Best Books of 2025: The Runners-Up

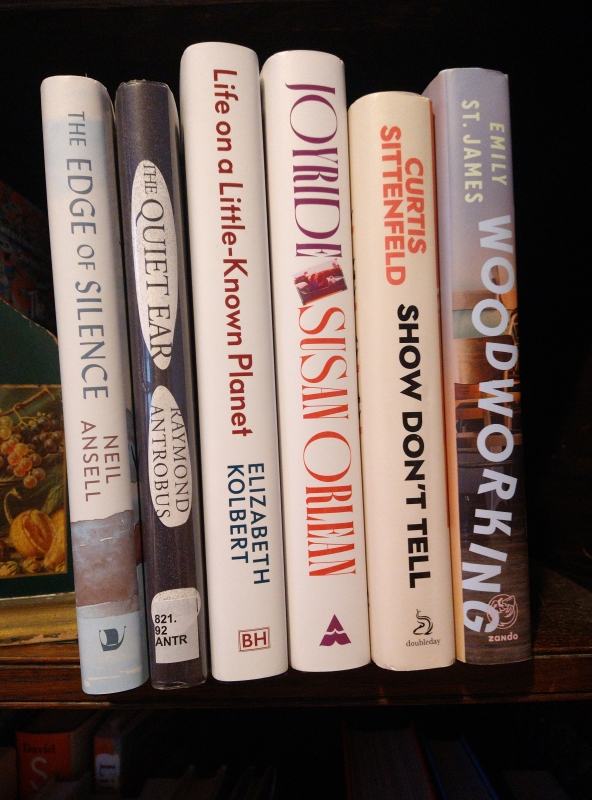

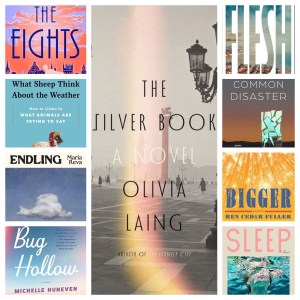

Coming up tomorrow: my list of the 15 best 2025 releases I’ve read. Here are 15 more that nearly made the cut. Pictured below are the ones I read / could get my hands on in print; the rest were e-copies or in-demand library books. Links are to my full reviews where available.

Fiction

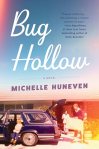

Bug Hollow by Michelle Huneven: A glistening portrait of a lovably dysfunctional California family beset by losses through the years but expanded through serendipity and friendship. Life changes forever for the Samuelsons (architect dad Phil; mom Sibyl, a fourth-grade teacher; three kids) when the eldest son, Ellis, moves into a hippie commune in the Santa Cruz Mountains. A rotating close third-person perspective spotlights each member. Fans of Jami Attenberg, Ann Patchett, and Anne Tyler need to try Huneven’s work pronto.

Bug Hollow by Michelle Huneven: A glistening portrait of a lovably dysfunctional California family beset by losses through the years but expanded through serendipity and friendship. Life changes forever for the Samuelsons (architect dad Phil; mom Sibyl, a fourth-grade teacher; three kids) when the eldest son, Ellis, moves into a hippie commune in the Santa Cruz Mountains. A rotating close third-person perspective spotlights each member. Fans of Jami Attenberg, Ann Patchett, and Anne Tyler need to try Huneven’s work pronto.

Sleep by Honor Jones: A breathtaking character study of a woman raising young daughters and facing memories of childhood abuse. Margaret’s 1990s New Jersey upbringing seems idyllic, but upper-middle-class suburbia conceals the perils of a dysfunctional family headed by a narcissistic, controlling mother. Jones crafts unforgettable, crystalline scenes. There are subtle echoes throughout as the past threatens to repeat. Reminiscent of Sarah Moss and Evie Wyld, and astonishing for its psychological acuity, this promises great things from Jones.

Sleep by Honor Jones: A breathtaking character study of a woman raising young daughters and facing memories of childhood abuse. Margaret’s 1990s New Jersey upbringing seems idyllic, but upper-middle-class suburbia conceals the perils of a dysfunctional family headed by a narcissistic, controlling mother. Jones crafts unforgettable, crystalline scenes. There are subtle echoes throughout as the past threatens to repeat. Reminiscent of Sarah Moss and Evie Wyld, and astonishing for its psychological acuity, this promises great things from Jones.

The Silver Book by Olivia Laing: Steeped in the homosexual demimonde of 1970s Italian cinema (Fellini and Pasolini films), with a clear antifascist message filtered through the coming-of-age story of a young Englishman trying to outrun his past. This offers the best of both worlds: the verisimilitude of true crime reportage and the intimacy of the close third person. Laing leavens the tone with some darkly comedic moments. Elegant and psychologically astute work from one of the most valuable cultural commentators out there.

The Silver Book by Olivia Laing: Steeped in the homosexual demimonde of 1970s Italian cinema (Fellini and Pasolini films), with a clear antifascist message filtered through the coming-of-age story of a young Englishman trying to outrun his past. This offers the best of both worlds: the verisimilitude of true crime reportage and the intimacy of the close third person. Laing leavens the tone with some darkly comedic moments. Elegant and psychologically astute work from one of the most valuable cultural commentators out there.

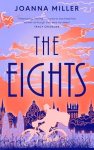

The Eights by Joanna Miller: Highly readable, book club-suitable fiction that is a sort of cross between In Memoriam and A Single Thread in terms of its subject matter: the first women to attend Oxford in the 1920s, the suffrage movement, and the plight of spare women after WWI. Different aspects are illuminated by the four central friends and their milieu. This debut has a good sense of place and reasonably strong characters. Despite some difficult subject matter, it remains resolutely jolly.

