January 2022 Releases, Part I: Jami Attenberg and Roopa Farooki

It’s been a big month for new releases! I’m still working on a handful and will report back on two batches of three, tomorrow and Sunday; more will likely turn up in review roundups in future months. For today, I have a memoir in essays about a peripatetic writer’s life and an excerpt from my review of a junior doctor’s chronicle of the early days of the pandemic.

I Came All This Way to Meet You: Writing Myself Home by Jami Attenberg

I’ve enjoyed Attenberg’s four most recent novels (reviewed here: The Middlesteins and All This Could Be Yours) so was intrigued to hear that she was trying out nonfiction. She self-describes as a “moderately successful author,” now in her early fifties – a single, independent feminist based in New Orleans after years in Manhattan and then Brooklyn. (Name-dropping of author friends: “Lauren” (Groff), “Kristen” (Arnett) and “Viola” (di Grado), with whom she stays in Italy.) Leaving places abruptly had become a habit; travelling from literary festival to holiday to writing residency was her way of counterbalancing a safe, quiet writing life at home. She tells of visiting a friend in Hong Kong and teaching fiction for two weeks in Vilnius – where she learned that, despite her Jewish heritage, Holocaust tourism is not her thing. Anxiety starts to interfere with travel, though, and she takes six months off flying. Owning a New Orleans home where she can host guests is the most rooted she’s ever been.

I’ve enjoyed Attenberg’s four most recent novels (reviewed here: The Middlesteins and All This Could Be Yours) so was intrigued to hear that she was trying out nonfiction. She self-describes as a “moderately successful author,” now in her early fifties – a single, independent feminist based in New Orleans after years in Manhattan and then Brooklyn. (Name-dropping of author friends: “Lauren” (Groff), “Kristen” (Arnett) and “Viola” (di Grado), with whom she stays in Italy.) Leaving places abruptly had become a habit; travelling from literary festival to holiday to writing residency was her way of counterbalancing a safe, quiet writing life at home. She tells of visiting a friend in Hong Kong and teaching fiction for two weeks in Vilnius – where she learned that, despite her Jewish heritage, Holocaust tourism is not her thing. Anxiety starts to interfere with travel, though, and she takes six months off flying. Owning a New Orleans home where she can host guests is the most rooted she’s ever been.

Along with nomadism, creativity and being a woman are key themes. Attenberg notices how she’s treated differently from male writers at literary events, and sometimes has to counter antifeminist perspectives even from women – as in a bizarre debate she ended up taking part in at a festival in Portugal. She takes risks and gets hurt, physically and emotionally. Break-ups sting, but she moves on and tries to be a better person. There are a lot of hard-hitting one-liners about the writing life and learning to be comfortable in one’s (middle-aged) body:

I believe that one must arrive at an intersection of hunger and fear to make great art.

Who was I hiding from? I was only ever going to be me. I was only ever going to have this body forever. Life was too short not to have radical acceptance of my body.

Whenever my life turns into any kind of cliché, I am furious. Not me, I want to scream. Not me, I am special and unusual. But none of us are special and unusual. Our stories are all the same. It is just how you tell them that makes them worth hearing again.

I did not know yet how books would save me over and over again. I did not know that a book was a reason to live. I did not know that being alive was a reason to live.

Late on comes her #MeToo story, which in some ways feels like the core of the book. When she was in college, a creative writing classmate assaulted her on campus while drunk. She reported it but nothing was ever done; it only led to rumours and meanness towards her, and a year later she attempted suicide. You know how people will walk into a doctor’s appointment and discuss three random things, then casually drop in a fourth that is actually their overriding concern? I felt that way about this episode: that really the assault was what Attenberg wanted to talk about, and could have devoted much more of the book to.

The chapters are more like mini essays, flitting between locations and experiences in the same way she has done, and sometimes repeating incidents. I think the intent was to mimic, and embrace, the random shape that a life takes. Each vignette is like a competently crafted magazine piece, but the whole is no more than the sum of the parts.

With thanks to Serpent’s Tail for the proof copy for review.

