Recent Poetry Reads

I love interspersing poetry with my other reading, and this year it seems like I’m getting to more of it than ever. Although I try to have a poetry collection on the go at all times, I still consider myself a novice and enjoy discovering new-to-me poets. However, I know many readers who totally avoid poetry because they assume they won’t understand it or it would feel too much like hard work.

Sinking into poems is certainly a very different experience from opening up a novel or a nonfiction narrative. Often I read parts of a poem two or three times – to make sure I’ve taken it in properly, or just to savor the language. I try to hear the lines aloud in my head so I can appreciate the sonic techniques at work, whether rhyming or alliteration. Reading or listening to poetry engages a different part of the brain, and it may be best to experience it in something of a dreamlike state.

I hope you’ll find a book or two that appeals from the selection below.

Thousandfold by Nina Bogin (2019)

This is a lovely collection whose poems devote equal time to interactions with nature and encounters with friends and family. Birds – along with their eggs and feathers – are a frequent presence. Often a particular object will serve as a totem as the poet remembers the most important people in her life: her father’s sheepskin coat, her grandmother’s pink bathrobe, and the slippers her late husband shuffled around in – a sign of how diminished he’d become due to dementia. Elsewhere Bogin greets a new granddaughter and gives thanks for the comforting presence of her cat. Gentle rhymes and half-rhymes lend a playful or incantatory nature. I’d recommend this to fans of Linda Pastan.

This is a lovely collection whose poems devote equal time to interactions with nature and encounters with friends and family. Birds – along with their eggs and feathers – are a frequent presence. Often a particular object will serve as a totem as the poet remembers the most important people in her life: her father’s sheepskin coat, her grandmother’s pink bathrobe, and the slippers her late husband shuffled around in – a sign of how diminished he’d become due to dementia. Elsewhere Bogin greets a new granddaughter and gives thanks for the comforting presence of her cat. Gentle rhymes and half-rhymes lend a playful or incantatory nature. I’d recommend this to fans of Linda Pastan.

My rating:

Thousandfold will be published by Carcanet Press on January 31st. My thanks to the publisher for the free copy for review.

Sweet Shop by Amit Chaudhuri (2019)

I was previously unfamiliar with Chaudhuri’s work, and unfortunately this insubstantial book about his beloved Indian places and foods hasn’t lured me into trying any more. The one poem I liked best was “Creek Row,” about a Calcutta lane used as a shortcut: “you are a thin, short-lived, / decaying corridor” and an “oesophageal aperture”. I also liked, as stand-alone lines go, “Refugees are periodic / like daffodils.” Nothing else stood out for me in terms of language, sound or theme. Poetry is so subjective; all I can say is that some poets will click with you and others don’t. In any case, the atmosphere is similar to what I found in Korma, Kheer and Kismet: Five Seasons in Old Delhi by Pamela Timms.

I was previously unfamiliar with Chaudhuri’s work, and unfortunately this insubstantial book about his beloved Indian places and foods hasn’t lured me into trying any more. The one poem I liked best was “Creek Row,” about a Calcutta lane used as a shortcut: “you are a thin, short-lived, / decaying corridor” and an “oesophageal aperture”. I also liked, as stand-alone lines go, “Refugees are periodic / like daffodils.” Nothing else stood out for me in terms of language, sound or theme. Poetry is so subjective; all I can say is that some poets will click with you and others don’t. In any case, the atmosphere is similar to what I found in Korma, Kheer and Kismet: Five Seasons in Old Delhi by Pamela Timms.

My rating:

My thanks to Salt Publishing for the free copy for review.

Windfall by Miriam Darlington (2008)

Before I picked this up from the bookstall at the New Networks for Nature conference in November, I had no idea that Darlington had written poetry before she turned to nature writing (Otter Country and Owl Sense). These poems are rooted in the everyday: flipping pancakes, sitting down to coffee, tending a garden, smiling at a dog. Multiple poems link food and erotic pleasure; others make nature the source of exaltation. I loved her descriptions of a heron (“a standing stone / perched in silt / a wrap of grey plumage”) and a blackbird (“the first bird / a glockenspiel in C / an improvisation on morning / a blue string of notes”), Lots of allusions and delicious alliteration. Pick this up if you’re missing Mary Oliver.

