Wellcome Book Prize Shortlist: To Be a Machine by Mark O’Connell

The topic of this shortlisted book didn’t particularly appeal to me, so I was pleasantly surprised to enjoy it. Transhumanism is about using technology to help us overcome human limitations and radically extend our lifespan. Many of the strategies O’Connell, a Dublin-based freelance writer with a literature background, profiles are on the verge of science fiction. Are we looking at liberation from the rules of biology, or enslavement to technology? His travels take him to the heart of this very American, and very male, movement.

Cryogenic freezing: The first person was cryogenically frozen in 1966. Max More’s Alcor Life Extension Foundation in Scottsdale, Arizona offers whole-body or head-only (“neuro”) options for $200,000 or $80,000. More argues that the residents of Alcor are somewhere between living and dead. These entities are held in suspension in the belief that technology will one day allow us to upload the contents of the mind into a new vessel.

- This approach seems to conceive of the human mind/consciousness as pure information to be computed.

Cyborgs: Grindhouse Wetware, near Pittsburgh, aims to turn people into literal cyborgs. Tim Cannon had a Circadia device the size of a deck of cards implanted in his arm for three months to take biometric measurements. Other colleagues have implanted RFID chips. He intends to have his arms amputated and replaced by superior prostheses as soon as the technology is available.

Cyborgs: Grindhouse Wetware, near Pittsburgh, aims to turn people into literal cyborgs. Tim Cannon had a Circadia device the size of a deck of cards implanted in his arm for three months to take biometric measurements. Other colleagues have implanted RFID chips. He intends to have his arms amputated and replaced by superior prostheses as soon as the technology is available.

- That may seem extreme, but think how bound people already are to machines: O’Connell calls his smartphone a “mnemonic prosthesis” during his research travels.

Mortality as the enemy: Many transhumanists O’Connell meets speak of aging and death as an affront to human dignity. We mustn’t be complacent, they argue, but must oppose these processes with all we’re worth. One of the key people involved in that fight is Aubrey de Grey of SENS (“Strategies for Engineered Negligible Senescence”), and Google has also gotten in on it with their “Calico” project.

- O’Connell recounts explaining aging and death to his three-year-old son; his wife chipped in that – according to “Dada’s book” – perhaps by the time the boy is grown up death will no longer be a problem.

The Singularity: Posited by Ray Kurzweil, the Singularity is the future point at which artificial intelligence will surpass humanity. O’Connell likens it to the Christian idea of the Rapture, itself a moment of transcendence. At a conference on transhumanism and religion in Piedmont, California, he encounters Terasem, a religion founded recently by a transhumanist and transgender person.

- To my surprise, To Be a Machine makes frequent reference to religious ideas: O’Connell thinks of transhumanism as an attempt to reverse the Fall and become godlike, and he often describes the people he meets as zealots or saints, driven by the extremity of their beliefs. Both religion and transhumanism could be seen as a way of combating nihilism and insisting on the meaning of human life.

O’Connell’s outsider position helped me to engage with the science; he’s at least as interested, if not more so, in the deeper philosophical questions that transhumanism raises. I would caution that a grounding in religion and philosophy could be useful, as the points of reference used here range from the Gnostic gospels and St. Augustine to materialism and Nietzsche. But anyone who’s preoccupied with human nature should find the book intriguing.

You could also enjoy this purely as a zany travelogue along the lines of Elif Batuman’s The Possessed and Donovan Hohn’s Moby-Duck. The slapstick antics of the robots at the DARPA Robotics Challenge and the road trip in Zoltan Istvan’s presidential campaign Immortality Bus are particularly amusing. O’Connell’s Dickensian/Wildean delight in language is evident, and I also appreciated his passing references to William Butler Yeats.

It could be argued, however, that O’Connell was not the ideal author of this book. He is not naturally sympathetic to transhumanism; he’s pessimistic and skeptical, often wondering whether the proponents he meets are literally insane (e.g., to think that they are in imminent danger of being killed by robots). Most of the relevant research, even when conducted by Europeans, is going on in the USA, particularly in the Bay Area. So why would an Irish literary critic choose transhumanism as the subject for his debut? It’s a question I asked myself more than once, though it never stopped me from enjoying the book.

