Sister Outsider by Audre Lorde (#NovNov25 Buddy Read, #NonfictionNovember)

This year we set two buddy reads for Novellas in November: one contemporary work of fiction (Seascraper) and one classic work of short nonfiction. Do let us know if you’ve been reading them and what you think!

Sister Outsider is a 1984 collection of Audre Lorde’s essays and speeches. Many of these short pieces appeared in Black or radical feminist magazines or scholarly journals, while a few give the text of her conference presentations. Lorde must have been one of the first writers to spotlight intersectionality: she ponders the combined effect of her Black lesbian identity on how she is perceived and what power she has in society.

The title’s paradox draws attention to the push and pull of solidarity and ostracism. She calls white feminists out for not considering what women of colour endure (or for making her a token Black speaker); she decries misogyny in the Black community; and she and her white lover, Frances, seem to attract homophobia from all quarters. Especially while trying to raise her Black teenage son to avoid toxic masculinity, the author comes to realise the importance of “learning to address each other’s difference with respect.”

This is a point she returns to again and again, and it’s as important now as it was when she was writing in the 1970s. So many forms of hatred and discrimination come down to difference being seen as a threat – “I disagree with you, so I must destroy you” is how she caricatures that perspective.

Even if you’ve never read a word that Lorde wrote, you probably know the phrase “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House” – this talk title refers to having to circumvent the racist patriarchy to truly fight oppression. “Revolution is not a one-time event,” she writes in another essay. “It is becoming always vigilant for the smallest opportunity to make a genuine change in established, outgrown responses”.

Even if you’ve never read a word that Lorde wrote, you probably know the phrase “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House” – this talk title refers to having to circumvent the racist patriarchy to truly fight oppression. “Revolution is not a one-time event,” she writes in another essay. “It is becoming always vigilant for the smallest opportunity to make a genuine change in established, outgrown responses”.

My two favourite pieces here also feel like they have entered into the zeitgeist. “Poetry Is Not a Luxury” deems poetry a “necessity for our existence … the way we help give name to the nameless so it can be thought.” And “Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power” is a thrilling redefinition of a holistic sensuality that means living at full tilt and tapping into creativity. “The sharing of joy, whether physical, emotional, psychic, or intellectual, forms a bridge between the sharers which can be the basis for understanding much of what is not shared”.

In some ways this is not an ideal way to be introduced to Lorde’s work, because many of the essays repeat the same themes and reasoning. I made my way through the book very slowly, one piece every day or few days. The speeches would almost certainly be more effective if heard aloud, as intended – and more provocative, too, as they must have undermined other speakers’ assumptions. I was also a bit taken aback by the opening and closing pieces being travelogues: “Notes from a Trip to Russia” is based on journal entries from 1976, while “Grenada Revisited: An Interim Report” about a 1983 trip to her mother’s birthplace. I saw more point to the latter, while the former felt somewhat out of place.

Nonetheless, Lorde’s thinking is essential and ahead of its time. I’d only previously read her short work The Cancer Journals. For years my book club has been toying with reading Zami, her memoir starting with growing up in 1930s Harlem, so I’ll hope to move that up the agenda for next year. Have you read any of her other books that you can recommend?(University library) [190 pages]

Other reviews of Sister Outsider:

Cathy (746 Books)

Marcie (Buried in Print) is making her way through the book one essay at a time. Here’s her latest post.

Reading Ireland Month: Seán Hewitt, Maggie O’Farrell

Reading Ireland Month is hosted each year by Cathy of 746 Books. I’m wishing you all well on St. Patrick’s Day with this first of two planned tie-in posts. Today I have a poetry collection that sets grief and queer longing amid nature, and my last unread novel – a somewhat middling one, unfortunately – by one of my favourite authors.

