Recent Literary Awards & Online Events: Folio Prize and Claire Fuller

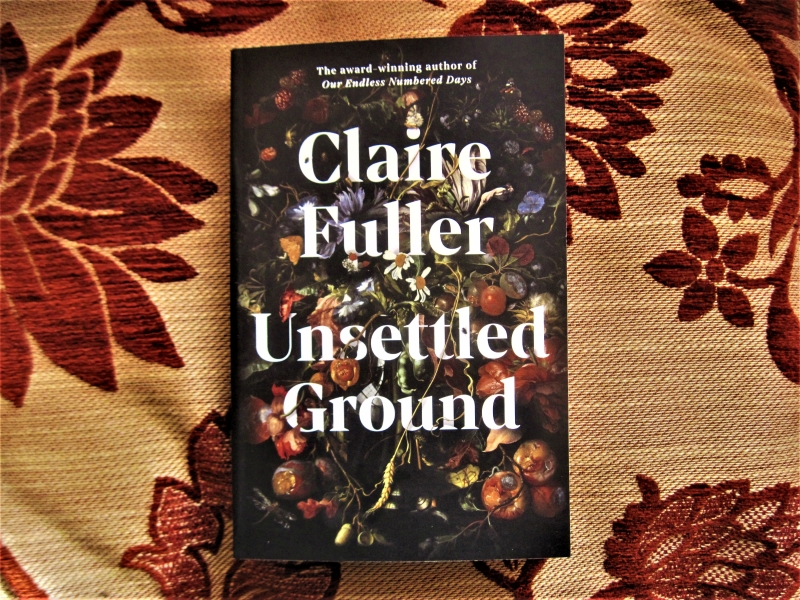

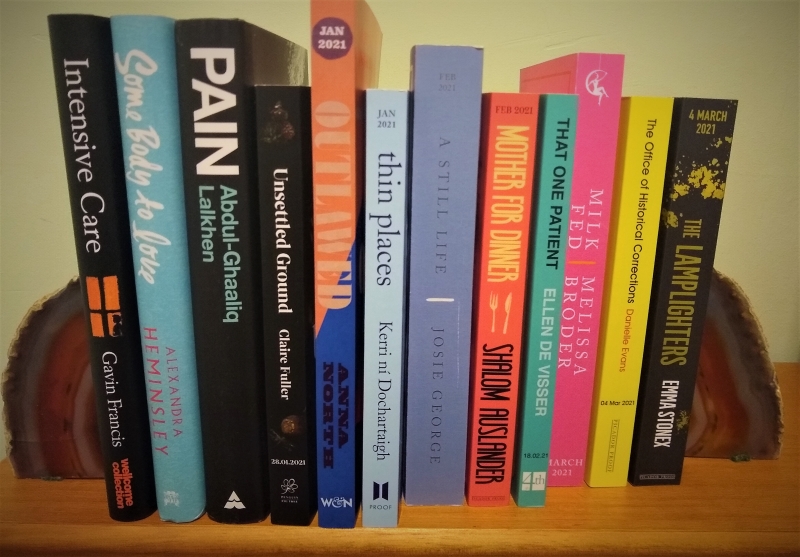

Literary prize season is in full swing! The Women’s Prize longlist, revealed on the 10th, contained its usual mixture of the predictable and the unexpected. I correctly predicted six of the nominees, and happened to have already read seven of them, including Claire Fuller’s Unsettled Ground (more on this below). I’m currently reading another from the longlist, Luster by Raven Leilani, and I have four on order from the library. There are only four that I don’t plan to read, so I’ll be in a fairly good place to predict the shortlist (due out on April 28th). Laura and Rachel wrote detailed reaction posts on which there has been much chat.

Rathbones Folio Prize

This year I read almost the entire Rathbones Folio Prize shortlist because I was lucky enough to be sent the whole list to feature on my blog. The winner, which the Rathbones CEO said would stand as the “best work of literature for the year” out of 80 nominees, was announced on Wednesday in a very nicely put together half-hour online ceremony hosted by Razia Iqbal from the British Library. The Folio scheme also supports writers at all stages of their careers via a mentorship scheme.