Before I picked this up from the bookstall at the New Networks for Nature conference in November, I had no idea that Darlington had written poetry before she turned to nature writing (Otter Country and Owl Sense). These poems are rooted in the everyday: flipping pancakes, sitting down to coffee, tending a garden, smiling at a dog. Multiple poems link food and erotic pleasure; others make nature the source of exaltation. I loved her descriptions of a heron (“a standing stone / perched in silt / a wrap of grey plumage”) and a blackbird (“the first bird / a glockenspiel in C / an improvisation on morning / a blue string of notes”), Lots of allusions and delicious alliteration. Pick this up if you’re missing Mary Oliver.

My rating:

A Responsibility to Awe by Rebecca Elson (2018)

Elson, an astronomer who worked on the Hubble Space Telescope, died of breast cancer; this is a reprint of her posthumous 2001 publication. Along with a set of completed poems, the volume includes an autobiographical essay and extracts from her notebooks. Her impending mortality has a subtle presence in the book. I focused on the finished poems, which take their metaphors from physics (“Dark Matter”), mathematics (“Inventing Zero”) and evolution (indeed, “Evolution” was my favorite). In the essay that closes the book, Elson remembers long summers of fieldwork and road trips across Canada with her geologist father (I was reminded of Margaret Atwood’s Cat’s Eye), and traces her academic career as she bounced between the United States and Great Britain.

Elson, an astronomer who worked on the Hubble Space Telescope, died of breast cancer; this is a reprint of her posthumous 2001 publication. Along with a set of completed poems, the volume includes an autobiographical essay and extracts from her notebooks. Her impending mortality has a subtle presence in the book. I focused on the finished poems, which take their metaphors from physics (“Dark Matter”), mathematics (“Inventing Zero”) and evolution (indeed, “Evolution” was my favorite). In the essay that closes the book, Elson remembers long summers of fieldwork and road trips across Canada with her geologist father (I was reminded of Margaret Atwood’s Cat’s Eye), and traces her academic career as she bounced between the United States and Great Britain.

My rating:

My thanks to Carcanet Press for the free copy for review.

These next two were on the Costa Prize for Poetry shortlist, along with Hannah Sullivan’s Three Poems, which was one of my top poetry collections of 2018 and recently won the T. S. Eliot Prize. I first encountered the work of all three poets at last year’s Faber Spring Party.

Us by Zaffar Kunial (2018)

Many of these poems are about split loyalties and a composite identity – Kunial’s father was Kashmiri and his mother English – and what the languages we use say about us. He also writes about unexpectedly developing a love for literature, and devotes one poem to Jane Austen and another to Shakespeare. My favorites were “Self Portrait as Bottom,” about doing a DNA test (“O I am translated. / The speech of numbers. / Here’s me in them / and them in me. … What could be more prosaic? / I am split. 50% Europe. / 50% Asia.”), and the title poem, a plea for understanding and common ground.

Many of these poems are about split loyalties and a composite identity – Kunial’s father was Kashmiri and his mother English – and what the languages we use say about us. He also writes about unexpectedly developing a love for literature, and devotes one poem to Jane Austen and another to Shakespeare. My favorites were “Self Portrait as Bottom,” about doing a DNA test (“O I am translated. / The speech of numbers. / Here’s me in them / and them in me. … What could be more prosaic? / I am split. 50% Europe. / 50% Asia.”), and the title poem, a plea for understanding and common ground.

My rating:

Soho by Richard Scott (2018)

When I saw him live, Scott read two of the amazingly intimate poems from this upcoming collection. One, “cover-boys,” is about top-shelf gay porn and what became of the models; the other, “museum,” is, on the face of it, about mutilated sculptures of male bodies in the Athens archaeological museum, but also, more generally, about “the vulnerability of / queer bodies.” If you appreciate the erotic verse of Mark Doty and Andrew McMillan, you need to pick this one up immediately. Scott channels Verlaine in a central section of gritty love poems and Whitman in the final, multi-part “Oh My Soho!”

