Literary Wives Club: Novel About My Wife by Emily Perkins (2008)

Although Emily Perkins was a new name to me, the New Zealand author has published five novels and a short story collection. Unfortunately, I never engaged with her London-set Novel About My Wife. On the one hand, it must have been an intriguing challenge for Perkins to inhabit a man’s perspective and examine how a widower might recreate his marriage and his late wife’s mental state. “I can’t speak for Ann[,] obviously, only about her,” screenwriter Tom Stone admits. On the other hand, Tom is so egotistical and self-absorbed that his portrait of Ann is more obfuscating than illuminating.

Although Emily Perkins was a new name to me, the New Zealand author has published five novels and a short story collection. Unfortunately, I never engaged with her London-set Novel About My Wife. On the one hand, it must have been an intriguing challenge for Perkins to inhabit a man’s perspective and examine how a widower might recreate his marriage and his late wife’s mental state. “I can’t speak for Ann[,] obviously, only about her,” screenwriter Tom Stone admits. On the other hand, Tom is so egotistical and self-absorbed that his portrait of Ann is more obfuscating than illuminating.

“If I could build her again using words, I would,” he opens, but that promising start just leads into paragraphs of physical description. Bare facts, such as that Ann was from Sydney and created radiation masks for cancer patients in a hospital, are hardly revealing. We mostly know Ann through her delusions. In her late thirties, when she was three months pregnant with their son Arlo, she was caught in an underground train derailment. Thereafter, she increasingly fell victim to paranoia, believing that she was being stalked and that their house was infested. We’re invited to speculate that pregnancy exacerbated her mental health issues and that postpartum psychosis may have had something to do with her death.

I mostly skimmed the novel, so I may have missed some plot points, but what stood out to me were Tom’s unpleasant depictions of women and complaints about his faltering career. (He’s envious of a new acquaintance, Simon, who’s back and forth to Hollywood all the time for successful screenwriting projects.) Interspersed are seemingly pointless excerpts from Tom’s screenplay about a trip he and Ann took to Fiji. I longed for the balance of another perspective. This had a bit of the flavour of early Maggie O’Farrell, but none of the warmth. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com) ![]()

The main question we ask about the books we read for Literary Wives is:

What does this book say about wives or about the experience of being a wife?

Being generous to Perkins, perhaps the very point she was trying to make is that it’s impossible to get outside of one’s own perspective and understand what’s going on with a spouse, especially one who has mental health struggles. Had Tom been more attentive and supportive, might things have ended differently?

See Becky’s, Kate’s and Kay’s reviews, too! (Naomi is on a break this month.)

Coming up next, in December: The Soul of Kindness by Elizabeth Taylor.

