#ReadingtheMeow2025, Part I: Books by Gustafson, Inaba, Tomlinson and More

It’s the start of the third annual week-long Reading the Meow challenge, hosted by Mallika of Literary Potpourri! For my first set of reviews, I have two lovely memoirs of life with cats, and a few cute children’s books.

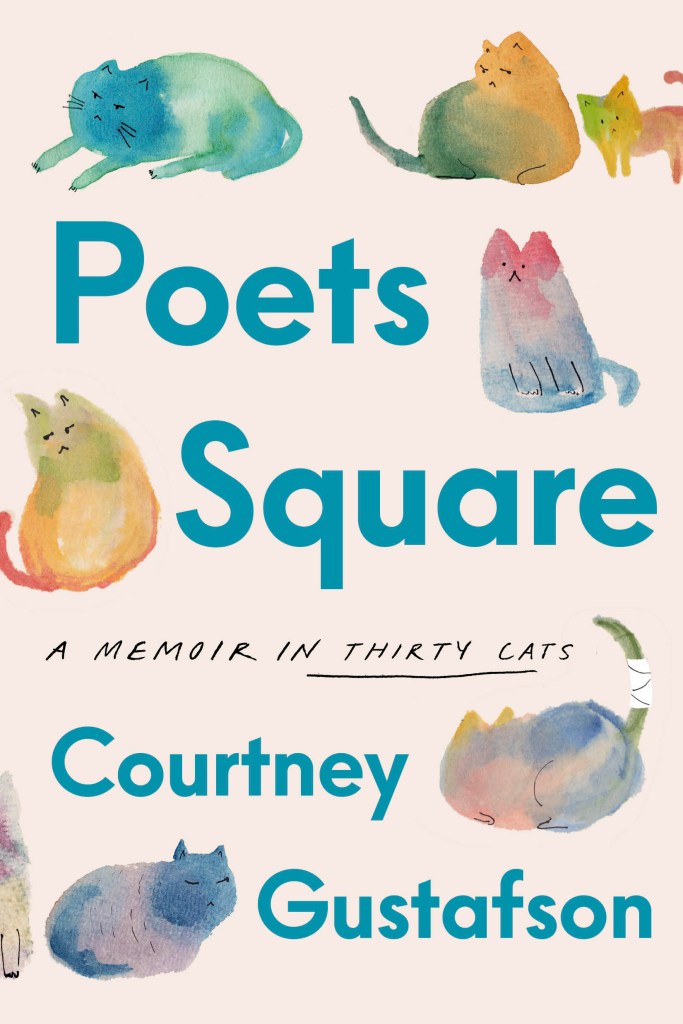

Poets Square: A Memoir in Thirty Cats by Courtney Gustafson (2025)

This was on my Most Anticipated list and surpassed my expectations. Because I’m a snob and knew only that the author was a young influencer, I was pleasantly surprised by the quality of the prose and the depth of the social analysis. After Gustafson left academia, she became trapped in a cycle of dead-end jobs and rising rents. Working for a food bank, she saw firsthand how broken systems and poverty wear people down. She’d recently started feeding and getting veterinary care for the 30 feral cats of a colony in her Poets Square neighbourhood in Tucson, Arizona. They all have unique personalities and interactions, such as Sad Boy and Lola, a loyal bonded pair; and MK, who made Georgie her surrogate baby. Gustafson doled out quirky names and made the cats Instagram stars (@PoetsSquareCats). Soon she also became involved in other local trap, neuter and release initiatives.

That the German translation is titled “Cats and Capitalism” gives an idea of how the themes are linked here: cat colonies tend to crop up where deprivation prevails. Stray cats, who live short and difficult lives, more reliably receive compassion than struggling people for whom the same is true. TNR work takes Gustafson to places where residents are only just clinging on to solvency or where hoarding situations have gotten out of control. I also appreciated a chapter that draws a parallel between how she has been perceived as a young woman and how female cats are deemed “slutty.” (Having a cat spayed so she does not undergo constant pregnancies is a kindness.) She also interrogates the “cat mom” stereotype through an account of her relationship with her mother and her own decision not to have children.