The title (from an Andy Warhol quote) may reference machines, but really this is about what it means to be human. O’Connell even ends with a few pages on his own cancer scare, a reminder that our bodies are flawed machines. I encourage you to give this a try even if you think you have no particular interest in technology or science fiction. It could also give a book club a lot to discuss.

Favorite lines:

“We exist, we humans, in the wreckage of an imagined splendor. It was not supposed to be this way: we weren’t supposed to be weak, to be ashamed, to suffer, to die. We have always had higher notions of ourselves. … The frailty is the thing, the vulnerability. This infirmity, this doubtful convalescence we refer to, for want of a better term, as the human condition.”

My rating:

See what the rest of the shadow panel has to say about this book:

Annabel’s review: “I loved this book from the front cover to the back, starting with its title. … He writes with empathy and a good deal of humour which makes the text always readable and entertaining, while provoking his readers to think deeply about their own beliefs.”

Clare’s review: “O’Connell’s prose style is wordy and ironic. He is pleasingly sceptical about many aspects of transhumanism. … It is an entertaining book which provides a lot of food for thought for a layperson like myself.”

Laura’s review: “Often, I found that his description of his own internal questions would mirror mine. This is a really fantastic book, and for me, a clear front runner for the Wellcome Book Prize.”

Paul’s review: “An interesting book that hopefully will provoke further discussion as we embrace technology and it envelops us.”

My gut feeling: Though they highlight opposite approaches to death – transcending it versus accepting it – this and Kathryn Mannix’s With the End in Mind seem to me the two shortlisted books of the most pressing importance. I’d be happy to see either of them win. To Be a Machine is an awful lot of fun to read, and it seems like a current favorite for our panel.

Shortlist strategy:

- I’m coming close to the end of my skim of The Vaccine Race by Meredith Wadman.

- I’m still awaiting a review copy of Mayhem by Sigrid Rausing, which I’ll be featuring as part of the official Wellcome Book Prize shortlist blog tour.

Wellcome Book Prize Shadow Panel & Two Longlist Reviews

I’m delighted to announce the other book bloggers on my Wellcome Book Prize 2018 shadow panel: Paul Cheney of Halfman, Halfbook, Annabel Gaskell of Annabookbel, Clare Rowland of A Little Blog of Books, and Dr. Laura Tisdall. Once the shortlist is announced on Tuesday the 20th, we’ll be reading through the six nominees and sharing our thoughts. Before the official winner is announced at the end of April we will choose our own shadow winner.

I’ve been working my way through some of the longlisted titles I was able to access via the public library and NetGalley. Here’s my latest two (both  ):

):

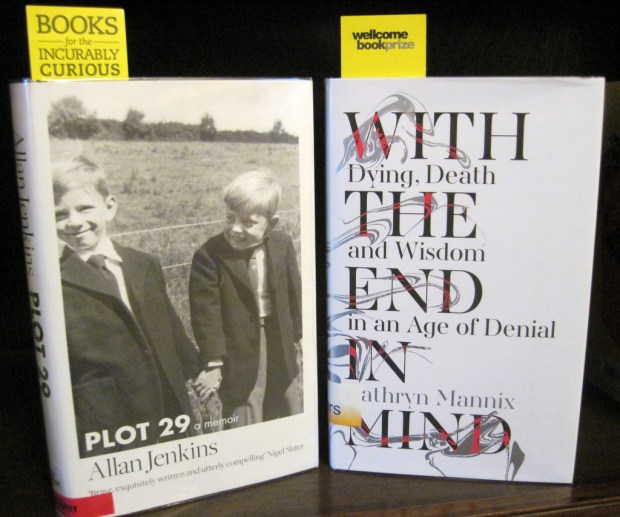

Plot 29: A Memoir by Allan Jenkins

This is an unusual hybrid memoir: it’s a meditative tour through the gardening year, on a plot in London and at his second home in his wife’s native Denmark. But it’s also the story of how Jenkins, editor of the Observer Food Monthly, investigated his early life. Handed over to a Barnardo’s home at a few months of age, he was passed between various family members and a stepfather (with some degree of neglect: his notes show scabies, rickets and TB) and then raised by strict foster parents in Devon with his beloved older half-brother, Christopher. It’s interesting to read that initially Jenkins intended to write a simple gardening diary, with a bit of personal stuff thrown in. But as he got further into the project, it started to morph.

