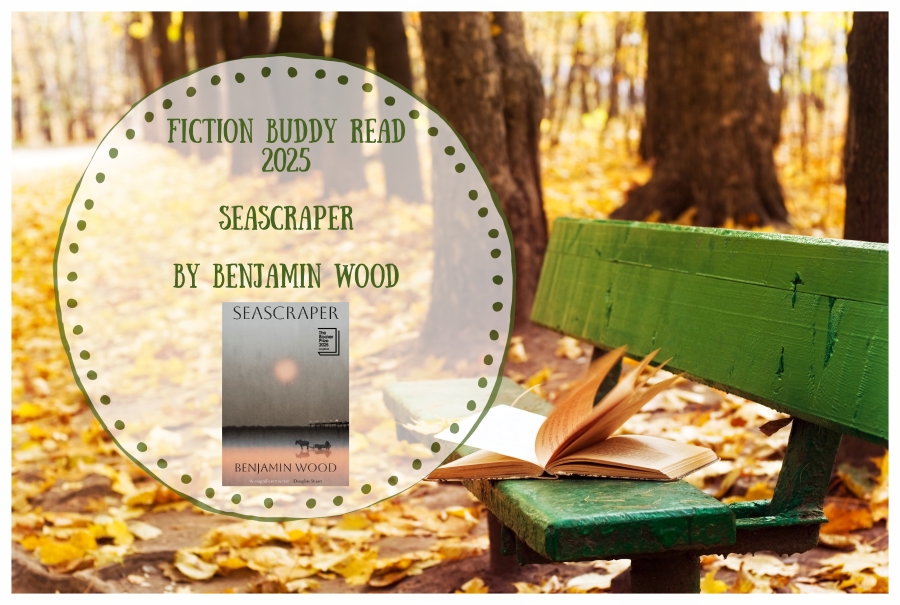

Seascraper by Benjamin Wood (#NovNov25 Buddy Read)

Seascraper is set in what appears to be the early 1960s yet could easily be a century earlier because of the protagonist’s low-tech career. Thomas Flett lives with his mother in fictional Longferry in northwest England and carries on his grandfather’s tradition of fishing with a horse and cart. Each day he trawls the seabed for shrimp – sometimes twice a day when the tide allows – and sells his catch to local restaurants. At around 20 years old, Thomas still lives with his mother, who is disabled by obesity and chronic pain. He’s the sole breadwinner in the household and there’s an unusual dynamic between them in that his mother isn’t all that many years older, having fallen pregnant by a teacher while she was still in school.

Their life is just a mindless trudge of work with cosy patterns of behaviour in between … He wants to wake up every morning with a better purpose.

It’s a humdrum, hardscrabble existence, and Thomas longs for a bigger and more creative life, which he hopes he might achieve through his folk music hobby – or a chance encounter with an American filmmaker. Edgar Acheson is working on a big-screen adaptation of a novel; to save money, it will be filmed here in Merseyside rather than in coastal Maine where it’s set. One day he turns up at the house asking Thomas to be his guide to the sands. Thomas reluctantly agrees to take Edgar out one evening, even though it will mean missing out on an open mic night. They nearly get lost in the fog and the cart starts to sink into quicksand. What follows is mysterious, almost like a hallucination sequence. When Thomas makes it back home safely, he writes an autobiographical song, “Seascraper” (you can listen to a recording on Wood’s website).

After this one pivotal and surprising day, Thomas’s fortunes might just change. This atmospheric novella contrasts subsistence living with creative fulfillment. There is the bitterness of crushed dreams but also a glimmer of hope. Its The Old Man and the Sea-type setup emphasizes questions of solitude, obsession and masculinity. Thomas wishes he had a father in his life; Edgar, even in so short a time frame, acts as a sort of father figure for him. And Edgar is a father himself – he shows Thomas a photo of his daughter. We are invited to ponder what makes a good father and what the absence of one means at different stages in life. Mental and physical health are also crucial considerations for the characters.

That Wood packs all of this into a compact circadian narrative is impressive. My admiration never crossed into warmth, however. I’ve read four of Wood’s five novels and still love his debut, The Bellwether Revivals, most, followed by his second, The Ecliptic. I’ve also read The Young Accomplice, which I didn’t care for as much, so I’m only missing out on A Station on the Path to Somewhere Better now. Wood’s plot and character work is always at a high standard, but his books are so different from each other that I have no clear sense of him as a novelist. Still, I’m pleased that the Booker longlisting has introduced him to many new readers.

Also reviewed by:

Annabel (AnnaBookBel)

Anne (My Head Is Full of Books)

Brona (This Reading Life)

Cathy (746 Books)

Davida (The Chocolate Lady’s Book Review Blog)

Eric (Lonesome Reader)

Jane (Just Reading a Book)

Helen (She Reads Novels)

Kate (Books Are My Favourite and Best)

Kay (What? Me Read?)

Nancy (The Literate Quilter)

Rachel (Yarra Book Club)

Susan (A life in books)

Check out this written interview with Wood (and this video one with Eric of Lonesome Reader) as well as a Q&A on the Booker Prize website in which Wood talks about the unusual situation in which he wrote the book.

(Public library)

[163 pages]

![]()

Most Anticipated Books of the Second Half of 2025

My “Most Anticipated” designation sometimes seems like a kiss of death, but other times the books I choose for these lists live up to my expectations, or surpass them!

(Looking back at the 25 books I selected in January, I see that so far I have read and enjoyed 8, read but been disappointed by 4, not yet read – though they’re on my Kindle or accessible from the library – 9, and not managed to get hold of 4.)

This time around, I’ve chosen 15 books I happen to have heard about that will be released between July and December: 7 fiction and 8 nonfiction. (In release date order within genre. UK release information generally given first, if available. Note given on source if I have managed to get hold of it already.)

Fiction

The Girls Who Grew Big by Leila Mottley [10 July, Fig Tree (Penguin) / June 24, Knopf]: I was impressed with the confident voice in Mottley’s debut, Nightcrawling. She’s just 22 years old so will only keep getting better. This is “about the joys and entanglements of a fierce group of teenage mothers in a small town on the Florida panhandle. … When [16-year-old Adela] tells her parents she’s pregnant, they send her from … Indiana to her grandmother’s in Padua Beach, Florida.” I’ve read one-third so far. (Digital review copy)

The Girls Who Grew Big by Leila Mottley [10 July, Fig Tree (Penguin) / June 24, Knopf]: I was impressed with the confident voice in Mottley’s debut, Nightcrawling. She’s just 22 years old so will only keep getting better. This is “about the joys and entanglements of a fierce group of teenage mothers in a small town on the Florida panhandle. … When [16-year-old Adela] tells her parents she’s pregnant, they send her from … Indiana to her grandmother’s in Padua Beach, Florida.” I’ve read one-third so far. (Digital review copy)

Archive of Unknown Universes by Ruben Reyes Jr. [21 Aug., Footnote Press (Bonnier) / July 1, Mariner Books]: There Is a Rio Grande in Heaven was a strong speculative short story collection and I’m looking forward to his debut novel, which involves alternative history elements. (Starred Kirkus review.) “Cambridge, 2018. Ana and Luis’s relationship is on the rocks, despite their many similarities, including … mothers who both fled El Salvador during the war. In her search for answers, and against her best judgement, Ana uses The Defractor, an experimental device that allows users to peek into alternate versions of their lives.”

