The Wellcome Book Prize 2018 Awards Ceremony

Hey, we got it right! Mark O’Connell’s To Be a Machine, our shadow panel’s pick, won the Wellcome Book Prize 2018 last night. Of the three shadow panels I’ve participated in and the many others I’ve observed, this is the only time I remember the shadow winner matching the official one. Clare, Paul and I were there in person for the announcement at the Wellcome Collection in London. When we briefly spoke to the judges’ chair, Edmund de Waal, later in the evening, he said he was “relieved” that their decision matched ours – but I think it was definitely the other way around!

Hey, we got it right! Mark O’Connell’s To Be a Machine, our shadow panel’s pick, won the Wellcome Book Prize 2018 last night. Of the three shadow panels I’ve participated in and the many others I’ve observed, this is the only time I remember the shadow winner matching the official one. Clare, Paul and I were there in person for the announcement at the Wellcome Collection in London. When we briefly spoke to the judges’ chair, Edmund de Waal, later in the evening, he said he was “relieved” that their decision matched ours – but I think it was definitely the other way around!

Simon Chaplin, Director of Culture & Society at the Wellcome Trust, said that each year more and more books are being considered for the prize. De Waal revealed that the judges read 169 books over nine months in what was for him his most frightening book club ever. “To bring the worlds of medicine and health into urgent conversation” requires a “lyrical and disciplined choreography,” he said, and “how we shape stories of science … is crucial.” He characterized the judges’ discussions as both “personal and passionate.” The Wellcome-shortlisted books make a space for public debate, he insisted.

Judges Gordon, Paul-Choudhury, Critchlow, Ratcliffe and de Waal. Photo by Clare Rowland.

The judges brought each of the five authors present onto the stage one at a time for recognition. De Waal praised Ayobami Adebayo’s “narrative of hope and fear and anxiety” and Meredith Wadman’s “beautifully researched and paced thriller.” Dr Hannah Critchlow of Magdalene College, Cambridge called Lindsey Fitzharris’s The Butchering Art “gruesome yet fascinating.” Oxford English professor Sophie Ratcliffe applauded Kathryn Mannix’s book and its mission. New Scientist editor-in-chief Sumit Paul-Choudhury said Mark O’Connell’s book is about the future “just as much as what it means to be human in the twenty-first century.” Journalist and mental health campaigner Bryony Gordon thanked Sigrid Rausing for her “great honesty and stunning prose.”

But there can only be one winner, and it was Mark O’Connell, who couldn’t be there as his wife is/was giving birth to their second child imminently. The general feeling in the room was that he’d made the right call by deciding to stay with his family. He must be feeling like the luckiest man on earth right now, to have a baby plus £30,000! Max Porter, O’Connell’s editor at Granta and the author of Grief Is the Thing with Feathers, received the award on his behalf and read out the extremely witty speech he’d written in advance.

Afterwards we spoke to three of the shortlisted authors. Kathryn Mannix said she’d so enjoyed following our shadow panel reviews and that it was for the best that O’Connell won, as any other outcome might have spoiled the lovely girls’ club the others had going on during the weekend’s events. I got two signatures and we nabbed a quick photo with Lindsey Fitzharris. It was also great to meet Simon Savidge, the king of U.K. book blogging, and author and vlogger Jen Campbell. Other ‘celebrities’ spotted: Sarah Bakewell and Ben Goldacre.

This time I stayed long enough for pudding canapés to come around – raspberry cake pops and mini meringues with strawberries. What a great idea! On the way out I again acquired a Wellcome goody bag: this year’s tote with a copy of The Butchering Art, which I only had on Kindle before. I’d also treated myself to this brainy necklace from the Wellcome shop and wore it to the ceremony. An all-round great evening. I’m looking forward to next year’s prize season already!

Paul, Lindsey Fitzharris, Clare and me.

Wellcome Book Prize Shadow Panel Decision

Addiction, death, infertility, surgery, transhumanism and vaccines: It’s been quite the varied reading list for the five of us this spring! Lots of science, lots of medicine, but also a lot of stories and imagination.