Winter Reading, Part II: “Snow” Books by Coleman, Rice & Whittell

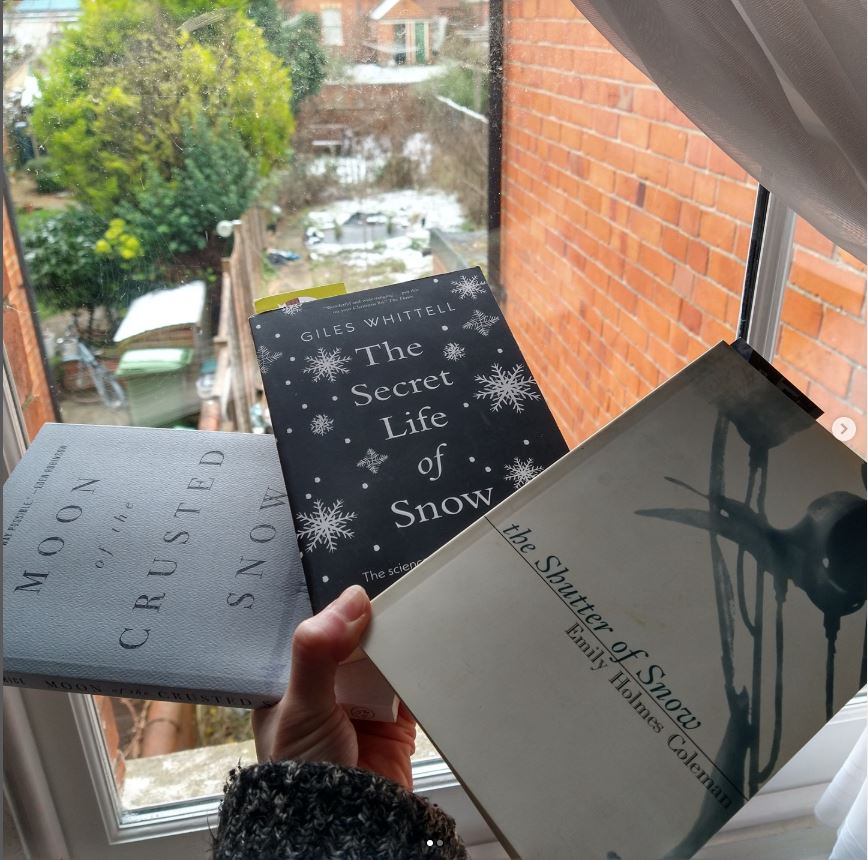

Here I am squeaking in on the day before the spring equinox – when it’s predicted to be warmer than Ibiza here in southern England, as headlines have it – with a few snowy reads that have been on my stack for much of the winter. I started reading this trio when we got a dusting back in January, in case (as proved to be true) it was our only snow of the year. I have an arresting work of autofiction that recreates a period of postpartum psychosis, a mildly dystopian novel by a First Nations Canadian, and a snow-lover’s compendium of science and trivia.

As it happens, I’ll be starting the spring in the middle of We Do Not Part by Han Kang, which is austerely beautiful and eerily snowy: its narrator traverses a blizzard to rescue her friend’s pet bird; and the friend’s mother recalls a village massacre that left piles of snow-covered corpses. Here Kang muses on the power of snow:

As it happens, I’ll be starting the spring in the middle of We Do Not Part by Han Kang, which is austerely beautiful and eerily snowy: its narrator traverses a blizzard to rescue her friend’s pet bird; and the friend’s mother recalls a village massacre that left piles of snow-covered corpses. Here Kang muses on the power of snow:

Snow had an unreality to it. Was this because of its pace or its beauty? There was an accompanying clarity to snow as well, especially snow, drifting snow. What was and wasn’t important were made distinct. Certain facts became chillingly apparent. Pain, for one.

The Shutter of Snow by Emily Holmes Coleman (1930)

Coleman (1899–1974), an expatriate American poet, was part of the Paris literary milieu in the 1920s and then the London scene of the 1930s. (She worked with T.S. Eliot on editing Djuna Barnes’s Nightwood, for instance.) This novella, her only published work of fiction, was based on her experience of giving birth to her son in 1924, suffering from puerperal fever and a mental breakdown, and being incarcerated in Rochester State Hospital. Although the portrait of Marthe Gail is in the omniscient third person, the stream-of-consciousness style – no speech marks or apostrophes, minimal punctuation – recalls unreliable first-person narration. Marthe believes she is Jesus Christ. Her husband Christopher visits occasionally, hoping she’ll soon be well enough to come home to their baby. It’s hard to believe this was written a century ago; I could imagine it being published tomorrow. It is absolutely worth rediscovering. While I admired the weird lyrical prose (“in his heart was growing a stern and ruddy pear … He would make of his heart a stolen marrow bone and clutch snow crystals in the night to his liking”; “This earth is made of tar and every morsel is stuck upon it to wither … there were orange peelings lying in the snow”), the interactions between patients, nurses and doctors got tedious. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury)

Coleman (1899–1974), an expatriate American poet, was part of the Paris literary milieu in the 1920s and then the London scene of the 1930s. (She worked with T.S. Eliot on editing Djuna Barnes’s Nightwood, for instance.) This novella, her only published work of fiction, was based on her experience of giving birth to her son in 1924, suffering from puerperal fever and a mental breakdown, and being incarcerated in Rochester State Hospital. Although the portrait of Marthe Gail is in the omniscient third person, the stream-of-consciousness style – no speech marks or apostrophes, minimal punctuation – recalls unreliable first-person narration. Marthe believes she is Jesus Christ. Her husband Christopher visits occasionally, hoping she’ll soon be well enough to come home to their baby. It’s hard to believe this was written a century ago; I could imagine it being published tomorrow. It is absolutely worth rediscovering. While I admired the weird lyrical prose (“in his heart was growing a stern and ruddy pear … He would make of his heart a stolen marrow bone and clutch snow crystals in the night to his liking”; “This earth is made of tar and every morsel is stuck upon it to wither … there were orange peelings lying in the snow”), the interactions between patients, nurses and doctors got tedious. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury) ![]()