Rapture’s Road by Seán Hewitt (2024)

The points of reference are so similar to his 2020 debut collection, Tongues of Fire, that parts of what I wrote about that one are fully applicable here: “Sex and grief, two major themes, are silhouetted against the backdrop of nature. Fields and forests are loci of meditation and epiphany, but also of clandestine encounters between men.” Perhaps inevitably, then, this felt less fresh, but there was still much to enjoy. I particularly loved two poems about moths (the merveille du jour as an “art-deco mint-green herringbone. Soft furred little absinthe warrior”), “To Autumn,” and “Alcyone,” which likens a kingfisher to “a rip / in the year’s old fabric”.

The points of reference are so similar to his 2020 debut collection, Tongues of Fire, that parts of what I wrote about that one are fully applicable here: “Sex and grief, two major themes, are silhouetted against the backdrop of nature. Fields and forests are loci of meditation and epiphany, but also of clandestine encounters between men.” Perhaps inevitably, then, this felt less fresh, but there was still much to enjoy. I particularly loved two poems about moths (the merveille du jour as an “art-deco mint-green herringbone. Soft furred little absinthe warrior”), “To Autumn,” and “Alcyone,” which likens a kingfisher to “a rip / in the year’s old fabric”.

In “Two Apparitions,” the poet’s late father seems visible again. Many of the scenes take place at dusk or dark. There’s a layer of menace to “Night-Scented Stock,” about an abusive relationship, and the account of a slaughter in “Pig.” But the stand-out is “We Didn’t Mean to Kill Mr Flynn,” based on the 1982 murder of a gay man in a Dublin park. Hewitt drew lines from court proceedings and periodicals in the Irish Queer Archive at the National Library of Ireland, where he was poet in residence. He voices first the gang of killers, then Flynn himself. The trial kickstarted Ireland’s Pride movement.

More favourite lines:

Come out, make a verb of me, let

my body do your speaking tonight —

(from “A Strain of the Earth’s Sweet Being”)

awestruck, bright,

a child in the bell-tower of beauty —

(from “Skylarks”)

Love, the world is failing:

come and fail with me.

(from “Nightfall”)

With thanks to Jonathan Cape (Penguin) for the free copy for review.

My Lover’s Lover by Maggie O’Farrell (2002)

I was so excited, a few years ago, to find battered copies of this and After You’d Gone in a local charity shop for 50 pence each, even though it appears a mouse had a nibble on one corner here. They were her first two books, but the last that I managed to source. Whereas After You’d Gone is a surprisingly confident and elegant debut novel about a woman in a coma and the family and romantic relationships that brought her to this point, My Lover’s Lover ultimately felt like a pretty run-of-the-mill story about two women finding out that (some) men are dogs and they need to break free.

Lily meets Marcus, an architect, at a party and almost before she knows it has moved into the spare room of his apartment, a Victorian factory space he renovated himself, and become his lover. But there’s an uncomfortable atmosphere in the flat: She can still smell perfume from Marcus’s ex, Sinead; one of her dresses hangs in the closet. We, along with Lily, get the impression Sinead has died. She haunts not just the flat but also the streets of London. It becomes Lily’s obsession to find out what happened to Sinead and why Marcus is so morose. Part Two gives Sinead’s side of things, in a mix of third person/present tense and first person/past tense, before we return to Lily to see what she’ll do with her new knowledge.

Lily meets Marcus, an architect, at a party and almost before she knows it has moved into the spare room of his apartment, a Victorian factory space he renovated himself, and become his lover. But there’s an uncomfortable atmosphere in the flat: She can still smell perfume from Marcus’s ex, Sinead; one of her dresses hangs in the closet. We, along with Lily, get the impression Sinead has died. She haunts not just the flat but also the streets of London. It becomes Lily’s obsession to find out what happened to Sinead and why Marcus is so morose. Part Two gives Sinead’s side of things, in a mix of third person/present tense and first person/past tense, before we return to Lily to see what she’ll do with her new knowledge.

