Three on a Theme of Sylvia Plath (The Slicks by Maggie Nelson for #NonfictionNovember & #NovNov25; The Bell Jar and Ariel)

A review copy of Maggie Nelson’s brand-new biographical essay on Sylvia Plath (and Taylor Swift) was the excuse I needed to finally finish a long-neglected paperback of The Bell Jar and also get a taste of Plath’s poetry through the posthumous collection Ariel, which is celebrating its 60th anniversary. These are the sorts of works it’s hard to believe ever didn’t exist; they feel so fully formed and part of the zeitgeist. It also boggles the mind how much Plath accomplished before her death by suicide at age 30. What I previously knew of her life mostly came from hearsay and was reinforced by Euphoria by Elin Cullhed. For the mixture of nonfiction, fiction and poetry represented below, I’m counting this towards Nonfiction November’s Book Pairings week.

The Slicks: On Sylvia Plath and Taylor Swift by Maggie Nelson (2025)

Can young women embrace fame amidst the other cultural expectations of them? Nelson attempts to answer this question by comparing two figures who turn(ed) life into art. The link between them was strengthened by Swift titling her 2024 album The Tortured Poets Department. “Plath … serves as a metonym – as does Swift – for a woman who makes art about a broken heart,” Nelson writes. “When women make the personal public, the charge of whorishness always lurks nearby.” What women are allowed to say and do has always, it seems, attracted public commentary, and “anyone who puts their work into the world, at any level, must learn to navigate between self-protectiveness and risk, becoming harder and staying soft.”

Can young women embrace fame amidst the other cultural expectations of them? Nelson attempts to answer this question by comparing two figures who turn(ed) life into art. The link between them was strengthened by Swift titling her 2024 album The Tortured Poets Department. “Plath … serves as a metonym – as does Swift – for a woman who makes art about a broken heart,” Nelson writes. “When women make the personal public, the charge of whorishness always lurks nearby.” What women are allowed to say and do has always, it seems, attracted public commentary, and “anyone who puts their work into the world, at any level, must learn to navigate between self-protectiveness and risk, becoming harder and staying soft.”

Nelson acknowledges a major tonal difference between Plath and Swift, however. Plath longed for fame but didn’t get the chance to enjoy it; she’s the patron saint of sad-girl poetry and makes frequent reference to death, whereas Swift spotlights joy and female empowerment. It’s a shame this was out of date before it went to print; my advanced copy, at least, isn’t able to comment on Swift’s engagement and the baby rumour mill sure to follow. It would be illuminating to have an afterword in which Nelson discusses the effect of spouses’ competing fame and speculates on how motherhood might change Swift’s art.

Full confession: I’ve only ever knowingly heard one Taylor Swift song, “Anti-Hero,” on the radio in the States. (My assessment was: wordy, angsty, reasonably catchy.) Undoubtedly, I would have gotten more out of this essay were I equally familiar with the two subjects. Nonetheless, it’s fluid and well argued, and I was engaged throughout. If you’re a Swiftie as well as a literary type, you need to read this.

[66 pages]

With thanks to Vintage (Penguin) for the advanced e-copy for review.

The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath (1963)

Given my love of mental hospital accounts and women’s autofiction, it’s a wonder I’d not read this before my forties. It was first published under the pseudonym “Victoria Lucas” because Plath thought it immature, “an autobiographical apprentice work which I had to write in order to free myself from the past.” Esther Greenwood is the stand-in for Plath: a talented college student who, after working in New York City during the remarkable summer of 1953, plunges into mental ill health. Chapter 13 is amazing and awful at the same time as Esther attempts suicide thrice in one day, toying with a silk bathrobe cord and ocean waves before taking 50 pills and walling herself into a corner of the cellar. She bounces between various institutional settings, undergoing electroshock therapy – the first time it’s horrible, but later, under a kind female doctor, it’s more like it’s ‘supposed’ to be: a calming reset.

Given my love of mental hospital accounts and women’s autofiction, it’s a wonder I’d not read this before my forties. It was first published under the pseudonym “Victoria Lucas” because Plath thought it immature, “an autobiographical apprentice work which I had to write in order to free myself from the past.” Esther Greenwood is the stand-in for Plath: a talented college student who, after working in New York City during the remarkable summer of 1953, plunges into mental ill health. Chapter 13 is amazing and awful at the same time as Esther attempts suicide thrice in one day, toying with a silk bathrobe cord and ocean waves before taking 50 pills and walling herself into a corner of the cellar. She bounces between various institutional settings, undergoing electroshock therapy – the first time it’s horrible, but later, under a kind female doctor, it’s more like it’s ‘supposed’ to be: a calming reset.

The 19-year-old is obsessed with the notion of purity. She has a couple of boyfriends but decides to look for someone else to take her virginity. Beforehand, the asylum doctor prescribes her a fitting for a diaphragm. A defiant claim to the right to contraception despite being unmarried is a way of resisting the bell jar – the rarefied prison – of motherhood. Still, Esther feels guilty about prioritizing her work over what seems like feminine duty: “Why was I so maternal and apart? Why couldn’t I dream of devoting myself to baby after fat puling baby? … I was my own woman.” Plath never reconciled parenthood with poetry. Whether that’s the fault of Ted Hughes, or the times they lived in, who can say. For her and for Esther, the hospital is a prison as well – but not so hermetic as the turmoil of her own mind. How ironic to read “I took a deep breath and listened to the old brag of my heart. I am, I am, I am” knowing that this was published just a few weeks before this literary genius ceased to be.

The 19-year-old is obsessed with the notion of purity. She has a couple of boyfriends but decides to look for someone else to take her virginity. Beforehand, the asylum doctor prescribes her a fitting for a diaphragm. A defiant claim to the right to contraception despite being unmarried is a way of resisting the bell jar – the rarefied prison – of motherhood. Still, Esther feels guilty about prioritizing her work over what seems like feminine duty: “Why was I so maternal and apart? Why couldn’t I dream of devoting myself to baby after fat puling baby? … I was my own woman.” Plath never reconciled parenthood with poetry. Whether that’s the fault of Ted Hughes, or the times they lived in, who can say. For her and for Esther, the hospital is a prison as well – but not so hermetic as the turmoil of her own mind. How ironic to read “I took a deep breath and listened to the old brag of my heart. I am, I am, I am” knowing that this was published just a few weeks before this literary genius ceased to be.

Apart from an unfortunate portrayal of a “negro” worker at the hospital, this was an enduringly relevant and absorbing read, a classic to sit alongside Emily Holmes Coleman’s The Shutter of Snow and Janet Frame’s Faces in the Water.

(Secondhand – it’s been in my collection so long I can’t remember where it’s from, but I’d guess a Bowie Library book sale or Wonder Book & Video / Public library – I was struggling with the small type so switched to a recent paperback and found it more readable)

Ariel by Sylvia Plath (1965)

Impossible not to read this looking for clues of her death to come:

Dying

Is an art, like everything else.