Gustafson knows how lucky she is to have escaped a paycheck-to-paycheck existence. Fame came seemingly out of nowhere when a TikTok video she posted about preparing a mini Thanksgiving dinner for the cats went viral. Social media and cat rescue work helped a shy, often ill person be less lonely, giving her “a community, a sense of rootedness, a purpose outside myself.” (Moreover, her Internet following literally ensured she had a place to live: when her rental house was being sold out from under her, a crowdfunding campaign allowed her to buy the house and save the cats.) However, they have also made her aware of a “constant undercurrent of suffering.” There are multiple cat deaths in the book, as you might expect. The author has become inured over time; she allows herself five minutes to cry, then moves on to help other cats. It’s easy to be overwhelmed or succumb to despair, but she chooses to focus on the “small acts of care by people trying hard” that can reduce suffering.

With its radiant portraits of individual cats and its realistic perspective on personal and collective problems, this is both a cathartic memoir and a probing study of how we build communities of care in times of hardship.

With thanks to Fig Tree (Penguin) for the proof copy for review.

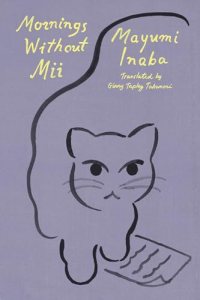

Mornings without Mii by Mayumi Inaba (1999; 2024)

[Translated from Japanese by Ginny Tapley Takemori]

Inaba (1950–2014) was an award-winning novelist and poet. I can’t think why it took 25 years for this to be translated into English but assume it was considered a minor work of hers and was brought out to capitalize on the continuing success of cat-themed Japanese literature from The Guest Cat onward. Interestingly, it’s titled Mornings with Mii in the UK, which shifts the focus and is truer to the contents. Yes, by the end, Inaba is without Mii and dreading the days ahead, but before that she got 20 years of companionship. One day in the summer of 1977, Inaba heard a kitten’s cries on the breeze and finally located it, stuck so high in a school fence that someone must have left her there deliberately. The little fleabitten calico was named after the sound of her cry and ever after was afraid of heights.

Inaba traces the turning of the seasons and the passing of the years through the changes they brought for her and for Mii. When she separated, moved to a new part of Tokyo, and started devoting her evenings to writing in addition to her full-time job, Mii was her closest friend. The new apartment didn’t have any green space, so instead of wandering in the woods Mii had to get used to exercising in the corridors. There were some scares: a surprise pregnancy nearly killed her, and once she went missing. And then there was the inevitable decline. Mii’s intestinal issues led to incontinence. For four years, Inaba endured her home reeking of urine. Many readers may, like me, be taken aback by how long Inaba kept Mii alive. She manually assisted the cat with elimination for years; 20 days passed between when Mii stopped eating and when she died. On the plus side, she got a “natural” death at home, but her quality of life in these years is somewhat alarming. I cried buckets through these later chapters, thinking of the friendship and intimate communion I had with Alfie. I can understand why Inaba couldn’t bear to say goodbye to Mii any earlier, especially because she’d lived alone since her divorce.

Inaba traces the turning of the seasons and the passing of the years through the changes they brought for her and for Mii. When she separated, moved to a new part of Tokyo, and started devoting her evenings to writing in addition to her full-time job, Mii was her closest friend. The new apartment didn’t have any green space, so instead of wandering in the woods Mii had to get used to exercising in the corridors. There were some scares: a surprise pregnancy nearly killed her, and once she went missing. And then there was the inevitable decline. Mii’s intestinal issues led to incontinence. For four years, Inaba endured her home reeking of urine. Many readers may, like me, be taken aback by how long Inaba kept Mii alive. She manually assisted the cat with elimination for years; 20 days passed between when Mii stopped eating and when she died. On the plus side, she got a “natural” death at home, but her quality of life in these years is somewhat alarming. I cried buckets through these later chapters, thinking of the friendship and intimate communion I had with Alfie. I can understand why Inaba couldn’t bear to say goodbye to Mii any earlier, especially because she’d lived alone since her divorce.