Archive of Unknown Universes by Ruben Reyes Jr. [21 Aug., Footnote Press (Bonnier) / July 1, Mariner Books]: There Is a Rio Grande in Heaven was a strong speculative short story collection and I’m looking forward to his debut novel, which involves alternative history elements. (Starred Kirkus review.) “Cambridge, 2018. Ana and Luis’s relationship is on the rocks, despite their many similarities, including … mothers who both fled El Salvador during the war. In her search for answers, and against her best judgement, Ana uses The Defractor, an experimental device that allows users to peek into alternate versions of their lives.”

Minor Black Figures by Brandon Taylor [Oct. 7, Riverhead / 5 March 2026, Jonathan Cape (Penguin)]: I’ve read all of his works … but I’m so glad he’s moving past campus settings now. “A newcomer to New York, Wyeth is a Black painter who grew up in the South and is trying to find his place in the contemporary Manhattan art scene. … When he meets Keating, a white former seminarian who left the priesthood, Wyeth begins to reconsider how to observe the world, in the process facing questions about the conflicts between Black and white art, the white gaze on the Black body, and the compromises we make – in art and in life.” (Edelweiss download)

Minor Black Figures by Brandon Taylor [Oct. 7, Riverhead / 5 March 2026, Jonathan Cape (Penguin)]: I’ve read all of his works … but I’m so glad he’s moving past campus settings now. “A newcomer to New York, Wyeth is a Black painter who grew up in the South and is trying to find his place in the contemporary Manhattan art scene. … When he meets Keating, a white former seminarian who left the priesthood, Wyeth begins to reconsider how to observe the world, in the process facing questions about the conflicts between Black and white art, the white gaze on the Black body, and the compromises we make – in art and in life.” (Edelweiss download)

Heart the Lover by Lily King [16 Oct., Canongate / Oct. 7, Grove Press]: I’ve read several of her books and after Writers & Lovers I’m a forever fan. “In the fall of her senior year of college, [Jordan] meets two star students from her 17th-Century Lit class, Sam and Yash. … she quickly discovers the pleasures of friendship, love and her own intellectual ambition. … when a surprise visit and unexpected news brings the past crashing into the present, Jordan returns to a world she left behind and is forced to confront the decisions and deceptions of her younger self.” (Edelweiss download)

Heart the Lover by Lily King [16 Oct., Canongate / Oct. 7, Grove Press]: I’ve read several of her books and after Writers & Lovers I’m a forever fan. “In the fall of her senior year of college, [Jordan] meets two star students from her 17th-Century Lit class, Sam and Yash. … she quickly discovers the pleasures of friendship, love and her own intellectual ambition. … when a surprise visit and unexpected news brings the past crashing into the present, Jordan returns to a world she left behind and is forced to confront the decisions and deceptions of her younger self.” (Edelweiss download)

Wreck by Catherine Newman [28 Oct., Transworld / Harper]: This is a sequel to Sandwich, and in general sequels should not exist. However, I can make a rare exception. Set two years on, this finds “Rocky, still anxious, nostalgic, and funny, obsessed with a local accident that only tangentially affects them—and with a medical condition that, she hopes, won’t affect them at all.” In a recent Substack post, Newman compared it to Small Rain, my book of 2024, for the focus on a mystery medical condition. (Edelweiss download)

Wreck by Catherine Newman [28 Oct., Transworld / Harper]: This is a sequel to Sandwich, and in general sequels should not exist. However, I can make a rare exception. Set two years on, this finds “Rocky, still anxious, nostalgic, and funny, obsessed with a local accident that only tangentially affects them—and with a medical condition that, she hopes, won’t affect them at all.” In a recent Substack post, Newman compared it to Small Rain, my book of 2024, for the focus on a mystery medical condition. (Edelweiss download)

Palaver by Bryan Washington [Nov. 4, Farrar, Straus, and Giroux / 1 Jan. 2026, Atlantic]: I’ve read all his work and I’m definitely a fan, though I wish that (like Taylor previously) he wouldn’t keep combining the same elements each time. I’ll be reviewing this early for Shelf Awareness; hooray that I don’t have to wait until 2026! “He’s entangled in a sexual relationship with a married man, and while he has built a chosen family in Japan, he is estranged from his family in Houston, particularly his mother … Then, in the weeks leading up to Christmas, ten years since they’ve last seen each other, the mother arrives uninvited on his doorstep. Separated only by the son’s cat, Taro, the two of them bristle against each other immediately.” (Edelweiss download)

Palaver by Bryan Washington [Nov. 4, Farrar, Straus, and Giroux / 1 Jan. 2026, Atlantic]: I’ve read all his work and I’m definitely a fan, though I wish that (like Taylor previously) he wouldn’t keep combining the same elements each time. I’ll be reviewing this early for Shelf Awareness; hooray that I don’t have to wait until 2026! “He’s entangled in a sexual relationship with a married man, and while he has built a chosen family in Japan, he is estranged from his family in Houston, particularly his mother … Then, in the weeks leading up to Christmas, ten years since they’ve last seen each other, the mother arrives uninvited on his doorstep. Separated only by the son’s cat, Taro, the two of them bristle against each other immediately.” (Edelweiss download)

The Silver Book by Olivia Laing [6 Nov., Hamish Hamilton (Penguin) / 11 Nov., Farrar, Straus and Giroux]: I’ve read all but one of Laing’s books and consider her one of our most important contemporary thinkers. I was also pleasantly surprised by Crudo so will be reading this second novel, too. I’ll be reviewing it early for Shelf Awareness as well. “September 1974. Two men meet by chance in Venice. One is a young English artist, in panicked flight from London. The other is Danilo Donati, the magician of Italian cinema. … The Silver Book is at once a queer love story and a noirish thriller, set in the dream factory of cinema. (Edelweiss download)

The Silver Book by Olivia Laing [6 Nov., Hamish Hamilton (Penguin) / 11 Nov., Farrar, Straus and Giroux]: I’ve read all but one of Laing’s books and consider her one of our most important contemporary thinkers. I was also pleasantly surprised by Crudo so will be reading this second novel, too. I’ll be reviewing it early for Shelf Awareness as well. “September 1974. Two men meet by chance in Venice. One is a young English artist, in panicked flight from London. The other is Danilo Donati, the magician of Italian cinema. … The Silver Book is at once a queer love story and a noirish thriller, set in the dream factory of cinema. (Edelweiss download)

Nonfiction

Jesusland: Stories from the Upside[-]Down World of Christian Pop Culture by Joelle Kidd [Aug. 12, ECW]: “Through nine incisive, honest, and emotional essays, Jesusland exposes the pop cultural machinations of evangelicalism, while giving voice to aughts-era Christian children and teens who are now adults looking back at their time measuring the length of their skirts … exploring the pop culture that both reflected and shaped an entire generation of young people.” Yep, that includes me! Looking forward to a mixture of Y2K and Jesus Freak. (NetGalley download)

Jesusland: Stories from the Upside[-]Down World of Christian Pop Culture by Joelle Kidd [Aug. 12, ECW]: “Through nine incisive, honest, and emotional essays, Jesusland exposes the pop cultural machinations of evangelicalism, while giving voice to aughts-era Christian children and teens who are now adults looking back at their time measuring the length of their skirts … exploring the pop culture that both reflected and shaped an entire generation of young people.” Yep, that includes me! Looking forward to a mixture of Y2K and Jesus Freak. (NetGalley download)