The Eights by Joanna Miller: Highly readable, book club-suitable fiction that is a sort of cross between In Memoriam and A Single Thread in terms of its subject matter: the first women to attend Oxford in the 1920s, the suffrage movement, and the plight of spare women after WWI. Different aspects are illuminated by the four central friends and their milieu. This debut has a good sense of place and reasonably strong characters. Despite some difficult subject matter, it remains resolutely jolly.

Endling by Maria Reva: What is worth doing, or writing about, in a time of war? That is the central question here, yet Reva brings considerable lightness to a novel also concerned with environmental devastation and existential loneliness. Yeva, a snail researcher in Ukraine, is contemplating suicide when Nastia and Sol rope her into a plot to kidnap 12 bride-seeking Western bachelors. The faux endings and re-dos are faltering attempts to find meaning when everything is breaking down. Both great fun to read and profound on many matters.

Endling by Maria Reva: What is worth doing, or writing about, in a time of war? That is the central question here, yet Reva brings considerable lightness to a novel also concerned with environmental devastation and existential loneliness. Yeva, a snail researcher in Ukraine, is contemplating suicide when Nastia and Sol rope her into a plot to kidnap 12 bride-seeking Western bachelors. The faux endings and re-dos are faltering attempts to find meaning when everything is breaking down. Both great fun to read and profound on many matters.

Show Don’t Tell by Curtis Sittenfeld: Sittenfeld’s second collection features characters negotiating principles and privilege in midlife. Split equally between first- and third-person perspectives, the 12 contemporary storylines spotlight everyday marital and parenting challenges. Dual timelines offer opportunities for hindsight on the events of decades ago. Nostalgic yet clear-eyed, these witty stories exploring how decisions determine the future are perfect for fans of Rebecca Makkai, Kiley Reid, and Emma Straub.

Show Don’t Tell by Curtis Sittenfeld: Sittenfeld’s second collection features characters negotiating principles and privilege in midlife. Split equally between first- and third-person perspectives, the 12 contemporary storylines spotlight everyday marital and parenting challenges. Dual timelines offer opportunities for hindsight on the events of decades ago. Nostalgic yet clear-eyed, these witty stories exploring how decisions determine the future are perfect for fans of Rebecca Makkai, Kiley Reid, and Emma Straub.

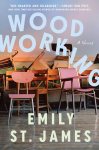

Woodworking by Emily St. James: When 35-year-old English teacher Erica realizes that not only is there another trans woman in her small South Dakota town but that it’s one of her students, she lights up. Abigail may be half her age but is further along in her transition journey and has sassy confidence. But this foul-mouthed mentor has problems of her own, starting with parents who refuse to refer to her by her chosen name. This was pure page-turning enjoyment with an important message, reminiscent of Celia Laskey and Tom Perrotta.

Woodworking by Emily St. James: When 35-year-old English teacher Erica realizes that not only is there another trans woman in her small South Dakota town but that it’s one of her students, she lights up. Abigail may be half her age but is further along in her transition journey and has sassy confidence. But this foul-mouthed mentor has problems of her own, starting with parents who refuse to refer to her by her chosen name. This was pure page-turning enjoyment with an important message, reminiscent of Celia Laskey and Tom Perrotta.

Flesh by David Szalay: Szalay explores modes of masculinity and channels, by turns, Hemingway; Fitzgerald and St. Aubyn; Hardy and McEwan. Unprocessed trauma plays out in Istvan’s life as violence against himself and others as he moves between England and Hungary and sabotages many of his relationships. He comes to know every sphere from prison to the army to the jet set. The flat affect and sparse style make this incredibly readable: a book for our times and all times and thus a worthy Booker Prize winner.

Flesh by David Szalay: Szalay explores modes of masculinity and channels, by turns, Hemingway; Fitzgerald and St. Aubyn; Hardy and McEwan. Unprocessed trauma plays out in Istvan’s life as violence against himself and others as he moves between England and Hungary and sabotages many of his relationships. He comes to know every sphere from prison to the army to the jet set. The flat affect and sparse style make this incredibly readable: a book for our times and all times and thus a worthy Booker Prize winner.

Nonfiction

The Edge of Silence: In Search of the Disappearing Sounds of Nature by Neil Ansell: I owe this a full review. I’ve read all five of Ansell’s books and consider him one of the UK’s top nature writers. Here he draws lovely parallels between his advancing hearing loss and the biodiversity crisis we face because of climate breakdown. The world is going silent for him, but rare species may well become silenced altogether. His defiant, low-carbon adventures on the fringes offer one last chance to hear some of the UK’s beloved species, mostly seabirds.

The Edge of Silence: In Search of the Disappearing Sounds of Nature by Neil Ansell: I owe this a full review. I’ve read all five of Ansell’s books and consider him one of the UK’s top nature writers. Here he draws lovely parallels between his advancing hearing loss and the biodiversity crisis we face because of climate breakdown. The world is going silent for him, but rare species may well become silenced altogether. His defiant, low-carbon adventures on the fringes offer one last chance to hear some of the UK’s beloved species, mostly seabirds.

The Quiet Ear: An Investigation of Missing Sound by Raymond Antrobus: (Another memoir about being hard of hearing!) Antrobus’s first work of nonfiction takes up the themes of his poetry – being deaf and mixed-race, losing his father, becoming a parent – and threads them into an outstanding memoir that integrates his disability and celebrates his role models. This frank, fluid memoir of finding one’s way as a poet illuminates the literal and metaphorical meanings of sound. It offers an invaluable window onto intersectional challenges.

The Quiet Ear: An Investigation of Missing Sound by Raymond Antrobus: (Another memoir about being hard of hearing!) Antrobus’s first work of nonfiction takes up the themes of his poetry – being deaf and mixed-race, losing his father, becoming a parent – and threads them into an outstanding memoir that integrates his disability and celebrates his role models. This frank, fluid memoir of finding one’s way as a poet illuminates the literal and metaphorical meanings of sound. It offers an invaluable window onto intersectional challenges.