Everything Is True: A Junior Doctor’s Story of Life, Death and Grief in a Time of Pandemic by Roopa Farooki

Farooki is a novelist, lecturer, mum of four, and junior doctor. Her storytelling choices owe more to literary fiction than to impassive reportage. The second-person, present-tense narration drops readers right into her position. Frequent line breaks and repetition almost give the prose the rhythm of performance poetry. There is also wry humour, wordplay, slang and cursing. In February 2020, her sister Kiron had died of breast cancer. During the first 40 days of the initial UK lockdown – the book’s limited timeframe – she continues to talk to Kiron, and imagines she can hear her sister’s chiding replies. Grief opens the door for magic realism, despite the title – which comes from a Balzac quote. A hybrid work that reads as fluidly as a novel while dramatizing real events, this is sure to appeal to people who wouldn’t normally pick up a bereavement or medical memoir. (Full review coming soon at Shiny New Books.)

Farooki is a novelist, lecturer, mum of four, and junior doctor. Her storytelling choices owe more to literary fiction than to impassive reportage. The second-person, present-tense narration drops readers right into her position. Frequent line breaks and repetition almost give the prose the rhythm of performance poetry. There is also wry humour, wordplay, slang and cursing. In February 2020, her sister Kiron had died of breast cancer. During the first 40 days of the initial UK lockdown – the book’s limited timeframe – she continues to talk to Kiron, and imagines she can hear her sister’s chiding replies. Grief opens the door for magic realism, despite the title – which comes from a Balzac quote. A hybrid work that reads as fluidly as a novel while dramatizing real events, this is sure to appeal to people who wouldn’t normally pick up a bereavement or medical memoir. (Full review coming soon at Shiny New Books.)

A great addition to my Covid chronicles repertoire!

With thanks to Bloomsbury for the proof copy for review.

Would one of these books interest you?

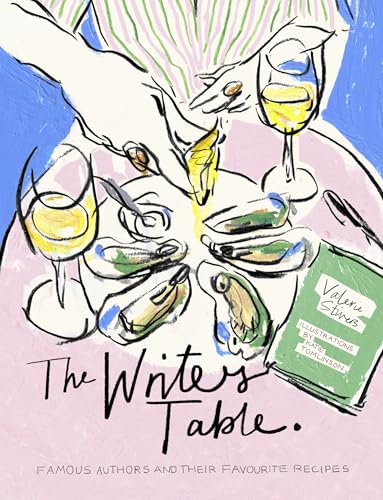

Though I’ve read a lot by and about D.H. Lawrence, I didn’t realise he did all the cooking in his household with Frieda, and was renowned for his bread. And who knew that Emily Dickinson was better known in her lifetime as a baker? Her coconut cake is beautifully simple, containing just six ingredients. Flannery O’Connor’s peppermint chiffon pie also sounds delicious. Some essays do not feature a recipe but a discussion of food in an author’s work, such as the unusual combinations of mostly tinned foods that Iris Murdoch’s characters eat. It turns out that that’s how she and her husband John Bayley ate, so she saw nothing odd about it. And Murakami’s 2005 New Yorker story “The Year of Spaghetti” is about a character whose fixation on one foodstuff reflects, Stivers notes, his “emotional … turmoil.”

Though I’ve read a lot by and about D.H. Lawrence, I didn’t realise he did all the cooking in his household with Frieda, and was renowned for his bread. And who knew that Emily Dickinson was better known in her lifetime as a baker? Her coconut cake is beautifully simple, containing just six ingredients. Flannery O’Connor’s peppermint chiffon pie also sounds delicious. Some essays do not feature a recipe but a discussion of food in an author’s work, such as the unusual combinations of mostly tinned foods that Iris Murdoch’s characters eat. It turns out that that’s how she and her husband John Bayley ate, so she saw nothing odd about it. And Murakami’s 2005 New Yorker story “The Year of Spaghetti” is about a character whose fixation on one foodstuff reflects, Stivers notes, his “emotional … turmoil.”