I do it exceptionally well.

(from “Lady Lazarus”)

Eternity bores me,

I never wanted it.

(from “Years”)

The woman is perfected.

Her dead

Body wears the smile of accomplishment

(from “Edge”)

I feel incapable of saying anything fresh about this collection, which takes no prisoners. The images and vocabulary are razor-sharp. First and last lines or stanzas are particularly memorable. (“Morning Song” starts “Love set you going like a fat gold watch”; “Lady Lazarus” ends “Out of the ash / I rise with my red hair / And I eat men like air.”) Words and phrases repeat and gather power as they go. “The Applicant” mocks the obligations of a wife: “A living doll … / It can sew, it can cook. It can talk, talk, talk. … // … My boy, it’s your last resort. / Will you marry it, marry it, marry it.” I don’t know a lot about Plath’s family life, only that her father was a Polish immigrant and died after a long illness when she was eight, but there must have been some daddy issues there – after all, “Daddy” includes the barbs “Daddy, I have had to kill you” and “If I’ve killed one man, I’ve killed two— / The vampire who said he was you / And drank my blood for a year, / Seven years, if you want to know.” It ends, “Daddy, daddy, you bastard, I’m through.” Several later poems in a row, including “Stings,” incorporate bee-related imagery, and Plath’s father was an international bee expert. I can see myself reading this again and again in future, and finding her other collections, too – all but one of them posthumous. (Secondhand – RSPCA charity shop, Newbury)

I feel incapable of saying anything fresh about this collection, which takes no prisoners. The images and vocabulary are razor-sharp. First and last lines or stanzas are particularly memorable. (“Morning Song” starts “Love set you going like a fat gold watch”; “Lady Lazarus” ends “Out of the ash / I rise with my red hair / And I eat men like air.”) Words and phrases repeat and gather power as they go. “The Applicant” mocks the obligations of a wife: “A living doll … / It can sew, it can cook. It can talk, talk, talk. … // … My boy, it’s your last resort. / Will you marry it, marry it, marry it.” I don’t know a lot about Plath’s family life, only that her father was a Polish immigrant and died after a long illness when she was eight, but there must have been some daddy issues there – after all, “Daddy” includes the barbs “Daddy, I have had to kill you” and “If I’ve killed one man, I’ve killed two— / The vampire who said he was you / And drank my blood for a year, / Seven years, if you want to know.” It ends, “Daddy, daddy, you bastard, I’m through.” Several later poems in a row, including “Stings,” incorporate bee-related imagery, and Plath’s father was an international bee expert. I can see myself reading this again and again in future, and finding her other collections, too – all but one of them posthumous. (Secondhand – RSPCA charity shop, Newbury)

#NovNov23 Week 4, “The Short and the Long of It”: W. Somerset Maugham & Jan Morris

Hard to believe, but it’s already the final full week of Novellas in November and we have had 109 posts so far! This week’s prompt is “The Short and the Long of It,” for which we encourage you to pair a novella with a nonfiction book or novel that deals with similar themes or topics. The book pairings week of Nonfiction November is always a favourite (my 2023 contribution is here), so think of this as an adjacent – and hopefully fun – project. I came up with two pairs: one fiction and one nonfiction. In the first case, the longer book led me to read a novella, and it was vice versa for the second.

W. Somerset Maugham

The House of Doors by Tan Twan Eng (2023)

&

Liza of Lambeth by W. Somerset Maugham (1897)

I wasn’t a huge fan of The Garden of Evening Mists, but as soon as I heard that Tan Twan Eng’s third novel was about W. Somerset Maugham, I was keen to read it. Maugham is a reliably readable author; his books are clearly classic literature but don’t pose the stylistic difficulties I now experience with Dickens, Trollope et al. And yet I know that Booker Prize followers who had neither heard of nor read Maugham have enjoyed this equally. I’m surprised it didn’t make it past the longlist stage, as I found it as revealing of a closeted gay writer’s life and times as The Master (shortlisted in 2004) but wider in scope and more rollicking because of its less familiar setting, true crime plot and female narration.

The main action is set in 1921, as “Willie” Somerset Maugham and his secretary, Gerald, widely known to be his lover, rest from their travels in China and the South Seas via a two-week stay with Robert and Lesley Hamlyn at Cassowary House in Penang, Malaysia. Robert and Willie are old friends, and all three men fought in the First World War. Willie’s marriage to Syrie Wellcome (her first husband was the pharmaceutical tycoon) is floundering and he faces financial ruin after a bad investment. He needs a good story that will sell and gets one when Lesley starts recounting to him the momentous events of 1910, including a crisis in her marriage, volunteering at the party office of Chinese pro-democracy revolutionary Dr Sun Yat Sen, and trying to save her friend Ethel Proudlock from a murder charge.

It’s clever how Tan weaves all of this into a Maugham-esque plot that alternates between omniscient third-person narration and Lesley’s own telling. The glimpses of expat life and Asia under colonial rule are intriguing, and the scene-setting and atmosphere are sumptuous – worthy of the Merchant Ivory treatment. I was left curious to read more by and about Maugham, such as Selina Hastings’ biography. (Public library)

But for now I picked up one of the leather-bound Maugham books I got for free a few years ago. Amusingly, the novella-length Liza of Lambeth is printed in the same volume with the travel book On a Chinese Screen, which Maugham had just released when he arrived in Penang.

{SPOILERS AHEAD}

This was Maugham’s debut novel and drew on his time as a medical intern in the slums of London. In tone and content it falls almost perfectly between Dickens and Hardy, because on the one hand Liza Kemp and her neighbours are cheerful paupers even though they work in factories, have too many children and live in cramped quarters; on the other hand, alcoholism and domestic violence are rife, and the wages of sexual sin are death. All seems light to start with: an all-village outing to picnic at Chingford; pub trips; and harmless wooing as Liza rebuffs sweet Tom in favour of a flirtation with married Jim Blakeston.

At the halfway point, I thought we were going full Tess of the d’Urbervilles – how is this not a rape scene?! Jim propositions her four times, ignoring her initial No and later quiet. “‘Liza, will yer?’ She still kept silence, looking away … Suddenly he shook himself, and closing his fist gave her a violent, swinging blow in the belly. ‘Come on,’ he said. And together they slid down into the darkness of the passage.” So starts their affair, which leads to Liza getting beaten up by Mrs Blakeston in the street and then dying of an infection after a miscarriage. The most awful character is Mrs Kemp, who spends the last few pages – while Liza is literally on her deathbed – complaining of her own hardships, congratulating herself on insuring her daughter’s life, and telling a blackly comic story about her husband’s corpse not fitting in his oak coffin and her and the undertaker having to jump on the lid to get it to close.

