Literary Wives Club: The Harpy by Megan Hunter

(My fifth read with the Literary Wives online book club; see also Kay’s and Naomi’s reviews.)

Megan Hunter’s second novella, The Harpy (2020), treads familiar ground – a wife discovers evidence of her husband’s affair and questions everything about their life together – but somehow manages to feel fresh because of the mythological allusions and the hint of how female rage might reverse familial patterns of abuse.

Lucy Stevenson is a mother of two whose husband Jake works at a university. One day she opens a voicemail message on her phone from a David Holmes, saying that he thinks Jake is having an affair with his wife, Vanessa. Lucy vaguely remembers meeting the fiftysomething couple, colleagues of Jake’s, at the Christmas party she hosted the year before.

As further confirmation arrives and Lucy tries to carry on with everyday life (another Christmas party, a pirate-themed birthday party for their younger son), she feels herself transforming into a wrathful, ravenous creature – much like the harpies she was obsessed with as a child and as a Classics student before she gave up on her PhD.

Like the mythical harpy, Lucy administers punishment. At first, it’s something of a joke between her and Jake: he offers that she can ritually harm him three times. Twice it takes physical form; once it’s more about reputational damage. The third time, it goes farther than either of them expected. It’s clever how Hunter presents this formalized violence as an inversion of the domestic abuse of which Lucy’s mother was a victim.

Lucy also expresses anger at how women are objectified, and compares three female generations of her family in terms of how housewifely duties were embraced or rejected. She likens the grief she feels over her crumbling marriage to contractions or menstrual cramps. It’s overall a very female text, in the vein of A Ghost in the Throat. You feel that there’s a solidarity across time and space of wronged women getting their own back. I enjoyed this so much more than Hunter’s debut, The End We Start From. (Birthday gift from my wish list)

The main question we ask about the books we read for Literary Wives is:

What does this book say about wives or about the experience of being a wife?

“Marriage and motherhood are like death … no one comes back unchanged.”

So much in life can remain unspoken, even in a relationship as intimate as a marriage. What becomes routine can cover over any number of secrets; hurts can be harboured until they fuel revenge. Lucy has lost her separate identity outside of her family relationships and needs to claw back a sense of self.

I don’t know that this book said much that is original about infidelity, but I sympathized with Lucy’s predicament. The literary and magical touches obscure the facts of the ending, so it’s unclear whether she’ll stay with Jake or not. Because we’re mired in her perspective, it’s hard to see Jake or Vanessa clearly. Our only choice is to side with Lucy.

Next book: Sea Wife by Amity Gaige in September

10 Days in the USA and What I Read (Plus a Book Haul)

On October 29th, I went to an evening drinks party at a neighbour’s house around the corner. A friend asked me about whether the UK or the USA is “home” and I replied that the States feels less and less like home every time I go, that the culture and politics are ever more foreign to me and the UK’s more progressive society is where I belong. I even made an offhand comment to the effect of: once my mother passed, I didn’t think I’d fly back there often, if at all. I was thinking about 5–10 years into the future; instead, a few hours after I got home from the party, we were awoken by the middle-of-the-night phone call saying my mother had suffered a nonrecoverable brain bleed. The next day she was gone.

I haven’t reflected a lot on the irony of that timing, probably because it feels like too much, but it turns out I was completely wrong: in fact, I’m now returning to the States more often. With our mom gone and our dad not really in our lives, my sister and I have gotten closer. Since October I’ve flown back twice and she’s visited here once. There are 7.5 years between us and we’ve always been at different stages of life, with separate preoccupations and priorities; I was also lazy and let my mom be the go-between, passing family news back and forth. Now there’s a sense that we are all we have, and we have to stick together.

So it was doubly important for me to be there for my sister’s graduation from nursing school last week. If we follow each other on Facebook or Instagram, you will have already seen that she finished at the top of her cohort and was one of just two students recognized for academic excellence out of the college’s over 200 graduates – and all of this while raising four children and coping with the disruption of Mom’s death seven months ago. There were many times when she thought she would have to pause or give up her studies, but she persisted and will start work as a hospice nurse soon. We’re all as proud as could be, on our mom’s behalf, too.

The trip was a mixture of celebratory moments and sad duties. We started the process of going through our mom’s belongings and culling what we can, but the files, photos and mementoes are the real challenge and had to wait for another time. There were dozens of books I’d given her for birthdays and holidays, mostly by her favourite gentle writers – Gerald Durrell, Jan Karon, Gervase Phinn – invariably annotated with her name, the date and occasion. I looked back through them and then let them go.

Between my two suitcases I managed to bring back the rest of her first box of journals (there are 150 of them in total, spanning 1989 to 2022), and I’m halfway through #4 at the moment. We moved out of my first home when I was nine, and I don’t have a lot of vivid memories of those early years. But as I read her record of everyday life it’s like I’m right back in those rooms. I get new glimpses of myself, my dad, my sister, but especially of her – not as my mother, but as a whole person. As a child I never realized she was depressed: distressed about her job situation, worried over conflicts with her siblings and my sister, coping with ill health (she was later diagnosed with fibromyalgia) and resisting ageing. For as strong as her Christian faith was, she was really struggling in ways I couldn’t appreciate then.