Somebody Is Walking on Your Grave: My Cemetery Journeys by Mariana Enríquez; translated from Spanish by Megan McDowell [25 Sept., Granta / Sept. 30, Hogarth]: I’ve enjoyed her creepy short stories, plus I love touring graveyards. “In 2013, when the body of a friend’s mother who was disappeared during Argentina’s military dictatorship was found in a common grave, she began to examine more deeply the complex meanings of cemeteries and where our bodies come to rest. In this vivid, cinematic book … Enriquez travels North and South America, Europe and Australia … [and] investigates each cemetery’s history, architecture, its dead (famous and not), its saints and ghosts, its caretakers and visitors.” (Edelweiss download, for Shelf Awareness review)

Somebody Is Walking on Your Grave: My Cemetery Journeys by Mariana Enríquez; translated from Spanish by Megan McDowell [25 Sept., Granta / Sept. 30, Hogarth]: I’ve enjoyed her creepy short stories, plus I love touring graveyards. “In 2013, when the body of a friend’s mother who was disappeared during Argentina’s military dictatorship was found in a common grave, she began to examine more deeply the complex meanings of cemeteries and where our bodies come to rest. In this vivid, cinematic book … Enriquez travels North and South America, Europe and Australia … [and] investigates each cemetery’s history, architecture, its dead (famous and not), its saints and ghosts, its caretakers and visitors.” (Edelweiss download, for Shelf Awareness review)

Ghosts of the Farm: Two Women’s Journeys Through Time, Land and Community by Nicola Chester [30 Sept., Chelsea Green]: Nicola is our local nature writer and is so wise on class and countryside matters. On Gallows Down was her wonderful debut and, though I know very little about it, I’m looking forward to her second book. “This is the story of Miss White, a woman who lived in the author’s village 80 years ago, a pioneer who realised her ambition to become a farmer during the Second World War. … Moving between Nicola’s own attempts to work outdoors and Miss White’s desire to farm a generation earlier, Nicola explores the parallels between their lives – and the differences.”

Ghosts of the Farm: Two Women’s Journeys Through Time, Land and Community by Nicola Chester [30 Sept., Chelsea Green]: Nicola is our local nature writer and is so wise on class and countryside matters. On Gallows Down was her wonderful debut and, though I know very little about it, I’m looking forward to her second book. “This is the story of Miss White, a woman who lived in the author’s village 80 years ago, a pioneer who realised her ambition to become a farmer during the Second World War. … Moving between Nicola’s own attempts to work outdoors and Miss White’s desire to farm a generation earlier, Nicola explores the parallels between their lives – and the differences.”

Death of an Ordinary Man by Sarah Perry [2 Oct., Vintage (Penguin)]: I’ve had a very mixed experience with Perry’s fiction, but a short bereavement memoir should be right up my street. “Sarah Perry’s father-in-law, David, died at home nine days after a cancer diagnosis and having previously been in the good health. The speed of his illness outstripped that of the NHS and social care, so the majority of nursing fell to Sarah and her husband. They witnessed what happens to the body and spirit, hour by hour, as it approaches death.”

Death of an Ordinary Man by Sarah Perry [2 Oct., Vintage (Penguin)]: I’ve had a very mixed experience with Perry’s fiction, but a short bereavement memoir should be right up my street. “Sarah Perry’s father-in-law, David, died at home nine days after a cancer diagnosis and having previously been in the good health. The speed of his illness outstripped that of the NHS and social care, so the majority of nursing fell to Sarah and her husband. They witnessed what happens to the body and spirit, hour by hour, as it approaches death.”

Book of Lives: A Memoir of Sorts by Margaret Atwood [4 Nov., Vintage (Penguin) / Doubleday]: It’s Atwood; ’nuff said, though I admit I’m daunted by the page count. “Raised by ruggedly independent, scientifically minded parents – entomologist father, dietician mother – Atwood spent most of each year in the wild forest of northern Quebec. … [She links] seminal moments to the books that have shaped our literary landscape. … In pages bursting with bohemian gatherings … and major political turning points, we meet poets, bears, Hollywood actors and larger-than-life characters straight from the pages of an Atwood novel.”

Book of Lives: A Memoir of Sorts by Margaret Atwood [4 Nov., Vintage (Penguin) / Doubleday]: It’s Atwood; ’nuff said, though I admit I’m daunted by the page count. “Raised by ruggedly independent, scientifically minded parents – entomologist father, dietician mother – Atwood spent most of each year in the wild forest of northern Quebec. … [She links] seminal moments to the books that have shaped our literary landscape. … In pages bursting with bohemian gatherings … and major political turning points, we meet poets, bears, Hollywood actors and larger-than-life characters straight from the pages of an Atwood novel.”

Tigers Between Empires: The Improbable Return of Great Cats to the Forests of Russia and China by Jonathan C. Slaght [4 Nov., Allen Lane / Farrar, Straus and Giroux]: Slaght’s Owls of the Eastern Ice was one of the best books I read in 2022; he’s a top-notch nature and travel writer with an environmentalist’s conscience. After the fall of the Soviet Union, “scientists came together to found the Siberian Tiger Project[, which …] captured and released more than 114 tigers over three decades. … [C]haracters, both feline and human, come fully alive as we travel with them through the quiet and changing forests of Amur.” (NetGalley download)

Tigers Between Empires: The Improbable Return of Great Cats to the Forests of Russia and China by Jonathan C. Slaght [4 Nov., Allen Lane / Farrar, Straus and Giroux]: Slaght’s Owls of the Eastern Ice was one of the best books I read in 2022; he’s a top-notch nature and travel writer with an environmentalist’s conscience. After the fall of the Soviet Union, “scientists came together to found the Siberian Tiger Project[, which …] captured and released more than 114 tigers over three decades. … [C]haracters, both feline and human, come fully alive as we travel with them through the quiet and changing forests of Amur.” (NetGalley download)

Joyride by Susan Orlean [6 Nov., Atlantic Books / Oct. 14, Avid Reader Press (Simon & Schuster)]: I’m a fan of Orlean’s genre-busting nonfiction, e.g. The Orchid Thief and The Library Book, and have always wanted to try more by her. “Joyride is her most personal book ever—a searching journey through finding her feet as a journalist, recovering from the excruciating collapse of her first marriage, falling head-over-heels in love again, becoming a mother while mourning the decline of her own mother, sojourning to Hollywood for films based on her work. … Joyride is also a time machine to a bygone era of journalism.”

Joyride by Susan Orlean [6 Nov., Atlantic Books / Oct. 14, Avid Reader Press (Simon & Schuster)]: I’m a fan of Orlean’s genre-busting nonfiction, e.g. The Orchid Thief and The Library Book, and have always wanted to try more by her. “Joyride is her most personal book ever—a searching journey through finding her feet as a journalist, recovering from the excruciating collapse of her first marriage, falling head-over-heels in love again, becoming a mother while mourning the decline of her own mother, sojourning to Hollywood for films based on her work. … Joyride is also a time machine to a bygone era of journalism.”

