April 3rd Releases by Emily Jungmin Yoon & Jean Hannah Edelstein

It’s not often that I manage to review books for their publication date rather than at the end of the month, but these two were so short and readable that I polished them off over the first few days of April. So, out today in the UK: a poetry collection about Asian American identity and environmental threat, and a memoir in miniature about how body parts once sexualized and then functionalized are missed once they’re gone.

Find Me as the Creature I Am by Emily Jungmin Yoon (2024)

The Korean American poet’s second full-length work is broadly about loss experienced or expected – but also about the love that keeps us going in dire times. The free verse links personal bereavement with larger-scale tragedies, including climate grief. “All my friends who loved trees are dead” tells of Yoon’s grandmother’s death, while “I leave Asia and become Asian” remembers the murders of eight Asian spa workers in Atlanta in 2021. Violence against women, and the way the Covid-19 pandemic spurred further anti-Asian racism, are additional topics in the early part of the book. For me, Part III’s environmental poems resonated the most. Yoon reflects on the ways in which we are, sometimes unwittingly, affecting the natural world, especially marine ecosystems: “there is no ‘eco-friendly’ way to swim with dolphins. / We do not have to touch everything we love,” she writes. “I look at the ocean like it’s goodbye. … I look at your face / like it’s goodbye.” This is a tricky one to assess; while I appreciated the themes, I did not find the style or language distinctive. The collection reminded me of a cross between Rupi Kaur and Jenny Xie.

The Korean American poet’s second full-length work is broadly about loss experienced or expected – but also about the love that keeps us going in dire times. The free verse links personal bereavement with larger-scale tragedies, including climate grief. “All my friends who loved trees are dead” tells of Yoon’s grandmother’s death, while “I leave Asia and become Asian” remembers the murders of eight Asian spa workers in Atlanta in 2021. Violence against women, and the way the Covid-19 pandemic spurred further anti-Asian racism, are additional topics in the early part of the book. For me, Part III’s environmental poems resonated the most. Yoon reflects on the ways in which we are, sometimes unwittingly, affecting the natural world, especially marine ecosystems: “there is no ‘eco-friendly’ way to swim with dolphins. / We do not have to touch everything we love,” she writes. “I look at the ocean like it’s goodbye. … I look at your face / like it’s goodbye.” This is a tricky one to assess; while I appreciated the themes, I did not find the style or language distinctive. The collection reminded me of a cross between Rupi Kaur and Jenny Xie.

Published in the USA by Knopf on October 22, 2024. With thanks to Atlantic Books for the free copy for review.

Breasts: A Relatively Brief Relationship by Jean Hannah Edelstein

From my Most Anticipated list. I loved Edelstein’s 2018 memoir This Really Isn’t About You, and I regularly read her Substack. This micro-memoir in three essays explores the different roles breasts have played in her life: “Sex” runs from the day she went shopping for her first bra as a teenager with her mother through to her early thirties living in London. Edelstein developed early and eventually wore size DD, which attracted much unwanted attention in social situations and workplaces alike. (And not just a slightly sleazy bar she worked in, but an office, too. Twice she was groped by colleagues; the second time she reported it. But: drunk, Christmas party, no witnesses; no consequences.) “It felt like a punishment, a consequence of my own behavior (being a woman, having a fun night out, doing these things while having large breasts),” she writes.

“Food” recounts how her perspective on her breasts changed when she had her two children via IVF – so they wouldn’t inherit Lynch syndrome from her – and initially struggled to breastfeed. “I wanted to experience the full utility of my breasts,” she explains, so, living in Brooklyn now, she consulted a lactation consultant known as “the breast whisperer.” Part 3 is “Cancer”: when Edelstein was 41, mammograms discovered Stage 0 cancer in one breast. “For so long I’d been subject to unwelcome opinions about the kind of person that I was because of the size of my breasts.” But now it was up to her. She chose a double mastectomy for balance, with simultaneous reconstruction by a plastic surgeon.

“Food” recounts how her perspective on her breasts changed when she had her two children via IVF – so they wouldn’t inherit Lynch syndrome from her – and initially struggled to breastfeed. “I wanted to experience the full utility of my breasts,” she explains, so, living in Brooklyn now, she consulted a lactation consultant known as “the breast whisperer.” Part 3 is “Cancer”: when Edelstein was 41, mammograms discovered Stage 0 cancer in one breast. “For so long I’d been subject to unwelcome opinions about the kind of person that I was because of the size of my breasts.” But now it was up to her. She chose a double mastectomy for balance, with simultaneous reconstruction by a plastic surgeon.

Although this is a likable book, the retelling is quite flat; better that than mawkish, certainly, but none of the experiences feel particularly unique. It’s more a generic rundown of what it’s like to be female – which, yes, varies to an extent but not that much if we’re talking about the male gaze. There wasn’t the same spark or wit that I found in Edelstein’s first book. Perhaps in the context of a longer memoir, I would have appreciated these essays more.