As in some later novels, there are multiple locales (here, NYC, the Australian desert, and China – a country O’Farrell often revisits in fiction) and complicated point-of-view shifts, but I felt the sophisticated craft was rather wasted on a book that boils down to a self-explanatory maxim: past relationships always have an effect on current ones. I also found the writing overmuch in places (“the grass swooshing, sussurating, cleaving open to her steps”; “letting fall a box of cereal into its [a shopping trolley’s] chrome meshing”; “her fingertips meeting the ceraceous, heated skin of his cheek”). However, this was an engrossing read – I read most of it in two days. It’s bottom-tier O’Farrell, though, along with The Distance Between Us and Hamnet – sorry, I know many adore it. (If you’re interested: middle tier = The Vanishing Act of Esme Lennox, Instructions for a Heatwave, her two children’s books, and The Marriage Portrait; top tier = After You’d Gone, The Hand that First Held Mine, This Must Be the Place, and I Am, I Am, I Am.)

I’ve gotten in the habit of reading one of Maggie O’Farrell’s works per year, so I will just have to reread my favourites until we get a new one. I’m already tapping a foot in impatience. (Secondhand from Bas, Newbury)

Have you read any Irish literature this month?

This is the middle of a trio of stories about Maya. They’re not in a row and I read the book over quite a number of months, so I was in danger of forgetting that we’d met this set of characters before. In the first, the title story, Maya has been with Rhodes for five years but is thinking of leaving him – and not just because she’s crushing on her boss. A health crisis with her dog leads her to rethink. In “Grendel’s Mother,” Maya is pregnant and hoping that she and her partner are on the same page.

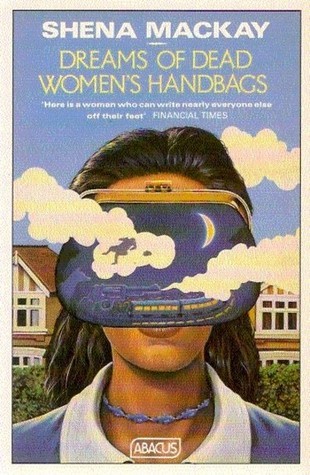

This is the middle of a trio of stories about Maya. They’re not in a row and I read the book over quite a number of months, so I was in danger of forgetting that we’d met this set of characters before. In the first, the title story, Maya has been with Rhodes for five years but is thinking of leaving him – and not just because she’s crushing on her boss. A health crisis with her dog leads her to rethink. In “Grendel’s Mother,” Maya is pregnant and hoping that she and her partner are on the same page. I’ve had a mixed experience with Mackay, but the one novel of hers I got on well with, The Orchard on Fire, also dwells on the shattered innocence of childhood. By contrast, most of the stories in this collection are grimy ones about lonely older people – especially elderly women – reminding me of Barbara Comyns or Barbara Pym at her darkest. “Where the Carpet Ends,” about the long-term residents of a shabby hotel, recalls

I’ve had a mixed experience with Mackay, but the one novel of hers I got on well with, The Orchard on Fire, also dwells on the shattered innocence of childhood. By contrast, most of the stories in this collection are grimy ones about lonely older people – especially elderly women – reminding me of Barbara Comyns or Barbara Pym at her darkest. “Where the Carpet Ends,” about the long-term residents of a shabby hotel, recalls  Of course, I also loved “The Cat,” which Eleanor mentioned when she read my review of Matt Haig’s

Of course, I also loved “The Cat,” which Eleanor mentioned when she read my review of Matt Haig’s

