The Blind Assassin Reread for #MARM, and Other Doorstoppers

It’s the fourth annual Margaret Atwood Reading Month (#MARM), hosted by Canadian blogger extraordinaire Marcie of Buried in Print. In previous years, I’ve read Surfacing and The Edible Woman, The Robber Bride and Moral Disorder, and Wilderness Tips. This year Laila at Big Reading Life and I did a buddy reread of The Blind Assassin, which was historically my favourite Atwood novel. I’d picked up a free paperback the last time I was at The Book Thing of Baltimore. Below are some quick thoughts based on what I shared with Laila as I was reading.

The Blind Assassin (2000)

Winner of the Booker Prize and Hammett Prize; shortlisted for the Orange Prize

I must have first read this about 13 years ago. The only thing I remembered before I started my reread was that there is a science fiction book-within-the-book. I couldn’t recall anything else about the setup before I read in the blurb about the suspicious circumstances of Laura’s death in 1945. Indeed, the opening line, which deserves to be famous, is “Ten days after the war ended, my sister Laura drove a car off a bridge.”

I always love novels about sisters, and Iris is a terrific narrator. Now a cantankerous elderly woman, she takes us back through her family history: her father’s button factory and his clashes with organizing workers, her mother’s early death, and her enduring relationship with their housekeeper, Reenie. Iris and Laura met a young man named Alex Thomas, a war orphan with radical views, at the factory’s Labour Day picnic, and it was clear early on that Laura was smitten, while Iris went on to marry Richard Griffen, a nouveau riche industrialist.

Interspersed with Iris’s recollections are newspaper articles that give a sense that the Chase family might be cursed, and excerpts from The Blind Assassin, Laura’s posthumously published novel. Daring for its time in terms of both explicit content and literary form (e.g., no speech marks), it has a storyline rather similar to 1984, with an upper-crust woman having trysts with a working-class man in his squalid lodgings. During their time snatched together, he also tells her a story inspired by the pulp sci-fi of the time. I was less engaged by the story-within-the-story(-within-the-story) this time around compared to Iris’s current life and flashbacks.

In the back of my mind, I had a vague notion that there was a twist coming, and in my impatience to see if I was right I ended up skimming much of the second half of the novel. My hunch was proven correct, but I was disappointed with myself that I wasn’t able to enjoy the journey more a second time around. Overall, this didn’t wow me on a reread, but then again, I am less dazzled by literary “tricks” these days. At the sentence level, however, the writing was fantastic, including descriptions of places, seasons and characters’ psychology. It’s intriguing to think about whether we can ever truly know Laura given Iris’s guardianship of her literary legacy.

If you haven’t read this before, find a time when you can give it your full attention and sink right in. It’s so wise on family secrets and the workings of memory and celebrity, and the weaving in of storylines in preparation for the big reveal is masterful.

Some favourite passages:

“What fabrications they are, mothers. Scarecrows, wax dolls for us to stick pins into, crude diagrams. We deny them an existence of their own, we make them up to suit ourselves – our own hungers, our own wishes, our own deficiencies.”

“Beginnings are sudden, but also insidious. They creep up on you sideways, they keep to the shadows, they lurk unrecognized. Then, later, they spring.”

“The only way you can write the truth is to assume that what you set down will never be read. Not by any other person, and not even by yourself at some later date. Otherwise you begin excusing yourself. You must see the writing as emerging like a long scroll of ink from the index finger of your right hand; you must see your left hand erasing it. Impossible, of course.”

My original rating (c. 2008):

My rating now:

What to read for #MARM next year, I wonder??

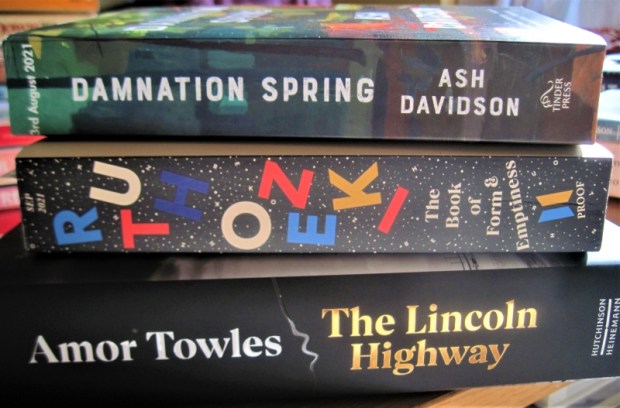

In general, I have been struggling mightily with doorstoppers this year. I just don’t seem to have the necessary concentration, so Novellas in November has been a boon. I’ve been battling with Ruth Ozeki’s latest novel for months, and another attempted buddy read of 460 pages has also gone by the wayside. I’ll write a bit more on this for #LoveYourLibrary on Monday, including a couple of recent DNFs. The Blind Assassin was only my third successful doorstopper of the year so far. After The Absolute Book, the other one was:

The Lincoln Highway by Amor Towles

In Towles’ third novel – a big, old-fashioned dose of Americana – brothers and pals set out from Nebraska on road and rail adventures to find a fortune in 1950s New York. The book features some fantastic characters. Precocious Billy steals every scene he appears in. Duchess is a delightfully flamboyant bounder, peppering his speech with malapropisms and Shakespeare quotes. However, Emmett is a dull protagonist, and it’s disappointing that Sally, one of just two main female characters, plays such a minor role. A danger with an episodic narrative is that random events and encounters pile up but don’t do much to further the plot. At nearly 200 pages in, I realized little of consequence had happened yet. A long road, then, with some ups and downs along the way, but Towles’ fans will certainly want to sign up for the ride.

In Towles’ third novel – a big, old-fashioned dose of Americana – brothers and pals set out from Nebraska on road and rail adventures to find a fortune in 1950s New York. The book features some fantastic characters. Precocious Billy steals every scene he appears in. Duchess is a delightfully flamboyant bounder, peppering his speech with malapropisms and Shakespeare quotes. However, Emmett is a dull protagonist, and it’s disappointing that Sally, one of just two main female characters, plays such a minor role. A danger with an episodic narrative is that random events and encounters pile up but don’t do much to further the plot. At nearly 200 pages in, I realized little of consequence had happened yet. A long road, then, with some ups and downs along the way, but Towles’ fans will certainly want to sign up for the ride.

See my full review for BookBrowse; see also my related article on Studebaker cars.

With thanks to Hutchinson for the free copy for review.

Anything by Atwood, or any doorstoppers, on your pile recently?

