#MARM2025 and #NovNov25: The Penelopiad by Margaret Atwood (2005)

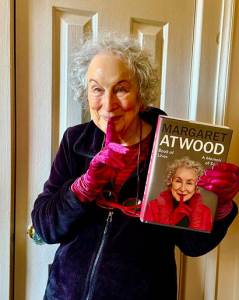

It’s my eighth time participating in the annual Margaret Atwood Reading Month (#MARM) hosted by indomitable Canadian blogger Marcie of Buried in Print. In previous years, I’ve read Surfacing and The Edible Woman, The Robber Bride and Moral Disorder, Wilderness Tips, The Door, Bodily Harm and Stone Mattress, and Life Before Man and Interlunar; and reread The Blind Assassin. Novembers are my excuse to catch up on the soon-to-be-86-year-old’s extensive back catalogue. While awaiting a library hold of her memoir, Book of Lives, I’ve also been rereading the 1983 short story collection Bluebeard’s Egg.

Celebrating its 20th anniversary this year is The Penelopiad, Atwood’s contribution to Canongate’s The Myths series, from which I’ve also read the books by Karen Armstrong, A.S. Byatt, Ali Smith and Jeanette Winterson. I remember Armstrong’s basic point being that a myth is not a falsehood, as in common parlance, but a story that is always true even if not literally factual. Think of it as ‘these things happen’ rather than this happened. Greek mythology is every bit as brutal as the Hebrew Bible, and I find it instructive to interpret biblical stories the same way: Focus on timelessness and universality rather than on historicity.

I do the scheduling for my book club, so I cheekily set The Penelopiad as our November book so that it would count towards two blog challenges. Although it’s a feminist retelling of Homer’s The Odyssey, we concluded that it’s not essential to have prior knowledge of the Greek myths. Much of the narrative is from Penelope’s perspective, including from the afterlife. Cliché has it that she waited patiently for 20 years for her husband Odysseus to return from war, chastely warding off all her would-be suitors. But she admits to readers that both she and Odysseus are inveterate liars.

When Odysseus returned, he murdered the suitors and then Penelope’s maids – some of whom had consensual relations with the men; others of whom were raped. The focus is not on the slaughtered suitors, or on Odysseus’s triumphant return and revenge, but on the dozen maids – viz. the chapter title “Odysseus and Telemachus Snuff the Maids.” The murdered maids form a first-person plural voice (a literal Greek chorus) and speak in poetry and song, also commenting on their own plight through an anthropology lecture and a videotaped trial. They appeal to The Furies for posthumous justice, knowing they won’t get it from men (see the Virago anthology Furies). This sarcastic passage spotlights women’s suffering:

Never mind. Point being that you don’t have to get too worked up about us, dear educated minds. You don’t have to think of us as real girls, real flesh and blood, real pain, real injustice. That might be too upsetting. Just discard the sordid part. Consider us pure symbol. We’re no more real than money.

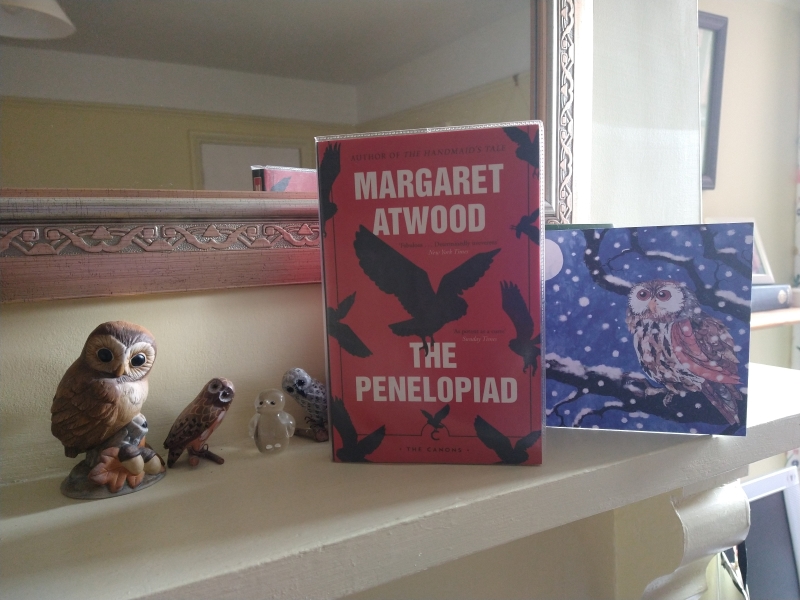

The cover of The Canons edition hints at the maids’ final transformation into legend.

As well as The Odyssey, Atwood drew on external sources. She considers the theory that Penelope was the leader of a goddess cult. Women are certainly the most interesting characters here. Penelope’s jealousy of her cousin Helen (of Troy) and her rocky relationship with her teenage son Telemachus are additional threads. Eurycleia, Odysseus’s nurse, is a minor character, and there is mention of Penelope’s mother, a Naiad. Odysseus himself comes across not as the brave hero but as brash, selfish and somewhat absurd.

As well as The Odyssey, Atwood drew on external sources. She considers the theory that Penelope was the leader of a goddess cult. Women are certainly the most interesting characters here. Penelope’s jealousy of her cousin Helen (of Troy) and her rocky relationship with her teenage son Telemachus are additional threads. Eurycleia, Odysseus’s nurse, is a minor character, and there is mention of Penelope’s mother, a Naiad. Odysseus himself comes across not as the brave hero but as brash, selfish and somewhat absurd.