At the halfway point, I thought we were going full Tess of the d’Urbervilles – how is this not a rape scene?! Jim propositions her four times, ignoring her initial No and later quiet. “‘Liza, will yer?’ She still kept silence, looking away … Suddenly he shook himself, and closing his fist gave her a violent, swinging blow in the belly. ‘Come on,’ he said. And together they slid down into the darkness of the passage.” So starts their affair, which leads to Liza getting beaten up by Mrs Blakeston in the street and then dying of an infection after a miscarriage. The most awful character is Mrs Kemp, who spends the last few pages – while Liza is literally on her deathbed – complaining of her own hardships, congratulating herself on insuring her daughter’s life, and telling a blackly comic story about her husband’s corpse not fitting in his oak coffin and her and the undertaker having to jump on the lid to get it to close.

Liza isn’t entirely the stereotypical whore with the heart of gold, but she is a good-time girl (“They were delighted to have Liza among them, for where she was there was no dullness”) and I wonder if she could even have been a starting point for Eliza Doolittle in Pygmalion. Maugham’s rendering of the cockney accent is over-the-top –

“‘An’ when I come aht,’ she went on, ‘’oo should I see just passin’ the ’orspital but this ’ere cove, an’ ’e says to me, ‘Wot cheer,’ says ’e, ‘I’m goin’ ter Vaux’all, come an’ walk a bit of the wy with us.’ ‘Arright,’ says I, ‘I don’t mind if I do.’”

– but his characters are less caricatured than Dickens’s. And, imagine, even then there was congestion in London:

“They drove along eastwards, and as the hour grew later the streets became more filled and the traffic greater. At last they got on the road to Chingford, and caught up numbers of other vehicles going in the same direction—donkey-shays, pony-carts, tradesmen’s carts, dog-carts, drags, brakes, every conceivable kind of wheeled thing, all filled with people”

In short, this was a minor and derivative-feeling work that I wouldn’t recommend to those new to Maugham. He hadn’t found his true style and subject matter yet. Luckily, there’s plenty of other novels to try. (Free mall bookshop) [159 pages]

Jan Morris

Conundrum by Jan Morris (1974)

&

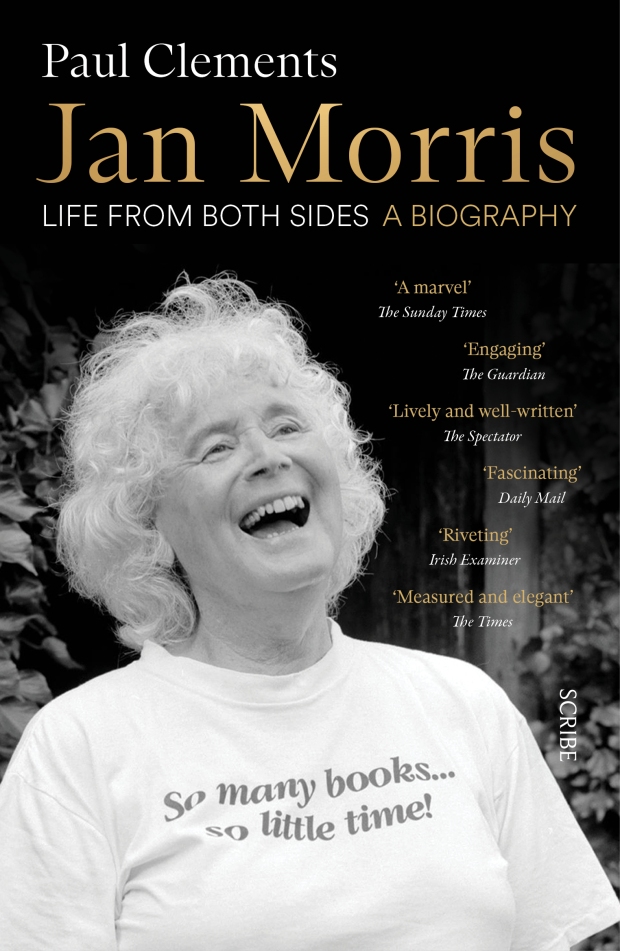

Jan Morris: Life from Both Sides, A Biography by Paul Clements (2022)

Back in 2021, I reread and reviewed Conundrum during Novellas in November. It’s a short memoir that documents her spiritual journey towards her true identity – she was a trans pioneer and influential on my own understanding of gender. In his doorstopper of a biography, Paul Clements is careful to use female pronouns throughout, even when this is a little confusing (with Morris a choirboy, a soldier, an Oxford student, a father, and a member of the Times expedition that first summited Everest). I’m just over a quarter of the way through the book now. Morris left the Times before the age of 30, already the author of several successful travel books on the USA and the Middle East. I’ll have to report back via Love Your Library on what I think of this overall. At this point I feel like it’s a pretty workaday biography, comprehensive and drawing heavily on Morris’s own writings. The focus is on the work and the travels, as well as how the two interacted and influenced her life.

20 Books of Summer, 5: Crudo by Olivia Laing (2018)

Behind on the challenge, as ever, I picked up a novella. It vaguely fits with a food theme as crudo, “raw” in Italian, can refer to fish or meat platters (depicted on the original hardback cover). In this context, though, it connotes the raw material of a life: a messy matrix of choices and random happenings, rooted in a particular moment in time.

This is set over four and a bit months of 2017 and steeped in the protagonist’s detached horror at political and environmental breakdown. She’s just turned 40 and, in between two trips to New York City, has a vacation in Tuscany, dabbles in writing and art criticism, and settles into married life in London even though she’s used to independence and nomadism.

This is set over four and a bit months of 2017 and steeped in the protagonist’s detached horror at political and environmental breakdown. She’s just turned 40 and, in between two trips to New York City, has a vacation in Tuscany, dabbles in writing and art criticism, and settles into married life in London even though she’s used to independence and nomadism.

For as hyper-real as the contents are, Laing is doing something experimental, even fantastical – blending biography with autofiction and cultural commentary by making her main character, apparently, Kathy Acker. Never mind that Acker died of breast cancer in 1997.

I knew nothing of Acker but – while this is clearly born of deep admiration, as well as familiarity with her every written word – that didn’t matter. Acker quotes and Trump tweets are inserted verbatim, with the sources given in a “Something Borrowed” section at the end.

Like Jenny Offill’s Weather, this is a wry and all too relatable take on current events and the average person’s hypocrisy and sense of helplessness, with the lack of speech marks and shortage of punctuation I’ve come to expect from ultramodern novels:

she might as well continue with her small and cultivated life, pick the dahlias, stake the ones that had fallen down, she’d always known whatever it was wasn’t going to last for long.

40, not a bad run in the history of human existence but she’d really rather it all kept going, water in the taps, whales in the oceans, fruits and duvets, the whole sumptuous parade

This is how it is then, walking backwards into disaster, braying all the way.