Ethan Frome by Edith Wharton (#NovNov Classics Week Buddy Read)

For the short classics week of Novellas in November, our buddy read is Ethan Frome by Edith Wharton (1911). You can download the book for free from Project Gutenberg here if you’d still like to join in.

Did you have to read Ethan Frome in school? For American readers, it’s likely that it was an assigned text in high school English. I didn’t happen to read it during my school days, but caught up in 2006 or 2008, I think, and was impressed with this condensed tragedy and the ambiance of a harsh New England winter. It struck me even more on a reread as a flawless parable of a man imprisoned by circumstance and punished for wanting more.

I had forgotten that the novella is presented as a part-imagined reconstruction of the sad events of Ethan Frome’s earlier life. A quarter-century later, the unnamed narrator is in Wharton’s fictional Starkfield, Massachusetts on business, and hears the bare bones of Ethan’s story from various villagers before meeting the man himself. Ethan, who owns a struggling sawmill, picks up extra money from odd jobs. He agrees to chauffeur the narrator to engineering projects in his sleigh, and can’t conceal his jealousy at a technical career full of travel – a reminder of what could have been had he been able to continue his own scientific studies. A blizzard forces the narrator to stay overnight in Ethan’s home, and the step over the threshold sends readers back in time to when Ethan was a young man of 28.

*There are SPOILERS in the following.*

Ethan’s household contains two very different women: his invalid wife, Zeena, eight years his elder; and her cousin, Mattie Silver, who serves as her companion and housekeeper. Mattie is dreamy and scatter-brained – not the practical sort you’d want in a carer role, but she had nowhere else to go after her parents’ death. She has become the light of Ethan’s life. By contrast, Zeena is shrewish, selfish, lazy and gluttonous. Wharton portrays her as either pretending or exaggerating about her chronic illness. Zeena has noticed that Ethan has taken extra pains with his appearance in the year since Mattie came to live with them, and conspires to get rid of Mattie by getting a new doctor to ‘prescribe’ her a full-time servant.

The plot turns on an amusing prop, “Aunt Philura Maple’s pickle-dish.” While Zeena is away for her consultation with Dr. Buck, Ethan and Mattie get one evening alone together. Mattie lays the table nicely with Zeena’s best dishes from the china cabinet, but at the end of their meal the naughty cat gets onto the table and knocks the red glass pickle dish to the floor, where it smashes. Before Ethan can obtain glue to repair it in secret, Zeena notices and acts as if this never-used dish was her most prized possession. She and Ethan are both to have what they most love taken away from them – but at least Ethan’s is a human being.

I had remembered that Ethan fell in love with a cousin (though I thought it was his cousin) and that there is a dramatic sledding accident. What I did not remember, however, was that the crash is deliberate: knowing they can never act on their love for each other, Mattie begs Ethan to steer them straight into the elm tree mentioned twice earlier. He dutifully does so. I thought I recalled that Mattie dies, while he has to live out his grief ever more. I was gearing myself up to rail against the lingering Victorian mores of the time that required the would-be sexually transgressing female to face the greatest penalty. Instead, in the last handful of pages, Wharton delivers a surprise. When the narrator enters the Frome household, he meets two women. One is chair-bound and sour; the other, tall and capable, bustles about getting dinner ready. The big reveal, and horrible irony, is that the disabled woman is Mattie, made bitter by suffering, while Zeena rose to the challenges of caregiving.

Ethan is a Job-like figure who lost everything that mattered most to him, including his hopes for the future. Unlike the biblical character, though, he finds no later reward. “Sickness and trouble: that’s what Ethan’s had his plate full up with, ever since the very first helping,” as one of the villagers tells the narrator. “He looks as if he was dead and in hell now!” the narrator observes. This man of sorrow is somehow still admirable: he and Zeena did the right thing in taking Mattie in again, and even when at his most desperate Ethan refused to swindle his customers to fund an escape with Mattie. In the end, Mattie’s situation is almost the hardest to bear: she only ever represented sweetness and love, and has the toughest lot. In some world literature, e.g. the Russian masters, suicide might be rendered noble, but here its attempt warrants punishment.

{END OF SPOILERS.}

I can see why some readers, especially if encountering this in a classroom setting, would be turned off by the bleak picture of how the universe works. But I love me a good classical tragedy, and admired this one for its neat construction, its clever use of foreshadowing and dread, its exploration of ironies, and its use of a rustic New England setting – so much more accessible than Wharton’s usual New York City high society. The cozy wintry atmosphere of Little Women cedes to something darker and more oppressive; “Guess he’s been in Starkfield too many winters,” a neighbor observes of Ethan. I could see a straight line from Jude the Obscure through Ethan Frome to The Great Gatsby: three stories of an ordinary, poor man who pays the price for grasping for more. I reread this in two sittings yesterday morning and it felt to me like a perfect example of how literature can encapsulate the human condition.

(Secondhand purchase) [181 pages]

My original rating (c. 2008):

My rating now:

Keep in touch via Twitter (@bookishbeck / @cathy746books) and Instagram (@bookishbeck / @cathy_746books), using the hashtag #NovNov. We’ll add any of your review links in to our master posts.

The Story of My Life by Helen Keller (#NovNov Nonfiction Buddy Read)

For nonfiction week of Novellas in November, our buddy read is The Story of My Life by Helen Keller (1903). You can download the book for free from Project Gutenberg here if you’d still like to join in.

Keller’s story is culturally familiar to us, perhaps from the William Gibson play The Miracle Worker, but I’d never read her own words. She was born in Alabama in 1880; her father had been a captain in the Confederate Army. An illness (presumed to be scarlet fever) left her blind and deaf at the age of 19 months, and she describes herself in those early years as mischievous and hot-tempered, always frustrated at her inability to express herself. The arrival of her teacher, Anne Sullivan, when Helen was six years old transformed her “silent, aimless, dayless life.”

I was fascinated by the glimpses into child development and education. Especially after she learned Braille, Keller loved books, but she believed she learned just as much from nature: “everything that could hum or buzz, or sing, or bloom, had a part in my education.” She loved to sit in the family orchard and would hold insects or fossils and track plant and tadpole growth. Her first trip to the ocean (Chapter 10) was a revelation, and rowing and sailing became two of her chief hobbies, along with cycling and going to the theatre and museums.