After some conferring and voting, we have arrived at our shadow panel winner for the Wellcome Book Prize 2018: To Be a Machine by Mark O’Connell.

Rarely have I been so surprised to love a book. It’s a delight to read, and no matter what your background or beliefs are, it will give you plenty to think about. It goes deep down, beneath our health and ultimately our mortality, to ask what the essence of being human is.

Here’s what the rest of the shadow panel has to say about our pick:

Annabel: “O’Connell, as a journalist and outsider in the surprisingly diverse field of transhumanism, treats everyone with respect: asking the questions, but not judging, to get to the heart of the transhumanists’ beliefs. For a subject based in technology, To Be a Machine is a profoundly human story.”

Clare: “The concept of transhumanism may not be widely known or understood yet, but O’Connell’s engaging and fascinating book explains the significance of the movement and its possible implications both in the distant future and how we live now.”

Laura: “My brain feels like it’s been wired slightly differently since reading To Be a Machine. It’s not just about weird science and weird scientists, but how we come to terms with the fact that even the luckiest of us live lives that are so brief.”

Paul: “An interesting book that hopefully will provoke further discussion as we embrace technology and it envelops us.”

On Monday we’ll find out which book the official judges have chosen. I could see three or four of these as potential winners, so it’s very hard to say who will take home the £30,000.

Who are you rooting for?

Wellcome Book Prize Shortlist: To Be a Machine by Mark O’Connell

The topic of this shortlisted book didn’t particularly appeal to me, so I was pleasantly surprised to enjoy it. Transhumanism is about using technology to help us overcome human limitations and radically extend our lifespan. Many of the strategies O’Connell, a Dublin-based freelance writer with a literature background, profiles are on the verge of science fiction. Are we looking at liberation from the rules of biology, or enslavement to technology? His travels take him to the heart of this very American, and very male, movement.

Cryogenic freezing: The first person was cryogenically frozen in 1966. Max More’s Alcor Life Extension Foundation in Scottsdale, Arizona offers whole-body or head-only (“neuro”) options for $200,000 or $80,000. More argues that the residents of Alcor are somewhere between living and dead. These entities are held in suspension in the belief that technology will one day allow us to upload the contents of the mind into a new vessel.

- This approach seems to conceive of the human mind/consciousness as pure information to be computed.

Cyborgs: Grindhouse Wetware, near Pittsburgh, aims to turn people into literal cyborgs. Tim Cannon had a Circadia device the size of a deck of cards implanted in his arm for three months to take biometric measurements. Other colleagues have implanted RFID chips. He intends to have his arms amputated and replaced by superior prostheses as soon as the technology is available.

Cyborgs: Grindhouse Wetware, near Pittsburgh, aims to turn people into literal cyborgs. Tim Cannon had a Circadia device the size of a deck of cards implanted in his arm for three months to take biometric measurements. Other colleagues have implanted RFID chips. He intends to have his arms amputated and replaced by superior prostheses as soon as the technology is available.

- That may seem extreme, but think how bound people already are to machines: O’Connell calls his smartphone a “mnemonic prosthesis” during his research travels.

Mortality as the enemy: Many transhumanists O’Connell meets speak of aging and death as an affront to human dignity. We mustn’t be complacent, they argue, but must oppose these processes with all we’re worth. One of the key people involved in that fight is Aubrey de Grey of SENS (“Strategies for Engineered Negligible Senescence”), and Google has also gotten in on it with their “Calico” project.

- O’Connell recounts explaining aging and death to his three-year-old son; his wife chipped in that – according to “Dada’s book” – perhaps by the time the boy is grown up death will no longer be a problem.

The Singularity: Posited by Ray Kurzweil, the Singularity is the future point at which artificial intelligence will surpass humanity. O’Connell likens it to the Christian idea of the Rapture, itself a moment of transcendence. At a conference on transhumanism and religion in Piedmont, California, he encounters Terasem, a religion founded recently by a transhumanist and transgender person.