It was fun to listen in as the three judges discussed their experience. “Now nonfiction to me seems like rock ‘n’ roll,” Roger Robinson said, “far more innovative than fiction and poetry.” (Though Sinéad Gleeson and Jon McGregor then stood up for the poetry and fiction, respectively.) But I think that was my first clue that the night was going to go as I’d hoped. McGregor spoke of the delight of getting “to read above the categories, looking for freshness, for excitement.” Gleeson said that in the end they had to choose “the book that moved us, that enthralled us.”

All eight authors had recorded short interview clips about their experience of lockdown and how they experiment with genre and form, and seven (all but Doireann Ní Ghríofa) were on screen for the live announcement. The winner of the £30,000 prize, author of an “exceptional, important” book and teller of “a story that had to be told,” was Carmen Maria Machado for In the Dream House. I was delighted with this result: it was my first choice and is one of the most remarkable memoirs I’ve read. I remember reading it on my Kindle on the way to and from Hungerford for a bookshop event in early March 2020 – my last live event and last train ride in over a year and counting, which only made the reading experience more memorable.

I like what McGregor had to say about the book in the media release: “In the Dream House has changed me – expanded me – as a reader and a person, and I’m not sure how much more we can ask of the books that we choose to celebrate.”

There are now only two previous Folio winners that I haven’t read, the memoir The Return by Hisham Matar and the novel Lost Children Archive by Valeria Luiselli, so I’d like to get those two out from the library soon and complete the set.

Other literary prizes

The following day, the Dylan Thomas Prize shortlist was announced. Still in the running are two novels I’ve read and enjoyed, Pew by Catherine Lacey and My Dark Vanessa by Kate Elizabeth Russell, and one I’m currently reading (Luster). Of the rest, I’m particularly keen on Kingdomtide by Rye Curtis, and I would also like to read Alligator and Other Stories by Dima Alzayat. I’d love to see Russell win the whole thing. The announcement will be on May 13th. I hope to participate in a shortlist blog tour leading up to it.

The following day, the Dylan Thomas Prize shortlist was announced. Still in the running are two novels I’ve read and enjoyed, Pew by Catherine Lacey and My Dark Vanessa by Kate Elizabeth Russell, and one I’m currently reading (Luster). Of the rest, I’m particularly keen on Kingdomtide by Rye Curtis, and I would also like to read Alligator and Other Stories by Dima Alzayat. I’d love to see Russell win the whole thing. The announcement will be on May 13th. I hope to participate in a shortlist blog tour leading up to it.

I also tuned into the Edward Stanford Travel Writing Awards ceremony (on YouTube), which was unfortunately marred by sound issues. This year’s three awards went to women: Dervla Murphy (Edward Stanford Outstanding Contribution to Travel Writing), Anita King (Bradt Travel Guides New Travel Writer of the Year; you can read her personal piece on Syria here), and Taran N. Khan for Shadow City: A Woman Walks Kabul (Stanford Dolman Travel Book of the Year in association with the Authors’ Club).

Other prize races currently in progress that are worth keeping an eye on:

- The Jhalak Prize for writers of colour in Britain (I’ve read four from the longlist and would be interested in several others if I could get hold of them)

- The Republic of Consciousness Prize for work from small presses (I’ve read two; Doireann Ní Ghríofa gets another chance – fingers crossed for her)

- The Walter Scott Prize for historical fiction (next up for me: The Dictionary of Lost Words by Pip Williams, to review for BookBrowse)

Claire Fuller

Yesterday evening, I attended the digital book launch for Claire Fuller’s Unsettled Ground (my review will be coming soon). I’ve read all four of her novels and count her among my favorite contemporary writers. I spotted Eric Anderson and Ella Berthoud among the 200+ attendees, and Claire’s agent quoted from Susan’s review – “A new novel from Fuller is always something to celebrate”! Claire read a passage from the start of the novel that introduces the characters just as Dot starts to feel unwell. Uniquely for online events I’ve attended, we got a tour of the author’s writing room, with Alan the (female) cat asleep on the daybed behind her, and her librarian husband Tim helped keep an eye on the chat.

After each novel, as a treat to self, she buys a piece of art. This time, she commissioned a ceramic plate from Sophie Wilson with lines and images from the book painted on it. Live music was provided by her son Henry Ayling, who played acoustic guitar and sang “We Roamed through the Garden,” which, along with traditional folk song “Polly Vaughn,” are quoted in the novel and were Claire’s earworms for two years. There was also a competition to win a chocolate Easter egg, given to whoever came closest to guessing the length of the new novel in words. (It was somewhere around 89,000.)

