word. Unsheltered by Barbara Kingsolver: Kingsolver’s bold eighth novel has a dual timeline that compares the America of the 1870s and the recent past and finds that they are linked by distrust and displacement. There’s so much going on that it feels like it encompasses all of human life; it’s by no means a subtle book, but it’s an important one for our time, with many issues worth pondering and discussing.

Unsheltered by Barbara Kingsolver: Kingsolver’s bold eighth novel has a dual timeline that compares the America of the 1870s and the recent past and finds that they are linked by distrust and displacement. There’s so much going on that it feels like it encompasses all of human life; it’s by no means a subtle book, but it’s an important one for our time, with many issues worth pondering and discussing. Southernmost by Silas House: In House’s sixth novel, a Tennessee preacher’s family life falls apart when he accepts a gay couple into his church. We go on a long journey with Asher Sharp: not just a literal road trip from Tennessee to Florida, but also a spiritual passage from judgment to grace in this beautiful, quietly moving novel of redemption and openness to what life might teach us.

Southernmost by Silas House: In House’s sixth novel, a Tennessee preacher’s family life falls apart when he accepts a gay couple into his church. We go on a long journey with Asher Sharp: not just a literal road trip from Tennessee to Florida, but also a spiritual passage from judgment to grace in this beautiful, quietly moving novel of redemption and openness to what life might teach us. Little by Edward Carey: This is a deliciously macabre, Dickensian novel about Madame Tussaud, who started life as Anne Marie Grosholtz in Switzerland in 1761. From a former monkey house to the Versailles palace and back, Marie must tread carefully as the French Revolution advances and a desire for wax heads is replaced by that for decapitated ones.

Little by Edward Carey: This is a deliciously macabre, Dickensian novel about Madame Tussaud, who started life as Anne Marie Grosholtz in Switzerland in 1761. From a former monkey house to the Versailles palace and back, Marie must tread carefully as the French Revolution advances and a desire for wax heads is replaced by that for decapitated ones. Motherhood by Sheila Heti: Chance, inheritance, and choice vie for pride of place in this relentless, audacious inquiry into the purpose of a woman’s life. The book encapsulates nearly every thought that has gone through my mind over the last decade as I’ve faced the intractable question of whether to have children.

Motherhood by Sheila Heti: Chance, inheritance, and choice vie for pride of place in this relentless, audacious inquiry into the purpose of a woman’s life. The book encapsulates nearly every thought that has gone through my mind over the last decade as I’ve faced the intractable question of whether to have children. Florida by Lauren Groff: There’s an oppressive atmosphere throughout these 11 short stories, with violent storms reminding the characters of an uncaring universe, falling-apart relationships, and the threat of environmental catastrophe. Florida feels innovative and terrifyingly relevant; any one of its stories is a bracing read; together they form a masterpiece. (I never would have predicted that a short story collection would be my favorite fiction read of the year!)

Florida by Lauren Groff: There’s an oppressive atmosphere throughout these 11 short stories, with violent storms reminding the characters of an uncaring universe, falling-apart relationships, and the threat of environmental catastrophe. Florida feels innovative and terrifyingly relevant; any one of its stories is a bracing read; together they form a masterpiece. (I never would have predicted that a short story collection would be my favorite fiction read of the year!)

Three Poems by Hannah Sullivan: These poem-essays give fragmentary images of city life and question the notion of progress and what meaning a life leaves behind. “The Sandpit after Rain” stylishly but grimly juxtaposes her father’s death and her son’s birth.

Three Poems by Hannah Sullivan: These poem-essays give fragmentary images of city life and question the notion of progress and what meaning a life leaves behind. “The Sandpit after Rain” stylishly but grimly juxtaposes her father’s death and her son’s birth. Comfort Measures Only: New and Selected Poems, 1994–2016 by Rafael Campo: Superb, poignant poetry about illness and the physician’s duty. A good bit of this was composed in response to the AIDS crisis; it’s remarkable how Campo wrings beauty out of clinical terminology and tragic situations.

Comfort Measures Only: New and Selected Poems, 1994–2016 by Rafael Campo: Superb, poignant poetry about illness and the physician’s duty. A good bit of this was composed in response to the AIDS crisis; it’s remarkable how Campo wrings beauty out of clinical terminology and tragic situations. The Small Door of Your Death by Sheryl St. Germain: St. Germain’s seventh collection is in memory of her son Gray, who died of a drug overdose in 2014, aged 30. She turns her family history of alcohol and drug use into a touchpoint and affirms life’s sensual pleasures – everything from the smell of brand-new cowboy boots to luscious fruits.