At age 10 Keller relearned to speak – a more efficient way to communicate than her usual finger-spelling. She spent winters in Boston and eventually attended the Cambridge School for Young Ladies in preparation for starting college at Radcliffe. Her achievements are all the more remarkable when you consider that smell and touch – senses we tend to overlook – were her primary ones. While she used a typewriter to produce schoolwork, a teacher spelling into her hand was still her main way to intake knowledge. Specialist textbooks for mathematics and multiple languages were generally not available in Braille. Digesting a lesson and completing homework thus took her much longer than it did her classmates, but still she felt “impelled … to try my strength by the standards of those who see and hear.”

It was surprising to find, at the center of the book, a detailed account of a case of unwitting plagiarism (Chapter 14). Eleven-year-old Keller wrote a story called “The Frost King” for a beloved teacher at the Perkins Institution for the Blind. He was so pleased that he printed it in one of their publications, but it soon came to his attention that the plot was very similar to “The Frost Fairies” in Birdie and His Friends by Margaret T. Canby. The tale must have been read to Keller long ago but become so deeply buried in the compost of a mind’s memories that she couldn’t recall its source. Some accused Keller and Sullivan of conspiring, and this mistrust more than the incident itself cast a shadow over her life for years to come. I was impressed by Keller discussing in depth something that it would surely have been more comfortable to bury. (I’ve sometimes had the passing thought that if I wrote a memoir I would structure it around my regrets or most embarrassing moments. Would that be penance or masochism?)

This short memoir was first serialized in the Ladies’ Home Journal. Keller was only 23 and partway through her college degree at the time of publication. An initial chronological structure later turns more thematic and the topics are perhaps a little scattershot. I would attribute this, at least in part, to the method of composition: it would be difficult to make large-scale edits on a manuscript because everything she typed had to be spelled back to her for approval. Minor line edits would be easy enough, but not big structural changes. (I wonder if it’s similar with work that’s been dictated, like May Sarton’s later journals.)

Helen Keller in graduation cap and gown. (PPOC, Library of Congress. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.)

Keller went on to write 12 more books. It would be interesting to follow up with another one to learn about her travels and philanthropic work. For insight into a different aspect of her life – bearing in mind that it’s fiction – I recommend Helen Keller in Love by Rosie Sultan. In a couple of places Keller mentions Laura Bridgman, her less famous predecessor in the deaf–blind community; Kimberly Elkins’ 2014 What Is Visible is a stunning novel about Bridgman.

For such a concise book – running to just 75 pages in my Dover Thrift Editions paperback – this packs in so much. Indeed, I’ve found more to talk about in this review than I might have expected. The elements that most intrigued me were her early learning about abstractions like love and thought, and her enthusiastic rundown of her favorite books: “In a word, literature is my Utopia. Here I am not disenfranchised. No barrier of the senses shuts me out from the sweet, gracious discourse of my book-friends.”

It’s possible some readers will find her writing style old-fashioned. It would be hard to forget you’re reading a work from nearly 120 years ago, given the sentimentality and religious metaphors. But the book moves briskly between anecdotes, with no filler. I remained absorbed in Keller’s story throughout, and so admired her determination to obtain a quality education. I know we’re not supposed to refer to disabled authors’ work as “inspirational,” so instead I’ll call it both humbling and invigorating – a reminder of my privilege and of the force of the human will. (Secondhand purchase, Barter Books)

Also reviewed by:

Keep in touch via Twitter (@bookishbeck / @cathy746books) and Instagram (@bookishbeck / @cathy_746books). We’ll add any of your review links in to our master posts. Feel free to use the terrific feature image Cathy made and don’t forget the hashtag #NovNov.

Novellas in November (#NovNov) Begins! Leave Your Links Here

I always look forward to November’s reading. Since 2016 I’ve been prioritizing novellas in this month, but this is only the second year that Cathy of 746 Books and I have co-hosted Novellas in November as a proper reading challenge.

We have four weekly prompts and “buddy reads” as below. We hope you’ll join in reading one or more of these with us. The host for the week will aim to publish her review on the Thursday, but feel free to post yours at any time in the month. (A reminder that we suggest 150–200 pages as the upper limit for a novella, and post-1980 for the contemporary week.)

1–7 November: Contemporary fiction (Cathy)

Open Water by Caleb Azumah Nelson – including a giveaway of a signed copy!

8–14 November: Short nonfiction (Rebecca)

The Story of My Life by Helen Keller (free to download here from Project Gutenberg. Note: only the first 85 pages constitute her memoir; the rest is letters and supplementary material.)

15–21 November: Literature in translation (Cathy)

Territory of Light by Yuko Tsushima

22–28 November: Short classics (Rebecca)

Ethan Frome by Edith Wharton (free to download here from Project Gutenberg)

Leave links to any of your novellas coverage in the comments below or tag us on Twitter (@bookishbeck / @cathy746books) and/or Instagram (@bookishbeck / @cathy_746books) and we’ll add them to a master list.

Enjoy your reading!

Ongoing list of Novellas in November 2021 posts:

Five novellas: de Kat, Lynch, Mingarelli, Sjón, Terrin (reviewed by Susan at A life in books)

The Fell by Sarah Moss (reviewed by Dr Laura Tisdall)

The Disinvent Movement by Susanna Gendall (reviewed by Lisa at ANZ LitLovers)

Four novellas with screen adaptations (a list by Diana at Ripple Effects)

Contemporary novellas from the archives (a list by Annabel at Annabookbel)

Moral Hazard by Kate Jennings (reviewed by Cathy at 746 Books)

A Child in the Theatre by Rachel Ferguson (reviewed by Simon at Stuck in a Book)

The Death of the Author by Gilbert Adair (reviewed by Karen at Kaggsy’s Bookish Ramblings)

Come Closer by Sara Gran (reviewed by Cathy at 746 Books)

Amsterdam by Ian McEwan (reviewed by Simon at Stuck in a Book)

Five novellas: Burley, Capote, Hill, Steinbeck, Welsh (reviewed by Margaret at BooksPlease)

Often I Am Happy by Jens Christian Grøndahl (reviewed by Simon at Stuck in a Book)

Vertigo by Amanda Lohrey (reviewed by Nancy Elin)

Open Water by Caleb Azumah Nelson (reviewed by Cathy at 746 Books)

Open Water & Other Contemporary Novellas Read This Year

An Island by Karen Jennings (reviewed by Lisa at ANZ LitLovers)

At Night All Blood Is Black by David Diop (reviewed by Anokatony at Tony’s Book World)

