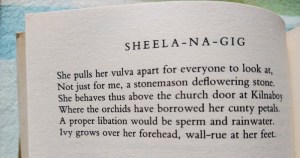

Reading Ireland Month, I: Donoghue, Longley, Tóibín

St. Patrick’s Day is a good occasion to compile my first set of contributions to Cathy’s Reading Ireland Month. Today I have an early novel by a favourite author, a poetry collection inspired by nature and mythology, and a sequel that I read for book club.

Stir-Fry by Emma Donoghue (1994)

After enjoying Slammerkin so much last year, I decided to catch up on more of Donoghue’s way-back catalogue. She tends to alternate between contemporary and historical settings. I have a slight preference for the former, but she can excel at both; it really depends on the book. I reckon this was edgy for its time. Maria (whose name rhymes with “pariah”) arrives in Dublin for university at age 17, green in every way after a religious upbringing in the countryside. In response to a flat-share advert stipulating “NO BIGOTS,” she ends up living with Ruth and Jael (pronounced “Yale”), two mature students. Ruth is the mother hen, doing all the cooking and fretting over the others’ wellbeing; Jael is a wild, henna-haired 30-year-old prone to drinking whisky by the mug-full. Maria attends lectures, takes a job cleaning office buildings, and finds a friend circle through her backstage student theatre volunteering. She’s mildly interested in American exchange student Galway and then leather-clad Damien (until she realizes he has a boyfriend), but nothing ever goes further than a kiss.

It’s obvious to readers that Ruth and Jael are a couple, but Maria doesn’t work it out until a third of the way into the book. At first she’s mortified, but soon the realization is just one more aspect of her coming of age. Maria’s friend Yvonne can’t understand why she doesn’t leave – “how can you put up with being a gooseberry?” – but Maria insists, “They really don’t make me feel left out … I think they need me to absorb some of the static. They say they’d be fighting like cats if I wasn’t around to distract them.” Scenes alternate between the flat and the campus, which Donoghue depicts as a place where radicalism and repression jostle for position. Ruth drags Maria to a Tuesday evening Women’s Group meeting that ends abruptly: “A porter put his greying head in the door to comment that they’d have to be out in five minutes, girls, this room was booked for the archaeologists’ cheese ’n’ wine.” Later, Ruth’s is the Against voice in a debate on “That homosexuality is a blot on Irish society.”

It’s obvious to readers that Ruth and Jael are a couple, but Maria doesn’t work it out until a third of the way into the book. At first she’s mortified, but soon the realization is just one more aspect of her coming of age. Maria’s friend Yvonne can’t understand why she doesn’t leave – “how can you put up with being a gooseberry?” – but Maria insists, “They really don’t make me feel left out … I think they need me to absorb some of the static. They say they’d be fighting like cats if I wasn’t around to distract them.” Scenes alternate between the flat and the campus, which Donoghue depicts as a place where radicalism and repression jostle for position. Ruth drags Maria to a Tuesday evening Women’s Group meeting that ends abruptly: “A porter put his greying head in the door to comment that they’d have to be out in five minutes, girls, this room was booked for the archaeologists’ cheese ’n’ wine.” Later, Ruth’s is the Against voice in a debate on “That homosexuality is a blot on Irish society.”

Mostly, this short novel is a dance between the three central characters. The Irish-accented banter between them is a joy. Jael’s devil-may-care attitude contrasts with Ruth and Maria’s anxiety about how they are perceived by others. Ruth and Jael are figures in the Hebrew Bible and their devotion/boldness dichotomy is applicable to the characters here, too. The stereotypical markers of lesbian identity haven’t really changed, but had Donoghue written this now I think she would at least have made Maria a year older and avoided negativity about Damien and Jael’s bisexuality. At heart this is a sweet romance and an engaging picture of early 1990s feminism, but it doesn’t completely steer clear of predictability and I would have happily taken another 50–70 pages if it meant she could have fleshed out the characters and their interactions a little more. [Guess what was for my lunch this afternoon? Stir fry!] (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com) ![]()

The Ghost Orchid by Michael Longley (1995)

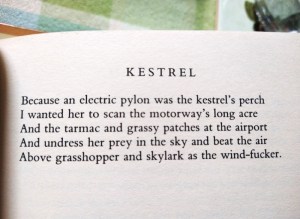

Longley’s sixth collection draws much of its imagery from nature and Greek and Roman classics. Seven poems incorporate quotations and free translations of the Iliad and Odyssey; elsewhere, he retells the story of Baucis and Philemon and other characters from Ovid. The Orient and the erotic are also major influences; references to Hokusai bookend poems about Chinese artefacts. Poppies link vignettes of the First and Second World Wars. Longley’s poetry is earthy in its emphasis on material objects and sex. Alliteration and slant rhymes are common techniques and the vocabulary is always precise. This was the third collection I’ve read by the late Belfast poet, and with its disparate topics it didn’t all cohere for me. My two favourite poems are naughty indeed:

Longley’s sixth collection draws much of its imagery from nature and Greek and Roman classics. Seven poems incorporate quotations and free translations of the Iliad and Odyssey; elsewhere, he retells the story of Baucis and Philemon and other characters from Ovid. The Orient and the erotic are also major influences; references to Hokusai bookend poems about Chinese artefacts. Poppies link vignettes of the First and Second World Wars. Longley’s poetry is earthy in its emphasis on material objects and sex. Alliteration and slant rhymes are common techniques and the vocabulary is always precise. This was the third collection I’ve read by the late Belfast poet, and with its disparate topics it didn’t all cohere for me. My two favourite poems are naughty indeed:

(Secondhand – Green Ink Booksellers, Hay-on-Wye) ![]()

Long Island by Colm Tóibín (2024)

{SPOILERS in this one}

I read Brooklyn when it first came out and didn’t revisit it (via book or film) before reading this. While recent knowledge of the first book isn’t necessary, it probably would make you better able to relate to Eilis, who is something of an emotional blank here. She’s been married for 20 years to Tony, a plumber, and is a mother to two teenagers. His tight-knit Italian American family might be considered nurturing, but for her it is more imprisoning: their four houses form an enclave and she’s secretly relieved when her mother-in-law tells her she needn’t feel obliged to join in the Sunday lunch tradition anymore.