I hope that later journals will introduce hindsight, now that she’s not around to give a more circumspect view. In any case, they’re an incredible legacy, a chance for me to relive much of my life that I otherwise would only remember in fragments through photographs, and perhaps have a preview of what I can expect from the course of our shared kidney disease.

What I Read

The Housekeepers by Alex Hay – A historical heist novel with shades of Downton Abbey, this comes out in July. Reviewed for Shelf Awareness.

The Housekeepers by Alex Hay – A historical heist novel with shades of Downton Abbey, this comes out in July. Reviewed for Shelf Awareness.

Cowboys Are My Weakness by Pam Houston – Terrific: stark, sexy stories about women who live out West and love cowboys and hunters (as well as dogs and horses). Ten of the stories are in the first person, voiced by women in their twenties and thirties who are looking for romance and adventure and anxiously pondering motherhood (“by the time you get to be thirty, freedom has circled back on itself to mean something totally different from what it did at twenty-one”). The remaining two are in the second person, which I always enjoy. The occasional Montana setting reminded me of stories I’ve read by Maile Meloy and Maggie Shipstead, while the relationship studies made me think of Amy Bloom’s work.

The Harpy by Megan Hunter – Read for Literary Wives club. Review coming up on Monday.

The Lake Shore Limited by Sue Miller – A solid set of narratives alternating between the POVs of four characters whose lives converge around a play inspired by the playwright’s loss of her boyfriend on one of the hijacked planes on 9/11. Her mixed feelings about him towards the end of his life and about being shackled to his legacy as his ‘widow’ reverberate in other sections: one about the lead actor, whose wife has ALS; and one about a widower the playwright is being set up with on a date. Fitting for a book about a play, the scenes feel very visual. A little underpowered, but subtlety is to be expected from a Miller novel. She, Anne Tyler and Elizabeth Berg write easy reads with substance, just the kind of book I want to take on an airplane, as indeed I did with this one. I read the first 2/3 on my travel day (although with the 9/11 theme this maybe wasn’t the best choice!).

For apposite plane reading, I also started Fly Girl by Ann Hood, her memoir of being a TWA flight attendant in the 1970s, the waning glory days of air travel. I’ve read 10 or so of Hood’s books before from various genres, but lost interest in the minutiae of her job applications and interviews. Another writer would probably have made a bigger deal of the inherent sexism of the profession, too. I read 30%.

For apposite plane reading, I also started Fly Girl by Ann Hood, her memoir of being a TWA flight attendant in the 1970s, the waning glory days of air travel. I’ve read 10 or so of Hood’s books before from various genres, but lost interest in the minutiae of her job applications and interviews. Another writer would probably have made a bigger deal of the inherent sexism of the profession, too. I read 30%.

Hello Beautiful by Ann Napolitano – I knew I wanted to read this even before it was Oprah’s 100th book club pick. It’s a family story spanning three decades and focusing on the Padavanos, a working-class Italian American Chicago clan with four daughters: Julia, Sylvie, and twins Cecilia and Emeline. Julia meets melancholy basketball player William Waters while at Northwestern in the late 1970s and they marry and have a daughter; Sylvie, a budding librarian, makes out with boys in the stacks until her great romance comes along; Cecilia is an artist and Emeline loves babies and manages a nursery. More than once a character think of their collective story as a “soap opera,” and there’s plenty of melodrama here – an out-of-wedlock pregnancy, estrangements, a suicide attempt, a coming out, stealing another’s man – as well as far-fetched coincidences, including the two major deaths falling on the same day as a birth and a reconciliation.

Hello Beautiful by Ann Napolitano – I knew I wanted to read this even before it was Oprah’s 100th book club pick. It’s a family story spanning three decades and focusing on the Padavanos, a working-class Italian American Chicago clan with four daughters: Julia, Sylvie, and twins Cecilia and Emeline. Julia meets melancholy basketball player William Waters while at Northwestern in the late 1970s and they marry and have a daughter; Sylvie, a budding librarian, makes out with boys in the stacks until her great romance comes along; Cecilia is an artist and Emeline loves babies and manages a nursery. More than once a character think of their collective story as a “soap opera,” and there’s plenty of melodrama here – an out-of-wedlock pregnancy, estrangements, a suicide attempt, a coming out, stealing another’s man – as well as far-fetched coincidences, including the two major deaths falling on the same day as a birth and a reconciliation.