Stone in a Landslide by Maria Barbal (reviewed by Karen at BookerTalk)

A Whole Life by Robert Seethaler (reviewed by Imogen at Reading and Watching the World)

I’m Ready Now by Nigel Featherstone (reviewed by Nancy Elin)

Small Things Like These by Claire Keegan (reviewed by Cathy at 746 Books)

The Lonely by Paul Gallico (reviewed by Simon at Stuck in a Book)

The Love Child by Edith Olivier (reviewed by Liz at Adventures in reading, running and working from home)

Murder Included by Joanna Cannan (reviewed by Simon at Stuck in a Book)

The Bookshop by Penelope Fitzgerald: From Novella to Movie (reviewed by Diana at Ripple Effects)

The River by Rumer Godden (reviewed by Lisa at ANZ LitLovers)

The Rector and The Doctor’s Family by Mrs Oliphant (reviewed by Liz at Adventures in reading, running and working from home)

Less than Zero by Bret Easton Ellis (reviewed by Kate at Books Are My Favourite and Best)

Open Water by Caleb Azumah Nelson (reviewed by Laura at Reading in Bed)

Foe by J.M. Coetzee (reviewed by Lisa at ANZ LitLovers)

The Writer’s Cats by Muriel Barbery (reviewed by Davida at TCL Book Reviews)

Short Non-fiction from the archives (a list by Annabel at Annabookbel)

Nonfiction November: Book Pairing – Novellas and Nonfiction (a list by Cathy at 746 Books)

Casanova’s Homecoming by Arthur Schnitzler (reviewed by Marina Sofia at Finding Time to Write)

Which Way? by Theodora Benson (reviewed by Liz at Adventures in reading, running and working from home)

Short Memoirs by Lucille Clifton, Alice Thomas Ellis and Deborah Levy

Aimez-vous Brahms? by Françoise Sagan (reviewed by Lisa at ANZ LitLovers)

The Writer’s Cats by Muriel Barbery (reviewed by Annabel at Annabookbel)

Burning Secret by Stefan Zweig (reviewed by Chris at Calmgrove)

The Cost of Living by Deborah Levy (reviewed by Cathy at 746 Books)

The Birds of the Innocent Wood by Deirdre Madden (reviewed by Simon at Stuck in a Book)

Baron Bagge by Alexander Lernet-Holenia (reviewed by Grant at 1streading)

The Poor Man by Stella Benson (reviewed by Simon at Stuck in a Book)

Somebody Loves You by Mona Arshi (reviewed by Davida at TCL Book Reviews)

Short Nature Books by John Burnside, Jim Crumley and Aimee Nezhukumatathil

Hiroshima by John Hersey (reviewed by Cathy at 746 Books)

Short nonfiction by Athill, Herriot and Mantel (reviewed by Margaret at BooksPlease)

The Fell by Sarah Moss (reviewed by Susan at A life in books)

The Story of Stanley Brent by Elizabeth Berridge (reviewed by Simon at Stuck in a Book)

The Parakeeting of London by Nick Hunt and Tim Mitchell (reviewed by Liz at Adventures in reading, running and working from home)

The Story of My Life by Helen Keller

Taking a Look Back at Novellas Read in 2021 (a list by JDC at Gallimaufry Book Studio)

Small Things Like These by Claire Keegan (a review by Mairead at Swirl and Thread)

The Story of My Life by Helen Keller (reviewed by Cathy at 746 Books)

The Faces by Tove Ditlevsen (reviewed by Anokatony at Tony’s Book World)

Coda by Thea Astley (reviewed by Nancy Elin)

I’d Rather Be Reading by Anne Bogel (reviewed by Karen at The Simply Blog)

Notes from an Island by Tove Jansson (reviewed by Simon at Stuck in a Book)

The Fell by Sarah Moss (reviewed by Clare at Years of Reading Selfishly)

Small Things Like These by Claire Keegan (reviewed by Susan at A life in books)

The Looking Glass by Carla Sarett (reviewed by Davida at TCL Book Reviews)

Daisy Miller by Henry James (reviewed by Diana at Thoughts on Papyrus)

Heritage by Vita Sackville-West (reviewed by Simon at Stuck in a Book)

One Billion Years to the End of the World by Arkady and Boris Strugatsky (reviewed by Chris at Calmgrove)

The Sense of an Ending by Julian Barnes (reviewed by Tracy at Bitter Tea and Mystery)

We Kill Stella by Marlen Haushofer and Come Closer by Sara Gran (reviewed by Marina Sofia at Finding Time to Write)

Tea and Sympathetic Magic by Tansy Rayner Roberts (reviewed by Nancy Elin)

Passing by Nella Larsen, from Novella to Screen (reviewed by Diana at Ripple Effects)

The Employees by Olga Ravn and A Psalm for the Wild-Built by Becky Chambers (reviewed by Annabel at Annabookbel)

Maigret in Court by Georges Simenon (reviewed by Karen at BookerTalk)

No. 91/92: A Diary of a Year on the Bus by Lauren Elkin (reviewed by Rebecca at Reading Indie)

Six Scottish Novellas: Gray, Mackay Brown, Mitchison, Muir, Owens, Smith (reviewed by Grant at 1streading)

Cain by José Saramago (reviewed by Lisa at ANZ LitLovers)

The Pear Field by Nana Ekvtimishvili (Booktube review by Jennifer at Insert Literary Pun Here)

Tinkers by Paul Harding (reviewed by Simon at Stuck in a Book)

Concrete by Thomas Bernhard (reviewed by Emma at Book Around the Corner)

Frida Kahlo and My Left Leg by Emily Rapp Black (reviewed by Imogen at Reading and Watching the World)

Utility Furniture by Jon Mills (reviewed by Liz at Adventures in reading, running and working from home)

Symposium by Muriel Spark (reviewed by Chris at Calmgrove)

Griffith Review #66, The Light Ascending, annual Novella Project edition (reviewed by Lisa at ANZ LitLovers)

SixforSunday: Novellas Read in 2021 before November (reviewed by Davida at TCL Book Reviews)

The Silent Traveller in Oxford by Chiang Yee (reviewed by Simon at Stuck in a Book)

The War of the Poor by Éric Vuillard (reviewed by Lisa at ANZ LitLovers)

The Spoke by Friedrich Glauser (reviewed by Marina Sofia at Finding Time to Write)

Dinner by César Aira (reviewed by Cathy at 746 Books)

The Scrolls from the Dead Sea by Edmund Wilson (reviewed by Reese at Typings)