Moon of the Crusted Snow by Waubgeshig Rice (2018)

A mysterious total power outage heralds not just the onset of winter or a temporary crisis but the coming of a new era. For this Anishinaabe community, it will require a return to ancient nomadic, hunter-gatherer ways. I was expecting a sinister dystopian; while there are rumours of a more widespread collapse, the focus is on adaptation versus despair, internal resilience versus external threats. Rice reiterates that Indigenous peoples have often had to rebuild their worlds: “Survival had always been an integral part of their culture. It was their history. The skills they needed to persevere in this northern terrain … were proud knowledge held close through the decades of imposed adversity.” As an elder remarks, apocalypse is nothing new. I was more interested in these ideas than in how they played out in the plot. Evan works snow-ploughs until, with food running short and many falling ill, he assumes the grim task of an undertaker. I was a little disappointed that it’s a white interloper breaks their taboos, but it is interesting how he is compared to the mythical windigo in a dream sequence. As short as this novel is, I found it plodding, especially in the first half. It does pick up from that point (and there is a sequel). I was reminded somewhat of Sherman Alexie. It was probably my first book by an Indigenous Canadian, which was reason enough to read it, though I wonder if I would warm more to his short stories. (Birthday gift from my wish list last year)

A mysterious total power outage heralds not just the onset of winter or a temporary crisis but the coming of a new era. For this Anishinaabe community, it will require a return to ancient nomadic, hunter-gatherer ways. I was expecting a sinister dystopian; while there are rumours of a more widespread collapse, the focus is on adaptation versus despair, internal resilience versus external threats. Rice reiterates that Indigenous peoples have often had to rebuild their worlds: “Survival had always been an integral part of their culture. It was their history. The skills they needed to persevere in this northern terrain … were proud knowledge held close through the decades of imposed adversity.” As an elder remarks, apocalypse is nothing new. I was more interested in these ideas than in how they played out in the plot. Evan works snow-ploughs until, with food running short and many falling ill, he assumes the grim task of an undertaker. I was a little disappointed that it’s a white interloper breaks their taboos, but it is interesting how he is compared to the mythical windigo in a dream sequence. As short as this novel is, I found it plodding, especially in the first half. It does pick up from that point (and there is a sequel). I was reminded somewhat of Sherman Alexie. It was probably my first book by an Indigenous Canadian, which was reason enough to read it, though I wonder if I would warm more to his short stories. (Birthday gift from my wish list last year) ![]()

The Secret Life of Snow: The science and the stories behind nature’s greatest wonder by Giles Whittell (2018)

This is so much like The Snow Tourist by Charlie English it was almost uncanny. Whittell, an English journalist who has written history and travel books, is a snow obsessive and hates that, while he may see a few more major snow events in his lifetime, his children probably won’t experience any in their adulthood. Topics in the chatty chapters include historical research into snowflakes, meteorological knowledge then and now and the ongoing challenge of forecasting winter storms, record-breaking snowfalls and the places still most likely to have snow cover, and the depiction of snow in medieval paintings (like English, he zeroes in on Bruegel) and Bond films. There’s a bit too much on skiing for my liking: it keeps popping up in segments on the Olympics, avalanches, and how famous snow spots are reckoning with their uncertain economic future. It’s a fun and accessible book with many an eye-popping statistic, but, coming as it did a decade after English’s, does sound the alarm more shrilly about the future of snow. As in, we’ll get maybe 15 more years (until 2040), before overall warming means it will only fall as rain. “That idea, like death, is hard to think about without losing your bearings, which is why, aware of my cowardice and moral abdication, I prefer to think of the snowy present and recent past rather than of the uncertain future.” (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury)

This is so much like The Snow Tourist by Charlie English it was almost uncanny. Whittell, an English journalist who has written history and travel books, is a snow obsessive and hates that, while he may see a few more major snow events in his lifetime, his children probably won’t experience any in their adulthood. Topics in the chatty chapters include historical research into snowflakes, meteorological knowledge then and now and the ongoing challenge of forecasting winter storms, record-breaking snowfalls and the places still most likely to have snow cover, and the depiction of snow in medieval paintings (like English, he zeroes in on Bruegel) and Bond films. There’s a bit too much on skiing for my liking: it keeps popping up in segments on the Olympics, avalanches, and how famous snow spots are reckoning with their uncertain economic future. It’s a fun and accessible book with many an eye-popping statistic, but, coming as it did a decade after English’s, does sound the alarm more shrilly about the future of snow. As in, we’ll get maybe 15 more years (until 2040), before overall warming means it will only fall as rain. “That idea, like death, is hard to think about without losing your bearings, which is why, aware of my cowardice and moral abdication, I prefer to think of the snowy present and recent past rather than of the uncertain future.” (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury) ![]()