I read Brooklyn when it first came out and didn’t revisit it (via book or film) before reading this. While recent knowledge of the first book isn’t necessary, it probably would make you better able to relate to Eilis, who is something of an emotional blank here. She’s been married for 20 years to Tony, a plumber, and is a mother to two teenagers. His tight-knit Italian American family might be considered nurturing, but for her it is more imprisoning: their four houses form an enclave and she’s secretly relieved when her mother-in-law tells her she needn’t feel obliged to join in the Sunday lunch tradition anymore.

When news comes that Tony has impregnated a married woman and the cuckolded husband plans to leave the baby on the Fiorellos’ doorstep when the time arrives, Eilis checks out of the marriage. She uses her mother’s upcoming 80th birthday as an excuse to go back to Ireland for the summer. Here Eilis gets caught up in a love triangle with publican Jim Farrell, who was infatuated with her 20 years ago and still hasn’t forgotten her, and Nancy Sheridan, a widow who runs a fish and chip shop and has been Jim’s secret lover for a couple of years. Nancy has a vision of her future and won’t let Eilis stand in her way.

I felt for all three in their predicaments but most admired Nancy’s pluck. Ironically given the title, the novel spends more of its time in Ireland and only really comes alive there. There’s also a reference to Nora Webster – cute that Tóibín is trying out the Elizabeth Strout trick of bringing multiple characters together in the same fictional community. But, all told, this was just a so-so book. I’ve read 10 or so works by Tóibín now, in all sorts of genres, and with its plain writing this didn’t stand out at all. It got an average score from my book club, with one person loving it, a couple hating it, and most fairly indifferent. (Public library) ![]()

Another batch will be coming up before the end of the month!

#NovNov23 Week 4, “The Short and the Long of It”: W. Somerset Maugham & Jan Morris

Hard to believe, but it’s already the final full week of Novellas in November and we have had 109 posts so far! This week’s prompt is “The Short and the Long of It,” for which we encourage you to pair a novella with a nonfiction book or novel that deals with similar themes or topics. The book pairings week of Nonfiction November is always a favourite (my 2023 contribution is here), so think of this as an adjacent – and hopefully fun – project. I came up with two pairs: one fiction and one nonfiction. In the first case, the longer book led me to read a novella, and it was vice versa for the second.

W. Somerset Maugham

The House of Doors by Tan Twan Eng (2023)

&

Liza of Lambeth by W. Somerset Maugham (1897)

I wasn’t a huge fan of The Garden of Evening Mists, but as soon as I heard that Tan Twan Eng’s third novel was about W. Somerset Maugham, I was keen to read it. Maugham is a reliably readable author; his books are clearly classic literature but don’t pose the stylistic difficulties I now experience with Dickens, Trollope et al. And yet I know that Booker Prize followers who had neither heard of nor read Maugham have enjoyed this equally. I’m surprised it didn’t make it past the longlist stage, as I found it as revealing of a closeted gay writer’s life and times as The Master (shortlisted in 2004) but wider in scope and more rollicking because of its less familiar setting, true crime plot and female narration.

The main action is set in 1921, as “Willie” Somerset Maugham and his secretary, Gerald, widely known to be his lover, rest from their travels in China and the South Seas via a two-week stay with Robert and Lesley Hamlyn at Cassowary House in Penang, Malaysia. Robert and Willie are old friends, and all three men fought in the First World War. Willie’s marriage to Syrie Wellcome (her first husband was the pharmaceutical tycoon) is floundering and he faces financial ruin after a bad investment. He needs a good story that will sell and gets one when Lesley starts recounting to him the momentous events of 1910, including a crisis in her marriage, volunteering at the party office of Chinese pro-democracy revolutionary Dr Sun Yat Sen, and trying to save her friend Ethel Proudlock from a murder charge.

It’s clever how Tan weaves all of this into a Maugham-esque plot that alternates between omniscient third-person narration and Lesley’s own telling. The glimpses of expat life and Asia under colonial rule are intriguing, and the scene-setting and atmosphere are sumptuous – worthy of the Merchant Ivory treatment. I was left curious to read more by and about Maugham, such as Selina Hastings’ biography. (Public library)

But for now I picked up one of the leather-bound Maugham books I got for free a few years ago. Amusingly, the novella-length Liza of Lambeth is printed in the same volume with the travel book On a Chinese Screen, which Maugham had just released when he arrived in Penang.

{SPOILERS AHEAD}

This was Maugham’s debut novel and drew on his time as a medical intern in the slums of London. In tone and content it falls almost perfectly between Dickens and Hardy, because on the one hand Liza Kemp and her neighbours are cheerful paupers even though they work in factories, have too many children and live in cramped quarters; on the other hand, alcoholism and domestic violence are rife, and the wages of sexual sin are death. All seems light to start with: an all-village outing to picnic at Chingford; pub trips; and harmless wooing as Liza rebuffs sweet Tom in favour of a flirtation with married Jim Blakeston.

At the halfway point, I thought we were going full Tess of the d’Urbervilles – how is this not a rape scene?! Jim propositions her four times, ignoring her initial No and later quiet. “‘Liza, will yer?’ She still kept silence, looking away … Suddenly he shook himself, and closing his fist gave her a violent, swinging blow in the belly. ‘Come on,’ he said. And together they slid down into the darkness of the passage.” So starts their affair, which leads to Liza getting beaten up by Mrs Blakeston in the street and then dying of an infection after a miscarriage. The most awful character is Mrs Kemp, who spends the last few pages – while Liza is literally on her deathbed – complaining of her own hardships, congratulating herself on insuring her daughter’s life, and telling a blackly comic story about her husband’s corpse not fitting in his oak coffin and her and the undertaker having to jump on the lid to get it to close.

At the halfway point, I thought we were going full Tess of the d’Urbervilles – how is this not a rape scene?! Jim propositions her four times, ignoring her initial No and later quiet. “‘Liza, will yer?’ She still kept silence, looking away … Suddenly he shook himself, and closing his fist gave her a violent, swinging blow in the belly. ‘Come on,’ he said. And together they slid down into the darkness of the passage.” So starts their affair, which leads to Liza getting beaten up by Mrs Blakeston in the street and then dying of an infection after a miscarriage. The most awful character is Mrs Kemp, who spends the last few pages – while Liza is literally on her deathbed – complaining of her own hardships, congratulating herself on insuring her daughter’s life, and telling a blackly comic story about her husband’s corpse not fitting in his oak coffin and her and the undertaker having to jump on the lid to get it to close.