The Small Door of Your Death by Sheryl St. Germain: St. Germain’s seventh collection is in memory of her son Gray, who died of a drug overdose in 2014, aged 30. She turns her family history of alcohol and drug use into a touchpoint and affirms life’s sensual pleasures – everything from the smell of brand-new cowboy boots to luscious fruits. I first read this nearly four years ago (you can find my initial review in an

I first read this nearly four years ago (you can find my initial review in an

I mostly know Colwin as a food writer, but she also published fiction. This subtle story collection turns on quiet, mostly domestic dramas: people falling in and out of love, stepping out on their spouses and trying to protect their families. I didn’t particularly engage with the central two stories about cousins Vincent and Guido (characters from her novel Happy All the Time, which I abandoned a few years back), but the rest more than made up for them.

I mostly know Colwin as a food writer, but she also published fiction. This subtle story collection turns on quiet, mostly domestic dramas: people falling in and out of love, stepping out on their spouses and trying to protect their families. I didn’t particularly engage with the central two stories about cousins Vincent and Guido (characters from her novel Happy All the Time, which I abandoned a few years back), but the rest more than made up for them.

Like her protagonist, Sophie Caco, Danticat was raised by her aunt in Haiti and reunited with her parents in the USA at age 12. As Sophie grows up and falls in love with an older musician, she and her mother are both haunted by sexual trauma that nothing – not motherhood, not a long-awaited return to Haiti – seems to heal. I loved the descriptions of Haiti (“The sun, which was once god to my ancestors, slapped my face as though I had done something wrong. The fragrance of crushed mint leaves and stagnant pee alternated in the breeze” and “The stars fell as though the glue that held them together had come loose”), and the novel gives a powerful picture of a maternal line marred by guilt and an obsession with sexual purity. However, compared to Danticat’s later novel, Claire of the Sea Light, I found the narration a bit flat and the story interrupted – thinking particularly of the gap between ages 12 and 18 for Sophie. (Another Oprah’s Book Club selection.)

Like her protagonist, Sophie Caco, Danticat was raised by her aunt in Haiti and reunited with her parents in the USA at age 12. As Sophie grows up and falls in love with an older musician, she and her mother are both haunted by sexual trauma that nothing – not motherhood, not a long-awaited return to Haiti – seems to heal. I loved the descriptions of Haiti (“The sun, which was once god to my ancestors, slapped my face as though I had done something wrong. The fragrance of crushed mint leaves and stagnant pee alternated in the breeze” and “The stars fell as though the glue that held them together had come loose”), and the novel gives a powerful picture of a maternal line marred by guilt and an obsession with sexual purity. However, compared to Danticat’s later novel, Claire of the Sea Light, I found the narration a bit flat and the story interrupted – thinking particularly of the gap between ages 12 and 18 for Sophie. (Another Oprah’s Book Club selection.) Maybe you grew up in or near a town like Mooreland, Indiana (population 300). Born in 1965 when her brother and sister were 13 and 10, Kimmel was affectionately referred to as an “Afterthought” and nicknamed “Zippy” for her boundless energy. Gawky and stubborn, she pulled every trick in the book to try to get out of going to Quaker meetings three times a week, preferring to go fishing with her father. The short chapters, headed by family or period photos, are sets of thematic childhood anecdotes about particular neighbors, school friends and pets. I especially loved her parents: her mother reading approximately 40,000 science fiction novels while wearing a groove into the couch, and her father’s love of the woods (which he called his “church”) and elaborate preparations for camping trips an hour away.

Maybe you grew up in or near a town like Mooreland, Indiana (population 300). Born in 1965 when her brother and sister were 13 and 10, Kimmel was affectionately referred to as an “Afterthought” and nicknamed “Zippy” for her boundless energy. Gawky and stubborn, she pulled every trick in the book to try to get out of going to Quaker meetings three times a week, preferring to go fishing with her father. The short chapters, headed by family or period photos, are sets of thematic childhood anecdotes about particular neighbors, school friends and pets. I especially loved her parents: her mother reading approximately 40,000 science fiction novels while wearing a groove into the couch, and her father’s love of the woods (which he called his “church”) and elaborate preparations for camping trips an hour away. This was a breezy, delightful novel perfect for summer reading. In 1962 Natalie Marx’s family is looking for a vacation destination and sends query letters to various Vermont establishments. Their reply from the Inn at Lake Devine (proprietress: Ingrid Berry) tactfully but firmly states that the inn’s regular guests are Gentiles. In other words, no Jews allowed. The adolescent Natalie is outraged, and when the chance comes for her to infiltrate the Inn as the guest of one of her summer camp roommates, she sees it as a secret act of revenge.

