Book Serendipity, September through Mid-November

I call it “Book Serendipity” when two or more books that I read at the same time or in quick succession have something in common – the more bizarre, the better. This is a regular feature of mine every couple of months. Because I usually have 20–30 books on the go at once, I suppose I’m more prone to such incidents. People frequently ask how I remember all of these coincidences. The answer is: I jot them down on scraps of paper or input them immediately into a file on my PC desktop; otherwise, they would flit away.

Thanks to Emma and Kay for posting their own Book Serendipity moments! (Liz is always good about mentioning them as she goes along, in the text of her reviews.)

The following are in roughly chronological order.

- An obsession with Judy Garland in My Judy Garland Life by Susie Boyt (no surprise there), which I read back in January, and then again in Beard: A Memoir of a Marriage by Kelly Foster Lundquist.

- Leaving a suicide note hinting at drowning oneself before disappearing in World War II Berlin; and pretending to be Jewish to gain better treatment in Aimée and Jaguar by Erica Fischer and The Lilac People by Milo Todd.

- Leaving one’s clothes on a bank to suggest drowning in The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese, read over the summer, and then Benbecula by Graeme Macrae Burnet.

- A man expecting his wife to ‘save’ him in Amanda by H.S. Cross and Beard: A Memoir of a Marriage by Kelly Foster Lundquist.

A man tells his story of being bullied as a child in Goodbye to Berlin by Christopher Isherwood and Beard by Kelly Foster Lundquist.

A man tells his story of being bullied as a child in Goodbye to Berlin by Christopher Isherwood and Beard by Kelly Foster Lundquist.

- References to Vincent Minnelli and Walt Whitman in a story from Touchy Subjects by Emma Donoghue and Beard by Kelly Foster Lundquist.

- The prospect of having one’s grandparents’ dining table in a tiny city apartment in Beard by Kelly Foster Lundquist and Wreck by Catherine Newman.

- Ezra Pound’s dodgy ideology was an element in The Dime Museum by Joyce Hinnefeld, which I reviewed over the summer, and recurs in Swann by Carol Shields.

- A character has heart palpitations in Andrew Miller’s story from The BBC National Short Story Award 2025 anthology and Endling by Maria Reva.

- A (semi-)nude man sees a worker outside the window and closes the curtains in one story of Cathedral by Raymond Carver and one from Good and Evil and Other Stories by Samanta Schweblin.

- The call of the cuckoo is mentioned in The Edge of Silence by Neil Ansell and Of All that Ends by Günter Grass.

A couple in Italy who have a Fiat in Of All that Ends by Günter Grass and Caoilinn Hughes’s story from The BBC National Short Story Award 2025 anthology.

A couple in Italy who have a Fiat in Of All that Ends by Günter Grass and Caoilinn Hughes’s story from The BBC National Short Story Award 2025 anthology.

- Balzac’s excessive coffee consumption was mentioned in Au Revoir, Tristesse by Viv Groskop, one of my 20 Books of Summer, and then again in The Writer’s Table by Valerie Stivers.

- The main character is rescued from her suicide plan by a madcap idea in The Wedding People by Alison Espach and Endling by Maria Reva.

- The protagonist is taking methotrexate in Sea, Poison by Caren Beilin and Wreck by Catherine Newman.

- A man wears a top hat in Benbecula by Graeme Macrae Burnet and one story of Cathedral by Raymond Carver.

- A man named Angus is the murderer in Benbecula by Graeme Macrae Burnet and Swann by Carol Shields.

The thing most noticed about a woman is a hair on her chin in the story “Pluck” in Touchy Subjects by Emma Donoghue and Swann by Carol Shields.

The thing most noticed about a woman is a hair on her chin in the story “Pluck” in Touchy Subjects by Emma Donoghue and Swann by Carol Shields.

- The female main character makes a point of saying she doesn’t wear a bra in Sea, Poison by Caren Beilin and Find Him! by Elaine Kraf.

- A home hairdressing business in one story of Cathedral by Raymond Carver and Emil & the Detectives by Erich Kästner.

- Painting a bathroom fixture red: a bathtub in The Diary of a Nobody by George Grossmith, one of my 20 Books of Summer; and a toilet in Find Him! by Elaine Kraf.

- A teenager who loses a leg in a road accident in individual stories from A Wild Swan by Michael Cunningham and the Racket anthology (ed. Lisa Moore).

- Digging up the casket of a loved one in the wee hours features in Pet Sematary by Stephen King, one of my 20 Books of Summer; and one story of Pretty Monsters by Kelly Link.