Bigger: Essays by Ren Cedar Fuller: Fuller’s perceptive debut work offers nine linked autobiographical essays in which she seeks to see herself and family members more clearly by acknowledging disability (her Sjögren’s syndrome), neurodivergence (she theorizes that her late father was on the autism spectrum), and gender diversity (her child, Indigo, came out as transgender and nonbinary; and she realizes that three other family members are gender-nonconforming). This openhearted memoir models how to explore one’s family history.

Bigger: Essays by Ren Cedar Fuller: Fuller’s perceptive debut work offers nine linked autobiographical essays in which she seeks to see herself and family members more clearly by acknowledging disability (her Sjögren’s syndrome), neurodivergence (she theorizes that her late father was on the autism spectrum), and gender diversity (her child, Indigo, came out as transgender and nonbinary; and she realizes that three other family members are gender-nonconforming). This openhearted memoir models how to explore one’s family history.

Life on a Little-Known Planet: Dispatches from a Changing World by Elizabeth Kolbert: These exceptional essays encourage appreciation of natural wonders and technological advances but also raise the alarm over unfolding climate disasters. There are travelogues and profiles, too. Most pieces were published in The New Yorker, whose generous article length allows for robust blends of research, on-the-ground experience, interviews, and in-depth discussion of controversial issues. (Review pending for the Times Literary Supplement.)

Life on a Little-Known Planet: Dispatches from a Changing World by Elizabeth Kolbert: These exceptional essays encourage appreciation of natural wonders and technological advances but also raise the alarm over unfolding climate disasters. There are travelogues and profiles, too. Most pieces were published in The New Yorker, whose generous article length allows for robust blends of research, on-the-ground experience, interviews, and in-depth discussion of controversial issues. (Review pending for the Times Literary Supplement.)

Joyride by Susan Orlean: Another one I need to review in the new year. As a long-time staff writer for The New Yorker (like Kolbert!), Orlean has had the good fortune to be able to follow her curiosity wherever it leads, chasing the subjects that interest her and drawing readers in with her infectious enthusiasm. She gives behind-the-scenes information on lots of her early stories and on each of her books. The Orchid Thief and the movie not-exactly-based on it, Adaptation, are among my favourites, so the long section on them was a thrill for me.

Joyride by Susan Orlean: Another one I need to review in the new year. As a long-time staff writer for The New Yorker (like Kolbert!), Orlean has had the good fortune to be able to follow her curiosity wherever it leads, chasing the subjects that interest her and drawing readers in with her infectious enthusiasm. She gives behind-the-scenes information on lots of her early stories and on each of her books. The Orchid Thief and the movie not-exactly-based on it, Adaptation, are among my favourites, so the long section on them was a thrill for me.

What Sheep Think About the Weather: How to Listen to What Animals Are Trying to Say by Amelia Thomas: A comprehensive yet conversational book that effortlessly illuminates the possibilities of human–animal communication. Rooted on her Nova Scotia farm but ranging widely through research, travel, and interviews, Thomas learned all she could from scientists, trainers, and animal communicators. Full of fascinating facts wittily conveyed, this elucidates science and nurtures empathy. (I interviewed the author, too.)

What Sheep Think About the Weather: How to Listen to What Animals Are Trying to Say by Amelia Thomas: A comprehensive yet conversational book that effortlessly illuminates the possibilities of human–animal communication. Rooted on her Nova Scotia farm but ranging widely through research, travel, and interviews, Thomas learned all she could from scientists, trainers, and animal communicators. Full of fascinating facts wittily conveyed, this elucidates science and nurtures empathy. (I interviewed the author, too.)

Poetry

Common Disaster by M. Cynthia Cheung: Cheung is both a physician and a poet. Her debut collection is a lucid reckoning with everything that could and does go wrong, globally and individually. Intimate, often firsthand knowledge of human tragedies infuses the verse with melancholy honesty. Scientific vocabulary abounds here, with history providing perspective on current events. Ghazals with repeating end words reinforce the themes. These remarkable poems gild adversity with compassion and model vigilance during uncertainty.

Common Disaster by M. Cynthia Cheung: Cheung is both a physician and a poet. Her debut collection is a lucid reckoning with everything that could and does go wrong, globally and individually. Intimate, often firsthand knowledge of human tragedies infuses the verse with melancholy honesty. Scientific vocabulary abounds here, with history providing perspective on current events. Ghazals with repeating end words reinforce the themes. These remarkable poems gild adversity with compassion and model vigilance during uncertainty.

Novellas in November Wrap-Up, with Mini-Reviews

Novellas in November was a great success, helping me to finish more books in one month than I possibly ever have before. David Szalay’s Turbulence – a linked short story collection of tantalizing novella length – just arrived yesterday; I’ve started it but will be finishing it in December. The slim volume Fox 8 by George Saunders is also waiting for me at the library and I should be able to read it soon.

Novellas in November was a great success, helping me to finish more books in one month than I possibly ever have before. David Szalay’s Turbulence – a linked short story collection of tantalizing novella length – just arrived yesterday; I’ve started it but will be finishing it in December. The slim volume Fox 8 by George Saunders is also waiting for me at the library and I should be able to read it soon.

For this final installment I have 10 small books to feed back on: a mixture of fiction, graphic novels, nature books and memoirs.