There is such warmth and intensity to the telling, and brave reckoning with mental illness, prejudice and trauma, that I excused flaws such as dwelling overly much in characters’ heads through close third person narration, to the detriment of scenes and dialogue. I love sister stories in general, and the subtle echoes of Leaves of Grass and Little Women (the connections aren’t one to one and you’re kept guessing for most of the book who will be the Beth) add heft. I especially appreciated how a late parent is still remembered in daily life after 30 years have passed. This is, believe it or not, the second basketball novel I’ve loved this year, after Tell the Rest by Lucy Jane Bledsoe.

I always try to choose thematically appropriate reads, so I also started:

Circling My Mother by Mary Gordon – A memoir she began after her nonagenarian mother’s death with dementia. Intriguingly, the structure is not chronological but topic by topic, built around key relationships: so far I’ve read “My Mother and Her Bosses” and “My Mother: Words and Music.”

Circling My Mother by Mary Gordon – A memoir she began after her nonagenarian mother’s death with dementia. Intriguingly, the structure is not chronological but topic by topic, built around key relationships: so far I’ve read “My Mother and Her Bosses” and “My Mother: Words and Music.”

Grave by Allison C. Meier – My sister and I made a day trip up to my mother’s grave for the first time since her burial. She has a beautiful spot in a rural cemetery dating back to the 1780s, but it’s in full sun and very dry, so we tried to cheer up the dusty plot with some extra topsoil and grass seed, marigolds, and a butterfly flag.

Meier is a cemetery tour guide in Brooklyn, where she lives. In the third of the e-book I’ve read so far, she looks at American burial customs, the lack of respect for Black and Native American burial sites, and the rise of garden cemeteries such as Mount Auburn in Cambridge, Massachusetts. I’ve been reading death-themed books for over a decade and have delighted in exploring cemeteries (including Mount Auburn, as part of my New England honeymoon) for even longer, so this is right up my street and one of the better Object Lessons monographs.

Meier is a cemetery tour guide in Brooklyn, where she lives. In the third of the e-book I’ve read so far, she looks at American burial customs, the lack of respect for Black and Native American burial sites, and the rise of garden cemeteries such as Mount Auburn in Cambridge, Massachusetts. I’ve been reading death-themed books for over a decade and have delighted in exploring cemeteries (including Mount Auburn, as part of my New England honeymoon) for even longer, so this is right up my street and one of the better Object Lessons monographs.

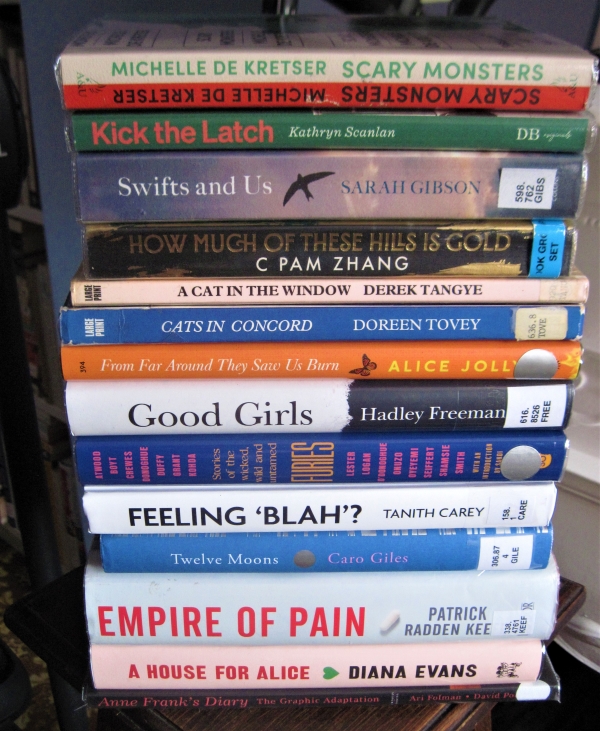

What I Bought

I traded in most of my mother’s books at 2nd & Charles and Wonder Book and Video but, no surprise, promptly spent the store credit on more secondhand books. Thanks to clearance shelves at both stores, I only had to chip in another $12.25 for the below haul, which also covered two Dollar Tree purchases (I felt bad for Susan Minot having signed editions end up remaindered!). Some tried and true authors here, as well as novelties to test out, with a bunch of short stories and novellas to read later in the year.

20 Books of Summer 2023 Plan

It’s my sixth year participating in Cathy’s 20 Books of Summer challenge, which starts today and runs through the 1st of September. In previous years I’ve chosen a theme.

2018: Books by women

2019: Fauna

2020: Food

2021: Colours

2022: Flora

Only in 2018, I think, was I strict enough with myself to only read books that I own, but every year that’s been my main goal: to clear things from the print TBR.

So, that means: no library books, no review copies bar the long-neglected backlog or the set-aside ones, and Kindle books only if I purchased them. Though I won’t be prescriptive about it, I’d like to prioritize hardbacks, recent acquisitions or longtime shelf-sitters, and books by women.

I thought about having no theme, or multiple mini ones, this year. However, I’ve amassed so many foodie reads that I could easily fill my 20 just with that topic (fiction and nonfiction pictured below, with some supplementary summery reads at left), so I’ll see how I go.

