First Four in a Row: Márai, Maupin, McEwan, McKay

I announced a few new TBR reading projects back in May 2020, including a Four in a Row Challenge (see the ‘rules’, such as they are, in my opening post). It only took me, um, nearly 11 months to complete a first set! The problem was that I kept changing my mind on which four to include and acquiring more that technically should go into the sequence, e.g. McCracken, McGregor; also, I stalled on the Maupin for ages. But here we are at last. Debbie, meanwhile, took up the challenge and ran with it, completing a set of four novels – also by M authors, clearly a numerous and tempting bunch – back in October. Here’s hers.

I’m on my way to completing a few more sets: I’ve read one G, one and a bit H, and I selected a group of four L. I’ve not chosen a nonfiction quartet yet, but that could be an interesting exercise: I file by author surname even within categories like science/nature and travel, so this could throw up interesting combinations of topics. Do feel free to join in this challenge if, like me, you could use a push to get through more of the books on your shelves.

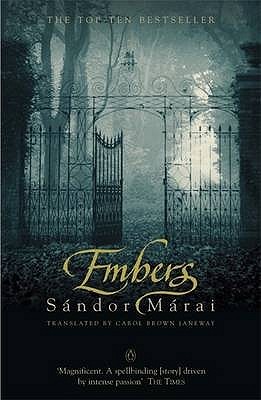

Embers by Sándor Márai (1942)

[Translated from the Hungarian by Carol Brown Janeway]

My first work of Hungarian literature.* This was a random charity shop purchase, simply because I’m always trying to read more international literature and had enjoyed translations by Carol Brown Janeway before. In 1940, two old men are reunited for the first time in 41 years at a gloomy castle, where they will dine by candlelight and, over the course of a long conversation, face up to the secret that nearly destroyed their friendship. This is the residence of 75-year-old Henrik, usually referred to as “the General,” who lives alone apart from Nini, his 91-year-old wet nurse. His wife, Krisztina, died 33 years ago.

My first work of Hungarian literature.* This was a random charity shop purchase, simply because I’m always trying to read more international literature and had enjoyed translations by Carol Brown Janeway before. In 1940, two old men are reunited for the first time in 41 years at a gloomy castle, where they will dine by candlelight and, over the course of a long conversation, face up to the secret that nearly destroyed their friendship. This is the residence of 75-year-old Henrik, usually referred to as “the General,” who lives alone apart from Nini, his 91-year-old wet nurse. His wife, Krisztina, died 33 years ago.

Henrik was 10 when he met Konrad at an academy school. They were soon the best of friends, but two things came between them: first was the difference in their backgrounds (“each forgave the other’s original sin: wealth on the one hand and poverty on the other”); second was their love for the same woman.

I appreciated the different setup to this one – a male friendship, just a few very old characters, the probing of the past through memory and dialogue – but it was so languid that I struggled to stay engaged with the plot.

*My next will be Journey by Moonlight by Antal Szerb, another charity shop find.

Favourite lines:

“My homeland was a feeling, and that feeling was mortally wounded.”

“Life becomes bearable only when one has come to terms with who one is, both in one’s own eyes and in the eyes of the world.”

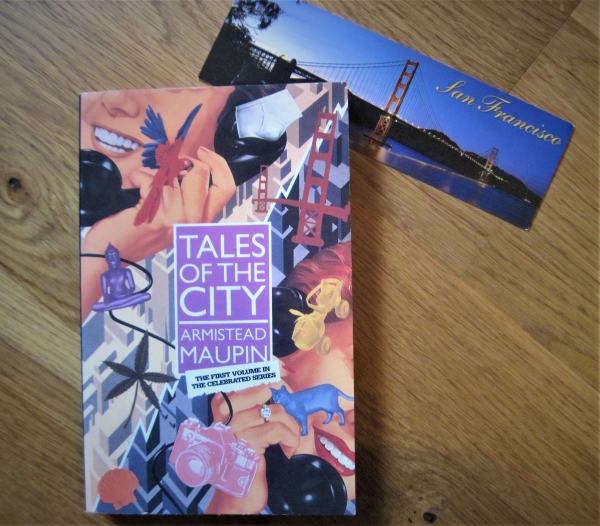

Tales of the City by Armistead Maupin (1978)