Fiction:

West by Carys Davies (2018)

[149 pages]

A gritty piece of historical fiction about a widowed mule breeder, Cyrus Bellman, who sets out from Pennsylvania to find traces of the giant creatures whose bones he hears have been discovered in Kentucky. He leaves his 10-year-old daughter, Bess, in the care of his sister, knowing he’ll be gone at least two years and may never return. Chapters cut between Cy’s harrowing journey in the company of a Native American guide, Old Woman From A Distance, and Bess’s home life, threatened by the unwanted attentions of their ranch hand neighbor and the town librarian. I don’t usually mind dark stories, but this was so bleak that I found it pretty unpleasant. The deus ex machina ending saved it somewhat.

A gritty piece of historical fiction about a widowed mule breeder, Cyrus Bellman, who sets out from Pennsylvania to find traces of the giant creatures whose bones he hears have been discovered in Kentucky. He leaves his 10-year-old daughter, Bess, in the care of his sister, knowing he’ll be gone at least two years and may never return. Chapters cut between Cy’s harrowing journey in the company of a Native American guide, Old Woman From A Distance, and Bess’s home life, threatened by the unwanted attentions of their ranch hand neighbor and the town librarian. I don’t usually mind dark stories, but this was so bleak that I found it pretty unpleasant. The deus ex machina ending saved it somewhat.

Like a Mule Bringing Ice Cream to the Sun by Sarah Ladipo Manyika (2016)

[118 pages]

Morayo Da Silva is an unlikely heroine: soon to turn 75, she’s a former English professor from Nigeria who hopped between countries with her ambassador husband but now lives alone in San Francisco. The first-person narration switches around to give the perspectives of peripheral figures like a shopkeeper, a homeless woman, and Sunshine, the young friend who helps Morayo get her affairs in order after she has a fall and goes into a care home temporarily. These shifts in point of view can be abrupt, even mid-chapter, and are a little confusing. However, Morayo is a wonderful character, inspiring in her determination to live flamboyantly. I also sympathized with her love of books. I would happily have read twice as many pages about her adventures.

Morayo Da Silva is an unlikely heroine: soon to turn 75, she’s a former English professor from Nigeria who hopped between countries with her ambassador husband but now lives alone in San Francisco. The first-person narration switches around to give the perspectives of peripheral figures like a shopkeeper, a homeless woman, and Sunshine, the young friend who helps Morayo get her affairs in order after she has a fall and goes into a care home temporarily. These shifts in point of view can be abrupt, even mid-chapter, and are a little confusing. However, Morayo is a wonderful character, inspiring in her determination to live flamboyantly. I also sympathized with her love of books. I would happily have read twice as many pages about her adventures.

Graphic Novels:

Cassandra Darke by Posy Simmonds (2018)

[94 pages]

Simmonds would be great for graphic novel newbies: she writes proper, full-length stories, often loosely based on a classic plot, with lots of narration and dialogue alongside the pictures. Cassandra Darke is a 71-year-old art dealer who’s laid low by fraud allegations and then blindsided by a case of mistaken identity that brings her into contact with a couple of criminal rings. To start with she’s a Scrooge-like curmudgeon who doesn’t understand the big fuss about Christmas, but she gradually grows compassionate, especially after her own brief brush with poverty. Luckily, Simmonds doesn’t overdo the Christmas Carol comparisons. Much of the book is in appropriately somber colors, with occasional brightness, including the yellow endpapers and built-in bookmark.

Simmonds would be great for graphic novel newbies: she writes proper, full-length stories, often loosely based on a classic plot, with lots of narration and dialogue alongside the pictures. Cassandra Darke is a 71-year-old art dealer who’s laid low by fraud allegations and then blindsided by a case of mistaken identity that brings her into contact with a couple of criminal rings. To start with she’s a Scrooge-like curmudgeon who doesn’t understand the big fuss about Christmas, but she gradually grows compassionate, especially after her own brief brush with poverty. Luckily, Simmonds doesn’t overdo the Christmas Carol comparisons. Much of the book is in appropriately somber colors, with occasional brightness, including the yellow endpapers and built-in bookmark.

The Dave Walker Guide to the Church by Dave Walker (2006)

[88 pages]

Most of these comics originally appeared in the Church Times, the official newspaper of the Church of England. No doubt you’ll get the most out of it if you’re familiar with Anglican churches or the like (Episcopalian or even Roman Catholic). My mother-in-law is a C of E vicar and we’ve attended a High Anglican church for the last two years, so I got many a good snort out of the book. Walker pokes fun at bureaucracy, silly traditions, closed-mindedness, and the oddities of church buildings and parishioners’ habits. My favorite spreads compare choirs and music groups on criteria like “ability to process in” and liken different church members to chess pieces to explain church politics.

Most of these comics originally appeared in the Church Times, the official newspaper of the Church of England. No doubt you’ll get the most out of it if you’re familiar with Anglican churches or the like (Episcopalian or even Roman Catholic). My mother-in-law is a C of E vicar and we’ve attended a High Anglican church for the last two years, so I got many a good snort out of the book. Walker pokes fun at bureaucracy, silly traditions, closed-mindedness, and the oddities of church buildings and parishioners’ habits. My favorite spreads compare choirs and music groups on criteria like “ability to process in” and liken different church members to chess pieces to explain church politics.

Nature Books:

Rain: Four Walks in English Weather by Melissa Harrison (2016)

[100 pages]

In the course of a year Harrison took four rainy walks, in different seasons and different parts of England. She intersperses her observations with facts and legends about the rain, quotes from historical weather guides and poems. It has the occasional nice line, but is overall an understated nature/travel book. A noteworthy moment is when she remembers scattering her mother’s ashes on a Dartmoor tor. I most liked the argument that it’s important to not just go out in good weather, but to adapt to nature in all its moods: “I can choose now to overcome the impulse for comfort and convenience that insulates us not only from the bad in life but from much of the good. I think we need the weather, in all its forms, to feel fully human.”

