Sister Outsider by Audre Lorde (#NovNov25 Buddy Read, #NonfictionNovember)

This year we set two buddy reads for Novellas in November: one contemporary work of fiction (Seascraper) and one classic work of short nonfiction. Do let us know if you’ve been reading them and what you think!

Sister Outsider is a 1984 collection of Audre Lorde’s essays and speeches. Many of these short pieces appeared in Black or radical feminist magazines or scholarly journals, while a few give the text of her conference presentations. Lorde must have been one of the first writers to spotlight intersectionality: she ponders the combined effect of her Black lesbian identity on how she is perceived and what power she has in society.

The title’s paradox draws attention to the push and pull of solidarity and ostracism. She calls white feminists out for not considering what women of colour endure (or for making her a token Black speaker); she decries misogyny in the Black community; and she and her white lover, Frances, seem to attract homophobia from all quarters. Especially while trying to raise her Black teenage son to avoid toxic masculinity, the author comes to realise the importance of “learning to address each other’s difference with respect.”

This is a point she returns to again and again, and it’s as important now as it was when she was writing in the 1970s. So many forms of hatred and discrimination come down to difference being seen as a threat – “I disagree with you, so I must destroy you” is how she caricatures that perspective.

Even if you’ve never read a word that Lorde wrote, you probably know the phrase “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House” – this talk title refers to having to circumvent the racist patriarchy to truly fight oppression. “Revolution is not a one-time event,” she writes in another essay. “It is becoming always vigilant for the smallest opportunity to make a genuine change in established, outgrown responses”.

Even if you’ve never read a word that Lorde wrote, you probably know the phrase “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House” – this talk title refers to having to circumvent the racist patriarchy to truly fight oppression. “Revolution is not a one-time event,” she writes in another essay. “It is becoming always vigilant for the smallest opportunity to make a genuine change in established, outgrown responses”.

My two favourite pieces here also feel like they have entered into the zeitgeist. “Poetry Is Not a Luxury” deems poetry a “necessity for our existence … the way we help give name to the nameless so it can be thought.” And “Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power” is a thrilling redefinition of a holistic sensuality that means living at full tilt and tapping into creativity. “The sharing of joy, whether physical, emotional, psychic, or intellectual, forms a bridge between the sharers which can be the basis for understanding much of what is not shared”.

In some ways this is not an ideal way to be introduced to Lorde’s work, because many of the essays repeat the same themes and reasoning. I made my way through the book very slowly, one piece every day or few days. The speeches would almost certainly be more effective if heard aloud, as intended – and more provocative, too, as they must have undermined other speakers’ assumptions. I was also a bit taken aback by the opening and closing pieces being travelogues: “Notes from a Trip to Russia” is based on journal entries from 1976, while “Grenada Revisited: An Interim Report” about a 1983 trip to her mother’s birthplace. I saw more point to the latter, while the former felt somewhat out of place.

Nonetheless, Lorde’s thinking is essential and ahead of its time. I’d only previously read her short work The Cancer Journals. For years my book club has been toying with reading Zami, her memoir starting with growing up in 1930s Harlem, so I’ll hope to move that up the agenda for next year. Have you read any of her other books that you can recommend?(University library) [190 pages]

Other reviews of Sister Outsider:

Cathy (746 Books)

Marcie (Buried in Print) is making her way through the book one essay at a time. Here’s her latest post.

Seascraper by Benjamin Wood (#NovNov25 Buddy Read)

Seascraper is set in what appears to be the early 1960s yet could easily be a century earlier because of the protagonist’s low-tech career. Thomas Flett lives with his mother in fictional Longferry in northwest England and carries on his grandfather’s tradition of fishing with a horse and cart. Each day he trawls the seabed for shrimp – sometimes twice a day when the tide allows – and sells his catch to local restaurants. At around 20 years old, Thomas still lives with his mother, who is disabled by obesity and chronic pain. He’s the sole breadwinner in the household and there’s an unusual dynamic between them in that his mother isn’t all that many years older, having fallen pregnant by a teacher while she was still in school.

Their life is just a mindless trudge of work with cosy patterns of behaviour in between … He wants to wake up every morning with a better purpose.