Like Atwood’s other work, then, The Penelopiad is subversive and playful. We wondered whether it set the trend for Greek myth retellings – given that those by Pat Barker, Natalie Haynes, Madeline Miller, Jennifer Saint and more emerged 5–15 years later. It wouldn’t be a surprise: she has always been wise and ahead of her time, a puckish prophetess. This fierce, funny novella isn’t among my favourites of the 30 Atwood titles I’ve now read, but it was an offbeat selection that made for a good book club discussion – and it wouldn’t be the worst introduction to her feminist viewpoint.

(Public library)

[198 pages]

![]()

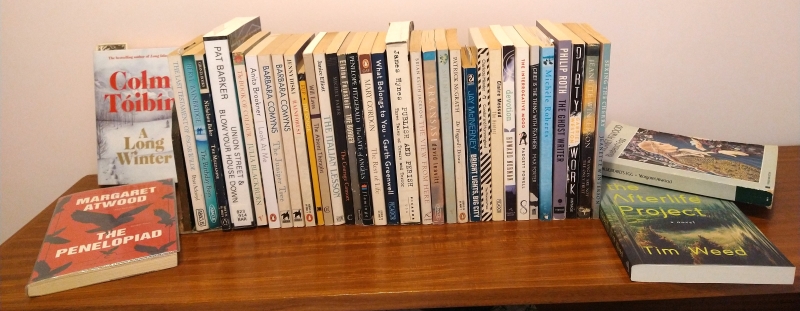

#NovNov25 and Other November Reading Plans

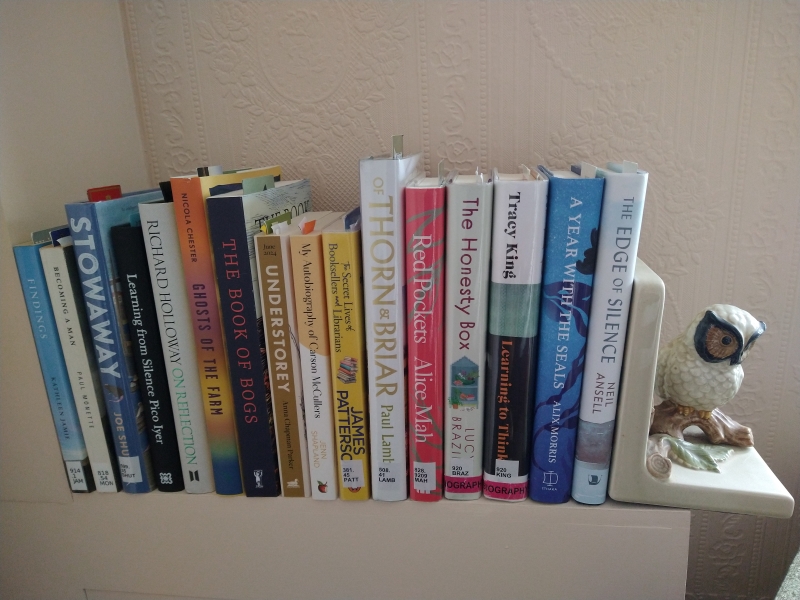

Not much more than two weeks now before Novellas in November (#NovNov25) begins! Cathy and I are getting geared up and making plans for what we’re going to read. I have a handful of novellas out from the library, but mostly I gathered potential reads from my own shelves. I’m hoping to coincide with several of November’s other challenges, too.

Although we’re not using the below as themes this year, I’ve grouped my options into categories:

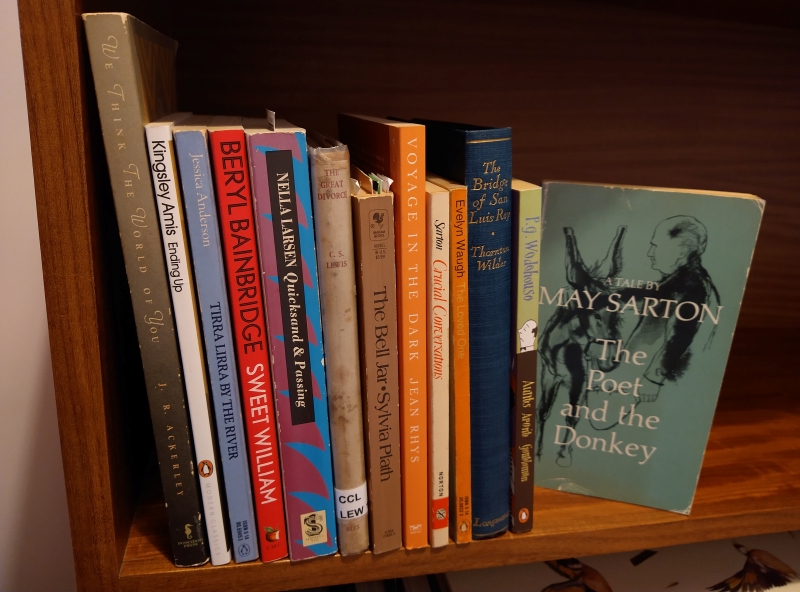

Short Classics (pre-1980)

Just Quicksand to read from the Larsen volume; the Wilder would be a reread.