A Long Game: Notes on Writing Fiction by Elizabeth McCracken [Dec. 2, Ecco]: I’m not big on craft books, but will occasionally read one by an author I admire; McCracken won my heart with The Hero of This Book. “How does one face the blank page? Move a character around a room? Deal with time? Undertake revision? The good and bad news is that in fiction writing, there are no definitive answers. … McCracken … has been teaching for more than thirty-five years [… and] shares insights gleaned along the way, offering practical tips and incisive thoughts about her own work as an artist.” (Edelweiss download)

A Long Game: Notes on Writing Fiction by Elizabeth McCracken [Dec. 2, Ecco]: I’m not big on craft books, but will occasionally read one by an author I admire; McCracken won my heart with The Hero of This Book. “How does one face the blank page? Move a character around a room? Deal with time? Undertake revision? The good and bad news is that in fiction writing, there are no definitive answers. … McCracken … has been teaching for more than thirty-five years [… and] shares insights gleaned along the way, offering practical tips and incisive thoughts about her own work as an artist.” (Edelweiss download)

As a bonus, here are two advanced releases that I reviewed early:

Trying: A Memoir by Chloe Caldwell [Aug. 5, Graywolf] (Reviewed for Foreword): Caldwell devoted much of her thirties to trying to get pregnant via intrauterine insemination. She developed rituals to ease the grueling routine: After every visit, she made a stop for luxury foodstuffs and beauty products. But then her marriage imploded. When she began dating women and her determination to become a mother persisted, a new conception strategy was needed. The book’s fragmentary style suits its aura of uncertainty about the future. Sparse pages host a few sentences or paragraphs, interspersed with wry lists.

Trying: A Memoir by Chloe Caldwell [Aug. 5, Graywolf] (Reviewed for Foreword): Caldwell devoted much of her thirties to trying to get pregnant via intrauterine insemination. She developed rituals to ease the grueling routine: After every visit, she made a stop for luxury foodstuffs and beauty products. But then her marriage imploded. When she began dating women and her determination to become a mother persisted, a new conception strategy was needed. The book’s fragmentary style suits its aura of uncertainty about the future. Sparse pages host a few sentences or paragraphs, interspersed with wry lists. ![]()

If You Love It, Let It Kill You by Hannah Pittard [July 15, Henry Holt] (Reviewed for Shelf Awareness): A quirky work of autofiction about an author/professor tested by her ex-husband’s success, her codependent family, and an encounter with a talking cat. Hana P. (or should that be Pittard?) relishes flouting the “rules” of creative writing. With her affectations and unreliability, she can be a frustrating narrator, but the metafictional angle renders her more wily than precious. The dialogue and scenes sparkle, and there are delightful characters This gleefully odd book is perfect for Miranda July and Patricia Lockwood fans.

If You Love It, Let It Kill You by Hannah Pittard [July 15, Henry Holt] (Reviewed for Shelf Awareness): A quirky work of autofiction about an author/professor tested by her ex-husband’s success, her codependent family, and an encounter with a talking cat. Hana P. (or should that be Pittard?) relishes flouting the “rules” of creative writing. With her affectations and unreliability, she can be a frustrating narrator, but the metafictional angle renders her more wily than precious. The dialogue and scenes sparkle, and there are delightful characters This gleefully odd book is perfect for Miranda July and Patricia Lockwood fans. ![]()

I can also recommend:

Both/And: Essays by Trans and Gender-Nonconforming Writers of Color, ed. Denne Michele Norris [Aug. 12, HarperOne / 25 Sept., HarperCollins] (Review to come for Shelf Awareness) ![]()

Other People’s Mothers by Julie Marie Wade [Sept. 2, Univ. of Florida Press] (Review pending for Foreword) ![]()

Which of these catch your eye? Any other books you’re looking forward to in this second half of the year?

Spring Reads, Part II: Blossomise, Spring Chicken & Cold Spring Harbor

Our garden is an unruly assortment of wildflowers, rosebushes, fruit trees and hedge plants, along with an in-progress pond, and we’ve made a few half-hearted attempts at planting vegetable seeds and flower bulbs. It felt more like summer earlier in May, before we left for France; as the rest of the spring plays out, we’ll see if the beetroot, courgettes, radishes and tomatoes amount to anything. The gladioli have certainly been shooting for the sky!

I recently encountered spring (if only in name) through these three books, a truly mixed bag: a novelty poetry book memorable more for the illustrations than for the words, a fascinating popular account of the science of ageing, and a typically depressing (if you know the author, anyway) novel about failing marriages and families. Part I of my Spring Reading was here.

Blossomise by Simon Armitage; illus. Angela Harding (2024)

Armitage has been the Poet Laureate for yonks now, but I can’t say his poetry has ever made much of an impression on me. That’s especially true of this slim volume commissioned by the National Trust: it’s 3 stars for Angela Harding’s lovely if biologically inaccurate (but I’ll be kind and call them whimsical) engravings, and 2 stars for the actual poems, which are light on content. Plum, cherry, apple, pear, blackthorn and hawthorn blossom loom large. It’s hard to describe spring without resorting to enraptured clichés, though: “Planet Earth in party mode, / petals fizzing and frothing / like pink champagne.” The haiku (11 of 21 poems) feel particularly tossed-off: “The streets are learning / the language of plum blossom. / The trees have spoken.” But others are sure to think more of this than I did.

Armitage has been the Poet Laureate for yonks now, but I can’t say his poetry has ever made much of an impression on me. That’s especially true of this slim volume commissioned by the National Trust: it’s 3 stars for Angela Harding’s lovely if biologically inaccurate (but I’ll be kind and call them whimsical) engravings, and 2 stars for the actual poems, which are light on content. Plum, cherry, apple, pear, blackthorn and hawthorn blossom loom large. It’s hard to describe spring without resorting to enraptured clichés, though: “Planet Earth in party mode, / petals fizzing and frothing / like pink champagne.” The haiku (11 of 21 poems) feel particularly tossed-off: “The streets are learning / the language of plum blossom. / The trees have spoken.” But others are sure to think more of this than I did.

A favourite passage: “Scented and powdered / she’s staging / a one-tree show / with hi-viz blossoms / and lip-gloss petals; / she’ll season the pavements / and polished stones / with something like snow.” (Public library) ![]()

Spring Chicken: Stay Young Forever (or Die Trying) by Bill Gifford (2015)

Gifford was in his mid-forties when he undertook this quirky journey into the science and superstitions of ageing. As a starting point, he ponders the differences between his grandfather, who swam and worked his orchard until his death from infection at 86, and his great-uncle, not so different in age, who developed Alzheimer’s and died in a nursing home at 74. Why is the course of ageing so different for different people? Gifford suspects that, in this case, it had something to do with Uncle Emerson’s adherence to the family tradition of Christian Science and refusal to go to the doctor for any medical concern. (An alarming fact: “The Baby Boom generation is the first in centuries that has actually turned out to be less healthy than their parents, thanks largely to diabetes, poor diet, and general physical laziness.”) But variation in healthspan is still something of a mystery.

Gifford was in his mid-forties when he undertook this quirky journey into the science and superstitions of ageing. As a starting point, he ponders the differences between his grandfather, who swam and worked his orchard until his death from infection at 86, and his great-uncle, not so different in age, who developed Alzheimer’s and died in a nursing home at 74. Why is the course of ageing so different for different people? Gifford suspects that, in this case, it had something to do with Uncle Emerson’s adherence to the family tradition of Christian Science and refusal to go to the doctor for any medical concern. (An alarming fact: “The Baby Boom generation is the first in centuries that has actually turned out to be less healthy than their parents, thanks largely to diabetes, poor diet, and general physical laziness.”) But variation in healthspan is still something of a mystery.