Liza isn’t entirely the stereotypical whore with the heart of gold, but she is a good-time girl (“They were delighted to have Liza among them, for where she was there was no dullness”) and I wonder if she could even have been a starting point for Eliza Doolittle in Pygmalion. Maugham’s rendering of the cockney accent is over-the-top –

“‘An’ when I come aht,’ she went on, ‘’oo should I see just passin’ the ’orspital but this ’ere cove, an’ ’e says to me, ‘Wot cheer,’ says ’e, ‘I’m goin’ ter Vaux’all, come an’ walk a bit of the wy with us.’ ‘Arright,’ says I, ‘I don’t mind if I do.’”

– but his characters are less caricatured than Dickens’s. And, imagine, even then there was congestion in London:

“They drove along eastwards, and as the hour grew later the streets became more filled and the traffic greater. At last they got on the road to Chingford, and caught up numbers of other vehicles going in the same direction—donkey-shays, pony-carts, tradesmen’s carts, dog-carts, drags, brakes, every conceivable kind of wheeled thing, all filled with people”

In short, this was a minor and derivative-feeling work that I wouldn’t recommend to those new to Maugham. He hadn’t found his true style and subject matter yet. Luckily, there’s plenty of other novels to try. (Free mall bookshop) [159 pages]

Jan Morris

Conundrum by Jan Morris (1974)

&

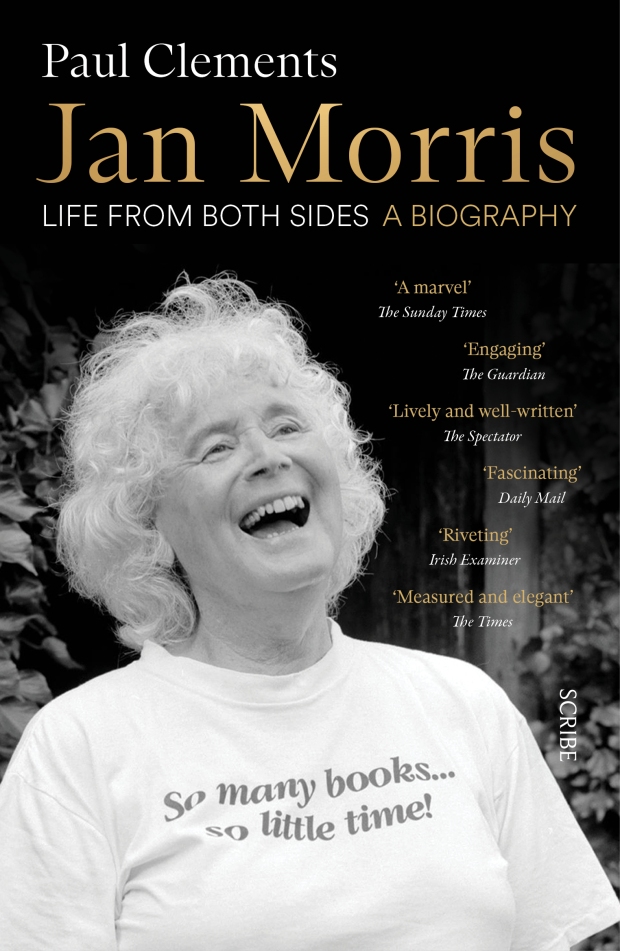

Jan Morris: Life from Both Sides, A Biography by Paul Clements (2022)

Back in 2021, I reread and reviewed Conundrum during Novellas in November. It’s a short memoir that documents her spiritual journey towards her true identity – she was a trans pioneer and influential on my own understanding of gender. In his doorstopper of a biography, Paul Clements is careful to use female pronouns throughout, even when this is a little confusing (with Morris a choirboy, a soldier, an Oxford student, a father, and a member of the Times expedition that first summited Everest). I’m just over a quarter of the way through the book now. Morris left the Times before the age of 30, already the author of several successful travel books on the USA and the Middle East. I’ll have to report back via Love Your Library on what I think of this overall. At this point I feel like it’s a pretty workaday biography, comprehensive and drawing heavily on Morris’s own writings. The focus is on the work and the travels, as well as how the two interacted and influenced her life.

Love Your Library, March 2022

Naomi has been reading a variety of books from the library, including middle grade fiction and Indigenous poetry. Rosemary and Laura posted photos of the books they’ve borrowed from their local libraries recently.

Like Laura, I’ve been sourcing prize nominees from various places. In April I hope to read two nonfiction books from the Jhalak Prize longlist (Things I Have Withheld by Kei Miller and Brown Baby by Nikesh Shukla) and two more novels from the Women’s Prize longlist (The Paper Palace by Miranda Cowley Heller and The Island of Missing Trees by Elif Shafak), and I’ve just started Colm Tóibín’s Folio Prize-winning The Magician.

All from the library: a great way to read new and critically acclaimed books without having to buy them!

I’ve joined Kay, Lynn and Naomi for the Literary Wives online book club and our first read, coming up in June, will be The Sentence by Louise Erdrich, which will be doing double duty as part of the Women’s Prize longlist. I’m in the library holds queue and my copy should come in soon. My only other Erdrich so far, Love Medicine, was a 5-star read, so I have high hopes even though the premise for this one sounds a little iffy. (A bookshop ghost – magic realism being a common denominator on this year’s list – and a Covid lockdown setting.)

I’ve joined Kay, Lynn and Naomi for the Literary Wives online book club and our first read, coming up in June, will be The Sentence by Louise Erdrich, which will be doing double duty as part of the Women’s Prize longlist. I’m in the library holds queue and my copy should come in soon. My only other Erdrich so far, Love Medicine, was a 5-star read, so I have high hopes even though the premise for this one sounds a little iffy. (A bookshop ghost – magic realism being a common denominator on this year’s list – and a Covid lockdown setting.)

For those of you who like to plan ahead, here’s our schedule thereafter. I’ll be rereading two of them (Hornby and O’Farrell) and getting four out from the library (Feito, Hurston, Medie, O’Farrell). One I’ll request as a review copy (Lee), one was 99p on Kindle (Brown), and two more remain to be found secondhand (Gaige and Hunter). Maybe there’s one or more you’d like to join in with?