Whittell’s mention of the U.S. East Coast “Snowmaggedon” of February 2010 had me digging out photos my mother sent me of the aftermath at our family home of the time.

Any wintry reading (or weather) for you lately? Or is it looking like spring?

Young Writer of the Year Award 2020: Shortlist Reviews and Predictions

Being on the shadow panel for the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award was a bookish highlight of 2017 for me. I’m pleased for this year’s panelists, especially blogging friend Marina Sofia, to have had the same opportunity, and I look forward to hearing who they choose as their shadow panel winner on December 3rd and then attending the virtual prize ceremony on December 10th.

At the time of the shortlisting, I happened to have already read Exciting Times by Naoise Dolan and was halfway through Catherine Cho’s memoir Inferno. I got the poetry collection Surge by Jay Bernard out from the library to have another go (after DNFing it last year), and the kind folk of FMcM Associates sent me the other two shortlisted books, a poetry collection and a novel, so that I could follow along with the shadow panel’s deliberations. Here are my brief thoughts on all five nominees.

Surge by Jay Bernard (2019)

As a writer-in-residence at the George Padmore Institute, a research centre for radical Black history, in 2016, Bernard investigated the New Cross Massacre, a fire that killed 13 young people in 1981. In 2017, the tragedy found a horrific echo in the Grenfell Tower fire, which left 72 dead. This debut poetry collection bridges that quarter-century through protest poems from various perspectives, giving voice to victims and their family members and exploring the interplay between race, sexuality and violence. Patois comes in at several points, most notably in “Songbook.” I especially liked “Peg” and “Pride,” and the indictment of government indifference in “Blank”: “It-has-nothing-to-do-with-us today issued this statement: / those involved have defended their actions and been … acquitted / retired with full pay”. On the whole, I found it difficult to fully engage with this collection, but I am reliably informed that Bernard’s protest poems have more impact when performed aloud.

As a writer-in-residence at the George Padmore Institute, a research centre for radical Black history, in 2016, Bernard investigated the New Cross Massacre, a fire that killed 13 young people in 1981. In 2017, the tragedy found a horrific echo in the Grenfell Tower fire, which left 72 dead. This debut poetry collection bridges that quarter-century through protest poems from various perspectives, giving voice to victims and their family members and exploring the interplay between race, sexuality and violence. Patois comes in at several points, most notably in “Songbook.” I especially liked “Peg” and “Pride,” and the indictment of government indifference in “Blank”: “It-has-nothing-to-do-with-us today issued this statement: / those involved have defended their actions and been … acquitted / retired with full pay”. On the whole, I found it difficult to fully engage with this collection, but I am reliably informed that Bernard’s protest poems have more impact when performed aloud.

Readalikes: In Nearby Bushes by Kei Miller, A Portable Paradise by Roger Robinson and Don’t Call Us Dead by Danez Smith

My rating:

Inferno by Catherine Cho (2020)

Cho, a Korean American literary agent based in London, experienced stress-induced postpartum psychosis after the birth of her son. She and her husband had returned to the USA when Cato was two months old to introduce him to friends and family, ending with a big Korean 100-day celebration at her in-laws’ home. Almost as soon as they got to her in-laws’, though, she started acting strangely: she was convinced cameras were watching their every move, and Cato’s eyes were replaced with “devil’s eyes.” She insisted they leave for a hotel, but soon she would be in a hospital emergency room, followed by a mental health ward. Cho alternates between her time in the mental hospital and a rundown of the rest of her life before the breakdown, weaving in her family history and Korean sayings and legends. Twelve days: That was the length of her hospitalization in early 2018, but Cho so painstakingly depicts her mindset that readers are fully immersed in an open-ended purgatory. She captures extremes of suffering and joy in this vivid account. (Reviewed in full here.)