- A character named Dani in the story “The St. Alwynn Girls at Sea” by Sheila Heti and The Silver Book by Olivia Laing; later, author Dani Netherclift (Vessel).

Obsessive cultivation of potatoes in Benbecula by Graeme Macrae Burnet and The Martian by Andy Weir.

Obsessive cultivation of potatoes in Benbecula by Graeme Macrae Burnet and The Martian by Andy Weir.

- The story of Dante Gabriel Rossetti digging up the poems he buried with his love is recounted in Sharon Bala’s story in the Racket anthology (ed. Lisa Moore) and one of the stories in Pretty Monsters by Kelly Link.

- Putting French word labels on objects in Alone in the Classroom by Elizabeth Hay and Find Him! by Elaine Kraf.

A man with part of his finger missing in Find Him! by Elaine Kraf and Lessons from My Teachers by Sarah Ruhl.

A man with part of his finger missing in Find Him! by Elaine Kraf and Lessons from My Teachers by Sarah Ruhl.

- In Minor Black Figures by Brandon Taylor, I came across a mention of the Italian film director Pier Paolo Pasolini, who is a character in The Silver Book by Olivia Laing.

- A character who works in an Ohio hardware store in Flashlight by Susan Choi and Buckeye by Patrick Ryan (two one-word-titled doorstoppers I skimmed from the library). There’s also a family-owned hardware store in Alone in the Classroom by Elizabeth Hay.

- A drowned father – I feel like drownings in general happen much more often in fiction than they do in real life – in The Homecoming by Zoë Apostolides, Flashlight by Susan Choi, and Vessel by Dani Netherclift (as well as multiple drownings in The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese, one of my 20 Books of Summer).

- A memoir by a British man who’s hard of hearing but has resisted wearing hearing aids in the past: first The Quiet Ear by Raymond Antrobus over the summer, then The Edge of Silence by Neil Ansell.

A loved one is given a six-month cancer prognosis but lives another (nearly) two years in All the Way to the River by Elizabeth Gilbert and Lessons from My Teachers by Sarah Ruhl.

A loved one is given a six-month cancer prognosis but lives another (nearly) two years in All the Way to the River by Elizabeth Gilbert and Lessons from My Teachers by Sarah Ruhl.

- A man’s brain tumour is diagnosed by accident while he’s in hospital after an unrelated accident in Flashlight by Susan Choi and Saltwash by Andrew Michael Hurley.

- Famous lost poems in What We Can Know by Ian McEwan and Swann by Carol Shields.

- A description of the anatomy of the ear and how sound vibrates against tiny bones in The Edge of Silence by Neil Ansell and What Stalks the Deep by T. Kingfisher.

- Notes on how to make decadent mashed potatoes in Beard by Kelly Foster Lundquist, Death of an Ordinary Man by Sarah Perry, and Lessons from My Teachers by Sarah Ruhl.

- Transplant surgery on a dog in Russia and trepanning appear in The Heart of a Dog by Mikhail Bulgakov and the poetry collection Common Disaster by M. Cynthia Cheung.

- Audre Lorde, whose Sister Outsider I was reading at the time, is mentioned in Lessons from My Teachers by Sarah Ruhl. Lorde’s line about the master’s tools never dismantling the master’s house is also paraphrased in Spent by Alison Bechdel.

- An adult appears as if fully formed in a man’s apartment but needs to be taught everything, including language and toilet training, in The Heart of a Dog by Mikhail Bulgakov and Find Him! by Elaine Kraf.

Two sisters who each wrote a memoir about their upbringing in Spent by Alison Bechdel and Vessel by Dani Netherclift.

Two sisters who each wrote a memoir about their upbringing in Spent by Alison Bechdel and Vessel by Dani Netherclift.

- The fact that ragwort is bad for horses if it gets mixed up into their feed was mentioned in Ghosts of the Farm by Nicola Chester and Understorey by Anna Chapman Parker.

- The Sylvia Plath line “the O-gape of complete despair” was mentioned in Vessel by Dani Netherclift, then I read it in its original place in Ariel later the same day.

- A mention of the Baba Yaga folk tale (an old woman who lives in the forest in a hut on chicken legs) in Common Disaster by M. Cynthia Cheung and Woman, Eating by Claire Kohda. [There was a copy of Sophie Anderson’s children’s book The House with Chicken Legs in the Little Free Library around that time, too.]

- Coming across a bird that seems to have simply dropped dead in Victorian Psycho by Virginia Feito, Vessel by Dani Netherclift, and Rainforest by Michelle Paver.