Contemporary Novellas

(Just Blow Your House Down; and the last two of the three novellas in the Hynes.)

Also, on my e-readers: Sea, Poison by Caren Beilin, Likeness by Samsun Knight, Eradication: A Fable by Jonathan Miles (a 2026 release, to review early for Shelf Awareness)

*Margaret Atwood Reading Month is hosted by Marcie of Buried in Print. I’ve just read The Penelopiad for book club, so I’ll start off with a review of that. I might also reread Bluebeard’s Egg, and I’ll be eagerly awaiting her memoir from the library.

*Margaret Atwood Reading Month is hosted by Marcie of Buried in Print. I’ve just read The Penelopiad for book club, so I’ll start off with a review of that. I might also reread Bluebeard’s Egg, and I’ll be eagerly awaiting her memoir from the library.

[*Science Fiction Month: Beautyland by Marie-Helene Bertino, Archive of Unknown Universes by Ruben Reyes Jr., and The Afterlife Project (all catch-up review books) are options, plus I recently started reading The Martian by Andy Weir.]

Short Nonfiction

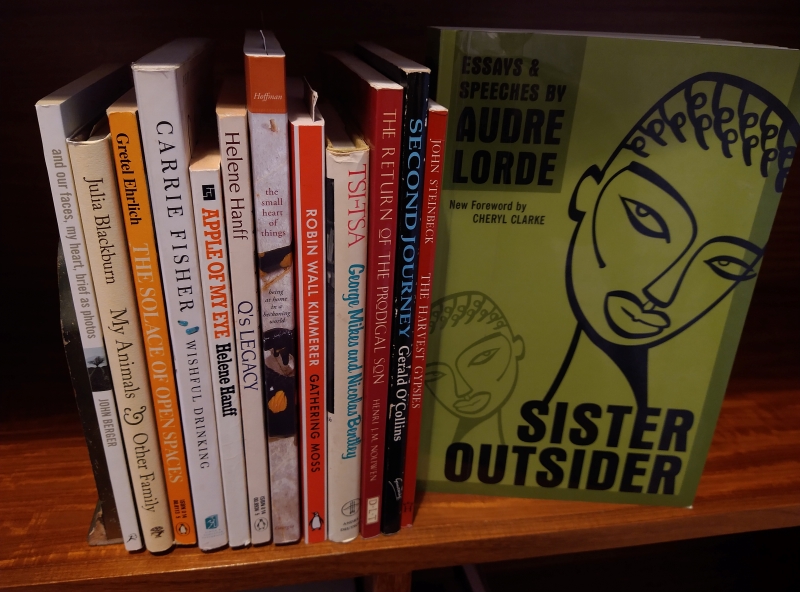

Including our buddy read, Sister Outsider by Audre Lorde. (A shame about that cover!)

Also, on my e-readers: The Serviceberry by Robin Wall Kimmerer, No Straight Road Takes You There by Rebecca Solnit, Because We Must by Tracy Youngblom. And, even though it doesn’t come out until February, I started reading The Irish Goodbye: Micro-Memoirs by Beth Ann Fennelly via Edelweiss.

For Nonfiction November, I also have plenty of longer nonfiction on the go, a mixture of review books to catch up on and books from the library:

I also have one nonfiction November release, Joyride by Susan Orlean, to review.

Novellas in Translation

At left are all the novella-length options, with four German books on top.

The Chevillard and Modiano are review copies to catch up on.

Also on the stack, from the library: Super-Frog Saves Tokyo by Haruki Murakami

On my e-readers: The Old Fire by Elisa Shua Dusapin, The Old Man by the Sea by Domenico Starnone, Our Precious Wars by Perrine Tripier

*German Literature Month: Our recent trip to Berlin and Lübeck whetted my appetite to read more German/German-language fiction. I’ll try to coincide with the Thomas Mann week as I was already planning to reread Death in Venice. I have some longer German books on the right-hand side as well. I started Kairos but found it hard going so might switch to audiobook. I also have Demian by Hermann Hesse on my Nook, downloaded from Project Gutenberg.

*German Literature Month: Our recent trip to Berlin and Lübeck whetted my appetite to read more German/German-language fiction. I’ll try to coincide with the Thomas Mann week as I was already planning to reread Death in Venice. I have some longer German books on the right-hand side as well. I started Kairos but found it hard going so might switch to audiobook. I also have Demian by Hermann Hesse on my Nook, downloaded from Project Gutenberg.

Spy any favourites or a particularly appealing title in my piles?

The link-up is now open for you to share your planning post!

Any novellas lined up to read next month?

#MARM2024: Life before Man and Interlunar by Margaret Atwood

Hard to believe, but it’s my seventh year participating in the annual Margaret Atwood Reading Month (#MARM) hosted by indomitable Canadian blogger Marcie of Buried in Print. In previous years, I’ve read Surfacing and The Edible Woman, The Robber Bride and Moral Disorder, Wilderness Tips, The Door, and Bodily Harm and Stone Mattress; and reread The Blind Assassin. I’m wishing a happy belated birthday to Atwood, who turned 85 earlier this month. Novembers are my excuse to catch up on her extensive back catalogue. In recent years, I’ve scoured the university library holdings to find works by her that I often had never heard of, as was the case with this early novel and mid-career poetry collection.

