Tag Archives: Kamila Shamsie

The BBC National Short Story Award 2025 Anthology

Another quick contribution to #ShortStorySeptember. I was delighted when Comma Press sent me a surprise copy of The BBC National Short Story Award 2025, which prints the five stories shortlisted for this year’s prize.

Now in its 20th year, the award has recognised established authors and newcomers alike – the roster of winners includes Lucy Caldwell, Sarah Hall (twice), Cynan Jones, James Lasdun, KJ Orr, Ingrid Persaud, Ross Raisin, Lionel Shriver and Naomi Wood – and the £15,000 prize money is very generous indeed for a single story.

This very evening, the winner will be announced live on the BBC Radio 4 Front Row programme (it starts at 7:15 p.m. if you’re in the UK). I’ll update my post later with news of the winner. For now, here are my brief thoughts on the five stories and which I hope will win.

“You Cannot Thread a Moving Needle” is an excerpt from Colwill Brown’s linked short story collection, We Pretty Pieces of Flesh. It’s in broad Doncaster dialect and written in the second person, thus putting the reader into the position of a young woman who is often pressured – by men and by the prevailing standards of beauty – into uncomfortable situations. It’s all drinking and sex and feeling in competition with other girls. ‘You’ grow up limited and bitter and wondering if revenge is possible. This was admirable for its gritty realism but not pleasant per se, and convinced me I don’t want to read the whole book.

“Little Green Man” by Edward Hogan begins with a classic scenario of two very different people being thrown together. Carrie stands out not just for being nearly six feet tall but also for being the only woman working for Parks and Gardens in Derby. One morning she’s assigned a temporary apprentice, Ryan, who is half her age and might be dismissed with one look as being no good (“lines shaved into his eyebrows … dyed blond hair” and a baby at home). But their interactions go beyond stereotypes as we learn of Ryan’s ambitions and his disapproving dad; and of Carrie’s ex, Bridget, who wanted more spontaneity. It’s a solid, feel-good story about not making your mind up about people, in the vein of Groundskeeping.

“Yair” by Emily Abdeni-Holman is another two-character drama, with the title figure an Israeli estate agent who takes the female narrator looking for an apartment in Jerusalem in 2018. Sexual tension and conflicting preconceived notions are crackling between them. A simple story with an autofiction feel, it reminded me of writing by Sigrid Nunez and Elizabeth Strout and exposes the falsity of facile us-and-them distinctions.

“Two Hands” by Caoilinn Hughes is a three-player comedy starring a married couple and their driving instructor. After a motorway crash in the beloved Fiat Panda they brought with them from Italy when they moved back to Ireland, Desmond and Gemma are in need of some renewed confidence behind the wheel. They talk about work – Des’s ancient archaeology research, Gemma’s translations – but not about the accident, which clearly is still affecting them both. Meanwhile, their late-seventies instructor is a War and Peace-reading calm presence whose compassion stretches only so far. I found this sharp, witty and original, just like Hughes’s Orchid & the Wasp.

Last but not least, “Rain: a history” by Andrew Miller is set in a sodden near-future English village. The protagonist has been having heart trouble and failing to connect with his traumatized teenage son. Nothing in his house or on his person ever feels dry. Their surroundings are menacing and desolate, yet still somehow beautiful. A letter came through the door last week, inviting everyone to meet in the parish church this evening. What can be done? Perhaps solidarity is as much as they, and we, can hope for. This was spare and haunting, and so much better than The Land in Winter.

I thoroughly enjoyed reading these entries and wouldn’t mind four out of the five winning. My sense of the spirit of the award is that it should go to a stand-alone story by an up-and-coming author. It’s hard to say what judges William Boyd, Lucy Caldwell, Ross Raisin, Kamila Shamsie and Di Speirs will go for: realism, novelty, subtlety, humour or prophecy? My personal favourite was “Yair,” but I have an inkling the award might go to Caoilinn Hughes and I would be very happy with that result as well.

