Tag Archives: Garrett Carr

Book Serendipity, Mid-November–Early January

This is a short set but I’ll post it now to keep things ticking over. I’ve lost nearly a week to the upper respiratory virus from hell, and haven’t felt up to sitting at my computer for any extended periods of time. I had to request extensions on a few of my work deadlines; I’ll hope to be back to normal blogging next week, too.

I call it “Book Serendipity” when two or more books that I read at the same time or in quick succession have something in common – the more bizarre, the better. This is a regular feature of mine every couple of months. Because I usually have 20–30 books on the go at once, I suppose I’m more prone to such incidents. People frequently ask how I remember all of these coincidences. The answer is: I jot them down on scraps of paper or input them immediately into a file on my PC desktop; otherwise, they would flit away! Feel free to join in with your own.

The following are in roughly chronological order.

- Ayot St Lawrence as a setting in Q’s Legacy by Helene Hanff and Flesh by David Szalay.

- A man who has panic attacks in Pan by Michael Clune and All the World Can Hold by Jung Yun.

- Two of my Shelf Awareness PRO (early) reviews in a row were of 2026 novels set on a celebrity/reunion cruise: All the World Can Hold by Jung Yun, followed by American Fantasy by Emma Straub. In both, the narrative alternates between three main characters, the cruise is to celebrate a milestone birthday for a passenger’s relative, and there’s a celebrity who’s in AA.

- A teacher–student relationship develops into a friendship in The Irish Goodbye by Beth Ann Fennelly (with Molly McCully Brown, whose Places I’ve Taken My Body I’ve reviewed) and Lessons from My Teachers by Sarah Ruhl (with Max Ritvo, about whom she wrote a whole book).

Someone becomes addicted to benzodiazepines in The Pass by Katriona Chapman and All the World Can Hold by Jung Yun (both 2026 releases).

Someone becomes addicted to benzodiazepines in The Pass by Katriona Chapman and All the World Can Hold by Jung Yun (both 2026 releases).

- A New York City event scheduled to occur on September 15 or 16, 2001 is postponed because of 9/11 in Joyride by Susan Orlean (her wedding) and All the World Can Hold by Jung Yun (a cruise departure – it’s moved to Boston).

- A 1960s attempted suicide by putting one’s head in a gas oven in The Mercy Step by Marcia Hutchinson and The Soul of Kindness by Elizabeth Taylor.

- A plan to eat cheese to induce dreams in The Reservation by Rebecca Kauffman and Slags by Emma Jane Unsworth.

- An author is (at least initially) aghast at the liberties taken with an adaptation of her book in Spent by Alison Bechdel and Joyride by Susan Orlean (the film Adaptation, one of my favourites, bears little relation to her nonfiction work The Orchid Thief, which I also love).

- A North American author meets her British publishers, André Deutsch and Diana Athill, in Book of Lives by Margaret Atwood and Q’s Legacy by Helene Hanff. (Atwood also mentions Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch, the title reference in the Hanff.)

- An older white woman feels compelled to add, as an aside after a memory of slightly dodgy behaviour observed, that cultural appropriation was not a thing in those days in Book of Lives by Margaret Atwood and Winter by Val McDermid.

- I read two books in 2025 with a title taken from a Christian Wiman poem: A Truce that Is Not Peace by Miriam Toews, then Some Bright Nowhere by Ann Packer.

- A special trip undertaken for a younger sister’s milestone birthday: a road trip through Scotland in a campervan in Slags by Emma Jane Unsworth for a 40th; and a boy band reunion cruise to the Bahamas for a 45th in American Fantasy by Emma Straub.

- A reference to Sartre’s “hell is other people” line (paraphrased) in Two Women Living Together by Kim Hana and Hwang Sunwoo and The End of Mr Y by Scarlett Thomas.

- The clock-drawing test as a shorthand for assessing a loved one’s dementia in Book of Lives by Margaret Atwood (her partner Graeme) and Joyride by Susan Orlean (her mother).