September 2022 Red Island House by Andrea Lee

December 2022 State of the Union by Nick Hornby

March 2023 His Only Wife by Peace Adzo Medie

June 2023 The Harpy by Megan Hunter

September 2023 Sea Wife by Amity Gaige

December 2023 Hamnet by Maggie O’Farrell

March 2024 Mrs. March by Virginia Feito

June 2024 Recipe for a Perfect Marriage by Karma Brown

September 2024 Their Eyes Were Watching God by Zora Neale Hurston

What have you been reading or reviewing from the library recently?

Do share a link to your own post in the comments, and feel free to use the above image. I’ve co-opted a hashtag that is already popular on Twitter and Instagram: #LoveYourLibrary.

Here’s a reminder of my ideas of what you might choose to post (this list will stay up on the project page):

- Photos or a list of your latest library book haul

- An account of a visit to a new-to-you library

- Full-length or mini reviews of some recent library reads

- A description of a particular feature of your local library

- A screenshot of the state of play of your online account

- An opinion piece about library policies (e.g. Covid procedures or fines amnesties)

- A write-up of a library event you attended, such as an author reading or book club.

If it’s related to libraries, I want to hear about it!

Love Your Library, November 2021

It’s the second month of the new Love Your Library feature.

I’d like to start out by thanking all those who have taken part since last month’s post:

Adrian shared lovely stories about the libraries he’s used in Ireland, from childhood onwards.

Laila, Lori and Margaret highlighted their recent loans and reads.

Laura sent a photo of her shiny new library copy of Sally Rooney’s latest novel.

Finally, Marcie contributed this TikTok video of her library stacks!

As for my recent library experiences…

A stand-out read:

The Performance by Claire Thomas: What a terrific setup: three women are in a Melbourne theatre watching a performance of Samuel Beckett’s Happy Days. Margot is a veteran professor whose husband is developing dementia. Ivy is a new mother whose wealth hardly makes up for the devastating losses of her earlier life. Summer is a mixed-race usher concerned about her girlfriend during the fires rampaging outside the city. In rotating close third person sections, Thomas takes us into these characters’ inner worlds, contrasting their personal worries with wider issues of women’s and indigenous people’s rights and the environmental crisis, as well as with the increasingly claustrophobic scene on stage. In “The Interval,” written as a script, the main characters interact with each other, with the “forced intimacy between strangers” creating opportunities for chance meetings and fateful decisions.

The Performance by Claire Thomas: What a terrific setup: three women are in a Melbourne theatre watching a performance of Samuel Beckett’s Happy Days. Margot is a veteran professor whose husband is developing dementia. Ivy is a new mother whose wealth hardly makes up for the devastating losses of her earlier life. Summer is a mixed-race usher concerned about her girlfriend during the fires rampaging outside the city. In rotating close third person sections, Thomas takes us into these characters’ inner worlds, contrasting their personal worries with wider issues of women’s and indigenous people’s rights and the environmental crisis, as well as with the increasingly claustrophobic scene on stage. In “The Interval,” written as a script, the main characters interact with each other, with the “forced intimacy between strangers” creating opportunities for chance meetings and fateful decisions.

Doorstoppers: A problem

Aware that I’m heading to the States for Christmas on the 14th of December (only a couple of weeks from now!), I’ve started culling my library stacks, returning any books that I’m not super-keen to read before the end of the year. A few I’ll borrow another time, but most I decided weren’t actually for me, even if raved about elsewhere.

I mentioned in a post last week that I’ve had a hard time finding the concentration for doorstoppers lately, which is ironic giving how many high-profile ones there have been this year – or even just this autumn. (For example, seven of BookPage’s top 20 fiction releases of 2021 are over 450 pages.) I gave up twice on Great Circle by Maggie Shipstead, swiftly abandoned Cloud Cuckoo Land by Anthony Doerr (a silly bookish attempt at something like Cloud Atlas), didn’t have time to attempt Tenderness by Alison Macleod and The Magician by Colm Tóibín, and recently returned The Morning Star by Karl Ove Knausgaard unread.

Why so many chunky reads this year, and this season in particular? I’ve wondered if it has had something to do with the lockdown mentality – for authors or readers, or both. It can be awfully cozy, especially as winter advances (in this hemisphere), to sink into a big book. But I find that I’m always looking for an excuse to not engage with a doorstopper.

I generally enjoy the scope, detail and moral commentary of Jonathan Franzen’s novels; his previous two, Freedom and Purity, which also numbered 500+ pages, were fantastic. But Crossroads wasn’t happening for me, at least not right now. I only got to page 23 on this attempt. The Chicago setting was promising, and I’m there for the doubt and hypocrisy of church-bound characters. But with text this dense, it feels like it takes SO MANY WORDS to convey just one scene or conversation. I was finding the prose a little obnoxious, too, e.g.

I generally enjoy the scope, detail and moral commentary of Jonathan Franzen’s novels; his previous two, Freedom and Purity, which also numbered 500+ pages, were fantastic. But Crossroads wasn’t happening for me, at least not right now. I only got to page 23 on this attempt. The Chicago setting was promising, and I’m there for the doubt and hypocrisy of church-bound characters. But with text this dense, it feels like it takes SO MANY WORDS to convey just one scene or conversation. I was finding the prose a little obnoxious, too, e.g.

Of Santa the Hildebrandts had always said, Bah, humbug. And yet somehow, long past the age of understanding that presents don’t just buy and wrap themselves, he’d accepted their sudden annual appearance as, if not a miraculous provision, then a phenomenon like his bladder filling with urine, part of the normal course of things. How had he not grasped at nine a truth so obvious to him at ten? The epistemological disjunction was absolute.

Problems here: How many extra words do you need to say “He stopped believing in Santa at age 10”? When is the phrase “epistemological disjunction” ever anything other than showing off? And why did micturition present itself as an apt metaphor?

But anyway, I’ve hardly given this a fair shake yet. I daresay I’ll read it another time; it’ll be my eighth book by Franzen.

Do share a link to your own post in the comments, and feel free to use the above image. I’ve co-opted a hashtag that is already popular on Twitter and Instagram: #LoveYourLibrary.