Asher and Ivan, two characters of nebulous sexuality and future gender, are the core of “Cheerful Until Next Time” (check out the acronym), which has the fantastic opening line “The queer feminist book club came to an end.” “Laramie Time” stars a lesbian couple debating whether to have a baby (in the comic Leigh draws, a turtle wishes “reproduction was automatic or mandatory, so no decision was necessary”). “A Fearless Moral Inventory” features a pansexual who is a recovering sex addict. Adolescent girls are the focus in “The Black Winter of New England” and “Ooh, the Suburbs,” where they experiment with making lesbian leanings public and seeking older role models. “Pioneer,” probably my second favorite, has Coco pushing against gender constraints at a school Oregon Trail reenactment. Refusing to be a matriarch and not allowed to play a boy, she rebels by dressing up as an ox instead. The tone is often bleak or yearning, so “Counselor of My Heart” stands out as comic even though it opens with the death of a dog; Molly’s haplessness somehow feels excusable.

Asher and Ivan, two characters of nebulous sexuality and future gender, are the core of “Cheerful Until Next Time” (check out the acronym), which has the fantastic opening line “The queer feminist book club came to an end.” “Laramie Time” stars a lesbian couple debating whether to have a baby (in the comic Leigh draws, a turtle wishes “reproduction was automatic or mandatory, so no decision was necessary”). “A Fearless Moral Inventory” features a pansexual who is a recovering sex addict. Adolescent girls are the focus in “The Black Winter of New England” and “Ooh, the Suburbs,” where they experiment with making lesbian leanings public and seeking older role models. “Pioneer,” probably my second favorite, has Coco pushing against gender constraints at a school Oregon Trail reenactment. Refusing to be a matriarch and not allowed to play a boy, she rebels by dressing up as an ox instead. The tone is often bleak or yearning, so “Counselor of My Heart” stands out as comic even though it opens with the death of a dog; Molly’s haplessness somehow feels excusable.

Laskey inhabits all 11 personae with equal skill and compassion. Avery, the task force leader’s daughter, resents having to leave L.A. and plots an escape with her new friend Zach, a persecuted gay teen. Christine, a Christian homemaker, is outraged about the liberal agenda, whereas her bereaved neighbor, Linda, finds purpose and understanding in volunteering at the AAA office. Food hygiene inspector Henry is thrown when his wife leaves him for a woman, and meat-packing maven Lizzie agonizes over the question of motherhood. Task force members David, Tegan and Harley all have their reasons for agreeing to the project, but some characters have to sacrifice more than others.

Laskey inhabits all 11 personae with equal skill and compassion. Avery, the task force leader’s daughter, resents having to leave L.A. and plots an escape with her new friend Zach, a persecuted gay teen. Christine, a Christian homemaker, is outraged about the liberal agenda, whereas her bereaved neighbor, Linda, finds purpose and understanding in volunteering at the AAA office. Food hygiene inspector Henry is thrown when his wife leaves him for a woman, and meat-packing maven Lizzie agonizes over the question of motherhood. Task force members David, Tegan and Harley all have their reasons for agreeing to the project, but some characters have to sacrifice more than others.

Four of the nine are holiday-themed, so this could make a good Twixtmas read if you like seasonality; eight are in the third person and just one has alternating first person narrators. All are what could be broadly dubbed romances, with most involving meet-cutes or moments when long-time friends realize their feelings go deeper (“Midnights” and “The Snow Ball”). Only one of the pairings is queer, however: Baz and Simon (who are a vampire and … a dragon-man, I think? and the subjects of a trilogy) in the Harry Potter-meets Twilight-meets Heartstopper “Snow for Christmas.” The rest are pretty straightforward boy-girl stories.

Four of the nine are holiday-themed, so this could make a good Twixtmas read if you like seasonality; eight are in the third person and just one has alternating first person narrators. All are what could be broadly dubbed romances, with most involving meet-cutes or moments when long-time friends realize their feelings go deeper (“Midnights” and “The Snow Ball”). Only one of the pairings is queer, however: Baz and Simon (who are a vampire and … a dragon-man, I think? and the subjects of a trilogy) in the Harry Potter-meets Twilight-meets Heartstopper “Snow for Christmas.” The rest are pretty straightforward boy-girl stories.