Carol Shields Prize Longlist: A Council of Dolls by Mona Susan Power

my doll is a collector of tragedy … the device I use to hide from something I already know

Mona Susan Power’s fourth novel, A Council of Dolls, is an Indigenous saga that draws on her own family history. Through first-person narratives by three generations of Dakhóta and Lakhóta women, she explores the ongoing effects of trauma resulting from colonialist oppression. The journey into the past begins with Sissy, a little girl in racist 1960s Chicago with an angry, physically abusive mother, Lillian. This section sets up the book’s pattern of ascribing voice and agency to characters’ dolls. Specifically, Sissy dissociates from her own emotions and upsetting experiences by putting them onto Ethel, her Black doll. Power relies on the dramatic irony between Sissy’s childhood perspective and readers’ understanding.

Moving backward: In 1930s North Dakota, we see Lillian coping with her father’s alcohol-fuelled violence by pretending she is being directed in a play. She loses her Shirley Temple doll, Mae, in an act of charity towards a sickly girl in the community. Lillian and her sister, Blanche, attend an Indian school in Bismarck. Run by nuns, it’s even crueller than the institution their parents, Cora and Jack, attended: the infamous Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania (also a setting in Wandering Stars by Tommy Orange). Cora’s beautifully introspective journal from the 1910s reveals the systematic cultural annihilation that took place there. Her doll, Winona, rescued from a massacre in the time of Sitting Bull, was on the pyre of precious belongings – tribal costumes, instruments, medals, sacred feathers – burned on students’ arrival. But her stone heart survives as a totem of resilience.

This is a powerful but harrowing story. The characterization and narration are strong, and the nesting-dolls structure means we get glimpses into the future for all three protagonists. However, I was disappointed by a number of Power’s decisions. It appeared that a fourth and final narrator close to the present day would introduce another aspect, but in fact Jesse is a new name that Sissy chose for herself. Now a 50-year-old academic and writer, she becomes a medium for the dolls’ accounts – but this ends up repeating material we’d already encountered. The personification of familial tragedy in the figure of “the injured woman” who appears to Cora verges on mawkish, and the touches of magic realism to do with the dolls sit uneasily beside clinical discussions of trauma. In Jesse’s section, there is something unsubtle about how this forms the basis of a conversation between her and her friend Izzy:

(Jesse thinks) “I wanted that chance to break the chain of passing on harmful inner scripts, the self-loathing that comes from brutally effective colonization.”

(Izzy says) “whoo, that’s a big fat pipe full of misery … Our people have been pathologized from the very beginning. Still are.”

It’s possible I would have responded to this with more enthusiasm had it been packaged as a family memoir. As it is, I was unsure about the hybridization of autofiction and magic realism and wondered what white readers coming to the novel should conclude. I kept in mind Elaine Castillo’s essay “How to Read Now,” about her sense of BIPOC writers’ job: “if our stories primarily serve to educate, console and productively scold a comfortable white readership, then those stories will have failed their readers”. Perhaps Power’s novel was not primarily intended to serve in that way.

I’ll let her have the last word, via the Author’s Note: “outrageously prejudiced depictions of my ancestors and our people are one reason I became a writer. From childhood I felt an urgent need to speak my truth, which was long suppressed. Writing this book was a healing endeavor. May it support the healing of others.”

With thanks to publicist Nicole Magas and Mariner Books for the free e-copy for review.

This was a buddy read with Laura; see her review here.

Before the shortlist is announced on 9 April, I plan to review my two current reads, Cocktail by Lisa Alward and Land of Milk and Honey by C Pam Zhang, and concoct a personal wish list.