Here’s a reminder of my ideas of what you might choose to post (this list will stay up on the project page):

- Photos or a list of your latest library book haul

- An account of a visit to a new-to-you library

- Full-length or mini reviews of some recent library reads

- A description of a particular feature of your local library

- A screenshot of the state of play of your online account

- An opinion piece about library policies (e.g. Covid procedures or fines amnesties)

- A write-up of a library event you attended, such as an author reading or book club.

If it’s related to libraries, I want to hear about it!

Memoirs by Casey Gerald and Catherine Simpson

These two memoirs may be very different in terms of the setting (Texas and Yale versus rural Lancashire) and particulars, but I’m reviewing them together because they are both about dysfunctional families and the extent to which external circumstances determine how others see us – and how we view ourselves.

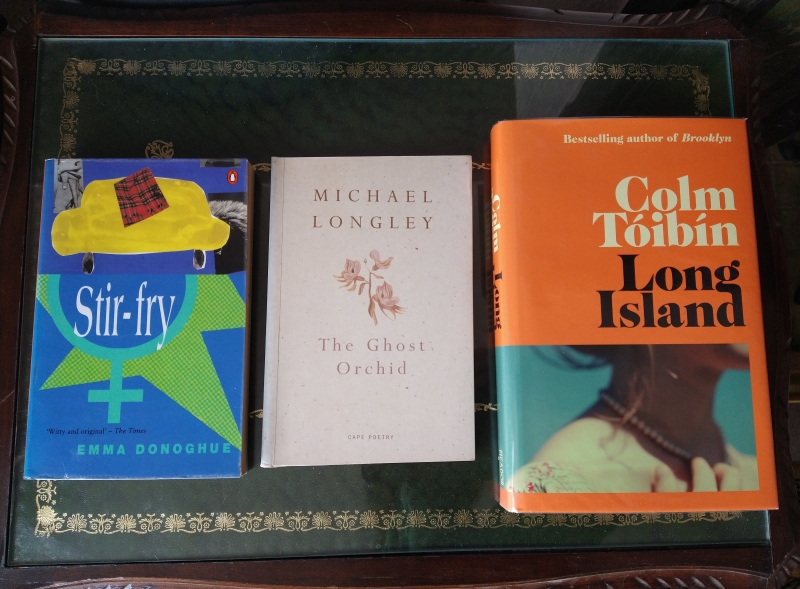

There Will Be No Miracles Here: A Memoir from the Dark Side of the American Dream by Casey Gerald (2018)

The title comes from a seventeenth-century sign in a French village that was intended to get the God-dazzled peasants back to work. For Gerald it’s a somewhat tongue-in-cheek reminder that his life, even if he has made good after an unpromising beginning, is not some American dream or fairytale. It’s more complicated than that. Still, there’s no sugar-coating his family issues. His father missed his tenth birthday party because he was next door with dope fiends; his bipolar mother was in the psych ward while his father was in jail, and then disappeared for several years. Gerald and his older sister, a college dropout, got an apartment and set their own lax rules. In the meantime, he was coming to terms with the fact that he was gay and trying to reconcile his newfound sexual identity with his Christian faith.

In spite of it all, Gerald shone academically and athletically. He was his Texas high school’s valedictorian and followed his father into a thriving college football career – at Yale, where he accidentally fell into leadership via a Men of Color council across the Ivy League schools. It wasn’t until he got to Yale that it even occurred to him that he was poor. (I was reminded of the moment in Michelle Obama’s memoir when she got to Princeton and experienced being a minority for the first time.) As he neared graduation, he decided to go into investment banking “simply because I did not have any money and none of my people had any money.” Back in Texas after a year in a Washington, D.C. think tank, he even considered a run for Congress under the slogan “We can dream again.”

In spite of it all, Gerald shone academically and athletically. He was his Texas high school’s valedictorian and followed his father into a thriving college football career – at Yale, where he accidentally fell into leadership via a Men of Color council across the Ivy League schools. It wasn’t until he got to Yale that it even occurred to him that he was poor. (I was reminded of the moment in Michelle Obama’s memoir when she got to Princeton and experienced being a minority for the first time.) As he neared graduation, he decided to go into investment banking “simply because I did not have any money and none of my people had any money.” Back in Texas after a year in a Washington, D.C. think tank, he even considered a run for Congress under the slogan “We can dream again.”

I loved the prologue, which has the 12-year-old Gerald cowering with his church congregation on the last night of 1999, in fear of being left behind at the end of the world. I think I expected religion to continue as a stronger theme throughout the book. The style wasn’t really what I imagined either: it’s a coy combination of reader address, stream-of-consciousness memories, and remembered speech in italics that often set me skimming. Whereas landmark events like his mother’s departure are left impressionistic, football games and the inner workings of Yale’s societies are described in great detail. Scenes in the classroom and with boyfriends, though still occasionally tedious, at least feel more relevant.

Gerald proudly calls himself a “faggot” and is going for a kind of sassy, folksy charm here. For me the tone only landed sometimes. Mostly I appreciated his alertness to how others (often wrongly) perceived him – a great instance of this is when he meets George W. Bush in 2007 and tells him the bare bones of his story, only for Dubya to later twist it into an example in a speech. The memoir tails off into a rather odd and sudden ending, and overall I wasn’t sure it had enough to say to fill close to 400 pages. Perhaps Gerald could have waited another 10 years? As a more successful take on similar themes, I’d recommend the memoir-in-essays Live Through This: Surviving the Intersections of Sexuality, God, and Race by Clay Cane.

My rating:

There Will Be No Miracles Here was hand-picked by Colm Tóibín for publication by Tuskar Rock Press, a new imprint of Serpent’s Tail, on January 10th. It was published in the USA by Riverhead Books in October 2018. My thanks to the UK publisher for the free copy for review.

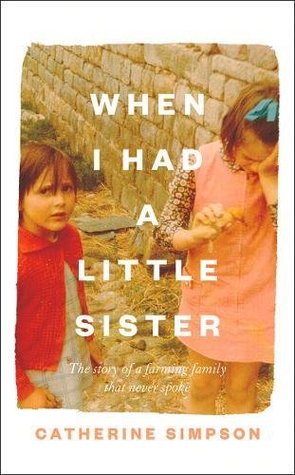

When I Had a Little Sister: The Story of a Farming Family that Never Spoke by Catherine Simpson (2019)

On December 7, 2013, Simpson’s younger sister, Tricia, was found dead by their 87-year-old father at the family farmhouse where she lived in Lancashire. She was 46 and had been receiving daily mental health visits for her bipolar disorder, but the family had never been notified about a previous suicide attempt just three weeks before. Simpson excavates her family history to ask how things could have gotten so bad that they didn’t realize that Tricia’s depression had reached suicidal levels.