With thanks to Phoenix for the free copy for review.

Nonfiction November: Two Memoirs of Biblical Living by Evans and Jacobs

I love a good year-challenge narrative and couldn’t resist considering these together because of the shared theme. Sure, there’s something gimmicky about a rigorously documented attempt to obey the Bible’s literal commandments as closely as possible in the modern day. But these memoirs arise from sincere motives, take cultural and theological matters seriously, and are a lot of fun to read.

The Year of Living Biblically: One Man’s Humble Quest to Follow the Bible as Literally as Possible by A.J. Jacobs (2007)

Jacobs came up with the idea, so I’ll start with him. His first book, The Know-It-All, was about absorbing as much knowledge as possible by reading the encyclopaedia. This starts in similarly intellectual fashion with a giant stack of Bible translations and commentaries. From one September to the next, Jacobs vows, he’ll do his best to understand and implement commandments from both the Old and New Testaments. It’s not a completely random choice of project in that he’s a secular Jew (“I’m Jewish in the same way the Olive Garden is an Italian restaurant. Which is to say: not very.”). Firstly, and most obviously, he stops shaving and getting haircuts. “As I write this, I have a beard that makes me resemble Moses. Or Abe Lincoln. Or [Unabomber] Ted Kaczynski. I’ve been called all three.” When he also takes to wearing all white, he really stands out on the New York subway system. Loving one’s neighbour isn’t easy in such an antisocial city, but he decides to try his best.

Jacobs is confused by the Bible’s combination of sensible moral guidelines and bizarre, arcane stuff. His conviction is that you can’t pick and choose – even if you don’t know why a law is important, you have to go with it. One of his “Top Five Most Perplexing Rules in the Bible” is a ban on clothing made of mixed fibers (shatnez). So he hires a shatnez tester, Mr. Berkowitz, who comes to investigate his entire wardrobe. To fulfil another obscure commandment, Berkowitz helps him ceremonially take an egg from a pigeon’s nest. Jacobs takes up prayer, hospitality, tithing, dietary restrictions, and avoiding women at the wrong time of the month. He gamely puts up a mezuzah, which displays a Bible passage above his doorframe. He even, I’m sorry to report, has a chicken sacrificed. Despite the proverb about not ‘sparing the rod’, he can’t truly bring himself to punish his son, so taps him gently with a Nerf bat; alas, Jasper thinks it’s a game. Stoning adulterers? Jacobs tosses pebbles at ankles.

Jacobs is confused by the Bible’s combination of sensible moral guidelines and bizarre, arcane stuff. His conviction is that you can’t pick and choose – even if you don’t know why a law is important, you have to go with it. One of his “Top Five Most Perplexing Rules in the Bible” is a ban on clothing made of mixed fibers (shatnez). So he hires a shatnez tester, Mr. Berkowitz, who comes to investigate his entire wardrobe. To fulfil another obscure commandment, Berkowitz helps him ceremonially take an egg from a pigeon’s nest. Jacobs takes up prayer, hospitality, tithing, dietary restrictions, and avoiding women at the wrong time of the month. He gamely puts up a mezuzah, which displays a Bible passage above his doorframe. He even, I’m sorry to report, has a chicken sacrificed. Despite the proverb about not ‘sparing the rod’, he can’t truly bring himself to punish his son, so taps him gently with a Nerf bat; alas, Jasper thinks it’s a game. Stoning adulterers? Jacobs tosses pebbles at ankles.

The book is a near-daily journal, with a new rule or three grappled with each day. There are hundreds of strange and culturally specific guidelines, but the heart issues – covetousness, lust – pose more of a challenge. Alongside his work as a journalist for Esquire and this project, Jacobs has family stuff going on: IVF results in his wife’s pregnancy with twin boys. Before they become a family of five, he manages to meet some Amish people, visit the Creation Museum, take a trip to the Holy Land to see a long-lost uncle, and engage in conversation with Evangelicals across the political spectrum, from Jerry Falwell’s megachurch to Tony Campolo (who died just last week). Jacobs ends up a “reverent agnostic.” We needn’t go to such extremes to develop the gratitude he feels by the end, but it sure is a hoot to watch him. This has just the sort of amusing, breezy yet substantial writing that should engage readers of Bill Bryson, Dave Gorman and Jon Ronson. (Free mall bookshop) ![]()

A Year of Biblical Womanhood: How a Liberated Woman Found Herself Sitting on Her Roof, Covering Her Head, and Calling Her Husband “Master” by Rachel Held Evans (2012)