In the course of a year Harrison took four rainy walks, in different seasons and different parts of England. She intersperses her observations with facts and legends about the rain, quotes from historical weather guides and poems. It has the occasional nice line, but is overall an understated nature/travel book. A noteworthy moment is when she remembers scattering her mother’s ashes on a Dartmoor tor. I most liked the argument that it’s important to not just go out in good weather, but to adapt to nature in all its moods: “I can choose now to overcome the impulse for comfort and convenience that insulates us not only from the bad in life but from much of the good. I think we need the weather, in all its forms, to feel fully human.”

The Beauties of a Cottage Garden by Gertrude Jekyll (2009)

[88 pages]

This mini-volume from Penguin’s English Journeys series feels like a bit of a cheat because it’s extracted from Wood and Garden (1899). Oh well. In short chapters Jekyll praises the variety of colors, smells and designs you’ll find in the average country garden, no matter how modest its size. She speaks of gardening as a lifelong learning process, humbly acknowledging that she’s no expert. “I hold that the best purpose of a garden is to give delight and to give refreshment of mind, to soothe, to refine, and to lift up the heart in a spirit of praise and thankfulness. … a garden is a grand teacher. It teaches patience and careful watchfulness; it teaches industry and thrift; above all, it teaches entire trust.”

This mini-volume from Penguin’s English Journeys series feels like a bit of a cheat because it’s extracted from Wood and Garden (1899). Oh well. In short chapters Jekyll praises the variety of colors, smells and designs you’ll find in the average country garden, no matter how modest its size. She speaks of gardening as a lifelong learning process, humbly acknowledging that she’s no expert. “I hold that the best purpose of a garden is to give delight and to give refreshment of mind, to soothe, to refine, and to lift up the heart in a spirit of praise and thankfulness. … a garden is a grand teacher. It teaches patience and careful watchfulness; it teaches industry and thrift; above all, it teaches entire trust.”

The Glorious Life of the Oak by John Lewis-Stempel (2018)

[87 pages]

I didn’t enjoy this as much as the other Lewis-Stempel book I read this month, The Secret Life of the Owl. There’s a lot here about the role the oak has played in British history, such as in warships and cathedral roofs. Other topics are the oak’s appearance and function in different seasons, the use of acorns and oak leaves in cooking, and the myths and legends associated with the trees. I felt there was too much minimally relevant material added in to make up the page count, such as a list of Britain’s famous named oaks and long poems from the likes of John Clare and William Cowper. While Lewis-Stempel always has a piercing eye, I wonder if he shouldn’t be saving up his energies to write more substantial books.

I didn’t enjoy this as much as the other Lewis-Stempel book I read this month, The Secret Life of the Owl. There’s a lot here about the role the oak has played in British history, such as in warships and cathedral roofs. Other topics are the oak’s appearance and function in different seasons, the use of acorns and oak leaves in cooking, and the myths and legends associated with the trees. I felt there was too much minimally relevant material added in to make up the page count, such as a list of Britain’s famous named oaks and long poems from the likes of John Clare and William Cowper. While Lewis-Stempel always has a piercing eye, I wonder if he shouldn’t be saving up his energies to write more substantial books.

General Nonfiction / Memoirs:

My Year by Roald Dahl (1993)

[64 pages]

I spotted a copy in our Stamford Airbnb bedroom and read it over our two nights there. These short month-by-month essays were composed in the last year of Dahl’s life. Writing with children in mind, he remarks on what schoolkids will experience, whether a vacation or a holiday like Guy Fawkes night. But mostly he’s led by the seasons: the birds, trees and other natural phenomena he observed year after year from his home in Buckinghamshire. Dahl points out that he never lived in a city, so he chose to mark the passing of time chiefly by changes in the countryside. This is only really for diehard fans, but it’s a nice little book to have at the bedside. (Illustrated, as always, with whimsical Quentin Blake sketches.)

I spotted a copy in our Stamford Airbnb bedroom and read it over our two nights there. These short month-by-month essays were composed in the last year of Dahl’s life. Writing with children in mind, he remarks on what schoolkids will experience, whether a vacation or a holiday like Guy Fawkes night. But mostly he’s led by the seasons: the birds, trees and other natural phenomena he observed year after year from his home in Buckinghamshire. Dahl points out that he never lived in a city, so he chose to mark the passing of time chiefly by changes in the countryside. This is only really for diehard fans, but it’s a nice little book to have at the bedside. (Illustrated, as always, with whimsical Quentin Blake sketches.)

Heart Berries by Terese Marie Mailhot (2018)

[178 pages]

Mailhot was raised on a First Nation reservation on an island off of British Columbia. She is wary of equating her family with Native stereotypes, but there’s no denying that her father was a drunk and ended up murdered. After a childhood of abuse and foster homes, Mailhot committed herself to a mental hospital for PTSD, bipolar II and an eating disorder. It was there that she started writing her story. Much of the book is addressed in the second person to her partner, who helped her move past a broken marriage and the loss of her older son to his father’s custody. Though I highlighted lots of aphoristic pronouncements, I had trouble connecting with the book as a whole: the way imprecise scenes blend into each other makes it hard to find a story line in the murk of miserable circumstances. A more accurate title would have been “Indian Condition” or “Indian Sick” (both used as chapter titles).

Mailhot was raised on a First Nation reservation on an island off of British Columbia. She is wary of equating her family with Native stereotypes, but there’s no denying that her father was a drunk and ended up murdered. After a childhood of abuse and foster homes, Mailhot committed herself to a mental hospital for PTSD, bipolar II and an eating disorder. It was there that she started writing her story. Much of the book is addressed in the second person to her partner, who helped her move past a broken marriage and the loss of her older son to his father’s custody. Though I highlighted lots of aphoristic pronouncements, I had trouble connecting with the book as a whole: the way imprecise scenes blend into each other makes it hard to find a story line in the murk of miserable circumstances. A more accurate title would have been “Indian Condition” or “Indian Sick” (both used as chapter titles).