Cho, a Korean American literary agent based in London, experienced stress-induced postpartum psychosis after the birth of her son. She and her husband had returned to the USA when Cato was two months old to introduce him to friends and family, ending with a big Korean 100-day celebration at her in-laws’ home. Almost as soon as they got to her in-laws’, though, she started acting strangely: she was convinced cameras were watching their every move, and Cato’s eyes were replaced with “devil’s eyes.” She insisted they leave for a hotel, but soon she would be in a hospital emergency room, followed by a mental health ward. Cho alternates between her time in the mental hospital and a rundown of the rest of her life before the breakdown, weaving in her family history and Korean sayings and legends. Twelve days: That was the length of her hospitalization in early 2018, but Cho so painstakingly depicts her mindset that readers are fully immersed in an open-ended purgatory. She captures extremes of suffering and joy in this vivid account. (Reviewed in full here.)

Readalikes: An Angel at My Table by Janet Frame and Dear Scarlet by Teresa Wong

My rating:

Exciting Times by Naoise Dolan (2020)

At 22, Ava leaves Dublin to teach English as a foreign language to wealthy preteens in Hong Kong and soon comes to a convenient arrangement with her aloof banker friend, Julian, who lets her live with him without paying rent and buys her whatever she wants. They have sex, yes, but he’s not her boyfriend per se, so when he’s transferred to London for six months, there’s no worry about hard feelings when her new friendship with Edith Zhang turns romantic. It gets a little more complicated, though, when Julian returns and she has to explain these relationships to her two partners and to herself. On the face of it, this doesn’t sound like it would be an interesting plot, and the hook-up culture couldn’t be more foreign to me. But with Ava Dolan has created a funny, deadpan voice that carries the entire novel. I loved the psychological insight, the playfulness with language, and the zingy one-liners (“I wondered if Victoria was a real person or three Mitford sisters in a long coat”). (Reviewed in full here.)

At 22, Ava leaves Dublin to teach English as a foreign language to wealthy preteens in Hong Kong and soon comes to a convenient arrangement with her aloof banker friend, Julian, who lets her live with him without paying rent and buys her whatever she wants. They have sex, yes, but he’s not her boyfriend per se, so when he’s transferred to London for six months, there’s no worry about hard feelings when her new friendship with Edith Zhang turns romantic. It gets a little more complicated, though, when Julian returns and she has to explain these relationships to her two partners and to herself. On the face of it, this doesn’t sound like it would be an interesting plot, and the hook-up culture couldn’t be more foreign to me. But with Ava Dolan has created a funny, deadpan voice that carries the entire novel. I loved the psychological insight, the playfulness with language, and the zingy one-liners (“I wondered if Victoria was a real person or three Mitford sisters in a long coat”). (Reviewed in full here.)

Readalikes: Besotted by Melissa Duclos and Conversations with Friends by Sally Rooney

My rating:

Tongues of Fire by Seán Hewitt (2020)

In the title poem, the arboreal fungus from the cover serves as “a bright, ancestral messenger // bursting through from one realm to another” like “the cones of God, the Pentecostal flame”. This debut collection is alive with striking imagery that draws links between the natural and the supernatural. Sex and grief, two major themes, are silhouetted against the backdrop of nature. Fields and forests are loci of meditation and epiphany, but also of clandestine encounters between men: “I came back often, // year on year, kneeling and being knelt for / in acts of secret worship, and now / each woodland smells quietly of sex”. Hewitt recalls travels to Berlin and Sweden, and charts his father’s rapid decline and death from an advanced cancer. A central section of translations of the middle-Irish legend “Buile Suibhne” is less memorable than the gorgeous portraits of flora and fauna and the moving words dedicated to the poet’s father: “You are not leaving, I know, // but shifting into image – my head / already is haunted with you” and “In this world, I believe, / there is nothing lost, only translated”.

In the title poem, the arboreal fungus from the cover serves as “a bright, ancestral messenger // bursting through from one realm to another” like “the cones of God, the Pentecostal flame”. This debut collection is alive with striking imagery that draws links between the natural and the supernatural. Sex and grief, two major themes, are silhouetted against the backdrop of nature. Fields and forests are loci of meditation and epiphany, but also of clandestine encounters between men: “I came back often, // year on year, kneeling and being knelt for / in acts of secret worship, and now / each woodland smells quietly of sex”. Hewitt recalls travels to Berlin and Sweden, and charts his father’s rapid decline and death from an advanced cancer. A central section of translations of the middle-Irish legend “Buile Suibhne” is less memorable than the gorgeous portraits of flora and fauna and the moving words dedicated to the poet’s father: “You are not leaving, I know, // but shifting into image – my head / already is haunted with you” and “In this world, I believe, / there is nothing lost, only translated”.