Evans’s book proposal must have referenced Jacobs’s project, but she comes at things from a different perspective as a progressive Christian, and likely had a separate audience in mind. Namely, the sort of people who worry about the concept of biblical womanhood and wrestle with Bible verses about women remaining silent in church and not holding positions of religious leadership over men. There are indeed factions of Christianity that take these passages literally. Given that she was a public speaker and popular theologian, Evans obviously didn’t. But in her native Alabama and her new home of Tennessee, many would. She decides to look more closely at some of the prescriptions for women in the scriptures, focusing on Proverbs 31, which describes the “woman of valor.” She looks at this idealized woman’s characteristics in turn and tries to adhere to them by dressing modestly, taking etiquette lessons, learning to cook and hosting dinners, and practicing for parenthood with a “Baby-Think-It-Over” doll. Like Jacobs, she stops cutting her hair and meets some Amish people. But she also sleeps outside in a tent while menstruating and undertakes silent meditation at an abbey and a mission trip to Bolivia. Each monthly chapter ends with a profile of a female character from the Bible and what might be learned from her story.

Evans’s book proposal must have referenced Jacobs’s project, but she comes at things from a different perspective as a progressive Christian, and likely had a separate audience in mind. Namely, the sort of people who worry about the concept of biblical womanhood and wrestle with Bible verses about women remaining silent in church and not holding positions of religious leadership over men. There are indeed factions of Christianity that take these passages literally. Given that she was a public speaker and popular theologian, Evans obviously didn’t. But in her native Alabama and her new home of Tennessee, many would. She decides to look more closely at some of the prescriptions for women in the scriptures, focusing on Proverbs 31, which describes the “woman of valor.” She looks at this idealized woman’s characteristics in turn and tries to adhere to them by dressing modestly, taking etiquette lessons, learning to cook and hosting dinners, and practicing for parenthood with a “Baby-Think-It-Over” doll. Like Jacobs, she stops cutting her hair and meets some Amish people. But she also sleeps outside in a tent while menstruating and undertakes silent meditation at an abbey and a mission trip to Bolivia. Each monthly chapter ends with a profile of a female character from the Bible and what might be learned from her story.

It’s a sweet, self-deprecating book. You can definitely tell that she was only 29 at the time she started her project. It’s okay with me that Evans turned all her literal intentions into more metaphorical applications by the end of the year. She concludes that the Church has misused Proverbs 31: “We abandoned the meaning of the poem by focusing on the specifics, and it became just another impossible standard by which to measure our failures. We turned an anthem into an assignment, a poem into a job description.” Her determination is not to obsess over rules but to continue with the habits that benefited her spiritual life, and to champion women whenever she can. I suspect this is a lesser entry from Evans’s oeuvre. She died too soon – suddenly in 2019, of brain swelling after a severe allergic reaction to an antibiotic – but remains a valued voice, and I’ll catch up on the rest of her books. Searching for Sunday, for instance, was great, and I’m keen to read Evolving in Monkey Town (about living in Dayton, Tennessee, where the famous Scopes Monkey Trial took place). (Birthday gift from my wish list, 2023) ![]()

20 Books of Summer, 15–17: Bill Buford, Kristin Newman, J. Courtney Sullivan

One last foodie selection for the summer: a chef’s memoir set mostly in Lyon, France. Plus a bawdy travel memoir I DNFed halfway through, and an engaging but probably overlong contemporary novel about finances, generational conflict and women’s relationships.

Dirt: Adventures in French Cooking by Bill Buford (2020)

Buford’s Heat was one of the highlights of my foodie summer reading in 2020. This is a sequel insomuch as it tells you what he did next, after his Italian-themed apprenticeships. The short answer is that he went to Lyon to learn French cooking in similarly obsessive fashion. Without knowing a word of French. And this time he had a wife and twin toddlers in tow. He met several celebrated French chefs – Michel Richard, Paul Bocuse, Daniel Boulud – and talked his way into training at a famous cookery school and in Michelin-starred kitchens.

Buford’s Heat was one of the highlights of my foodie summer reading in 2020. This is a sequel insomuch as it tells you what he did next, after his Italian-themed apprenticeships. The short answer is that he went to Lyon to learn French cooking in similarly obsessive fashion. Without knowing a word of French. And this time he had a wife and twin toddlers in tow. He met several celebrated French chefs – Michel Richard, Paul Bocuse, Daniel Boulud – and talked his way into training at a famous cookery school and in Michelin-starred kitchens.

These experiences are discussed in separate essays, so I rather lost track of the timeline. It’s odd that it took the author so many years to get around to publishing about it all. You’d think his sons were still young, but in fact they’re now approaching adulthood. The other slightly unusual thing is the amount of space Buford devotes to his pet theory that French cuisine (up to ragout, at least) evolved from Italian. Unsurprisingly, the French don’t favour this idea; I didn’t particularly care one way or the other.