Below is my set-aside and review backlog area, which takes up much of the top two shelves. The bottom shelf is books I’m keen to reread. I could easily select some of my 20 from here.

I hoped to get ahead by reading one or two relevant books on the plane back from America, where I’ve been for the last 10 days for my sister’s nursing school graduation and some sadmin for my mom. Did I manage it? After I get over the jet lag, I’ll report back with my first read or two.

Are you joining in the summer reading challenge? What’s the first book on the docket?

Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma by Claire Dederer

The question posed by Claire Dederer’s third hybrid work of memoir and cultural criticism might be stated thus: “Are we still allowed to enjoy the art made by horrible people?” You might be expecting a hard-line response – prescriptive rules for cancelling the array of sexual predators, drunks, abusers and abandoners (as well as lesser offenders) she profiles. Maybe you’ve avoided Monsters for fear of being chastened about your continuing love of Michael Jackson’s music or the Harry Potter series. I have good news: This book is as compassionate as it is incisive, and while there is plenty of outrage, there is also much nuance.

Dederer begins, in the wake of #MeToo, with film directors Roman Polanski and Woody Allen, setting herself the assignment of re-watching their masterpieces while bearing in mind their sexual crimes against underage women. In a later chapter she starts referring to this as “the stain,” a blemish we can’t ignore when we consider these artists’ work. Try as we might to recover prelapsarian innocence, it’s impossible to forget allegations of misconduct when watching The Cosby Show or listening to Miles Davis’s Kind of Blue. Nor is it hard to find racism and anti-Semitism in the attitude of many a mid-20th-century auteur.

Does “genius” excuse all? Dederer asks this in relation to Picasso and Hemingway, then counteracts that with a fascinating chapter about Lolita – as far as we know, Nabokov never engaged in, or even contemplated, sex with minors, but he was able to imagine himself into the mind of Humbert Humbert, an unforgettable antihero who did. “The great writer knows that even the blackest thoughts are ordinary,” she writes. Although she doesn’t think Lolita could get published today, she affirms it as a devastating picture of stolen childhood.

“The death of the author” was a popular literary theory in the 1960s that now feels passé. As Dederer notes, in the Internet age we are bombarded with biographical information about favourite writers and musicians. “The knowledge we have about celebrities makes us feel we know them,” and their bad “behavior disrupts our ability to apprehend the work on its own terms.” This is not logical, she emphasizes, but instinctive and personal. Some critics (i.e., white men) might be wont to dismiss such emotional responses as feminine. Super-fans are indeed more likely to be women or teenagers, and heartbreak over an idol’s misdoings is bound up with the adoration, and sense of ownership, of the work. She talks with many people who express loyalty “even after everything” – love persists despite it all.

U.S. cover

In a book largely built around biographical snapshots and philosophical questions, Dederer’s struggle to make space for herself as a female intellectual, and write a great book, is a valuable seam. I particularly appreciated her deliberations on the critic’s task. She insists that, much as we might claim authority for our views, subjectivity is unavoidable. “We are all bound by our perspectives,” she asserts; “consuming a piece of art is two biographies meeting: the biography of the artist, which might disrupt the consuming of the art, and the biography of the audience member, which might shape the viewing of the art.”

While men’s sexual predation is a major focus, the book also weighs other sorts of failings: abandonment of children and alcoholism. The “Abandoning Mothers” chapter posits that in the public eye this is the worst sin that a woman can commit. Her two main examples are Doris Lessing and Joni Mitchell, but there are many others she could have mentioned. Even giving more mental energy to work than to childrearing is frowned upon. Dederer wonders if she has been a monster in some ways, and confronts her own drinking problem.

A painting by Cathy Lomax of girls at a Bay City Rollers concert.

Here especially, the project reminded me most of books by Olivia Laing: the same mixture of biographical interrogation, feminist cultural criticism, and memoir as in The Trip to Echo Spring and Everybody; some subjects even overlap (Raymond Carver in the former; Ana Mendieta and Valerie Solanas in the latter – though, unfortunately, these two chapters by Dederer were the ones I thought least necessary; they could easily have been omitted without weakening the argument in any way). I also thought of how Lara Feigel’s Free Woman examines her own life through the prism of Lessing’s.

The danger of being quick to censure any misbehaving artist, Dederer suggests, is a corresponding self-righteousness that deflects from our own faults and hypocrisy. If we are the enlightened ones, we can look back at the casual racism and daily acts of violence of other centuries and say: “1. These people were simply products of their time. 2. We’re better now.” But are we? Dederer redirects all the book’s probing back at us, the audience. If we’re honest about ourselves, and the people we love, we will admit that we are all human and so capable of monstrous acts.

Dederer’s prose is forthright and droll; lucid even when tackling thorny issues. She has succeeded in writing the important book she intended to. Erudite, empathetic and engaging from start to finish, this is one of the essential reads of 2023.

With thanks to Sceptre for the free copy for review.