With thanks to Comma Press for the free copy for review.

UPDATE: The winner was … the story I enjoyed the least, “You Cannot Thread a Moving Needle.” Nonetheless, I acknowledge that Colwill Brown has a distinctive voice.

20 Books of Summer, 7–9: Furies, The Earthquake Bird, and Greta & Valdin

It might seem that I’m very behind on 20 Books of Summer, and I am, but that’s mostly because I’ve done my usual trick of starting loads of books at once so that I’m currently in the middle of another nine with no prospect of finishing any particularly soon. I will eventually review more, but probably all in a rush and on the later side. It doesn’t help that quite a few happen to be lacklustre reads, such that I have to push myself through them instead of enjoying spending time with the stack. For today, though, I have a pretty readable trio made up of feminist short stories, a mild Japan-set mystery, and a highly random queer dysfunctional family novel that rose from indie obscurity in New Zealand. (Also a DNF.)

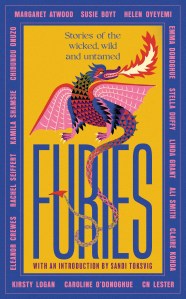

Furies: Stories of the Wicked, Wild and Untamed (2023)

It was my second attempt at this Virago anthology; I borrowed it from the library last year but never opened it, as far as I can remember. Each story is named after a synonym for “virago,” so the focus is on strong and unconventional women, but given that brief there is huge variety, including memoir (Ali Smith’s “Spitfire,” about her late mother’s WAAF service), historical research (CN Lester on sexology and early trans figures, Emma Donoghue on early-twentieth-century activist and lesbian Kathlyn Oliver, Stella Duffy on menopause) and even one graphic short, the mother–daughter horror story “She-Devil” by comics artist Eleanor Crewes.

As with any anthology, some pieces stand out more than others. Caroline O’Donoghue, Helen Oyeyemi and Kamila Shamsie’s contributions were unlikely to convert me into a fan. Margaret Atwood is ever sly and accessible, with “Siren” opening with the line “Today’s Liminal Beings Knitting Circle will now be called to order.” I was surprised to get on really well with Kirsty Logan’s “Wench,” about girls ostracized by their religious community because of their desire for each other – I’ll have to read Now She Is Witch, as it’s set in the same fictional world – and Chibundu Onuzo’s “Warrior,” about Deborah, an Israelite leader in the book of Judges. And while I doubt I need to read a whole novel by Rachel Seiffert, I did enjoy “Fury,” about a group of Polish women who fended off Nazi invaders.

As with any anthology, some pieces stand out more than others. Caroline O’Donoghue, Helen Oyeyemi and Kamila Shamsie’s contributions were unlikely to convert me into a fan. Margaret Atwood is ever sly and accessible, with “Siren” opening with the line “Today’s Liminal Beings Knitting Circle will now be called to order.” I was surprised to get on really well with Kirsty Logan’s “Wench,” about girls ostracized by their religious community because of their desire for each other – I’ll have to read Now She Is Witch, as it’s set in the same fictional world – and Chibundu Onuzo’s “Warrior,” about Deborah, an Israelite leader in the book of Judges. And while I doubt I need to read a whole novel by Rachel Seiffert, I did enjoy “Fury,” about a group of Polish women who fended off Nazi invaders.

A few of my favourites were “Harridan” by Linda Grant, about an older woman who frightens the young couple who share her flat’s garden during lockdown (“this old lady, this hag she sees, this bitter travesty of her celestial youth and beauty is not her. Inside she’s a flame, she’s a pistol”); “Muckraker” by Susie Boyt, in which a woman makes conquests of breast cancer widowers; and “Tygress” by Claire Kohda, where the stereotype of the Asian ‘tiger mother’ turns literal. Duffy’s “Dragon” closes the collection with a very interesting blend of autofiction, interviews and medical reportage about different experiences of objectification in youth and invisibility in ageing. It brings the whole together nicely: “Tell me your tale and, in the telling, feel it all drop away. You are, and you are not, your story. Keep what serves you now, make space for new maybes.” (Free from a neighbour) ![]()