When I saw him live, Scott read two of the amazingly intimate poems from this upcoming collection. One, “cover-boys,” is about top-shelf gay porn and what became of the models; the other, “museum,” is, on the face of it, about mutilated sculptures of male bodies in the Athens archaeological museum, but also, more generally, about “the vulnerability of / queer bodies.” If you appreciate the erotic verse of Mark Doty and Andrew McMillan, you need to pick this one up immediately. Scott channels Verlaine in a central section of gritty love poems and Whitman in the final, multi-part “Oh My Soho!”

My rating:

Don’t Call Us Dead by Danez Smith (2017)

Like Claudia Rankine’s Citizen, this is a book whose aims I can admire even though I didn’t particularly enjoy reading it. It’s about being black and queer in an America where both those identifiers are dangerous, where guns and HIV are omnipresent threats. “reader, what does it / feel like to be safe? white?” Smith asks. “when i was born, i was born a bull’s-eye.” The narrator and many of the other characters are bruised and bloody, with blood used literally but also metaphorically for kinship and sexual encounters. By turns tender and biting, exultant and uncomfortable, these poems are undeniably striking, and a necessary wake-up call for readers who may never have considered the author’s perspective.

Like Claudia Rankine’s Citizen, this is a book whose aims I can admire even though I didn’t particularly enjoy reading it. It’s about being black and queer in an America where both those identifiers are dangerous, where guns and HIV are omnipresent threats. “reader, what does it / feel like to be safe? white?” Smith asks. “when i was born, i was born a bull’s-eye.” The narrator and many of the other characters are bruised and bloody, with blood used literally but also metaphorically for kinship and sexual encounters. By turns tender and biting, exultant and uncomfortable, these poems are undeniably striking, and a necessary wake-up call for readers who may never have considered the author’s perspective.

My rating:

Up next: This Pulitzer-winning collection from the late Mary Oliver, whose work I’ve had mixed success with before (Dream Work is by far her best that I’ve read so far). We lost two great authors within a week! RIP Diana Athill, too, who was 101.

Any recent poetry reads you can recommend to me?

Novellas in November, Part 1: 3 Fiction, 3 Nonfiction

This is my third year of prioritizing novellas for my November reading. I have plenty more on the go that I’ll try to write up as the month progresses. For this first installment I review three each of my recent fiction and nonfiction reads, all of them 150 pages or fewer.

Fiction:

Lady into Fox by David Garnett (1922)

[53 pages]

I accidentally did things the wrong way round: a few months back I read Sarah Hall’s Madame Zero, which includes the BBC National Short Story Prize 2013 winner “Mrs Fox,” clearly modeled on Garnett’s half-charming, half-horrible fable. In both, an upper-middle-class marriage is derailed when the wife turns into a fox. Here Mr. Tebrick sends away the servants and retreats from the world to look after Silvia, who grows increasingly feral. To start with the vixen will wear clothing, sleep in a bed, play cards and eat table scraps, but soon she’s hunting birds outdoors. Before long she’s effectively a wild creature, though she still shows affection to Tebrick when he comes to visit her den.

I accidentally did things the wrong way round: a few months back I read Sarah Hall’s Madame Zero, which includes the BBC National Short Story Prize 2013 winner “Mrs Fox,” clearly modeled on Garnett’s half-charming, half-horrible fable. In both, an upper-middle-class marriage is derailed when the wife turns into a fox. Here Mr. Tebrick sends away the servants and retreats from the world to look after Silvia, who grows increasingly feral. To start with the vixen will wear clothing, sleep in a bed, play cards and eat table scraps, but soon she’s hunting birds outdoors. Before long she’s effectively a wild creature, though she still shows affection to Tebrick when he comes to visit her den.