Buy Monsters from Bookshop.org [affiliate link]

Love Your Library, May 2023

Thanks to Elle for her monthly contribution, Laura for her great reviews of two high-profile novels, Birnam Wood and Pod, borrowed from her local library, and Naomi for the write-up of her recent audiobook loans, a fascinating selection of nonfiction and middle grade fiction. I forgot to link to Jana’s post last month, so here’s her April reading, another very interesting set.

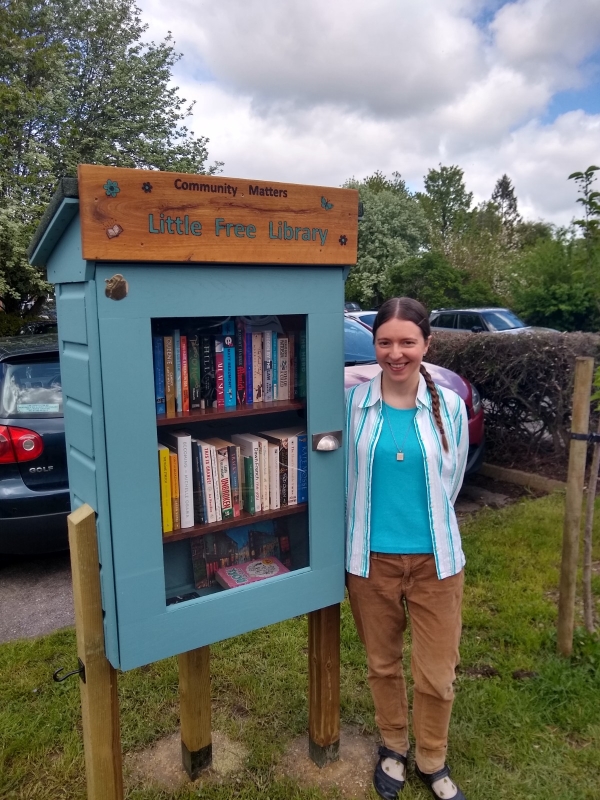

My biggest news this month is that we now have a Little Free Library in my neighbourhood. This project was several years in the making as we waited for permissions and funding. The box (and a wooden bench next to it) were hand-crafted by my very talented neighbours, and the mayor of Newbury came to officially open it on the 7th. There are also a few planters of perennials and a small cherry tree. It really cheers up what used to be a patch of bare grass next to a parking area.

I’m the volunteer curator/librarian/steward so will ensure that the shelves are tidy and the stock keeps turning over. I try to stop by daily since it’s only around the corner from my house. We’ve ordered a charter sign to link us up with the organization and put us on the official map. Anyone visiting Newbury might decide to come find it. (I, for one, look out for LFLs wherever I go, from Pennsylvania to North Uist!)

My library reading and borrowing since last month. I’m back in the States for a visit just now, so don’t currently have any library books on the go. It felt prudent to clear the decks, but I’ll have a big stack waiting for me when I come back!

READ

- I Can’t Date Jesus: Love, Sex, Family, Race, and Other Reasons I’ve Put My Faith in Beyoncé by Michael Arceneaux

- Shadow Girls by Carol Birch

- The Cats We Meet Along the Way by Nadia Mikail

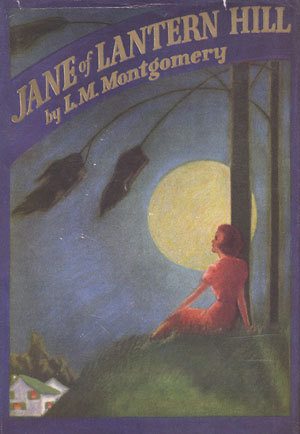

- Jane of Lantern Hill by L.M. Montgomery

- My Father’s House by Joseph O’Connor

- The Boy Who Lost His Spark by Maggie O’Farrell

- Mrs. Palfrey at the Claremont by Elizabeth Taylor

- Glowing Still: A Woman’s Life on the Road by Sara Wheeler

- In Memoriam by Alice Winn

SKIMMED

- Fire Rush by Jacqueline Crooks

- You Are Not Alone by Cariad Lloyd

CHECKED OUT, TO BE READ

RETURNED UNFINISHED

- All the Men I Never Married by Kim Moore – I hadn’t heard of the poet and had never read anything from the publisher, but took a chance. I got to page 16. It’s fine: poems about former love interests, whether they be boyfriends or aggressors. There looks to be good variety of structure. I just didn’t sense adequate weight.

- The Furrows by Namwali Serpell – My apologies to Laura! (This started off as a buddy read.) I pushed myself through the first 78 pages, but once it didn’t advance in the Carol Shields Prize race there was no impetus to continue and it just wasn’t compelling enough to finish.

What have you been reading or reviewing from the library recently?

Share a link to your own post in the comments. Feel free to use the above image. The hashtag is #LoveYourLibrary.