The Earthquake Bird: A Novel of Mystery by Susanna Jones (2001)

Susanna Jones’s When Nights Are Cold is one of my favourite novels that no one else has ever heard of, so I jumped at the chance to buy a bargain copy of her debut back in 2020. Lucy Fly has lived in Tokyo for ten years, working as a translator of machinery manuals. She wanted to get as far away as possible from her conventional family of six brothers, so she’s less than thrilled to meet fellow Yorkshire lass Lily Bridges, a nurse new to the country and looking for someone to help her find an apartment and learn some basic Japanese. Lucy is a prickly loner with only a few friends – and a lover, photographer Teiji – but she reluctantly agrees to be Lily’s guide.

Susanna Jones’s When Nights Are Cold is one of my favourite novels that no one else has ever heard of, so I jumped at the chance to buy a bargain copy of her debut back in 2020. Lucy Fly has lived in Tokyo for ten years, working as a translator of machinery manuals. She wanted to get as far away as possible from her conventional family of six brothers, so she’s less than thrilled to meet fellow Yorkshire lass Lily Bridges, a nurse new to the country and looking for someone to help her find an apartment and learn some basic Japanese. Lucy is a prickly loner with only a few friends – and a lover, photographer Teiji – but she reluctantly agrees to be Lily’s guide.

We know from the start that Lucy is in custody being questioned about events leading up to Lily’s murder. She refuses to tell the police anything, but what we are reading is her confession, in which she does eventually tell all. We learn that there have already been three accidental deaths among her family and acquaintances – she seems cursed to attract them – and that her feelings about Lily changed over the months she showed the woman around. This short and reasonably compelling book gives glimpses of mountain scenery, noodle bars, and spartan apartments. Perhaps inevitably, it reminded me a bit of Murakami. It’s hard to resist an unreliable narrator. However, I felt Jones’s habit of having Lucy speak of herself in the third person was overdone. (Secondhand – Broad Street Book Centre, Hay-on-Wye) ![]()

Greta & Valdin by Rebecca K Reilly (2021; 2024)

The title characters are a brother and sister in their late twenties who share a flat and a tendency to sabotage romantic relationships. Both are matter-of-factly queer and biracial (Māori/Russian). The novel flips back and forth between their present-tense first-person narration with each short chapter. It takes quite a while to pick up on who is who in the extended Vladisavljevic clan and their New Zealand university milieu (their father is a science professor and Greta an English department PhD and tutor), so I was glad of the character list at the start.

The title characters are a brother and sister in their late twenties who share a flat and a tendency to sabotage romantic relationships. Both are matter-of-factly queer and biracial (Māori/Russian). The novel flips back and forth between their present-tense first-person narration with each short chapter. It takes quite a while to pick up on who is who in the extended Vladisavljevic clan and their New Zealand university milieu (their father is a science professor and Greta an English department PhD and tutor), so I was glad of the character list at the start.

I was expecting a breezy, snarky read and to an extent that’s what I got. Not a whole lot happens; situations advance infinitesimally through quirky dialogue thick with pop culture references. There are some quite funny one-liners, but the plot is so meandering and the voices so deadpan that I struggled to remain engaged. (On her website, Reilly, who is Māori, ascribes the book’s randomness to her neurodivergence.)

The protagonists seem so affectedly cynical that when they exhibit strong feelings for new partners, you’re a bit taken aback. Really, Reilly can do serious? One of the siblings is reunited with a former partner and starts to think about settling down and even adopting a child. This is the last novel I would have expected to end with a wedding, but so it does. If you’re a big fan of Elif Batuman and Naoise Dolan, this might be up your street. Below are some sample lines that should help you make up your mind (quotes unattributed to minimize spoilers). ![]()

I don’t really feel like anything these days, just a beautiful husk filled with opinions about globalism and a strong desire to go out for dinner.

