Wellcome Book Prize Shadow Panel & Two Longlist Reviews

I’m delighted to announce the other book bloggers on my Wellcome Book Prize 2018 shadow panel: Paul Cheney of Halfman, Halfbook, Annabel Gaskell of Annabookbel, Clare Rowland of A Little Blog of Books, and Dr. Laura Tisdall. Once the shortlist is announced on Tuesday the 20th, we’ll be reading through the six nominees and sharing our thoughts. Before the official winner is announced at the end of April we will choose our own shadow winner.

I’ve been working my way through some of the longlisted titles I was able to access via the public library and NetGalley. Here’s my latest two (both  ):

):

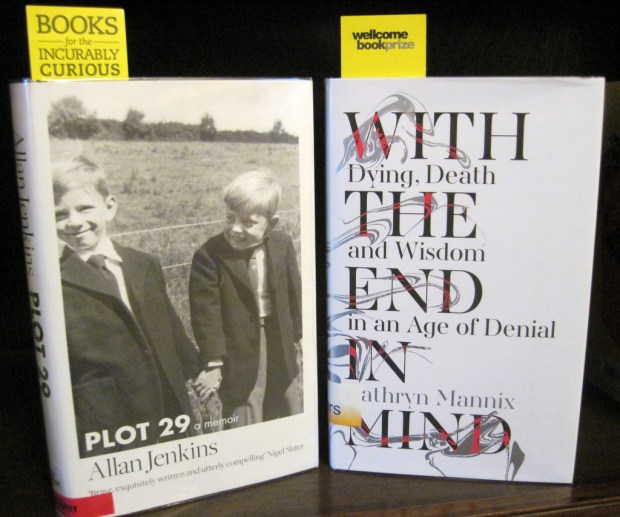

Plot 29: A Memoir by Allan Jenkins

This is an unusual hybrid memoir: it’s a meditative tour through the gardening year, on a plot in London and at his second home in his wife’s native Denmark. But it’s also the story of how Jenkins, editor of the Observer Food Monthly, investigated his early life. Handed over to a Barnardo’s home at a few months of age, he was passed between various family members and a stepfather (with some degree of neglect: his notes show scabies, rickets and TB) and then raised by strict foster parents in Devon with his beloved older half-brother, Christopher. It’s interesting to read that initially Jenkins intended to write a simple gardening diary, with a bit of personal stuff thrown in. But as he got further into the project, it started to morph.

This cover image is so sweet. It’s a photograph from Summer 1959 of Christopher and Allan (on the right, aged five), just after they were taken in by their foster parents in Devon.

The book has a complicated chronology: though arranged by month, within chapters its fragments jump around in time, a year or a date at the start helping the reader to orient herself between flashbacks and the contemporary story line. Sections are often just a paragraph long; sometimes up to a page or two. I suspect some will find the structure difficult and distancing. It certainly made me read the book slowly, which I think was the right way. You take your time adjusting to the gradual personal unveiling just as you do to the slow turn of the seasons. When major things do happen – meeting his mother in his 30s; learning who his father was in his 60s – they’re almost anticlimactic, perhaps because of the rather flat style. It’s the process that has mattered, and gardening has granted solace along the way.

I’m grateful to the longlist for making me aware of a book I otherwise might never have heard about. I don’t think the book’s mental health theme is strong enough for it to make the shortlist, but I enjoyed reading it and I’ll also take a look at Jenkins’s upcoming book, Morning, about the joys of being an early riser. (Ironic after my recent revelations about my own sleep patterns!)

Favorite lines:

“Solitude plus community, the constant I search for, the same as the allotment”

“The last element to be released from Pandora’s box, they say, was hope. So I will mourn the children we once were and I will sow chicory for bitterness. I will plant spring beans and alliums. I’ll look after them.”

“As a journalist, I have learned the five Ws – who, what, where, when, why. They are all needed to tell a story, we are taught, but too many are missing in my tale.”

