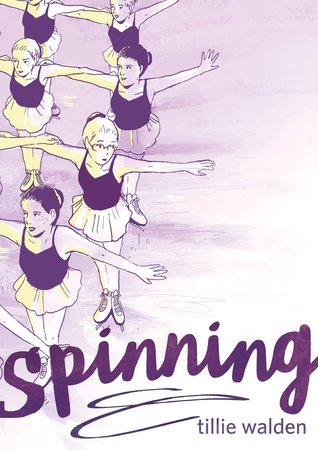

Spinning by Tillie Walden (A Graphic Memoir)

I’m uncomfortable with the term “graphic memoir,” which to me connotes a memoir with graphically violent or sexual content. However, it seems to be accepted parlance nowadays for a graphic novel that’s autobiographical rather than fictional. Tillie Walden’s Spinning is in the same vein as Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home and Craig Thompson’s Blankets: a touching coming-of-age story delivered through the medium of comics.

Specifically, this is about the 12 years Walden spent in the competitive figure skating world. She grew up in New Jersey, and when the family moved to Austin, Texas the bullying she’d experienced in her previous school continued. Mornings started at 4 a.m. when she got up for individual skating lessons; after school she had synchronized skating practice at another rink.

Specifically, this is about the 12 years Walden spent in the competitive figure skating world. She grew up in New Jersey, and when the family moved to Austin, Texas the bullying she’d experienced in her previous school continued. Mornings started at 4 a.m. when she got up for individual skating lessons; after school she had synchronized skating practice at another rink.

These years were full of cello lessons, unrequited crushes and skating competitions she rode to with her friend Lindsay and Lindsay’s mother. The femininity of the skating world – the slicked-back buns and thick make-up; the way every girl was made to look the same – chafed with Walden because she’d known since age five that she was gay. All told, she was disillusioned with what once seemed like her whole life:

Skating changed when I came to Texas. It wasn’t strict or beautiful or energizing any more. Now it just felt dull and exhausting. I couldn’t understand why I should keep skating after it lost all its shine.

Every chapter is named after a different skating move: waltz jump, axel, camel spin, etc. Walden’s drawing style initially reminded me most of This One Summer by Jillian and Mariko Tamaki, which is also about teens finding their way in the world and shares the same mostly purple and gray coloring. Walden’s work is more sketch-like, and also includes yellow on certain pages. The last third or so of the book is the most momentous: between when Walden comes out at 15 and when she gives up skating at 17.

Believe it or not, Walden was born in 1996 and this is her fourth book. She’s already won two Ignatz Awards. I felt this book would have benefited from more hindsight: time to mull over her skating experience and figure out what it all meant. The Author’s note at the end struck me as particularly shallow, like this project was about quick catharsis rather than considered reflection. However, the book’s scope (nearly 400 pages) is impressive, and Walden is adept at capturing the emotional milestones of her early life.

Published in the UK on September 12th. With thanks to Paul Smith of SelfMadeHero – celebrating its 10th anniversary this year – for the free copy for review.

My rating:

Gauguin Gets the Graphic Novel Treatment

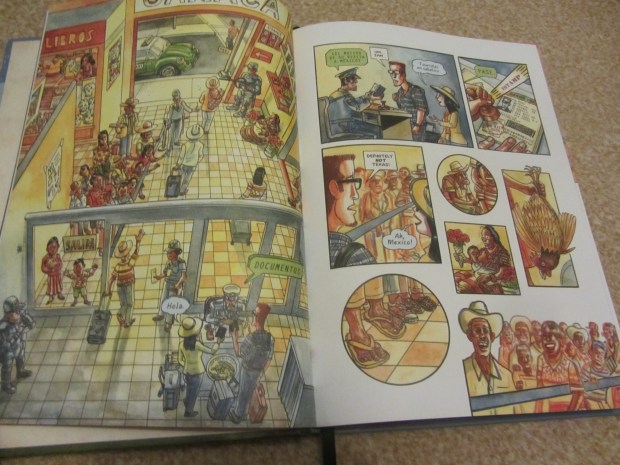

Fabrizio Dori’s Gauguin: The Other World is the third graphic novel I’ve reviewed from SelfMadeHero’s “Art Masters” series, after Munch and Vincent. Like those previous volumes, it delivers salient snippets of biography alongside drawings that cleverly echo the subject’s artistic style. Here the focus is on the last 12 years of Paul Gauguin’s life (1848–1903), which were largely spent in the South Pacific.