Nonetheless, I enjoyed reading about his encounters with French bureaucracy; the stress of working in busy (and macho) restaurants, where he’s eventually entrusted with cooking the staff lunch; and his discovery of what makes for good bread: small wheat-growing operations rather than industrially produced flour – his ideal was the 90-cent baguette from his local boulangerie. This could have been a bit more focused, and I’m still more likely to recommend Heat, but I am intrigued to go to Lyon one day. (Secondhand gift, Christmas 2022)

What I Was Doing While You Were Breeding by Kristin Newman (2014)

(DNF, 156/291 pages) As featured in my Six Degrees post earlier in the month. Newman is a comedy writer for film and television (That ’70s Show, How I Met Your Mother, etc.). I liked how the title unabashedly centres things other than couplehood and procreation. When she’s travelling, she can be spontaneous, open-to-experience “Kristin-adjacent,” who loves doing whatever it is that locals do. And be a party girl, of course (“If there is one thing that is my favorite thing in the world, it’s making out on a dance floor”). However, this chronological record of her sexual conquests in Amsterdam, Paris, Russia, Argentina, etc. gets repetitive and raunchy. I also felt let down when I learned that she married and had a child right after she published it. So this was just her “Pietra Pan” stage before she copied everyone else. Which is fine, but were her drunken shenanigans really worth commemorating? (Secondhand, Bas Books & Home)

(DNF, 156/291 pages) As featured in my Six Degrees post earlier in the month. Newman is a comedy writer for film and television (That ’70s Show, How I Met Your Mother, etc.). I liked how the title unabashedly centres things other than couplehood and procreation. When she’s travelling, she can be spontaneous, open-to-experience “Kristin-adjacent,” who loves doing whatever it is that locals do. And be a party girl, of course (“If there is one thing that is my favorite thing in the world, it’s making out on a dance floor”). However, this chronological record of her sexual conquests in Amsterdam, Paris, Russia, Argentina, etc. gets repetitive and raunchy. I also felt let down when I learned that she married and had a child right after she published it. So this was just her “Pietra Pan” stage before she copied everyone else. Which is fine, but were her drunken shenanigans really worth commemorating? (Secondhand, Bas Books & Home)

Friends and Strangers by J. Courtney Sullivan (2020)

I got Emma Straub vibes from this big, juicy novel focusing on two women in upstate New York: Elisabeth, a married journalist who moved out of Brooklyn when she finally conceived via IVF; and Sam, a college art student who becomes her son Gil’s babysitter. Elisabeth misses her old crowd and doesn’t fit in with the middle-aged book club ladies in her suburban neighbourhood; Sam is almost her only friend, a confidante who’s also like a little sister (better, anyway, than Elisabeth’s real sister, who lives on tropical islands and models swimwear for inspirational Instagram posts). And Sam admires Elisabeth for simultaneously managing a career and motherhood with seeming aplomb.

But fundamental differences between the two emerge, mostly to do with economics. Elisabeth comes from money and takes luxury products for granted, while Sam is solidly working-class and develops a surprising affinity with Elisabeth’s father-in-law, George, who is near bankruptcy after Uber killed off his car service business. His pet theory, “The Hollow Tree,” explains that ordinary Americans have been sold the lie that they are responsible for their own success, when really they are in thrall to corporations and the government doesn’t support them as it should. This message hits home for Sam, who is distressed about the precarious situation of the Latina dining hall employees she has met via her work study job. Both Elisabeth and Sam try to turn their privilege to the good, with varied results.

But fundamental differences between the two emerge, mostly to do with economics. Elisabeth comes from money and takes luxury products for granted, while Sam is solidly working-class and develops a surprising affinity with Elisabeth’s father-in-law, George, who is near bankruptcy after Uber killed off his car service business. His pet theory, “The Hollow Tree,” explains that ordinary Americans have been sold the lie that they are responsible for their own success, when really they are in thrall to corporations and the government doesn’t support them as it should. This message hits home for Sam, who is distressed about the precarious situation of the Latina dining hall employees she has met via her work study job. Both Elisabeth and Sam try to turn their privilege to the good, with varied results.

Although I remained engrossed in the main characters’ stories, which unfold in alternating chapters, I thought this could easily have been 300 pages instead of nearly 400. In particular, Sullivan belabours Sam’s uncertainty over her thirtysomething English fiancé, Clive, whom Elisabeth refers to as “sleazy-hot.” The red flags are more than obvious to others in Sam’s life, and to us as readers, yet we get scene after scene meant to cast shade on him. I also kept wondering if first person would have been the better delivery mode for one or both strands. Still, this was perfect literary cross-over summer reading. (Little Free Library)

Three on a Theme: Queer Family-Making

Several 2021 memoirs have given me a deeper understanding of the special challenges involved when queer couples decide they want to have children.

“It’s a fundamentally queer principle to build a family out of the pieces you have”

~Jennifer Berney

“That’s the thing[:] there are no accidental children born to homosexuals – these babies are always planned for, and always wanted.”

~Michael Johnson-Ellis

The Other Mothers by Jennifer Berney

Berney remembers hearing the term “test-tube baby” for the first time in a fifth-grade sex ed class taught by a lesbian teacher at her Quaker school. By that time she already had an inkling of her sexuality, so suspected that she might one day require fertility help herself.