A Contemporary Classic: Foster by Claire Keegan (#NovNov22)

This year for Novellas in November, Cathy and I chose to host one overall buddy read, Foster by Claire Keegan. I ended up reviewing it for BookBrowse. My full review is here and I also wrote a short related article on Keegan’s career and the unusual publishing history of this particular novella. Here are short excerpts from both:

Claire Keegan’s delicate, heart-rending novella tells the story of a deprived young Irish girl sent to live with rural relatives for one pivotal summer. Although Foster feels like a timeless fable, a brief mention of IRA hunger strikers dates it to 1981. It bears all the hallmarks of a book several times its length: a convincing and original voice, rich character development, an evocative setting, just enough backstory, psychological depth, conflict and sensitive treatment of difficult themes like poverty and neglect. I finished the one-sitting read in a flood of tears, hoping the Kinsellas’ care might be enough to protect the girl from the harshness she may face in the rest of her growing-up years. Keegan unfolds a cautionary tale of endangered childhood, also hinting at the enduring difference a little compassion can make. [128 pages]

Foster is now in print for the first time in the USA (from Grove Atlantic), having had an unusual path to publication. It first appeared in the New Yorker in 2010, but in abridged form. Keegan told the Guardian she felt the condensed version “was very well done but wasn’t the whole story. It had some of the layers taken out, but I think the heart was the same.” She herself has described Foster as a long short story; “It is definitely not a novella. It doesn’t have the pace of a novella.” Faber & Faber first published it as a standalone volume in the UK in 2010. A 2022 Irish-language film version of Foster, called The Quiet Girl (which names the main character Cait) became a favorite on the international film festival circuit.

Foster is now in print for the first time in the USA (from Grove Atlantic), having had an unusual path to publication. It first appeared in the New Yorker in 2010, but in abridged form. Keegan told the Guardian she felt the condensed version “was very well done but wasn’t the whole story. It had some of the layers taken out, but I think the heart was the same.” She herself has described Foster as a long short story; “It is definitely not a novella. It doesn’t have the pace of a novella.” Faber & Faber first published it as a standalone volume in the UK in 2010. A 2022 Irish-language film version of Foster, called The Quiet Girl (which names the main character Cait) became a favorite on the international film festival circuit.

[Edited on December 1st]

A number of you joined us in reading Foster this month:

Lynne at Fictionophile

Karen at The Simply Blog

Davida at The Chocolate Lady’s Book Reviews

Tony at Tony’s Book World

Brona at This Reading Life

Janet at Love Books Read Books

Jane at Just Reading a Book

Kate at Books Are My Favourite and Best

Carol at Reading Ladies

(Cathy also reviewed it last year.)

Our bloggers have been impressed with the spare, precise writing style and the emotional heft of this little tale. Their only complaint? The slight ambiguity of the ending. Read it yourself to find out what you think! If you’d still like to take part in the buddy read and have an hour or two free, remember you can access the original version of the story here.

The dialogue is sparkling, just like you’d expect from a playwright. As in the Hendrik Groen books and Elizabeth Taylor’s Mrs Palfrey at the Claremont, the situation invites cliques and infantilizing. The occasional death provides a bit more excitement than jigsaws and knitting. Ageing bodies may be pitiable (the incontinence!), but sex remains a powerful impulse.

The dialogue is sparkling, just like you’d expect from a playwright. As in the Hendrik Groen books and Elizabeth Taylor’s Mrs Palfrey at the Claremont, the situation invites cliques and infantilizing. The occasional death provides a bit more excitement than jigsaws and knitting. Ageing bodies may be pitiable (the incontinence!), but sex remains a powerful impulse. The 18 poems in this pamphlet (in America it would be called a chapbook) orbit the sudden death of Pimlott’s husband a few years ago. By the time she found Robert at the bottom of the stairs, there was nothing paramedics could do. What next? The callousness of bureaucracy: “Your demise constitutes a quarter off council tax; / the removal of a vote you seldom cast and then / only to be contrary; write-off of a modest overdraft; / the bill for an overpaid pension” (from “Death Admin I”). Attempts at healthy routines: “I’ve written my menu for the week. Today’s chowder. / I manage ten pieces of the 1000-piece jigsaw’s scenes / from Jane Austen. Tomorrow I’ll visit friends and say // it’s alright, it’s alright, seventy, eighty percent / alright” (from “How to be a widow”). Pimlott casts an eye over the possessions he left behind, remembering him in gardens and on Sunday walks of the sort they took together. Grief narratives can err towards bitter or mawkish, but this one never does. Everyday detail, enjambment and sprightly vocabulary lend the wry poems a matter-of-fact grace. I plan to pass on my copy to a new book club member who was widowed unexpectedly in May – no doubt she’ll recognise the practical challenges and emotional reality depicted.