I’ve somehow read almost all of Laing’s oeuvre (barring her essays, Funny Weather) and have found books like The Trip to Echo Spring, The Lonely City and Everybody wide-ranging and insightful. Crudo feels as faithful to life as Rachel Cusk’s autofiction or Deborah Levy’s autobiography, but also like an attempt to make something altogether new out of the stuff of our unprecedented times. No doubt some of the intertextuality of this, her only fiction to date, was lost on me, but I enjoyed it much more than I expected to – it’s funny as well as eminently quotable – and that’s always a win. (Little Free Library)

I’ve somehow read almost all of Laing’s oeuvre (barring her essays, Funny Weather) and have found books like The Trip to Echo Spring, The Lonely City and Everybody wide-ranging and insightful. Crudo feels as faithful to life as Rachel Cusk’s autofiction or Deborah Levy’s autobiography, but also like an attempt to make something altogether new out of the stuff of our unprecedented times. No doubt some of the intertextuality of this, her only fiction to date, was lost on me, but I enjoyed it much more than I expected to – it’s funny as well as eminently quotable – and that’s always a win. (Little Free Library)

Departure(s) by Julian Barnes [20 Jan., Vintage (Penguin) / Knopf]: (Currently reading) I get more out of rereading Barnes’s classics than reading his latest stuff, but I’ll still attempt anything he publishes. He’s 80 and calls this his last book. So far, it’s heavily about memory. “Julian played matchmaker to Stephen and Jean, friends he met at university in the 1960s; as the third wheel, he was deeply invested in the success of their love”. Sounds way too similar to 1991’s Talking It Over, and the early pages have been tedious. (Review copy from publisher)

Departure(s) by Julian Barnes [20 Jan., Vintage (Penguin) / Knopf]: (Currently reading) I get more out of rereading Barnes’s classics than reading his latest stuff, but I’ll still attempt anything he publishes. He’s 80 and calls this his last book. So far, it’s heavily about memory. “Julian played matchmaker to Stephen and Jean, friends he met at university in the 1960s; as the third wheel, he was deeply invested in the success of their love”. Sounds way too similar to 1991’s Talking It Over, and the early pages have been tedious. (Review copy from publisher) Half His Age by Jennette McCurdy [20 Jan., Fourth Estate / Ballantine]: McCurdy’s memoir, I’m Glad My Mom Died, was stranger than fiction. I was so impressed by her recreation of her childhood perspective on her dysfunctional Mormon/hoarding/child-actor/cancer survivor family that I have no doubt she’ll do justice to this reverse-Lolita scenario about a 17-year-old who’s in love with her schlubby creative writing teacher. (Library copy on order)

Half His Age by Jennette McCurdy [20 Jan., Fourth Estate / Ballantine]: McCurdy’s memoir, I’m Glad My Mom Died, was stranger than fiction. I was so impressed by her recreation of her childhood perspective on her dysfunctional Mormon/hoarding/child-actor/cancer survivor family that I have no doubt she’ll do justice to this reverse-Lolita scenario about a 17-year-old who’s in love with her schlubby creative writing teacher. (Library copy on order) Our Better Natures by Sophie Ward [5 Feb., Corsair]: I loved Ward’s Booker-longlisted

Our Better Natures by Sophie Ward [5 Feb., Corsair]: I loved Ward’s Booker-longlisted  Brawler: Stories by Lauren Groff [Riverhead, Feb. 24]: (Currently reading) Controversial opinion: Short stories are where Groff really shines. Three-quarters in, this collection is just as impressive as Delicate Edible Birds or Florida. “Ranging from the 1950s to the present day and moving across age, class, and region (New England to Florida to California) these nine stories reflect and expand upon a shared the ceaseless battle between humans’ dark and light angels.” (For Shelf Awareness review) (Edelweiss download)

Brawler: Stories by Lauren Groff [Riverhead, Feb. 24]: (Currently reading) Controversial opinion: Short stories are where Groff really shines. Three-quarters in, this collection is just as impressive as Delicate Edible Birds or Florida. “Ranging from the 1950s to the present day and moving across age, class, and region (New England to Florida to California) these nine stories reflect and expand upon a shared the ceaseless battle between humans’ dark and light angels.” (For Shelf Awareness review) (Edelweiss download) Kin by Tayari Jones [24 Feb., Oneworld / Knopf]: I’m a big fan of Leaving Atlanta and An American Marriage. This sounds like Brit Bennett meets Toni Morrison. “Vernice and Annie, two motherless daughters raised in Honeysuckle, Louisiana, have been best friends and neighbors since earliest childhood, but are fated to live starkly different lives. … A novel about mothers and daughters, about friendship and sisterhood, and the complexities of being a woman in the American South”. (Edelweiss download)

Kin by Tayari Jones [24 Feb., Oneworld / Knopf]: I’m a big fan of Leaving Atlanta and An American Marriage. This sounds like Brit Bennett meets Toni Morrison. “Vernice and Annie, two motherless daughters raised in Honeysuckle, Louisiana, have been best friends and neighbors since earliest childhood, but are fated to live starkly different lives. … A novel about mothers and daughters, about friendship and sisterhood, and the complexities of being a woman in the American South”. (Edelweiss download) Almost Life by Kiran Millwood Hargrave [12 March, Picador / March 24, S&S/Summit Books]: There have often been queer undertones in Hargrave’s work, but this David Nicholls-esque plot sounds like her most overt. “Erica and Laure meet on the steps of the Sacré-Cœur in Paris, 1978. … The moment the two women meet the spark is undeniable. But their encounter turns into far more than a summer of love. It is the beginning of a relationship that will define their lives and every decision they have yet to make.” (Edelweiss download)

Almost Life by Kiran Millwood Hargrave [12 March, Picador / March 24, S&S/Summit Books]: There have often been queer undertones in Hargrave’s work, but this David Nicholls-esque plot sounds like her most overt. “Erica and Laure meet on the steps of the Sacré-Cœur in Paris, 1978. … The moment the two women meet the spark is undeniable. But their encounter turns into far more than a summer of love. It is the beginning of a relationship that will define their lives and every decision they have yet to make.” (Edelweiss download) Patient, Female: Stories by Julie Schumacher [May 5, Milkweed Editions]: I found out about this via a webinar with Milkweed and a couple of other U.S. indie publishers. I loved Schumacher’s Dear Committee Members. “[T]his irreverent collection … balances sorrow against laughter. … Each protagonist—ranging from girlhood to senescence—receives her own indelible voice as she navigates social blunders, generational misunderstandings, and the absurdity of the human experience.” The publicist likened the tone to Meg Wolitzer.