By the time she met her partner, Kellie, she knew she wanted to be a mother; Kellie was unsure. Once they were finally on the same page, it wasn’t an easy road to motherhood. They purchased donated sperm through a fertility clinic and tried IUI, but multiple expensive attempts failed. Signs of endometriosis had doctors ready to perform invasive surgery, but in the meantime the couple had met a friend of a friend (Daniel, whose partner was Rebecca) who was prepared to be their donor. Their at-home inseminations resulted in a pregnancy – after two years of trying to conceive – and, ultimately, in their son. Three years later, they did the whole thing all over again. Rebecca had sons at roughly the same time, too, giving their boys the equivalent of same-age cousins – a lovely, unconventional extended family.

By the time she met her partner, Kellie, she knew she wanted to be a mother; Kellie was unsure. Once they were finally on the same page, it wasn’t an easy road to motherhood. They purchased donated sperm through a fertility clinic and tried IUI, but multiple expensive attempts failed. Signs of endometriosis had doctors ready to perform invasive surgery, but in the meantime the couple had met a friend of a friend (Daniel, whose partner was Rebecca) who was prepared to be their donor. Their at-home inseminations resulted in a pregnancy – after two years of trying to conceive – and, ultimately, in their son. Three years later, they did the whole thing all over again. Rebecca had sons at roughly the same time, too, giving their boys the equivalent of same-age cousins – a lovely, unconventional extended family.

It surprised me that the infertility business seemed entirely set up for heterosexual couples – so much so that a doctor diagnosed the problem, completely seriously, in Berney’s chart as “Male Factor Infertility.” This was in Washington state in c. 2008, before the countrywide legalization of gay marriage, so it’s possible the situation would be different now, or that the couple would have had a different experience had they been based somewhere like San Francisco where there is a wide support network and many gay-friendly resources.

Berney finds the joy and absurdity in their journey as well as the many setbacks. I warmed to the book as it went along: early on, it dragged a bit as she surveyed her younger years and traced the history of IVF and alternatives like international adoption. As the storyline drew closer to the present day, there was more detail and tenderness and I was more engaged. I’d read more from this author. (Published by Sourcebooks. Read via NetGalley)

small: on motherhoods by Claire Lynch

A line from Berney’s memoir makes a good transition into this one: “I felt a sense of dread: if I turned out to be gay I believed my life would become unbearably small.” The word “small” is a sort of totem here, a reminder of the microscopic processes and everyday miracles that go into making babies, as well as of the vulnerability of newborns – and of hope.

Lynch and her partner Beth’s experience in England was reminiscent of Berney’s in many ways, but with a key difference: through IVF, Lynch’s eggs were added to donor sperm to make the embryos implanted in Beth’s uterus. Mummy would have the genetic link, Mama the physical tie of carrying and birthing. It took more than three years of infertility treatment before they conceived their twin girls, born premature; they were followed by another daughter, creating a crazy but delightful female quintet. The account of the time when their daughters were in incubators reminded me of Francesca Segal’s Mother Ship.

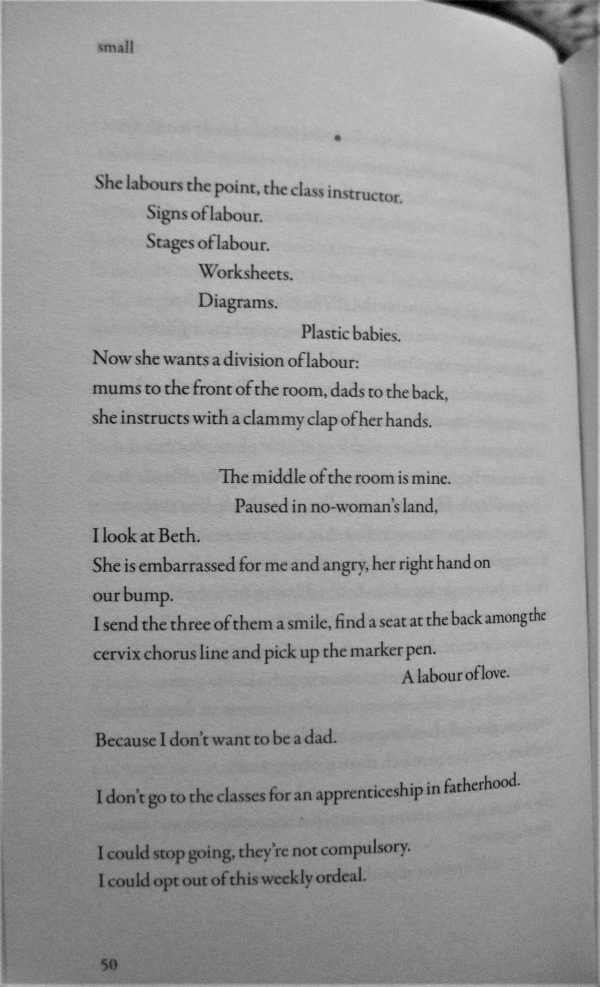

There are two intriguing structural choices that make small stand out. The first you’d notice from opening the book at random, or to page 1. It is written in a hybrid form, the phrases and sentences laid out more like poetry. Although there are some traditional expository paragraphs, more often the words are in stanzas or indented. Here’s an example of what this looks like on the page. It also happens to be from one of the most ironically funny parts of the book, when Lynch is grouped in with the dads at an antenatal class:

It’s a fast-flowing, artful style that may remind readers of Bernardine Evaristo’s work (and indeed, Evaristo gives one of the puffs). The second interesting decision was to make the book turn on a revelation: at the exact halfway mark we learn that, initially, the couple intended to have opposite roles: Lynch tried to get pregnant with Beth’s baby, but miscarried. Making this the pivot point of the memoir emphasizes the struggle and grief of this experience, even though we know that it had a happy ending.

With thanks to Brazen Books for the free copy for review.

How We Do Family by Trystan Reese

We mostly have Trystan Reese to thank for the existence of a pregnant man emoji. A community organizer who works on anti-racist and LGBTQ justice campaigns, Reese is a trans man married to a man named Biff. They expanded their family in two unexpected ways: first by adopting Biff’s niece and nephew when his sister’s situation of poverty and drug abuse meant she couldn’t take care of them, and then by getting pregnant in the natural (is that even the appropriate word?) way.

All along, Reese sought to be transparent about the journey, with a crowdfunding project and podcast ahead of the adoption, and media coverage of the pregnancy. This opened the family up to a lot of online hatred. I found myself most interested in the account of the pregnancy itself, and how it might have healed or exacerbated a sense of bodily trauma. Reese was careful to have only in-the-know and affirming people in the delivery room so there would be no surprises for anyone. His doctor was such an ally that he offered to create a more gender-affirming C-section scar (vertical rather than horizontal) if it came to it. How to maintain a sense of male identity while giving birth? Well, Reese told Biff not to look at his crotch during the delivery, and decided not to breastfeed.

All along, Reese sought to be transparent about the journey, with a crowdfunding project and podcast ahead of the adoption, and media coverage of the pregnancy. This opened the family up to a lot of online hatred. I found myself most interested in the account of the pregnancy itself, and how it might have healed or exacerbated a sense of bodily trauma. Reese was careful to have only in-the-know and affirming people in the delivery room so there would be no surprises for anyone. His doctor was such an ally that he offered to create a more gender-affirming C-section scar (vertical rather than horizontal) if it came to it. How to maintain a sense of male identity while giving birth? Well, Reese told Biff not to look at his crotch during the delivery, and decided not to breastfeed.

I realized when reading this and Detransition, Baby that my view of trans people is mostly post-op because of the only trans person I know personally, but a lot of people choose never to get surgical confirmation of gender (or maybe surgery is more common among trans women?). We’ve got to get past the obsession with genitals. As Reese writes, “we are just loving humans, like every human throughout all of time, who have brought a new life into this world. Nothing more than that, and nothing less. Just humans.”

This is a very fluid, quick read that recreates scenes and conversations with aplomb, and there are self-help sections after most chapters about how to be flexible and have productive dialogue within a family and with strangers. If literary prose and academic-level engagement with the issues are what you’re after, you’d want to head to Maggie Nelson’s The Argonauts instead, but I also appreciated Reese’s unpretentious firsthand view.

And here’s further evidence of my own bias: the whole time I was reading, I felt sure that Reese must be the figure on the right with reddish hair, since that looked like a person who could once have been a woman. But when I finished reading I looked up photos; there are many online of Reese during pregnancy. And NOPE, he is the bearded, black-haired one! That’ll teach me to make assumptions. (Published by The Experiment. Read via NetGalley)

Plus a bonus essay from the Music.Football.Fatherhood anthology, DAD:

“A Journey to Gay Fatherhood: Surrogacy – The Unimaginable, Manageable” by Michael Johnson-Ellis

The author and his husband Wes had both previously been married to women before they came out. Wes already had a daughter, so they decided Johnson-Ellis would be the genetic father the first time. They then had different egg donors for their two children, but used the same surrogate for both pregnancies. I was astounded at the costs involved: £32,000 just to bring their daughter into being. And it’s striking both how underground the surrogacy process is (in the UK it’s illegal to advertise for a surrogate) and how exclusionary systems are – the couple had to fight to be in the room when their surrogate gave birth, and had to go to court to be named the legal guardians when their daughter was six weeks old. Since then, they’ve given testimony at the Houses of Parliament and become advocates for UK surrogacy.