- Contemplating a mound of hair in Vessel by Dani Netherclift (at Auschwitz) and Year of the Water Horse by Janice Page (at a hairdresser’s).

- Family members are warned that they should not see the body of their loved one in Vessel by Dani Netherclift and Rainforest by Michelle Paver.

- A father(-in-law)’s swift death from oesophageal cancer in Year of the Water Horse by Janice Page and Death of an Ordinary Man by Sarah Perry.

- I saw John Keats’s concept of negative capability discussed first in My Little Donkey by Martha Cooley and then in Understorey by Anna Chapman Parker.

- I started two books with an Anne Sexton epigraph on the same day: A Portable Shelter by Kirsty Logan and Slags by Emma Jane Unsworth.

- Mentions of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s assassination in Q’s Legacy by Helene Hanff and Sister Outsider for Audre Lorde, both of which I was reading for Novellas in November.

- Mentions of specific incidents from Samuel Pepys’s diary in Q’s Legacy by Helene Hanff and Gin by Shonna Milliken Humphrey, both of which I was reading for Nonfiction November/Novellas in November.

- Starseed (aliens living on earth in human form) in Beautyland by Marie-Helene Bertino and The Conspiracists by Noelle Cook.

- Reading nonfiction by two long-time New Yorker writers at the same time: Life on a Little-Known Planet by Elizabeth Kolbert and Joyride by Susan Orlean.

- The breaking of a mirror seems like a bad omen in The Spare Room by Helen Garner and The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath.

The author’s husband (who has a name beginning with P) is having an affair with a lawyer in Catching Sight by Deni Elliott and Joyride by Susan Orlean.

The author’s husband (who has a name beginning with P) is having an affair with a lawyer in Catching Sight by Deni Elliott and Joyride by Susan Orlean.

- Mentions of Lewis Hyde’s book The Gift in Lessons from My Teachers by Sarah Ruhl and The Serviceberry by Robin Wall Kimmerer; I promptly ordered the Hyde secondhand!

- The protagonist fears being/is accused of trying to steal someone else’s cat in Minka and Curdy by Antonia White and Aunts Aren’t Gentlemen by P.G. Wodehouse, both of which I was reading for Novellas in November.

What’s the weirdest reading coincidence you’ve had lately?

Novellas in November, Week 1: My Year in Novellas (#NovNov23)

Novellas in November begins today! Cathy (746 Books) and I are delighted to be celebrating the art of the short book with you once again. Remember to let us know about your posts here, via the Inlinkz service or through a comment. How impressive is it that before November even started we were already up to 20 blog and social media posts?! I have a feeling this will be a record-breaking year for participation.

I’m kicking off our first weekly prompt:

Week 1 (starts Wednesday 1 November): My Year in Novellas

- During this partial week, tell us about any novellas you have read since last NovNov.

(See the announcement post for more info about the other weeks’ prompts and buddy reads.)

I relish building rather ludicrous stacks of novellas through the year. When I’m standing in front of a Little Free Library, browsing in secondhand bookstores and charity shops, or perusing the shelves at the public library where I volunteer, I’m always thinking about what I could add to my piles for November.

But I do read novella-length books at other times of year, too. Forty-six of them so far this year, according to my Goodreads shelves. That seems impossible, but I guess it reflects the fact that I often choose to review novellas for BookBrowse, Foreword and Shelf Awareness. I’ve read a real mixture, but predominantly literature in translation and autobiographical works. Here are seven highlights:

Fiction

How Strange a Season by Megan Mayhew Bergman: A strong short story collection with the novella-length “Indigo Run” being a Southern Gothic tale of betrayal and revenge.

Loved and Missed by Susie Boyt: The heart-wrenching story of a woman who adopts her granddaughter due to her daughter’s drug addiction. Its brevity speaks emotional volumes.

Crudo by Olivia Laing: A wry, all too relatable take on recent events and our collective hypocrisy and sense of helplessness. Biography + autofiction + cultural commentary.

Nonfiction

Diary of a Tuscan Bookshop by Alba Donati: Lovely snapshots of a bookseller’s personal and professional life.

La Vie: A Year in Rural France by John Lewis-Stempel: A ‘peasant farmer’ chronicles a year in the quest to become self-sufficient. His best book in an age, ideal for armchair travel.

My Neglected Gods by Joanne Nelson: The poignant microessays locate epiphanies in the everyday.

Eggs in Purgatory by Genanne Walsh: A stunning autobiographical essay about the last few months of her father’s life.