Americashire: A Field Guide to a Marriage by Jennifer Richardson (2013)

[151 pages]

A memoir by an American woman married to a Brit and adjusting to English village life was always going to appeal to me. If you approach this as a set of comic essays on the annual rituals of rich toffs (summer fairs, auctions, horse racing, a hunt ball, a cattle market, etc.), it’s enjoyable enough. It’s when Richardson tries to be more serious, discussing her husband’s depression, their uncertainty over having children, and her possible MS, that the book falters. You can tell her editors kept badgering her to give the book a hook, and decided the maybe-baby theme was strongest. But I never sensed any real wrestling with the question. Not a bad book, but it lacks a clear enough idea of what it wants to be.

A memoir by an American woman married to a Brit and adjusting to English village life was always going to appeal to me. If you approach this as a set of comic essays on the annual rituals of rich toffs (summer fairs, auctions, horse racing, a hunt ball, a cattle market, etc.), it’s enjoyable enough. It’s when Richardson tries to be more serious, discussing her husband’s depression, their uncertainty over having children, and her possible MS, that the book falters. You can tell her editors kept badgering her to give the book a hook, and decided the maybe-baby theme was strongest. But I never sensed any real wrestling with the question. Not a bad book, but it lacks a clear enough idea of what it wants to be.

Total number of novellas read this month: 26

[not reviewed: In the Space between Moments: Finding Joy and Meaning in Medicine by Pranay Sinha –  ]

]

A few that didn’t take: The Optician of Lampedusa by Emma Jane Kirby, The Mussel Feast by Birgit Vanderbeke, Sea of Ink by Richard Weihe

My overall favorite: The Gifts of the Body by Rebecca Brown

My overall favorite: The Gifts of the Body by Rebecca Brown

Runners-up: Surfacing by Margaret Atwood, How to See Nature by Paul Evans, Bodies of Water by V. H. Leslie, and Ghost Wall by Sarah Moss

The ones that got away from me:

There’s always next year!

What’s the best novella you’ve read recently? Do you like the sound of any of the ones I read?

Booker Longlist Mini Reviews

Tomorrow the Man Booker Prize shortlist will be announced. I’d already read and reviewed four of the nominees (see my quick impressions here), and in the time since the longlist announcement I’ve managed to read another three and ruled out one more. Two were terrific; another was pretty good; the last I’ll never know because it’s clear to me I won’t read it.

His Bloody Project by Graeme Macrae Burnet

What a terrific, propulsive tale Burnet has woven out of a real-life (I think) nineteenth-century Scottish murder case. The seams between fact and fiction are so subtle you might forget you’re reading a novel, but it’s clear the author has taken great care in assembling his “documents”: witness testimonies, medical reports, a psychologist’s assessment, trial records, and – the heart of the book and the most fascinating section – a memoir written by the murderer himself. As you’re reading it you believe Roddy implicitly and feel deeply for his humiliation (the meeting with the factor and the rejection by Flora are especially agonizing scenes), but as soon as you move on to the more ‘objective’ pieces you question how he depicted things. I went back and read parts of his account two or three times, wondering how his memories squared with the facts of the case. A great one for fans of Alias Grace, though I liked this much better. This is my favorite from the Booker longlist so far.

What a terrific, propulsive tale Burnet has woven out of a real-life (I think) nineteenth-century Scottish murder case. The seams between fact and fiction are so subtle you might forget you’re reading a novel, but it’s clear the author has taken great care in assembling his “documents”: witness testimonies, medical reports, a psychologist’s assessment, trial records, and – the heart of the book and the most fascinating section – a memoir written by the murderer himself. As you’re reading it you believe Roddy implicitly and feel deeply for his humiliation (the meeting with the factor and the rejection by Flora are especially agonizing scenes), but as soon as you move on to the more ‘objective’ pieces you question how he depicted things. I went back and read parts of his account two or three times, wondering how his memories squared with the facts of the case. A great one for fans of Alias Grace, though I liked this much better. This is my favorite from the Booker longlist so far.

Eileen by Ottessa Moshfegh

“I often felt there was something wired weird in my brain, a problem so complicated only a lobotomy could solve it—I’d need a whole new mind or a whole new life.” This isn’t so much a book to enjoy as one to endure. Being in Eileen’s mind is profoundly unsettling. She’s simultaneously fascinated and disgusted by bodies; she longs for her alcoholic father’s approval even as she wonders whether she could get away with killing him. They live a life apart in their rundown home in X-ville, New England, and Eileen can’t wait to get out by whatever means necessary. When Rebecca St. John joins the staff of the boys’ prison where Eileen works, she hopes this alluring woman will be her ticket out of town.

“I often felt there was something wired weird in my brain, a problem so complicated only a lobotomy could solve it—I’d need a whole new mind or a whole new life.” This isn’t so much a book to enjoy as one to endure. Being in Eileen’s mind is profoundly unsettling. She’s simultaneously fascinated and disgusted by bodies; she longs for her alcoholic father’s approval even as she wonders whether she could get away with killing him. They live a life apart in their rundown home in X-ville, New England, and Eileen can’t wait to get out by whatever means necessary. When Rebecca St. John joins the staff of the boys’ prison where Eileen works, she hopes this alluring woman will be her ticket out of town.