Fabrizio Dori’s Gauguin: The Other World is the third graphic novel I’ve reviewed from SelfMadeHero’s “Art Masters” series, after Munch and Vincent. Like those previous volumes, it delivers salient snippets of biography alongside drawings that cleverly echo the subject’s artistic style. Here the focus is on the last 12 years of Paul Gauguin’s life (1848–1903), which were largely spent in the South Pacific.

The book opens with a macro, cosmic view – the myth of the origin of Tahiti and a prophecy of fully clothed, soulless men arriving in a great canoe – before zeroing in on Gauguin’s arrival in June 1891. Although he returned to Europe in 1893–5, Tahiti and the Marquesas Islands would be his final homes. This is all covered in a whirlwind Chapter 1 that ends by, Christmas Carol-like, introducing a Spirit (as pictured in his 1892 painting Manaó Tupapaù (Spirit of the Dead Watching)) who will lead Gauguin – in a morphine haze on his deathbed in 1903 – and readers on a tour through his past.

Gauguin grew up in Peru and Paris, and at age 17 joined the crew of a merchant marine vessel to South America and the West Indies. Back in Paris, he tried to make a living as a stockbroker and salesman while developing as a self-taught artist. He married Mette, a Danish woman, but left her and their children behind in Copenhagen when he departed for Tahiti. The paintings he sent back were unprofitable, and she soon came to curse his career choice.

The locals called Gauguin “the man who makes men” for his skill in portraiture, but also “the woman man” because he wore his hair long. He moved from Papeete, Tahiti’s European-style colonial town, to a cabin in the woods to become more like a savage, and also explored the ghost-haunted island interior. Teura came to live with him as his muse and his lover.

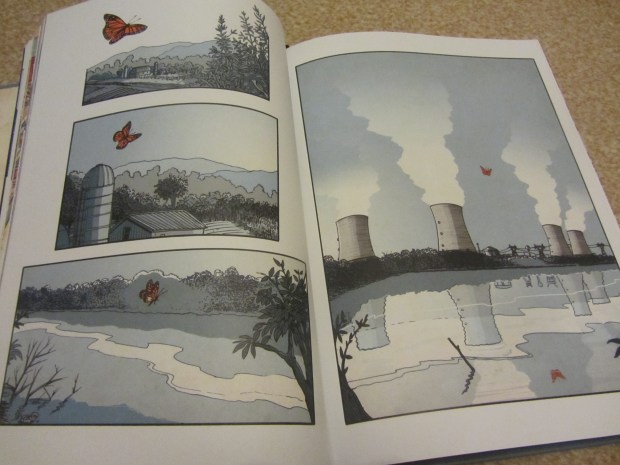

The book is full of wonderful colors and spooky imagery. The palette shifts to suit the mood: dusky blue and purple for the nighttime visit of the Spirit, contrasting with lush greens, pinks and orange for other island scenes and simple ocher and black for the sequences where Gauguin is justifying his decisions. The black-robed, hollow-faced Spirit reminded me of similar figures imagined by Ingmar Bergman and Hayao Miyazaki – could these film directors have been inspired by Gauguin’s Polynesian emissary of death?

Overall this struck me as a very original and atmospheric way of delivering a life story. Although the font is a little bit difficult to read and I ultimately preferred the art to the narration, they still combine to build a portrait of a brazen genius who shunned conventional duties to pursue his art and cultivate the primitive tradition in new ways. Gauguin ends with a short sequence set in Paris in 1907, as Pablo Picasso, fired up by a Gauguin retrospective show, declares, “We must break with formal beauty. We must be savages.”

I appreciated this brief peek into the future, as well as the five-page appendix of critical and biographical information on Gauguin contributed by art critic Céline Delavaux. What I said about Vincent holds true here too: I’d recommend this to anyone with an interest in the lives of artists, whether you think you’re a fan of graphic novels or not. It will be particularly intriguing to see how Dori’s vision of Gauguin compares to that in W. Somerset Maugham’s The Moon and Sixpence, which I plan to start soon.

With thanks to Paul Smith of SelfMadeHero – celebrating its 10th anniversary this year – for the review copy. Translated from the French by Edward Gauvin.

My rating:

Munch, Steffen Kverneland (graphic novel)

Munch is my second biography in graphic novel form from SelfMadeHero, following on from a life of Agatha Christie that I reviewed last month. Norwegian painter Edvard Munch (1863–1944) is, of course, best known for The Scream, but I learned a lot more about his work through this striking visual tour curated by illustrator Steffen Kverneland. Much of the text accompanying Kverneland’s images is from authentic primary sources: Munch’s diaries and letters, his contemporaries’ responses to his art, and so on.

