Wreck by Catherine Newman (and a Cocktail Recipe) for Thanksgiving

Happy Thanksgiving to all who celebrate! Though it’s just an ordinary Thursday here in the UK, I always strive to mark the occasion. Today, it’ll just be with a slice of pumpkin pie. But I’ve also been lucky this year to be invited to two Thanksgiving feasts, the first (vegetarian) last Saturday with a few North American neighbours from my book club and the next one (vegan) coming up tomorrow with university friends, one of whom is half-American. Meal #1 was splendid and kept us fed with leftovers for four days afterwards (I’m sure the second will be equally delicious and bounteous). We contributed mini squashes stuffed with leek and cauliflower macaroni and cheese, mashed potatoes and onion gravy, a pumpkin pie, and nibbles and cocktails. I adapted this pumpkin pie martini for J (too acrid and too sweet for me) but the rest of us had a signature cocktail I invented. Recipe below.

Friendsgiving Berry Cobbler

(Serves 1; or multiply by the number needed!)

50 mL Bombay Bramble gin

20 mL fresh lemon juice

20 mL homemade simple syrup

5 mL Grand Marnier

5 mL cranberry sauce or lingonberry jam

Mix all ingredients with ice in a cocktail shaker, shake well, and strain through a fine sieve to serve. Garnish with fresh cranberries, frozen blackberries and a twist of orange peel. Top up with ginger ale to taste.

Last month I reviewed Wreck by Catherine Newman for Shelf Awareness. It was one of my Most Anticipated books of the second half of the year and has a sequence set on Thanksgiving, which is reason enough to reprint it here.

In Catherine Newman’s third novel, Wreck, a winsome sequel set two years on from Sandwich, a family encounters medical uncertainties and ethical quandaries.

In Catherine Newman’s third novel, Wreck, a winsome sequel set two years on from Sandwich, a family encounters medical uncertainties and ethical quandaries.

Rocky is a fiftysomething food writer and mother of two young adults. After Rocky’s mother’s death, her 92-year-old father moved into the in-law apartment. Rocky and Nick’s son, Jamie, now works as a junior analyst for a New York City consulting firm. The engaging plot turns on two upsetting incidents. “In one single day, in two different directions, my life swerves from its path,” Rocky divulges. First, she notices a mysterious skin rash, which, along with abnormal blood work results, eventually points to an autoimmune liver condition [primary sclerosing cholangitis]; second, news comes that Miles Zapf, one of Jamie’s high school classmates, died in a collision between his car and a train. Was it suicide or an accident? A moral complication arises: Jamie’s firm advised the railroad company.

As one New England fall unfurls, leading to an emotionally climactic Thanksgiving Day, Rocky airs her fears over her prognosis, her father’s infirmity, and her children’s future. Empathy is a two-edged sword—she can’t stop imagining what Miles Zapf’s mother is going through. Newman (We All Want Impossible Things) writes autofiction that’s full of quirky one-liners and particularly resonates with anyone facing mental health and midlife challenges. There’s family drama aplenty, but also the everyday coziness of family rituals, especially those involving food. This warm hug of a novel ponders how to respond graciously when life gets messy and answers aren’t clear-cut.

(Reprinted with permission from Shelf Awareness.)

In short, it’s enjoyable and effortlessly readable, but Rocky is A Bit Much, and after you’ve read Sandwich this is really just more of the same. ![]()

Plus, more Thanksgiving reading ideas in this post I wrote way back in 2015.

Smile: The Story of a Face by Sarah Ruhl

“Ten years ago, my smile walked off my face, and wandered out in the world. This is the story of my asking it to come back.”

Sarah Ruhl is a lauded New York City playwright (Eurydice et al.). These warm and beautifully observed autobiographical essays stem from the birth of her twins and the slow-burning medical crises that followed. Shortly after the delivery, she developed Bell’s palsy, a partial paralysis of the face that usually resolves itself within six months but in rare cases doesn’t go away, and later discovered that she had celiac disease and Hashimoto’s disease, two autoimmune disorders. Having a lopsided face, grimacing and squinting when she tried to show expression on her paralyzed side – she knew this was a minor problem in the grand scheme of things, yet it provoked thorny questions about to what extent the body equates to our identity:

Sarah Ruhl is a lauded New York City playwright (Eurydice et al.). These warm and beautifully observed autobiographical essays stem from the birth of her twins and the slow-burning medical crises that followed. Shortly after the delivery, she developed Bell’s palsy, a partial paralysis of the face that usually resolves itself within six months but in rare cases doesn’t go away, and later discovered that she had celiac disease and Hashimoto’s disease, two autoimmune disorders. Having a lopsided face, grimacing and squinting when she tried to show expression on her paralyzed side – she knew this was a minor problem in the grand scheme of things, yet it provoked thorny questions about to what extent the body equates to our identity:

Can one experience joy when one cannot express joy on one’s face? Does the smile itself create the happiness? Or does happiness create the smile?

As (pretty much) always, I prefer the U.S. cover.

Women are accustomed to men cajoling them into a smile, but now she couldn’t comply even had she wanted to. Ruhl looks into the psychology and neurology of facial expressions, such as the Duchenne smile, but keeps coming back to her own experience: marriage to Tony, a child psychiatrist; mothering Anna and twins William and Hope; teaching and writing and putting on plays; and seeking alternative as well as traditional treatments (acupuncture and Buddhist meditation versus physical therapy; she rejected Botox and experimental surgery) for the Bell’s palsy. By the end of the book she’s achieved about a 70% recovery, but it did take a decade. “A woman slowly gets better. What kind of story is that?” she wryly asks. The answer is: a realistic one. We’re all too cynical these days to believe in miracle cures. But a story of graceful persistence, of setbacks alternating with advances? That’s relatable.

