I Do Love a Good Book List

In the same way that I love following literary prize races (see my post on that topic from a couple weeks ago), I adore a good book list. This includes everything from an inspirational lifetime reading menu such as 1001 Books You Must Read Before You Die to those gimmicky “5 Novels About…” or “10 Books for People Who Like…” lists you get on websites like BuzzFeed and the Huffington Post.

Every time a new ‘Best Books Ever’ type of checklist comes out, I gleefully scan through to figure out how many I’ve already read. Usually the disappointing results smack me back and remind me that for all my voracious reading, I still haven’t read many of the classics everyone’s supposed to have read by my age.

Here for your delectation (if you like this sort of thing) is a sampling of the book lists I’ve bookmarked over the years, with my running total noted in brackets after each:

THE BEST OF THE BEST

The 100 Greatest Novels of All Time, as chosen by the Guardian in 2003 [33]

1000 novels everyone must read, as chosen by the Guardian in 2009 (interestingly, they divide it up by genre: Love Stories, Crime Fiction, Comedy, Family & Self, State of the Nation, Science Fiction & Fantasy, and War & Travel) [155 + 2 in progress]

The 100 greatest non-fiction books, as chosen by the Guardian in 2011 [7]

Vintage 21, a set of 21 modern classics chosen in 2011 [14]

100 novels everyone should read, as chosen by the Telegraph in April [29]

The 100 best novels written in English, as chosen by Robert McCrum in the Guardian last week [34]

PARTICULAR TIMES OF LIFE

65 Books You Need To Read in Your 20s, from BuzzFeed (alas, it’s too late for many of us) [13, 12 of which I think I read in my 20s]

25 Books to Help You Survive Your Mid-20s, from Bustle (ditto) [9, all read in my 20s, I think]

Conversely, here’s 15 Books You Should Definitely Not Read in Your 20s from Flavorwire (well, that’s alright, then) [I disobeyed them on 4 counts]

21 Books Every Woman Should Read By 35, from Bustle (I’ve got 3.13 years to work on it) [5; I left The Flamethrowers unfinished]

11 Novels That Expectant Parents Should Read Instead of Parenting Books, from Electric Literature (my mother may be reading this, so I must hastily add that THIS SITUATION DOES NOT APPLY TO ME!) [6]

SPECIFIC AUTHORS

The Best Hemingway Novels, on Publishers Weekly [2 out of 6, but A Moveable Feast is my favorite from him]

The 13 Best John Steinbeck Books, on Publishers Weekly [3]

The 10 Best Mark Twain Books, on Publishers Weekly [just 1!]

23 Contemporary Writers You Should Have Read by Now, on Reader’s Digest [I’ve read 3, Elizabeth Spencer, Percival Everett and Pamela Erens]

Beyond Murakami: 7 Japanese Authors to Read, on Book Riot [none so far]

SPECIFIC GENRES

20 Classic Novels You’ve Never Heard of, from QwikLit [I’ve heard of plenty of these, but only read 1]

12 Fiction Books That Will Shape Your Theology, from RELEVANT Magazine [3]

The 10 Best Books Shorter Than 150 Pages, on Publishers Weekly [2]

10 Best Southern Gothic Books, on Publishers Weekly [none so far]

10 Novels with Multiple Narratives, on Publishers Weekly [2]

The 10 Best Short Story Collections You’ve Never Read, on Publishers Weekly [they got that right; none so far]

The top 10 novels about childbirth, on the Guardian (again, NOT APPLICABLE TO ME!) [7]

I also highly recommend Nancy Pearl’s Book Lust series of four books, each one divided into themes.

ONE LAST LIST

Not a book list, but it may be useful for all you bibliophiles:

The 25 Best Websites for Literature Lovers, by Flavorwire

Do you love book lists as much as I do? Are you addicted to counting how many you’ve read from a checklist?

How do you fare on the lists above?