It’s a humdrum, hardscrabble existence, and Thomas longs for a bigger and more creative life, which he hopes he might achieve through his folk music hobby – or a chance encounter with an American filmmaker. Edgar Acheson is working on a big-screen adaptation of a novel; to save money, it will be filmed here in Merseyside rather than in coastal Maine where it’s set. One day he turns up at the house asking Thomas to be his guide to the sands. Thomas reluctantly agrees to take Edgar out one evening, even though it will mean missing out on an open mic night. They nearly get lost in the fog and the cart starts to sink into quicksand. What follows is mysterious, almost like a hallucination sequence. When Thomas makes it back home safely, he writes an autobiographical song, “Seascraper” (you can listen to a recording on Wood’s website).

After this one pivotal and surprising day, Thomas’s fortunes might just change. This atmospheric novella contrasts subsistence living with creative fulfillment. There is the bitterness of crushed dreams but also a glimmer of hope. Its The Old Man and the Sea-type setup emphasizes questions of solitude, obsession and masculinity. Thomas wishes he had a father in his life; Edgar, even in so short a time frame, acts as a sort of father figure for him. And Edgar is a father himself – he shows Thomas a photo of his daughter. We are invited to ponder what makes a good father and what the absence of one means at different stages in life. Mental and physical health are also crucial considerations for the characters.

That Wood packs all of this into a compact circadian narrative is impressive. My admiration never crossed into warmth, however. I’ve read four of Wood’s five novels and still love his debut, The Bellwether Revivals, most, followed by his second, The Ecliptic. I’ve also read The Young Accomplice, which I didn’t care for as much, so I’m only missing out on A Station on the Path to Somewhere Better now. Wood’s plot and character work is always at a high standard, but his books are so different from each other that I have no clear sense of him as a novelist. Still, I’m pleased that the Booker longlisting has introduced him to many new readers.

Also reviewed by:

Annabel (AnnaBookBel)

Anne (My Head Is Full of Books)

Brona (This Reading Life)

Cathy (746 Books)

Davida (The Chocolate Lady’s Book Review Blog)

Eric (Lonesome Reader)

Jane (Just Reading a Book)

Helen (She Reads Novels)

Kate (Books Are My Favourite and Best)

Kay (What? Me Read?)

Nancy (The Literate Quilter)

Rachel (Yarra Book Club)

Susan (A life in books)

Check out this written interview with Wood (and this video one with Eric of Lonesome Reader) as well as a Q&A on the Booker Prize website in which Wood talks about the unusual situation in which he wrote the book.

(Public library)

[163 pages]

![]()

Get Ready for Novellas in November!

Novellas: “all killer, no filler”

~Joe Hill

Hard to believe, but it’s nearly that time again. Autumn is drawing in. For the SIXTH year in a row, Cathy of 746 Books and I are co-hosting Novellas in November as a month-long blogging and social media challenge celebrating the art of the short book. A novella technically contains 20,000 to 40,000 words, but to keep things simple we will define it as any work of under 200 pages.

This year we have two buddy reads, a 2025 fiction release and an older work of nonfiction:

Seascraper by Benjamin Wood is set in the early 1960s and features a young man who lives with his mother in northwest England and carries on the family tradition of fishing for shrimp. He longs for a bigger and more creative life, which he hopes he might achieve through his folk music hobby – or his chance encounter with an American filmmaker. On one pivotal day, his fortunes might just change. Check out this interview with Wood to whet your appetite. Last year our buddy read, Orbital, won the Booker Prize, auguring good things for novellas in the public sphere. Seascraper is on the longlist! In this Q&A on the Booker Prize website, Wood talks about the unusual situation in which he wrote it. (160 pages)

Sister Outsider by Audre Lorde is a 1984 collection of short pieces by the late Black lesbian feminist. I’ve only read Lorde’s The Cancer Journals, so I’m looking forward to this. From the Penguin website: “The revolutionary writings of Audre Lorde gave voice to those ‘outside the circle of this society’s definition of acceptable women’. Uncompromising, angry and yet full of hope, this collection of her essential prose – essays, speeches, letters, interviews – explores race, sexuality, poetry, friendship, the erotic and the need for female solidarity, and includes her landmark piece ‘The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House’.” A great opportunity to tie into Nonfiction November. (190 pages)

Please join us in reading one or both books any time between now and the end of November!

You might like to start off the month with a My Year in Novellas retrospective looking at any novellas you have read since last year’s NovNov, and then finish with a New to My TBR list based on what short books others have tempted you with.