Patient, Female: Stories by Julie Schumacher [May 5, Milkweed Editions]: I found out about this via a webinar with Milkweed and a couple of other U.S. indie publishers. I loved Schumacher’s Dear Committee Members. “[T]his irreverent collection … balances sorrow against laughter. … Each protagonist—ranging from girlhood to senescence—receives her own indelible voice as she navigates social blunders, generational misunderstandings, and the absurdity of the human experience.” The publicist likened the tone to Meg Wolitzer. The Things We Never Say by Elizabeth Strout [7 May, Viking (Penguin) / May 5, Random House]: Hurrah for moving on from Lucy Barton at last! “Artie Dam is living a double life. He spends his days teaching history to eleventh graders … and, on weekends, takes his sailboat out on the beautiful Massachusetts Bay. … [O]ne day, Artie learns that life has been keeping a secret from him, one that threatens to upend his entire world. … [This] takes one man’s fears and loneliness and makes them universal.”

The Things We Never Say by Elizabeth Strout [7 May, Viking (Penguin) / May 5, Random House]: Hurrah for moving on from Lucy Barton at last! “Artie Dam is living a double life. He spends his days teaching history to eleventh graders … and, on weekends, takes his sailboat out on the beautiful Massachusetts Bay. … [O]ne day, Artie learns that life has been keeping a secret from him, one that threatens to upend his entire world. … [This] takes one man’s fears and loneliness and makes them universal.” Hunger and Thirst by Claire Fuller [7 May, Penguin / June 2, Tin House]: I’ve read everything of Fuller’s and hope this will reverse the worsening trend of her novels, though true crime is overdone. “1987: After a childhood trauma and years in and out of the care system, sixteen-year-old Ursula … is invited to join a squat at The Underwood. … Thirty-six years later, Ursula is a renowned, reclusive sculptor living under a pseudonym in London when her identity is exposed by true-crime documentary-maker.” (Edelweiss download)

Hunger and Thirst by Claire Fuller [7 May, Penguin / June 2, Tin House]: I’ve read everything of Fuller’s and hope this will reverse the worsening trend of her novels, though true crime is overdone. “1987: After a childhood trauma and years in and out of the care system, sixteen-year-old Ursula … is invited to join a squat at The Underwood. … Thirty-six years later, Ursula is a renowned, reclusive sculptor living under a pseudonym in London when her identity is exposed by true-crime documentary-maker.” (Edelweiss download) Little Vanities by Sarah Gilmartin [21 May, ONE (Pushkin)]: Gilmartin’s Service was great. “Dylan, Stevie and Ben have been inseparable since their days at Trinity, when everything seemed possible. … Two decades on, … Dylan, once a rugby star, is stranded on the sofa, cared for by his wife Rachel. Across town, Stevie and Ben’s relationship has settled into weary routine. Then, after countless auditions, Ben lands a role in Pinter’s Betrayal. As rehearsals unfold, the play’s shifting allegiances seep into reality, reviving old jealousies and awakening sudden longings.”

Little Vanities by Sarah Gilmartin [21 May, ONE (Pushkin)]: Gilmartin’s Service was great. “Dylan, Stevie and Ben have been inseparable since their days at Trinity, when everything seemed possible. … Two decades on, … Dylan, once a rugby star, is stranded on the sofa, cared for by his wife Rachel. Across town, Stevie and Ben’s relationship has settled into weary routine. Then, after countless auditions, Ben lands a role in Pinter’s Betrayal. As rehearsals unfold, the play’s shifting allegiances seep into reality, reviving old jealousies and awakening sudden longings.” Said the Dead by Doireann Ní Ghríofa [21 May, Faber / Sept. 22, Farrar, Straus and Giroux]: A Ghost in the Throat was brilliant and this sounds right up my street. “In the city of Cork, a derelict Victorian mental hospital is being converted into modern apartments. One passerby has always flinched as she passes the place. Had her birth occurred in another decade, she too might have lived within those walls. Now, … she finds herself drawn into an irresistible river of forgotten voices”.

Said the Dead by Doireann Ní Ghríofa [21 May, Faber / Sept. 22, Farrar, Straus and Giroux]: A Ghost in the Throat was brilliant and this sounds right up my street. “In the city of Cork, a derelict Victorian mental hospital is being converted into modern apartments. One passerby has always flinched as she passes the place. Had her birth occurred in another decade, she too might have lived within those walls. Now, … she finds herself drawn into an irresistible river of forgotten voices”. John of John by Douglas Stuart [21 May, Picador / May 5, Grove Press]: I DNFed Shuggie Bain and haven’t tried Stuart since, but the Outer Hebrides setting piqued my attention. “[W]ith little to show for his art school education, John-Calum Macleod takes the ferry back home to the island of Harris [and] begrudgingly resumes his old life, stuck between the two poles of his childhood: his father John, a sheep farmer, tweed weaver, and pillar of their local Presbyterian church, and his maternal grandmother Ella, a profanity-loving Glaswegian”. (For early Shelf Awareness review) (Edelweiss download)

John of John by Douglas Stuart [21 May, Picador / May 5, Grove Press]: I DNFed Shuggie Bain and haven’t tried Stuart since, but the Outer Hebrides setting piqued my attention. “[W]ith little to show for his art school education, John-Calum Macleod takes the ferry back home to the island of Harris [and] begrudgingly resumes his old life, stuck between the two poles of his childhood: his father John, a sheep farmer, tweed weaver, and pillar of their local Presbyterian church, and his maternal grandmother Ella, a profanity-loving Glaswegian”. (For early Shelf Awareness review) (Edelweiss download) Land by Maggie O’Farrell [2 June, Tinder Press / Knopf]: I haven’t fully loved O’Farrell’s shift into historical fiction, but I’m still willing to give this a go. “On a windswept peninsula stretching out into the Atlantic, Tomás and his reluctant son, Liam [age 10], are working for the great Ordnance Survey project to map the whole of Ireland. The year is 1865, and in a country not long since ravaged and emptied by the Great Hunger, the task is not an easy one.” (Edelweiss download)

Land by Maggie O’Farrell [2 June, Tinder Press / Knopf]: I haven’t fully loved O’Farrell’s shift into historical fiction, but I’m still willing to give this a go. “On a windswept peninsula stretching out into the Atlantic, Tomás and his reluctant son, Liam [age 10], are working for the great Ordnance Survey project to map the whole of Ireland. The year is 1865, and in a country not long since ravaged and emptied by the Great Hunger, the task is not an easy one.” (Edelweiss download) Whistler by Ann Patchett [2 June, Bloomsbury / Harper]: Patchett is hella reliable. “When Daphne Fuller and her husband Jonathan visit the Metropolitan Museum of Art, they notice an older, white-haired gentleman following them. The man turns out to be Eddie Triplett, her former stepfather, who had been married to her mother for a little more than year when Daphne was nine. … Meeting again, time falls away; … [in a story of] adults looking back over the choices they made, and the choices that were made for them.” (Edelweiss download)