Life before Man (1979)

Atwood’s fourth novel is from three rotating third-person POVs: Toronto museum curator Elizabeth, her toy-making husband Nate, and Lesje (pronounced “Lashia,” according to a note at the front), Elizabeth’s paleontologist colleague. The dated chapters span nearly two years, October 1976 to August 1978; often we visit with two or three protagonists on the same day. Elizabeth and Nate, parents to two daughters, have each had a string of lovers. Elizabeth’s most recent, Chris, has died by suicide. Nate disposes of his latest mistress, Martha, and replaces her with Lesje, who is initially confused by his interest in her. She’s more attracted to rocks and dinosaurs than to people, in a way that could be interpreted as consistent with neurodivergence.

Atwood’s fourth novel is from three rotating third-person POVs: Toronto museum curator Elizabeth, her toy-making husband Nate, and Lesje (pronounced “Lashia,” according to a note at the front), Elizabeth’s paleontologist colleague. The dated chapters span nearly two years, October 1976 to August 1978; often we visit with two or three protagonists on the same day. Elizabeth and Nate, parents to two daughters, have each had a string of lovers. Elizabeth’s most recent, Chris, has died by suicide. Nate disposes of his latest mistress, Martha, and replaces her with Lesje, who is initially confused by his interest in her. She’s more attracted to rocks and dinosaurs than to people, in a way that could be interpreted as consistent with neurodivergence.

It was neat to follow along seasonally with Halloween and Remembrance Day and so on, and see the Quebec independence movement simmering away in the background. To start with, I was engrossed in the characters’ perspectives and taken with Atwood’s witty descriptions and dialogue: “[Nate]’s heard Unitarianism called a featherbed for falling Christians” and (Lesje:) “Elizabeth needs support like a nun needs tits.” My favourite passage encapsulates a previous relationship of Lesje’s perfectly, in just the sort of no-nonsense language she would use:

The geologist had been fine; they could compromise on rock strata. They went on hikes with their little picks and kits, and chipped samples off cliffs; then they ate jelly sandwiches and copulated in a friendly way behind clumps of goldenrod and thistles. She found this pleasurable but not extremely so. She still has a collection of rock chips left over from this relationship; looking at it does not fill her with bitterness. He was a nice boy but she wasn’t in love with him.

Elizabeth’s formidable Auntie Muriel is a terrific secondary presence. But this really is just a novel about (repeated) adultery and its aftermath. The first line has Elizabeth thinking “I don’t know how I should live,” and after some complications, all three characters are trapped in a similar stasis by the end. By the halfway point I’d mostly lost interest and started skimming. The grief motif and museum setting weren’t the draws I’d expected them to be. Lesje is a promising character but, disappointingly, gets snared in clichéd circumstances. No doubt that is part of the point; “life before man” would have been better for her. (University library) ![]()

This prophetic passage from Life before Man leads nicely into the themes of Interlunar:

The real question is: Does [Lesje] care whether the human race survives or not? She doesn’t know. The dinosaurs didn’t survive and it wasn’t the end of the world. In her bleaker moments, … she feels the human race has it coming. Nature will think up something else. Or not, as the case may be.

The posthuman prospect is echoed in Interlunar in the lines: “Which is the sound / the earth will make for itself / without us. A stone echoing a stone.”

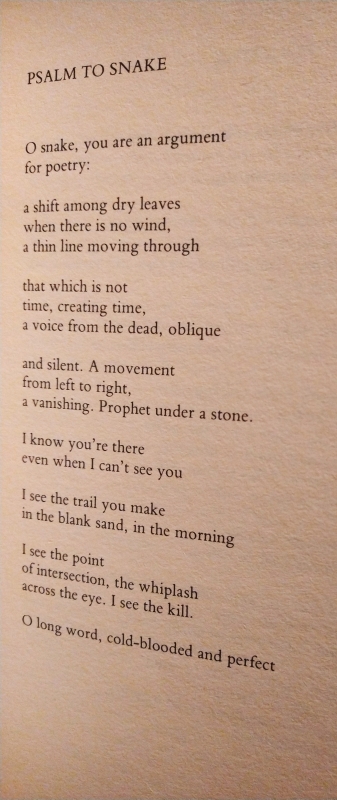

Interlunar (1984)