With the End in Mind: Dying, Death and Wisdom in an Age of Denial by Kathryn Mannix

This is an excellent all-round guide to preparation for death. It’s based around relatable stories of the patients Mannix met in her decades working in the fields of cancer treatment and hospice care. She has a particular interest in combining CBT with palliative care to help the dying approach their remaining time with realism rather than pessimism. In many cases this involves talking patients and their loved ones through the steps of dying and explaining the patterns – decreased energy, increased time spent asleep, a change in breathing just before the end – as well as being clear about how suffering can be eased.

I read the first 20% on my Kindle and then skimmed the rest in a library copy. This was not because I wasn’t enjoying it, but because it was a two-week loan and I was conscious of needing to move on to other longlist books. It may also be because I have read quite a number of books with similar themes and scope – including Caitlin Doughty’s two books on death, Caring for the Dying by Henry Fersko-Weiss, Being Mortal by Atul Gawande, and Waiting for the Last Bus by Richard Holloway. Really this is the kind of book I would like to own a copy of and read steadily, just a chapter a week. Mannix’s introductions to each section and chapter, and the Pause for Thought pages at the end of each chapter, mean the book lends itself to being read as a handbook, perhaps in tandem with an ill relative.

The book is unique in giving a doctor’s perspective but telling the stories of patients and their families, so we see a whole range of emotions and attitudes: denial, anger, regret, fear and so on. Tears were never far from my eyes as I read about a head teacher with motor neurone disease; a pair of women with metastatic breast cancer who broke their hips and ended up as hospice roommates; a beautiful young woman who didn’t want to stop wearing her skinny jeans even though they were exacerbating her nerve pain, as then she’d feel like she’d given up; and a husband and wife who each thought the other didn’t know she was dying of cancer.

The book is unique in giving a doctor’s perspective but telling the stories of patients and their families, so we see a whole range of emotions and attitudes: denial, anger, regret, fear and so on. Tears were never far from my eyes as I read about a head teacher with motor neurone disease; a pair of women with metastatic breast cancer who broke their hips and ended up as hospice roommates; a beautiful young woman who didn’t want to stop wearing her skinny jeans even though they were exacerbating her nerve pain, as then she’d feel like she’d given up; and a husband and wife who each thought the other didn’t know she was dying of cancer.

Mannix believes there’s something special about people who are approaching the end of their life. There’s wisdom, dignity, even holiness surrounding them. It’s clear she feels she’s been honored to work with the dying, and she’s helped to propagate a healthy approach to death. As her children told her when they visited her dying godmother, “you and Dad [a pathologist] have spent a lifetime preparing us for this. No one else at school ever talked about death. It was just a Thing in our house. And now look – it’s OK. We know what to expect. We don’t feel frightened. We can do it. This is what you wanted for us, not to be afraid.”

I would be happy to see this advance to the shortlist.

Favorite lines:

“‘So, how long has she got?’ I hate this question. It’s almost impossible to answer, yet people ask as though it’s a calculation of change from a pound. It’s not a number – it’s a direction of travel, a movement over time, a tiptoe journey towards a tipping point. I give my most honest, most direct answer: I don’t know exactly. But I can tell you how I estimate, and then we can guesstimate together.”

“we are privileged to accompany people through moments of enormous meaning and power; moments to be remembered and retold as family legends and, if we get the care right, to reassure and encourage future generations as they face these great events themselves.”

Longlist strategy:

Currently reading: The Butchering Art by Lindsey Fitzharris: a history of early surgery and the fight against hospital infection, with a focus on the life and work of Joseph Lister.

Up next: I’ve requested review copies of The White Book by Han Kang and Mayhem by Sigrid Rausing, but if they don’t make it to the shortlist they’ll slip down the list of priorities.