This was a breezy, delightful novel perfect for summer reading. In 1962 Natalie Marx’s family is looking for a vacation destination and sends query letters to various Vermont establishments. Their reply from the Inn at Lake Devine (proprietress: Ingrid Berry) tactfully but firmly states that the inn’s regular guests are Gentiles. In other words, no Jews allowed. The adolescent Natalie is outraged, and when the chance comes for her to infiltrate the Inn as the guest of one of her summer camp roommates, she sees it as a secret act of revenge. In 1993 Steinbach, then in her fifties, took a sabbatical from her job as a Baltimore Sun journalist to travel for nine months straight in Paris, England and Italy. As a divorcee with two grown sons, she no longer felt shackled to her Maryland home and wanted to see if she could recover a more spontaneous and adventurous version of herself and not be defined exclusively by her career. Her innate curiosity and experience as a reporter helped her to quickly form relationships with other English-speaking tourists, which was an essential for someone traveling alone.

In 1993 Steinbach, then in her fifties, took a sabbatical from her job as a Baltimore Sun journalist to travel for nine months straight in Paris, England and Italy. As a divorcee with two grown sons, she no longer felt shackled to her Maryland home and wanted to see if she could recover a more spontaneous and adventurous version of herself and not be defined exclusively by her career. Her innate curiosity and experience as a reporter helped her to quickly form relationships with other English-speaking tourists, which was an essential for someone traveling alone. The Only Story by Julian Barnes: A familiar story: a May–December romance fizzles out. A sad story: an idealistic young man who swears he’ll never be old and boring has to face that this romance isn’t all he wanted it to be. A love story nonetheless. Paul met 48-year-old Susan, a married mother of two, at the local tennis club when he was 19. The narrative is partly the older Paul’s way of salvaging what happy memories he can, but also partly an extended self-defense. Barnes takes what could have been a dreary and repetitive story line and makes it an exquisitely plangent progression: first-person into second-person into third-person. The picture of romantic youth shading into cynical but still hopeful middle age really resonates, as do the themes of unconventionality, memory, addiction and pity.

The Only Story by Julian Barnes: A familiar story: a May–December romance fizzles out. A sad story: an idealistic young man who swears he’ll never be old and boring has to face that this romance isn’t all he wanted it to be. A love story nonetheless. Paul met 48-year-old Susan, a married mother of two, at the local tennis club when he was 19. The narrative is partly the older Paul’s way of salvaging what happy memories he can, but also partly an extended self-defense. Barnes takes what could have been a dreary and repetitive story line and makes it an exquisitely plangent progression: first-person into second-person into third-person. The picture of romantic youth shading into cynical but still hopeful middle age really resonates, as do the themes of unconventionality, memory, addiction and pity.

Florida by Lauren Groff: Two major, connected threads in this superb story collection are ambivalence about Florida, and ambivalence about motherhood. There’s an oppressive atmosphere throughout, with environmental catastrophe an underlying threat. Set-ups vary in scope from almost the whole span of a life to one scene. A dearth of named characters emphasizes just how universal the scenarios and emotions are. Groff’s style is like a cross between Karen Russell’s Swamplandia! and Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, and her unexpected turns of phrase jump off the page. A favorite was “Above and Below,” in which a woman slips into homelessness. Florida feels innovative and terrifyingly relevant. Any one of its stories is a bracing read; together they form a masterpiece.

Florida by Lauren Groff: Two major, connected threads in this superb story collection are ambivalence about Florida, and ambivalence about motherhood. There’s an oppressive atmosphere throughout, with environmental catastrophe an underlying threat. Set-ups vary in scope from almost the whole span of a life to one scene. A dearth of named characters emphasizes just how universal the scenarios and emotions are. Groff’s style is like a cross between Karen Russell’s Swamplandia! and Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, and her unexpected turns of phrase jump off the page. A favorite was “Above and Below,” in which a woman slips into homelessness. Florida feels innovative and terrifyingly relevant. Any one of its stories is a bracing read; together they form a masterpiece.

The Italian Teacher by Tom Rachman: Charles “Pinch” Bavinsky is just an Italian teacher, though as a boy in Rome in the 1950s–60s he believed he would follow in the footsteps of his sculptor mother and his moderately famous father, Bear Bavinsky, who paints close-ups of body parts. We follow Pinch through the rest of his life, a sad one of estrangement, loss and misunderstandings – but ultimately there’s a sly triumph in store for the boy who was told that he’d never make it as an artist. Rachman jets between lots of different places – Rome, New York City, Toronto, rural France, London – and ropes in quirky characters in the search for an identity and a place to belong. This is a rewarding story about the desperation to please, or perhaps exceed, one’s parents, and the legacy of artists in a fickle market.