It’s always a busy month in the blogging world with Nonfiction November, German Literature Month, Margaret Atwood Reading Month and SciFi Month. Why not search your shelves and/or local library for novellas that could count towards multiple challenges?

From early October a link-up post will be pinned to my site so you can add your planning posts or reviews. Keep in touch via Bluesky (@bookishbeck.bsky.social / @cathybrown746.bsky.social) and Instagram (@bookishbeck / @cathy_746books) and feel free to use the terrific feature images Cathy has made plus our new hashtag, #NovNov25.

Thanks for Joining in with Novellas in November! #NovNov24 Statistics

Co-host Cathy and I are delighted that so many of you participated in Novellas in November again this year and helped us to celebrate the art of the short book. We had 46 participants and 173 posts covering more than 150 books.

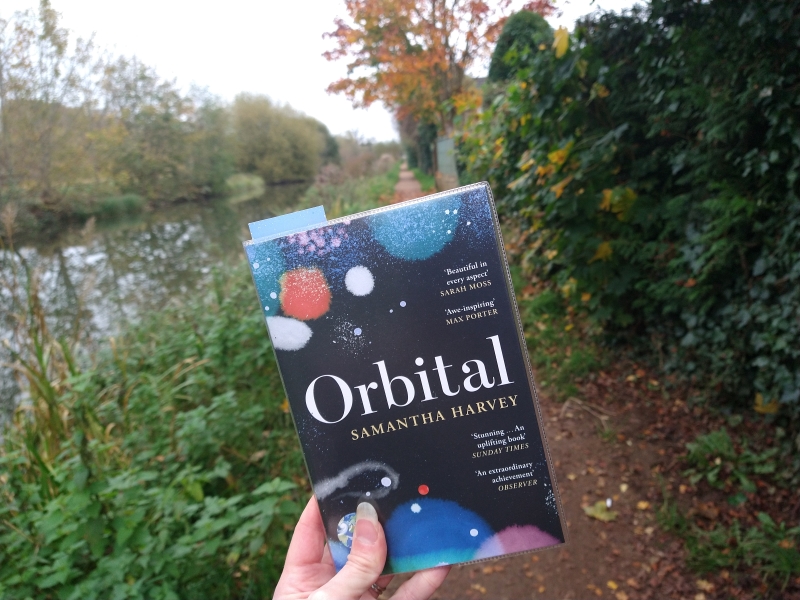

In total, 16 friends of #NovNov reviewed our buddy read, Orbital by Samantha Harvey, which won the Booker Prize partway through the month.

Other books with multiple reviews included John Boyne’s recent novella series, The Party by Tessa Hadley, various by Claire Keegan, Astraea by Kate Kruimink, and Baron Bagge by Alexander Lernet-Holenia.

The link-up will remain open through Saturday 7 December if you would like to add in any belated reviews (I will certainly be doing so).

See you next November – but keep reading novellas and sharing the love all through the year!

#NovNov24 Halfway Check-In & Small Things Like These Film Review

Somehow half of November has flown by. We hope you’ve been enjoying reading and reviewing short books this month. So far we have had 40 participants and 84 posts! Remember to add your posts to the link-up, or alert us via a comment here or on Bluesky (@cathybrown746.bsky.social / @bookishbeck.bsky.social), Instagram (@cathy_746books / @bookishbeck), or X (@cathy746books / @bookishbeck).

If you haven’t already, there’s no better time to pick up our buddy read, Orbital by Samantha Harvey, which won the Booker Prize on Tuesday evening. Chair of judges Edmund de Waal said it is “about a wounded world” and that the panel’s “unanimity about Orbital recognises its beauty and ambition.” I was surprised to learn that it is only the second-shortest Booker winner; Offshore by Penelope Fitzgerald is even shorter.

Another popular novella many of us have read is Small Things Like These by Claire Keegan (my latest review is here). I went to see the excellent film adaptation, with a few friends from book club, at our tiny local arthouse cinema on Wednesday afternoon. I’ve read the book twice now – I might just read it a third time before Christmas – and from memory the film is remarkably faithful to its storyline and scope. (The only significant change I think of is that Bill doesn’t visit Ned in the hospital, but there are still flashbacks to the role that Ned played in Bill’s early life.)