Over the course of the book, Gifford meets all number of researchers and cranks as he attends conferences, travels to spend time with centenarians and scientists, and participates in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. There have been some truly zany ideas about how to pause or reverse aging, such as self-dosing with hormones (Suzanne Somers is one proponent), but long-term use is discouraged. Some things that do help, to an extent, are calorie restriction and periodic fasting plus, possibly, red wine, coffee and aspirin. But the basic advice is nothing we don’t already know about health: don’t eat too much and exercise, i.e., avoid obesity. The layman-interpreting-science approach reminded me of Mary Roach’s. There was some crossover in content with Mark O’Connell’s To Be a Machine and various books I’ve read about dementia. Fun and enlightening. (New purchase – bargain book from Dollar Tree, Bowie, MD) ![]()

Cold Spring Harbor by Richard Yates (1986)

Cold Spring Harbor is a Long Island hamlet whose name casts an appropriately chilly shadow over this slim novel about families blighted by alcoholism and poor decisions. Evan Shepard, only in his early twenties, already has a broken marriage behind him after a teenage romance led to an unplanned pregnancy. Mary and their daughter Kathleen seem to be in the rearview mirror as he plans to return to college for an engineering degree. One day he accompanies his father into New York City for an eye doctor appointment and the car breaks down. The men knock on a random door and thereby become entwined with the Drakes: Gloria, the unstable, daytime-drinking mother; Rachel, her beautiful daughter; and Phil, her earnest but unconfident adolescent son.

Cold Spring Harbor is a Long Island hamlet whose name casts an appropriately chilly shadow over this slim novel about families blighted by alcoholism and poor decisions. Evan Shepard, only in his early twenties, already has a broken marriage behind him after a teenage romance led to an unplanned pregnancy. Mary and their daughter Kathleen seem to be in the rearview mirror as he plans to return to college for an engineering degree. One day he accompanies his father into New York City for an eye doctor appointment and the car breaks down. The men knock on a random door and thereby become entwined with the Drakes: Gloria, the unstable, daytime-drinking mother; Rachel, her beautiful daughter; and Phil, her earnest but unconfident adolescent son.

Evan and Rachel soon marry and agree to Gloria’s plan of sharing a house in Cold Spring Harbor, where the Shepards live (Evan’s mother is also an alcoholic, but less functional; she hides behind the “invalid” label). Take it from me: living with your in-laws is never a good idea! As the Second World War looms, and with Evan and Rachel expecting a baby, it’s clear something will have to give with this uneasy family arrangement, but the dramatic break I was expecting – along the lines of a death or accident – never arrived. Instead, there’s just additional slow crumbling, and the promise of greater suffering to come. Although Yates’s character portraits are as penetrating as in Easter Parade, I found the plot a little lacklustre here. (Secondhand – Clutterbooks, Sedbergh) ![]()

Any ‘spring’ reads for you recently?

Reviewing Two Books by Cancelled Authors

I don’t have anything especially insightful to say about these authors’ reasons for being cancelled, although in my review of the Clanchy I’ve noted the textual examples that have been cited as problematic. Alexie is among the legion of male public figures to have been accused of sexual misconduct in recent years. I’m not saying those aren’t serious allegations, but as Claire Dederer wrestled with in Monsters, our judgement of a person can be separate from our response to their work. So that’s the good news: I thought these were both fantastic books. They share a theme of education.

The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie (illus. Ellen Forney) (2007)

Alexie is to be lauded for his contributions to the flourishing of both Indigenous literature and YA literature. This was my first of his books and I don’t know a thing about him or the rest of his work. But I feel like this must have groundbreaking for its time (or maybe a throwback to Adrian Mole et al.), and I suspect it’s more than a little autobiographical.

Alexie is to be lauded for his contributions to the flourishing of both Indigenous literature and YA literature. This was my first of his books and I don’t know a thing about him or the rest of his work. But I feel like this must have groundbreaking for its time (or maybe a throwback to Adrian Mole et al.), and I suspect it’s more than a little autobiographical.

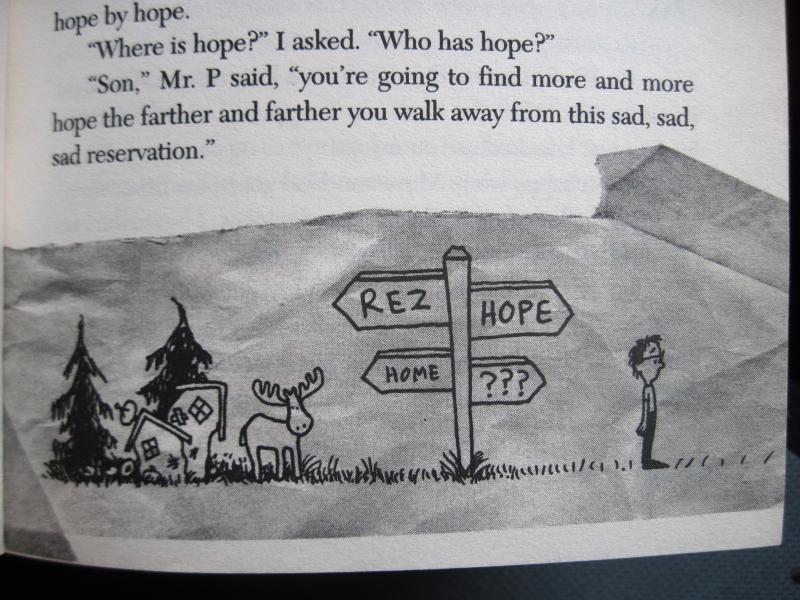

It reads exactly like a horny 14-year-old boy’s diary, but “Junior” (Arnold Spirit, Jr.) is also self-deprecating and sweetly vulnerable; Alexie’s tone is spot on. Junior has had a tough life on a Spokane reservation in Washington, being bullied for his poor eyesight and speech impediments that resulted from brain damage at birth and ongoing seizures. Poverty, alcoholism, casinos: they don’t feel like clichés of Indian reservations here because Alexie writes from experience and presents them matter-of-factly. Junior’s parents never got to pursue their dreams and his sister has run away to Montana, but he has a chance to change the trajectory. A rez teacher says his only hope for a bright future is to transfer to the elite high school in Reardan. So he does, even though it often requires hitch-hiking or walking miles.

Junior soon becomes adept at code-switching: “Traveling between Reardan and Wellpinit, between the little white town and the reservation, I always felt like a stranger. I was half Indian in one place and half white in the other.” He gets a white girlfriend, Penelope, but has to work hard to conceal how impoverished he is. His best friend, Rowdy, is furious with him for abandoning his people. That resentment builds all the way to a climactic basketball match between Reardan and Wellpinit that also functions as a symbolic battle between the parts of Junior’s identity. Along the way, there are multiple tragic deaths in which alcohol, inevitably, plays a role. “I’m fourteen years old and I’ve been to forty-two funerals,” he confides. “Jeez, what a sucky life. … I kept trying to find the little pieces of joy in my life. That’s the only way I managed to make it through all of that death and change.”

One of those joys, for him, is cartooning. Describing his cartoons to his new white friend, Gordy, he says, “I use them to understand the world.”

Forney’s black-and-white illustrations make the cartoons look like found objects – creased scraps of notebook paper sellotaped into a diary. This isn’t a graphic novel, but most of the short chapters include several illustrations. There’s a casual intimacy to the whole book that feels absolutely authentic. Bridging the particular and universal, it’s a heartfelt gem, and not just for teens. (University library) ![]()

Some Kids I Taught and What They Taught Me by Kate Clanchy (2019)

If your Twitter sphere and mine overlap, you may remember the controversy over the racialized descriptions in this Orwell Prize-winning memoir of 30 years of teaching – and the fact that, rather than issuing a humbled apology, Clanchy, at least initially, doubled down and refuted all objections, even when they came from BIPOC. It wasn’t a good look. Nor was it the first time I’ve found Clanchy to be prickly. (She is what, in another time, might have been called a formidable woman.) Anyway, I waited a few years for the furore to die down before trying this for myself.