The Italian Teacher by Tom Rachman: Charles “Pinch” Bavinsky is just an Italian teacher, though as a boy in Rome in the 1950s–60s he believed he would follow in the footsteps of his sculptor mother and his moderately famous father, Bear Bavinsky, who paints close-ups of body parts. We follow Pinch through the rest of his life, a sad one of estrangement, loss and misunderstandings – but ultimately there’s a sly triumph in store for the boy who was told that he’d never make it as an artist. Rachman jets between lots of different places – Rome, New York City, Toronto, rural France, London – and ropes in quirky characters in the search for an identity and a place to belong. This is a rewarding story about the desperation to please, or perhaps exceed, one’s parents, and the legacy of artists in a fickle market.

The Unmapped Mind by Christian Donlan: Some of the best medical writing from a layman’s perspective I’ve ever read. Donlan, a Brighton-area video games journalist, was diagnosed with (relapsing, remitting) multiple sclerosis in 2014. “I think sometimes that early MS is a sort of tasting menu of neurological disease,” Donlan wryly offers. He approaches his disease with good humor and curiosity, using metaphors of maps to depict himself as an explorer into uncharted territory. The accounts of going in for an MRI and a round of chemotherapy are excellent. Short interludes also give snippets from the history of MS and the science of neurology in general. What’s especially nice is how he sets up parallels with his daughter’s early years. My frontrunner for next year’s Wellcome Book Prize so far.

The Unmapped Mind by Christian Donlan: Some of the best medical writing from a layman’s perspective I’ve ever read. Donlan, a Brighton-area video games journalist, was diagnosed with (relapsing, remitting) multiple sclerosis in 2014. “I think sometimes that early MS is a sort of tasting menu of neurological disease,” Donlan wryly offers. He approaches his disease with good humor and curiosity, using metaphors of maps to depict himself as an explorer into uncharted territory. The accounts of going in for an MRI and a round of chemotherapy are excellent. Short interludes also give snippets from the history of MS and the science of neurology in general. What’s especially nice is how he sets up parallels with his daughter’s early years. My frontrunner for next year’s Wellcome Book Prize so far.

Implosion by Elizabeth W. Garber: The author grew up in a glass house designed by her father, Modernist architect Woodie Garber, outside Cincinnati in the 1960s to 70s. This and Woodie’s other most notable design, Sander Hall, a controversial tower-style dorm at the University of Cincinnati that was later destroyed in a controlled explosion, serve as powerful metaphors for her dysfunctional family life. Woodie is such a fascinating, flawed figure. Garber endured sexual and psychological abuse yet likens him to Odysseus, the tragic hero of his own life. She connected with him over Le Corbusier’s designs, but it was impossible for a man born in the 1910s to understand his daughter’s generation. This definitely is not a boring tome just for architecture buffs. It’s a masterful memoir for everyone.

Implosion by Elizabeth W. Garber: The author grew up in a glass house designed by her father, Modernist architect Woodie Garber, outside Cincinnati in the 1960s to 70s. This and Woodie’s other most notable design, Sander Hall, a controversial tower-style dorm at the University of Cincinnati that was later destroyed in a controlled explosion, serve as powerful metaphors for her dysfunctional family life. Woodie is such a fascinating, flawed figure. Garber endured sexual and psychological abuse yet likens him to Odysseus, the tragic hero of his own life. She connected with him over Le Corbusier’s designs, but it was impossible for a man born in the 1910s to understand his daughter’s generation. This definitely is not a boring tome just for architecture buffs. It’s a masterful memoir for everyone.

Bookworm by Lucy Mangan: Mangan takes us along on a nostalgic chronological tour through the books she loved most as a child and adolescent. No matter how much or how little of your early reading overlaps with hers, you’ll appreciate her picture of the intensity of children’s relationship with books – they can completely shut out the world and devour their favorite stories over and over, almost living inside them, they love and believe in them so much – and her tongue-in-cheek responses to them upon rereading them decades later. There are so many witty lines that it doesn’t really matter whether you give a fig about the particular titles she discusses or not. A delightful paean to the joys of being a lifelong reader; recommended to bibliophiles and parents trying to make bookworms out of their children.

Bookworm by Lucy Mangan: Mangan takes us along on a nostalgic chronological tour through the books she loved most as a child and adolescent. No matter how much or how little of your early reading overlaps with hers, you’ll appreciate her picture of the intensity of children’s relationship with books – they can completely shut out the world and devour their favorite stories over and over, almost living inside them, they love and believe in them so much – and her tongue-in-cheek responses to them upon rereading them decades later. There are so many witty lines that it doesn’t really matter whether you give a fig about the particular titles she discusses or not. A delightful paean to the joys of being a lifelong reader; recommended to bibliophiles and parents trying to make bookworms out of their children.