Graphic Novels for Newbies

Following on from last week’s article on quick reads…

I sometimes wonder if counting graphic novels on my year lists is a bit like cheating, since some are little more than comic books. However, the majority of graphic novels I read have a definite storyline and more words on a page than your average comic. When I worked in London I took advantage of the extensive public library holdings there and tried out a lot of graphic novelists’ work that was new to me. Some of my favorites are Alison Bechdel, Posy Simmonds, Audrey Niffenegger and Joe Sacco. As it happens, I’ve never officially reviewed graphic novels (nor do I own any), but here’s a handful I’ve enjoyed, along with my reading notes:

Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic by Alison Bechdel

Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic by Alison Bechdel

This memoir in graphic novel form is super. Bechdel puts the ‘fun’ in both dysfunctional family and funeral home – the family business her father inherited in small-town Pennsylvania. All through her 1970s upbringing, as Alison grew up coveting men’s shirts and feeling strange quivers of suspicion when she encountered the word “lesbian” in the dictionary, her father was leading a double life, sleeping with the younger men who babysat his kids or helped out with his twin passions of gardening and home renovation.

In an ironic sequence of events, the coming-out letter Alison sent home from college was followed just weeks later by her mother’s revelation of her father’s homosexual indiscretions and their upcoming divorce, and then no more than a few months later by her father’s sudden death. Bruce Bechdel was run down by a Sunbeam Bread truck as he was crossing the road with an armload of cleared brush from a property he was renovating. Was it suicide, or just a horribly arbitrary accident? (The Sunbeam Bread detail sure makes one cringe.) In any case, it was a “mort imbécile,” just as Camus characterized any death by automobile.

Bechdel traces the hints of queerness in her family, the moments when she and her father saw into each other and recognized something familiar. She also muses on the family as a group of frustrated and isolated artists each striving, unfulfilled, towards perfection. This is a thoughtful, powerful memoir, and no less so for being told through a comic strip.

(Bechdel’s Are You My Mother? was also on my BookTrib list of mother–daughter memoirs to read for Mother’s Day.)

This sweet, autobiographical coming-of-age story in graphic novel form is not quite as likable and quick-witted as Fun Home, but it has similar themes such as sexual awakening and the difficulty of understanding one’s parents. Blankets are a linking metaphor: the quilt Craig’s first love, Raina, makes for him; huddling in the same bed with his little brother Phil for warmth during freezing Wisconsin winters; and playing ‘storm at sea’ with the covers.

There’s also an interesting loss-of-faith element to the narrative. Craig is brought up in your average Midwestern fundamentalist Evangelical church and attends youth group, camp, etc. (where he meets Raina); the pastor even wants him to consider going into the ministry, but he doesn’t fit in here – even in the Christian subculture he’s forced into a fringe group of outsiders. Writing and drawing are acts of self-creation and self-preservation. He wants to find a way to use his drawing for good but no one seems to see a value in it. Thus everything, or nothing in particular, leads him to reject his faith when he gets to college.

How satisfying it is to leave a mark on a blank surface. To make a map of my movement – no matter how temporary.

The drawings are lush and bold (though even more so in Thompson’s Habibi). [SPOILERS ahead!] I appreciated how Thompson denies the satisfaction of a happy ending to Craig and Raina’s love story; it’s more realistic this way, recognizing that high school sweethearts rarely stay together. As Raina says, “everything ENDS…everything DEGENERATES, CRUMBLES – so why bother getting started in the first place?” And yet the beauty and power in memory of young love remains, thus Thompson’s rhapsodizing here.

Mrs Weber’s Omnibus by Posy Simmonds

Mrs Weber’s Omnibus by Posy Simmonds

[a collection of her comics for the Guardian]

As with the Garfield cartoons, you get to see the development of Simmonds’s style and the characters, as well as the march of fashion over the period 1977–1993. Very clever skewering of middle class liberal values and political correctness gone mad: the characters (especially polytechnic sociology lecturer George, in the Department of Liberal Studies, and children’s book author Wendy Weber) espouse these values, but their actions don’t always live up to the tolerance they preach. Here are some of the themes:

- 1980s politics: reactionary against Thatcherism; youth unemployment and purposelessness; income inequality; economic and social injustice

- Hypocrisy, avoiding unpleasant truths, compromising youthful ideals

- Middle vs. upper-middle / upper class: second homes, private education

- Place of women: the irony that stay-at-home motherhood is idealized and the difficulties of working motherhood denied (women – liberated to do what?)