I know vanishingly little about the British education system because I don’t have children and only experienced uni here at a distance, through my junior year abroad. So there may be class-based nuances I missed – for instance, in the chapter about selecting a school for her oldest son and comparing it with the underprivileged Essex school where she taught. But it’s clear that a lot of her students posed serious challenges. Many were refugees or immigrants, and she worked for a time on an “Inclusion Unit,” which seems to be more in the business of exclusion in that it’s for students who have been removed from regular classrooms. They came from bad family situations and were more likely to end up in prison or pregnant. To get any of them to connect with Shakespeare, or write their own poetry, was a minor miracle.

Clanchy is also a poet and novelist – I’ve read one of her novels, and her Selected Poems – and did much to encourage her students to develop a voice and the confidence to have their work published (she’s produced anthologies of student work). In many cases, she gave them strategies for giving literary shape to traumatic memories. The book’s engaging vignettes have all had the identifying details removed, and are collected under thematic headings that address the second part of the title: “About Love, Sex, and the Limits of Embarrassment” and “About Nations, Papers, and Where We Belong” are two example chapters. She doesn’t avoid contentious topics, either: the hijab, religion, mental illness and so on.

You get the feeling that she was a friend and mentor to her students, not just their teacher, and that they could talk to her about anything and rely on her support. Watching them grow in self-expression is heart-warming; we come to care for these young people, too, because of how sincerely they have been created from amalgams. Indeed, Clanchy writes in the introduction that “I have included nobody, teacher or pupil, about whom I could not write with love.”

And that is, I think, why she was so hurt and disbelieving when people pointed out racism in her characterization:

I was baffled when a boy with jet-black hair and eyes and a fine Ashkenazi nose named David Marks refused any Jewish heritage

her furry eyebrows, her slanting, sparking black eyes, her general, Mongolian ferocity. [but she’s Afghan??]

(of girls in hijabs) I never saw their (Asian/silky/curly?) hair in eight years.

They’re a funny pair: Izzat so small and square and Afghan with his big nose and premature moustache; Mo so rounded and mellow and Pakistani with his long-lashed eyes and soft glossy hair.

There are a few other ill-advised passages. She admits she can’t tell the difference between Kenyan and Somali faces; she ponders whether being a Scot in England gave her some taste of the prejudice refugees experience. And there’s this passage about sexuality:

Are we all ‘fluid’ now? Perhaps. It is commonplace to proclaim oneself transsexual. And to actually be gay, especially if you are as pretty as Kristen Stewart, is positively fashionable. A couple of kids have even changed gender, a decision … deliciously of the moment

My take: Clanchy wanted to craft affectionate pen portraits that celebrated children’s uniqueness, but had to make them anonymous, so resorted to generalizations. Doing this on a country or ethnicity basis was the mistake. Journalistic realism doesn’t require a focus on appearances (I would hope that, if I were ever profiled, someone could find more interesting things to say about me than that I am short and have a large nose). She could have just introduced the students with ‘facts,’ e.g., “Shakila, from Afghanistan, wore a hijab and was feisty and outspoken.” Note to self: white people can be clueless, and we need to listen and learn. The book was reissued in 2022 by independent publisher Swift Press, with offending passages removed (see here for more info). I’d be keen to see the result and hope that the book will find more readers because, truly, it is lovely. (Little Free Library) ![]()

Easter Reading: The Five Wounds by Kirstin Valdez Quade

The Holy Week opening was the excuse I needed to pick up this review copy from 2021. Amadeo Padilla is playing Jesus this year in the Las Penas, New Mexico penitentes’ reenactment of the crucifixion. At 33, he’s the perfect age for the role; no matter that he’s an unemployed alcoholic and a single father to 15-year-old Angel, who is pregnant. Looping from one Good Friday to the next, this debut novel is a crushingly honest look at family dynamics. It’s what isn’t said that might tear them apart: Amadeo’s mother, Yolanda, hasn’t told anyone about her diagnosis, and Amadeo conveniently covers up the fact that he’s sleeping with Brianna, Angel’s teacher at the Smart Starts! high school equivalency program.

The Holy Week opening was the excuse I needed to pick up this review copy from 2021. Amadeo Padilla is playing Jesus this year in the Las Penas, New Mexico penitentes’ reenactment of the crucifixion. At 33, he’s the perfect age for the role; no matter that he’s an unemployed alcoholic and a single father to 15-year-old Angel, who is pregnant. Looping from one Good Friday to the next, this debut novel is a crushingly honest look at family dynamics. It’s what isn’t said that might tear them apart: Amadeo’s mother, Yolanda, hasn’t told anyone about her diagnosis, and Amadeo conveniently covers up the fact that he’s sleeping with Brianna, Angel’s teacher at the Smart Starts! high school equivalency program.

The title refers to the stigmata of Christ, but could just as well apply to the Padillas’ five generations, from baby Connor all the way up to Tío Tíve, Amadeo’s great-uncle. Substance abuse, poverty and abandonment are generational wounds that run through this family. Quade treats heavy subjects and damaged characters with kindness, never mocking or descending into cruelty. There is even levity to failures like Amadeo’s windshield crack repair venture. Any of these characters could have been caricatures, especially Angel as a teen mother, but Quade gives them depth. Angel’s emulation of Brianna and her classmate Lizette, her grudging care for Connor and Yolanda, and her ambivalent feelings towards Ryan, Connor’s father, are just a few of the aspects that make her a plucky, winsome protagonist.

The inclusion of Lent and Advent sets up the book’s emotional palette: waiting, guilt, self-sacrifice; preparing for birth, death and the determination to forge a new life. It’s refreshing, however, that the theological content is not just metaphorical here; these characters have a staunch Catholic background, and they take seriously Jesus’ example:

Good Friday was supposed to save Amadeo. He was supposed to be past the shame and failure and the mistakes that hardly seem to be his own and that unravel beyond his control. Amadeo feels cheated. By Passion week, by the penitentes, by Jesus himself. The fact is that no one can be crucified every day—not even Jesus could pull off that miracle.

Amadeo asks himself, with no trace of irony, what Jesus would do in the kinds of situations he finds himself in.

I would have liked more closure about two secondary characters, and at over 400 pages of small type, The Five Wounds is on the overlong side. But it’s so strong on characters and scenes, from classroom to hospital, that my interest never waned. Different as their settings are, I’d liken this to An American Marriage by Tayari Jones and Love After Love by Ingrid Persaud – two novels that had me aching for their vibrant characters’ poor decisions compounded by bad luck. The authors’ compassionate outlook makes the tragic elements bearable. I’ll be catching up on Quade’s first book, the short story collection Night at the Fiestas, as soon as I can.

With thanks to Profile Books (Tuskar Rock imprint) for the free copy for review.

Bonuses:

I recently finished a limping reread of Watership Down by Richard Adams. This was my favourite book as a child, but I couldn’t recapture the magic in my late thirties. The novelty this time around was in being able to recognize all the settings – the rabbits’ epic quest takes place on the outskirts of Newbury; we’ve walked through its countryside locations. (In fact, my husband, in his capacity as a town councillor, has testified at a hearing in objection to a plan to build 1000 houses at Sandleford, where the rabbits set out from.) I can see why I loved this at age nine: anthropomorphized animals, legends, made-up vocabulary and an old-fashioned adventure narrative. But it’s telling that this time around, what most amused me was Chapter 48, “Dea ex Machina,” in which a little girl rescues Hazel from her cat.