I don’t think you’re the weirdest person I’ve ever met even though you do sometimes talk like a philosophical narrator in an independent film.

I’m trying to write my wedding speech, so I don’t go off on a tangent and start listing my favourite Arnold Schwarzenegger movies. I was thinking I could write an acrostic poem, but I’ve made the foolish decision of marrying someone whose name begins with X.

With thanks to Hutchinson Heinemann (Penguin Random House) for the free copy for review.

And a DNF:

The Lost Love Songs of Boysie Singh by Ingrid Persaud – I thought Persaud’s debut novel, Love after Love, was fantastic, but I was right to be daunted by the length of this follow-up. The strategy is similar to that in Mrs. Hemingway by Naomi Wood: giving sideways looks at a famous man through the women he collected around him. John Boysie Singh was a real-life Trinidadian gangster who was hanged for his crimes in 1957 (as the article reprinted on the first page reveals). The major problem here is that all four of the dialect voices sound much the same, so I couldn’t tell them apart. Each time I opened the book, I had to look back at the blurb to be reminded that Popo was his prostitute mistress while Mana Lala was the mother of his son Chunksee. In the 103 pages I read (less than one-fifth of the total), there were so few chapters by Doris and Rosie that I never got a handle on who they were. Nor did I come to understand, or care about, Boysie. The editor needed to make drastic changes to this to ensure widespread readability. (Signed copy won in a Faber Instagram giveaway)

The Lost Love Songs of Boysie Singh by Ingrid Persaud – I thought Persaud’s debut novel, Love after Love, was fantastic, but I was right to be daunted by the length of this follow-up. The strategy is similar to that in Mrs. Hemingway by Naomi Wood: giving sideways looks at a famous man through the women he collected around him. John Boysie Singh was a real-life Trinidadian gangster who was hanged for his crimes in 1957 (as the article reprinted on the first page reveals). The major problem here is that all four of the dialect voices sound much the same, so I couldn’t tell them apart. Each time I opened the book, I had to look back at the blurb to be reminded that Popo was his prostitute mistress while Mana Lala was the mother of his son Chunksee. In the 103 pages I read (less than one-fifth of the total), there were so few chapters by Doris and Rosie that I never got a handle on who they were. Nor did I come to understand, or care about, Boysie. The editor needed to make drastic changes to this to ensure widespread readability. (Signed copy won in a Faber Instagram giveaway)

Women’s Prize 2023: Longlist Predictions vs. Wishes

I’ve been working on a list of novels eligible for this year’s Women’s Prize since … this time last year. Unusual for me to be so prepared! It shows how invested I’ve become in this prize over the years. For instance, last year my book club was part of an official shadowing scheme, which was great fun.

We’re now less than a month out from the longlist, which will be announced on 7 March. Like last year, I’ve separated my predictions from a wish list; two titles overlap. Here’s a reminder of the parameters, taken from the website:

“Any woman writing in English – whatever her nationality, country of residence, age or subject matter – is eligible. Novels must be published in the United Kingdom between 1 April in the year the Prize calls for entries, and 31 March the following year, when the Prize is announced. … The Prize only accepts novels entered by publishers, who may each submit a maximum of two titles per imprint, depending on size, and one title for imprints with a list of ten fiction titles or fewer published in a year. Previously shortlisted and winning authors are given a ‘free pass’.”

This year I dutifully kept tabs on publisher quotas as I compiled my lists. I also attempted to bear in mind the interests of this year’s judges (also from the website): “Chair of Judges, author and journalist Louise Minchin, is joined by award-winning novelist Rachel Joyce; author, journalist and podcaster Irenosen Okojie; bestselling author and journalist Bella Mackie and MP for Hampstead and Kilburn Tulip Siddiq.”