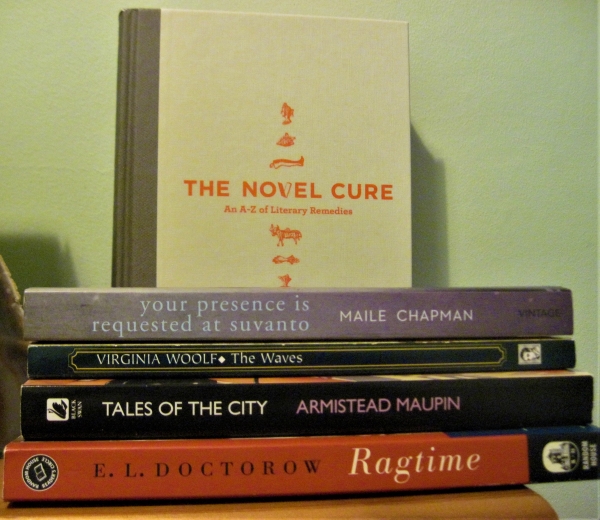

I’d picked this up from the free bookshop we used to have in the local mall (the source of my next two as well) and started it during Lockdown #1 because in The Novel Cure it is given as a prescription for Loneliness. Berthoud and Elderkin suggest it can make you feel like part of a gang of old friends, and it’s “as close to watching television as literature gets” due to the episodic format – the first four Tales books were serialized in the San Francisco Chronicle.

How I love a perfect book and bookmark combination!

The titled chapters are each about three pages long, which made it an ideal bedside book – I would read a chapter per night before sleep. The issue with this piecemeal reading strategy, though, was that I never got to know any of the characters; because I’d often only pick up the book once a week or so, I forgot who people were and what was going on. That didn’t stop individual vignettes from being entertaining, but meant it didn’t all come together for me.

Maupin opens on Mary Ann Singleton, a 25-year-old secretary who goes to San Francisco on vacation and impulsively decides to stay. She rooms at Anna Madrigal’s place on Barbary Lane and meets a kooky assortment of folks, many of them gay – including her new best friend, Michael Tolliver, aka “Mouse.” There are parties and affairs, a pregnancy and a death, all told with a light touch and a clear love for the characters; dialogue predominates. While it’s very much of its time, it manages not to feel too dated overall. I can see why many have taken the series to heart, but don’t think I’ll go further with Maupin’s work.

Note: Long before I tried the book, I knew about it through one of my favourite Bookshop Band songs, “Cleveland,” which picks up on Mary Ann’s sense of displacement as she ponders whether she’d be better off back in Ohio after all. Selected lyrics:

Quaaludes and cocktails

A story book lane

A girl with three names

A place, post-Watergate

Freed from its bird cage

Where the unafraid parade

[…]

Perhaps, we should all

Go back to Cleveland

Where we know what’s around the bend

[…]

Citizens of Atlantis

The Madrigal Enchantress cries

And we decide, to stay and bide our time

On this far-out, far-flung peninsula.

The Children Act by Ian McEwan (2014)

Although it’s good to see McEwan take on a female perspective – a rarer choice for him, though it has shown up in Atonement and On Chesil Beach – this is a lesser novel from him, only interesting insomuch as it combines elements from two of his previous works, The Child in Time (legislation around child welfare) and Enduring Love (a religious stalker). Fiona Maye, a High Court judge, has to decide whether 17-year-old Adam, a bright and musical young man with acute leukaemia, should be treated with blood transfusions despite his Jehovah’s Witness parents’ objection.

Although it’s good to see McEwan take on a female perspective – a rarer choice for him, though it has shown up in Atonement and On Chesil Beach – this is a lesser novel from him, only interesting insomuch as it combines elements from two of his previous works, The Child in Time (legislation around child welfare) and Enduring Love (a religious stalker). Fiona Maye, a High Court judge, has to decide whether 17-year-old Adam, a bright and musical young man with acute leukaemia, should be treated with blood transfusions despite his Jehovah’s Witness parents’ objection.