The author and his husband Wes had both previously been married to women before they came out. Wes already had a daughter, so they decided Johnson-Ellis would be the genetic father the first time. They then had different egg donors for their two children, but used the same surrogate for both pregnancies. I was astounded at the costs involved: £32,000 just to bring their daughter into being. And it’s striking both how underground the surrogacy process is (in the UK it’s illegal to advertise for a surrogate) and how exclusionary systems are – the couple had to fight to be in the room when their surrogate gave birth, and had to go to court to be named the legal guardians when their daughter was six weeks old. Since then, they’ve given testimony at the Houses of Parliament and become advocates for UK surrogacy.

(I have a high school acquaintance who has gone down this route with his husband – they’re about to meet their daughter and already have a two-year-old son – so I was curious to know more about it, even though their process in the USA might be subtly different.)

On the subject of queer family-making, I have also read: The Argonauts by Maggie Nelson ( ) and The Fixed Stars by Molly Wizenberg (

) and The Fixed Stars by Molly Wizenberg ( ).

).

If you read just one … Claire Lynch’s small was the one I enjoyed most as a literary product, but if you want to learn more about the options and process you might opt for Jennifer Berney’s The Other Mothers; if you’re particularly keen to explore trans issues and LGTBQ activism, head to Trystan Reese’s How We Do Family.

Have you read anything on this topic?

Childless Voices by Lorna Gibb

People end up not having children for any number of reasons: medical issues, bereavement, a lack of finances, not having a partner at the right time, or the simple decision not to become a parent. The subtitle of Lorna Gibb’s Childless Voices acknowledges these various routes: “Stories of Longing, Loss, Resistance and Choice.”

For Gibb, a university lecturer, biographer and novelist, the childless state was involuntary, a result of severe endometriosis that led to infertility and early menopause. Although this has been a source of sadness for her and her husband, she knows that she has it easy compared to women in other parts of the world. Through her research and Skype interviews, she hears horrific stories about infertile women who meet with domestic violence and social ostracism and are sometimes driven to suicide. In Ghana childless women can be branded as witches and exiled. Meanwhile, some are never given the chance to have the children they might long for: Gibb cites China’s one-child policy, female genital mutilation, and enforced sterilization programs like those of the Roma in Yugoslavia and the Quechua in Peru.

For Gibb, a university lecturer, biographer and novelist, the childless state was involuntary, a result of severe endometriosis that led to infertility and early menopause. Although this has been a source of sadness for her and her husband, she knows that she has it easy compared to women in other parts of the world. Through her research and Skype interviews, she hears horrific stories about infertile women who meet with domestic violence and social ostracism and are sometimes driven to suicide. In Ghana childless women can be branded as witches and exiled. Meanwhile, some are never given the chance to have the children they might long for: Gibb cites China’s one-child policy, female genital mutilation, and enforced sterilization programs like those of the Roma in Yugoslavia and the Quechua in Peru.

Gibb is admirably comprehensive here, considering every possible aspect of childlessness. Particularly interesting are the different cultural adaptations childless women make. Certain countries allow polygamy, giving a second wife a chance to bear children on behalf of an infertile one; Kenya and other parts of sub-Saharan Africa recognize ‘marriages’ between childless women so they can create a family and support system. In Albania being a “sworn virgin” is an old and venerable custom. And, of course, there are any number of support groups and online communities. The situation of those who were once parents but are no longer is especially wrenching. Stillbirth only started to be talked about in the 1980s, Gibb notes, but even today is seen as a lesser loss than that of a child who dies later in life.

The author believes there is societal injustice in terms of who has access to fertility treatment and how the state deals with childless people. In the UK, she characterizes IVF as a “postcode lottery”: where you live often determines how many free cycles you’re entitled to on the NHS. In the USA, meanwhile, fertility treatment is so expensive that only those with a certain level of wealth can consider it. The childless may also feel ‘punished’ by tax breaks that favor parents and workplaces that expect non-parents to work unsociable hours. In a sense, then, the childless contribute more but benefit less.

Chosen childlessness is perhaps given short shrift at just 32 pages out of 239. However, it’s still a very thorough treatment of the reasons why couples decide not to become parents, including cultural norms, career goals, self-knowledge and environmental concerns. No surprise that this was the chapter that resonated with me the most. I also especially enjoyed the personal interludes (all titled “A Short Note on…”) in which Gibb celebrates her feminist, childless heroes like Frida Kahlo and Anaïs Nin and writes about how much becoming a godmother meant to her but also of the sadness of seeing a good friend’s teenage son die of a brain tumor.

By coincidence, I’ve recently read another book on the same topic: Do You Have Kids? Life when the Answer Is No, by Kate Kaufmann (coming out in America next month). Gibb primarily traces the many different reasons for childlessness; Kaufmann mostly addresses the question of “now what?” – how women without children approach careers, wider family life, housing options, spirituality and the notion of leaving a legacy. Gibb’s approach is international and comparative, while Kaufmann’s is largely specific to the USA. Though the two authors are childless due to endometriosis and infertility, they feel sisterhood with women who never became mothers for whatever reason. I’d say these two books are complementary rather than rivals, and reveal valuable perspectives that can sometimes be overlooked.