Munch is my second biography in graphic novel form from SelfMadeHero, following on from a life of Agatha Christie that I reviewed last month. Norwegian painter Edvard Munch (1863–1944) is, of course, best known for The Scream, but I learned a lot more about his work through this striking visual tour curated by illustrator Steffen Kverneland. Much of the text accompanying Kverneland’s images is from authentic primary sources: Munch’s diaries and letters, his contemporaries’ responses to his art, and so on.

Munch’s mother died early in his life, and sickroom and deathbed scenes were to permeate his work. “Disease and insanity and death were the black angels that stood by my cradle,” he wrote. “A mother who died early – gave me the seed of consumption – a distraught father – piously religious, verging on madness – gave me the seeds of insanity.” His first solo show opened in Kristiania (now Oslo) in 1889. Three and a half years later scandal erupted when his exhibition in Berlin was closed down. The establishment disapproved of the Impressionist influence in his work and thought he showed a lack of artistic technique. As it turned out, having his show shut down was the best publicity he ever could have asked for.

Kverneland shows different incarnations of Munch’s most famous pieces, such as Madonna, The Girls on the Bridge and The Scream. He also traces the painter’s important relationships, such as his friendship with playwright August Strindberg and his pursuit of the various women who inspired his nudes. In 1895, the writer Sigbjørn Obstfelder gave a lecture on Munch’s art. His appreciation included the following:

As no other Norwegian painter, Munch has focused on essential questions – has caused the deepest subjects to quiver. Before, one painted landscapes and everyday life – Munch paints human beings in all their shapes – even the beastly human. He finds his subjects where the emotions are strongest. Munch is one of the genuine artists who can shift boundaries.

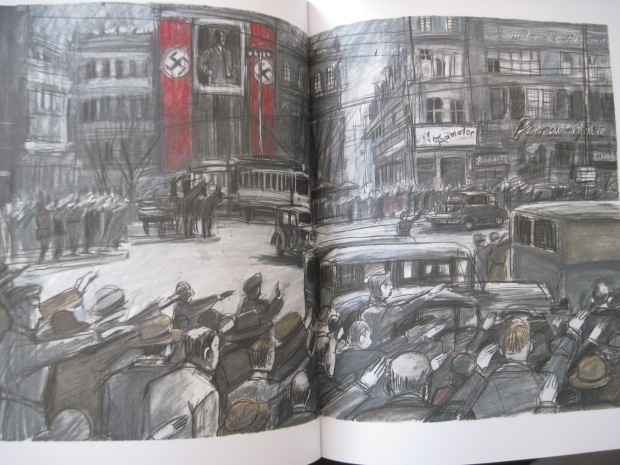

This is a visually remarkable book, with various styles coexisting sometimes on the same page. Sometimes Munch is portrayed like a superhero in a comic (often with a hugely exaggerated chin); other times the images are more like photographs or nineteenth-century portraits. Pen sketches alternate with color spreads in which red, orange, sepia and flesh tones and black dominate. Some of my most admired individual panels have angular faces drawn in almost kaleidoscopic fragments. Strindberg’s is the most frighteningly fractured face, with triangles and trapezoids emphasizing his angry expression.

There’s also a meta aspect to this work: Kverneland depicts his travels with his friend Lars Fiske to sites associated with Munch, again using everything from black-and-white sketches to color photographs. These were, I’m afraid, my least favorite parts of the book: the friends’ raunchy, booze-filled banter has not translated well, and the style of some of their scenes is among the most cartoon-ish.

“Munch had become a monk whose life was devoted to art” is one of the last lines of the graphic novel. It’s a nice summation of what has gone before – with that wordplay especially remarkable given that this is a work in translation. I haven’t come away with a particularly clear sense of the trajectory of Munch’s life, but that’s probably not the point of a deliberately splintered biography like this one.

Kverneland worked on the book for seven years. First published in 2013, it won Norway’s Brage Prize for Literature. This is the fourth installment in SelfMadeHero’s “Art Masters” series, after Pablo, Vincent and Rembrandt. I can highly recommend it to you if you are already a fan of Munch’s work. However, if, like me, you look to graphic novels to also tell you a good story, you might come away slightly disappointed.

With thanks to the publisher, SelfMadeHero, for the free copy. Translated from the Norwegian by Francesca M. Nichols.

My rating:

Note: I’m traveling until the 24th so won’t be responding to comments right away, but will be sure to catch up soon after I’m back. I always welcome your thoughts!