This cover image is so sweet. It’s a photograph from Summer 1959 of Christopher and Allan (on the right, aged five), just after they were taken in by their foster parents in Devon.

The book has a complicated chronology: though arranged by month, within chapters its fragments jump around in time, a year or a date at the start helping the reader to orient herself between flashbacks and the contemporary story line. Sections are often just a paragraph long; sometimes up to a page or two. I suspect some will find the structure difficult and distancing. It certainly made me read the book slowly, which I think was the right way. You take your time adjusting to the gradual personal unveiling just as you do to the slow turn of the seasons. When major things do happen – meeting his mother in his 30s; learning who his father was in his 60s – they’re almost anticlimactic, perhaps because of the rather flat style. It’s the process that has mattered, and gardening has granted solace along the way.

I’m grateful to the longlist for making me aware of a book I otherwise might never have heard about. I don’t think the book’s mental health theme is strong enough for it to make the shortlist, but I enjoyed reading it and I’ll also take a look at Jenkins’s upcoming book, Morning, about the joys of being an early riser. (Ironic after my recent revelations about my own sleep patterns!)

Favorite lines:

“Solitude plus community, the constant I search for, the same as the allotment”

“The last element to be released from Pandora’s box, they say, was hope. So I will mourn the children we once were and I will sow chicory for bitterness. I will plant spring beans and alliums. I’ll look after them.”

“As a journalist, I have learned the five Ws – who, what, where, when, why. They are all needed to tell a story, we are taught, but too many are missing in my tale.”

With the End in Mind: Dying, Death and Wisdom in an Age of Denial by Kathryn Mannix

This is an excellent all-round guide to preparation for death. It’s based around relatable stories of the patients Mannix met in her decades working in the fields of cancer treatment and hospice care. She has a particular interest in combining CBT with palliative care to help the dying approach their remaining time with realism rather than pessimism. In many cases this involves talking patients and their loved ones through the steps of dying and explaining the patterns – decreased energy, increased time spent asleep, a change in breathing just before the end – as well as being clear about how suffering can be eased.

I read the first 20% on my Kindle and then skimmed the rest in a library copy. This was not because I wasn’t enjoying it, but because it was a two-week loan and I was conscious of needing to move on to other longlist books. It may also be because I have read quite a number of books with similar themes and scope – including Caitlin Doughty’s two books on death, Caring for the Dying by Henry Fersko-Weiss, Being Mortal by Atul Gawande, and Waiting for the Last Bus by Richard Holloway. Really this is the kind of book I would like to own a copy of and read steadily, just a chapter a week. Mannix’s introductions to each section and chapter, and the Pause for Thought pages at the end of each chapter, mean the book lends itself to being read as a handbook, perhaps in tandem with an ill relative.

The book is unique in giving a doctor’s perspective but telling the stories of patients and their families, so we see a whole range of emotions and attitudes: denial, anger, regret, fear and so on. Tears were never far from my eyes as I read about a head teacher with motor neurone disease; a pair of women with metastatic breast cancer who broke their hips and ended up as hospice roommates; a beautiful young woman who didn’t want to stop wearing her skinny jeans even though they were exacerbating her nerve pain, as then she’d feel like she’d given up; and a husband and wife who each thought the other didn’t know she was dying of cancer.

The book is unique in giving a doctor’s perspective but telling the stories of patients and their families, so we see a whole range of emotions and attitudes: denial, anger, regret, fear and so on. Tears were never far from my eyes as I read about a head teacher with motor neurone disease; a pair of women with metastatic breast cancer who broke their hips and ended up as hospice roommates; a beautiful young woman who didn’t want to stop wearing her skinny jeans even though they were exacerbating her nerve pain, as then she’d feel like she’d given up; and a husband and wife who each thought the other didn’t know she was dying of cancer.

Mannix believes there’s something special about people who are approaching the end of their life. There’s wisdom, dignity, even holiness surrounding them. It’s clear she feels she’s been honored to work with the dying, and she’s helped to propagate a healthy approach to death. As her children told her when they visited her dying godmother, “you and Dad [a pathologist] have spent a lifetime preparing us for this. No one else at school ever talked about death. It was just a Thing in our house. And now look – it’s OK. We know what to expect. We don’t feel frightened. We can do it. This is what you wanted for us, not to be afraid.”