A sexual encounter between two men is presaged by them relieving themselves side by side at urinals in A Room Above a Shop by Anthony Shapland and The End of Mr Y by Scarlett Thomas.

A sexual encounter between two men is presaged by them relieving themselves side by side at urinals in A Room Above a Shop by Anthony Shapland and The End of Mr Y by Scarlett Thomas.

- An older man who knows he’s having a stroke just wants to sit quietly in a chair and not be taken to hospital in Book of Lives by Margaret Atwood (her partner Graeme) and The Boy from the Sea by Garrett Carr.

- A man who’s gone through Alcoholics Anonymous gets dangerously close to falling off the wagon: picks up a bottle of gin in a shop in The Names by Florence Knapp / buys a drink at a bar in All the World Can Hold by Jung Yun.

- I was reading two nonfiction books with built-in red ribbon bookmarks at the same time: Book of Lives by Margaret Atwood and Robin by Stephen Moss.

- Homoeopathy is an element in The Names by Florence Knapp and The End of Mr Y by Scarlett Thomas.

- A character named Sparrow in Spent by Alison Bechdel and Songs of No Provenance by Lydi Conklin.

- A mention of special celebrations for a Korean mother’s 70 birthday in Two Women Living Together by Kim Hana and Hwang Sunwoo and All the World Can Hold by Jung Yun.

- Some kinky practices in Songs of No Provenance by Lydi Conklin and Mr Norris Changes Trains by Christopher Isherwood.

- A girl from an immigrant family reads Greek mythology for escape in Visitations by Julia Alvarez and The Mercy Step by Marcia Hutchinson.

- “View halloo” (originally a fox-hunting term) is used as a greeting in Talking It Over by Julian Barnes and Arsenic for Tea by Robin Stevens.

What’s the weirdest reading coincidence you’ve had lately?