- To my surprise, To Be a Machine makes frequent reference to religious ideas: O’Connell thinks of transhumanism as an attempt to reverse the Fall and become godlike, and he often describes the people he meets as zealots or saints, driven by the extremity of their beliefs. Both religion and transhumanism could be seen as a way of combating nihilism and insisting on the meaning of human life.

O’Connell’s outsider position helped me to engage with the science; he’s at least as interested, if not more so, in the deeper philosophical questions that transhumanism raises. I would caution that a grounding in religion and philosophy could be useful, as the points of reference used here range from the Gnostic gospels and St. Augustine to materialism and Nietzsche. But anyone who’s preoccupied with human nature should find the book intriguing.

You could also enjoy this purely as a zany travelogue along the lines of Elif Batuman’s The Possessed and Donovan Hohn’s Moby-Duck. The slapstick antics of the robots at the DARPA Robotics Challenge and the road trip in Zoltan Istvan’s presidential campaign Immortality Bus are particularly amusing. O’Connell’s Dickensian/Wildean delight in language is evident, and I also appreciated his passing references to William Butler Yeats.

It could be argued, however, that O’Connell was not the ideal author of this book. He is not naturally sympathetic to transhumanism; he’s pessimistic and skeptical, often wondering whether the proponents he meets are literally insane (e.g., to think that they are in imminent danger of being killed by robots). Most of the relevant research, even when conducted by Europeans, is going on in the USA, particularly in the Bay Area. So why would an Irish literary critic choose transhumanism as the subject for his debut? It’s a question I asked myself more than once, though it never stopped me from enjoying the book.

The title (from an Andy Warhol quote) may reference machines, but really this is about what it means to be human. O’Connell even ends with a few pages on his own cancer scare, a reminder that our bodies are flawed machines. I encourage you to give this a try even if you think you have no particular interest in technology or science fiction. It could also give a book club a lot to discuss.

Favorite lines:

“We exist, we humans, in the wreckage of an imagined splendor. It was not supposed to be this way: we weren’t supposed to be weak, to be ashamed, to suffer, to die. We have always had higher notions of ourselves. … The frailty is the thing, the vulnerability. This infirmity, this doubtful convalescence we refer to, for want of a better term, as the human condition.”

My rating:

See what the rest of the shadow panel has to say about this book:

Annabel’s review: “I loved this book from the front cover to the back, starting with its title. … He writes with empathy and a good deal of humour which makes the text always readable and entertaining, while provoking his readers to think deeply about their own beliefs.”

Clare’s review: “O’Connell’s prose style is wordy and ironic. He is pleasingly sceptical about many aspects of transhumanism. … It is an entertaining book which provides a lot of food for thought for a layperson like myself.”

Laura’s review: “Often, I found that his description of his own internal questions would mirror mine. This is a really fantastic book, and for me, a clear front runner for the Wellcome Book Prize.”

Paul’s review: “An interesting book that hopefully will provoke further discussion as we embrace technology and it envelops us.”

My gut feeling: Though they highlight opposite approaches to death – transcending it versus accepting it – this and Kathryn Mannix’s With the End in Mind seem to me the two shortlisted books of the most pressing importance. I’d be happy to see either of them win. To Be a Machine is an awful lot of fun to read, and it seems like a current favorite for our panel.

Shortlist strategy:

- I’m coming close to the end of my skim of The Vaccine Race by Meredith Wadman.

- I’m still awaiting a review copy of Mayhem by Sigrid Rausing, which I’ll be featuring as part of the official Wellcome Book Prize shortlist blog tour.

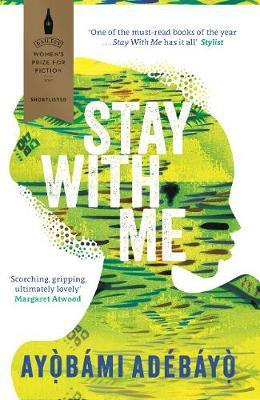

Wellcome Book Prize Shortlist: Stay with Me by Ayobami Adebayo

“Women manufacture children and if you can’t you are just a man. Nobody should call you a woman.”