This memoir really captures the mixture of joy and heartache that comes with loving a pet. It’s an emotional connection that can take over your life in a good way but leave you bereft when it’s gone. There is nostalgia for the good days with Mii, but also regret and a heavy sense of responsibility. A number of the chapters end with a poem about Mii, but the prose, too, has haiku-like elegance and simplicity. It’s a beautiful book I can strongly recommend. (Read via Edelweiss)

let’s sleep

So as not to hear your departing footsteps

She won’t be here next year I know

I know we won’t have this time again

On this bright afternoon overcome with an unfathomable sadness

The greenery shines in my cat’s gentle eyes

I didn’t have any particular faith, but the one thing I did believe in was light. Just being in warm light, I could be with the people and the cat I had lost from my life. My mornings without Mii would start tomorrow. … Mii had returned to the light, and I would still be able to meet her there hundreds, thousands of times again.

The Cat Who Wanted to Go Home by Jill Tomlinson (1972)

Suzy the cat lives in a French seaside village with a fisherman and his family of four sons. One day, she curls up to sleep in a basket only to wake up airborne – it’s a hot air balloon, taking her to England! Here the RSPCA place her with old Auntie Jo, who feeds her well, but Suzy longs to get back home. “Chez-moi” is her constant cry, which everyone thinks is an awfully funny way to say miaow (“She purred in French, [too,] but purring sounds the same all over the world”). Each day she hops into the basket of Auntie Jo’s bike for a ride to town to try a new route over the sea: in a kayak, on a surfboard, paddling alongside a Channel swimmer, and so on. Each attempt fails and she returns to her temporary lodgings: shared with a parrot named Biff and comfortable, yet not quite right. Until one day… This is a sweet little story (a 77-page paperback) for new readers to experience along with a parent, with just enough repetition to be soothing and a reassuring message about the benevolence of strangers. Susan Hellard’s illustrations are charming. (Secondhand – local library book sale)

Suzy the cat lives in a French seaside village with a fisherman and his family of four sons. One day, she curls up to sleep in a basket only to wake up airborne – it’s a hot air balloon, taking her to England! Here the RSPCA place her with old Auntie Jo, who feeds her well, but Suzy longs to get back home. “Chez-moi” is her constant cry, which everyone thinks is an awfully funny way to say miaow (“She purred in French, [too,] but purring sounds the same all over the world”). Each day she hops into the basket of Auntie Jo’s bike for a ride to town to try a new route over the sea: in a kayak, on a surfboard, paddling alongside a Channel swimmer, and so on. Each attempt fails and she returns to her temporary lodgings: shared with a parrot named Biff and comfortable, yet not quite right. Until one day… This is a sweet little story (a 77-page paperback) for new readers to experience along with a parent, with just enough repetition to be soothing and a reassuring message about the benevolence of strangers. Susan Hellard’s illustrations are charming. (Secondhand – local library book sale)

And a couple of other children’s books:

Mittens for Kittens and Other Rhymes about Cats, ed. Lenore Blegvad; illus. Erik Blegvad (1974) – A selection of traditional English and Scottish nursery rhymes, a few of them true to the nature of cats but most of them just nonsensical. You’ve got to love the drawings, though. (Secondhand – Hay Castle honesty shelves)

Mittens for Kittens and Other Rhymes about Cats, ed. Lenore Blegvad; illus. Erik Blegvad (1974) – A selection of traditional English and Scottish nursery rhymes, a few of them true to the nature of cats but most of them just nonsensical. You’ve got to love the drawings, though. (Secondhand – Hay Castle honesty shelves)

Scaredy Cat by Stuart Trotter (2007) – Rhyming couplets about everyday childhood fears and what makes them better. I thought it unfortunate that the young cat is afraid of other creatures; to be afraid of dogs is understandable, but three pages about not liking invertebrates is the wrong message to be sending. (Little Free Library)