Best Books of 2025

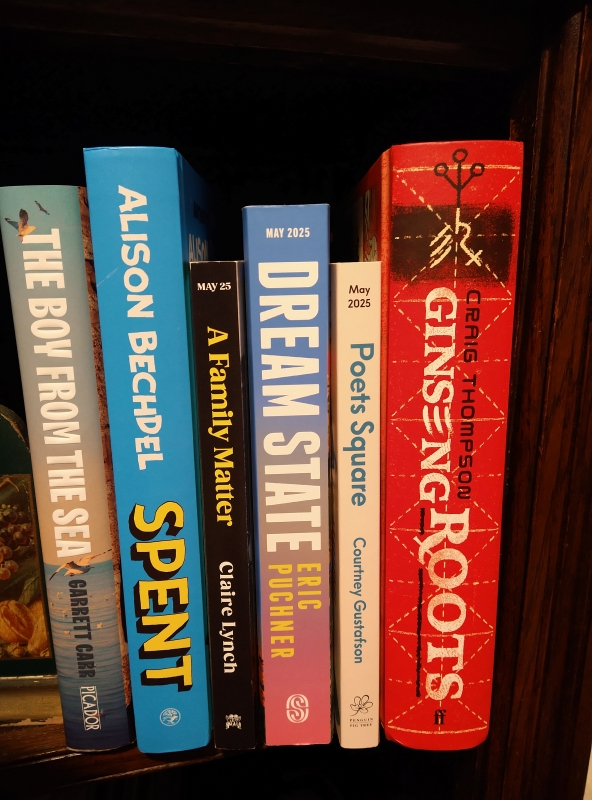

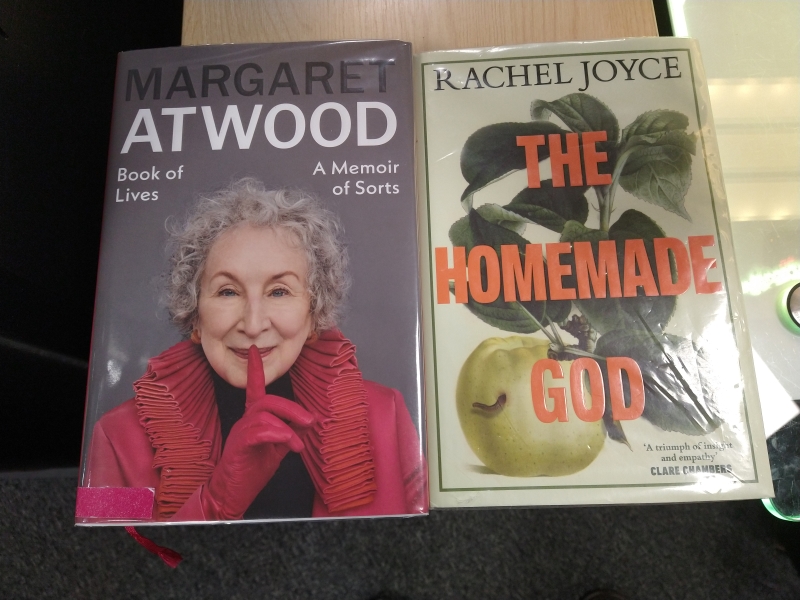

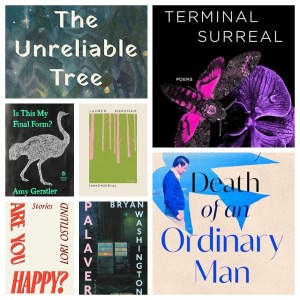

Without further ado, I present my 15 favourite releases from 2025. (With the 15 runners-up I chose yesterday, these represent about the top 9.5% of my current-year reading.) Pictured below are the ones I read in print; all the others were e-copies or library books I couldn’t get my hands on for a photo shoot. Links are to my full reviews where available.

Fiction

Spent: A Comic Novel by Alison Bechdel: Alison has writer’s block and is consumed with anxiety about the state of the world. “Who can draw when the world is burning?” Then she has an idea for a book – or a reality TV series – called $UM to wean people off of capitalism. That creative journey is mirrored here. Through Alison’s ageing hippie friends and their kids, Bechdel showcases alternative ways of living. Even the throwaway phrases are hilarious. It’s a gleeful and zeitgeist-y satire, yet draws to a touching close. So great, I read it twice.

Spent: A Comic Novel by Alison Bechdel: Alison has writer’s block and is consumed with anxiety about the state of the world. “Who can draw when the world is burning?” Then she has an idea for a book – or a reality TV series – called $UM to wean people off of capitalism. That creative journey is mirrored here. Through Alison’s ageing hippie friends and their kids, Bechdel showcases alternative ways of living. Even the throwaway phrases are hilarious. It’s a gleeful and zeitgeist-y satire, yet draws to a touching close. So great, I read it twice.

The Boy from the Sea by Garrett Carr: I was entranced by this story of an Irish family in the 1970s–80s: Ambrose, a fisherman left behind by technology; his wife Christine, walked all over by her belligerent father and sister; their son Declan, a budding foodie; and the title character, Brendan, a foundling they adopt and raise. Narrated by a chorus of village voices, this debut has the heart of Claire Keegan and the humour of Paul Murray. It reimagines biblical narratives, too: Cain and Abel, Jacob and Esau (brotherly rivalry!); Job and more.

The Boy from the Sea by Garrett Carr: I was entranced by this story of an Irish family in the 1970s–80s: Ambrose, a fisherman left behind by technology; his wife Christine, walked all over by her belligerent father and sister; their son Declan, a budding foodie; and the title character, Brendan, a foundling they adopt and raise. Narrated by a chorus of village voices, this debut has the heart of Claire Keegan and the humour of Paul Murray. It reimagines biblical narratives, too: Cain and Abel, Jacob and Esau (brotherly rivalry!); Job and more.

The Homemade God by Rachel Joyce: The story of four siblings initially drawn together (in Italy) and then dramatically blown apart by their father’s remarriage and death. Despite weighty themes including alcoholism and depression, there is an overall lightness of tone and style that made this a pleasure to read. Joyce has really upped her game: it’s more expansive, elegant and empathetic than her previous seven books. You can tell she got her start in theatre, too: she’s so good at scenes, dialogue, and moving groups of people around.