There’s a creepy Hitchcock flavor to parts of the novel (I imagined Eileen played by Patricia Hitchcock as in Strangers on a Train, with Rebecca as Gene Tierney in Laura), and a nice late twist – but Moshfegh sure makes you wait for it. In the meantime you have to put up with the tedium and squalor of Eileen’s daily life, and there’s no escape from her mind. This is one of those rare novels I would have preferred to be in the third person: it would allow the reader to come to his/her own conclusions about Eileen’s psychology, and would have created more suspense because Eileen’s hindsight wouldn’t result in such heavy foreshadowing. I expected suspense but actually found this fairly slow and somewhat short of gripping.

Hot Milk by Deborah Levy

This is a most unusual mother–daughter story, set on the southern coast of Spain. Twenty-five-year-old Sofia Papastergiadis has put off her anthropology PhD to accompany her mother, Rose, on a sort of pilgrimage to Dr. Gómez’s clinic to assess what’s wrong with Rose’s legs. What I loved about this novel is the uncertainty about who each character really is. Is Rose an invalid or a first-class hypochondriac? Is Dr. Gómez a miracle worker or a quack who’s fleeced them out of 25,000 euros? As a narrator, Sofia pretends to objective anthropological observation but is just as confused by her actions as we are: she seems to deliberately court jellyfish stings, is simultaneously jealous and contemptuous of her Greek father’s young second wife, and sleeps with both Juan and Ingrid.

This is a most unusual mother–daughter story, set on the southern coast of Spain. Twenty-five-year-old Sofia Papastergiadis has put off her anthropology PhD to accompany her mother, Rose, on a sort of pilgrimage to Dr. Gómez’s clinic to assess what’s wrong with Rose’s legs. What I loved about this novel is the uncertainty about who each character really is. Is Rose an invalid or a first-class hypochondriac? Is Dr. Gómez a miracle worker or a quack who’s fleeced them out of 25,000 euros? As a narrator, Sofia pretends to objective anthropological observation but is just as confused by her actions as we are: she seems to deliberately court jellyfish stings, is simultaneously jealous and contemptuous of her Greek father’s young second wife, and sleeps with both Juan and Ingrid.

Levy imbues the novel’s relationships with psychological and mythological significance, especially the Medusa story. I don’t think the ending quite fits the tone, but overall this is a quick and worthwhile read. At the same time, it’s such an odd story that it will keep you thinking about the characters. A great entry I’d be happy to see make the shortlist.

[One I won’t be reading: The Schooldays of Jesus by J.M. Coetzee. I opened up the prequel, The Childhood of Jesus, and could only manage the first chapter. I quickly skimmed the rest but found it unutterably dull. It would take me a lot of secondary source reading to try to understand what was going on here allegorically, and it’s not made me look forward to trying more from Coetzee.]

As for the rest: I have All That Man Is by David Szalay and Serious Sweet by A.L. Kennedy on my Kindle and will probably read them whether or not they’re shortlisted. The same goes for Do Not Say We Have Nothing by Madeleine Thien, for which I’m third in a library hold queue. I’d still like to get hold of The Many by Wyl Menmuir. That leaves just Hystopia by David Means, which I can’t say I have much interest in.

As for the rest: I have All That Man Is by David Szalay and Serious Sweet by A.L. Kennedy on my Kindle and will probably read them whether or not they’re shortlisted. The same goes for Do Not Say We Have Nothing by Madeleine Thien, for which I’m third in a library hold queue. I’d still like to get hold of The Many by Wyl Menmuir. That leaves just Hystopia by David Means, which I can’t say I have much interest in.

I rarely feel like I have enough of a base of experience to make accurate predictions, but if I had to guess which six books would make it through tomorrow, I would pick:

His Bloody Project by Graeme Macrae Burnet

The Schooldays of Jesus by J.M. Coetzee

Hot Milk by Deborah Levy

The North Water by Ian McGuire

My Name Is Lucy Barton by Elizabeth Strout

Do Not Say We Have Nothing by Madeleine Thien

That would be three men and three women, and a pretty good mix of countries and genres. I’d be happy with that list.

Someone becomes addicted to benzodiazepines in The Pass by Katriona Chapman and All the World Can Hold by Jung Yun (both 2026 releases).

Someone becomes addicted to benzodiazepines in The Pass by Katriona Chapman and All the World Can Hold by Jung Yun (both 2026 releases).

A sexual encounter between two men is presaged by them relieving themselves side by side at urinals in A Room Above a Shop by Anthony Shapland and The End of Mr Y by Scarlett Thomas.

A sexual encounter between two men is presaged by them relieving themselves side by side at urinals in A Room Above a Shop by Anthony Shapland and The End of Mr Y by Scarlett Thomas.

#1 One of the books I read ‘in preparation’ for attending that conference was Small World by David Lodge, a comedic novel about professors on the international conference circuit. I’ve included it as one of the

#1 One of the books I read ‘in preparation’ for attending that conference was Small World by David Lodge, a comedic novel about professors on the international conference circuit. I’ve included it as one of the  #2 Flights and “small world” connections also fill the linked short story collection

#2 Flights and “small world” connections also fill the linked short story collection  #3 If you can bear to remember the turbulence of recent history,

#3 If you can bear to remember the turbulence of recent history,  #4 That punning title reminded me of

#4 That punning title reminded me of

Naomi Alderman, musing on the intestines, draws metaphorical connections between food, sex and death, and gives thanks that digestion and excretion are involuntary processes we don’t have to give any thought. Ned Beauman reports on misconceptions about the appendix as he frets about the odds of his bursting while he’s in America without health insurance. The late Philip Kerr describes the checkered history of the lobotomy, which used to reduce patients to a vegetative state but can now quite effectively treat epilepsy.