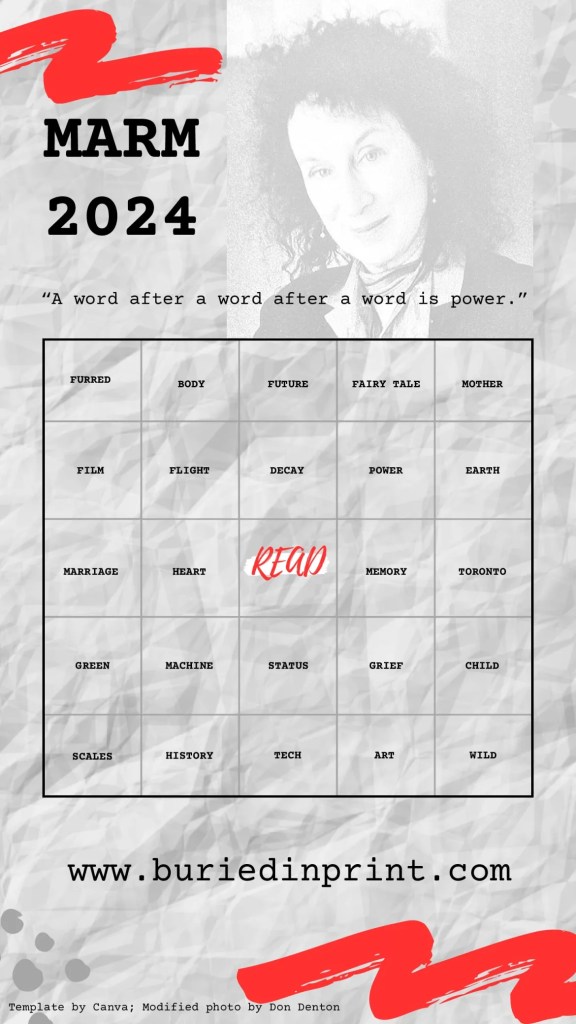

Some familiar Atwood elements in this volume, including death, mythology, nature, and stays at a lake house; you’ll even recognize a couple of her other works in poem titles “The Robber Bridegroom” and “The Burned House.” The opening set of “Snake Poems” got me the “green” and “scales” squares on Marcie’s Bingo card (in addition to various other scattered ones, I’m gonna say I’ve filled the whole right-hand column thanks to these two books).

This one brilliantly likens the creature to the sinuous ways of language:

“A Holiday” imagines a mother–daughter camping vacation presaging a postapocalyptic struggle for survival: “This could be where we / end up, learning the minimal / with maybe no tree, no rain, / no shelter, no roast carcasses / of animals to renew us … So far we do it / for fun.” As in her later collection The Door, portals and thresholds are of key importance. “Doorway” intones, “November is the month of entrance, / month of descent. Which has passed easily, / which has been lenient with me this year. / Nobody’s blood on the floor.” There are menace and melancholy here. But as “Orpheus (2)” suggests at its close, art can be an ongoing act of resistance: “To sing is either praise / or defiance. Praise is defiance.” I do recommend Atwood’s poetry if you haven’t tried it before, even if you’re not typically a poetry reader. Her poems are concrete and forceful, driven by imagery and voice; not as abstract as you might fear. Alas, I wasn’t sent a review copy of her collected poems, Paper Boat, as I’d hoped, but I will continue to enjoy encountering them piecemeal. (University library)

“A Holiday” imagines a mother–daughter camping vacation presaging a postapocalyptic struggle for survival: “This could be where we / end up, learning the minimal / with maybe no tree, no rain, / no shelter, no roast carcasses / of animals to renew us … So far we do it / for fun.” As in her later collection The Door, portals and thresholds are of key importance. “Doorway” intones, “November is the month of entrance, / month of descent. Which has passed easily, / which has been lenient with me this year. / Nobody’s blood on the floor.” There are menace and melancholy here. But as “Orpheus (2)” suggests at its close, art can be an ongoing act of resistance: “To sing is either praise / or defiance. Praise is defiance.” I do recommend Atwood’s poetry if you haven’t tried it before, even if you’re not typically a poetry reader. Her poems are concrete and forceful, driven by imagery and voice; not as abstract as you might fear. Alas, I wasn’t sent a review copy of her collected poems, Paper Boat, as I’d hoped, but I will continue to enjoy encountering them piecemeal. (University library) ![]()

Margaret Atwood Reading Month: The Door (#MARM)

It’s my fifth year participating in the annual Margaret Atwood Reading Month (#MARM), hosted by indomitable Canadian blogger Marcie of Buried in Print. In previous years for this challenge, I’ve read Surfacing and The Edible Woman, The Robber Bride and Moral Disorder, and Wilderness Tips; and reread The Blind Assassin. Today is Atwood’s 83rd birthday, so what better time to show her some love?

Like the Beatles, she’s worked in so many different genres and styles that I don’t see how anyone could say they don’t like her – you just haven’t explored her oeuvre deeply enough. Although she’s best known for her fiction, she started off as a poet, with a whole five collections published in the 1960s before her first novel appeared. I’d previously read her Eating Fire: Selected Poetry 1965–1995 and Dearly, my top poetry read of 2020.

The Door (2007) was at that point her first poetry release in 12 years and features a number of the same themes that permeate her novels and nonfiction: memory, writing, ageing, travel and politics. I particularly like the early poems where she reinhabits memories of childhood and early adulthood, often through objects. Such artifacts are “pocketed as pure mementoes / of some once indelible day,” she writes in “Year of the Hen.”

The Door (2007) was at that point her first poetry release in 12 years and features a number of the same themes that permeate her novels and nonfiction: memory, writing, ageing, travel and politics. I particularly like the early poems where she reinhabits memories of childhood and early adulthood, often through objects. Such artifacts are “pocketed as pure mementoes / of some once indelible day,” she writes in “Year of the Hen.”

These are followed by a trilogy about the death of the family’s pet cat, Blackie. “We get too sentimental / over dead animals. / We turn maudlin,” she acknowledges in “Mourning for Cats,” yet “Blackie in Antarctica” injects some humour as she remembers how her sister kept the cat’s corpse in the freezer until she could come home to bury it. Also on the lighter side is a long “where are they now?” update for the Owl and the Pussycat.