Good news – she’s over halfway through Book 5!

Recent Online Events: Melanie Finn, Church Times Festival, Gavin Francis

It’s coming up on the one-year anniversary of the first UK lockdown and here we are still living our lives online. The first hint I had of how serious things were going to get was when a London event with Anne Tyler I was due to attend in March 2020 with Eric and Laura T. was cancelled, followed by … everything else. Oh well.

This February was a bountiful month for online literary conversations. I’m catching up now by writing up my notes from a few more events (after Saunders and Ishiguro) that helped to brighten my evenings and weekends.

Melanie Finn in Conversation with Claire Fuller

(Exile in Bookville American online bookstore event on Facebook, February 2nd)

I was a big fan of Melanie Finn’s 2015 novel Shame (retitled The Gloaming), which I reviewed for Third Way magazine. Her new book, The Hare, sounds appealing but isn’t yet available in the UK. Rosie and Bennett, a 20-years-older man, meet in New York City. Readers soon enough know that he is a scoundrel, but Rosie doesn’t, and they settle together in Vermont. A contemporary storyline looking back at how they met contrasts the romantic potential of their relationship with its current reality.

Fuller said The Hare is her favorite kind of novel: literary but also a page-turner. (Indeed, the same could be said of Fuller’s books.) She noted that Finn’s previous three novels are all partly set in Africa and have a seam of violence – perhaps justified – running through. Finn acknowledged that everyday life in a postcolonial country has been a recurring element in her fiction, arising from her own experience growing up in Kenya, but the new book marked a change of heart: there is so much coming out of Africa by Black writers that she feels she doesn’t have anything to add. The authors agreed you have to be cruel to your characters.

Fuller said The Hare is her favorite kind of novel: literary but also a page-turner. (Indeed, the same could be said of Fuller’s books.) She noted that Finn’s previous three novels are all partly set in Africa and have a seam of violence – perhaps justified – running through. Finn acknowledged that everyday life in a postcolonial country has been a recurring element in her fiction, arising from her own experience growing up in Kenya, but the new book marked a change of heart: there is so much coming out of Africa by Black writers that she feels she doesn’t have anything to add. The authors agreed you have to be cruel to your characters.

Finn believes descriptive writing is one of her strengths, perhaps due to her time as a journalist. She still takes inspiration from headlines. Now that she and her family (a wildlife filmmaker husband and twin daughters born in her forties) are rooted in Vermont, she sees more nature writing in her work. They recovered a clear-cut plot and grow their own food; they also forage in the woods, and a hunter shoots surplus deer and gives them the venison. Appropriately, she read a tense deer-hunting passage from The Hare. Finn also teaches skiing and offers much the same advice as about writing: repetition eventually leads to elegance.

I was especially interested to hear the two novelists compare their composition process. Finn races through a draft in two months, but rewriting takes her a year, and she always knows the ending in advance. Fuller’s work, on the other hand, is largely unplanned; she starts with a character and a place and then just writes, finding out what she’s created much later on. (If you’ve read her Women’s Prize-longlisted upcoming novel, Unsettled Ground, you, too, would have noted her mention of a derelict caravan in the woods that her son took her to see.) Both said they don’t really like writing! Finn said she likes the idea of being a writer, while Fuller that she likes having written – a direct echo of Dorothy Parker’s quip: “I hate writing. I love having written.” Their fiction makes a good pairing and the conversation flowed freely.

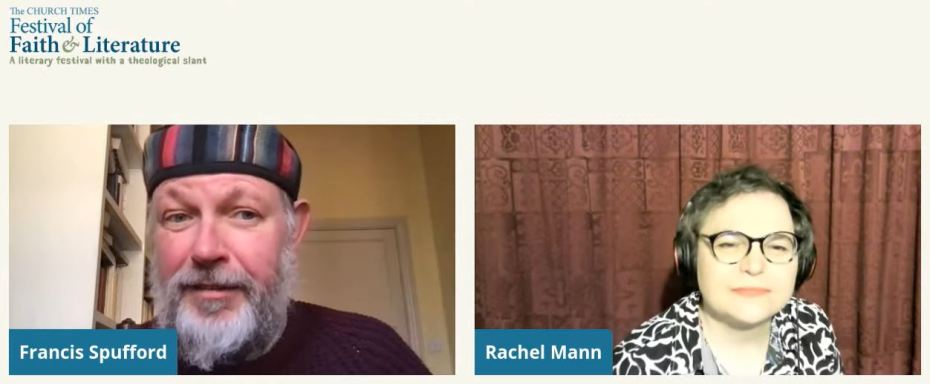

Church Times Festival of Faith and Literature, “Light in Darkness,” Part I

(February 20th)