The Story of My Life by Helen Keller (reviewed by Laura at Reading in Bed)

The White Riband by F. Tennyson Jesse (reviewed by Simon at Stuck in a Book)

Translated fiction novellas from the archives, including Territory of Light by Yuko Tsushima (reviewed by Annabel at Annabookbel)

I Don’t Want to Go to the Taj Mahal by Charlie Hill (reviewed by Liz at Adventures in reading, running and working from home)

Miss Peabody’s Inheritance by Elizabeth Jolley (reviewed by Karen at BookerTalk)

Hotel Iris by Yoko Ogawa (reviewed by Cathy at 746 Books)

Crusade by Amos Oz (reviewed by Nancy Elin)

Barbarian Spring by Jonas Lüscher (reviewed by Marina Sofia at Finding Time to Write)

My Monticello by Jocelyn Nicole Johnson (reviewed by Susan at A life in books)

The Fell by Sarah Moss (reviewed by Eric at Lonesome Reader)

Winter Flowers by Angélique Villeneuve (reviewed by Cathy at 746 Books)

Particularly Cats by Doris Lessing (reviewed by Simon at Stuck in a Book)

Territory of Light by Yuko Tsushima

Territory of Light by Yuko Tsushima (reviewed by Cathy at 746 Books)

The Murder Farm by Andrea Maria Schenkel and The Peacock by Isabel Bogdan (reviewed by Annabel at Annabookbel)

Assembly by Natasha Brown (reviewed at Radhika’s Reading Retreat)

Ludmilla by Paul Gallico (reviewed by Simon at Stuck in a Book)

The Woman from Uruguay by Pedro Mairal (reviewed by Susan at A life in books)

An interview with Stella Sabin of Peirene Press (by Cathy at 746 Books)

Behind the Mask by Kate Walter

The Pigeon and The Appointment

In the Company of Men and Winter Flowers

Who Was Changed and Who Was Dead by Barbara Comyns

The Deal of a Lifetime by Fredrik Backman (reviewed by Karen at The Simply Blog)

Carte Blanche by Carlo Lucarelli (reviewed by Tracy at Bitter Tea and Mystery)

Inspector Chopra & the Million Dollar Motor Car by Vaseem Khan (reviewed by Chris at Calmgrove)

Bunner Sisters by Edith Wharton (reviewed by Diana at Ripple Effects)

Father Malachy’s Miracle by Bruce Marshall (reviewed by Simon at Stuck in a Book)

Ignorance by Milan Kundera (reviewed by Simon at Stuck in a Book)

Rider on the Rain by Sébastien Japrisot and The Saint-Fiacre Affair by Georges Simenon (reviewed by Annabel at Annabookbel)

Hotel Splendid by Marie Redonnet and Fear by Stefan Zweig (reviewed by Cathy at 746 Books)

Some classics from my archives (reviewed by Annabel at Annabookbel)

The Cardinals by Bessie Head (reviewed by Marina Sofia at Finding Time to Write)

These Lifeless Things by Premee Mohamed, A Psalm for the Wild-Built by Becky Chambers, The Deep by Rivers Solomon (reviewed by Dr Laura Tisdall)

Four novellas, four countries, four decades (reviewed by Emma at Book Around the Corner)

Daphnis and Chloe by Longus (reviewed by Reese at Typings)

The Invisible Host by Gwen Bristow and Bruce Manning (reviewed by Simon at Stuck in a Book)

In Youth Is Pleasure by Denton Welch (reviewed by Imogen at Reading and Watching the World)

The Newspaper of Claremont Street by Elizabeth Jolley (reviewed by Nancy Elin)

Six Short Cat Books: Muriel Barbery, Garfield and More

Catholics by Brian Moore (reviewed by Cathy at 746 Books)

I’d Rather Be Reading by Anne Bogel (reviewed by Simon at Stuck in a Book)

A River in Darkness by Masaji Ishikawa (reviewed by Karen at BookerTalk)

The Witch of Clatteringshaws by Joan Aiken (reviewed by Chris at Calmgrove)

The Old Man and the Sea by Ernest Hemingway (reviewed by Margaret at BooksPlease)

The Turn of the Screw by Henry James (reviewed by Cathy at 746 Books)

Three to See the King by Magnus Mills (reviewed by Simon at Stuck in a Book)

Ethan Frome by Edith Wharton (reviewed by Cathy at 746 Books)

Touring the Land of the Dead by Maki Kashimada and Stranger Faces by Namwali Serpell (reviewed by Dr Laura Tisdall)

Ethan Frome by Edith Wharton (reviewed by Davida at TCL Book Reviews)

Love by Angela Carter (reviewed by Simon at Stuck in a Book)

Picnic at Hanging Rock by Joan Lindsay (reviewed by Margaret at BooksPlease)

Novellas in November 2021 Wrap Up (by Carol at Reading Ladies)

A Guide to Modernism in Metroland by Joshua Abbott and Black London by Avril Nanton and Jody Burton (reviewed by Liz at Adventures in reading, running and working from home)

Ethan Frome by Edith Wharton (reviewed by Karen at The Simply Blog)

Signs Preceding the End of the World by Yuri Herrera (reviewed by Karen at BookerTalk)

Madonna in a Fur Coat by Sabahattin Ali (reviewed by Imogen at Reading and Watching the World)

Small Things Like These by Claire Keegan (reviewed by Davida at TCL Book Reviews)

Clara’s Daughter by Meike Ziervogel (reviewed by Chris at Calmgrove)

Breakfast at Tiffany’s: from Novella to Screen (reviewed by Diana at Ripple Effects)

Child of All Nations by Irmgard Keun (reviewed by Marina Sofia at Finding Time to Write)

Territory of Light by Yuko Tsushima (reviewed by Laura at Reading in Bed)

Three Contemporary Novellas: Moss, Brown and Gaitskill (reviewed by Cathy at 746 Books)

Seven Final Novellas: Crumley, Morris, Rapp Black; Hunter, Johnson, Josipovici, Otsuka

In Pious Memory by Margery Sharp (reviewed by HeavenAli)

Murder in the Dark by Margaret Atwood, The Story of Stanley Brent by Elizabeth Berridge, Under the Tripoli Sky by Kamal Ben Hameda (reviewed by HeavenAli)

The Penelopiad by Margaret Atwood (reviewed by She Reads Novels)

Caravan Story by Wayne Macauley (reviewed by Lisa at ANZ LitLovers)