The 18 poems in this pamphlet (in America it would be called a chapbook) orbit the sudden death of Pimlott’s husband a few years ago. By the time she found Robert at the bottom of the stairs, there was nothing paramedics could do. What next? The callousness of bureaucracy: “Your demise constitutes a quarter off council tax; / the removal of a vote you seldom cast and then / only to be contrary; write-off of a modest overdraft; / the bill for an overpaid pension” (from “Death Admin I”). Attempts at healthy routines: “I’ve written my menu for the week. Today’s chowder. / I manage ten pieces of the 1000-piece jigsaw’s scenes / from Jane Austen. Tomorrow I’ll visit friends and say // it’s alright, it’s alright, seventy, eighty percent / alright” (from “How to be a widow”). Pimlott casts an eye over the possessions he left behind, remembering him in gardens and on Sunday walks of the sort they took together. Grief narratives can err towards bitter or mawkish, but this one never does. Everyday detail, enjambment and sprightly vocabulary lend the wry poems a matter-of-fact grace. I plan to pass on my copy to a new book club member who was widowed unexpectedly in May – no doubt she’ll recognise the practical challenges and emotional reality depicted. Ten-year-old Ronja and her teenage sister Melissa have to stick together – their single father may be jolly and imaginative, but more often than not he’s drunk and unemployed. They can’t rely on him to keep food in their Tøyen flat; they subsist on cereal. When Ronja hears about a Christmas tree seller vacancy, she hopes things might turn around. Their father lands the job but, after his crew at a local pub pull him back into bad habits, Melissa has to take over his hours. Ronja hangs out at the Christmas tree stand after school, even joining in enthusiastically with publicity. The supervisor, Tommy, doesn’t mind her being around, but it’s clear that Eriksen, the big boss, is uncomfortable with even a suggestion of child labour.

Ten-year-old Ronja and her teenage sister Melissa have to stick together – their single father may be jolly and imaginative, but more often than not he’s drunk and unemployed. They can’t rely on him to keep food in their Tøyen flat; they subsist on cereal. When Ronja hears about a Christmas tree seller vacancy, she hopes things might turn around. Their father lands the job but, after his crew at a local pub pull him back into bad habits, Melissa has to take over his hours. Ronja hangs out at the Christmas tree stand after school, even joining in enthusiastically with publicity. The supervisor, Tommy, doesn’t mind her being around, but it’s clear that Eriksen, the big boss, is uncomfortable with even a suggestion of child labour. My favourite individual story was “August in the Forest,” about a poet whose artist’s fellowship isn’t all it cracked up to be – the primitive cabin being no match for a New Hampshire winter. His relationships with a hospital doctor, Chloe, and his childhood best friend, Elizabeth, seem entirely separate until Elizabeth returns from Laos and both women descend on him at the cabin. Their dialogues are funny and brilliantly awkward (“Sorry not all of us are quietly chiseling toward the beating heart of the human experience, August. One iamb at a time”) and it’s fascinating to watch how, years later, August turns life into prose. But the crowning achievement is the opening title story and its counterpart, “Origin Stories,” about folk music recordings made by two university friends during the First World War – and the afterlife of both the songs and the men.

My favourite individual story was “August in the Forest,” about a poet whose artist’s fellowship isn’t all it cracked up to be – the primitive cabin being no match for a New Hampshire winter. His relationships with a hospital doctor, Chloe, and his childhood best friend, Elizabeth, seem entirely separate until Elizabeth returns from Laos and both women descend on him at the cabin. Their dialogues are funny and brilliantly awkward (“Sorry not all of us are quietly chiseling toward the beating heart of the human experience, August. One iamb at a time”) and it’s fascinating to watch how, years later, August turns life into prose. But the crowning achievement is the opening title story and its counterpart, “Origin Stories,” about folk music recordings made by two university friends during the First World War – and the afterlife of both the songs and the men.