Jane of Lantern Hill by L.M. Montgomery (1937) #ReadingLanternHill

I’m grateful to Canadian bloggers Naomi (Consumed by Ink) and Sarah for hosting the readalong: It’s been a pure pleasure to discover this lesser-known work by Lucy Maud Montgomery.

{SOME SPOILERS IN THE FOLLOWING}

Like Anne of Green Gables, this is a cosy novel about finding a home and a family. Fairytale-like in its ultimate optimism, it nevertheless does not avoid negative feelings. It also seemed to me ahead of its time in how it depicts parental separation.

Jane Victoria Stuart lives with her beautiful, flibbertigibbet mother and strict grandmother in a “shabby genteel” mansion on the ironically named Gay Street in Toronto. Grandmother calls her Victoria and makes her read the Bible to the family every night, a ritual Jane hates. Jane is an indifferent student, though she loves writing, and her best friend is Jody, an orphan who is in service next door. Her mother is a socialite breezing out each evening, but she doesn’t seem jolly despite all the parties. Jane has always assumed her father is dead, so it is a shock when a girl at school shares the rumour that her father is alive and living on Prince Edward Island. Apparently, divorce was difficult in Canada at that time and would have required a trip to the USA, so for nearly a decade the couple have been estranged.

It’s not just Jane who feels imprisoned on Gay Street: her mother and Jody are both suffering in their own ways, and long to live unencumbered by others’ strictures. For Jane, freedom comes when her father requests custody of her for the summer. Grandmother is of a mind to ignore the summons, but the wider family advise her to heed it. Initially apprehensive, Jane falls in love with PEI and feels like she’s known her father, a jocular writer, all the time. They’re both romantics and go hunting for a house that will feel like theirs right away. Lantern Hill fits the bill, and Jane delights in playing the housekeeper and teaching herself to cook and garden. Returning to Toronto in the autumn is a wrench, but she knows she’ll be back every summer. It’s an idyll precisely because it’s only part time; it’s a retreat.

Jane is an appealing heroine with her can-do attitude. Her everyday adventures are sweet – sheltering in a barn when the car breaks down, getting a reward and her photo in the paper for containing an escaped circus lion – but I was less enamoured with the depiction of the quirky locals. The names alone point to country bumpkin stereotypes: Shingle Snowbeam, Ding-dong, the Jimmy Johns. I did love Little Aunt Em, however, with her “I smack my lips over life” outlook. Meddlesome Aunt Irene could have been less one-dimensional; Jody’s adoption by the Titus sisters is contrived (and closest in plot to Anne); and Jane’s late illness felt unnecessary. While frequent ellipses threatened to drive me mad, Montgomery has sprightly turns of phrase: “A dog of her acquaintance stopped to speak to her, but Jane ignored him.”

Could this have been one of the earliest stories of a child who shuttles back and forth between separated or divorced parents? I wondered if it was considered edgy subject matter for Montgomery. There is, however, an indulging of the stereotypical broken-home-child fantasy of the parents still being in love and reuniting. If this is a fairytale setup, Grandmother is the evil ogre who keeps the princess(es) locked up in a gloomy castle until the noble prince’s rescue. I’m sure both Toronto and PEI are lovely in their own way – alas, I’ve never been to Canada – and by the end Montgomery offers Jane a bright future in both.

Small qualms aside, I loved reading Jane of Lantern Hill and would recommend it to anyone who enjoyed the Anne books. It’s full of the magic of childhood. What struck me most, and will stick with me, is the exploration of how the feeling of being at home (not just having a house to live in) is essential to happiness. (University library)

#ReadingLanternHill

Buy Jane of Lantern Hill from Bookshop.org [affiliate link]

In Memoriam by Alice Winn: Review & Author Event

I read In Memoriam by Alice Winn last month, then had the chance to see the author in conversation at Hungerford Town Hall, an event hosted by Hungerford Bookshop, on Friday evening. Here’s what I thought of the novel, which is on my Best of 2023 list.

Review

Heartstopper on the Western Front; swoon! It’s literary fiction set in the trenches of WWI, yes, but also a will-they-won’t they romance that opens at an English boarding school. Oh they will (have sex, that is), before the one-third point, but the lingering questions are: will Sidney Ellwood and Henry Gaunt both acknowledge this is love and not just sex, as it is for many teenage boys at their school (either consensually, as buddies; or forced by bullies); and will one or both survive the war? “It was ridiculous, incongruous for Ellwood to be bandying about words like ‘love’ when they were preparing to venture out into No Man’s Land.”

Winn is barely past 30 (and looks like a Victorian waif in her daguerreotype-like author photo), yet keeps a tight control of her tone and plot in this debut novel. She depicts the full horror of war, with detailed accounts of battles at Loos, Ypres and the Somme, and the mental health effects on soldiers, but in between there is light-heartedness: banter, friendship, poetry. Some moments are downright jolly. I couldn’t help but laugh at the fact that Adam Bede is the only novel available and most of them have read it four times. Gaunt is always the more pessimistic of the two, while Ellwood’s initially flippant sunniness darkens through what he sees and suffers.