On balance, I’m glad that the Wellcome Book Prize shortlist reading forced me to go back and give Stay with Me another try. Last year I read the first 15% of this debut novel for a potential BookBrowse review but got bored with the voice and the story, rather unfairly dismissing it as a rip-off of Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. I also doubted that the health theme was strong enough for it to make the Wellcome shortlist, but that’s because I hadn’t read far enough to realize just how many medical conditions come up for consideration: it’s not just infertility, but also false pregnancy, cot death (or SIDS), sickle cell disease, and impotence.

This time around I found Yejide a more sympathetic character. The words that open this review are cruel ones spoken by her mother-in-law. Her desperation to become and stay a mother drives her to extreme measures that also give a window onto indigenous religion in Nigeria: ‘breastfeeding’ a goat on the Mountain of Jaw-Dropping Miracles, and allowing an act of ritual scarification to prevent the return of an abiku, or spirit child (I’ve heard that one narrates Ben Okri’s Booker Prize-winning 1991 novel, The Famished Road).

This time around I found Yejide a more sympathetic character. The words that open this review are cruel ones spoken by her mother-in-law. Her desperation to become and stay a mother drives her to extreme measures that also give a window onto indigenous religion in Nigeria: ‘breastfeeding’ a goat on the Mountain of Jaw-Dropping Miracles, and allowing an act of ritual scarification to prevent the return of an abiku, or spirit child (I’ve heard that one narrates Ben Okri’s Booker Prize-winning 1991 novel, The Famished Road).

Polygamy is another Nigerian custom addressed in the novel. Yejide’s husband, Akinyele Ajayi, allows himself to be talked into taking another wife, Funmilayo, when Yejide hasn’t produced a child after four years. There’s irony in the fact that polygyny is considered a valid route to pregnancy while polyandry is not, and traditional versus Western values are contrasted in the different generations’ reactions to polygamy: does it equate to adultery?

There are some welcome flashes of humor in the novel, such as when Yejide deliberately serves a soup made with three-day-old beans and Funmi gets explosive diarrhea. I also enjoyed the ladies’ gossip at Yejide’s hair salon. However, the story line tends towards the soap operatic, and well before halfway it starts to feel like just one thing after another: A lot happens, but to no apparent purpose. I was unconvinced by the choices the author made in terms of narration (split between Yejide and Akin, both in first person but with some second person address to each other) and structure (divided between 2008 and the main action starting in the 1980s). We see certain scenes from both spouses’ perspective, but that doubling doesn’t add anything to the overall picture. The writing is by turns maudlin (“each minute pregnant with hope, each second tremulous with tragedy”) and uncolloquial (“afraid that my touch might … careen him into the unknown”).

Things that at first seemed insignificant to me – the 1993 election results, what happens to Funmi, the one major scene set in 2008 – do eventually take on more meaning, and there is a nice twist partway through as well as a lovely surprise at the end. I did feel the ache of the title phrase as it applies to this couple’s children and marriage, so threatened by “all the mess of love and life that only shows up as you go along.” It all makes for truly effortless reading that I gobbled up in chunks of 50 or 100 pages – which indicates authorial skill, of course – yet this seems to me a novel more interesting for the issues it addresses than for its story and writing.

My rating:

See also:

My gut feeling: I would be very surprised if a novel won two years in a row. While the medical situations examined here are fairly wrenching, Stay with Me isn’t strong enough to win. Its appearance on the shortlist (for the Women’s Prize, too) is honor enough, I think.

Shortlist strategy:

- I’m one-third through The Vaccine Race by Meredith Wadman but have started skimming because it’s dense and not quite as laymen-friendly as The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks and The Emperor of All Maladies, the two books its subject matter is most reminiscent of for me.