Predictions

A Spell of Good Things, Ayọ̀bámi Adébáyọ̀

Birnam Wood, Eleanor Catton

Joan, Katherine J. Chen

Maame, Jessica George

Really Good, Actually, Monica Heisey

Trespasses, Louise Kennedy

The Night Ship, Jess Kidd (my review)

Demon Copperhead, Barbara Kingsolver (my review)

Our Missing Hearts, Celeste Ng (my review)

The Marriage Portrait, Maggie O’Farrell

I’m a Fan, Sheena Patel

Elektra, Jennifer Saint

Best of Friends, Kamila Shamsie

River Sing Me Home, Eleanor Shearer

Lucy by the Sea, Elizabeth Strout – currently reading

Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, Gabrielle Zevin (my review)

Wish List

How Not to Drown in a Glass of Water, Angie Cruz

The Weather Woman, Sally Gardner (my review)

Maame, Jessica George

The Great Reclamation, Rachel Heng

Bad Cree, Jessica Johns

I Have Some Questions for You, Rebecca Makkai – currently reading

Sea of Tranquillity, Emily St. John Mandel (my review)

The Hero of This Book, Elizabeth McCracken (my review)

Nightcrawling, Leila Mottley (my review)

We All Want Impossible Things, Catherine Newman – currently reading

Everything the Light Touches, Janice Pariat (my review)

Camp Zero, Michelle Min Sterling – review pending for Shelf Awareness

Briefly, A Delicious Life, Nell Stevens (my review)

This Time Tomorrow, Emma Straub (my review)

Fight Night, Miriam Toews – currently reading

Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, Gabrielle Zevin (my review)

Of course, even if I’m lucky, I’ll still only get a few right across these two lists, and I’ll be kicking myself over the ones I considered but didn’t include, and marvelling at all the ones I’ve never heard of…

What would you like to see on the longlist?

~BREAKING NEWS: There are plans afoot to start a Women’s Prize for Non-Fiction. Now seeking funding to start in 2024. More details here.~

Appendix

(A further 99 eligible novels that were on my radar but didn’t make the cut:)