Farmer Giles of Ham by J.R.R. Tolkien (reviewed by Lisa at ANZ LitLovers)

I Am God, a Novel by Giacomo Sartori (reviewed by Lisa at ANZ LitLovers)

White Fragility by Robin DiAngelo (reviewed by Liz at Adventures in reading, running and working from home)

The Aunt Who Wouldn’t Die by Shirshendu Mukhopadhyay (reviewed by Erdeaka at The Bookly Purple)

Second-Class Citizen by Buchi Emecheta (reviewed by Liz at Adventures in reading, running and working from home)

The Invention of Morel by Adolfo Bioy Casares (reviewed by Emma at Words and Peace)

The Fell by Sarah Moss (reviewed by Callum McLaughlin)

Women & Power by Mary Beard and Come Closer by Sara Gran (reviewed by Callum McLaughlin)

The Tobacconist by Robert Seethaler and I Was Jack Mortimer by Alexander Lernet-Holenia (reviewed by Madame Bibi Lophile)

Things I Don’t Want to Know and The Cost of Living by Deborah Levy (reviewed by Madame Bibi Lophile)

Touch the Water, Touch the Wind by Amos Oz (reviewed by Kim at Reading Matters)

The Woman in the Blue Cloak by Deon Meyer (reviewed by Kim at Reading Matters)

The White Woman by Liam Davison (reviewed by Kim at Reading Matters)

Boys Don’t Cry by Fiona Scarlett (reviewed by Kim at Reading Matters)

Fludd by Hilary Mantel (reviewed by Margaret at BooksPlease)

Pietr the Latvian by Georges Simenon (reviewed by Margaret at BooksPlease)

In Translation by Annamarie Jagose (reviewed by Lisa at ANZ LitLovers)

The Red Chesterfield by Wayne Arthurson, The Book of Eve by Constance Beresford-Howe, Tower by Frances Boyle, Winter Wren by Theresa Kishkan, and The Santa Rosa Trilogy by Wendy McGrath (reviewed by Naomi at Consumed by Ink)

An essay on Kate Jennings’ Snake (reviewed by Whispering Gums)

Life in Translation by Anthony Ferner and Friend Indeed by Katharine d’Souza (reviewed by Liz at Adventures in reading, running and working from home)

Every Day Is Gertie Day by Helen Meany (reviewed by Whispering Gums)

Cold Enough for Snow by Jessica Au (reviewed by Brona’s Books at This Reading Life)

A Dream Life by Claire Messud (reviewed by Brona’s Books at This Reading Life)

Why Do I Like Novellas? Barnes, Brown, Jones, Ravn (reviewed by Stargazer)

Small Things Like These by Claire Keegan (reviewed by Callum McLaughlin)

Foster by Claire Keegan (reviewed by Smithereens)

The Light in the Piazza by Elizabeth Spencer (reviewed by Anokatony at Tony’s Book World)

King City by Stephen Pennell (reviewed by Liz at Adventures in reading, running and working from home)

Missus by Ruth Park (reviewed by Lisa at ANZ LitLovers)

Inseparable by Simone de Beauvoir (reviewed by Anokatony at Tony’s Book World)

I Heard the Owl Call My Name by Margaret Craven (reviewed by Robin at A Fondness for Reading)

Maigret Defends Himself by Georges Simenon (reviewed by Chris at Calmgrove)

My Week with Marilyn by Colin Clark (reviewed by Kate at Books Are My Favourite and Best)

Ethan Frome by Edith Wharton (reviewed by Margaret at BooksPlease)

Miguel Street by V.S. Naipaul (reviewed by Liz at Adventures in reading, running and working from home)

The Swallowed Man by Edward Carey, Naturally Supernatural by Wendy Mann, The Hothouse by the East River by Muriel Spark, Trouble with Lichen by John Wyndham (reviewed by Simon at Stuck in a Book)

Ethan Frome by Edith Wharton (reviewed by Laura at Reading in Bed)

Assembly by Natasha Brown, Treacle Walker by Alan Garner, All the Devils Are Here by David Seabrook, Space Exploration by Dhara Patel (reviewed by Annabel at Annabookbel)

Bellow, Powell, Wolkers, Bomans, al-Saadawi, de Jong, Buck, Simenon, Boschwitz (reviewed by Sarah at Market Garden Reader)

October Reading Plans and Books to Catch Up On

My plans for this month’s reading include:

Autumn-appropriate titles & R.I.P. selections, pictured below.

October releases, including some poetry and the debut memoir by local nature writer Nicola Chester – some of us are going on a book club field trip to see her speak about it in Hungerford on Saturday.

October releases, including some poetry and the debut memoir by local nature writer Nicola Chester – some of us are going on a book club field trip to see her speak about it in Hungerford on Saturday.

A review book backlog dating back to July. Something like 18 books, I think? A number of them also fall into the set-aside category, below.

An alarming number of doorstoppers:

- Damnation Spring by Ash Davidson (a buddy read underway with Marcie of Buried in Print; technically it’s 442 pages, but the print is so danged small that I’m calling it a doorstopper even though my usual minimum is 500 pages)

- The Book of Form and Emptiness by Ruth Ozeki (in progress for blog review)

- Great Circle by Maggie Shipstead (a library hold on its way to me to try again now that it’s on the Booker Prize shortlist)

- The Lincoln Highway by Amor Towles (in progress for BookBrowse review)

Also, I’m aware that we’re now into the last quarter of the year, and my “set aside temporarily” shelf – which is the literal top shelf of my dining room bookcase, as well as a virtual Goodreads shelf – is groaning with books that I started earlier in the year (or, in some cases, even late last year) and for whatever reason haven’t finished yet.

Setting books aside is a dangerous habit of mine, because new arrivals, such as from the library or from publishers, and more timely-seeming books always edge them out. The only way I have a hope of finishing these before the end of the year is to a) include them in challenges wherever possible (so a few long-languishing books have gone up to join my novella stacks in advance of November) and b) reintroduce a certain number to my current stacks at regular intervals. With just 13 weeks or so remaining, two per week seems like the necessary rate.

Do you have realistic reading goals for the final quarter of the year? (Or no goals at all?)

Get Ready for Novellas in November!

Novellas: “all killer, no filler”

~Joe Hill

For the second year in a row, Cathy of 746 Books and I are co-hosting Novellas in November as a month-long challenge with four weekly prompts.