There are also meta reflections on poetry, slightly menacing observations on the weather (an implacable, fate-like force) and the seasons (autumn = hunting), virtual visits to the Arctic, mild complaints about the elderly not being taken seriously, and thoughts on duty.

Four in a row muse about war – the Vietnam War in particular, I think? “The Last Rational Man” is a sinister standout, depicting a figure who is doomed under Caligula’s reign. Whoever she may have had in mind when she wrote this, it’s just as relevant 15 years later.

In the final, title poem, which appears to be modelled on the Seven Ages of Man, a door is a metaphor for life’s transitions and, ultimately, for death.

The door swings open:

O god of hinges,

god of long voyages,

you have kept faith.

It’s dark in there.

You confide yourself to the darkness.

You step in.

The door swings closed.

Apart from a few end rhymes, Atwood relies more on theme than on sonic technique or form. That, I think, makes her poetry accessible to those who are new to or suspicious of verse. Happy birthday, M.A., and thank you for your literary wisdom and innovation! (Little Free Library)

The Blind Assassin Reread for #MARM, and Other Doorstoppers

It’s the fourth annual Margaret Atwood Reading Month (#MARM), hosted by Canadian blogger extraordinaire Marcie of Buried in Print. In previous years, I’ve read Surfacing and The Edible Woman, The Robber Bride and Moral Disorder, and Wilderness Tips. This year Laila at Big Reading Life and I did a buddy reread of The Blind Assassin, which was historically my favourite Atwood novel. I’d picked up a free paperback the last time I was at The Book Thing of Baltimore. Below are some quick thoughts based on what I shared with Laila as I was reading.

The Blind Assassin (2000)

Winner of the Booker Prize and Hammett Prize; shortlisted for the Orange Prize

I must have first read this about 13 years ago. The only thing I remembered before I started my reread was that there is a science fiction book-within-the-book. I couldn’t recall anything else about the setup before I read in the blurb about the suspicious circumstances of Laura’s death in 1945. Indeed, the opening line, which deserves to be famous, is “Ten days after the war ended, my sister Laura drove a car off a bridge.”

I always love novels about sisters, and Iris is a terrific narrator. Now a cantankerous elderly woman, she takes us back through her family history: her father’s button factory and his clashes with organizing workers, her mother’s early death, and her enduring relationship with their housekeeper, Reenie. Iris and Laura met a young man named Alex Thomas, a war orphan with radical views, at the factory’s Labour Day picnic, and it was clear early on that Laura was smitten, while Iris went on to marry Richard Griffen, a nouveau riche industrialist.

Interspersed with Iris’s recollections are newspaper articles that give a sense that the Chase family might be cursed, and excerpts from The Blind Assassin, Laura’s posthumously published novel. Daring for its time in terms of both explicit content and literary form (e.g., no speech marks), it has a storyline rather similar to 1984, with an upper-crust woman having trysts with a working-class man in his squalid lodgings. During their time snatched together, he also tells her a story inspired by the pulp sci-fi of the time. I was less engaged by the story-within-the-story(-within-the-story) this time around compared to Iris’s current life and flashbacks.

In the back of my mind, I had a vague notion that there was a twist coming, and in my impatience to see if I was right I ended up skimming much of the second half of the novel. My hunch was proven correct, but I was disappointed with myself that I wasn’t able to enjoy the journey more a second time around. Overall, this didn’t wow me on a reread, but then again, I am less dazzled by literary “tricks” these days. At the sentence level, however, the writing was fantastic, including descriptions of places, seasons and characters’ psychology. It’s intriguing to think about whether we can ever truly know Laura given Iris’s guardianship of her literary legacy.

If you haven’t read this before, find a time when you can give it your full attention and sink right in. It’s so wise on family secrets and the workings of memory and celebrity, and the weaving in of storylines in preparation for the big reveal is masterful.

Some favourite passages:

“What fabrications they are, mothers. Scarecrows, wax dolls for us to stick pins into, crude diagrams. We deny them an existence of their own, we make them up to suit ourselves – our own hungers, our own wishes, our own deficiencies.”

“Beginnings are sudden, but also insidious. They creep up on you sideways, they keep to the shadows, they lurk unrecognized. Then, later, they spring.”

“The only way you can write the truth is to assume that what you set down will never be read. Not by any other person, and not even by yourself at some later date. Otherwise you begin excusing yourself. You must see the writing as emerging like a long scroll of ink from the index finger of your right hand; you must see your left hand erasing it. Impossible, of course.”

My original rating (c. 2008):

My rating now:

What to read for #MARM next year, I wonder??

In general, I have been struggling mightily with doorstoppers this year. I just don’t seem to have the necessary concentration, so Novellas in November has been a boon. I’ve been battling with Ruth Ozeki’s latest novel for months, and another attempted buddy read of 460 pages has also gone by the wayside. I’ll write a bit more on this for #LoveYourLibrary on Monday, including a couple of recent DNFs. The Blind Assassin was only my third successful doorstopper of the year so far. After The Absolute Book, the other one was:

The Lincoln Highway by Amor Towles

In Towles’ third novel – a big, old-fashioned dose of Americana – brothers and pals set out from Nebraska on road and rail adventures to find a fortune in 1950s New York. The book features some fantastic characters. Precocious Billy steals every scene he appears in. Duchess is a delightfully flamboyant bounder, peppering his speech with malapropisms and Shakespeare quotes. However, Emmett is a dull protagonist, and it’s disappointing that Sally, one of just two main female characters, plays such a minor role. A danger with an episodic narrative is that random events and encounters pile up but don’t do much to further the plot. At nearly 200 pages in, I realized little of consequence had happened yet. A long road, then, with some ups and downs along the way, but Towles’ fans will certainly want to sign up for the ride.