Three Cancer Patient Memoirs

There can’t be many of us whose lives haven’t been touched by cancer. Siddhartha Mukherjee, author of The Emperor of All Maladies, estimates that one in three of us will have cancer at some point in life, and that figure is steadily rising to one in two. Cancer hit home for me in late 2010 with my brother-in-law’s diagnosis of a brain tumor and his subsequent death in early 2015. Since then I have been reading cancer and bereavement memoirs almost compulsively, looking for clues to how we can deal with this near-universal phenomenon. Here are three personal stories of cancer that have stuck with me lately.

This Is Cancer: Everything You Need to Know, from the Waiting Room to the Bedroom

By Laura Holmes Haddad

A stage IV inflammatory breast cancer survivor, Laura Holmes Haddad wrote the “What to Expect” guide she wishes she could have found at the time of her diagnosis in 2012. Throughout this comprehensive, well-structured book, she uses her own experience to set out practical advice for dealing with the everyday medical and emotional realities of cancer. On the technical side, she gives an alphabetical glossary of “Cancerspeak” vocabulary, as well as explanations of different types of scans, chemo drugs, radiation treatments, methods of coping with pain, and options for reconstruction surgery. But she also goes deep into the less obvious aspects of the disease, like hidden financial costs, little-known side effects, and complications that could affect your sleep and travel. Her tips range from the dead simple—bring your own pen for filling out hundreds of pages of forms; schedule little pick-me-ups like a mini-makeover—to major issues like marriage and parenting with cancer.

A stage IV inflammatory breast cancer survivor, Laura Holmes Haddad wrote the “What to Expect” guide she wishes she could have found at the time of her diagnosis in 2012. Throughout this comprehensive, well-structured book, she uses her own experience to set out practical advice for dealing with the everyday medical and emotional realities of cancer. On the technical side, she gives an alphabetical glossary of “Cancerspeak” vocabulary, as well as explanations of different types of scans, chemo drugs, radiation treatments, methods of coping with pain, and options for reconstruction surgery. But she also goes deep into the less obvious aspects of the disease, like hidden financial costs, little-known side effects, and complications that could affect your sleep and travel. Her tips range from the dead simple—bring your own pen for filling out hundreds of pages of forms; schedule little pick-me-ups like a mini-makeover—to major issues like marriage and parenting with cancer.

“Don’t be surprised if this thing—this cancer road trip—leads to places you never could have imagined,” Holmes Haddad writes. “I’m trying to pay it forward to other patients, to help ease some angst, to comfort.” You might be surprised to learn that this is a very pleasant read. It fluidly mixes anecdote with facts and maintains an appropriate tone: forthright and reassuring yet wry, as in the ‘Devil’s Dictionary’ type translations (“DOCTOR: ‘You might feel some discomfort.’ MEANING: ‘This will hurt like hell.’”).

No cancer patient should be without this book. That statement needs no qualifying. Yes, it might be geared more towards women, specifically breast cancer patients, and there’s some U.S.-specific information about health insurance, but much of the guidance is universally applicable. Whether for yourself or to help a family member or friend, you’ll want a copy.

My thanks to publicist Eva Zimmerman for the free e-copy for review. This Is Cancer will be released by Seal Press on Tuesday.

My rating:

Late Fragments: Everything I Want to Tell You (About This Magnificent Life)

By Kate Gross

By the end of this charming memoir, I felt I knew Kate Gross as a friend. A high-flying British civil servant who helped Tony Blair found an NGO in Africa, she was shocked to learn in her early thirties that her occasional ‘bottom trouble’ was end-stage colon cancer with liver metastases. “I’m a golden girl, a people-pleaser, something who is used to graft and a pleasant smile being rewarded,” she writes, yet here was a situation she could not control. She died at age 36 in 2014.

By the end of this charming memoir, I felt I knew Kate Gross as a friend. A high-flying British civil servant who helped Tony Blair found an NGO in Africa, she was shocked to learn in her early thirties that her occasional ‘bottom trouble’ was end-stage colon cancer with liver metastases. “I’m a golden girl, a people-pleaser, something who is used to graft and a pleasant smile being rewarded,” she writes, yet here was a situation she could not control. She died at age 36 in 2014.