[SPOILERS FOLLOW]

She rules that the doctors should go ahead with the treatment. “He must be protected from his religion and from himself.” Adam, now better but adrift from the religion he was raised in, starts stalking Fiona and sending her letters and poems. Estranged from her husband, who wants her to condone his affair with a young colleague, and fond of Adam, Fiona spontaneously kisses the young man while traveling for work near Newcastle. But thereafter she ignores his communications, and when he doesn’t seek treatment for his recurring cancer and dies, she blames herself.

[END OF SPOILERS]

It’s worth noting that the AI in McEwan’s most recent full-length novel, Machines Like Me, is also named Adam, and in both books there’s uncertainty about whether the Adam character is supposed to be a child substitute.

The Birth House by Ami McKay (2006)

Dora is the only daughter to be born into the Rare family of Nova Scotia’s Scots Bay in five generations. At age 17, she becomes an apprentice to Marie Babineau, a Cajun midwife and healer who relies on ancient wisdom and appeals to the Virgin Mary to keep women safe and grant them what they want, whether that’s a baby or a miscarriage. As the 1910s advance and the men of the village start leaving for the war, the old ways represented by Miss B. and Dora come to be seen as a threat. Dr. Thomas wants women to take out motherhood insurance and commit to delivering their babies at the new Canning Maternity Home with the help of chloroform and forceps. “Why should you ladies continue to suffer, most notably the trials of childbirth, when there are safe, modern alternatives available to you?” he asks.

Encouraged into marriage at an early age, Dora has to put her vocation on hold to be a wife to Archer Bigelow, a drunkard with big plans for how he’s going to transform the area with windmills that generate electricity. Dora’s narration is interspersed with journal entries, letters, faux newspaper articles, what look like genuine period advertisements, and a glossary of herbal remedies – creating what McKay, in her Author’s Note, calls a “literary scrapbook.” I love epistolary formats, and there are so many interesting themes and appealing secondary characters here. Early obstetrics is not the only aspect of medicine included; there is also an exploration of “hysteria” and its treatment, and the Spanish flu makes a late appearance. Dora, away in Boston at the time, urges her friends from the Occasional Knitters’ Society to block the road to the Bay, make gauze masks, and wash their hands with hot water and soap.

Encouraged into marriage at an early age, Dora has to put her vocation on hold to be a wife to Archer Bigelow, a drunkard with big plans for how he’s going to transform the area with windmills that generate electricity. Dora’s narration is interspersed with journal entries, letters, faux newspaper articles, what look like genuine period advertisements, and a glossary of herbal remedies – creating what McKay, in her Author’s Note, calls a “literary scrapbook.” I love epistolary formats, and there are so many interesting themes and appealing secondary characters here. Early obstetrics is not the only aspect of medicine included; there is also an exploration of “hysteria” and its treatment, and the Spanish flu makes a late appearance. Dora, away in Boston at the time, urges her friends from the Occasional Knitters’ Society to block the road to the Bay, make gauze masks, and wash their hands with hot water and soap.

There are a few places where the narrative is almost overwhelmed by all the (admittedly, fascinating) facts McKay, a debut author, turned up in her research, and where the science versus superstition dichotomy seems too simplistic, but for the most part this was just the sort of absorbing, atmospheric historical fiction that I like best. McKay took inspiration from her own home, an old birthing house in the Bay of Fundy.

Setting up a game of solitaire in The Snow Hare by Paula Lichtarowicz and Of Mice and Men by John Steinbeck.

Setting up a game of solitaire in The Snow Hare by Paula Lichtarowicz and Of Mice and Men by John Steinbeck.

The family’s pet chicken is cooked for dinner in Coleman Hill by Kim Coleman Foote and The Snow Hare by Paula Lichtarowicz.

The family’s pet chicken is cooked for dinner in Coleman Hill by Kim Coleman Foote and The Snow Hare by Paula Lichtarowicz.