The casting and cinematography are exceptional. Cillian Murphy portrays Bill with just the right blend of stoicism, meekness, and angst. Emily Watson is chilling as Sister Mary, the Mother Superior of the convent, which is suitably creepy with dim brick hallways and clinical laundry rooms. The grimy cobbles and dull streetlamps of the town contrast with the warm light in the scenes of Bill’s remembered childhood at Mrs Wilson’s. Repeated shots – of Bill’s truck setting off across the bridge in the early morning, of him scrubbing coal dust from his hands with carbolic soap, of his eyes wide open in the middle of the night – are not recursive but a way of establishing the gruelling nature of his tasks and the unease that plagues him. A life of physical labour has aged him beyond 39 (cf. Murphy is 48) and he’s in pain from shouldering sacks of coal day in and day out.

The casting and cinematography are exceptional. Cillian Murphy portrays Bill with just the right blend of stoicism, meekness, and angst. Emily Watson is chilling as Sister Mary, the Mother Superior of the convent, which is suitably creepy with dim brick hallways and clinical laundry rooms. The grimy cobbles and dull streetlamps of the town contrast with the warm light in the scenes of Bill’s remembered childhood at Mrs Wilson’s. Repeated shots – of Bill’s truck setting off across the bridge in the early morning, of him scrubbing coal dust from his hands with carbolic soap, of his eyes wide open in the middle of the night – are not recursive but a way of establishing the gruelling nature of his tasks and the unease that plagues him. A life of physical labour has aged him beyond 39 (cf. Murphy is 48) and he’s in pain from shouldering sacks of coal day in and day out.

Both book and film are set in 1985 but apart from the fashions and the kitschy Christmas decorations and window dressings you’d be excused for thinking it was the 1950s. Bill’s business deals in coal, peat and tinder; rural Ireland really was that economically depressed and technologically constrained. (Another Ireland-set film I saw last year, The Miracle Club, is visually very similar – it even features two of the same actors – although it takes place in 1967. It’s as if nothing changed for decades.)

By its nature, the film has to be a little more overt about what Bill is feeling (and generally not saying, as he is such a quiet man): there are tears at Murphy’s eyes and anxious breathing to make Bill’s state of mind obvious. Yet the film retains much of the subtlety of Keegan’s novella. You have to listen carefully during the conversation between Bill and Sister Mary to understand she is attempting to blackmail him into silence about what goes on at the convent.

By its nature, the film has to be a little more overt about what Bill is feeling (and generally not saying, as he is such a quiet man): there are tears at Murphy’s eyes and anxious breathing to make Bill’s state of mind obvious. Yet the film retains much of the subtlety of Keegan’s novella. You have to listen carefully during the conversation between Bill and Sister Mary to understand she is attempting to blackmail him into silence about what goes on at the convent.

At the end of the film showing, you could have heard a pin drop. Everyone was stunned at the simple beauty of the final scene, and the statistics its story is based on. It’s truly astonishing that Magdalene Laundries were in operation until the late 1990s, with Church support. Rage and sorrow build in you at the very thought, but Bill’s quietly heroic act of resistance is an inspiration. What might we, ordinary people all, be called on to do for women, the poor, and the oppressed in the years to come? We have no excuse not to advocate for them.

(Arti of Ripple Effects has also reviewed the film here.)

So far this month I’ve read nine novellas and reviewed eight. One of these was a one-sitting read, and I have another pile of ones that I could potentially read of a morning or evening next week. I’m currently reading another 16 … it remains to be seen whether I will average one a day for the month!

Orbital by Samantha Harvey (#NovNov24 Buddy Read)

Orbital is a circadian narrative, but its one day contains multitudes. Every 90 minutes, a spacecraft completes an orbit of the Earth; the 24 hours the astronauts experience equate to 16 days. And in the same way, this Booker Prize-shortlisted novella contains much more than seems possible for its page length. It plays with scale, zooming from the cosmic down to the human, then back. The situation is simultaneously extraordinary and routine:

Six of them in a great H of metal hanging above the earth. They turn head on heel, four astronauts (American, Japanese, British, Italian) and two cosmonauts (Russian, Russian); two women, four men, one space station made up of seventeen connecting modules, seventeen and a half thousand miles an hour. They are the latest six of many, nothing unusual about this any more[.]