Hester, Laurie Lico Albanese

Rose and the Burma Sky, Rosanna Amaka

Milk Teeth, Jessica Andrews

Clara & Olivia, Lucy Ashe

Wet Paint, Chloë Ashby

Shrines of Gaiety, Kate Atkinson

Honey & Spice, Bolu Babalola

Hell Bent, Leigh Bardugo

Either/Or, Elif Batuman

Girls They Write Songs About, Carlene Bauer

seven steeples, Sara Baume

The Witches of Vardo, Anya Bergman

Shadow Girls, Carol Birch

Permission, Jo Bloom

Horse, Geraldine Brooks

Glory, NoViolet Bulawayo

Mother’s Day, Abigail Burdess

Instructions for the Working Day, Joanna Campbell

People Person, Candice Carty-Williams

Disorientation, Elaine Hsieh Chou

The Book of Eve, Meg Clothier

Cult Classic, Sloane Crosley

The Things We Do to Our Friends, Heather Darwent

The Bewitching, Jill Dawson

Common Decency, Susannah Dickey

Theatre of Marvels, L.M. Dillsworth

Haven, Emma Donoghue

History Keeps Me Awake at Night, Christy Edwall

The Candy House, Jennifer Egan

Dazzling, Chikodili Emelumadu

You Made a Fool of Death with Your Beauty, Akwaeke Emezi

there are more things, Yara Rodrigues Fowler

Factory Girls, Michelle Gallen

Lessons in Chemistry, Bonnie Garmus

The Illuminated, Anindita Ghose

Your Driver Is Waiting, Priya Guns

The Rabbit Hutch, Tess Gunty

The Dance Tree, Kiran Millwood Hargrave

Weyward, Emilia Hart

Other People Manage, Ellen Hawley

Stone Blind, Natalie Haynes

The Cloisters, Katy Hays

Motherthing, Ainslie Hogarth

The Unfolding, A.M. Homes

The White Rock, Anna Hope

They’re Going to Love You, Meg Howrey

Housebreaking, Colleen Hubbard

Vladimir, Julia May Jonas

This Is Gonna End in Tears, Liza Klaussmann

The Applicant, Nazli Koca

Babel, R.F. Kuang

Yerba Buena, Nina Lacour

The Swimmers, Chloe Lane

The Book of Goose, Yiyun Li

Amazing Grace Adams, Fran Littlewood

All the Little Bird Hearts, Viktoria Lloyd-Barlow

Now She Is Witch, Kirsty Logan

The Chosen, Elizabeth Lowry

The Home Scar, Kathleen MacMahon

Very Cold People, Sarah Manguso

All This Could Be Different, Sarah Thankam Mathews

Becky, Sarah May

The Dog of the North, Elizabeth McKenzie

Dinosaurs, Lydia Millet

Young Women, Jessica Moor

The Garnett Girls, Georgina Moore

Black Butterflies, Priscilla Morris

Lapvona, Ottessa Moshfegh

Someone Else’s Shoes, Jojo Moyes

The Men, Sandra Newman

True Biz, Sara Nović

Babysitter, Joyce Carol Oates

Tomorrow I Become a Woman, Aiwanose Odafen

Things They Lost, Okwiri Oduor

The Human Origins of Beatrice Porter and Other Essential Ghosts, Soraya Palmer

The Things that We Lost, Jyoti Patel

Still Water, Rebecca Pert

Stargazer, Laurie Petrou

Ruth & Pen, Emilie Pine

Delphi, Clare Pollard

The Whalebone Theatre, Joanna Quinn

The Poet, Louisa Reid

Carrie Soto Is Back, Taylor Jenkins Reid

Kick the Latch, Kathryn Scanlan

Blue Hour, Sarah Schmidt

After Sappho, Selby Wynn Schwartz

Signal Fires, Dani Shapiro

A Dangerous Business, Jane Smiley

Companion Piece, Ali Smith

Memphis, Tara M. Stringfellow

Flight, Lynn Steger Strong

Brutes, Dizz Tate

Madwoman, Louisa Treger

I Laugh Me Broken, Bridget van der Zijpp

I’m Sorry You Feel That Way, Rebecca Wait

The Schoolhouse, Sophie Ward

Sweet, Soft, Plenty Rhythm, Laura Warrell

The Odyssey, Lara Williams

A Complicated Matter, Anne Youngson

Avalon, Nell Zink

Final Thoughts on the Booker Longlist

On Wednesday the 13th the Man Booker Prize shortlist will be announced. I’d already reviewed six of the nominees and abandoned one; in the time since the longlist announcement I’ve only managed to read another one and a bit. That leaves four I didn’t get a chance to experience. Here’s a run-through of the 13 nominees, with my brief thoughts on each.

4 3 2 1 by Paul Auster (US) (Faber & Faber): I can’t see myself reading this one any time soon; I’ll choose a shorter work to be my first taste of Auster’s writing. I’ve heard mostly good reports, though.

Days Without End by Sebastian Barry (Ireland) (Faber & Faber): Read in March 2017. This is my overall favorite from the longlist so far. (See my BookBrowse review.) However, it’s already been recognized with the Costa Prize and the Walter Scott Prize for historical fiction, so if it doesn’t make the Booker shortlist I certainly won’t be crushed.

History of Wolves by Emily Fridlund (US) (Weidenfeld & Nicolson): Read in March 2017. A slow-building coming-of-age story with a child’s untimely death at its climax. Fridlund’s melancholy picture of outsiders whose skewed thinking leads them to transgress moral boundaries recalls Lauren Groff and Marilynne Robinson. (Reviewed for the Times Literary Supplement;  )

)

Exit West by Mohsin Hamid (Pakistan-UK) (Hamish Hamilton): I don’t have much interest in reading this one at this point; I didn’t get far in the one book I tried by Hamid (The Reluctant Fundamentalist) earlier this year. I’ve encountered mixed reviews.