The Homemade God by Rachel Joyce: The story of four siblings initially drawn together (in Italy) and then dramatically blown apart by their father’s remarriage and death. Despite weighty themes including alcoholism and depression, there is an overall lightness of tone and style that made this a pleasure to read. Joyce has really upped her game: it’s more expansive, elegant and empathetic than her previous seven books. You can tell she got her start in theatre, too: she’s so good at scenes, dialogue, and moving groups of people around.

A Family Matter by Claire Lynch: In her research into UK divorce cases in the 1980s, Lynch learned that 90% of lesbian mothers lost custody of their children. Her earnest, delicate debut novel, which bounces between 2022 and 1982, imagines such a situation through close portraits of three family members. Maggie knew only that her mother, Dawn, abandoned her when she was little. Lynch’s compassion is equal for all three characters. This confident, tender story of changing mores and steadfast love is the new Carol for our times.

A Family Matter by Claire Lynch: In her research into UK divorce cases in the 1980s, Lynch learned that 90% of lesbian mothers lost custody of their children. Her earnest, delicate debut novel, which bounces between 2022 and 1982, imagines such a situation through close portraits of three family members. Maggie knew only that her mother, Dawn, abandoned her when she was little. Lynch’s compassion is equal for all three characters. This confident, tender story of changing mores and steadfast love is the new Carol for our times.

Are You Happy? by Lori Ostlund: Nine short fictions form a stunning investigation into how violence and family dysfunction reverberate. “The Peeping Toms” and “The Stalker” are a knockout pair featuring Albuquerque lesbian couples under threat by male acquaintances. Characters are haunted by loss and grapple with moral dilemmas. Each story has the complexity and emotional depth of a novel. Freedom versus safety for queer people is a resonant theme in an engrossing collection ideal for Alice Munro and Edward St. Aubyn fans.

Are You Happy? by Lori Ostlund: Nine short fictions form a stunning investigation into how violence and family dysfunction reverberate. “The Peeping Toms” and “The Stalker” are a knockout pair featuring Albuquerque lesbian couples under threat by male acquaintances. Characters are haunted by loss and grapple with moral dilemmas. Each story has the complexity and emotional depth of a novel. Freedom versus safety for queer people is a resonant theme in an engrossing collection ideal for Alice Munro and Edward St. Aubyn fans.

Dream State by Eric Puchner: It starts as a glistening romantic comedy about t Charlie and Cece’s chaotic wedding at a Montana lake house in summer 2004. First half the wedding party falls ill with norovirus, then the best man, Garrett, falls in love with the bride. The rest examines the fallout of this uneasy love triangle as it stretches towards 2050 and imagines a Western USA smothered in smoke from near-constant forest fires. Still, there are funny set-pieces and warm family interactions. Jonathan Franzen meets Maggie Shipstead.

Dream State by Eric Puchner: It starts as a glistening romantic comedy about t Charlie and Cece’s chaotic wedding at a Montana lake house in summer 2004. First half the wedding party falls ill with norovirus, then the best man, Garrett, falls in love with the bride. The rest examines the fallout of this uneasy love triangle as it stretches towards 2050 and imagines a Western USA smothered in smoke from near-constant forest fires. Still, there are funny set-pieces and warm family interactions. Jonathan Franzen meets Maggie Shipstead.

Palaver by Bryan Washington: Washington’s emotionally complex third novel explores the strained bond between a mother and her queer son – and their support systems of friends and lovers – when she visits him in Tokyo. The low-key plot builds through memories and interactions: the son’s with his students or hook-ups; the mother’s with restaurateurs as she gains confidence exploring Japan. Through words and black-and-white photographs, the author brings settings to life vibrantly. This is his best and most moving work yet.