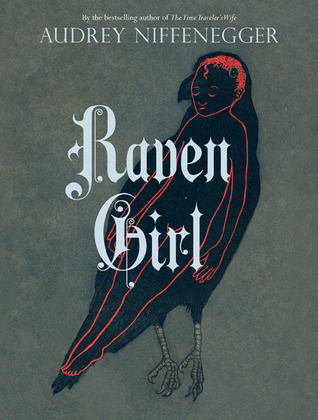

Raven Girl by Audrey Niffenegger

Raven Girl by Audrey Niffenegger

A lovely and simple fairy tale, with classical plot elements like transformation and true love transcending all boundaries. In a quaint English setting, a country postman is tasked with delivering a letter to an address he’s never seen before:

Dripping Rock

Raven’s Nest

2 Flat Drab Manor

East Underwhelm, Otherworld

EE1 LH9 [postcode = East of East, Lower Heights]

Here the postman meets a young raven fallen out of her nest, takes her home to mend her and they fall in love. Even when her wing heals and she can fly, she chooses to stay with him. Their daughter is a mixed creature; she can only croak, but she has no wings and so is raised as a human child. At university she meets a plastic surgeon who can create human-animal chimeras; she begs him to make her wings – a mixture of science and magic. It involves bloody surgery and painful recovery, but in the end she has the wings she’s always felt were hers. Her identity is described in terms very much like Jan Morris’s in Conundrum, when describing her sex change and her knowledge that she was really a girl: “My mother is a raven and my father is a postman, but I feel that truly I should have been a raven.”

Like Niffenegger’s other work, there’s an ever so slightly uncomfortable blend of sinister/grotesque elements with charming, innocuous magic.

Jimmy Corrigan, the Smartest Kid on Earth by Chris Ware

Jimmy Corrigan, the Smartest Kid on Earth by Chris Ware

This is probably the most peculiar graphic novel I’ve ever read. It’s the story of Jimmy Corrigan, a sad-sack workaholic who, at 36, has no friends apart from his mother, who constantly telephones him. One day he gets a letter from the father he’s never met, asking him to come meet him. And so Jimmy gets on a plane from Chicago out to suburban Michigan. Corrigan is one of those unfortunate-looking fellows who has a potato for a head and a wispy comb-over, and could be anywhere between 30 and 60; he looked little different as a child in the flashback scenes – somewhat like Charlie Brown, also in his depression, diffidence and inability to speak to women.

I much preferred the historical interludes looking at his grandfather (another Jimmy) and his years growing up in Chicago with the World’s Fair under construction. I also liked the more random additions such as patterns for cutting and folding your own model village or business cards with ‘scenic views’ of today’s Waukosha, MI on them.

Parental (verbal) abuse and neglect is a recurring theme, as are bullying from peers, car accidents, and Superman. There’s also an uncomfortable amount of imagined violence – either homicide or suicide.

Also recommended:

Palestine by Joe Sacco

Couch Fiction by Philippa Perry

Days of the Bagnold Summer by Joff Winterhart

Do you read graphic novels? What are some of your favorites?

I Like Big Books and I Cannot Lie

You can never get a cup of tea large enough or a book long enough to suit me.

~ C. S. Lewis

Here’s to doorstoppers! Books of 500 pages or more [the page count is in brackets for each of the major books listed below] can keep you occupied for entire weeks of a summer – or for just a few days if they’re gripping enough. There’s something delicious about getting wrapped up in an epic story and having no idea where the plot will take you. Doorstoppers are the perfect vacation companions, for instance. I have particularly fond memories of getting lost in Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell by Susanna Clarke [782] on a week’s boating holiday in Norfolk with my in-laws, and of devouring The Crimson Petal and the White by Michel Faber [835] on a long, queasy ferry ride to France.

Here’s to doorstoppers! Books of 500 pages or more [the page count is in brackets for each of the major books listed below] can keep you occupied for entire weeks of a summer – or for just a few days if they’re gripping enough. There’s something delicious about getting wrapped up in an epic story and having no idea where the plot will take you. Doorstoppers are the perfect vacation companions, for instance. I have particularly fond memories of getting lost in Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell by Susanna Clarke [782] on a week’s boating holiday in Norfolk with my in-laws, and of devouring The Crimson Petal and the White by Michel Faber [835] on a long, queasy ferry ride to France.