- On Friday I started To Be a Machine by Mark O’Connell, which I’m also one-third through and have taken away on our mini-holiday. This is the shortlisted book whose topic appealed to me the least, so I’m pleasantly surprised to be enjoying it so much. It helps that O’Connell comes at the science as an outsider – he’s a freelance writer with a literature background, and he’s interested in the deeper philosophical questions that transhumanism raises.

- I’m awaiting a review copy of Mayhem by Sigrid Rausing, which I’ll be featuring as part of the official Wellcome Book Prize shortlist blog tour.

Winterson does her darndest to write like Ali Smith here (no speech marks, short chapters and sections, random pop culture references). Cross Smith’s Seasons quartet with the vague aims of the Hogarth Shakespeare project and Margaret Atwood’s

Winterson does her darndest to write like Ali Smith here (no speech marks, short chapters and sections, random pop culture references). Cross Smith’s Seasons quartet with the vague aims of the Hogarth Shakespeare project and Margaret Atwood’s

Night Boat to Tangier by Kevin Barry – I read the first 76 pages. The other week two grizzled Welsh guys came to deliver my new fridge. Their barely comprehensible banter reminded me of that between Maurice and Charlie, two ageing Irish gangsters. The long first chapter is terrific. At first these fellas seem like harmless drunks, but gradually you come to realize just how dangerous they are. Maurice’s daughter Dilly is missing, and they’ll do whatever is necessary to find her. Threatening to decapitate someone’s dog is just the beginning – and you know they could do it. “I don’t know if you’re getting the sense of this yet, Ben. But you’re dealing with truly dreadful fucken men here,” Charlie warns at one point. I loved the voices; if this was just a short story it would have gotten a top rating, but I found I had no interest in the backstory of how these men got involved in heroin smuggling.

Night Boat to Tangier by Kevin Barry – I read the first 76 pages. The other week two grizzled Welsh guys came to deliver my new fridge. Their barely comprehensible banter reminded me of that between Maurice and Charlie, two ageing Irish gangsters. The long first chapter is terrific. At first these fellas seem like harmless drunks, but gradually you come to realize just how dangerous they are. Maurice’s daughter Dilly is missing, and they’ll do whatever is necessary to find her. Threatening to decapitate someone’s dog is just the beginning – and you know they could do it. “I don’t know if you’re getting the sense of this yet, Ben. But you’re dealing with truly dreadful fucken men here,” Charlie warns at one point. I loved the voices; if this was just a short story it would have gotten a top rating, but I found I had no interest in the backstory of how these men got involved in heroin smuggling. The Man Who Saw Everything by Deborah Levy – I read the first 35 pages. There’s a lot of repetition; random details seem deliberately placed as clues. I’m sure there’s a clever story in here somewhere, but apart from a few intriguing anachronisms (in 1988 a smartphone is just “A small, flat, rectangular object … lying in the road. … The object was speaking. There was definitely a voice inside it”) there is not much plot or character to latch onto. I suspect there will be many readers who, like me, can’t be bothered to follow Saul Adler from London’s Abbey Road, where he’s hit by a car in the first paragraph, to East Berlin.

The Man Who Saw Everything by Deborah Levy – I read the first 35 pages. There’s a lot of repetition; random details seem deliberately placed as clues. I’m sure there’s a clever story in here somewhere, but apart from a few intriguing anachronisms (in 1988 a smartphone is just “A small, flat, rectangular object … lying in the road. … The object was speaking. There was definitely a voice inside it”) there is not much plot or character to latch onto. I suspect there will be many readers who, like me, can’t be bothered to follow Saul Adler from London’s Abbey Road, where he’s hit by a car in the first paragraph, to East Berlin. There’s only one title from the Booker shortlist that I’m interested in reading: Girl, Woman, Other by Bernardine Evaristo. I’ll be reviewing it later this month as part of a blog tour celebrating the Aké Book Festival, but as a copy hasn’t yet arrived from either the publisher or the library I won’t have gotten far into it before the Prize announcement.

There’s only one title from the Booker shortlist that I’m interested in reading: Girl, Woman, Other by Bernardine Evaristo. I’ll be reviewing it later this month as part of a blog tour celebrating the Aké Book Festival, but as a copy hasn’t yet arrived from either the publisher or the library I won’t have gotten far into it before the Prize announcement.