A large anonymous donation to a church in Slammerkin by Emma Donoghue and Excellent Women by Barbara Pym (£10–11, which was much more in the 18th century of the former than in the 1950s of the latter).

A large anonymous donation to a church in Slammerkin by Emma Donoghue and Excellent Women by Barbara Pym (£10–11, which was much more in the 18th century of the former than in the 1950s of the latter).

A man throws his tie over his shoulder before eating in Recipe for a Perfect Wife by Karma Brown and Keep by Jenny Haysom.

A man throws his tie over his shoulder before eating in Recipe for a Perfect Wife by Karma Brown and Keep by Jenny Haysom. A scene of self-induced abortion in Recipe for a Perfect Wife by Karma Brown and Sleeping with Cats by Marge Piercy.

A scene of self-induced abortion in Recipe for a Perfect Wife by Karma Brown and Sleeping with Cats by Marge Piercy.

Crossing to Safety with Laila (Big Reading Life)

Crossing to Safety with Laila (Big Reading Life)

Dreams from My Father by Barack Obama: Remember when there was a U.S. president who thought deeply, searched his soul, and wrote eloquently? I first read this memoir in 2006, when Obama was an up-and-coming Democratic politician who’d given a rousing convention speech. I remembered no details, just the general sweep of Hawaii to Chicago to Kenya. On this reread I engaged most with the first third, in which he remembers a childhood in Hawaii and Indonesia, gives pen portraits of his white mother and absentee Kenyan father, and works out what it means to be black and Christian in America. By age 12, he’d stopped advertising his mother’s race, not wanting to ingratiate himself with white people. By contrast, “To be black was to be the beneficiary of a great inheritance, a special destiny, glorious burdens that only we were strong enough to bear.” The long middle section on community organizing in Chicago nearly did me in; I had to skim past it to get to his trip to Kenya to meet his paternal relatives – “Africa had become an idea more than an actual place, a new promised land”.

Dreams from My Father by Barack Obama: Remember when there was a U.S. president who thought deeply, searched his soul, and wrote eloquently? I first read this memoir in 2006, when Obama was an up-and-coming Democratic politician who’d given a rousing convention speech. I remembered no details, just the general sweep of Hawaii to Chicago to Kenya. On this reread I engaged most with the first third, in which he remembers a childhood in Hawaii and Indonesia, gives pen portraits of his white mother and absentee Kenyan father, and works out what it means to be black and Christian in America. By age 12, he’d stopped advertising his mother’s race, not wanting to ingratiate himself with white people. By contrast, “To be black was to be the beneficiary of a great inheritance, a special destiny, glorious burdens that only we were strong enough to bear.” The long middle section on community organizing in Chicago nearly did me in; I had to skim past it to get to his trip to Kenya to meet his paternal relatives – “Africa had become an idea more than an actual place, a new promised land”.

now

now The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot: This Wellcome Book Prize winner about the use of a poor African-American woman’s cells in medical research was one of the first books to turn me onto health-themed reads. I devoured it in a few days in 2010. Once again, I was impressed at the balance between popular science and social history. Skloot conveys the basics of cell biology in a way accessible to laypeople, and uses recreated scenes and dialogue very effectively. I had forgotten the sobering details of the Lacks family experience, including incest, abuse, and STDs. Henrietta had a rural Virginia upbringing and had a child by her first cousin at age 14. At 31 she would be dead of cervical cancer, but the tissue taken from her at Baltimore’s Johns Hopkins hospital became an immortal cell line. HeLa is still commonly used in medical experimentation. Consent was a major talking point at our book club Zoom meeting. Cells, once outside a body, cannot be owned, but it looks like exploitation that Henrietta’s descendants are so limited by their race and poverty. I had forgotten how Skloot’s relationship and travels with Henrietta’s unstable daughter, Deborah, takes over the book (as in the film). While I felt a little uncomfortable with how various family members are portrayed as unhinged, I still thought this was a great read.