Anyone in a partnership will experience a bittersweet sense of recognition at how Tebrick and Silvia try to accommodate each other’s differences and make compromises to maintain a relationship in defiance of the world’s disapproval and danger. Beware unsentimental animal peril throughout. I downloaded it from Project Gutenberg.

The Old Man and the Sea by Ernest Hemingway (1952)

[99 pages]

It’s a wonder I never read this Pulitzer winner in high school. Like that other syllabus favorite, Steinbeck’s The Pearl, it’s a Great American novella praised for spare prose and weighty symbolism. My two decades’ worth of preconceptions were proven accurate insomuch as this is a gloomy story about the nobility but ultimate futility of human striving. After 84 days without a catch, Santiago returns to the waters off of Havana and finally gets a bite. Even after the harrowing process of reeling in the 18-foot marlin, his struggle isn’t over.

It’s a wonder I never read this Pulitzer winner in high school. Like that other syllabus favorite, Steinbeck’s The Pearl, it’s a Great American novella praised for spare prose and weighty symbolism. My two decades’ worth of preconceptions were proven accurate insomuch as this is a gloomy story about the nobility but ultimate futility of human striving. After 84 days without a catch, Santiago returns to the waters off of Havana and finally gets a bite. Even after the harrowing process of reeling in the 18-foot marlin, his struggle isn’t over.

This is my third experience with Hemingway’s fiction; I remain unconvinced. I appreciated some of the old man’s solitary ruminations on purpose and determination – “My big fish must be somewhere,” “Now is no time to think of what you do not have. Think of what you can do with what there is” – though they sound rather like sound bites. And I kept almost falling asleep while reading this (until the sharks showed up), which almost never happens. Take that as you will.

Ghost Wall by Sarah Moss (2018)

[149 pages]

It’s the late 1980s and teenager Silvie Hampton and her parents have joined a university-run residential archaeology course in the North of England, near bogs where human sacrifice once took place. Her father is a Rochdale-area bus driver, but British prehistory is his all-consuming hobby. They’ll skin rabbits with stone tools and forage for roots and berries. What could be better?! As it turns out, it’s a stifling summer, and the students can’t sneak off to civilization often enough. Mocked for her family’s accent, Silvie is uncomfortably aware of her class. And, always, she must tread carefully to avoid angering her father, who punishes perceived offenses with his belt or his fists.

It’s the late 1980s and teenager Silvie Hampton and her parents have joined a university-run residential archaeology course in the North of England, near bogs where human sacrifice once took place. Her father is a Rochdale-area bus driver, but British prehistory is his all-consuming hobby. They’ll skin rabbits with stone tools and forage for roots and berries. What could be better?! As it turns out, it’s a stifling summer, and the students can’t sneak off to civilization often enough. Mocked for her family’s accent, Silvie is uncomfortably aware of her class. And, always, she must tread carefully to avoid angering her father, who punishes perceived offenses with his belt or his fists.

Women’s bodies and what can be done to them is central; as the climax approaches, the tricksy matter of consent arises. Though I enjoyed Silvie’s sarcastic voice, I was underwhelmed for much of the book, yet ended up impressed by how much is conveyed in so few pages. If you haven’t read anything by Sarah Moss, do so immediately.

Nonfiction:

Losing Susan: Brain Disease, the Priest’s Wife, and the God Who Gives and Takes Away by Victor Lee Austin (2016)

[146 pages]

Austin, an Episcopal priest and academic, met his wife Susan at St. John’s College in Santa Fe, New Mexico. She was his companion for nearly 40 years. Unusually for a cancer story, it wasn’t the beginning of the end when Susan was diagnosed with an astrocytoma brain tumor in 1993; surgery was successful and she lived for another 19 years, but white-matter disease, a side effect of radiation, meant that her brain function was continually diminishing.

Austin, an Episcopal priest and academic, met his wife Susan at St. John’s College in Santa Fe, New Mexico. She was his companion for nearly 40 years. Unusually for a cancer story, it wasn’t the beginning of the end when Susan was diagnosed with an astrocytoma brain tumor in 1993; surgery was successful and she lived for another 19 years, but white-matter disease, a side effect of radiation, meant that her brain function was continually diminishing.