My last unread book by Ansell (whose

My last unread book by Ansell (whose  At a confluence of Southern, Black and gay identities, Kinard writes of matriarchal families, of congregations and choirs, of the descendants of enslavers and enslaved living side by side. The layout mattered more than I knew, reading an e-copy: often it is white text on a black page; words form rings or an infinity symbol; erasure poems gray out much of what has come before. “Boomerang” interludes imagine a chorus of fireflies offering commentary – just one of numerous insect metaphors. Mythology also plays a role. “A Tangle of Gorgons,” a sample poem I’d read before, wends its serpentine way across several pages. “Catalog of My Obsessions or Things I Answer to” presents an alphabetical list. For the most part, the poems were longer, wordier and more involved (four pages of notes on the style and allusions) than I tend to prefer, but I could appreciate the religious frame of reference and the alliteration.

At a confluence of Southern, Black and gay identities, Kinard writes of matriarchal families, of congregations and choirs, of the descendants of enslavers and enslaved living side by side. The layout mattered more than I knew, reading an e-copy: often it is white text on a black page; words form rings or an infinity symbol; erasure poems gray out much of what has come before. “Boomerang” interludes imagine a chorus of fireflies offering commentary – just one of numerous insect metaphors. Mythology also plays a role. “A Tangle of Gorgons,” a sample poem I’d read before, wends its serpentine way across several pages. “Catalog of My Obsessions or Things I Answer to” presents an alphabetical list. For the most part, the poems were longer, wordier and more involved (four pages of notes on the style and allusions) than I tend to prefer, but I could appreciate the religious frame of reference and the alliteration. “Immanuel was the centre of the world once. Long after it imploded, its gravitational pull remains.” McNaught grew up in an evangelical church in Winchester, England, but by the time he left for university he’d fallen away. Meanwhile, some peers left for Nigeria to become disciples at charismatic preacher TB Joshua’s Synagogue Church of All Nations in Lagos. It’s obvious to outsiders that this was a cult, but not so to those caught up in it. It took years and repeated allegations for people to wake up to faked healings, sexual abuse, and the ceding of control to a megalomaniac who got rich off of duping and exploiting followers. This book won the inaugural Fitzcarraldo Editions Essay Prize. I admired its blend of journalistic and confessional styles: research, interviews with friends and strangers alike, and reflection on the author’s own loss of faith. He gets to the heart of why people stayed: “A feeling of holding and of being held. A sense of fellowship and interdependence … the rare moments of transcendence … It was nice to be a superorganism.” This gripped me from page one, but its wider appeal strikes me as limited. For me, it was the perfect chance to think about how I might write about traditions I grew up in and spurned.

“Immanuel was the centre of the world once. Long after it imploded, its gravitational pull remains.” McNaught grew up in an evangelical church in Winchester, England, but by the time he left for university he’d fallen away. Meanwhile, some peers left for Nigeria to become disciples at charismatic preacher TB Joshua’s Synagogue Church of All Nations in Lagos. It’s obvious to outsiders that this was a cult, but not so to those caught up in it. It took years and repeated allegations for people to wake up to faked healings, sexual abuse, and the ceding of control to a megalomaniac who got rich off of duping and exploiting followers. This book won the inaugural Fitzcarraldo Editions Essay Prize. I admired its blend of journalistic and confessional styles: research, interviews with friends and strangers alike, and reflection on the author’s own loss of faith. He gets to the heart of why people stayed: “A feeling of holding and of being held. A sense of fellowship and interdependence … the rare moments of transcendence … It was nice to be a superorganism.” This gripped me from page one, but its wider appeal strikes me as limited. For me, it was the perfect chance to think about how I might write about traditions I grew up in and spurned. Like other short works I’ve read by Hispanic women authors (

Like other short works I’ve read by Hispanic women authors ( I knew from

I knew from  The epigraph is from the two pages of laughter (“Ha!”) in “Real Estate,” one of the stories of