Readalikes: Physical by Andrew McMillan and If All the World and Love Were Young by Stephen Sexton

My rating:

Nightingale by Marina Kemp (2020)

Marguerite Demers, a 24-year-old nurse, has escaped Paris to be a live-in carer for elderly Jérôme Lanvier in southern France. From the start, she senses she’s out of place here – “She felt, as always in this village, that she was being observed”. She strikes up a friendship with a fellow outsider, an Iranian émigrée named Suki, who, in this story set in 2002, stands out for wearing a hijab. Everyone knows everyone here, and everyone has history with everyone else – flirtations, feuds, affairs, and more. Brigitte Brochon, unhappily married to a local farmer, predicts Marguerite will be just like the previous nurses who failed to hack it in service to the curmudgeonly Monsieur Lanvier. But Marguerite sticks up for herself and, though plagued by traumatic memories, makes her own bid for happiness. The novel deals sensitively with topics like bisexuality, euthanasia, and family estrangement, but the French provincial setting and fairly melodramatic plot struck me as old-fashioned. Still, the writing is strong enough to keep an eye out for what Kemp writes next. (U.S. title: Marguerite.)

Marguerite Demers, a 24-year-old nurse, has escaped Paris to be a live-in carer for elderly Jérôme Lanvier in southern France. From the start, she senses she’s out of place here – “She felt, as always in this village, that she was being observed”. She strikes up a friendship with a fellow outsider, an Iranian émigrée named Suki, who, in this story set in 2002, stands out for wearing a hijab. Everyone knows everyone here, and everyone has history with everyone else – flirtations, feuds, affairs, and more. Brigitte Brochon, unhappily married to a local farmer, predicts Marguerite will be just like the previous nurses who failed to hack it in service to the curmudgeonly Monsieur Lanvier. But Marguerite sticks up for herself and, though plagued by traumatic memories, makes her own bid for happiness. The novel deals sensitively with topics like bisexuality, euthanasia, and family estrangement, but the French provincial setting and fairly melodramatic plot struck me as old-fashioned. Still, the writing is strong enough to keep an eye out for what Kemp writes next. (U.S. title: Marguerite.)

Readalikes: French-set novels by Joanne Harris and Rose Tremain; The Hoarder by Jess Kidd

My rating:

General thoughts:

After last year’s unexpected winner – Raymond Antrobus for his poetry collection The Perseverance – I would have said that it’s time for a novel by a woman to win. However, I feel like a Dolan win would be too much of a repeat of 2017’s win (for Sally Rooney), and Kemp’s debut novel isn’t quite up to scratch. Much as I enjoyed Inferno, I can’t see it winning over these judges (three of whom are novelists: Kit de Waal, Sebastian Faulks and Tessa Hadley), though it would be suited to the Wellcome Book Prize if that comes back in 2021. So, to my surprise, I think it’s going to be another year for poetry.

I’ve been following the shadow panel’s thoughts via Marina’s blog and the others’ Instagram accounts and it looks like they are united in their admiration for the poetry collections, particularly the Hewitt. That would be my preference, too: I respond better to theme and style in poetry (Hewitt) than to voice and message (Bernard). However, I think that in 2020 the Times may try to trade its rather fusty image for something more woke, bearing in mind the Black Lives Matter significance and the unprecedented presence of a nonbinary author.

My predictions:

Shadow panel winner: Tongues of Fire by Seán Hewitt

Official winner: Surge by Jay Bernard

Have you read anything from this year’s shortlist?

Be(com)ing an ‘Expert’ on Postpartum Depression for #NonficNov

This Being/Becoming/Asking the Expert week of the month-long Nonfiction November challenge is hosted by Rennie of What’s Nonfiction.

I’m also counting this as the first entry in my new “Three on a Theme” series, where I’ll review three books that have something significant in common and tell you which one to pick up if you want to read into the topic for yourself. I have another medical-themed one lined up for this Friday as a second ‘Being the Expert’ entry.