In this short, clear-eyed book, she balances a brief recounting of her life with observations about terminal illness and trying to ensure a good future for her five-year-old twin sons. Memoirs by people facing death can often skirt close to cliché, but I felt Gross had fresh things to tell me about many subjects:

Cultivating “bitter gratitude”: “How strange, how brilliant it is that this awareness of wonder, this sense of the sublime, has been so closely intertwined with my illness as it has progressed.”

The value of literature: “Reading is an experience by which we connect ourselves to what we are, to this magnificent, awful life, in which the same grooves are being scored over and over again in different times and tongues.”

How to act around the dying: “we don’t expect great words of wisdom or solace. I just want this shit to be acknowledged”

Gross doesn’t believe in an afterlife beyond her children’s memory and this book—“nothingness-with-benefits.” I could sympathize with her picture of death, “me in the back of a black taxi, leaving an awesome party before the end, just when everyone else was starting to have real fun.” I wish she’d had longer at the party, but I’m glad she left these thoughts behind.

My rating:

Haematemesis: How One Man Overcame a Fear of Things Medical and Learned to Navigate His Way Around Hospital

By Henry G. Sheppard

This is a mordantly funny account of one Australian man’s experience with recurrent cancer. In remission since 2007, Sheppard discovered in 2015 that he was once more riddled—that awful word—with leukemia. Having vowed never to go through chemo again, he learned that it had somewhat improved in the intervening years, with the drip treatments now partially replaced by tablets. This time around he ran into a lot of what he calls “Big Hospital Attitude”: scheduling issues with his bone marrow biopsy, nurses who didn’t think he could manage his own insulin treatments, and constant problems with finding veins for his many injections. Was this the much-touted “Patient-Centered Care”? Would he be better off with the “quick and relatively-painless death offered when one is mauled by a pack of wild dogs”?

This is a mordantly funny account of one Australian man’s experience with recurrent cancer. In remission since 2007, Sheppard discovered in 2015 that he was once more riddled—that awful word—with leukemia. Having vowed never to go through chemo again, he learned that it had somewhat improved in the intervening years, with the drip treatments now partially replaced by tablets. This time around he ran into a lot of what he calls “Big Hospital Attitude”: scheduling issues with his bone marrow biopsy, nurses who didn’t think he could manage his own insulin treatments, and constant problems with finding veins for his many injections. Was this the much-touted “Patient-Centered Care”? Would he be better off with the “quick and relatively-painless death offered when one is mauled by a pack of wild dogs”?

“Haematemesis” means vomiting blood, and be warned: there is a lot of blood here; if you’re squeamish about needles you may struggle. There is also plenty of scatological humor. But in general I found the tone to be reminiscent of Bill Bryson in a hospital gown, especially when he’s describing squeezing his belly into a CT scanner or recounting his flatulence.

My main complaint is that at 80 pages this feels incomplete, like it’s telling just part of the story. What about his first bout with leukemia, or his earlier life (which, from a look at his Goodreads biography, seems very eventful indeed)? I understand that Sheppard wanted to get this book released while he was still able. I wish him well and hope for a sequel.

My thanks to the author for the free e-copy for review.

My rating:

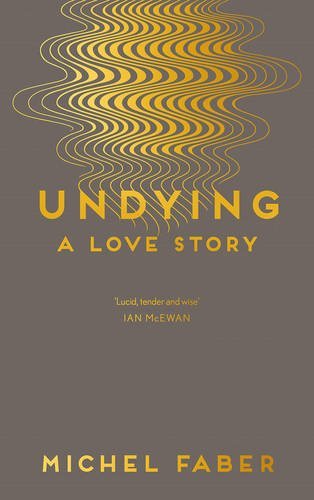

Undying: Poems by Michel Faber

Today, July 7th, happens to be my ninth wedding anniversary. For Michel Faber, however, it marks a more somber occasion: two years since his wife, Eva, died of cancer. They met in 1988 and got to spend over 25 years together. It was a second marriage for Eva, a visual artist – a bohemian life full of travel and each working on their art, until a six-year battle with multiple myeloma (a cancer of the bone marrow) cut Eva down in her fifties.