Agatha Christie’s Life as a Graphic Novel

Agatha, a biography in graphic novel form written by Anne Martinetti and Guillaume Lebeau and illustrated by Alexandre Franc, opens – appropriately – with the real-life mystery at the heart of Agatha Christie’s story. In December 1926 the celebrated crime novelist disappeared, prompting a full-scale police investigation. She had abandoned her car by a lake in Surrey and traveled by train to Harrogate, where she checked into a hotel under a false name. Was it all an elaborate act of revenge for her husband’s philandering? Christie strikes up a conversation with Hercule Poirot, her most famous creation, in the hotel room, while back in London a clairvoyant is brought in to confirm she is alive. The medium’s look into Christie’s past sets up the novel’s first half as an extended flashback giving her history up until 1926.

Agatha, a biography in graphic novel form written by Anne Martinetti and Guillaume Lebeau and illustrated by Alexandre Franc, opens – appropriately – with the real-life mystery at the heart of Agatha Christie’s story. In December 1926 the celebrated crime novelist disappeared, prompting a full-scale police investigation. She had abandoned her car by a lake in Surrey and traveled by train to Harrogate, where she checked into a hotel under a false name. Was it all an elaborate act of revenge for her husband’s philandering? Christie strikes up a conversation with Hercule Poirot, her most famous creation, in the hotel room, while back in London a clairvoyant is brought in to confirm she is alive. The medium’s look into Christie’s past sets up the novel’s first half as an extended flashback giving her history up until 1926.

Agatha Miller was raised in a wealthy household in Torquay, Devon. I never knew that she was a flaming redhead or that her father was American. His death when she was 11 was an early pall on an idyllic childhood of outdoor exploration and escape into books – even though her mother opined, “No child ought to be allowed to read until the age of 8. Better for the eyes and the brain.” She first turned her hand to writing while laid up in bed in 1908, completing her first story in two days. She and her mother took an exciting trip to Egypt, and in 1912 she met Lieutenant Archibald Christie at a ball. During the First World War she was a nurse at the town hospital in Torquay, where she came across a Belgian refugee who – at least in the authors’ theory – served as the inspiration for Poirot.

The Christies’ only daughter, Rosalind, was born in 1919. The following year The Mysterious Affair at Styles, the first Poirot mystery, was published. Christie’s career successes are intercut with her round-the-world travels (portrayed as sepia photographs), marriage difficulty and a new romance with archaeologist Max Mallowan, and the occasional intrusion of real-world events like World War II.

Meanwhile, her invented detectives jockey for her attention: not just Poirot, but Miss Marple and Tommy and Tuppence too. You have to suspend your disbelief during these scenes. I don’t think the authors are literally suggesting that Christie hallucinated conversations with her characters. Rather, it’s a whimsical way of imagining how her detectives took on lives of their own and became ‘real people’ she cared for yet found exasperating – she often threatens to do away with Poirot as Arthur Conan Doyle tried to do with Sherlock Holmes. There were only a couple of pages where I felt that a conversation with Poirot was a false way of conveying information. For the most part, this strategy works well; when coupled with the opening scene in 1926, it keeps the biography from being too much of a chronological slog.

Meanwhile, her invented detectives jockey for her attention: not just Poirot, but Miss Marple and Tommy and Tuppence too. You have to suspend your disbelief during these scenes. I don’t think the authors are literally suggesting that Christie hallucinated conversations with her characters. Rather, it’s a whimsical way of imagining how her detectives took on lives of their own and became ‘real people’ she cared for yet found exasperating – she often threatens to do away with Poirot as Arthur Conan Doyle tried to do with Sherlock Holmes. There were only a couple of pages where I felt that a conversation with Poirot was a false way of conveying information. For the most part, this strategy works well; when coupled with the opening scene in 1926, it keeps the biography from being too much of a chronological slog.

With the exception of the sepia-tinged travel sections, this is a book packed with bright colors, particularly with Christie’s flash of red hair animating the first three quarters. It finishes with a timeline of Christie’s life and a complete bibliography of her works – no doubt invaluable references for diehard fans. I’ve only read one or two Christie books myself (my mother is the real devotee), but I enjoyed this quick peek into a legendary writer’s life. I was reminded of just how broad her reach was: from Hollywood studios to the West End, where The Mousetrap has been showing for a record-breaking 63 years. Her influence cannot be denied.

With thanks to the publisher, SelfMadeHero, for the free copy. Translated from the French by Edward Gauvin. (This one is in paperback!)

My rating:

Are you an Agatha Christie fan? Does this tempt you to read more by or about her?