I’d attended once in person, in 2016 (see my write-up of Sarah Perry and more), when this was still known as Bloxham Festival and was held at Bloxham School in Oxfordshire. Starting next year, it will take place in central Oxford instead. I attended the three morning events of Part I; there’s another virtual program taking place on Saturday the 17th of April.

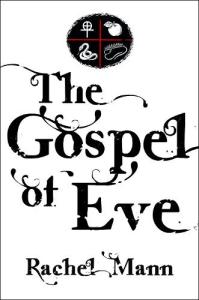

Rachel Mann on The Gospel of Eve

Mann opened with a long reading from Chapter 1 of her debut novel (I reviewed it here) and said it is about her “three favorite things: sex, death, and religion,” all of which involve a sort of self-emptying. Mark Oakley, dean of St John’s College, Cambridge, interviewed her. He noted that her book has been likened to “Dan Brown on steroids.” Mann laughed but recognizes that, though she’s a ‘serious poet’, her gift as a novelist is for pace. She’s a lover of thrillers and, like Brown, gets obsessed with secrets. Although she and her protagonist, Kitty, are outwardly similar (a rural, working-class background and theological training), she quoted Evelyn Waugh’s dictum that all characters should be based on at least three people. Mann argued that the Church has not dealt as well with desire as it has with friendship. She thinks the best priests, like novelists, are genuine and engage with other people’s stories.

Mann opened with a long reading from Chapter 1 of her debut novel (I reviewed it here) and said it is about her “three favorite things: sex, death, and religion,” all of which involve a sort of self-emptying. Mark Oakley, dean of St John’s College, Cambridge, interviewed her. He noted that her book has been likened to “Dan Brown on steroids.” Mann laughed but recognizes that, though she’s a ‘serious poet’, her gift as a novelist is for pace. She’s a lover of thrillers and, like Brown, gets obsessed with secrets. Although she and her protagonist, Kitty, are outwardly similar (a rural, working-class background and theological training), she quoted Evelyn Waugh’s dictum that all characters should be based on at least three people. Mann argued that the Church has not dealt as well with desire as it has with friendship. She thinks the best priests, like novelists, are genuine and engage with other people’s stories.

Francis Spufford on Light Perpetual

Mann then interviewed Spufford about his second novel, which arose from his frequent walks to his teaching job at Goldsmiths College in London. A plaque on an Iceland commemorates a World War II bombing that killed 15 children in what was then a Woolworths. He decided to commit an act of “literary resurrection” – but through imaginary people in a made-up, working-class South London location. The idea was to mediate between time and eternity. “All lives are remarkable and exceptional if you look at them up close,” he said. The opening bombing scene is delivered in extreme slow motion and then the book jumps on in 15-year intervals, in a reminder of scale. He read a passage from the end of the book when Ben, a bus conductor who fell in love with a Nigerian woman who took him to her Pentecostal Church, is lying in a hospice bed. It was a beautiful litany of “Praise him” statements, a panorama of everyday life: “Praise him at food banks,” etc. It made for a very moving moment.

Mark Oakley on the books that got him through the pandemic

Oakley, in turn, was interviewed by Spufford – everyone did double duty as speaker and questioner! He mentioned six books that meant a lot to him during lockdown. Three of them I’d read myself and can also recommend: Vesper Flights by Helen Macdonald (my nonfiction book of 2020), Tongues of Fire by Seán Hewitt (one of my top five poetry picks from 2020), and Life’s Too Short to Pretend You’re Not Religious by David Dark. His top read of all, though, is a book I haven’t read but would like to: Featherhood by Charlie Gilmour (see Susan’s review). Rounding out his six were The Act of Living by Frank Tallis, about the psychology of finding fulfillment, and The Hunted by Gabriel Bergmoser, a bleak thriller set in the Outback. He read a prepared sermon-like piece on the books rather than just having a chat about them, which made it a bit more difficult to engage.