Solar Bones by Mike McCormack (Ireland) (Canongate): If you’ve heard anything about this, it’s probably that the entire book is composed of one sentence. Now here’s an embarrassing admission: I didn’t make it past the first page.

Reservoir 13 by Jon McGregor (UK) (4th Estate): I read the first 15% last month and set it aside. I knew what to expect – lovely descriptions of the natural world and the daily life of a small community – but I guess hadn’t fully heeded the warning that nothing much happens. I won’t rule out trying this one again in the future, but for now it couldn’t hold my interest.

Elmet by Fiona Mozley (UK) (JM Originals): Read in August 2017. Simply terrific. (See my full blog review.) Overall, this dark horse selection is in second place for me. I’d love to see it make it through to the shortlist.

The Ministry of Utmost Happiness by Arundhati Roy (India) (Hamish Hamilton): I was never a huge fan of The God of Small Things, so this is another I’m not too keen to try.

Lincoln in the Bardo by George Saunders (US) (Bloomsbury Publishing): Read in April 2017. An entertaining and original treatment of life’s transience. I enjoyed the different registers Saunders uses for his characters, but was less convinced about snippets from historical texts. So audacious it deserves a shortlist spot; I wouldn’t mind it winning.

Home Fire by Kamila Shamsie (UK-Pakistan) (Bloomsbury Circus): This is the one book from the longlist that I most wish I’d gotten a chance to read. It’s been widely reviewed in the press as well as in the blogging world (A life in books, Elle Thinks, and Heavenali), generally very enthusiastically.

Autumn by Ali Smith (UK) (Hamish Hamilton): Read in November 2016. (See my blog review.) While some of Smith’s strengths benefit from immediacy – a nearly stream-of-consciousness style (no speech marks) and jokey dialogue – I’d prefer a more crafted narrative. In places this was repetitive, with the seasonal theme neither here nor there.

Swing Time by Zadie Smith (UK) (Hamish Hamilton): Read in October 2016 for a BookBrowse review. The Africa material wasn’t very convincing, and the Aimee subplot and the way Tracey turns out struck me as equally clichéd. The claustrophobic narration makes this feel insular. A disappointment compared to White Teeth and On Beauty.

The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead (US) (Fleet): Read in July 2017. (See my blog review.) I’m surprised such a case has been made for the uniqueness of this novel based on a simple tweak of the historical record. I felt little attachment to Cora and had to force myself to keep plodding through her story. Every critic on earth seems to love it, though.

If I had to take a guess at which six books will make it through Wednesday and why, I’d say:

- 4 3 2 1 by Paul Auster – A chunkster by a well-respected literary lion.

- Exit West by Mohsin Hamid – A timely refugee theme and a touch of magic realism.

- Solar Bones by Mike McCormack – Irish stream-of-consciousness. Channel James Joyce and you’ll impress all the literary types.

- Lincoln in the Bardo by George Saunders – Effusive in tone and cutting-edge in form.

- Autumn by Ali Smith – Captures the post-Brexit moment.

- The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead – Though it’s won every prize going, the judges probably think they’d be churlish to pass it by.

By contrast, if I were asked for the six I would prefer to be on the shortlist, and why, it’d be:

- Days Without End by Sebastian Barry – Pretty much unforgettable.

- History of Wolves by Emily Fridlund – A haunting novel that deserves more attention.

- Reservoir 13 by Jon McGregor – Though it’s not my personal favorite, I support McGregor.

- Elmet by Fiona Mozley – A nearly flawless debut. Give the gal a chance.

- Lincoln in the Bardo by George Saunders – Show-offy, but such fun to read.

- Home Fire by Kamila Shamsie – Timely and well crafted, by all accounts.

That would be three men and three women, if not the best mix of countries. I’d be happy with that list.