Faber’s new book, Undying: A Love Story, is a striking outpouring of 67 poems, most of them written in 2014–15, after Eva died. In two halves, it takes up first Eva’s illness and death, and then the aftermath and memories. Faber gives a vivid sense of how completely cancer changed both their lives: “There were three of us in our marriage. / You, me, and your cancer.” Eva’s illness put everything into perspective: “In our former lives, B.C., / all sorts of issues seemed to matter – / like minor wastes of money, and a scarcity / of storage space.”

Faber’s new book, Undying: A Love Story, is a striking outpouring of 67 poems, most of them written in 2014–15, after Eva died. In two halves, it takes up first Eva’s illness and death, and then the aftermath and memories. Faber gives a vivid sense of how completely cancer changed both their lives: “There were three of us in our marriage. / You, me, and your cancer.” Eva’s illness put everything into perspective: “In our former lives, B.C., / all sorts of issues seemed to matter – / like minor wastes of money, and a scarcity / of storage space.”

The poems vary widely in stanza length and style. With only a few exceptions, they are in the first person – “I” and “we” – and addressed directly to Eva as “you,” even after she was gone. In one of my favorites, “You Loved to Dance,” Faber remembers the rare occasions in their relationship when they danced together and shakes his head over lost opportunities: “A thousand chances that we didn’t take. … Half a dozen dances in a quarter-century. / I doubt you thought that that was all there’d be.”

Although this is mostly free verse, the occasional rhyming couplet ends a poem:

Yes, let us not leave off praying.

Not for God our soul to keep

but just to die, of old age, in our sleep.

Wake-up call. You’re dead another day.

The hotel hopes I have enjoyed my stay.

As you can see from those last lines, the tone is gently sardonic. Faber’s strategy is often to hold up physical artifacts of Eva’s life – the hundreds of menstrual pads she’d accumulated, only to go through early menopause (“Change Of Life”); the odd foodstuffs he found in their cupboards after her death and tried to use up (“Tamarind”) – and turn them to gently mocking commentary on all the futile plans we make. Most ironic of all is “Or, If Only,” in which he catalogues all the ways life can kill you when you don’t want it to, whereas by the end Eva longed for an easy way out: “We’d jump at any offer. / Any speedy death would do us.”

In subject matter and tone I would liken these poems to Christian Wiman’s and Christopher Reid’s. Wiman is a poet and theologian who has himself been through the trenches – long, painful years of treatment for blood cancer. Christopher Reid’s A Scattering is a poetic reflection on his wife Lucinda’s death from a brain tumor. Though you can sense the rich emotion in the poems of Undying, Faber doesn’t quite match either of these authors for craft. His talent is better suited to the expansive world of a novel like The Crimson Petal and the White.

I was thus dismayed to read in this book’s publicity materials that Faber does not intend to write any more fiction – “[Eva’s] death is a major factor in his decision not to write any further novels. A talented artist, she set aside her career to help further his, despite his protestations – and he is dedicating much of the rest of his life to making her work better known.” Faber’s The Book of Strange New Things was one of my most memorable reads from 2014. The story of an interplanetary missionary separated from his wife, it takes on new ache when you realize Faber was writing it in the shadow of his own wife’s death. If, indeed, it was to be his last novel, it’s appropriate that it gives such a poignant portrait of a marriage.

I’ll keep hoping that Faber writes more fiction. In the meantime, any fan of his writing should get hold of these tender, elegiac poems.

All I can do, in what remains of my brief time,

is mention, to whoever cares to listen,

that a woman once existed, who was kind

and beautiful and brave, and I will not forget

how the world was altered, beyond recognition,

when we met.

With thanks to Canongate for the free copy for review.