Whistler by Ann Patchett [2 June, Bloomsbury / Harper]: Patchett is hella reliable. “When Daphne Fuller and her husband Jonathan visit the Metropolitan Museum of Art, they notice an older, white-haired gentleman following them. The man turns out to be Eddie Triplett, her former stepfather, who had been married to her mother for a little more than year when Daphne was nine. … Meeting again, time falls away; … [in a story of] adults looking back over the choices they made, and the choices that were made for them.” (Edelweiss download) Returns and Exchanges by Kayla Rae Whitaker [2 June, Scribe / May 19, Random House]: Whitaker’s The Animators is one of my favourite novels that hardly anyone else has ever heard of. “A sweeping novel of one [discount department store-owning] Kentucky family’s rise and fall throughout the 1980s—a tragicomic tour de force about love and marriage, parents and [their four] children, and the perils of mixing family with business”. (Edelweiss download)

Returns and Exchanges by Kayla Rae Whitaker [2 June, Scribe / May 19, Random House]: Whitaker’s The Animators is one of my favourite novels that hardly anyone else has ever heard of. “A sweeping novel of one [discount department store-owning] Kentucky family’s rise and fall throughout the 1980s—a tragicomic tour de force about love and marriage, parents and [their four] children, and the perils of mixing family with business”. (Edelweiss download) The Great Wherever by Shannon Sanders [9 July, Viking (Penguin) / July 7, Henry Holt]: Sanders’s linked story collection Company left me keen to follow her career. Aubrey Lamb, 32, is “grieving the recent loss of her father and the end of a relationship.” She leaves Washington, DC for her Black family’s ancestral Tennessee farm. “But the land proves to be a burdensome inheritance … [and] the ghosts of her ancestors interject with their own exasperated, gossipy commentary on the flaws and foibles of relatives living and dead”. (Edelweiss download)

The Great Wherever by Shannon Sanders [9 July, Viking (Penguin) / July 7, Henry Holt]: Sanders’s linked story collection Company left me keen to follow her career. Aubrey Lamb, 32, is “grieving the recent loss of her father and the end of a relationship.” She leaves Washington, DC for her Black family’s ancestral Tennessee farm. “But the land proves to be a burdensome inheritance … [and] the ghosts of her ancestors interject with their own exasperated, gossipy commentary on the flaws and foibles of relatives living and dead”. (Edelweiss download) Country People by Daniel Mason [14 July, John Murray / July 7, Random House]: It doesn’t seem long enough since North Woods for there to be another Mason novel, but never mind. “Miles Krzelewski is … twelve years late with his PhD on Russian folktales … [W]hen his wife Kate accepts a visiting professorship at a prestigious college in the far away forests of Vermont, he decides that this will be his year to finally move forward with his life. … [A] luminous exploration of marriage and parenthood, the nature of belief and the power of stories, and the ways in which we find connection in an increasingly fragmented world.”

Country People by Daniel Mason [14 July, John Murray / July 7, Random House]: It doesn’t seem long enough since North Woods for there to be another Mason novel, but never mind. “Miles Krzelewski is … twelve years late with his PhD on Russian folktales … [W]hen his wife Kate accepts a visiting professorship at a prestigious college in the far away forests of Vermont, he decides that this will be his year to finally move forward with his life. … [A] luminous exploration of marriage and parenthood, the nature of belief and the power of stories, and the ways in which we find connection in an increasingly fragmented world.” It Will Come Back to You: Collected Stories by Sigrid Nunez [14 July, Virago / Riverhead]: Nunez is one of my favourite authors but I never knew she’d written short stories. The blurb reveals very little about them! “Carefully selected from three decades of work … Moving from the momentous to the mundane, Nunez maintains her irrepressible humor, bite, and insight, her expert balance between intimacy and universality, gravity and levity, all while entertainingly probing the philosophical questions we have come to expect, such as: How can we withstand the passage of time? Is memory the greatest fiction?” (Edelweiss download)

It Will Come Back to You: Collected Stories by Sigrid Nunez [14 July, Virago / Riverhead]: Nunez is one of my favourite authors but I never knew she’d written short stories. The blurb reveals very little about them! “Carefully selected from three decades of work … Moving from the momentous to the mundane, Nunez maintains her irrepressible humor, bite, and insight, her expert balance between intimacy and universality, gravity and levity, all while entertainingly probing the philosophical questions we have come to expect, such as: How can we withstand the passage of time? Is memory the greatest fiction?” (Edelweiss download) Exit Party by Emily St. John Mandel [17 Sept., Picador / Sept. 15, Knopf]: The synopsis sounds a bit meh, but in my eyes Mandel can do no wrong. “2031. America is at war with itself, but for the first time in weeks there is some good news: the Republic of California has been declared, the curfew in Los Angeles is lifted, and everyone in the city is going to a party. Ari, newly released from prison, arrives with her friend Gloria … Years later, living a different life in Paris, Ari remains haunted by that night.”

Exit Party by Emily St. John Mandel [17 Sept., Picador / Sept. 15, Knopf]: The synopsis sounds a bit meh, but in my eyes Mandel can do no wrong. “2031. America is at war with itself, but for the first time in weeks there is some good news: the Republic of California has been declared, the curfew in Los Angeles is lifted, and everyone in the city is going to a party. Ari, newly released from prison, arrives with her friend Gloria … Years later, living a different life in Paris, Ari remains haunted by that night.” Black Bear: A Story of Siblinghood and Survival by Trina Moyles [Jan. 6, Pegasus Books]: Out now! “When Trina Moyles was five years old, her father … brought home an orphaned black bear cub for a night before sending it to the Calgary Zoo. … After years of working for human rights organizations, Trina returned to northern Alberta for a job as a fire tower lookout, while [her brother] Brendan worked in the oil sands … Over four summers, Trina begins to move beyond fear and observe the extraordinary essence of the maligned black bear”. (For BookBrowse review) (Review e-copy)

Black Bear: A Story of Siblinghood and Survival by Trina Moyles [Jan. 6, Pegasus Books]: Out now! “When Trina Moyles was five years old, her father … brought home an orphaned black bear cub for a night before sending it to the Calgary Zoo. … After years of working for human rights organizations, Trina returned to northern Alberta for a job as a fire tower lookout, while [her brother] Brendan worked in the oil sands … Over four summers, Trina begins to move beyond fear and observe the extraordinary essence of the maligned black bear”. (For BookBrowse review) (Review e-copy) Moveable Feasts: A Story of Paris in Twenty Meals by Chris Newens [Feb. 3, Pegasus Books; came out in the UK in July 2025 but somehow I missed it!]: I’m a sucker for foodie books and Paris books. A “long-time resident of the historic slaughterhouse quartier Villette takes us on a delightful gastronomic journey around Paris … From Congolese catfish in the 18th to Middle Eastern falafels in the 4th, to the charcuterie served at the libertine nightclubs of Pigalle in the 9th, Newens lifts the lid on the city’s ever-changing, defining, and irresistible food culture.” (Edelweiss download)