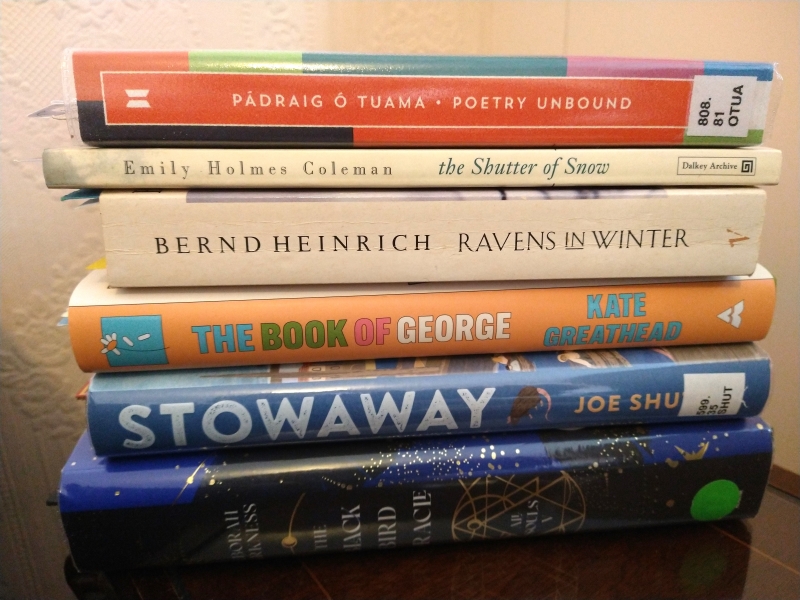

I currently have five novellas underway, and I’ve laid out a pile of potential one-sitting reads for quiet mornings in the weeks to come.

Here’s hoping you all are as excited about short books as I am!

Why not share some recent favourites with us in a post of your own?

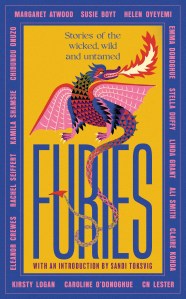

As with any anthology, some pieces stand out more than others. Caroline O’Donoghue, Helen Oyeyemi and Kamila Shamsie’s contributions were unlikely to convert me into a fan. Margaret Atwood is ever sly and accessible, with “Siren” opening with the line “Today’s Liminal Beings Knitting Circle will now be called to order.” I was surprised to get on really well with Kirsty Logan’s “Wench,” about girls ostracized by their religious community because of their desire for each other – I’ll have to read Now She Is Witch, as it’s set in the same fictional world – and Chibundu Onuzo’s “Warrior,” about Deborah, an Israelite leader in the book of Judges. And while I doubt I need to read a whole novel by Rachel Seiffert, I did enjoy “Fury,” about a group of Polish women who fended off Nazi invaders.

As with any anthology, some pieces stand out more than others. Caroline O’Donoghue, Helen Oyeyemi and Kamila Shamsie’s contributions were unlikely to convert me into a fan. Margaret Atwood is ever sly and accessible, with “Siren” opening with the line “Today’s Liminal Beings Knitting Circle will now be called to order.” I was surprised to get on really well with Kirsty Logan’s “Wench,” about girls ostracized by their religious community because of their desire for each other – I’ll have to read Now She Is Witch, as it’s set in the same fictional world – and Chibundu Onuzo’s “Warrior,” about Deborah, an Israelite leader in the book of Judges. And while I doubt I need to read a whole novel by Rachel Seiffert, I did enjoy “Fury,” about a group of Polish women who fended off Nazi invaders. Susanna Jones’s

Susanna Jones’s  The title characters are a brother and sister in their late twenties who share a flat and a tendency to sabotage romantic relationships. Both are matter-of-factly queer and biracial (Māori/Russian). The novel flips back and forth between their present-tense first-person narration with each short chapter. It takes quite a while to pick up on who is who in the extended Vladisavljevic clan and their New Zealand university milieu (their father is a science professor and Greta an English department PhD and tutor), so I was glad of the character list at the start.

The title characters are a brother and sister in their late twenties who share a flat and a tendency to sabotage romantic relationships. Both are matter-of-factly queer and biracial (Māori/Russian). The novel flips back and forth between their present-tense first-person narration with each short chapter. It takes quite a while to pick up on who is who in the extended Vladisavljevic clan and their New Zealand university milieu (their father is a science professor and Greta an English department PhD and tutor), so I was glad of the character list at the start. The Lost Love Songs of Boysie Singh by Ingrid Persaud – I thought Persaud’s debut novel,

The Lost Love Songs of Boysie Singh by Ingrid Persaud – I thought Persaud’s debut novel,