The book gives a clear sense of Susan’s personality despite the progression of her illness, and of the challenges of being a caregiver while holding down a career. I enjoyed the details of the human story of coping with suffering, but in overlaying a spiritual significance on it Austin lost me somewhat. “God, who had given us so much, now gave us this evil,” he writes. While once this kind of language would have meant something to me, now it alienates me. I valued this more as a straightforward bereavement memoir than as a theological treatise.

The Secret Life of the Owl by John Lewis-Stempel (2017)

[84 pages]

“There is something about owls. More than any other family of birds they produce a reaction in us, and have done so across time and continents.” Some species-specific natural/cultural histories can be long-winded, giving significantly more information than your averagely interested lay reader needs (Foxes Unearthed, for instance), but Lewis-Stempel’s short book about Britain’s owls gets it just right.

“There is something about owls. More than any other family of birds they produce a reaction in us, and have done so across time and continents.” Some species-specific natural/cultural histories can be long-winded, giving significantly more information than your averagely interested lay reader needs (Foxes Unearthed, for instance), but Lewis-Stempel’s short book about Britain’s owls gets it just right.

He gives some general information about the family, surveys the native species and occasional visitors, gives tips for telling them apart – I’m going to photograph a page on the difference between the five major species’ pellets for future reference – and shares legends and poems that feature owls (including a jaunty little Tennyson piece that reads like a folk song; I’ll suggest that my husband turn it into one). The black-and-white illustrations by Beci Kelly are charming, too. It’s a shame I missed this when it first came out, but it would still make a great gift for a bird lover this Christmas.

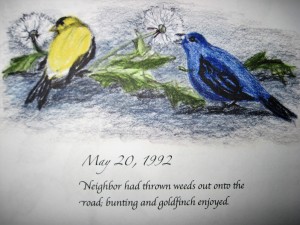

Pages from a Nature-Lover’s Diary by Kathleen A. Renninger (2013)

[72 pages]

These are lovely excerpts from nature sketchbooks Renninger kept between 1987 and 2013. My mother bought the self-published book from the author at a craft fair, and I enjoyed spotting lots of familiar place names from southern central Pennsylvania, where my mother and sister used to live. In the past I’ve unfairly considered the area devoid of natural beauty, but it’s clear from Renninger’s encounters that the wildlife is out there if you’re patient and lucky enough to find it – mostly birds and insects, but even larger mammals like foxes and bears.

These are lovely excerpts from nature sketchbooks Renninger kept between 1987 and 2013. My mother bought the self-published book from the author at a craft fair, and I enjoyed spotting lots of familiar place names from southern central Pennsylvania, where my mother and sister used to live. In the past I’ve unfairly considered the area devoid of natural beauty, but it’s clear from Renninger’s encounters that the wildlife is out there if you’re patient and lucky enough to find it – mostly birds and insects, but even larger mammals like foxes and bears.

Many of her sightings are by chance: near her feeders or clothesline, or while driving past fields or down a residential street. Each month ends with a poem; these are slightly florid, but so earnest that they won me over. There are plentiful punctuation issues and the cursive font is a challenge to read, but the captured moments and the sense of the seasons’ passing make for a sweet book I’d recommend to anyone with a local interest.

Many of her sightings are by chance: near her feeders or clothesline, or while driving past fields or down a residential street. Each month ends with a poem; these are slightly florid, but so earnest that they won me over. There are plentiful punctuation issues and the cursive font is a challenge to read, but the captured moments and the sense of the seasons’ passing make for a sweet book I’d recommend to anyone with a local interest.

Have you read any of these novellas? Which one takes your fancy?