I never set out to read several memoirs of women’s experience of postpartum depression this year; it sort of happened by accident. I started with the graphic memoir and then chanced upon a recent pair of traditional memoirs published in the UK – in fact, I initially pitched them as a dual review to the TLS, but they’d already secured a reviewer for one of the books.

Inferno: A Memoir by Catherine Cho

I was delighted to see this prediction of mine make the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award shortlist. Coincidentally, I was already halfway through the book on my Kindle (via NetGalley) at that point, but its nomination gave me the push to finish in a timely manner. Cho, a Korean American literary agent based in London, experienced stress-induced postpartum psychosis after the birth of her son, Cato. She and her husband James had gone back to the USA when Cato was two months old to introduce him to friends and family, ending with a big Korean 100-day celebration for him at her in-laws’ home in New Jersey. Almost as soon as they got to her in-laws’, though, she started acting strangely: she was convinced there were cameras watching their every move, and Cato’s eyes were replaced with “devil’s eyes.” She insisted they leave for a hotel, but soon she would be in an emergency room, followed by a mental health ward.

I was delighted to see this prediction of mine make the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award shortlist. Coincidentally, I was already halfway through the book on my Kindle (via NetGalley) at that point, but its nomination gave me the push to finish in a timely manner. Cho, a Korean American literary agent based in London, experienced stress-induced postpartum psychosis after the birth of her son, Cato. She and her husband James had gone back to the USA when Cato was two months old to introduce him to friends and family, ending with a big Korean 100-day celebration for him at her in-laws’ home in New Jersey. Almost as soon as they got to her in-laws’, though, she started acting strangely: she was convinced there were cameras watching their every move, and Cato’s eyes were replaced with “devil’s eyes.” She insisted they leave for a hotel, but soon she would be in an emergency room, followed by a mental health ward.

Cho alternates between her time on the New Bridge ward – writing in a notebook, trying to act normal whenever James visited, expressing milk from painfully swollen breasts, and interacting with her fellow patients with all their quirks – and a rundown of the rest of her life before the breakdown. Her Kentucky childhood was marked by her mathematician father’s detachment and the sense that she and her brother were together “in the trenches,” pitted against the world. In her twenties she worked in a New York City corporate law firm and got caught up in an abusive relationship with a man she moved to Hong Kong to be with. All along she weaves in her family’s history and Korean sayings and legends that explain their values.

Twelve days. That was the length of her hospitalization in early 2018, but Cho so painstakingly depicts her mindset that readers are fully immersed in an open-ended purgatory – a terrifying time when she questioned her sanity and whether she was cut out for motherhood. “Koreans believe that happiness can only tempt the fates and that any happiness must be bought with sorrow,” she writes. She captures both extremes, of suffering and joy, in this vivid account.

My rating:

What Have I Done? An honest memoir about surviving postnatal mental illness by Laura Dockrill

Dockrill is a British children’s author. Her style reminded me of others of her contemporaries who do a good line in light, witty, warts-and-all, here’s-what-it’s-really-like-to-be-a-woman books: Dolly Alderton, Caitlin Moran and the like. From a labor that quickly deviated from her birth plan due to an emergency Caesarean to the usual post-baby blues to full-blown psychosis, Dockrill recreates her experience with fluid dialogue and italicized passages of her paranoid imaginings. Her memoir resembles Cho’s in its broad strokes but also in certain particulars, like imagining surveillance cameras and hearing a voice in her head telling her she is a bad mum. I skimmed this one because of a library deadline and because of an overload on similar content. I had a greater affinity for Cho’s literary style compared to the more between-girlfriends, self-help bent of this memoir. With the glossary and resources at the end, though, I’d say this one would be more useful for someone going through the same thing.

Dockrill is a British children’s author. Her style reminded me of others of her contemporaries who do a good line in light, witty, warts-and-all, here’s-what-it’s-really-like-to-be-a-woman books: Dolly Alderton, Caitlin Moran and the like. From a labor that quickly deviated from her birth plan due to an emergency Caesarean to the usual post-baby blues to full-blown psychosis, Dockrill recreates her experience with fluid dialogue and italicized passages of her paranoid imaginings. Her memoir resembles Cho’s in its broad strokes but also in certain particulars, like imagining surveillance cameras and hearing a voice in her head telling her she is a bad mum. I skimmed this one because of a library deadline and because of an overload on similar content. I had a greater affinity for Cho’s literary style compared to the more between-girlfriends, self-help bent of this memoir. With the glossary and resources at the end, though, I’d say this one would be more useful for someone going through the same thing.