New this year: each week we will take it in turns to host a “buddy read” of a featured book we hope you will join in reading. We’re announcing the challenge early to give you plenty of time to get your stack ready.

(We suggest 150–200 pages as the upper limit for a novella, and post-1980 as a definition of “contemporary.”)

1–7 November: Contemporary fiction (Cathy)

Open Water by Caleb Azumah Nelson – including a giveaway of a signed copy!

8–14 November: Short nonfiction (Rebecca)

The Story of My Life by Helen Keller (free to download here from Project Gutenberg. Note: only the first 85 pages constitute her memoir; the rest is letters and supplementary material.)

15–21 November: Literature in translation (Cathy)

Territory of Light by Yuko Tsushima

22–28 November: Short classics (Rebecca)

Ethan Frome by Edith Wharton (free to download here from Project Gutenberg)

We’re looking forward to having you join us! Keep in touch via Twitter (@bookishbeck / @cathy746books) and Instagram (@bookishbeck / @cathy_746books) and feel free to use the terrific feature images Cathy has made and the hashtag #NovNov.

Mrs. Shields & Me: (Re)reading Carol Shields in 2020

It’s pure happenstance that I started reading Carol Shields’s work in 2006.

2005: When I first returned to England for my MA program at Leeds, I met a PhD student who was writing a dissertation on contemporary Canadian women writers. At that point I could literally name only one – Margaret Atwood – and I hadn’t even read anything by her yet.

2006: Back in the States after that second year abroad, living with my parents and killing time until my wedding, I got an evening job behind the circulation desk of the local community college library. A colleague passed on four books to me one day. By tying them up in a ribbon, she made a gift out of hand-me-downs: The Giant’s House, The Secret History, and two by Shields: Happenstance and The Stone Diaries. I’ve gone on to read most or all of the books by these authors, so I’m grateful to this acquaintance I’ve since lost touch with.

The inspiration for my post title.

Starting in June this year, I joined Marcie of Buried in Print in reading or rereading six Shields novels. She’s been rereading Shields for many years, and I benefited from her insight and careful attention to connections between the works’ characters and themes during our buddy reads. I’d treated myself to a secondhand book binge in the first lockdown, including copies of three Shields novels I’d not read before. We started with these.

Small Ceremonies (1976)

Shields’s debut ended up being my surprise favorite. A flawless novella, it brings its many elements to a satisfying conclusion and previews the author’s enduring themes in 180 pages. Judith is working on a third biography, of Susanna Moodie, and remembering the recent sabbatical year that she and her husband, a Milton scholar, spent with their two children in Birmingham. High tea is a compensating ritual she imported from a dismal England. She also brought back an idea for a novel. Meanwhile family friend Furlong Eberhardt, author of a string of twee, triumphantly Canadian novels, is casting around for plots.

What ensues is something of a sly academic comedy à la David Lodge, laced with Shields’s quiet wisdom on marriage, parenting, the writer’s vocation, and the difficulty of ever fully understanding another life. Specific links to her later work include a wonderful dinner party scene with people talking over each other and a craft project.

What ensues is something of a sly academic comedy à la David Lodge, laced with Shields’s quiet wisdom on marriage, parenting, the writer’s vocation, and the difficulty of ever fully understanding another life. Specific links to her later work include a wonderful dinner party scene with people talking over each other and a craft project.

The Box Garden (1977)

The companion novel to Small Ceremonies is narrated by Judith’s sister Charleen, a poet and single mother who lives in Vancouver and produces the National Botanical Journal. I imagined the sisters representing two facets of Shields, who had previously published poetry and a Moodie biography. Charleen is preparing to travel to Toronto for their 70-year-old mother’s wedding to Louis, an ex-priest. Via flashbacks and excruciating scenes at the family home, we learn how literally and emotionally stingy their mother has always been. If Charleen’s boyfriend Eugene’s motto is to always assume the best of people, her mother’s modus operandi is to assume she’s been hard done by.

The companion novel to Small Ceremonies is narrated by Judith’s sister Charleen, a poet and single mother who lives in Vancouver and produces the National Botanical Journal. I imagined the sisters representing two facets of Shields, who had previously published poetry and a Moodie biography. Charleen is preparing to travel to Toronto for their 70-year-old mother’s wedding to Louis, an ex-priest. Via flashbacks and excruciating scenes at the family home, we learn how literally and emotionally stingy their mother has always been. If Charleen’s boyfriend Eugene’s motto is to always assume the best of people, her mother’s modus operandi is to assume she’s been hard done by.

The title comes from the time when a faithful Journal correspondent, the mysterious Brother Adam, sent Charleen some grass seed to grow in a window box – a symbol of thriving in spite of restrictive circumstances. I thought the plot went off in a silly direction, but loved the wedding reception. Specific links to Shields’s later work include a botanical hobby, a long train journey, and a final scene delivered entirely in dialogue.

A Celibate Season (1991)

“We’re suffering a communication gap, that’s obvious.”

This epistolary novel was a collaboration: Blanche Howard wrote the letters by Jocelyn (“Jock”), who’s gone to Ottawa to be the legal counsel for a commission looking into women’s poverty, while Shields wrote the replies from her husband Charles (“Chas”), an underemployed architect who’s keeping the home fire burning back in Vancouver. He faces challenges large and small: their daughter’s first period versus meal planning (“Found the lentils. Now what?”). The household starts comically expanding to include a housekeeper, Chas’s mother-in-law, a troubled neighbor, and so on.

This epistolary novel was a collaboration: Blanche Howard wrote the letters by Jocelyn (“Jock”), who’s gone to Ottawa to be the legal counsel for a commission looking into women’s poverty, while Shields wrote the replies from her husband Charles (“Chas”), an underemployed architect who’s keeping the home fire burning back in Vancouver. He faces challenges large and small: their daughter’s first period versus meal planning (“Found the lentils. Now what?”). The household starts comically expanding to include a housekeeper, Chas’s mother-in-law, a troubled neighbor, and so on.

Both partners see how the other half lives. The misunderstandings between them become worse during their separation. Howard and Shields started writing in 1983, and the book does feel dated; they later threw in a jokey reference to the unreliability of e-mail to explain why the couple are sending letters and faxes. Two unsent letters reveal secrets Jock and Chas are keeping from each other, which felt like cheating. I remained unconvinced that so much could change in 10 months, and the weird nicknames were an issue for me. Plus, arguing about a solarium building project? Talk about First World problems! All the same, the letters are amusing.