I would be happy to see this advance to the shortlist.

Favorite lines:

“‘So, how long has she got?’ I hate this question. It’s almost impossible to answer, yet people ask as though it’s a calculation of change from a pound. It’s not a number – it’s a direction of travel, a movement over time, a tiptoe journey towards a tipping point. I give my most honest, most direct answer: I don’t know exactly. But I can tell you how I estimate, and then we can guesstimate together.”

“we are privileged to accompany people through moments of enormous meaning and power; moments to be remembered and retold as family legends and, if we get the care right, to reassure and encourage future generations as they face these great events themselves.”

Longlist strategy:

Currently reading: The Butchering Art by Lindsey Fitzharris: a history of early surgery and the fight against hospital infection, with a focus on the life and work of Joseph Lister.

Up next: I’ve requested review copies of The White Book by Han Kang and Mayhem by Sigrid Rausing, but if they don’t make it to the shortlist they’ll slip down the list of priorities.

Review: Smoke Gets in Your Eyes, by Caitlin Doughty

Caitlin Doughty, a funeral director in her early thirties, is on a mission. Her goal? Nothing less than completely changing how we think about death and the customs surrounding it. Her odyssey through the death industry began when she was 23 and started working at suburban San Francisco’s Westwind Crematorium. She had spent her first 18 years in Hawaii and saw her first dead body at age eight when she went to a Halloween costume contest at the mall and saw a little girl plummet 30 feet over a railing. In another century, she reflects, it would have been rare for a child to go that long before seeing a corpse; nineteenth-century tots might have experienced the death of multiple siblings, if not a parent.

Caitlin Doughty, a funeral director in her early thirties, is on a mission. Her goal? Nothing less than completely changing how we think about death and the customs surrounding it. Her odyssey through the death industry began when she was 23 and started working at suburban San Francisco’s Westwind Crematorium. She had spent her first 18 years in Hawaii and saw her first dead body at age eight when she went to a Halloween costume contest at the mall and saw a little girl plummet 30 feet over a railing. In another century, she reflects, it would have been rare for a child to go that long before seeing a corpse; nineteenth-century tots might have experienced the death of multiple siblings, if not a parent.

“Today, not being forced to see corpses is a privilege of the developed world,” she writes. And if we do see a dead body, it will have been so prettified by mortuary workers that it might bear little resemblance to how the person looked in life. Here Doughty reveals all the tricks of the American trade – from embalming (a post-Civil War development) and heavy-duty makeup to gluing eyes closed and sewing mouths shut – that give the dead that peaceful, lifelike look we like to see at wakes. Compare our squeamishness with the openness of various Asian countries, where one might see dozens of corpses floating down the Ganges or Buddhist monks meditating on a decomposing corpse as a memento mori.

Doughty is in a somewhat awkward position: she is part of the very American death industry she is criticizing – those “professionals whose job was not ritual but obfuscation, hiding the truths of what bodies are and what bodies do.” Although she reveled in her work at the crematorium despite its occasional gruesomeness and seems to believe cremation is an efficient and responsible choice for body disposal, she also worries that it might be a further sign of people’s determination to keep bodies out of sight and out of mind. As anthropologist Geoffrey Gorer noted, “In many cases, it would appear, cremation is chosen because it is felt to get rid of the dead more completely and finally than does burial.”

Could cremation be noble instead? Doughty traces its origins to ancient Roman funeral pyres, as different as could be from the enclosed, clinical environment of a modern crematorium. Two factors led directly to cremation becoming increasingly accepted and popular after the 1960s. One was Jessica Mitford’s book The American Way of Death (1961), which mocked the same Los Angeles area cemetery Evelyn Waugh does in The Loved One, Forest Lawn. The other was Pope Paul VI overturning the Catholic Church’s ban on cremation in 1963. Doughty quotes George Bernard Shaw’s rapturous account of his mother’s cremation in 1913 as proof that it can be not only natural, but even aesthetically pleasing:

And behold! The feet burst miraculously into streaming ribbons of garnet colored lovely flame, smokeless and eager, like Pentecostal tongues, and as the whole coffin passed in it sprang into flame all over, and my mother became that beautiful fire.