The playwright’s skills are abundantly evident here: strong dialogue and scenes; a clear sense of time, such that flashbacks to earlier life, including childhood, are interlaced naturally; a mixture of exposition and forceful one-liners. She is also brave to include lots of black-and-white family photographs that illustrate the before and after. While reading I often thought of Lucy Grealy’s Autobiography of a Face and Terri Tate’s A Crooked Smile, which are both about life with facial deformity after cancer surgery. I’d also recommend this to readers of Flesh & Blood by N. West Moss, one of my 2021 favourites, and Anne Lamott’s essays on facing everyday life with wit and spiritual wisdom.

More lines I loved:

imperfection is a portal. Whereas perfection and symmetry create distance. Our culture values perfect pictures of ourselves, mirage, over and above authentic connection. But we meet one another through the imperfect particular of our bodies.

Lucky the laugh lines and the smile lines especially: they signify mobility, duration, and joy.

My rating:

With thanks to Bodley Head for the free copy for review.

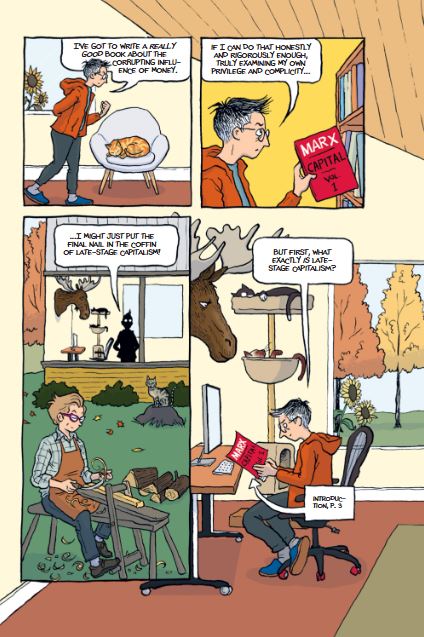

I’ve read all but one of Bechdel’s works now.

I’ve read all but one of Bechdel’s works now.

Nearly a decade ago, I reviewed Peter Kuper’s

Nearly a decade ago, I reviewed Peter Kuper’s

I’d read several of Thompson’s works and especially enjoyed his previous graphic memoir,

I’d read several of Thompson’s works and especially enjoyed his previous graphic memoir,

A decade ago, Barbara Ehrenreich discovered a startling paradox through a Scientific American article: the immune system assists the growth and spread of tumors, including in breast cancer, which she had in 2000. It was an epiphany for her, confirming that no matter how hard we try with diet, exercise and early diagnosis, there’s only so much we can do to preserve our health; “not everything is potentially within our control, not even our own bodies and minds.” I love Ehrenreich’s Smile or Die (alternate title: Bright-Sided), which is what I call an anti-self-help book refuting the supposed health benefits of positive thinking. In that book I felt like her skeptical approach was fully warranted, and I could sympathize with her frustration – nay, outrage – when people tried to suggest she’d attracted her cancer and limited her chances of survival through her pessimism.

A decade ago, Barbara Ehrenreich discovered a startling paradox through a Scientific American article: the immune system assists the growth and spread of tumors, including in breast cancer, which she had in 2000. It was an epiphany for her, confirming that no matter how hard we try with diet, exercise and early diagnosis, there’s only so much we can do to preserve our health; “not everything is potentially within our control, not even our own bodies and minds.” I love Ehrenreich’s Smile or Die (alternate title: Bright-Sided), which is what I call an anti-self-help book refuting the supposed health benefits of positive thinking. In that book I felt like her skeptical approach was fully warranted, and I could sympathize with her frustration – nay, outrage – when people tried to suggest she’d attracted her cancer and limited her chances of survival through her pessimism.

Lents is a biology professor at John Jay College, City University of New York, and in this, his second book, he explores the ways in which the human body is flawed. These errors come in three categories: adaptations to the way the world was for early humans (to take advantage of once-scarce nutrients, we gain weight quickly – but lose it only with difficulty); incomplete adaptations (our knees are still not fit for upright walking); and the basic limitations of our evolution (inefficient systems such as the throat handling both breath and food, and the recurrent laryngeal nerve being three times longer than necessary because it loops around the aorta). Consider that myopia rates are 30% or higher, the retina faces backward, sinuses drain upwards, there are 100+ autoimmune diseases, we have redundant bones in our wrist and ankle, and we can’t produce most of the vitamins we need. Put simply, we’re not a designer’s ideal. And yet this all makes a lot of sense for an evolved species.

Lents is a biology professor at John Jay College, City University of New York, and in this, his second book, he explores the ways in which the human body is flawed. These errors come in three categories: adaptations to the way the world was for early humans (to take advantage of once-scarce nutrients, we gain weight quickly – but lose it only with difficulty); incomplete adaptations (our knees are still not fit for upright walking); and the basic limitations of our evolution (inefficient systems such as the throat handling both breath and food, and the recurrent laryngeal nerve being three times longer than necessary because it loops around the aorta). Consider that myopia rates are 30% or higher, the retina faces backward, sinuses drain upwards, there are 100+ autoimmune diseases, we have redundant bones in our wrist and ankle, and we can’t produce most of the vitamins we need. Put simply, we’re not a designer’s ideal. And yet this all makes a lot of sense for an evolved species.