We see these characters – Anton, Roman, Nell, Chie, Shaun, and Pietro – going about daily life as they approach the moon: taking readings, recording data on their health and lab mice’s, exercising, conversing over packaged foods, watching a film, then getting back into the sleeping bags where they started the day. Apart from occasional messages from family, theirs is a completely separate, closed-off existence. Is it magical or claustrophobic? Godlike, they cast benevolent eyes over a whole planet, yet their thoughts are always with the two or three individual humans who mean most to them. A wife, a daughter, a mother who has just died.

Apart from the bereaved astronaut – the one I sympathized with most – I didn’t get a strong sense of the characters as individuals. This may have been deliberate on Harvey’s part, to emphasize how reliant the six are on each other for survival: “we are one. Everything we have up here is only what we reuse and share. … We drink each other’s recycled urine. We breathe each other’s recycled air.” That collectivity and the overt messaging give the book the air of a parable.

Maybe it’s hard to shift from thinking your planet is safe at the centre of it all to knowing in fact it’s a planet of normalish size and normalish mass rotating about an average star in a solar system of average everything in a galaxy of innumerably many, and that the whole thing is going to explode or collapse.

Our lives here are inexpressibly trivial and momentous at once … Both repetitive and unprecedented. We matter greatly and not at all.

Gaining perspective on humankind is always valuable. There is also a strong environmental warning here. “The planet is shaped by the sheer amazing force of human want, which has changed everything, the forests, the poles, the reservoirs, the glaciers, the rivers, the seas, the mountains, the coastlines, the skies”. The astronauts observe climate breakdown firsthand through the inexorable development of a super-typhoon over the Philippines.

There are some stunning lyrical passages (“We exist now in a fleeting bloom of life and knowing, one finger-snap of frantic being … This summery burst of life is more bomb than bud. These fecund times are moving fast”), but Harvey sometimes gets carried away with the sound of words or the sweep of imagery, such that the style threatens to overwhelm the import. This was especially true of the last line. At times, I felt I was watching a BBC nature documentary full of soaring panoramas and time-lapse shots, all choreographed to an ethereal Sigur Rós soundtrack. Am I a cynic for saying so? I confess I don’t think this will win the Booker. But for the most part, I was entranced; grateful for the peek at the immensity of space, the wonder of Earth, and the fragility of human beings. (Public library)

[136 pages]

Mini playlist:

- “Space Walk” by Lemon Jelly

- “Spacewalk” by Bell X1

- “Magic” & “Wonder” by Gungor

- “Hoppípolla” by Sigur Rós

- “Little Astronaut” by Jim Molyneux and Spell Songs

Never fear, others have been more enthusiastic!

Reviewed for this challenge so far by:

A Bag Full of Stories (Susana)

Book Chatter (Tina)

Books Are My Favourite and Best (Kate)

Buried in Print (Marcie)

Calmgrove (Chris)

The Intrepid Angeleno (Jinjer)

My Head Is Full of Books (Anne)

Words and Peace (Emma)

Reviewed earlier by other participants and friends:

Novellas in November 2024 Link-Up (#NovNov24)

Happy November! It’s the fifth year that Cathy of 746 Books and I have been co-hosting Novellas in November. We hope you’ll enjoy reading and reviewing one or more short books this month.

Maybe you’d like to start with a My Year in Novellas retrospective looking back at any novellas you have read since last November (I’ll post mine tomorrow), or you could join in with our Booker Prize-winning buddy read, Orbital by Samantha Harvey.

This post will be pinned to the top of my site all through the month. I’ll add in more link parties as necessary.

Keep in touch via Bluesky (@cathybrown746.bsky.social / @bookishbeck.bsky.social), Instagram (@cathy_746books / @bookishbeck), and X (@cathy746books / @bookishbeck) and do use the feature images plus our new hashtag, #NovNov24.

Have a look at all the posts that have gone up so far!

Get Ready for Novellas in November!

Novellas: “all killer, no filler,” as Joe Hill said. Hard to believe, but it’s now the FIFTH year that Cathy of 746 Books and I have been co-hosting Novellas in November as a month-long blogger/social media challenge celebrating the art of the short book. A novella is a book of 20,000 to 40,000 words, but because that’s hard for a reader to gauge, we tend to say anything under 200 pages (even nonfiction). I’m going to make it a personal challenge to limit myself to books of ~150 pages or less.