In Towles’ third novel – a big, old-fashioned dose of Americana – brothers and pals set out from Nebraska on road and rail adventures to find a fortune in 1950s New York. The book features some fantastic characters. Precocious Billy steals every scene he appears in. Duchess is a delightfully flamboyant bounder, peppering his speech with malapropisms and Shakespeare quotes. However, Emmett is a dull protagonist, and it’s disappointing that Sally, one of just two main female characters, plays such a minor role. A danger with an episodic narrative is that random events and encounters pile up but don’t do much to further the plot. At nearly 200 pages in, I realized little of consequence had happened yet. A long road, then, with some ups and downs along the way, but Towles’ fans will certainly want to sign up for the ride.

See my full review for BookBrowse; see also my related article on Studebaker cars.

With thanks to Hutchinson for the free copy for review.

My hold on Margaret Atwood’s memoir, Book of Lives, arrived in late November. It’ll be my first read for Doorstoppers in December. I’d also been casually rereading her 1983 short story collection Bluebeard’s Egg and managed the first two stories; I’ll return to the rest next year. A recent

My hold on Margaret Atwood’s memoir, Book of Lives, arrived in late November. It’ll be my first read for Doorstoppers in December. I’d also been casually rereading her 1983 short story collection Bluebeard’s Egg and managed the first two stories; I’ll return to the rest next year. A recent  Bluebeard’s Egg opens with two Alice Munro-esque stories, “Significant Moments in the Life of My Mother” and “Hurricane Hazel,” both of which track with facts revealed in the memoir. The former draws on her mother Margaret’s Nova Scotia upbringing as the daughter of a country doctor (to avoid confusion, Atwood was nicknamed “Peggy”). Out of a welter of random stories comes the universal paradox: that she is in some ways exactly like her mother, and in others couldn’t be more different. It closes: “I had become a visitant from outer space, a time-traveller come back from the future, bearing news of a great disaster.” The latter story features a young teenage girl in a half-hearted relationship with an older, cooler boyfriend, mostly because she thinks it’s what’s expected of her. Atwood addresses it explicitly:

Bluebeard’s Egg opens with two Alice Munro-esque stories, “Significant Moments in the Life of My Mother” and “Hurricane Hazel,” both of which track with facts revealed in the memoir. The former draws on her mother Margaret’s Nova Scotia upbringing as the daughter of a country doctor (to avoid confusion, Atwood was nicknamed “Peggy”). Out of a welter of random stories comes the universal paradox: that she is in some ways exactly like her mother, and in others couldn’t be more different. It closes: “I had become a visitant from outer space, a time-traveller come back from the future, bearing news of a great disaster.” The latter story features a young teenage girl in a half-hearted relationship with an older, cooler boyfriend, mostly because she thinks it’s what’s expected of her. Atwood addresses it explicitly: One can also trace The Penelopiad (see my

One can also trace The Penelopiad (see my

I had literally never heard of her fifth novel before I spotted it on the library catalogue and decided to have a go. The fact that nobody talks about it is evidence, I think, of an overbaked plot and more successful treatment of her trademark themes in other books. Nonetheless, it was perfectly readable and had its highlights. Renata Wilford, “Rennie,” is a journalist for hire from Ontario who has recently had her life turned upside down by breast cancer and the departure of her boyfriend, Jake. She flies to the Caribbean island nation of St. Antoine to write a travel piece, coinciding with the first elections since the British left. It’s a febrile postcolonial setting of shantytowns and shortages. Rennie tries to focus on boat trips, cocktails and beach lounging, but Dr. Minnow, who she met on the plane, is determined to show her the reality of his country – cold truths that include assassination and imprisonment.

I had literally never heard of her fifth novel before I spotted it on the library catalogue and decided to have a go. The fact that nobody talks about it is evidence, I think, of an overbaked plot and more successful treatment of her trademark themes in other books. Nonetheless, it was perfectly readable and had its highlights. Renata Wilford, “Rennie,” is a journalist for hire from Ontario who has recently had her life turned upside down by breast cancer and the departure of her boyfriend, Jake. She flies to the Caribbean island nation of St. Antoine to write a travel piece, coinciding with the first elections since the British left. It’s a febrile postcolonial setting of shantytowns and shortages. Rennie tries to focus on boat trips, cocktails and beach lounging, but Dr. Minnow, who she met on the plane, is determined to show her the reality of his country – cold truths that include assassination and imprisonment.

Nonetheless, I found it frustrating that it took so long to get through a story/disc, surely longer than I would have spent reading with my eyes (and so I have only managed 7.5 of 9 stories so far), and it was slightly harder for me to concentrate. It was also disorienting to not have visual cues, such that I had no idea how much of a story was remaining, and sometimes didn’t know how place or character names were spelt. One interesting novelty, though, was the reader voices. There are five different voice actors on this audiobook, three women (including MA herself on the title story) and two men. It is interesting to ponder how their intonation might affect my reaction to a story. For instance, Rob Delaney’s deadpan delivery really makes “The Freeze-Dried Groom,” a witty work of mild horror in which a fraudulent antiques dealer finds an entire wedding, complete with groom, abandoned in a storage unit.