My rating:

12. The Line Becomes a River by Francisco Cantú: Francisco Cantú was a U.S. Border Patrol agent for four years in Arizona and Texas. Impressionistic rather than journalistic, his book is a loosely thematic scrapbook that, in giving faces to an abstract struggle, argues passionately that people should not be divided by walls but united in common humanity.

12. The Line Becomes a River by Francisco Cantú: Francisco Cantú was a U.S. Border Patrol agent for four years in Arizona and Texas. Impressionistic rather than journalistic, his book is a loosely thematic scrapbook that, in giving faces to an abstract struggle, argues passionately that people should not be divided by walls but united in common humanity. 11. Bookworm by Lucy Mangan: Mangan takes us along on a nostalgic chronological tour through the books she loved most as a child and adolescent. No matter how much or how little of your early reading overlaps with hers, you’ll appreciate her picture of the intensity of children’s relationship with books – they can completely shut out the world and devour their favorite stories over and over, almost living inside them, they love and believe in them so much – and her tongue-in-cheek responses to them upon rereading them decades later.

11. Bookworm by Lucy Mangan: Mangan takes us along on a nostalgic chronological tour through the books she loved most as a child and adolescent. No matter how much or how little of your early reading overlaps with hers, you’ll appreciate her picture of the intensity of children’s relationship with books – they can completely shut out the world and devour their favorite stories over and over, almost living inside them, they love and believe in them so much – and her tongue-in-cheek responses to them upon rereading them decades later. 10. Everything Happens for a Reason: And Other Lies I’ve Loved by Kate Bowler: An assistant professor at Duke Divinity School, Bowler was fascinated by the idea that you can claim God’s blessings, financial and otherwise, as a reward for righteous behavior and generosity to the church (“the prosperity gospel”), but if she’d been tempted to set store by this notion, that certainty was permanently fractured when she was diagnosed with stage IV colon cancer in her mid-thirties. Bowler writes tenderly about suffering and surrender, about living in the moment with her husband and son while being uncertain of the future.

10. Everything Happens for a Reason: And Other Lies I’ve Loved by Kate Bowler: An assistant professor at Duke Divinity School, Bowler was fascinated by the idea that you can claim God’s blessings, financial and otherwise, as a reward for righteous behavior and generosity to the church (“the prosperity gospel”), but if she’d been tempted to set store by this notion, that certainty was permanently fractured when she was diagnosed with stage IV colon cancer in her mid-thirties. Bowler writes tenderly about suffering and surrender, about living in the moment with her husband and son while being uncertain of the future. 9. Gross Anatomy by Mara Altman: Through a snappy blend of personal anecdotes and intensive research, Altman exposes the cultural expectations that make us dislike our bodies, suggesting that a better knowledge of anatomy might help us feel normal. It’s funny, it’s feminist, and it’s a cracking good read.

9. Gross Anatomy by Mara Altman: Through a snappy blend of personal anecdotes and intensive research, Altman exposes the cultural expectations that make us dislike our bodies, suggesting that a better knowledge of anatomy might help us feel normal. It’s funny, it’s feminist, and it’s a cracking good read. 8. The Unmapped Mind by Christian Donlan: Donlan, a Brighton-area video games journalist, was diagnosed with (relapsing, remitting) multiple sclerosis in 2014; he approaches his disease with good humor and curiosity, using metaphors of maps to depict himself as an explorer into uncharted territory. This is some of the best medical writing from a layman’s perspective I’ve ever read.

8. The Unmapped Mind by Christian Donlan: Donlan, a Brighton-area video games journalist, was diagnosed with (relapsing, remitting) multiple sclerosis in 2014; he approaches his disease with good humor and curiosity, using metaphors of maps to depict himself as an explorer into uncharted territory. This is some of the best medical writing from a layman’s perspective I’ve ever read. 7. Skybound by Rebecca Loncraine: For Rebecca Loncraine, after treatment for breast cancer in her early thirties, taking flying lessons in an unpowered glider (everywhere from Wales to Nepal) was a way of rediscovering joy and experiencing freedom by facing her fears in the sky. Each year seems to bring one exquisite posthumous memoir about facing death with dignity; this is a worthwhile successor to When Breath Becomes Air et al.