The Feather Thief by Kirk Wallace Johnson

The Feather Thief is a delightful read that successfully combines many genres – biography, true crime, ornithology, history, travel and memoir – to tell the story of an audacious heist of rare bird skins from the Natural History Museum at Tring in 2009. Somehow I managed not to hear about it at the time, but it was huge news in terms of museum collections and endangered species crime. The tendrils of this thorny case wind around Victorian explorers, tycoons, and fashionistas through to modern obsessions with music, fly-fishing and refugees.

The Feather Thief is a delightful read that successfully combines many genres – biography, true crime, ornithology, history, travel and memoir – to tell the story of an audacious heist of rare bird skins from the Natural History Museum at Tring in 2009. Somehow I managed not to hear about it at the time, but it was huge news in terms of museum collections and endangered species crime. The tendrils of this thorny case wind around Victorian explorers, tycoons, and fashionistas through to modern obsessions with music, fly-fishing and refugees.

Author Kirk Wallace Johnson worked for USAID in Iraq, heading up the reconstruction of Fallujah, then founded a non-profit organization rehoming refugees in America. Plagued by PTSD, he turned to fly-fishing as therapy, and this was how he heard about the curious case of Edwin Rist, who stole the bird specimens from Tring to sell the bright feathers to fellow hobbyists who tie elaborate Victorian-style fishing flies.

Rist, from upstate New York, was a 20-year-old flautist studying at the Royal Academy of Music in London. Since age 11 he’d been fixated on fly-tying, especially old-fashioned salmon ties, which use exotic feathers or ordinary ones dyed to look like them. An online friend told him he should check out Tring – the museum Walter Rothschild’s financier father built for him as a twenty-first birthday present – when he got to London. In 2008 Rist scoped out the collection, pretending to be photographing the birds of paradise for a friend’s book.

A year later he took the train to Tring one summer night with an empty suitcase and a glass cutter, broke in through a window, stole 300 bird skins, and made it back to his flat without incident. The museum only discovered the crime a month later, by accident. Rist sold many feathers and whole birds via a fly-tying forum and on eBay. It was nearly another year and a half before the police knocked on his door, having been alerted by a former law enforcement officer who encountered a museum-grade bird skin at the Dutch Fly Fair and asked where it came from.

An interior shot showing some plates of fishing flies.

Here is where things get really interesting, at least for me. Rist confessed immediately, but a psychological evaluation diagnosed him with Asperger’s; on the strength of that mental health defense he was given a suspension and a large fine, but no jail time, so he graduated from the Royal Academy as normal and auditioned for jobs. The precedent was a case from 2000 in which a young man with Asperger’s who stole human remains from a Bristol graveyard was exonerated.

The book is in three parts: the first gives historical context about specimen collection and the early feather trade; the second is a blow-by-blow of Rist’s crime and the aftermath, including the trial; and the third goes into Wallace’s own investigation process. He started by attending a fly-tying symposium, where he felt like an outsider and even received vague threats: Rist was now a no-go subject for this community. But Wallace wasn’t going to be deterred. Sixty-four bird skins were still missing, and his quest was to track them down. He started by contacting Rist’s confirmed customers, then interviewed Rist himself in Germany and traveled to Norway to meet someone who might have been Rist’s accomplice – or fall guy.

From the back cover.

I happened to be a bit too familiar with the related history – I’ve read a lot of books that touch on Alfred Russel Wallace, whose specimens formed the core of the Tring collection, as well as a whole book on the feather trade for women’s hats and the movement against the extermination, which led to the formation of the Audubon Society (Kris Radish’s The Year of Necessary Lies). This meant that I was a little impatient with the first few chapters, but if you are new to these subjects you shouldn’t have that problem. For me the highlights were the reconstruction of the crime itself and Wallace’s inquiry into whether the Asperger’s diagnosis was accurate and a fair excuse for Rist’s behavior.

This whole story is stranger than fiction, which would make it a great selection for readers who don’t often pick up nonfiction, perhaps expecting it to be dry or taxing. Far from it. This is the very best sort of nonfiction: wide-ranging, intelligent and gripping.

My rating:

The Feather Thief was published in the UK by Hutchinson on April 26th. My thanks to Najma Finlay for the free copy for review.