Nonetheless, I found it frustrating that it took so long to get through a story/disc, surely longer than I would have spent reading with my eyes (and so I have only managed 7.5 of 9 stories so far), and it was slightly harder for me to concentrate. It was also disorienting to not have visual cues, such that I had no idea how much of a story was remaining, and sometimes didn’t know how place or character names were spelt. One interesting novelty, though, was the reader voices. There are five different voice actors on this audiobook, three women (including MA herself on the title story) and two men. It is interesting to ponder how their intonation might affect my reaction to a story. For instance, Rob Delaney’s deadpan delivery really makes “The Freeze-Dried Groom,” a witty work of mild horror in which a fraudulent antiques dealer finds an entire wedding, complete with groom, abandoned in a storage unit.

If pressed to give a one-line summary, I would say the overall theme of this collection is the power that women have (or do not have) in relationships – this is often a question of sex, but not always. Much of the collection falls neatly into pairs: “True Trash” and “Death by Landscape” are about summer camp and the effects that experiences had there still have decades later; “The Bog Man” and “The Age of Lead” both use the discovery of a preserved corpse (one a bog body, the other a member of the Franklin Expedition) as a metaphor for a frozen relationship; and “Hairball” and “Weight” are about a mistress’s power plays. I actually made myself a key on the table of contents page, assigning A, B, and C to those topics. The title story I labeled [A/C] because it’s set at a family’s lake house but the foreign spouse of one of the sisters has history with or designs on all three.

If pressed to give a one-line summary, I would say the overall theme of this collection is the power that women have (or do not have) in relationships – this is often a question of sex, but not always. Much of the collection falls neatly into pairs: “True Trash” and “Death by Landscape” are about summer camp and the effects that experiences had there still have decades later; “The Bog Man” and “The Age of Lead” both use the discovery of a preserved corpse (one a bog body, the other a member of the Franklin Expedition) as a metaphor for a frozen relationship; and “Hairball” and “Weight” are about a mistress’s power plays. I actually made myself a key on the table of contents page, assigning A, B, and C to those topics. The title story I labeled [A/C] because it’s set at a family’s lake house but the foreign spouse of one of the sisters has history with or designs on all three.

To open the afternoon program, Dr. Fiona Tolan of Liverpool John Moores University spoke on “21st-century Gileads: Feminist Dystopian Fiction after Atwood.” She noted that The Handmaid’s Tale casts a long shadow; it’s entered into our cultural lexicon and isn’t going anywhere. She showed covers of three fairly recent books that take up the Handmaid’s red: The Power, Vox, and Red Clocks. However, the two novels she chose to focus on do not have comparable covers: The Water Cure by Sophie Mackintosh (

To open the afternoon program, Dr. Fiona Tolan of Liverpool John Moores University spoke on “21st-century Gileads: Feminist Dystopian Fiction after Atwood.” She noted that The Handmaid’s Tale casts a long shadow; it’s entered into our cultural lexicon and isn’t going anywhere. She showed covers of three fairly recent books that take up the Handmaid’s red: The Power, Vox, and Red Clocks. However, the two novels she chose to focus on do not have comparable covers: The Water Cure by Sophie Mackintosh ( Zenia is dead, to begin with. Or is she? Five years after her funeral, as Tony, Roz and Charis, the university frenemies from whom she stole lovers and money, are eating lunch at The Toxique, Zenia comes back. Much of the book delves into the Toronto set’s history, with Tony seeming to get the most space and sympathy – she’s a lot like Nell (see below), so probably the most autobiographical character here, and the one I warmed to the most. Tony’s mother left and her father committed suicide, so she’s always been an unusual loner with a rich inner life, speaking and writing backwards (like Adah in

Zenia is dead, to begin with. Or is she? Five years after her funeral, as Tony, Roz and Charis, the university frenemies from whom she stole lovers and money, are eating lunch at The Toxique, Zenia comes back. Much of the book delves into the Toronto set’s history, with Tony seeming to get the most space and sympathy – she’s a lot like Nell (see below), so probably the most autobiographical character here, and the one I warmed to the most. Tony’s mother left and her father committed suicide, so she’s always been an unusual loner with a rich inner life, speaking and writing backwards (like Adah in  The title came from Atwood’s late partner, Graeme Gibson, who stopped writing novels in 1996 and gave her permission to reuse the name of his work in progress. It suggests that all is not quite as it should be. Then again, morality is subjective. Though her parents disapprove of Nell setting up a household with Tig, who is still married to Oona, the mother of his children, theirs ends up being a stable and traditional relationship; nothing salacious about it.

The title came from Atwood’s late partner, Graeme Gibson, who stopped writing novels in 1996 and gave her permission to reuse the name of his work in progress. It suggests that all is not quite as it should be. Then again, morality is subjective. Though her parents disapprove of Nell setting up a household with Tig, who is still married to Oona, the mother of his children, theirs ends up being a stable and traditional relationship; nothing salacious about it.