Moveable Feasts: A Story of Paris in Twenty Meals by Chris Newens [Feb. 3, Pegasus Books; came out in the UK in July 2025 but somehow I missed it!]: I’m a sucker for foodie books and Paris books. A “long-time resident of the historic slaughterhouse quartier Villette takes us on a delightful gastronomic journey around Paris … From Congolese catfish in the 18th to Middle Eastern falafels in the 4th, to the charcuterie served at the libertine nightclubs of Pigalle in the 9th, Newens lifts the lid on the city’s ever-changing, defining, and irresistible food culture.” (Edelweiss download) Frog: And Other Essays by Anne Fadiman [Feb. 10, Farrar, Straus and Giroux]: Fadiman publishes rarely, and it can be difficult to get hold of her books, but they are always worth it. “Ranging in subject matter from her deceased frog, to archaic printer technology, to the fraught relationship between Samuel Taylor Coleridge and his son Hartley, these essays unlock a whole world—one overflowing with mundanity and oddity—through sly observation and brilliant wit.”

Frog: And Other Essays by Anne Fadiman [Feb. 10, Farrar, Straus and Giroux]: Fadiman publishes rarely, and it can be difficult to get hold of her books, but they are always worth it. “Ranging in subject matter from her deceased frog, to archaic printer technology, to the fraught relationship between Samuel Taylor Coleridge and his son Hartley, these essays unlock a whole world—one overflowing with mundanity and oddity—through sly observation and brilliant wit.” The Beginning Comes after the End: Notes on a World of Change by Rebecca Solnit [March 3, Haymarket Books]: A sequel to Hope in the Dark. Hope is a critically endangered species these days, but Solnit has her eyes open. “While the white nationalist and authoritarian backlash drives individualism and isolation, this new world embraces antiracism, feminism, a more expansive understanding of gender, environmental thinking, scientific breakthroughs, and Indigenous and non-Western ideas, pointing toward a more interconnected, relational world.” (Edelweiss download)

The Beginning Comes after the End: Notes on a World of Change by Rebecca Solnit [March 3, Haymarket Books]: A sequel to Hope in the Dark. Hope is a critically endangered species these days, but Solnit has her eyes open. “While the white nationalist and authoritarian backlash drives individualism and isolation, this new world embraces antiracism, feminism, a more expansive understanding of gender, environmental thinking, scientific breakthroughs, and Indigenous and non-Western ideas, pointing toward a more interconnected, relational world.” (Edelweiss download) Jan Morris: A Life by Sara Wheeler [7 April, Faber / April 14, Harper]: I didn’t get on with the mammoth biography Paul Clements published in 2022 – it was dry and conventional; entirely unfitting for Morris – but hope for better things from a fellow female travel writer. “Wheeler uncovers the complexity of this twentieth-century icon … Drawing on unprecedented access to Morris’s papers as well as interviews with family, friends and colleagues, Wheeler assembles a captivating … story of longing, traveling and never reaching home.” (Edelweiss download)

Jan Morris: A Life by Sara Wheeler [7 April, Faber / April 14, Harper]: I didn’t get on with the mammoth biography Paul Clements published in 2022 – it was dry and conventional; entirely unfitting for Morris – but hope for better things from a fellow female travel writer. “Wheeler uncovers the complexity of this twentieth-century icon … Drawing on unprecedented access to Morris’s papers as well as interviews with family, friends and colleagues, Wheeler assembles a captivating … story of longing, traveling and never reaching home.” (Edelweiss download)

I hadn’t realized that Unless, Shields’s final, Booker-shortlisted novel, arose from one of these stories: “A Scarf.” It took me just two paragraphs to figure it out, based on her narrator’s punning novel title (My Thyme Is Up). I’d also forgotten about the fun Shields pokes at literary snobbishness through her protagonist winning the Offenden Prize, which “recognizes literary quality and honors accessibility”. (There is actually a UK prize that rewards ease of reading, the Goldsboro Books Glass Bell Award.)

I hadn’t realized that Unless, Shields’s final, Booker-shortlisted novel, arose from one of these stories: “A Scarf.” It took me just two paragraphs to figure it out, based on her narrator’s punning novel title (My Thyme Is Up). I’d also forgotten about the fun Shields pokes at literary snobbishness through her protagonist winning the Offenden Prize, which “recognizes literary quality and honors accessibility”. (There is actually a UK prize that rewards ease of reading, the Goldsboro Books Glass Bell Award.) In “Dying for Love,” an early standout for me, three wronged women consider suicide. The vocabulary quickly alerts the reader to a change of time period after each section break. All three decide “Life is a thing to be cherished”. My three favourites, though, were the final three – all slightly cheeky with the focus on sex (and naturism). They were together an excellent way to close the volume, and the Collected Stories. In “The Next Best Kiss,” single mother Sandy meets a new paramour at a conference. She and Todd share garrulousness, and a sexual connection. But he doesn’t’ see the appeal of her biography’s subject, a Gregor Mendel-meets-John Clare type, and she is aghast to learn that he still lives with his mother.

In “Dying for Love,” an early standout for me, three wronged women consider suicide. The vocabulary quickly alerts the reader to a change of time period after each section break. All three decide “Life is a thing to be cherished”. My three favourites, though, were the final three – all slightly cheeky with the focus on sex (and naturism). They were together an excellent way to close the volume, and the Collected Stories. In “The Next Best Kiss,” single mother Sandy meets a new paramour at a conference. She and Todd share garrulousness, and a sexual connection. But he doesn’t’ see the appeal of her biography’s subject, a Gregor Mendel-meets-John Clare type, and she is aghast to learn that he still lives with his mother. “Today Is the Day” stands out for its fable-like setup: “Today is the day the women of our village go out along the highway planting blisterlilies.” With the ritualistic activity and the arcane language, it seems borne out of women’s secret history; if it weren’t for mentions of a few modern things like a basketball court, it could have taken place in medieval times.

“Today Is the Day” stands out for its fable-like setup: “Today is the day the women of our village go out along the highway planting blisterlilies.” With the ritualistic activity and the arcane language, it seems borne out of women’s secret history; if it weren’t for mentions of a few modern things like a basketball court, it could have taken place in medieval times. And my overall favourite, 3) “Fuel for the Fire,” a lovely festive-season story that gets beyond the everything-going-wrong-on-a-holiday stereotypes, even though the oven does play up as the narrator is trying to cook a New Year’s Day goose. The things her widowed father brings along to burn on their open fire – a shed he demolished, lilac bushes he took out because they reminded him of his late wife, bowling pins from a derelict alley – are comical yet sad at base, like so much of the story. “Other people might see something nostalgic or sad, but he took a look and saw fuel.” Fire is a force that, like time, will swallow everything.