It is rare, however – and, for the workers, nerve-racking – to have witnesses at a cremation. For the most part Westwind worked like a factory, cremating six bodies per weekday. Doughty experienced all sides of the work: collecting dead fetuses from hospitals for free cremation, shaving adult corpses before burning, enduring the stench of decomposing flesh, and taking delivery of a box of heads whose bodies were donated to science. She is largely unsentimental about it all; who is this fairytale witch who speaks of “tossing” babies into the oven and grinding their little bones?

“Handmaiden to the underworld,” she describes herself, and given her medieval history degree and Goth-lite looks, you can see that a certain macabre cast of mind is necessary for this line of work. She also has a good ear for arrestingly witty one-liners; my favorite was “As a general rule, if anyone ever asks you to put stockings on a ninety-year-old deceased Romanian woman with edema, your answer should be no.”

Still, Doughty recognizes the almost unbearable sadness of many of the cases the crematorium sees – the young man who traveled to California from Washington just to stand in the path of a train, the “floaters” found in the ocean, the elderly with oozing bed sores, and the homeless folk of Los Angeles who were cremated and dumped in a mass grave after they were used for embalming practice at her mortuary school. She even considered committing suicide herself on a lonely trip out to a redwood forest.

What has kept her going is the desire to combat misconceptions and superstitions about the dead. As she realized after a potentially serious car accident on the freeway, she has lost her own fear of death, and she wants to help others do the same. This will require getting people talking about death, something she is doing through her online community Order of the Good Death and her Ask a Mortician YouTube videos. She would also like to see people having involvement with dead bodies again, as they did in previous centuries, perhaps by washing their dead relatives or keeping them at home before the funeral rather than having them taken away. “It is never too early to start thinking about your own death and the deaths of those you love.” This is not morbid; it’s just planning ahead for an inevitable experience. “We can wander further into the death dystopia, denying that we will die and hiding dead bodies from our sight. Making that choice means we will continue to be terrified and ignorant of death, and the huge role it plays in how we live our lives.”

The sections of personal anecdote in this book are better than those based on anthropological research – which is not woven in entirely naturally. Ultimately, it’s a little unclear exactly how Doughty plans to change things. She speaks of designing her own welcoming crematorium, an open, airy space that doesn’t suggest a death factory. But it’s enough that she’s part of a movement in the right direction, and beneath her wry tone her passion is clear.

Further reading suggestions: For more on how people are revolutionizing how we think about death, I highly recommend Anne Karpf’s book for the School of Life, How to Age. Other death-themed reads I have particularly enjoyed are The Undertaking by Thomas Lynch, The Removers by Andrew Meredith, and A Tour of Bones by Denise Inge. Less effective as a memoir but still interesting for its view of the funeral home business is The Undertaker’s Daughter by Kate Mayfield.

Note: I was originally going to review this book for a British website, so I received a free copy of the UK edition from Canongate. Doughty inserts British statistics and information to increase the book’s relevance to a new audience. She also astutely notes that British funerals minimize interaction with a dead body, something I have certainly found true in the two cremations I have attended in England. The Irish are famous for their wakes, but the British do not have this custom. In fact, when we attended my brother-in-law’s viewing and funeral in America earlier this year, it was the first time my husband (aged 31) had seen a dead body. Although I can see Doughty’s point about a prettified corpse not being representative of what the dead ‘should’ look like, I must also say that the funeral home had done a fantastic job of making him look happy and at peace, like he was sleeping and having pleasant dreams. He certainly didn’t look like a man who had suffered the ravages of brain cancer for four years. The same was not true for my ninety-something grandmother, however, who was nearly unrecognizable.

The subtitle – “Great Writers at the End” – gives you a hint of what to expect from this erudite, elegiac work of literary biography. In a larger sense, it is about coming to terms with the fear of death, one of the last enduring Western phobias.

The subtitle – “Great Writers at the End” – gives you a hint of what to expect from this erudite, elegiac work of literary biography. In a larger sense, it is about coming to terms with the fear of death, one of the last enduring Western phobias.

![Freud with one of his beloved cigars, 1922. Max Halberstadt [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.](https://bookishbeck.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/freud-and-cigar.jpg?w=213&h=300)

If pressed to say which books

If pressed to say which books