I’ve only ever read one M.R. James piece before, in an anthology of stories about libraries. This was perhaps not an ideal way to encounter his ghost stories for the first time. Though all four (“Number 13,” “Count Magnus,” “Oh, Whistle and I Will Come to You, My Lad” and “The Treasure of Abbot Thomas”) are adapted by the same pair, Leah Moore and John Reppion, each is illustrated by a different artist, so the drawing style ranges from rounded and minimalist to an angular, watercolor Marvel style. The stories have thematic links of research, travel, archaeological discovery and antiquities. Very often there are found documents that must be interpreted. Several narrators are scholars coming across unexplained phenomena: a hotel room that appears and disappears, a sarcophagus lid that opens on its own, a storm summoned by a whistle, and so on.

I’ve only ever read one M.R. James piece before, in an anthology of stories about libraries. This was perhaps not an ideal way to encounter his ghost stories for the first time. Though all four (“Number 13,” “Count Magnus,” “Oh, Whistle and I Will Come to You, My Lad” and “The Treasure of Abbot Thomas”) are adapted by the same pair, Leah Moore and John Reppion, each is illustrated by a different artist, so the drawing style ranges from rounded and minimalist to an angular, watercolor Marvel style. The stories have thematic links of research, travel, archaeological discovery and antiquities. Very often there are found documents that must be interpreted. Several narrators are scholars coming across unexplained phenomena: a hotel room that appears and disappears, a sarcophagus lid that opens on its own, a storm summoned by a whistle, and so on.

In Hurley’s Lancashire farmland setting, Devil’s Day is a regional Halloween-time ritual when the locals serve up the firstborn lamb of spring as a sacrifice to ward off the Devil’s shape-shifting appearance in the human or animal flock. Is it all a bit of fun, or necessary for surviving supernatural threat? We see the year’s turning through the eyes of John Pentecost, now settled back on his ancestral land with his wife, Kat, and their blind son, Adam. However, he focuses on two points from his past: his bullied childhood and a visit home early on in his marriage that coincided with the funeral of his grandfather, “the Gaffer”. The Endlands is a tight-knit community with a long history of being cut off from everywhere else, which makes it an awfully good place to keep secrets.

In Hurley’s Lancashire farmland setting, Devil’s Day is a regional Halloween-time ritual when the locals serve up the firstborn lamb of spring as a sacrifice to ward off the Devil’s shape-shifting appearance in the human or animal flock. Is it all a bit of fun, or necessary for surviving supernatural threat? We see the year’s turning through the eyes of John Pentecost, now settled back on his ancestral land with his wife, Kat, and their blind son, Adam. However, he focuses on two points from his past: his bullied childhood and a visit home early on in his marriage that coincided with the funeral of his grandfather, “the Gaffer”. The Endlands is a tight-knit community with a long history of being cut off from everywhere else, which makes it an awfully good place to keep secrets. This was so cool! I feel like I’d never experienced a “real” Mitchell book before (having only read The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet, which is in some ways the odd one out), and I was impressed by how he brings everything together in this short novel. Every nine years between 1979 and 2015, a different visitor gets sucked into the treacherous world-within-a-world of the Grayer twins’ Slade House. This dilapidated mansion located off an unassuming alley morphs to fit each guest’s desires. To reveal more would spoil the fun, so I’ll just say that I love how Mitchell lulls you into a pretty horrific pattern before springing a couple of major surprises in later chapters. Each time period and narrator feels distinct and believable, and I’m told one character is from two other Mitchell novels (and the phrase “bone clock” even makes an appearance). I need to pick up Cloud Atlas soon for sure. [Public library copy]

This was so cool! I feel like I’d never experienced a “real” Mitchell book before (having only read The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet, which is in some ways the odd one out), and I was impressed by how he brings everything together in this short novel. Every nine years between 1979 and 2015, a different visitor gets sucked into the treacherous world-within-a-world of the Grayer twins’ Slade House. This dilapidated mansion located off an unassuming alley morphs to fit each guest’s desires. To reveal more would spoil the fun, so I’ll just say that I love how Mitchell lulls you into a pretty horrific pattern before springing a couple of major surprises in later chapters. Each time period and narrator feels distinct and believable, and I’m told one character is from two other Mitchell novels (and the phrase “bone clock” even makes an appearance). I need to pick up Cloud Atlas soon for sure. [Public library copy] Dutch artist and writer Barbara Stok’s Vincent is the second graphic novel I’ve read from SelfMadeHero’s

Dutch artist and writer Barbara Stok’s Vincent is the second graphic novel I’ve read from SelfMadeHero’s

Barbara Yelin

Barbara Yelin