We’re keeping it simple this year with just the one buddy read, Orbital by Samantha Harvey. (Though we chose it weeks ago, its shortlisting for the Booker Prize is all the more reason to read it!) The UK hardback has 144 pages. Here’s part of the blurb to entice you:

“Six astronauts rotate in their spacecraft above the earth. … Together they watch their silent blue planet, circling it sixteen times, spinning past continents and cycling through seasons, taking in glaciers and deserts, the peaks of mountains and the swells of oceans. Endless shows of spectacular beauty witnessed in a single day. Yet although separated from the world they cannot escape its constant pull. News reaches them of the death of a mother, and with it comes thoughts of returning home. … They begin to ask, what is life without earth? What is earth without humanity?”

Please join us in reading it at any time between now and the end of November!

We won’t have any official themes or prompts, but you might want to start off the month with a My Year in Novellas retrospective looking at any novellas you have read since last NovNov, and finish it with a New to My TBR list based on what novellas others have tempted you to try in the future.

It’s always a busy month in the blogging world, what with Nonfiction November, German Literature Month, Margaret Atwood Reading Month and SciFi Month. Why not search your shelves and/or local library for novellas that could count towards multiple challenges?

From 1 November there will be a pinned post on my site from which you can join the link-up. Keep in touch via Twitter (@bookishbeck / @cathy746books) and Instagram (@bookishbeck / @cathy_746books), and feel free to use the terrific feature images Cathy has made plus our new hashtag, #NovNov24.

“The Future of the Novella”

On the 11th, at Foyles in London, I attended a perfect event to get me geared up for Novellas in November. Indie publisher Weatherglass Books and judge Ali Smith introduced us to the two winners she chose for the inaugural Weatherglass Novella Prize: Kate Kruimink’s Astraea (set on a 19th-century Australian convict ship), out now, and Deborah Tomkins’ Aerth (a sci-fi novella in flash set on alternative earths), coming out in January.

Ali Smith

We heard readings from both novellas, and Neil Griffiths and Damian Lanigan of Weatherglass told us some more about what they publish and the process of reading the prize submissions (blind!). Lanigan called the novella “a form for our times” and put this down not just to modern attention spans but to focus – the glimpse of something essential. He and Smith mentioned F. Scott Fitzgerald, Claire Keegan, Françoise Sagan and Muriel Spark as some of the masters of the novella form.

The effortlessly cool Smith spoke about the delight of spending weekend mornings – she writes during the week but gives herself the weekends off to read – in bed with a pot of coffee and a Weatherglass novella. She particularly enjoyed going into each book from the shortlist without any context and lamented that blurbs mean the story has to be, to some extent, given away to the reader. She said the ending of a novella has to land “like a cat, on its feet” (Griffiths then appended that it must also be ambiguous).

Kate Kruimink

Kruimink, who edits short stories for a magazine, explained that she thinks of Astraea as a long short story. She wrote it especially for this prize, within two months and for Ali Smith, as it were (she mentioned how formative How to Be Both was for her as a writer). Due to time and word limit constraints, she deliberately crafted a small character arc and didn’t do loads of research, though she had been looking into ships’ surgeons’ journals at the time. She has Irish convict ancestry but noted that this is not uncommon in Tasmania. Astraea is a “sneaky prequel” to her first novel, which has been published in Australia.

Deborah Tomkins

Aerth was originally titled First, Do No Harm, which had the potential to confuse those looking for a medical read. Aerth and Urth are different planets with parallels to our own. The novella tells the story of Magnus, an Everyman on a deeply forested planet heading into an Ice Age. Tomkins first wrote it for the Bath Prize in 2018 and was longlisted, then added to it. She initially sent the book to sci-fi publishers but was told it was not ‘sci-fi enough’.

Griffiths remarked that the shortlist was all-female and that the two winners show how a novella can do many different things: Astraea is at the low end of the word count at 22,000 words and takes place over just 36 hours; Aerth is towards the upper limit at 36,000 words and spans about 40 years.

Neil Griffiths

All the panellists dismissed the idea of a hierarchy with the full-length novel at the top. Griffiths said that the constraints of the novella, to need to discard and discard, make it stand out.