Palaver by Bryan Washington: Washington’s emotionally complex third novel explores the strained bond between a mother and her queer son – and their support systems of friends and lovers – when she visits him in Tokyo. The low-key plot builds through memories and interactions: the son’s with his students or hook-ups; the mother’s with restaurateurs as she gains confidence exploring Japan. Through words and black-and-white photographs, the author brings settings to life vibrantly. This is his best and most moving work yet.

Nonfiction

Book of Lives: A Memoir of Sorts by Margaret Atwood: For diehard fans, this companion to her oeuvre is a trove of stories and photographs. The context on each book is illuminating and made me want to reread lots of her work. I was reminded how often she’s been ahead of her time. The title feels literal in that Atwood has been wilderness kid, literary ingénue, family and career woman, philanthropist and elder stateswoman. She doesn’t try to pull all her incarnations into one, instead leaving the threads trailing into the beyond.

Book of Lives: A Memoir of Sorts by Margaret Atwood: For diehard fans, this companion to her oeuvre is a trove of stories and photographs. The context on each book is illuminating and made me want to reread lots of her work. I was reminded how often she’s been ahead of her time. The title feels literal in that Atwood has been wilderness kid, literary ingénue, family and career woman, philanthropist and elder stateswoman. She doesn’t try to pull all her incarnations into one, instead leaving the threads trailing into the beyond.

Poets Square: A Memoir in 30 Cats by Courtney Gustafson: Working for a food bank, trapped in a cycle of dead-end jobs and rising rents: Gustafson saw first hand how broken systems and poverty wear people down. She’d recently started feeding and getting veterinary care for a feral cat colony in her Tucson, Arizona neighbourhood. With its radiant portraits of individual cats and its realistic perspective on personal and collective problems, this is a cathartic memoir and a probing study of building communities of care in times of hardship.

Poets Square: A Memoir in 30 Cats by Courtney Gustafson: Working for a food bank, trapped in a cycle of dead-end jobs and rising rents: Gustafson saw first hand how broken systems and poverty wear people down. She’d recently started feeding and getting veterinary care for a feral cat colony in her Tucson, Arizona neighbourhood. With its radiant portraits of individual cats and its realistic perspective on personal and collective problems, this is a cathartic memoir and a probing study of building communities of care in times of hardship.

Immemorial by Lauren Markham: An outstanding book-length essay that compares language, memorials, and rituals as strategies for coping with climate anxiety and grief. The dichotomies of the physical versus the abstract and the permanent versus the ephemeral are explored. Forthright, wistful, and determined, the book treats grief as a positive, as “fuel” or a “portal.” Hope is not theoretical in this setup, but solidified in action. This is an elegant meditation on memory and impermanence in an age of climate crisis.

Immemorial by Lauren Markham: An outstanding book-length essay that compares language, memorials, and rituals as strategies for coping with climate anxiety and grief. The dichotomies of the physical versus the abstract and the permanent versus the ephemeral are explored. Forthright, wistful, and determined, the book treats grief as a positive, as “fuel” or a “portal.” Hope is not theoretical in this setup, but solidified in action. This is an elegant meditation on memory and impermanence in an age of climate crisis.

Death of an Ordinary Man by Sarah Perry: Perry recognises what a sacred privilege it was to witness her father-in-law’s death nine days after his diagnosis with oesophageal cancer. David’s end was as peaceful as could be hoped: in his late seventies, at home and looked after by his son and daughter-in-law, with mental capacity and minimal pain or distress. The beauty of this direct but tender memoir is its patient, clear-eyed unfolding of every stage of dying, a natural and inexorable process that in other centuries would have been familiar to all.

Death of an Ordinary Man by Sarah Perry: Perry recognises what a sacred privilege it was to witness her father-in-law’s death nine days after his diagnosis with oesophageal cancer. David’s end was as peaceful as could be hoped: in his late seventies, at home and looked after by his son and daughter-in-law, with mental capacity and minimal pain or distress. The beauty of this direct but tender memoir is its patient, clear-eyed unfolding of every stage of dying, a natural and inexorable process that in other centuries would have been familiar to all.