I only learned from the Acknowledgements and Historical Note that Preshute is based on Marlborough College, a posh school local to me that Winn attended, and that certain particulars are drawn from Siegfried Sassoon, as well as other war literature. It’s clear the book has been thoroughly, even obsessively, researched. But Winn has a light touch with it, and characters who bring social issues into the narrative aren’t just 2D representatives of them but well rounded and essential: Gaunt (xenophobia), Ellwood (antisemitism), Hayes (classism), Devi (racism); not to mention disability and mental health for several.

I also loved how Ellwood is devoted to Tennyson and often quotes from his work, including the book-length elegy In Memoriam itself. This plus the “In Memoriam” columns of the school newspaper give the title extra resonance. I thought I was done with war fiction, but really what I was done with was worthy, redundant Faulks-ian war fiction. This was engaging, thrilling (a prison escape!), and, yes, romantic. (Public library)

Readalike: The New Life by Tom Crewe, another of my early favourites of 2023, is set in a similar time period and also considers homosexual relationships. It, too, has epistolary elements and feels completely true to the historical record.

Some favourite lines:

“If Ellwood were a girl, he might have held his hand, kissed his temple. He might have bought a ring and tied their lives together. But Ellwood was Ellwood, and Gaunt had to be satisfied with the weight of his head on his shoulder.”

“Gaunt wished the War had been what Ellwood wanted it to be. He wished they could have ridden across a battlefield on horseback, brandishing a sword alongside their gallant king. He put on his gas mask. His men followed.”

Buy In Memoriam from Bookshop.org [affiliate link]

Event

Winn is in the UK on a short book tour; although she is English, she now lives in Brooklyn and recently had a baby. She was in conversation with AJ West, the author of The Spirit Engineer, also set on the cusp of WWI. Unrecognizable from her author photo – now blonde with glasses – she is petite rather than willowy. As I was leaving, two ladies remarked to each other how articulate she was. Indeed, she was well spoken and witty and, I expect, has always been precocious and a high achiever. I think she’s 32. Before this she wrote three novels that remain unpublished. She amazed us all by admitting she wrote the bulk of In Memoriam in just two weeks, pausing only to research trench warfare, then edited it for a year and a half.

West asked her about the genesis of the novel and she explained her obsession with the wartime newspapers of Sassoon’s school and then the letters sent home by soldiers, tracking the shift in tenor from early starry-eyed gallantry to feeling surrounded by death. She noted that it was a struggle for her to find a balance between the horrors of the Front and the fact that these young men come across in their written traces as so funny. She got that balance just right.

Was she being consciously anti-zeitgeist in focusing on privileged white men rather than writing women and minorities back into the narrative, as is so popular with publishers today, West asked? She demurred, but added that she wanted to achieve something midway between being of that time and a 2023 point-of-view in terms of the sexuality. Reading between the lines and from secondary sources, she posited that it was perhaps easier to get away with homosexuality than one might think, in that it wasn’t expected and so long as it was secret, temporary (before marrying a woman), or an experiment, it was tolerated. However, she took poetic licence in giving Gaunt and Ellwood supportive friends.

Speaking of … West (a gay man) jokingly asked Winn if she is actually a gay man, because she got their experiences and feelings spot on. She said that she has some generous friends who helped her with the authenticity of the sex scenes. In the novel she has Ellwood interpret Tennyson’s In Memoriam as crypto-homosexual, but scholars do not believe that it is; Gaunt’s twin sister Maud also, unconsciously in that case, has a Tennysonian name. This was in response to an audience question; this plus another one asking if Winn had read The New Life reassured me that my reaction was well founded! (Yes, she has, and will in fact be in conversation with Crewe in London on the 23rd. She’s also appearing at Hay Festival.)

If you’ve read the book and/or are curious, Winn revealed the inspirations for her three main characters, the real people who are “in their DNA,” as she put it: Gaunt = Robert Graves (half-German, interest in the Greek classics); Ellwood = Sassoon; Maud = Vera Brittain. She read a 5-minute passage incorporating a school scene between Gaunt and Sandys and a letter from the Front. She spoke a little too quickly and softly, such that I was glad I was within the first few rows. However, I’m sure this is a new-author thing and, should you be so lucky as to see her speak in future, you will be as impressed as I was.

In keeping with the title, there are environmentalist considerations and musings on materials, but also the connotation of reusing language or rehashing ideas. I appreciated this strategy when he’s pondering etymology (“Strange noun full of verb, noun / bending to verb, strange / idea of repeating repetition” in the title poem) or reworking proverbs in the hilarious “Poem in Which Is Is Sufficient” (“Sufficient unto the glaze / is the primer thereunder. Sufficient / unto the applecart is the upset / thereof” and so on) but perhaps less so during 22 indulgent pages of epigraphs. The distance-designated poems of the inventive “Solvitur Ambulando” section range from history to science fiction: “Abstracted, ankle deep in the proto-gutters of Elizabethan London: / how were you ejected from your life to wash up here?”