Simpson’s grandparents – her grandfather a World War I veteran – moved into the property in 1925, so by this time there was literally generations’ worth of stuff to clear out. “I ask myself now: is it possible to dispose of a person’s effects with dignity?” Simpson frets. As she and her father sifted through antique furniture, gadgets and craft supplies, she recalls the previous death in the family: her mother’s from non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma seven years before. Growing up on a cattle farm in the 1970s, the three daughters were expected to be practical and unsentimental; there was never any discussion of emotions, and they got the sense that their overworked, unfulfilled mother would rather they weren’t around at all. In this context, it was hard for Tricia to cope with everyday challenges like struggling with schoolwork and the death of a beloved cousin. She started smoking at 12 and went on antidepressants at 19.

Simpson started writing this family memoir on a fellowship at Hawthornden Castle in February 2016. The first step of her project was to read all of Tricia’s diaries, from age 14 on. There were happy experiences, like six months as a nanny in Vienna and a travel grant to a kibbutz in Israel. There were also unwelcome surprises, like a 1981 suicide note – from when Tricia was just 15. Simpson had never realized just how prone her little sister was to all-or-nothing thinking. She dove headlong into short-lived relationships and, when they failed, feared she would never find love again. Over the years Tricia grew increasingly paranoid, believing she was being watched on the farm and her sisters were plotting to sell the property and leave her with nothing. One time she even locked her parents in to keep them safe.

Simpson started writing this family memoir on a fellowship at Hawthornden Castle in February 2016. The first step of her project was to read all of Tricia’s diaries, from age 14 on. There were happy experiences, like six months as a nanny in Vienna and a travel grant to a kibbutz in Israel. There were also unwelcome surprises, like a 1981 suicide note – from when Tricia was just 15. Simpson had never realized just how prone her little sister was to all-or-nothing thinking. She dove headlong into short-lived relationships and, when they failed, feared she would never find love again. Over the years Tricia grew increasingly paranoid, believing she was being watched on the farm and her sisters were plotting to sell the property and leave her with nothing. One time she even locked her parents in to keep them safe.

Although the subtitle is melodramatic, it conveys all that went unsaid in this family: not just sadness, but also love and tenderness. The cover image shows Simpson crying over a dead duckling; Tricia is at the left, her look of consternation startlingly intense for a three-year-old. “It’s only a duck. There’s plenty more where that came from” was their father’s hardhearted response. There are many other family photographs printed in black and white throughout the text; Tricia loved fashion, and is stunning in her glamour shots. While the book is probably overlong, I was absorbed in the family’s story, keen to see how Simpson would reconstruct events through objects, photographs and journals. (My sister is a Tricia, too.) Recommended to readers of Jill Bialosky’s History of a Suicide and Clover Stroud’s The Wild Other.

My rating:

When I Had a Little Sister will be published by Fourth Estate on February 7th. My thanks to the publisher for an early proof copy for review.

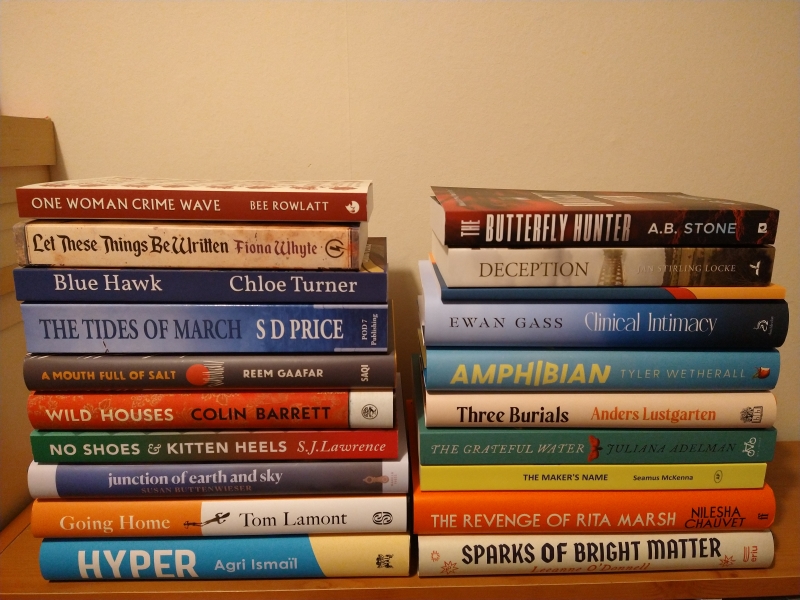

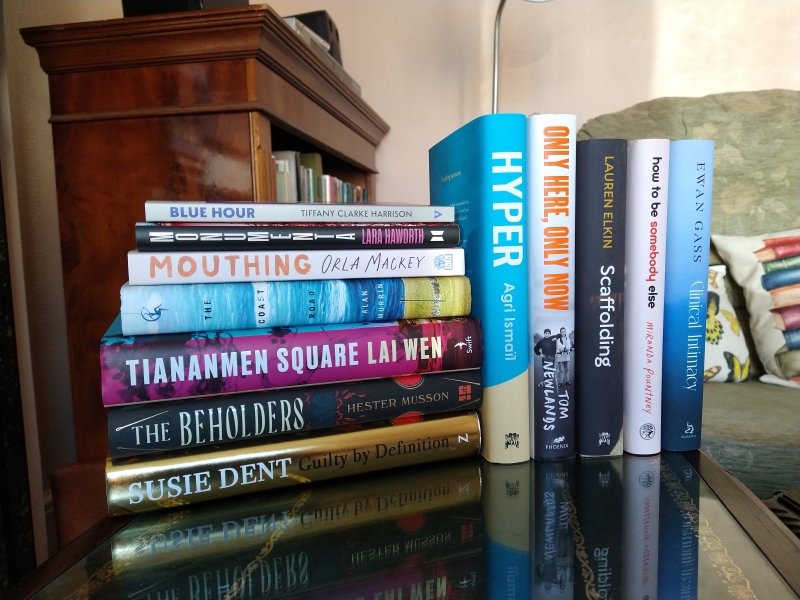

Etymology and Shakespeare studies are the keys to solving a cold case in Susie Dent’s clever, engrossing mystery, Guilty by Definition.