Rereads

Happenstance (1980/1982)

This was the first novel I read by Shields. My Penguin paperback gives the wife’s story first and then you flip it over to read the husband’s story. But the opposite reflects the actual publishing order: Happenstance is Jack’s story; two years later came Brenda’s story in A Fairly Conventional Woman. The obvious inheritor of the pair is A Celibate Season with the dual male/female narratives, and the setups are indeed similar: a man is left at home alone with his teenage kids, having to cope with chores and an unexpected houseguest.

This was the first novel I read by Shields. My Penguin paperback gives the wife’s story first and then you flip it over to read the husband’s story. But the opposite reflects the actual publishing order: Happenstance is Jack’s story; two years later came Brenda’s story in A Fairly Conventional Woman. The obvious inheritor of the pair is A Celibate Season with the dual male/female narratives, and the setups are indeed similar: a man is left at home alone with his teenage kids, having to cope with chores and an unexpected houseguest.

What I remembered beforehand: The wife goes to a quilting conference; an image of a hotel corridor and elevator.

Happenstance

Jack, a museum curator in Chicago, is writing a book about “Indian” trading practices (this isn’t the word we’d use nowadays, but the terminology ends up being important to the plot). He and his best friend Bernie, who’s going through a separation, are obsessed with questions of history: what gets written down, and what it means to have a sense of the past (or not). I loved all the little threads, like Jack’s father’s obsession with self-help books, memories of Brenda’s vivacious single mother, and their neighbor’s failure as Hamlet in a local production. I also enjoyed an epic trek in the snow in a final section potentially modeled on Ulysses.

A Fairly Conventional Woman

“Aside from quiltmaking, pleasantness was her one talent. … She had come to this awkward age, forty, at an awkward time in history – too soon to be one of the new women, whatever that meant, and too late to be an old-style woman.”

Brenda is in Philadelphia for a quilting conference. Quilting, once just a hobby, is now part of a modern art movement and she earns prizes and hundreds of dollars for her pieces. The hotel is overbooked, overlapping with an International Society of Metallurgists gathering, and both she and Barry from Vancouver, an attractive metallurgist in a pinstriped suit whom she meets in the elevator, are driven from their shared rooms by roommates bringing back one-night stands. This doesn’t add anything to the picture of a marriage in Jack’s story and I only skimmed it this time. It’s a wonder I kept reading Shields after this, but I’m so glad I did!

I reviewed these last two earlier this year. They were previously my joint favorites of Shields’s work, linked by a gardening hobby, the role of chance, and the unreliability of history and (auto)biography. They remain in my top three.

The Stone Diaries (1995)

The Stone Diaries (1995)

What I remembered beforehand: a long train ride, a friend who by the feeling ‘down there’ thought that someone had had sex with her the night before, and something about the Orkney Islands.

Larry’s Party (1997)

Larry’s Party (1997)

What I remembered beforehand: a food poisoning incident (though I’d thought it was in one of Shields’s short stories), a climactic event involving a garden maze, a chapter entitled “Larry’s Penis,” and the closing dinner party scene.

Looking back: Fortunately, in the last 15 years I’ve done something to redress my ignorance, discovering Canadian women writers whom I admire greatly: Elizabeth Hay, Margaret Laurence, Mary Lawson and especially Margaret Atwood and Carol Shields.

Looking out: “I am watching. My own life will never be enough for me. It is a congenital condition, my only, only disease in an otherwise lucky life. I am a watcher, an outsider whether I like it or not, and I’m stuck with the dangers that go along with it. And the rewards.”

- That’s Judith on the last page of Small Ceremonies. It’s also probably Shields. And, to an extent, it seems like me. A writer, but mostly a reader, absorbing other lives.

Looking forward: I’m interested in rereading Shields’s short stories and Mary Swann (to be reissued by World Editions in 2021). And, though I’ve read 13 of her books now, there are still plenty of unread, lesser-known ones I’ll have to try to find secondhand one day. Her close attention to ordinary lives and relationships and the way we connect to the past makes her work essential.

Dark and carefully chiselled, the chapters are like tiny diamonds that you have to hold up to the light to see the glitter. Newly separated from her husband, the unnamed narrator, who works at a music library, entrusts us with vignettes from her first year of single parenthood. She is honest about her bad behaviour – the nights she got falling down drunk and invited men back to the apartment; the mornings she missed the daycare dropoff deadline and let her two-year-old fend for herself while she stayed in bed. Alongside the custody battle with her ex are smaller feuds, like with her neighbour, who’s had enough of the little girl dropping things onto his roof from the windows above and gets the landlord to do something about it.

Dark and carefully chiselled, the chapters are like tiny diamonds that you have to hold up to the light to see the glitter. Newly separated from her husband, the unnamed narrator, who works at a music library, entrusts us with vignettes from her first year of single parenthood. She is honest about her bad behaviour – the nights she got falling down drunk and invited men back to the apartment; the mornings she missed the daycare dropoff deadline and let her two-year-old fend for herself while she stayed in bed. Alongside the custody battle with her ex are smaller feuds, like with her neighbour, who’s had enough of the little girl dropping things onto his roof from the windows above and gets the landlord to do something about it.

This year I’ve been joining in Liz’s

This year I’ve been joining in Liz’s

As the novel opens in the 1960s, Ian Bedloe is a lazy teenager contemplating college. When his older brother Danny marries Lucy, mother to Agatha and Thomas, Ian can’t help but comment on the timing of his sister-in-law’s third pregnancy. Danny didn’t realize he’s not the father of this new baby, Daphne, and the newfound knowledge pushes him over the edge. Lucy also fails to cope, and Ian is consumed with guilt at how he inadvertently caused the collapse of their family. In an effort to atone, he joins the puritanical Church of the Second Chance and drops out of college to help his parents raise the three children. Others have to convince him that life is not just about penance and that he deserves happiness, too.

As the novel opens in the 1960s, Ian Bedloe is a lazy teenager contemplating college. When his older brother Danny marries Lucy, mother to Agatha and Thomas, Ian can’t help but comment on the timing of his sister-in-law’s third pregnancy. Danny didn’t realize he’s not the father of this new baby, Daphne, and the newfound knowledge pushes him over the edge. Lucy also fails to cope, and Ian is consumed with guilt at how he inadvertently caused the collapse of their family. In an effort to atone, he joins the puritanical Church of the Second Chance and drops out of college to help his parents raise the three children. Others have to convince him that life is not just about penance and that he deserves happiness, too.