A further title from the 2024 shortlist, We Hexed the Moon by Mollyhall Seeley, will also be published by Weatherglass next year, and submissions are now open for the Weatherglass Novella Prize 2025.

Many thanks for my free ticket to a great event. Weatherglass has also kindly offered to send Cathy and me copies of the two novellas to review over the course of #NovNov. I’m looking forward to reading both winners!

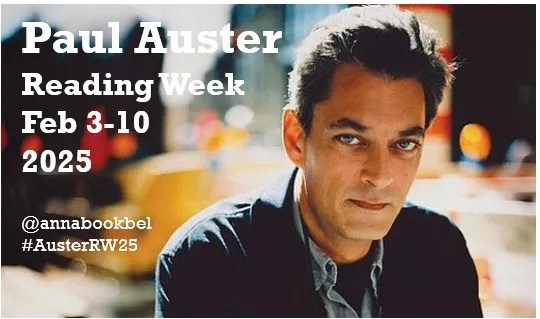

Baumgartner’s past is similar to Auster’s (and Adam Walker’s from Invisible – the two characters have a mutual friend in writer James Freeman), but not identical. His childhood memories and the passion and companionship he found with Anna are quite sweet. But I was somewhat thrown by the tone in sections that have this grumpy older man experiencing pseudo-comic incidents such as tumbling down the stairs while showing the meter reader the way. To my relief, the book doesn’t take the tragic turn the last pages seem to augur, instead leaving readers with a nicely open ending.

Baumgartner’s past is similar to Auster’s (and Adam Walker’s from Invisible – the two characters have a mutual friend in writer James Freeman), but not identical. His childhood memories and the passion and companionship he found with Anna are quite sweet. But I was somewhat thrown by the tone in sections that have this grumpy older man experiencing pseudo-comic incidents such as tumbling down the stairs while showing the meter reader the way. To my relief, the book doesn’t take the tragic turn the last pages seem to augur, instead leaving readers with a nicely open ending. This is very much in the vein of

This is very much in the vein of

The Museum of Whales You Will Never See: Travels among the Collectors of Iceland by A. Kendra Greene (2020) – This sounded quirky and fun, but it turns out it was too niche for me. I read the first two “Galleries” (78 pp.) about the Icelandic Phallological Museum and one woman’s stone collection. Another writer might have used a penis museum as an excuse for lots of cheap laughs, but Greene doesn’t succumb. Still, “no matter how erudite or innocent you imagine yourself to be, you will discover that everything is funnier when you talk about a penis museum. … It’s not salacious. It’s not even funny, except that the joke is on you.” I think I might have preferred a zany Sarah Vowell approach to the material. (Secondhand – Bas Books and Home, Newbury)

The Museum of Whales You Will Never See: Travels among the Collectors of Iceland by A. Kendra Greene (2020) – This sounded quirky and fun, but it turns out it was too niche for me. I read the first two “Galleries” (78 pp.) about the Icelandic Phallological Museum and one woman’s stone collection. Another writer might have used a penis museum as an excuse for lots of cheap laughs, but Greene doesn’t succumb. Still, “no matter how erudite or innocent you imagine yourself to be, you will discover that everything is funnier when you talk about a penis museum. … It’s not salacious. It’s not even funny, except that the joke is on you.” I think I might have preferred a zany Sarah Vowell approach to the material. (Secondhand – Bas Books and Home, Newbury) Because I Don’t Know What You Mean and What You Don’t by Josie Long (2023) – A free signed copy – and, if I’m honest, a cover reminiscent of Ned Beauman’s Glow – induced me to try an author I’d never heard of. She’s a stand-up comic, apparently, not that you’d know it from these utterly boring, one-note stories about unhappy adolescents and mums on London council estates. I read 108 pages but could barely tell you what a single story was about. Long is decent at voices, but you need compelling stories to house them. (Little Free Library)

Because I Don’t Know What You Mean and What You Don’t by Josie Long (2023) – A free signed copy – and, if I’m honest, a cover reminiscent of Ned Beauman’s Glow – induced me to try an author I’d never heard of. She’s a stand-up comic, apparently, not that you’d know it from these utterly boring, one-note stories about unhappy adolescents and mums on London council estates. I read 108 pages but could barely tell you what a single story was about. Long is decent at voices, but you need compelling stories to house them. (Little Free Library)