7. Skybound by Rebecca Loncraine: For Rebecca Loncraine, after treatment for breast cancer in her early thirties, taking flying lessons in an unpowered glider (everywhere from Wales to Nepal) was a way of rediscovering joy and experiencing freedom by facing her fears in the sky. Each year seems to bring one exquisite posthumous memoir about facing death with dignity; this is a worthwhile successor to When Breath Becomes Air et al. 6. Face to Face by Jim McCaul: Eighty percent of a facial surgeon’s work is the removal of face, mouth and neck tumors in surgeries lasting eight hours or more; McCaul also restores patients’ appearance as much as possible after disfiguring accidents. This is a book that inspires wonder at all that modern medicine can achieve.

6. Face to Face by Jim McCaul: Eighty percent of a facial surgeon’s work is the removal of face, mouth and neck tumors in surgeries lasting eight hours or more; McCaul also restores patients’ appearance as much as possible after disfiguring accidents. This is a book that inspires wonder at all that modern medicine can achieve. 5. That Was When People Started to Worry by Nancy Tucker: Tucker interviewed 70 women aged 16 to 25 for a total of more than 100 hours and chose to anonymize their stories by creating seven composite characters who represent various mental illnesses: depression, bipolar disorder, self-harm, anxiety, eating disorders, PTSD and borderline personality disorder. Reading this has helped me to understand friends’ and acquaintances’ behavior; I’ll keep it on the shelf as an invaluable reference book in the years to come.

5. That Was When People Started to Worry by Nancy Tucker: Tucker interviewed 70 women aged 16 to 25 for a total of more than 100 hours and chose to anonymize their stories by creating seven composite characters who represent various mental illnesses: depression, bipolar disorder, self-harm, anxiety, eating disorders, PTSD and borderline personality disorder. Reading this has helped me to understand friends’ and acquaintances’ behavior; I’ll keep it on the shelf as an invaluable reference book in the years to come. 4. Free Woman by Lara Feigel: A familiarity with the works of Doris Lessing is not a prerequisite to enjoying this richly satisfying hybrid of biography, literary criticism and memoir. Lessing’s The Golden Notebook is about the ways in which women compartmentalize their lives and the struggle to bring various strands into harmony; that’s what Free Woman is all about as well.

4. Free Woman by Lara Feigel: A familiarity with the works of Doris Lessing is not a prerequisite to enjoying this richly satisfying hybrid of biography, literary criticism and memoir. Lessing’s The Golden Notebook is about the ways in which women compartmentalize their lives and the struggle to bring various strands into harmony; that’s what Free Woman is all about as well. 3. Implosion by Elizabeth W. Garber: The author endured sexual and psychological abuse while growing up in a glass house designed by her father, Modernist architect Woodie Garber – a fascinating, flawed figure – outside Cincinnati in the 1960s to 1970s. This is definitely not a boring tome just for architecture buffs; it’s a masterful memoir for everyone.

3. Implosion by Elizabeth W. Garber: The author endured sexual and psychological abuse while growing up in a glass house designed by her father, Modernist architect Woodie Garber – a fascinating, flawed figure – outside Cincinnati in the 1960s to 1970s. This is definitely not a boring tome just for architecture buffs; it’s a masterful memoir for everyone. 2. Educated by Tara Westover: Westover writes with calm authority, channeling the style of the scriptures and history books that were formative in her upbringing and education as she tells of a young woman’s off-grid upbringing in Idaho and the hard work that took her from almost complete ignorance to a Cambridge PhD. This is one of the most powerful and well-written memoirs I’ve ever read.