I have an MA in Victorian Literature, so I was used to picking up novels that ranged between 600 and 900 pages. Of course, one could argue that the Victorians were wordier than necessary due to weekly deadlines, the space requirements of serialized stories, and the popularity of subsequent “triple-decker” three-volume publication. Still, I think Charles Dickens’s works, certainly, stand the test of time. His David Copperfield [~900] is still my favorite book. I adore his sprawling stories crammed full of major and minor characters. Especially in a book like David Copperfield that spans decades of a character’s life, the sheer length allows you time to get to know the protagonist intimately and feel all his or her struggles and triumphs as if they were your own.

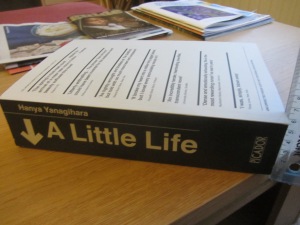

I felt the same about A Little Life by Hanya Yanagihara [720], which I recently reviewed for Shiny New Books. Jude St. Francis is a somewhat Dickensian character anyway, for his orphan origins at least, and even though the novel is told in the third person, it is as close a character study as you will find in contemporary literature. I distinctly remember two moments in my reading, one around page 300 and one at 500, when I looked up and thought, “where in the world will this go?!” Even as I approached the end, I couldn’t imagine how Yanagihara would leave things. That, I think, is one mark of a truly masterful storyteller.

Speaking of Dickensian novels, in recent years I’ve read two Victorian pastiches that have an authentically Victorian page count, too: The Luminaries by Eleanor Catton [848] and Death and Mr. Pickwick by Stephen Jarvis [816]. The Luminaries, which won the 2013 Booker Prize, has an intricate structure (based on astrological charts) that involves looping back through the same events – making it at least 200 pages too long.

It was somewhat disappointing to read Jarvis’s debut novel in electronic format; without the physical signs of progress – a bookmark advancing through a huge text block – it’s more difficult to feel a sense of achievement. Once again one might argue that the book’s digressive nature makes it longer than necessary. But with such an accomplished debut that addresses pretty much everything ever written or thought about The Pickwick Papers, who could quibble?

John Irving’s novels are Dickensian in their scope as well as their delight in characters’ eccentricities, but fully modern in terms of themes – and sexual explicitness. Along with Dickens, he’s a mutual favorite author for my husband and me, and his A Prayer for Owen Meany [637] numbers among our collective favorite novels. Most representative of his style are The World According to Garp and The Cider House Rules.

Here are a handful of other long novels I’ve read and reviewed within the last few years (the rating is below each description):

All the Light We Cannot See by Anthony Doerr [531] – The 2015 Pulitzer Prize winner; set in France and Germany during World War II.

All the Light We Cannot See by Anthony Doerr [531] – The 2015 Pulitzer Prize winner; set in France and Germany during World War II.

In the Light of What We Know by Zia Haider Rahman [555] – Digressive intellectualizing about race, class and war as they pertain to British immigrants.

The Son by Philipp Meyer [561] – An old-fashioned Western with hints of Cormac McCarthy.

The Son by Philipp Meyer [561] – An old-fashioned Western with hints of Cormac McCarthy.

The Art of Fielding by Chad Harbach [512] – Baseball is a window onto modern life in this debut novel about homosocial relationships at a small liberal arts college.

“A Discovery of Witches” fantasy trilogy by Deborah Harkness: A Discovery of Witches [579], Shadow of Night [584], and The Book of Life [561] – Thinking girl’s vampire novels, with medieval history and Oxford libraries thrown in.

“A Discovery of Witches” fantasy trilogy by Deborah Harkness: A Discovery of Witches [579], Shadow of Night [584], and The Book of Life [561] – Thinking girl’s vampire novels, with medieval history and Oxford libraries thrown in.

And here’s the next set of doorstoppers on the docket:

Of Human Bondage by W. Somerset Maugham [766] – A Dickensian bildungsroman about a boy with a clubfoot who pursues art, medicine and love.

The Goldfinch by Donna Tartt [864] – I have little idea of what this is actually about. A boy named Theo, art, loss, drugs and 9/11? Or just call it life in general. I’ve read Tartt’s other two books and was enough of a fan to snatch up a secondhand paperback for £1.