I recently finished a limping reread of Watership Down by Richard Adams. This was my favourite book as a child, but I couldn’t recapture the magic in my late thirties. The novelty this time around was in being able to recognize all the settings – the rabbits’ epic quest takes place on the outskirts of Newbury; we’ve walked through its countryside locations. (In fact, my husband, in his capacity as a town councillor, has testified at a hearing in objection to a plan to build 1000 houses at Sandleford, where the rabbits set out from.) I can see why I loved this at age nine: anthropomorphized animals, legends, made-up vocabulary and an old-fashioned adventure narrative. But it’s telling that this time around, what most amused me was Chapter 48, “Dea ex Machina,” in which a little girl rescues Hazel from her cat.

I’m 40 pages from the end of These Days by Lucy Caldwell, a beautiful novel set in Belfast in April 1941. A long central section is about “The Easter Raid.” I didn’t realize the devastation the city suffered during the Second World War. We see it mostly through the eyes of the Bell family – especially daughters Audrey, engaged to be married to a young doctor, and Emma, in love with a fellow female volunteer. I was wary of the characterization of the lower class, and the period slang can be a bit heavy-handed, but the evocation of a time of crisis is excellent, contrasting a departed normality with the new reality of bodies piled in the street and in makeshift morgues. It’s reminded me of The Night Watch by Sarah Waters.

I’m 40 pages from the end of These Days by Lucy Caldwell, a beautiful novel set in Belfast in April 1941. A long central section is about “The Easter Raid.” I didn’t realize the devastation the city suffered during the Second World War. We see it mostly through the eyes of the Bell family – especially daughters Audrey, engaged to be married to a young doctor, and Emma, in love with a fellow female volunteer. I was wary of the characterization of the lower class, and the period slang can be a bit heavy-handed, but the evocation of a time of crisis is excellent, contrasting a departed normality with the new reality of bodies piled in the street and in makeshift morgues. It’s reminded me of The Night Watch by Sarah Waters.

(I’ve also posted about my Easter reading, theological or not, in 2015, 2017, 2018 and 2021.)

20 Books of Summer, #6–8: Aristide, Hood, Lamott

This latest batch of colour-themed summer reads took me from a depleted post-pandemic landscape to the heart of dysfunctional families in Rhode Island and California.

Under the Blue by Oana Aristide (2021)

Fans of Station Eleven, this one’s for you: the best dystopian novel I’ve read since Mandel’s. Aristide started writing this in 2017, and unknowingly predicted a much worse pandemic than Covid-19. In July 2020, Harry, a middle-aged painter inhabiting his late nephew’s apartment in London, finally twigs that something major is going on. He packs his car and heads to his Devon cottage, leaving its address under the door of the cute neighbour he sometimes flirts with. Hot days stack up and his new habits of rationing food and soap are deeply ingrained by the time the gal from #22, Ash – along with her sister, Jessie, a doctor who stocked up on medicine before fleeing her hospital – turn up. They quickly sink into his routines but have a bigger game plan: getting to Uganda, where their mum once worked and where they know they will be out of range of Europe’s at-risk nuclear reactors. An epic road trip ensues.

It gradually becomes clear that Harry, Ash and Jessie are among mere thousands of survivors worldwide, somehow immune to a novel disease that spread like wildfire. There are echoes of Cormac McCarthy’s The Road in the way that they ransack the homes of the dead for supplies, and yet there’s lightness to their journey. Jessie has a sharp sense of humour, provoking much banter, and the places they pass through in France and Italy are gorgeous despite the circumstances. It would be a privilege to wander empty tourist destinations were it not for fear of nuclear winter and not finding sufficient food – and petrol to keep “the Lioness” (the replacement car they steal; it becomes their refuge) going. While the vague sexual tension between Harry and Ash persists, all three bonds are intriguing.

It gradually becomes clear that Harry, Ash and Jessie are among mere thousands of survivors worldwide, somehow immune to a novel disease that spread like wildfire. There are echoes of Cormac McCarthy’s The Road in the way that they ransack the homes of the dead for supplies, and yet there’s lightness to their journey. Jessie has a sharp sense of humour, provoking much banter, and the places they pass through in France and Italy are gorgeous despite the circumstances. It would be a privilege to wander empty tourist destinations were it not for fear of nuclear winter and not finding sufficient food – and petrol to keep “the Lioness” (the replacement car they steal; it becomes their refuge) going. While the vague sexual tension between Harry and Ash persists, all three bonds are intriguing.

In an alternating storyline starting in 2017, Lisa and Paul, two computer scientists based in a lab at the Arctic Circle, are programming an AI, Talos XI. Based on reams of data on history and human nature, Talos is asked to predict what will happen next. But when it comes to questions like the purpose of art and whether humans are worth saving, the conclusions he comes to aren’t the ones his creators were hoping for. These sections are set out as transcripts of dialogues, and provide a change of pace and perspective. Initially, I was less sure about this strand, worrying that it would resort to that well-worn trope of machines gone bad. Luckily, Aristide avoids sci-fi clichés, and presents a believable vision of life after the collapse of civilization.

The novel is full of memorable lines (“This absurd overkill, this baroque wedding cake of an apocalypse: plague and then nuclear meltdowns”) and scenes, from Harry burying a dead cow to the trio acting out a dinner party – just in case it’s their last. There’s an environmentalist message here, but it’s subtly conveyed via a propulsive cautionary tale that also reminded me of work by Louisa Hall and Maja Lunde. (Public library)

Ruby by Ann Hood (1998)

Olivia had the perfect life: fulfilling, creative work as a milliner; a place in New York City and a bolthole in Rhode Island; a new husband and plans to try for a baby right away. But then, in a fluke accident, David was hit by a car while jogging near their vacation home less than a year into their marriage. As the novel opens, 37-year-old Olivia is trying to formulate a letter to the college girl who struck and killed her husband. She has returned to Rhode Island to get the house ready to sell but changes her mind when a pregnant 15-year-old, Ruby, wanders in one day.

At first, I worried that the setup would be too neat: Olivia wants a baby but didn’t get a chance to have one with David before he died; Ruby didn’t intend to get pregnant and looks forward to getting back her figure and her life of soft drugs and petty crime. And indeed, Olivia suggests an adoption arrangement early on. But the outworkings of the plot are not straightforward, and the characters, both main and secondary (including Olivia’s magazine writer friend, Winnie; David’s friend, Rex; Olivia’s mother and sister; a local lawyer who becomes a love interest), are charming.

At first, I worried that the setup would be too neat: Olivia wants a baby but didn’t get a chance to have one with David before he died; Ruby didn’t intend to get pregnant and looks forward to getting back her figure and her life of soft drugs and petty crime. And indeed, Olivia suggests an adoption arrangement early on. But the outworkings of the plot are not straightforward, and the characters, both main and secondary (including Olivia’s magazine writer friend, Winnie; David’s friend, Rex; Olivia’s mother and sister; a local lawyer who becomes a love interest), are charming.

It’s a low-key, small-town affair reminiscent of the work of Anne Tyler, and I appreciated how it sensitively explores grief, its effects on the protagonist’s decision-making, and how daunting it is to start over (“The idea of that, of beginning again from nothing, made Olivia feel tired.”). It was also a neat touch that Olivia is the same age as me, so in some ways I could easily imagine myself into her position.

This was the ninth book I’ve read by Hood, an author little known outside of the USA – everything from grief memoirs to a novel about knitting. Ironically, its main themes of adoption and bereavement were to become hallmarks of her later work: she lost her daughter in 2002 and then adopted a little girl from China. (Secondhand purchase, June 2021)

[I’ve read another novel titled Ruby – Cynthia Bond’s from 2014.]