2. Educated by Tara Westover: Westover writes with calm authority, channeling the style of the scriptures and history books that were formative in her upbringing and education as she tells of a young woman’s off-grid upbringing in Idaho and the hard work that took her from almost complete ignorance to a Cambridge PhD. This is one of the most powerful and well-written memoirs I’ve ever read. 1. Under the Rock by Benjamin Myers: A spell-bindingly lyrical book that ranges from literature and geology to true crime but has an underlying autobiographical vein. Its every sentence is well-crafted and memorable; this isn’t old-style nature writing in search of unspoiled places, but part of a growing interest in the ‘edgelands’ where human impact is undeniable but nature is creeping back in.

1. Under the Rock by Benjamin Myers: A spell-bindingly lyrical book that ranges from literature and geology to true crime but has an underlying autobiographical vein. Its every sentence is well-crafted and memorable; this isn’t old-style nature writing in search of unspoiled places, but part of a growing interest in the ‘edgelands’ where human impact is undeniable but nature is creeping back in.

A decade ago, Barbara Ehrenreich discovered a startling paradox through a Scientific American article: the immune system assists the growth and spread of tumors, including in breast cancer, which she had in 2000. It was an epiphany for her, confirming that no matter how hard we try with diet, exercise and early diagnosis, there’s only so much we can do to preserve our health; “not everything is potentially within our control, not even our own bodies and minds.” I love Ehrenreich’s Smile or Die (alternate title: Bright-Sided), which is what I call an anti-self-help book refuting the supposed health benefits of positive thinking. In that book I felt like her skeptical approach was fully warranted, and I could sympathize with her frustration – nay, outrage – when people tried to suggest she’d attracted her cancer and limited her chances of survival through her pessimism.

A decade ago, Barbara Ehrenreich discovered a startling paradox through a Scientific American article: the immune system assists the growth and spread of tumors, including in breast cancer, which she had in 2000. It was an epiphany for her, confirming that no matter how hard we try with diet, exercise and early diagnosis, there’s only so much we can do to preserve our health; “not everything is potentially within our control, not even our own bodies and minds.” I love Ehrenreich’s Smile or Die (alternate title: Bright-Sided), which is what I call an anti-self-help book refuting the supposed health benefits of positive thinking. In that book I felt like her skeptical approach was fully warranted, and I could sympathize with her frustration – nay, outrage – when people tried to suggest she’d attracted her cancer and limited her chances of survival through her pessimism.

Lents is a biology professor at John Jay College, City University of New York, and in this, his second book, he explores the ways in which the human body is flawed. These errors come in three categories: adaptations to the way the world was for early humans (to take advantage of once-scarce nutrients, we gain weight quickly – but lose it only with difficulty); incomplete adaptations (our knees are still not fit for upright walking); and the basic limitations of our evolution (inefficient systems such as the throat handling both breath and food, and the recurrent laryngeal nerve being three times longer than necessary because it loops around the aorta). Consider that myopia rates are 30% or higher, the retina faces backward, sinuses drain upwards, there are 100+ autoimmune diseases, we have redundant bones in our wrist and ankle, and we can’t produce most of the vitamins we need. Put simply, we’re not a designer’s ideal. And yet this all makes a lot of sense for an evolved species.

Lents is a biology professor at John Jay College, City University of New York, and in this, his second book, he explores the ways in which the human body is flawed. These errors come in three categories: adaptations to the way the world was for early humans (to take advantage of once-scarce nutrients, we gain weight quickly – but lose it only with difficulty); incomplete adaptations (our knees are still not fit for upright walking); and the basic limitations of our evolution (inefficient systems such as the throat handling both breath and food, and the recurrent laryngeal nerve being three times longer than necessary because it loops around the aorta). Consider that myopia rates are 30% or higher, the retina faces backward, sinuses drain upwards, there are 100+ autoimmune diseases, we have redundant bones in our wrist and ankle, and we can’t produce most of the vitamins we need. Put simply, we’re not a designer’s ideal. And yet this all makes a lot of sense for an evolved species.