Spufford asked him if his reading had been about catharsis. Perhaps for some of those choices, he conceded. Oakley spoke of two lessons learned from lockdown. One is “I am an incarnational Christian” in opposition to the way we’ve all now been reduced to screens, abstract and nonmobile. And secondly, “Don’t be prosaic.” He called literalism a curse and decried the thinness of binary views of the world. “Literature is always challenging your answers, asking who you are when you get beyond what you’re good at.” I thought that was an excellent point, as was his bottom line about books: “It’s not how many you get through, but how many get through to you.”

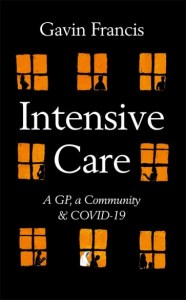

Gavin Francis in Conversation with Louise Welsh

(Wellcome Collection event, February 25th)

Francis, a medical doctor, wrote Intensive Care (I reviewed it here) month by month and sent chapters to his editor as he went along. Its narrative begins barely a year ago and yet it was published in January – a real feat given the usual time scale of book publishing. It was always meant to have the urgent feel of journalism, to be a “hot take,” as he put it, about COVID-19. He finds writing therapeutic; it helps him make sense of and process things as he looks back to the ‘before time’. He remembers first discussing this virus out of China with friends at a Burns Night supper in January 2020. Francis sees so many people using their “retrospecto-scopes” this year and asking what we might have done differently, if only we’d known.

Francis, a medical doctor, wrote Intensive Care (I reviewed it here) month by month and sent chapters to his editor as he went along. Its narrative begins barely a year ago and yet it was published in January – a real feat given the usual time scale of book publishing. It was always meant to have the urgent feel of journalism, to be a “hot take,” as he put it, about COVID-19. He finds writing therapeutic; it helps him make sense of and process things as he looks back to the ‘before time’. He remembers first discussing this virus out of China with friends at a Burns Night supper in January 2020. Francis sees so many people using their “retrospecto-scopes” this year and asking what we might have done differently, if only we’d known.

He shook his head over the unnatural situations that Covid has forced us all into: “we’re gregarious mammals” and yet the virus is spread by voice and touch, so those are the very things we have to avoid. GP practices have had to fundamentally change how they operate, and he foresees telephone triage continuing even after the worst of this is over. He’s noted a rise in antidepressant use over the last year. So the vaccine, to him, is like “liquid hope”; even if not 100% protective, it does seem to prevent deaths and ventilation. Vaccination is like paying for the fire service, he said: it’s not a personal medical intervention but a community thing. This talk didn’t add a lot for me as I’d read the book, but for those who hadn’t, I’m sure it would have been an ideal introduction – and I enjoyed hearing the Scottish accents.

Bookish online events coming up soon: The Rathbones Folio Prize announcement on the 24th and Claire Fuller’s book launch for Unsettled Ground on the 25th.

Saunders’s latest book, A Swim in a Pond in the Rain, is a written version of the graduate-level masterclass in the Russian short story that he offers at Syracuse University, where he has taught in the Creative Writing Program since 1997. His aim here was to “elevate the short story form,” he said. While the book reprints and discusses just seven stories (three by Anton Chekhov, two by Leo Tolstoy, and one each by Nikolai Gogol and Ivan Turgenev), in the class he and his students tackle more like 40. He wants people to read a story, react to the story, and trust that reaction – even if it’s annoyance. “Work with it,” he suggested. “I am bringing you an object to consider” on the route to becoming the author you are meant to be – such is how he described his offer to his students, who have already overcome 1 in 100 odds to be on the elite Syracuse program but might still need to have their academic egos tweaked.

Saunders’s latest book, A Swim in a Pond in the Rain, is a written version of the graduate-level masterclass in the Russian short story that he offers at Syracuse University, where he has taught in the Creative Writing Program since 1997. His aim here was to “elevate the short story form,” he said. While the book reprints and discusses just seven stories (three by Anton Chekhov, two by Leo Tolstoy, and one each by Nikolai Gogol and Ivan Turgenev), in the class he and his students tackle more like 40. He wants people to read a story, react to the story, and trust that reaction – even if it’s annoyance. “Work with it,” he suggested. “I am bringing you an object to consider” on the route to becoming the author you are meant to be – such is how he described his offer to his students, who have already overcome 1 in 100 odds to be on the elite Syracuse program but might still need to have their academic egos tweaked.