Blue Shoe by Anne Lamott (2002)

I’m a devoted reader of Lamott’s autobiographical essays about faith against the odds (see here), but have been wary of trying her fiction, suspecting I wouldn’t enjoy it as much. Well, it’s true that I prefer her nonfiction on the whole, but this was an enjoyably offbeat novel featuring the kind of frazzled antiheroine who wouldn’t be out of place in Anne Tyler’s work.

Mattie Ryder has left her husband and returned to her Bay Area family home with her young son and daughter. She promptly falls for Daniel, the handyman she hires to exterminate the rats, but he’s married, so she keeps falling into bed with her ex, Nicky, even after he acquires a new wife and baby. Her mother, Isa, is drifting ever further into dementia. A blue rubber shoe that Mattie finds serves as a totem of her late father – and his secret life. She takes a gamble that telling the truth, no matter what the circumstances, will see her right.

Mattie Ryder has left her husband and returned to her Bay Area family home with her young son and daughter. She promptly falls for Daniel, the handyman she hires to exterminate the rats, but he’s married, so she keeps falling into bed with her ex, Nicky, even after he acquires a new wife and baby. Her mother, Isa, is drifting ever further into dementia. A blue rubber shoe that Mattie finds serves as a totem of her late father – and his secret life. She takes a gamble that telling the truth, no matter what the circumstances, will see her right.

As in Ruby, I found the protagonist relatable and the ensemble cast of supporting characters amusing. Lamott crafts some memorable potted descriptions: “She was Jewish, expansive and yeasty and uncontained, as if she had a birthright for outrageousness” and “He seemed so constrained, so neatly trimmed, someone who’d been doing topiary with his soul all his life.” She turns a good phrase, and adopts the same self-deprecating attitude towards Mattie that she has towards herself in her memoirs: “She usually hoped to look more like Myrna Loy than an organ grinder’s monkey when a man finally proclaimed his adoration.”

At a certain point – maybe two-thirds of the way through – my inward reply to a lot of the novel’s threads was “okay, I get it; can we move on?” Yes, the situation with Isa is awful; yes, something’s gotta give with Daniel and his wife; yes, the revelations about her father seem unbearable. But with a four-year time span, it felt like Mattie was stuck in the middle for far too long. It’s also curious that she doesn’t apply her zany faith (a replica of Lamott’s) to questions of sexual morality – though that’s true of more liberal Christian approaches. All in all, I had some trouble valuing this as a novel because of how much I know about Lamott’s life and how closely I saw the storyline replicating her family dynamic. (Secondhand purchase, c. 2006 – I found a signed hardback in a library book sale back in my U.S. hometown for $1.)

Hmm, altogether too much blue in my selections thus far (4 out of 8!). I’ll have to try to come up with some more interesting colours for my upcoming choices.

Next books in progress: The Other’s Gold by Elizabeth Ames and God Is Not a White Man by Chine McDonald.

Read any of these? Interested?

Heartland by Sarah Smarsh

If you were a fan of Hillbilly Elegy by J.D. Vance, then debut author Sarah Smarsh’s memoir, Heartland, deserves to be on your radar too. Smarsh comes from five generations of Kansas wheat farmers and worked hard to step outside of the vicious cycle that held back the women on her mother’s side of the family: poverty, teen pregnancy, domestic violence, broken marriages, a lack of job security, and moving all the time. Like Mamaw in Vance’s book, Grandma Betty is the star of the show here: a source of pure love, she played a major role in raising Smarsh. The rundown of Betty’s life is sobering: her father was abusive and her mother had schizophrenia; she got pregnant at 16; and she racked up six divorces and countless addresses. This passage about her paycheck and diet jumped out at me:

Each month, after she paid the rent and utilities, and the landlady for watching Jeannie, Betty had $27 left. She budgeted some of it for cigarettes and gas. The rest went to groceries from the little store around the corner. The store sold frozen pot pies, five for a dollar. She’d buy twenty-five of them, beef and chicken flavor, and that would be her dinner all month. Every day, a candy bar for lunch at work and a frozen pot pie for dinner at home.

It’s a sad state of affairs when fatty processed foods are cheaper than healthy ones, and this is still the case today: the underprivileged are more likely to subsist on McDonald’s than on vegetables. Heartland is full of these kinds of contradictions. For instance, in the Reagan years the country shifted rightwards and working-class Catholics like Smarsh’s mother started voting Republican – in contravention of the traditional understanding that the Democrats were for the poor and the Republicans were for the rich. Smarsh followed her mother’s lead by casting her first-ever vote for George W. Bush in 2000, but her views changed in college when she learned how conservative fiscal policies keep people poor.

This isn’t a straightforward, chronological family story; it jumps through time and between characters. You might think of reading it as like joining Smarsh for an amble around the farm or a flip through a photograph album. Its vignettes are vivid, if sometimes hard to join into a cohesive story line in the mind. Some of the scenes that stood out to me were being pulled by truck through the snow on a canoe, helping Grandma Betty move into a house in Wichita but high-tailing it out of there when they realized it was infested by cockroaches, and the irony of winning a speech contest about drug addiction when her stepmother was hooked on opioids.

This isn’t a straightforward, chronological family story; it jumps through time and between characters. You might think of reading it as like joining Smarsh for an amble around the farm or a flip through a photograph album. Its vignettes are vivid, if sometimes hard to join into a cohesive story line in the mind. Some of the scenes that stood out to me were being pulled by truck through the snow on a canoe, helping Grandma Betty move into a house in Wichita but high-tailing it out of there when they realized it was infested by cockroaches, and the irony of winning a speech contest about drug addiction when her stepmother was hooked on opioids.

Heartland serves as a personal tour through some of the persistent trials of working-class life in the American Midwest: urbanization and the death of the family farm, an inability to afford health insurance and the threat of toxins encountered in the workplace, and the elusive dream of home ownership. Like Vance, Smarsh has escaped most of the worst possibilities through determination and education, so is able to bring an outsider’s clarity to the issues. At times she has a tendency to harp on the same points, though, adding in generalizations about the effects of poverty rather than just letting her family’s stories speak for themselves.

The oddest thing about Smarsh’s memoir – and I am certainly not the first reviewer to mention this since the book’s U.S. release in September – is who it’s directed to: her never-to-be-born daughter, “August”. Teen pregnancy was the family curse Smarsh was most desperate to avoid, and even now that she’s in her late thirties, a journalist and academic returned to Kansas after years on the East Coast, she remains childless. August is who Smarsh had in mind while working two or more jobs all through high school, earning higher degrees and buying her dream home. All along she was saving August from the hardships of a poor upbringing. While the unborn child is a potent symbol, it can be disorienting after pages of “I” to come across a “you” and have to readjust to who is being addressed.

Heartland is a striking book, not without its challenges to the reader, but one that I ultimately found rewarding to read in short bursts of 10 to 20 pages at a time. It’s worthwhile for anyone interested in what it’s really like to be poor in America.

My rating:

A favorite passage:

“My life has been a bridge between two places: the working poor and ‘higher’ economic classes. The city and the country. College-educated coworkers and disenfranchised loved ones. A somewhat conservative upbringing and a liberal adulthood. Home in the middle of the country and work on the East Coast. The physical world where I talk to people and the formless dimension where I talk to you.”

Heartland: A Memoir of Working Hard and Being Broke in the Richest Country on Earth was published by Scribe UK on November 8th. My thanks to the publisher for a free copy for review.