In keeping with the title, there are environmentalist considerations and musings on materials, but also the connotation of reusing language or rehashing ideas. I appreciated this strategy when he’s pondering etymology (“Strange noun full of verb, noun / bending to verb, strange / idea of repeating repetition” in the title poem) or reworking proverbs in the hilarious “Poem in Which Is Is Sufficient” (“Sufficient unto the glaze / is the primer thereunder. Sufficient / unto the applecart is the upset / thereof” and so on) but perhaps less so during 22 indulgent pages of epigraphs. The distance-designated poems of the inventive “Solvitur Ambulando” section range from history to science fiction: “Abstracted, ankle deep in the proto-gutters of Elizabethan London: / how were you ejected from your life to wash up here?” Curtis’s four poems are, together, the strongest entry. I particularly loved the final lines of “September Birth”: “We listen close but cannot fathom / Your new language. We will spend / The rest of our days learning it.” Naomi Booth, too, zeroes in on language in “What is tsunami?” A daughter’s acquisition of language provides entertainment (“She names her favourite doll, Hearty Campfire”) but also induces apprehension:

Curtis’s four poems are, together, the strongest entry. I particularly loved the final lines of “September Birth”: “We listen close but cannot fathom / Your new language. We will spend / The rest of our days learning it.” Naomi Booth, too, zeroes in on language in “What is tsunami?” A daughter’s acquisition of language provides entertainment (“She names her favourite doll, Hearty Campfire”) but also induces apprehension: Rebecca Goss’s fourth poetry collection arises from a rural upbringing in Suffolk. Her parents’ farm was a “[s]emi-derelict, ramshackle whimsy of a place”. There’s nostalgia for the countryside left behind and for a less complicated family life before divorce, yet this is no carefree pastoral. From the omnipresent threats to girls to the challenges of motherhood, Goss is awake to the ways in which women are compelled to adapt to life in male spheres. The title/cover image has multiple connotations: the first bond between mother and child; the gates and doors that showcase craftsmanship (as in “Blacksmith, Making”) or seek to shut menacing forces out (see “The Hounds”), but cannot ensure safety.

Rebecca Goss’s fourth poetry collection arises from a rural upbringing in Suffolk. Her parents’ farm was a “[s]emi-derelict, ramshackle whimsy of a place”. There’s nostalgia for the countryside left behind and for a less complicated family life before divorce, yet this is no carefree pastoral. From the omnipresent threats to girls to the challenges of motherhood, Goss is awake to the ways in which women are compelled to adapt to life in male spheres. The title/cover image has multiple connotations: the first bond between mother and child; the gates and doors that showcase craftsmanship (as in “Blacksmith, Making”) or seek to shut menacing forces out (see “The Hounds”), but cannot ensure safety.

Stories of motherhood, the quest to find effective treatment in a patriarchal medical system, volunteer citizen science projects (monitoring numbers of dead seabirds, returning beached cetaceans to the water, dissecting fulmar stomachs to assess their plastic content), and studying Shetland’s history and customs mingle in a fascinating way. Huband travels around the archipelago and further afield, finding a vibrant beachcombing culture on the Dutch island of Texel. As in

Stories of motherhood, the quest to find effective treatment in a patriarchal medical system, volunteer citizen science projects (monitoring numbers of dead seabirds, returning beached cetaceans to the water, dissecting fulmar stomachs to assess their plastic content), and studying Shetland’s history and customs mingle in a fascinating way. Huband travels around the archipelago and further afield, finding a vibrant beachcombing culture on the Dutch island of Texel. As in  And this despite the fact that four of five chapter headings suggest pandemic-specific encounters with nature. Lockdown walks with his two children, and the totems they found in different habitats – also including a chaffinch nest and an owl pellet – are indeed jumping-off points, punctuating a wide-ranging account of life with nature. Smyth surveys the gateway experiences, whether books or television shows or a school tree-planting programme or collecting, that get young people interested; and talks about the people who beckon us into greater communion – sometimes authors and celebrities; other times friends and family. He also engages with questions of how to live in awareness of climate crisis. He acknowledges that he should be vegetarian, but isn’t; who does not harbour such everyday hypocrisies?

And this despite the fact that four of five chapter headings suggest pandemic-specific encounters with nature. Lockdown walks with his two children, and the totems they found in different habitats – also including a chaffinch nest and an owl pellet – are indeed jumping-off points, punctuating a wide-ranging account of life with nature. Smyth surveys the gateway experiences, whether books or television shows or a school tree-planting programme or collecting, that get young people interested; and talks about the people who beckon us into greater communion – sometimes authors and celebrities; other times friends and family. He also engages with questions of how to live in awareness of climate crisis. He acknowledges that he should be vegetarian, but isn’t; who does not harbour such everyday hypocrisies?