And my overall favourite, 3) “Fuel for the Fire,” a lovely festive-season story that gets beyond the everything-going-wrong-on-a-holiday stereotypes, even though the oven does play up as the narrator is trying to cook a New Year’s Day goose. The things her widowed father brings along to burn on their open fire – a shed he demolished, lilac bushes he took out because they reminded him of his late wife, bowling pins from a derelict alley – are comical yet sad at base, like so much of the story. “Other people might see something nostalgic or sad, but he took a look and saw fuel.” Fire is a force that, like time, will swallow everything.

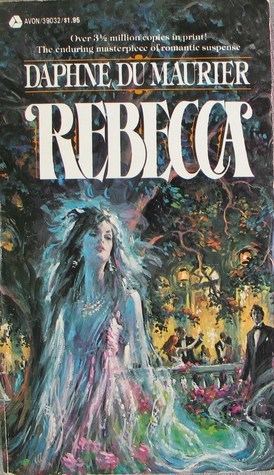

I must have first read this in my early twenties, and remembered it as spooky and atmospheric. I had completely forgotten that the action opens not at Manderley (despite the exceptionally famous first line, which forms part of a prologue-like first chapter depicting the place empty without its master and mistress to tend to it) but in Monte Carlo, where the unnamed narrator meets Maxim de Winter while she’s a lady’s companion to bossy Mrs. Van Hopper. This section functions to introduce Max and his tragic history via hearsay, but I found the first 60 pages so slow that I had trouble maintaining momentum thereafter, especially through the low-action and slightly repetitive scenes as the diffident second Mrs de Winter explores the house and tries to avoid Mrs Danvers, so I ended up skimming most of it.

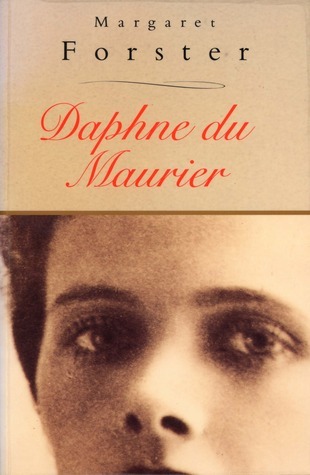

I must have first read this in my early twenties, and remembered it as spooky and atmospheric. I had completely forgotten that the action opens not at Manderley (despite the exceptionally famous first line, which forms part of a prologue-like first chapter depicting the place empty without its master and mistress to tend to it) but in Monte Carlo, where the unnamed narrator meets Maxim de Winter while she’s a lady’s companion to bossy Mrs. Van Hopper. This section functions to introduce Max and his tragic history via hearsay, but I found the first 60 pages so slow that I had trouble maintaining momentum thereafter, especially through the low-action and slightly repetitive scenes as the diffident second Mrs de Winter explores the house and tries to avoid Mrs Danvers, so I ended up skimming most of it. I read my first work by Forster, My Life in Houses, last year, and adored it, so the fact that she was the author was all the more reason to read this when I found a copy in a library secondhand book sale. I started it immediately after our meeting about Rebecca, but I find biographies so dense and daunting that I’m still only a third of the way into it even though I’ve been liberally skimming.

I read my first work by Forster, My Life in Houses, last year, and adored it, so the fact that she was the author was all the more reason to read this when I found a copy in a library secondhand book sale. I started it immediately after our meeting about Rebecca, but I find biographies so dense and daunting that I’m still only a third of the way into it even though I’ve been liberally skimming. Chase of the Wild Goose, a playful, offbeat biographical novel about the Ladies of Llangollen, was first published by Leonard and Virginia Woolf’s Hogarth Press in 1936. I was delighted to be invited to take part in an informal blog tour celebrating the book’s return to print (today, 1 February) as the inaugural publication of

Chase of the Wild Goose, a playful, offbeat biographical novel about the Ladies of Llangollen, was first published by Leonard and Virginia Woolf’s Hogarth Press in 1936. I was delighted to be invited to take part in an informal blog tour celebrating the book’s return to print (today, 1 February) as the inaugural publication of

This exuberant essay, a paean to energy and imagination, draws unexpected connections between two of Hornby’s heroes. Both came from poverty, skyrocketed to fame in their twenties, were astoundingly prolific/workaholic artists, valued performance perhaps more highly than finished products, felt the industry was cheating them, had a weakness for women and died at a similar age. Biographical research shares the page with shrewd cultural commentary and glimpses of Hornby’s writing life. Whether a fan of both subjects, either or none, you’ll surely admire these geniuses’ vitality, too. (Full review forthcoming in the December 30th issue of Shelf Awareness.)

This exuberant essay, a paean to energy and imagination, draws unexpected connections between two of Hornby’s heroes. Both came from poverty, skyrocketed to fame in their twenties, were astoundingly prolific/workaholic artists, valued performance perhaps more highly than finished products, felt the industry was cheating them, had a weakness for women and died at a similar age. Biographical research shares the page with shrewd cultural commentary and glimpses of Hornby’s writing life. Whether a fan of both subjects, either or none, you’ll surely admire these geniuses’ vitality, too. (Full review forthcoming in the December 30th issue of Shelf Awareness.)  In a dozen gritty linked short stories, lovable, flawed characters navigate aging, parenthood, and relationships. Set in Colorado in the recent past, the book depicts a gentrifying area where blue-collar workers struggle to afford childcare and health insurance. As Gus, their boss at St. Anthony Sausage, withdraws their benefits and breaks in response to a recession, it’s unclear whether the business will survive. Each story covers the perspective of a different employee. The connections between tales are subtle. Overall, an endearing composite portrait of a working-class community in transition. (See my

In a dozen gritty linked short stories, lovable, flawed characters navigate aging, parenthood, and relationships. Set in Colorado in the recent past, the book depicts a gentrifying area where blue-collar workers struggle to afford childcare and health insurance. As Gus, their boss at St. Anthony Sausage, withdraws their benefits and breaks in response to a recession, it’s unclear whether the business will survive. Each story covers the perspective of a different employee. The connections between tales are subtle. Overall, an endearing composite portrait of a working-class community in transition. (See my  Pau’s ancestors were part of the South Asian diaspora in East Africa, and later settled in the UK. Her debut, which won one of this year’s Eric Gregory Awards (from the Society of Authors, for a collection by a British poet under the age of 30), reflects on that stew of cultures and languages. Colours and food make up the lush metaphorical palette.

Pau’s ancestors were part of the South Asian diaspora in East Africa, and later settled in the UK. Her debut, which won one of this year’s Eric Gregory Awards (from the Society of Authors, for a collection by a British poet under the age of 30), reflects on that stew of cultures and languages. Colours and food make up the lush metaphorical palette.