Baumgartner’s past is similar to Auster’s (and Adam Walker’s from Invisible – the two characters have a mutual friend in writer James Freeman), but not identical. His childhood memories and the passion and companionship he found with Anna are quite sweet. But I was somewhat thrown by the tone in sections that have this grumpy older man experiencing pseudo-comic incidents such as tumbling down the stairs while showing the meter reader the way. To my relief, the book doesn’t take the tragic turn the last pages seem to augur, instead leaving readers with a nicely open ending.

Baumgartner’s past is similar to Auster’s (and Adam Walker’s from Invisible – the two characters have a mutual friend in writer James Freeman), but not identical. His childhood memories and the passion and companionship he found with Anna are quite sweet. But I was somewhat thrown by the tone in sections that have this grumpy older man experiencing pseudo-comic incidents such as tumbling down the stairs while showing the meter reader the way. To my relief, the book doesn’t take the tragic turn the last pages seem to augur, instead leaving readers with a nicely open ending. This is very much in the vein of

This is very much in the vein of

A debut trio of raw stories set in the Yorkshire countryside. In “Offcomers,” the 2001 foot and mouth disease outbreak threatens the happiness of a sheep-farming couple. The effects of rural isolation on a relationship resurface in “Outside Are the Dogs.” In “Cull Yaw,” a vegetarian gets involved with a butcher who’s keen on marketing mutton and ends up helping him with a grisly project. This was the stand-out for me. I appreciated the clear-eyed look at where food comes from. At the same time, narrator Star’s mother is ailing: a reminder that decay is inevitable and we are all naught but flesh and blood. I liked the prose well enough, but found the characterization a bit thin. One for readers of Andrew Michael Hurley and Cynan Jones. (See also

A debut trio of raw stories set in the Yorkshire countryside. In “Offcomers,” the 2001 foot and mouth disease outbreak threatens the happiness of a sheep-farming couple. The effects of rural isolation on a relationship resurface in “Outside Are the Dogs.” In “Cull Yaw,” a vegetarian gets involved with a butcher who’s keen on marketing mutton and ends up helping him with a grisly project. This was the stand-out for me. I appreciated the clear-eyed look at where food comes from. At the same time, narrator Star’s mother is ailing: a reminder that decay is inevitable and we are all naught but flesh and blood. I liked the prose well enough, but found the characterization a bit thin. One for readers of Andrew Michael Hurley and Cynan Jones. (See also

Okorie emigrated from Nigeria to Ireland in 2005. Her time living in a direct provision hostel for asylum seekers informed the title story about women queuing for and squabbling over food rations, written in an African pidgin. In “Under the Awning,” a Black woman fictionalizes her experiences of racism into a second-person short story her classmates deem too bleak. The Author’s Note reveals that Okorie based this one on comments she herself got in a writers’ group. “The Egg Broke” returns to Nigeria and its old superstition about twins.

Okorie emigrated from Nigeria to Ireland in 2005. Her time living in a direct provision hostel for asylum seekers informed the title story about women queuing for and squabbling over food rations, written in an African pidgin. In “Under the Awning,” a Black woman fictionalizes her experiences of racism into a second-person short story her classmates deem too bleak. The Author’s Note reveals that Okorie based this one on comments she herself got in a writers’ group. “The Egg Broke” returns to Nigeria and its old superstition about twins. This is the third time Simpson has made it into one of my September features (after

This is the third time Simpson has made it into one of my September features (after  The subtitle – “Great Writers at the End” – gives you a hint of what to expect from this erudite, elegiac work of literary biography. In a larger sense, it is about coming to terms with the fear of death, one of the last enduring Western phobias.

The subtitle – “Great Writers at the End” – gives you a hint of what to expect from this erudite, elegiac work of literary biography. In a larger sense, it is about coming to terms with the fear of death, one of the last enduring Western phobias.

![Freud with one of his beloved cigars, 1922. Max Halberstadt [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.](https://bookishbeck.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/freud-and-cigar.jpg?w=213&h=300)