The epigraph is from the two pages of laughter (“Ha!”) in “Real Estate,” one of the stories of

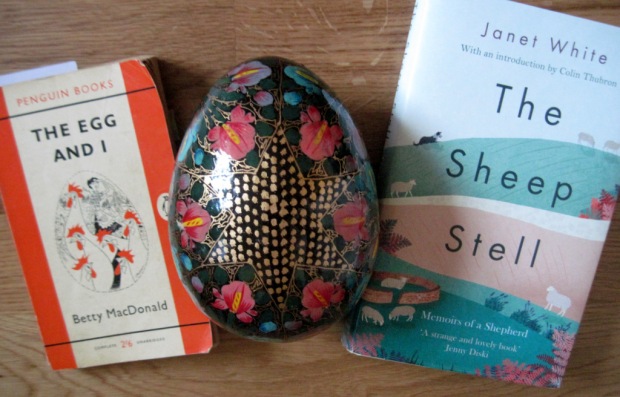

I’m reviewing this reissued memoir for the TLS. It’s a delightful story of finding contentment in the countryside, whether on her own or with family. White, now in her eighties, has been a shepherd for six decades in the British Isles and in New Zealand. While there’s some darker material here about being stalked by a spurned suitor, the tone is mostly lighthearted. I’d recommend it to anyone who’s enjoyed books by Gerald Durrell, James Herriot and Doreen Tovey.

I’m reviewing this reissued memoir for the TLS. It’s a delightful story of finding contentment in the countryside, whether on her own or with family. White, now in her eighties, has been a shepherd for six decades in the British Isles and in New Zealand. While there’s some darker material here about being stalked by a spurned suitor, the tone is mostly lighthearted. I’d recommend it to anyone who’s enjoyed books by Gerald Durrell, James Herriot and Doreen Tovey. Mrs. Creasy disappears one Monday in June 1976, and ten-year-old Grace Bennett and her friend Tilly are determined to figure out what happened. I have a weakness for precocious child detectives (from Harriet the Spy to Flavia de Luce), so I enjoyed Grace’s first-person sections, but it always feels like cheating to me when an author realizes they can’t reveal everything from a child’s perspective so add in third-person narration and flashbacks. These fill in the various neighbors’ sad stories and tell of a rather shocking act of vigilante justice they together undertook nine years ago.

Mrs. Creasy disappears one Monday in June 1976, and ten-year-old Grace Bennett and her friend Tilly are determined to figure out what happened. I have a weakness for precocious child detectives (from Harriet the Spy to Flavia de Luce), so I enjoyed Grace’s first-person sections, but it always feels like cheating to me when an author realizes they can’t reveal everything from a child’s perspective so add in third-person narration and flashbacks. These fill in the various neighbors’ sad stories and tell of a rather shocking act of vigilante justice they together undertook nine years ago.

My first collection from the prolific Pulitzer winner. Some of the poems are built around self-interrogation, with a question and answer format; several reflect on the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice. The first and last poems are both entitled “Vita Nova,” while another in the middle is called “The New Life.” I enjoyed the language of spring in the first “Vita Nova” and in “The Nest,” but I was unconvinced by much of what Glück writes about love and self-knowledge, some of it very clichéd indeed, e.g. “I found the years of the climb upward / difficult, filled with anxiety” (from “Descent to the Valley”) and “My life took me many places, / many of them very dark” (from “The Mystery”).

My first collection from the prolific Pulitzer winner. Some of the poems are built around self-interrogation, with a question and answer format; several reflect on the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice. The first and last poems are both entitled “Vita Nova,” while another in the middle is called “The New Life.” I enjoyed the language of spring in the first “Vita Nova” and in “The Nest,” but I was unconvinced by much of what Glück writes about love and self-knowledge, some of it very clichéd indeed, e.g. “I found the years of the climb upward / difficult, filled with anxiety” (from “Descent to the Valley”) and “My life took me many places, / many of them very dark” (from “The Mystery”).