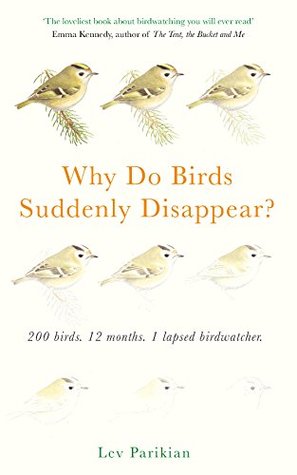

Blog Tour Review: Why Do Birds Suddenly Disappear? by Lev Parikian

Lev Parikian was a keen birdwatcher when he was 11, but as an adult he barely remembered most of what he used to know about birds. He’d confidently declare that he’d seen a nightingale and then be too embarrassed to later admit it was actually a skylark. Also, he had to acknowledge that he hadn’t been completely honest as a preteen birder: No way had he seen a black redstart, for instance. Probably about 30% of his childhood sightings could be dismissed as cheats or downright lies. As the birdwatching bug bit again at the start of 2016, he decided it was time to set the record straight. His aim? To see 200 birds in a year, with no twitching (driving many miles to see a reported rarity) and no cheating.

Lev Parikian was a keen birdwatcher when he was 11, but as an adult he barely remembered most of what he used to know about birds. He’d confidently declare that he’d seen a nightingale and then be too embarrassed to later admit it was actually a skylark. Also, he had to acknowledge that he hadn’t been completely honest as a preteen birder: No way had he seen a black redstart, for instance. Probably about 30% of his childhood sightings could be dismissed as cheats or downright lies. As the birdwatching bug bit again at the start of 2016, he decided it was time to set the record straight. His aim? To see 200 birds in a year, with no twitching (driving many miles to see a reported rarity) and no cheating.

Most of the book is a chronological tour through 2016, with each month’s new sightings totaled up at the end of the chapter. Being based in London isn’t the handicap one might expect – there’s a huge population of parakeets there nowadays, and the London Wetland Centre in Barnes is great for water birds – but Parikian also fills in his list through various trips around the country. He picks up red kites while in Windsor for a family wedding, and his list balloons in April thanks to trips to Minsmere and Rainham Marshes, where he finds additions like bittern and marsh harrier. The Isle of Wight, Scotland, Lindsifarne, North Norfolk… The months pass and the numbers mount until it’s the middle of December and his total is hovering at 196. Will he make it? I wouldn’t dare spoil the result for you!

I’ve always enjoyed ‘year-challenge’ books, everything from Julie Powell’s Julie and Julia to Nina Sankovitch’s Tolstoy and the Purple Chair, so I liked this memoir’s air of self-imposed competition, and its sense of humor. Having accompanied my husband on plenty of birdwatching trips, I could relate to the alternating feelings of elation and frustration. I also enjoyed the mentions of Parikian’s family history and career as a freelance conductor – I’d like to read more about this in his first book, Waving, Not Drowning (2013). This is one for fans of Alexandra Heminsley’s Leap In and Kyo Maclear’s Birds Art Life, or for anyone who needs reassurance that it’s never too late to pick up a new skill or return to a beloved hobby.

Lastly, I must mention what a beautiful physical object this book is. The good folk of Unbound have done it again. The cover image and endpapers reproduce Alan Harris’s lovely sketch of a gradually disappearing goldcrest, and if you lift the dustjacket you’re rewarded with the sight of some cheeky bird footprints traipsing across the cover.

Some favorite passages:

“Birders love a list. Day lists, week lists, month lists, year lists, life lists, garden lists, county lists, walk-to-work lists, seen-from-the-train lists, glimpsed-out-of-the-bathroom-window-while-doing-a-poo lists.”

“It’s one thing sitting in your favourite armchair, musing on the plumage differences between first- and second-winter black-headed gulls, but that doesn’t help identify the scrubby little blighter that’s just jigged into that bush, never to be seen again. And it’s no use asking them politely to damn well sit still blast you while I jot down the distinguishing features of your plumage in this notebook dammit which pocket is it in now where did I put the pencil ah here it is oh bugger it’s gone. They just won’t. Most disobliging.”