Scaredy Cat by Stuart Trotter (2007) – Rhyming couplets about everyday childhood fears and what makes them better. I thought it unfortunate that the young cat is afraid of other creatures; to be afraid of dogs is understandable, but three pages about not liking invertebrates is the wrong message to be sending. (Little Free Library)

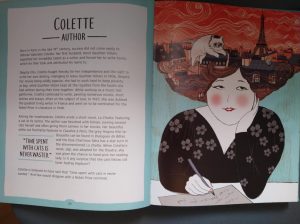

The only name on the cover is Lulu Mayo, who does the illustrations. That’s your clue that the text (by Justine Solomons-Moat) is pretty much incidental; this is basically a YA mini coffee table book. I found it pleasant enough to read bits of at bedtime but it’s not about to win any prizes. (I mean, it prints “prolificate” twice; that ain’t a word. Proliferate is.) Among the famous cat ladies given one-page profiles are Georgia O’Keeffe, Jacinda Ardern, Vivien Leigh, and Anne Frank. I hadn’t heard of the Scottish Fold cat breed, but now I know that they’ve become popular thanks Taylor Swift. The few informational interludes are pretty silly, though I did actually learn that a cat heads straight for the non-cat person in the room (like our friend Steve) because they find eye contact with strangers challenging so find the person who’s ignoring them the least threatening. I liked the end of the piece on Judith Kerr: “To her, cats were symbols of home, sources of inspiration and constant companions. It’s no wonder that she once observed, ‘they’re very interesting people, cats.’” (Christmas gift, secondhand)

The only name on the cover is Lulu Mayo, who does the illustrations. That’s your clue that the text (by Justine Solomons-Moat) is pretty much incidental; this is basically a YA mini coffee table book. I found it pleasant enough to read bits of at bedtime but it’s not about to win any prizes. (I mean, it prints “prolificate” twice; that ain’t a word. Proliferate is.) Among the famous cat ladies given one-page profiles are Georgia O’Keeffe, Jacinda Ardern, Vivien Leigh, and Anne Frank. I hadn’t heard of the Scottish Fold cat breed, but now I know that they’ve become popular thanks Taylor Swift. The few informational interludes are pretty silly, though I did actually learn that a cat heads straight for the non-cat person in the room (like our friend Steve) because they find eye contact with strangers challenging so find the person who’s ignoring them the least threatening. I liked the end of the piece on Judith Kerr: “To her, cats were symbols of home, sources of inspiration and constant companions. It’s no wonder that she once observed, ‘they’re very interesting people, cats.’” (Christmas gift, secondhand)

Last year I read the previous book,

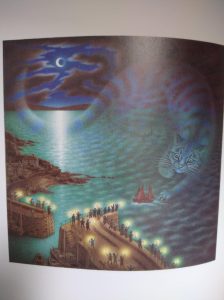

Last year I read the previous book,  The Mousehole Cat by Antonia Barber; illus. Nicola Bayley (1990) – The town of Mousehole in Cornwall (the far southwest of England) relies on fishing. Old Tom brings some of his catch home every day for his cat Mowzer; they have a household menu with a different fishy dish for each day of the week. One winter a storm prevents the fishing boats from leaving the cove and the people – and kitties – start to starve. Tom decides he’ll go out in his boat anyway, and Mowzer goes along to sing and tame the Great Storm-Cat. This story of bravery was ever so cute, words and pictures both, and I especially liked how Mowzer considers Tom her pet. (Free from a neighbour)

The Mousehole Cat by Antonia Barber; illus. Nicola Bayley (1990) – The town of Mousehole in Cornwall (the far southwest of England) relies on fishing. Old Tom brings some of his catch home every day for his cat Mowzer; they have a household menu with a different fishy dish for each day of the week. One winter a storm prevents the fishing boats from leaving the cove and the people – and kitties – start to starve. Tom decides he’ll go out in his boat anyway, and Mowzer goes along to sing and tame the Great Storm-Cat. This story of bravery was ever so cute, words and pictures both, and I especially liked how Mowzer considers Tom her pet. (Free from a neighbour)