Etymology and Shakespeare studies are the keys to solving a cold case in Susie Dent’s clever, engrossing mystery, Guilty by Definition. Psychoanalysis, motherhood, and violence against women are resounding themes in Lauren Elkin’s Scaffolding. As history repeats itself one sweltering Paris summer, the personal and political structures undergirding the protagonists’ parallel lives come into question. This fearless, sophisticated work ponders what to salvage from the past—and what to tear down.

Psychoanalysis, motherhood, and violence against women are resounding themes in Lauren Elkin’s Scaffolding. As history repeats itself one sweltering Paris summer, the personal and political structures undergirding the protagonists’ parallel lives come into question. This fearless, sophisticated work ponders what to salvage from the past—and what to tear down. Clinical Intimacy’s mysterious antihero comes to life through interviews with his family, friends and clients. The brilliant oral history format builds a picture of isolation among vulnerable populations, only alleviated by care and touch—especially during Covid-19. Ewan Gass’s intricate story reminds us of the ultimate unknowability of other people.

Clinical Intimacy’s mysterious antihero comes to life through interviews with his family, friends and clients. The brilliant oral history format builds a picture of isolation among vulnerable populations, only alleviated by care and touch—especially during Covid-19. Ewan Gass’s intricate story reminds us of the ultimate unknowability of other people.

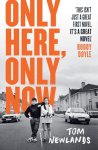

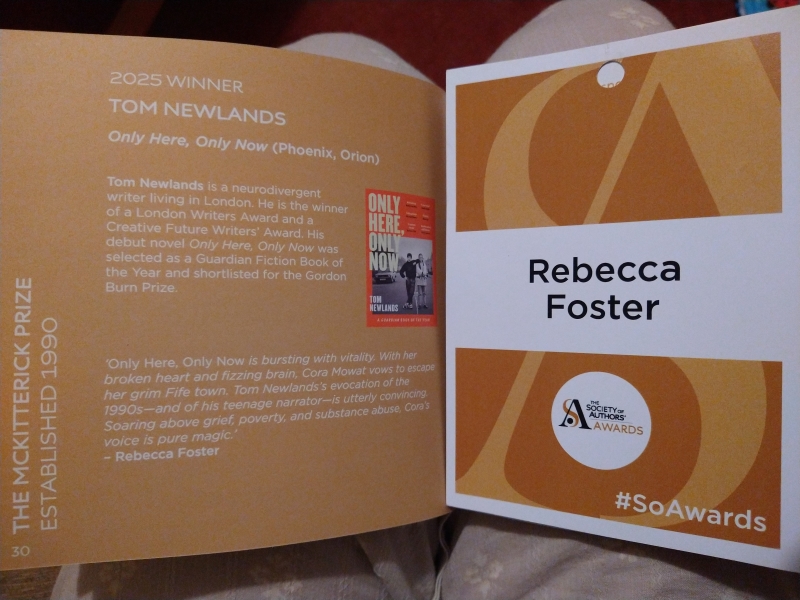

Only Here, Only Now is bursting with vitality. With her broken heart and fizzing brain, Cora Mowat vows to escape her grim Fife town. Tom Newlands’s evocation of the 1990s—and of his teenage narrator—is utterly convincing. Soaring above grief, poverty, and substance abuse, Cora’s voice is pure magic.

Only Here, Only Now is bursting with vitality. With her broken heart and fizzing brain, Cora Mowat vows to escape her grim Fife town. Tom Newlands’s evocation of the 1990s—and of his teenage narrator—is utterly convincing. Soaring above grief, poverty, and substance abuse, Cora’s voice is pure magic.

Hyper by Agri Ismaïl [I longlisted it – and then shortlisted it – but was outvoted]

Hyper by Agri Ismaïl [I longlisted it – and then shortlisted it – but was outvoted] How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney [It had two votes to make the shortlist, but because it was so similar to Scaffolding in its basics (a thirtysomething woman in a big city, the question of motherhood, and pregnancy loss) we decided to cut it.]

How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney [It had two votes to make the shortlist, but because it was so similar to Scaffolding in its basics (a thirtysomething woman in a big city, the question of motherhood, and pregnancy loss) we decided to cut it.]

All Down Darkness Wide by Seán Hewitt: This poetic memoir about love and loss in the shadow of mental illness blends biography, queer history and raw personal experience. The book opens, unforgettably, in a Liverpool graveyard where Hewitt has assignations with anonymous men. His secret self, suppressed during teenage years in the closet, flies out to meet other ghosts: of his college boyfriend; of men lost to AIDS during his 1990s childhood; of English poet George Manley Hopkins; and of a former partner who was suicidal. (Coming out on July 12th from Penguin/Vintage (USA) and July 14th from Jonathan Cape (UK). My full review is forthcoming for Shelf Awareness.)

All Down Darkness Wide by Seán Hewitt: This poetic memoir about love and loss in the shadow of mental illness blends biography, queer history and raw personal experience. The book opens, unforgettably, in a Liverpool graveyard where Hewitt has assignations with anonymous men. His secret self, suppressed during teenage years in the closet, flies out to meet other ghosts: of his college boyfriend; of men lost to AIDS during his 1990s childhood; of English poet George Manley Hopkins; and of a former partner who was suicidal. (Coming out on July 12th from Penguin/Vintage (USA) and July 14th from Jonathan Cape (UK). My full review is forthcoming for Shelf Awareness.)

The 11 stories in Erskine’s second collection do just what short fiction needs to: dramatize an encounter, or moment, that changes life forever. Her characters are ordinary, moving through the dead-end work and family friction that constitute daily existence, until something happens, or rises up in the memory, that disrupts the tedium.