“There is a word in Swedish, gökotta, for the act of getting up early to listen to birdsong, but the knowledge that this word exists, while heartwarming, doesn’t make it any easier. It’s a bitter pill, this early rising, but my enthusiasm propels me to acts of previously unimagined heroism, and I set the alarm for an optimistic 5 a.m., before reality prompts me to change it to 5.15, no 5.30, OK then 5.45.”

My rating:

Why Do Birds Suddenly Disappear? was published by Unbound on May 17th. My thanks to the publisher for the free copy for review.

I was delighted to be invited to participate in the blog tour for Why Do Birds Suddenly Disappear? See below for details of where other reviews and features have appeared or will be appearing soon (including on my hubby’s blog on Thursday!).

Blood Ties by Ben Crane: Artist Ben Crane has developed a passion for birds of prey, raising hawks and training as a falconer. “I saw that my feelings towards nature, and birds of prey in particular, ran in parallel with my feelings for my son,” he writes. Blood Ties accordingly cuts between the story of rehabilitating a pair of rescued sparrowhawks named Girl and Boy and a parallel story about raising his son as a part-time single father. Together these strands emphasize the common concerns that arise when caring for any creature. Crane’s descriptive language is memorably sharp. Whatever struggles his Asperger’s entails, it seems to heighten his observational skills. Pruning the travel segments would have produced a more focused memoir, but this is a powerful story all the same – of the ties that bind us, both to nature and our own families. (Full review in February 8th issue.)

Blood Ties by Ben Crane: Artist Ben Crane has developed a passion for birds of prey, raising hawks and training as a falconer. “I saw that my feelings towards nature, and birds of prey in particular, ran in parallel with my feelings for my son,” he writes. Blood Ties accordingly cuts between the story of rehabilitating a pair of rescued sparrowhawks named Girl and Boy and a parallel story about raising his son as a part-time single father. Together these strands emphasize the common concerns that arise when caring for any creature. Crane’s descriptive language is memorably sharp. Whatever struggles his Asperger’s entails, it seems to heighten his observational skills. Pruning the travel segments would have produced a more focused memoir, but this is a powerful story all the same – of the ties that bind us, both to nature and our own families. (Full review in February 8th issue.)  Notes for the Everlost: A Field Guide to Grief by Kate Inglis: Inglis, a Nova Scotian photographer and children’s author, has written this delicate, playful handbook – something between a bereavement memoir and a self-help guide – for people who feel they might disappear into grief for ever. In 2007, Inglis’s identical twin sons were born premature, at twenty-seven weeks. Ben lived but Liam died. Every milestone in Ben’s life would serve as a reminder of the brother who should have been growing up alongside him. The unfairness was particularly keen on the day she returned to hospital for two appointments: Ben’s check-up and a report on Liam’s autopsy. Unable to sustain the eye-popping freshness of the prose in the introduction, Inglis resorts to some clichés in what follows. But this kooky, candid book will be valuable to anyone facing bereavement or supporting a loved one through it. (Full review in March 15th issue.)

Notes for the Everlost: A Field Guide to Grief by Kate Inglis: Inglis, a Nova Scotian photographer and children’s author, has written this delicate, playful handbook – something between a bereavement memoir and a self-help guide – for people who feel they might disappear into grief for ever. In 2007, Inglis’s identical twin sons were born premature, at twenty-seven weeks. Ben lived but Liam died. Every milestone in Ben’s life would serve as a reminder of the brother who should have been growing up alongside him. The unfairness was particularly keen on the day she returned to hospital for two appointments: Ben’s check-up and a report on Liam’s autopsy. Unable to sustain the eye-popping freshness of the prose in the introduction, Inglis resorts to some clichés in what follows. But this kooky, candid book will be valuable to anyone facing bereavement or supporting a loved one through it. (Full review in March 15th issue.)