Ginseng Roots by Craig Thompson: A book about everything, by way of ginseng. It begins with Thompson’s childhood summers working on American ginseng farms with his siblings in Marathon, Wisconsin. As an adult, he travels first to Midwest ginseng farms and festivals and then through China and Korea to learn about the plant’s history, cultivation, lore, and medicinal uses. Roots are symbolic of a family story that unfolds in parallel. Both expansive and intimate, this is a surprising gem from one of the best long-form graphic storytellers.

Ginseng Roots by Craig Thompson: A book about everything, by way of ginseng. It begins with Thompson’s childhood summers working on American ginseng farms with his siblings in Marathon, Wisconsin. As an adult, he travels first to Midwest ginseng farms and festivals and then through China and Korea to learn about the plant’s history, cultivation, lore, and medicinal uses. Roots are symbolic of a family story that unfolds in parallel. Both expansive and intimate, this is a surprising gem from one of the best long-form graphic storytellers.

Poetry

Is This My Final Form? by Amy Gerstler: This delightfully odd collection amazes with its range of voices and techniques. It leaps from surrealism to elegy as it ponders life’s randomness. The language of transformation is integrated throughout. Aging and the seasons are examples of everyday changes. Elsewhere, speakers fall in love with the bride of Frankenstein or turn to dinosaur urine for a wellness regimen. Monologues and sonnets recur. Alliteration plus internal and end rhymes create satisfying resonance.

Is This My Final Form? by Amy Gerstler: This delightfully odd collection amazes with its range of voices and techniques. It leaps from surrealism to elegy as it ponders life’s randomness. The language of transformation is integrated throughout. Aging and the seasons are examples of everyday changes. Elsewhere, speakers fall in love with the bride of Frankenstein or turn to dinosaur urine for a wellness regimen. Monologues and sonnets recur. Alliteration plus internal and end rhymes create satisfying resonance.

The Unreliable Tree by Margot Kahn: Kahn’s radiant first collection ponders how traumatic events interrupt everyday life. Poles of loss and abundance structure delicate poems infused with family history and food imagery. The title phrase describes literal harvests but is also a metaphor for the vicissitudes of long relationships. California’s wildfires, Covid-19, a mass shooting, and health crises – an emergency surgery and a friend’s cancer – serve as reminders of life’s unpredictability. Disaster is random and inescapable.

The Unreliable Tree by Margot Kahn: Kahn’s radiant first collection ponders how traumatic events interrupt everyday life. Poles of loss and abundance structure delicate poems infused with family history and food imagery. The title phrase describes literal harvests but is also a metaphor for the vicissitudes of long relationships. California’s wildfires, Covid-19, a mass shooting, and health crises – an emergency surgery and a friend’s cancer – serve as reminders of life’s unpredictability. Disaster is random and inescapable.

Terminal Surreal by Martha Silano: Silano’s posthumous collection (her eighth) focuses on nature and relationships as she commemorates the joys and ironies of her last years with ALS. The shock of a terminal diagnosis was eased by the quotidian pleasures of observing Pacific Northwest nature, especially birds. Fascination with science recurs, too. Most pieces are free form and alliteration and wordplay enliven the register. Her winsome philosophical work is a gift. “What doesn’t die? / The closest I’ve come to an answer / is poetry.”

Terminal Surreal by Martha Silano: Silano’s posthumous collection (her eighth) focuses on nature and relationships as she commemorates the joys and ironies of her last years with ALS. The shock of a terminal diagnosis was eased by the quotidian pleasures of observing Pacific Northwest nature, especially birds. Fascination with science recurs, too. Most pieces are free form and alliteration and wordplay enliven the register. Her winsome philosophical work is a gift. “What doesn’t die? / The closest I’ve come to an answer / is poetry.”

If I had to pick one from each genre? Well, like last year, I find that the books that have stuck with me most are the ones that play around with the telling of life stories. This time, all by women. So it’s Spent, Book of Lives and Is This My Final Form?

What 2025 releases should I catch up on?