The 11 stories in Erskine’s second collection do just what short fiction needs to: dramatize an encounter, or moment, that changes life forever. Her characters are ordinary, moving through the dead-end work and family friction that constitute daily existence, until something happens, or rises up in the memory, that disrupts the tedium. In form this is similar to O’Farrell’s

In form this is similar to O’Farrell’s  These autobiographical essays were compiled by Quinn based on interviews he conducted with nine women writers for an RTE Radio series in 1985. I’d read bits of Dervla Murphy’s and Edna O’Brien’s work before, but the other authors were new to me (Maeve Binchy, Clare Boylan, Polly Devlin, Jennifer Johnston, Molly Keane, Mary Lavin and Joan Lingard). The focus is on childhood: what their family was like, what drove these women to write, and what fragments of real life have made it into their books.

These autobiographical essays were compiled by Quinn based on interviews he conducted with nine women writers for an RTE Radio series in 1985. I’d read bits of Dervla Murphy’s and Edna O’Brien’s work before, but the other authors were new to me (Maeve Binchy, Clare Boylan, Polly Devlin, Jennifer Johnston, Molly Keane, Mary Lavin and Joan Lingard). The focus is on childhood: what their family was like, what drove these women to write, and what fragments of real life have made it into their books.

I didn’t realize when I started it that this was Tóibín’s debut collection; so confident is his verse that I assumed he’s been publishing poetry for decades. He’s one of those polymaths who’s written in many genres – contemporary fiction, literary criticism, travel memoir, historical fiction – and impresses in all. I’ve been finding his recent Folio Prize winner, The Magician, a little too dry and biography-by-rote for someone with no particular interest in Thomas Mann (I’ve only ever read Death in Venice), so I will likely just skim it before returning it to the library, but I can highly recommend his poems as an alternative.

I didn’t realize when I started it that this was Tóibín’s debut collection; so confident is his verse that I assumed he’s been publishing poetry for decades. He’s one of those polymaths who’s written in many genres – contemporary fiction, literary criticism, travel memoir, historical fiction – and impresses in all. I’ve been finding his recent Folio Prize winner, The Magician, a little too dry and biography-by-rote for someone with no particular interest in Thomas Mann (I’ve only ever read Death in Venice), so I will likely just skim it before returning it to the library, but I can highly recommend his poems as an alternative.

The Jasper & Scruff series by Nicola Colton: Having insisted I don’t like

The Jasper & Scruff series by Nicola Colton: Having insisted I don’t like

The Decameron Project: 29 New Stories from the Pandemic (originally published in The New York Times): Creative responses to Covid-19, ranging from the prosaic to the fantastical. I appreciated the mix of authors, some in translation and some closer to genre fiction than lit fic. Standouts were by Victor LaValle (NYC apartment neighbours; magic realism), Colm Tóibín (lockdown prompts a man to consider his compatibility with his boyfriend), Karen Russell (time stops during a bus journey), Rivers Solomon (an abused girl and her imprisoned mother get revenge), Matthew Baker (a feuding grandmother and granddaughter find something to agree on), and John Wray (a relationship starts up during quarantine in Barcelona). The best story of all, though, was by Margaret Atwood.

The Decameron Project: 29 New Stories from the Pandemic (originally published in The New York Times): Creative responses to Covid-19, ranging from the prosaic to the fantastical. I appreciated the mix of authors, some in translation and some closer to genre fiction than lit fic. Standouts were by Victor LaValle (NYC apartment neighbours; magic realism), Colm Tóibín (lockdown prompts a man to consider his compatibility with his boyfriend), Karen Russell (time stops during a bus journey), Rivers Solomon (an abused girl and her imprisoned mother get revenge), Matthew Baker (a feuding grandmother and granddaughter find something to agree on), and John Wray (a relationship starts up during quarantine in Barcelona). The best story of all, though, was by Margaret Atwood.  Allegorizings by Jan Morris: Disparate, somewhat frivolous essays written mostly pre-2009, or in 2013, and kept in trust by her publisher for publication as a posthumous collection, so strangely frozen in time. She was old but not super-old; thinking vaguely about death, but not at death’s door. The organizing principle, that everything can be understood on more than one level and so we must think beyond the literal, is interesting but not particularly applicable to the contents. There are mini travel pieces and pen portraits, but I got more out of the explorations of concepts (maturity, nationalism) and universal experiences (being caught picking one’s nose, sneezing).

Allegorizings by Jan Morris: Disparate, somewhat frivolous essays written mostly pre-2009, or in 2013, and kept in trust by her publisher for publication as a posthumous collection, so strangely frozen in time. She was old but not super-old; thinking vaguely about death, but not at death’s door. The organizing principle, that everything can be understood on more than one level and so we must think beyond the literal, is interesting but not particularly applicable to the contents. There are mini travel pieces and pen portraits, but I got more out of the explorations of concepts (maturity, nationalism) and universal experiences (being caught picking one’s nose, sneezing).

The Priory by Dorothy Whipple (read for book club): A cosy between-the-wars story, pleasant to read even though some awful things happen, or nearly happen. Like in Downton Abbey and the Cazalet Chronicles, there’s an upstairs/downstairs setup that’s appealing. It was interesting to watch how my sympathies shifted. The Persephone afterword provides useful information about the Welsh house (where Whipple stayed for a month in 1934) and family that inspired the novel. Whipple is a new author for me and I’m sure the rest of her books would be just as enjoyable, but I would only attempt another if it was significantly shorter than this one.

The Priory by Dorothy Whipple (read for book club): A cosy between-the-wars story, pleasant to read even though some awful things happen, or nearly happen. Like in Downton Abbey and the Cazalet Chronicles, there’s an upstairs/downstairs setup that’s appealing. It was interesting to watch how my sympathies shifted. The Persephone afterword provides useful information about the Welsh house (where Whipple stayed for a month in 1934) and family that inspired the novel. Whipple is a new author for me and I’m sure the rest of her books would be just as enjoyable, but I would only attempt another if it was significantly shorter than this one.

Literary prize season will soon be in full swing, and can be overwhelming. I’m currently reading Megan Nolan’s Acts of Desperation, doing double duty from the

Literary prize season will soon be in full swing, and can be overwhelming. I’m currently reading Megan Nolan’s Acts of Desperation, doing double duty from the  Today the second Barbellion Prize winner was announced: Lynn Buckle for

Today the second Barbellion Prize winner was announced: Lynn Buckle for

The Candy House by Jennifer Egan –

The Candy House by Jennifer Egan –