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot: This Wellcome Book Prize winner about the use of a poor African-American woman’s cells in medical research was one of the first books to turn me onto health-themed reads. I devoured it in a few days in 2010. Once again, I was impressed at the balance between popular science and social history. Skloot conveys the basics of cell biology in a way accessible to laypeople, and uses recreated scenes and dialogue very effectively. I had forgotten the sobering details of the Lacks family experience, including incest, abuse, and STDs. Henrietta had a rural Virginia upbringing and had a child by her first cousin at age 14. At 31 she would be dead of cervical cancer, but the tissue taken from her at Baltimore’s Johns Hopkins hospital became an immortal cell line. HeLa is still commonly used in medical experimentation. Consent was a major talking point at our book club Zoom meeting. Cells, once outside a body, cannot be owned, but it looks like exploitation that Henrietta’s descendants are so limited by their race and poverty. I had forgotten how Skloot’s relationship and travels with Henrietta’s unstable daughter, Deborah, takes over the book (as in the film). While I felt a little uncomfortable with how various family members are portrayed as unhinged, I still thought this was a great read.  then /

then /  I had some surprising rereading DNFs. These were once favorites of mine, but for some reason I wasn’t able to recapture the magic: Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides, Everything Is Illuminated by Jonathan Safran Foer, Gilead by Marilynne Robinson, and On Beauty by Zadie Smith. I attempted a second read of John Fowles’s postmodern Victorian pastiche, The French Lieutenant’s Woman, on a mini-break in Lyme Regis, happily reading the first third on location, but I couldn’t make myself finish once we were back home. And A Visit from the Goon Squad by Jennifer Egan was very disappointing a second time; it hasn’t aged well. Lastly, I’ve been stalled in Watership Down for a long time, but do intend to finish my reread.

I had some surprising rereading DNFs. These were once favorites of mine, but for some reason I wasn’t able to recapture the magic: Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides, Everything Is Illuminated by Jonathan Safran Foer, Gilead by Marilynne Robinson, and On Beauty by Zadie Smith. I attempted a second read of John Fowles’s postmodern Victorian pastiche, The French Lieutenant’s Woman, on a mini-break in Lyme Regis, happily reading the first third on location, but I couldn’t make myself finish once we were back home. And A Visit from the Goon Squad by Jennifer Egan was very disappointing a second time; it hasn’t aged well. Lastly, I’ve been stalled in Watership Down for a long time, but do intend to finish my reread.

It would have been Richard Adams’s 100th birthday on the 9th. That night I started rereading his classic tale of rabbits in peril, Watership Down, which was my favorite book from childhood even though I only read it the once at age nine. I’m 80 pages in and enjoying all the local place names. Who would ever have predicted that that mousy tomboy from Silver Spring, Maryland would one day live just 6.5 miles from the real Watership Down?!

It would have been Richard Adams’s 100th birthday on the 9th. That night I started rereading his classic tale of rabbits in peril, Watership Down, which was my favorite book from childhood even though I only read it the once at age nine. I’m 80 pages in and enjoying all the local place names. Who would ever have predicted that that mousy tomboy from Silver Spring, Maryland would one day live just 6.5 miles from the real Watership Down?! My husband is joining me for the Watership Down read (he’s not sure he ever read it before), and we’re also doing a buddy read of Arctic Dreams by Barry Lopez. In that case, we ended up with two free copies, one from the bookshop where I volunteer and the other from The Book Thing of Baltimore, so we each have a copy on the go. Lopez’s style, like Peter Matthiessen’s, lends itself to slower, reflective reading, so I’m only two chapters in. It’s novel to journey to the Arctic, especially as we approach the summer.

My husband is joining me for the Watership Down read (he’s not sure he ever read it before), and we’re also doing a buddy read of Arctic Dreams by Barry Lopez. In that case, we ended up with two free copies, one from the bookshop where I volunteer and the other from The Book Thing of Baltimore, so we each have a copy on the go. Lopez’s style, like Peter Matthiessen’s, lends itself to slower, reflective reading, so I’m only two chapters in. It’s novel to journey to the Arctic, especially as we approach the summer.