A Brief History of Seven Killings by Marlon James [686] (as with A Little Life, the adjective in the title surely must be tongue-in-cheek!) – The starting point is an assassination attempt on Bob Marley in the late 1970s, but this is a decades-sweeping look at Jamaican history. I won a copy in a Goodreads giveaway.

A Suitable Boy by Vikram Seth [1,474!] – A sprawling Indian family saga. Apparently he’s at work on a sequel entitled A Suitable Girl.

This Thing of Darkness by Harry Thompson [744] – A novel about Charles Darwin and his relationship with Robert FitzRoy, captain of the Beagle.

The Last Chronicle of Barset by Anthony Trollope [891] – As the title suggests, this is the final novel in Trollope’s six-book “Chronicles of Barsetshire” series. Alas, reading this one requires reading the five previous books, so this is more like a 5,000-page commitment…

Now, a confession: sometimes I avoid long books because they just seem like too much work. It’s sad but true that a Dickens novel takes me infinitely longer to read than a modern novel of similar length. The prose is simply more demanding, there’s no question about it. So if I’m faced with a choice between one 800-page novel that I know could take me months of off-and-on reading and three or four 200–300-page contemporary novels, I’ll opt for the latter every time. Part of this also has to do with meeting my reading goals for the year: when you’re aiming for 250 titles, it makes more sense to read a bunch of short books than a few long ones. I need to get better about balancing quality and quantity.

How do you feel about long books? Do you seek them out or shy away? Comments welcome!

Recommended Easter Reading

Unlike Christmas, Easter is a holiday that might not lend itself so easily to reading lists. December is the perfect time to be reading cozy books with wintry scenes of snow and hearth, or old-time favorites like Charles Dickens. Christmas-themed books and short stories are a whole industry, it seems. Lent and Advent both prize special foods, traditions and symbols, but beyond devotional reading there doesn’t seem to be an Easter book scene. Nonetheless, I have a handful of books I’d like to recommend for the run-up to Easter, whether for this year or the future.

I hadn’t heard of Michael Arditti until I reviewed his novel The Breath of Night – a taut, Heart of Darkness-inspired thriller about a young man searching for a missing priest in the Philippines – for Third Way magazine in late 2013. He deserves to be better known. Easter (2000), his third novel, earned him comparisons to Iris Murdoch and Barbara Pym. His nuanced picture of modern Christianity, especially the Anglican Church, is spot-on.

I’ve just finished Part One, which traces the week between Palm Sunday and Easter Sunday in a fictional London parish, St Mary-in-the-Vale, Hampstead. Structured around the services of Holy Week and punctuated with bits of liturgy, the novel moves between the close third-person perspectives of various clergy and parishioners. Huxley Grieve, the vicar, is – rather inconveniently – experiencing serious doubts in this week of all weeks. And this at a time when the new Bishop of London, Ted Bishop (“Bishop by name, bishop by calling,” he quips), has announced his mission to root out the poison of liberalism from the Church.

So far I’m reminded of a cross between Susan Howatch and David Lodge (especially in How Far Can You Go?), with a dash of the BBC comedy Rev thrown in. Reverend Grieve’s sermons may be achingly earnest, but the novel is also very funny indeed. Here’s a passage, almost like a set of stage directions, from the Palm Sunday service: “The procession moves up the nave. The Curate leads the donkey around the church. It takes fright at the cloud of incense and defecates by the font.”

Lazarus Is Dead, Richard Beard

Lazarus Is Dead, Richard Beard

In this peculiar novel-cum-biography, Beard attempts to piece together everything that has ever been said, written and thought about the biblical character of Lazarus. The best sections have Beard ferreting out the many diseases from which Lazarus may have been suffering, and imagining what his stench – both in life and in death – must have been like. (“He stinketh,” as the Book of John pithily puts it.)

Alongside these reasonable conjectures is a strange, invented backstory for Jesus and Lazarus: when they were children Jesus failed to save Lazarus’ younger brother from drowning and Lazarus has borne a lifelong grudge. A Roman official is able to temporarily convince Lazarus that he needs to take up the mantle of the Messiah because he came back to life: he has the miracle to prove the position, whether he wants it or not. The end of the novel follows the strand of the Passion Week, though in a disconnected and halfhearted fashion.