By coincidence, I’ve recently read another book on the same topic: Do You Have Kids? Life when the Answer Is No, by Kate Kaufmann (coming out in America next month). Gibb primarily traces the many different reasons for childlessness; Kaufmann mostly addresses the question of “now what?” – how women without children approach careers, wider family life, housing options, spirituality and the notion of leaving a legacy. Gibb’s approach is international and comparative, while Kaufmann’s is largely specific to the USA. Though the two authors are childless due to endometriosis and infertility, they feel sisterhood with women who never became mothers for whatever reason. I’d say these two books are complementary rather than rivals, and reveal valuable perspectives that can sometimes be overlooked.

My rating:

Childless Voices was published by Granta on February 7th. My thanks to the publisher for the free copy for review.

Jones is now a mother of three. You might think delivery would get easier each time, but in fact the birth of her second son was worst, physically: she had to go into immediate surgery for a fourth-degree anal sphincter tear. In reflecting on her own experiences, and speaking with experts, she has become passionate about fostering open discussion about the pain and risk of childbirth, and how to mitigate them. Women who aren’t informed about what they might go through suffer more because of the shock and isolation. There’s the medical side, but also the equally important social implications: new mothers need so much more practical and mental health support, and their unpaid care work must be properly valued by society. “Yet the focus remains on individual responsibility, maintaining the illusion that we are impermeable, impenetrable machines, disconnected from the world around us.”

Jones is now a mother of three. You might think delivery would get easier each time, but in fact the birth of her second son was worst, physically: she had to go into immediate surgery for a fourth-degree anal sphincter tear. In reflecting on her own experiences, and speaking with experts, she has become passionate about fostering open discussion about the pain and risk of childbirth, and how to mitigate them. Women who aren’t informed about what they might go through suffer more because of the shock and isolation. There’s the medical side, but also the equally important social implications: new mothers need so much more practical and mental health support, and their unpaid care work must be properly valued by society. “Yet the focus remains on individual responsibility, maintaining the illusion that we are impermeable, impenetrable machines, disconnected from the world around us.” Kinsella is an Irish poet who became a mother in her mid-twenties; that’s young these days. In unchronological vignettes dated in relation to her son’s birth – the number of months after; negative numbers to indicate that it happened before – she explores her personality, mental health and bodily experiences, but also comments more widely on Irish culture (the stereotype of the ‘mammy’; the only recent closure of Magdalene laundries and overturning of anti-abortion laws) and theories about motherhood.

Kinsella is an Irish poet who became a mother in her mid-twenties; that’s young these days. In unchronological vignettes dated in relation to her son’s birth – the number of months after; negative numbers to indicate that it happened before – she explores her personality, mental health and bodily experiences, but also comments more widely on Irish culture (the stereotype of the ‘mammy’; the only recent closure of Magdalene laundries and overturning of anti-abortion laws) and theories about motherhood. I’ve read one of Kirsty Logan’s novels and dipped into her short stories. I immediately knew her parenting memoir would be up my street, but wondered how her fantasy/horror style might translate into nonfiction. Second-person narration is perfect for describing her journey into motherhood: a way of capturing the bewildering weirdness of this time but also forcing the reader to experience it firsthand. It is, in a way, as feminist and surreal as her other work. “You and your partner want a baby. But your two bodies can’t make a baby together. So you need some sperm.” That opening paragraph is a jolt, and the frank present-tense storytelling carries all through.

I’ve read one of Kirsty Logan’s novels and dipped into her short stories. I immediately knew her parenting memoir would be up my street, but wondered how her fantasy/horror style might translate into nonfiction. Second-person narration is perfect for describing her journey into motherhood: a way of capturing the bewildering weirdness of this time but also forcing the reader to experience it firsthand. It is, in a way, as feminist and surreal as her other work. “You and your partner want a baby. But your two bodies can’t make a baby together. So you need some sperm.” That opening paragraph is a jolt, and the frank present-tense storytelling carries all through. Procreation. Duplication. Imitation. All three connotations are appropriate for the title of an allusive novel about motherhood and doppelgangers. A pregnant writer starts composing a novel about Mary Shelley and finds the borders between fiction and (auto)biography blurring: “parts of her story detached themselves from the page and clung to my life.” The first long chapter, “Conception,” is full of biographical information about Shelley and the writing and plot of Frankenstein, chiming with

Procreation. Duplication. Imitation. All three connotations are appropriate for the title of an allusive novel about motherhood and doppelgangers. A pregnant writer starts composing a novel about Mary Shelley and finds the borders between fiction and (auto)biography blurring: “parts of her story detached themselves from the page and clung to my life.” The first long chapter, “Conception,” is full of biographical information about Shelley and the writing and plot of Frankenstein, chiming with