Ishiguro’s new novel, Klara and the Sun, was published by Faber yesterday. This conversation with Alex Clark also functioned as its launch event. It’s one of

Ishiguro’s new novel, Klara and the Sun, was published by Faber yesterday. This conversation with Alex Clark also functioned as its launch event. It’s one of

The Booker ceremony was nicely tailored to viewers at home, incorporating brief, informal pre-recorded interviews with each nominated author and a video chat between last year’s winners, Margaret Atwood and Bernardine Evaristo. When Evaristo asked Atwood about the difference between winning the Booker in 2019 versus in 2000, she replied, deadpan, “I was older.” I especially liked the short monologues that well-known UK actors performed from each shortlisted book. Only a few people – the presenter, Evaristo, chair of judges and publisher Margaret Busby, and a string quartet – appeared in the studio, while all the other participants beamed in from other times and places. Stuart is only the second Scottish winner of the Booker, and seemed genuinely touched for this recognition of his tribute to his mother.

The Booker ceremony was nicely tailored to viewers at home, incorporating brief, informal pre-recorded interviews with each nominated author and a video chat between last year’s winners, Margaret Atwood and Bernardine Evaristo. When Evaristo asked Atwood about the difference between winning the Booker in 2019 versus in 2000, she replied, deadpan, “I was older.” I especially liked the short monologues that well-known UK actors performed from each shortlisted book. Only a few people – the presenter, Evaristo, chair of judges and publisher Margaret Busby, and a string quartet – appeared in the studio, while all the other participants beamed in from other times and places. Stuart is only the second Scottish winner of the Booker, and seemed genuinely touched for this recognition of his tribute to his mother.

Back on 18 November, I attended another online event to which I’d gotten a last-minute invitation: a “book club” featuring Tracy Chevalier in conversation with her literary agent, Jonny Geller, on Girl with a Pearl Earring at 20 and her new novel, A Single Thread. In 1996 she sent Geller a letter asking if he’d read Virgin Blue, which she’d written for the MA at the University of East Anglia – the only UK Creative Writing course out there at the time. After VB, she started a contemporary novel set at Highgate Cemetery, where she was a tour guide. It was to be called Live a Little (since a Howard Jacobson title). But shortly thereafter, she was lying in bed one day, looking at a Vermeer print on the wall, and asked herself what the look on the girl’s face meant and who she was. She sent Geller one page of thoughts and he immediately told her to stick Live a Little in a drawer and focus on the Vermeer idea.

Back on 18 November, I attended another online event to which I’d gotten a last-minute invitation: a “book club” featuring Tracy Chevalier in conversation with her literary agent, Jonny Geller, on Girl with a Pearl Earring at 20 and her new novel, A Single Thread. In 1996 she sent Geller a letter asking if he’d read Virgin Blue, which she’d written for the MA at the University of East Anglia – the only UK Creative Writing course out there at the time. After VB, she started a contemporary novel set at Highgate Cemetery, where she was a tour guide. It was to be called Live a Little (since a Howard Jacobson title). But shortly thereafter, she was lying in bed one day, looking at a Vermeer print on the wall, and asked herself what the look on the girl’s face meant and who she was. She sent Geller one page of thoughts and he immediately told her to stick Live a Little in a drawer and focus on the Vermeer idea.

Lastly, Chevalier and Geller talked about her new novel, A Single Thread, which was conceived before Trump and Brexit but had its central themes reinforced by the constant references back to 1930s fascism during the Trump presidency. She showed off the needlepoint spectacles case she’d embroidered for the novel. This wasn’t the first time she’d taken up a craft featured in her fiction: for The Last Runaway she learned to quilt, and indeed still quilts today. Geller likened her to a “method actor,” and jokingly fretted that they’ll lose her to one of these hobbies one day. Chevalier’s work in progress features Venetian glass. I’m already looking forward to it.

Lastly, Chevalier and Geller talked about her new novel, A Single Thread, which was conceived before Trump and Brexit but had its central themes reinforced by the constant references back to 1930s fascism during the Trump presidency. She showed off the needlepoint spectacles case she’d embroidered for the novel. This wasn’t the first time she’d taken up a craft featured in her fiction: for The Last Runaway she learned to quilt, and indeed still quilts today. Geller likened her to a “method actor,” and jokingly fretted that they’ll lose her to one of these hobbies one day. Chevalier’s work in progress features Venetian glass. I’m already looking forward to it.