Beard’s interest is not that of a religious devotee or a scriptural scholar, but of a skeptical postmodern reader. Lazarus is a vehicle for questions of textual accuracy, imagination, and the creation of a narrative of life and death. His unprecedented second life must make him irresistible to experimental novelists. Beard’s follow-up novel, Acts of the Assassins, is also Bible-themed; it’s a thriller that imagines the Roman Empire still in charge today.

Dead Man Walking, Sister Helen Prejean

Dead Man Walking, Sister Helen Prejean

No matter your current thoughts on the death penalty, you owe it to yourself to read this book with an open mind. I read it in the run-up to Easter 2007, and would recommend it as perfect reading for the season. As I truly engaged with themes of guilt and retribution, I felt the reality of death row was brought home to me for the first time. Many of the men Prejean deals with in this book we would tend to dismiss as monsters, yet Jesus is the God who comes for the lost and the discounted, the God who faces execution himself.

The film version, which conflates some of the characters and events of the book, is equally affecting. I saw it first, but it does not ruin the reading experience in any way.

The Last Week: What the Gospels Really Teach about Jesus’s Final Days in Jerusalem, Marcus J. Borg and John Dominic Crossan

The Last Week: What the Gospels Really Teach about Jesus’s Final Days in Jerusalem, Marcus J. Borg and John Dominic Crossan

Marcus Borg, who just died on January 21st, has been one of the most important theologians in my continuing journey with Christianity. His Reading the Bible Again for the First Time and The Heart of Christianity are essential reading for anyone who’s about to give up on the faith. In this day-by-day account, mostly referencing the Gospel of Mark, Borg and Crossan convey all that is known about the historical Jesus’ last week and death. They collaborated on a second book, The First Christmas, which does the same for Jesus’ birth.

And now for two more unusual, secular selections…

Bellman & Black, Diane Setterfield

Bellman & Black, Diane Setterfield

Call me morbid, but I love English graveyards. My most enduring Easter memory is of dawn services at the country church in my husband’s hometown. In the weak half-light, with churchyard rooks croaking a near-deafening chorus, the overwhelming sense was of rampant wildness. The congregation huddled around a bonfire while a black-cloaked vicar intoned the story of scripture, from creation to the coming of Christ, as loudly as possible over the rooks – trying to win mastery over the night, and score a point for civilization in the meantime.

This anecdote goes some way toward explaining why I rather enjoyed Bellman and Black – but why many others won’t. Setterfield’s second novel is a peculiar beast, a bit like a classic suspense story but also an English country fable. Protagonist William Bellman is part Job and part Faustus. At age ten, he makes a catapult that kills a rook. Thereafter, his life is plagued by death, despite his successful career as an entrepreneur at a cloth mill. Can he make a deal with the Devil – or, rather, the sinister Mr. Black – that will stop the cycle of deaths?

Bellman’s daughter Dora is a wonderful character, and because I love birds anyway and have strong, visceral memories involving rooks in particular, I enjoyed Setterfield’s symbolic use of them. However, many will be bored to tears by details of cloth-making and dyeing in early nineteenth-century England. Setterfield evokes her time period cannily, but in such a painstaking manner that the setting does not feel entirely natural. Here’s hoping for a return to form with Setterfield’s third novel.

This was the first book I ever borrowed from the Adult Fiction section of the public library, when I was eight years old. It quickly became a favorite, and though I didn’t reread it over and over like I did the Chronicles of Narnia, it still has a strong place in my childhood memories. Why have I chosen it for this list? Well, it’s about rabbits: a warren comes under threat from English countryside development and human interference.

I loved a little story Rachel Joyce inserts in her novel The Love Song of Miss Queenie Hennessy. Taking over from another nun, a young, air-headed nurse at Queenie’s hospice resumes reading Watership Down to a patient. At the end the patient cries, “Oh, it’s so sad, those poor rabbits” and the nurse replies, “What rabbits?” (You’d think the cover might have given it away!) It’s a good laugh, but also reflects how carefully Adams characterizes – one might say anthropomorphizes – each rabbit; you might forget they’re actually animals.

Do you have any favorite books to read or reread at particular holidays?

Happy spring reading!