*However, I was delighted to find a copy of her 1991 novel, Varying Degrees of Hopelessness (just 182 pages, with short chapters often no longer than a paragraph and pithy sentences) in a 3-for-£1 sale at our local charity warehouse. Isabel, a 31-year-old virgin whose ideas of love come straight from the romance novels of ‘Babs Cartwheel’, hopes to find Mr. Right while studying art history at the Catafalque Institute in London (a thinly veiled Courtauld, where Ellmann studied). She’s immediately taken with one of her professors, Lionel Syms, whom she dubs “The Splendid Young Man.” Isabel’s desperately unsexy description of him had me snorting into my tea:

*However, I was delighted to find a copy of her 1991 novel, Varying Degrees of Hopelessness (just 182 pages, with short chapters often no longer than a paragraph and pithy sentences) in a 3-for-£1 sale at our local charity warehouse. Isabel, a 31-year-old virgin whose ideas of love come straight from the romance novels of ‘Babs Cartwheel’, hopes to find Mr. Right while studying art history at the Catafalque Institute in London (a thinly veiled Courtauld, where Ellmann studied). She’s immediately taken with one of her professors, Lionel Syms, whom she dubs “The Splendid Young Man.” Isabel’s desperately unsexy description of him had me snorting into my tea: This strange and somewhat entrancing debut novel is set in Arnott’s native Tasmania. The women of the McAllister family are known to return to life – even after a cremation, as happened briefly with Charlotte and Levi’s mother. Levi is determined to stop this from happening again, and decides to have a coffin built to ensure his 23-year-old sister can’t ever come back from the flames once she’s dead. The letters that pass between him and the ill-tempered woodworker he hires to do the job were my favorite part of the book. In other strands, we see Charlotte traveling down to work at a wombat farm in Melaleuca, a female investigator lighting out after her, and Karl forming a close relationship with a seal. This reminded me somewhat of The Bus on Thursday by Shirley Barrett and Orkney by Amy Sackville. At times I had trouble following the POV and setting shifts involved in this work of magic realism, though Arnott’s writing is certainly striking.

This strange and somewhat entrancing debut novel is set in Arnott’s native Tasmania. The women of the McAllister family are known to return to life – even after a cremation, as happened briefly with Charlotte and Levi’s mother. Levi is determined to stop this from happening again, and decides to have a coffin built to ensure his 23-year-old sister can’t ever come back from the flames once she’s dead. The letters that pass between him and the ill-tempered woodworker he hires to do the job were my favorite part of the book. In other strands, we see Charlotte traveling down to work at a wombat farm in Melaleuca, a female investigator lighting out after her, and Karl forming a close relationship with a seal. This reminded me somewhat of The Bus on Thursday by Shirley Barrett and Orkney by Amy Sackville. At times I had trouble following the POV and setting shifts involved in this work of magic realism, though Arnott’s writing is certainly striking.  The Unauthorised Biography of Ezra Maas by Daniel James: A twisty, clever meta novel about “Daniel James” trying to write a biography of Ezra Maas, an enigmatic artist who grew up a child prodigy in Oxford and attracted a cult following in 1960s New York City, where he was a friend of Warhol et al. (See

The Unauthorised Biography of Ezra Maas by Daniel James: A twisty, clever meta novel about “Daniel James” trying to write a biography of Ezra Maas, an enigmatic artist who grew up a child prodigy in Oxford and attracted a cult following in 1960s New York City, where he was a friend of Warhol et al. (See

Please Read This Leaflet Carefully by Karen Havelin: A debut novel by a Norwegian author that proceeds backwards to examine the life of a woman struggling with endometriosis and raising a young daughter. I’m very keen to read this one.

Please Read This Leaflet Carefully by Karen Havelin: A debut novel by a Norwegian author that proceeds backwards to examine the life of a woman struggling with endometriosis and raising a young daughter. I’m very keen to read this one.