My rating:

Dear Scarlet: The Story of My Postpartum Depression by Teresa Wong (2019)

Memoir as letter and as graphic novel. Wong narrates the traumatic birth of her first child and her subsequent postpartum depression in black-and-white sketches that manage to feel breezy and fun despite the heavy subject matter. “I felt lost. I had no maternal instincts and no clue how I was supposed to take care of a baby,” she writes to Scarlet. “Your first two months in the world were the hardest two months of my life.”

Memoir as letter and as graphic novel. Wong narrates the traumatic birth of her first child and her subsequent postpartum depression in black-and-white sketches that manage to feel breezy and fun despite the heavy subject matter. “I felt lost. I had no maternal instincts and no clue how I was supposed to take care of a baby,” she writes to Scarlet. “Your first two months in the world were the hardest two months of my life.”

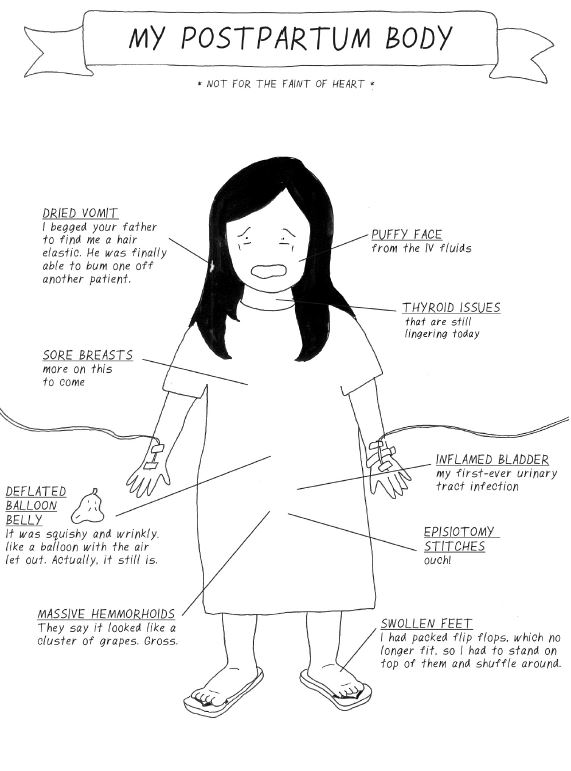

For Wong, a combination of antidepressants, therapy, a postnatal doula, an exercise class, her mother’s help, and her husband’s constant support got her through, and she knows she’s lucky to have had a fairly mild case and to have gotten assistance early on. I loved the “Not for the Faint of Heart” anatomical spreads and the reflections on her mother’s tough early years after arriving in Canada from China.

The drawing and storytelling style is similar to that of Sarah Laing and Debbie Tung. The writing is more striking than the art, though, so I hope that with future work the author will challenge herself to use more color and more advanced designs (from her Instagram page it looks like she is heading that way).

My rating:

My thanks to publicist Beth Parker for the free e-copy for review.

What I learned:

All three authors emphasize that motherhood does not always come naturally; “You might not instantly love your baby,” as Dockrill puts it. There might be a feeling of detachment – from the baby and/or from one’s new body. They all note that postpartum depression is common and that new mothers should not be ashamed of seeking help from medical professionals, baby nurses, family members and any other sources of support.

These two passages were representative for me:

Cho: “I don’t feel a rush of love or an overwhelming weight of responsibility, emotions that I’d been expecting. Instead, I felt curious, like I’d just been introduced to a stranger. He was a creature, an idea, not even human yet, just a being, a life. … I’d thought I would reclaim my body after birth, but instead, it was now a tool, something to sustain life.”

Dockrill: “If childbirth and motherhood are the most natural, universal, common things in the world, the things that women have been doing since the beginning of time, then why does nobody tell us that there’s a good chance that you might not feel like yourself after you have a baby? That you might even lose your head? That you might not ever come back?”

On this topic, I have also read: Birth of a New Brain by Dyane Harwood. There are more book ideas here and here.

On this topic, I have also read: Birth of a New Brain by Dyane Harwood. There are more book ideas here and here.

Nobody Told Me by Hollie McNish, one of my current bedside books, also deals with complicated pregnancy emotions and the chaotic early months of motherhood.

If you read just one, though… Make it Inferno by Catherine Cho.