Naomi Alderman, musing on the intestines, draws metaphorical connections between food, sex and death, and gives thanks that digestion and excretion are involuntary processes we don’t have to give any thought. Ned Beauman reports on misconceptions about the appendix as he frets about the odds of his bursting while he’s in America without health insurance. The late Philip Kerr describes the checkered history of the lobotomy, which used to reduce patients to a vegetative state but can now quite effectively treat epilepsy. Most authors chose a particular organ because of its importance to their own health. Christina Patterson’s acne was so bad she went to the UK’s top skin specialist for PUVA light treatments, Mark Ravenhill had his gallbladder removed in an emergency surgery, and Daljit Nagra’s asthma led his parents to engage Sikh faith healers for his lungs. Two of my favorite chapters were by William Fiennes, whose extreme Crohn’s disease caused him to have a colostomy bag for two years in his early twenties, and poet Kayo Chingonyi, who has always been ashamed to admit that his parents both died of complications of HIV in Zambia. Such personal connections add poignancy to what could have been information dumps.

Most authors chose a particular organ because of its importance to their own health. Christina Patterson’s acne was so bad she went to the UK’s top skin specialist for PUVA light treatments, Mark Ravenhill had his gallbladder removed in an emergency surgery, and Daljit Nagra’s asthma led his parents to engage Sikh faith healers for his lungs. Two of my favorite chapters were by William Fiennes, whose extreme Crohn’s disease caused him to have a colostomy bag for two years in his early twenties, and poet Kayo Chingonyi, who has always been ashamed to admit that his parents both died of complications of HIV in Zambia. Such personal connections add poignancy to what could have been information dumps. During the weeks that I spent with these essays I was frequently reminded of Jan Morris’s

During the weeks that I spent with these essays I was frequently reminded of Jan Morris’s  As he ushers readers around the world, Szalay invites us to marvel at how quickly life changes and how – improbable as it may seem – we can have a real impact on people we may only meet once. There’s a strong contrast between impersonal and intimate spaces: airplane cabins and hotel rooms versus the private places where relationships start or end. The title applies to the characters’ tumultuous lives as much as to the flight conditions. They experience illness, infidelity, domestic violence, homophobia and more, but they don’t stay mired in their situations; there’s always a sense of motion and possibility, that things will change one way or another.

As he ushers readers around the world, Szalay invites us to marvel at how quickly life changes and how – improbable as it may seem – we can have a real impact on people we may only meet once. There’s a strong contrast between impersonal and intimate spaces: airplane cabins and hotel rooms versus the private places where relationships start or end. The title applies to the characters’ tumultuous lives as much as to the flight conditions. They experience illness, infidelity, domestic violence, homophobia and more, but they don’t stay mired in their situations; there’s always a sense of motion and possibility, that things will change one way or another. In a riff on the Ages of Man, Szalay gives nine vignettes of men trying to figure out what life is all about. His antiheroes range from age 17 to 73. Each section has several chapters and follows a similar pattern: a man from one European country travels to another European country; there are lots of scenes set at airports or otherwise in transit, and part of the overall atmosphere of dislocation is simply the effort of having to adjust to foreignness. These trips are made for various reasons: feckless French twentysomething Bérnard has been fired by his uncle so goes ahead with a vacation to Cyprus; tabloid journalist Kristian flies from Denmark to Spain to confirm rumors of a government minister’s involvement in a scandal; recently impoverished oligarch Aleksandr takes his yacht for a farewell Adriatic cruise.

In a riff on the Ages of Man, Szalay gives nine vignettes of men trying to figure out what life is all about. His antiheroes range from age 17 to 73. Each section has several chapters and follows a similar pattern: a man from one European country travels to another European country; there are lots of scenes set at airports or otherwise in transit, and part of the overall atmosphere of dislocation is simply the effort of having to adjust to foreignness. These trips are made for various reasons: feckless French twentysomething Bérnard has been fired by his uncle so goes ahead with a vacation to Cyprus; tabloid journalist Kristian flies from Denmark to Spain to confirm rumors of a government minister’s involvement in a scandal; recently impoverished oligarch Aleksandr takes his yacht for a farewell Adriatic cruise.

“Music and stories, even in times like these, were a refuge, a passport, everywhere.” A sweeping epic of life in China in the turbulent 1960s–80s, this is the Canadian novelist’s fourth book. Narrated from the present day by Marie (or Ma-Li), who lives in Vancouver with her mother, the novel plunges into layers of flashbacks about her family’s connection to Ai-Ming and her musician father, Sparrow. With loyalty to the Communist Party (the title is a line from its anthem) considered the gold standard of behavior and Western music widely denounced as revolutionary, these characters are in a bind: will they pursue their identity as artists, or keep their heads down to avoid trouble? This theme reminded me of Julian Barnes’s fictionalized biography of the Russian composer Shostakovich,

“Music and stories, even in times like these, were a refuge, a passport, everywhere.” A sweeping epic of life in China in the turbulent 1960s–80s, this is the Canadian novelist’s fourth book. Narrated from the present day by Marie (or Ma-Li), who lives in Vancouver with her mother, the novel plunges into layers of flashbacks about her family’s connection to Ai-Ming and her musician father, Sparrow. With loyalty to the Communist Party (the title is a line from its anthem) considered the gold standard of behavior and Western music widely denounced as revolutionary, these characters are in a bind: will they pursue their identity as artists, or keep their heads down to avoid trouble? This theme reminded me of Julian Barnes’s fictionalized biography of the Russian composer Shostakovich,

A short work of muted horror, all about atmosphere and the unexplained. Set in a Cornish fishing village, it sees newcomer Timothy Buchannan trying to figure out what happened to Perran, the man who occupied his rundown cottage until his death 10 years ago, and why everyone refuses to talk about him. Flashbacks in italics give glimpses into Timothy’s life with his wife, Lauren, who is meant to join him when he finishes the renovations; and into the fisherman Ethan’s past. I enjoyed the unsettling mood and the language used to describe the setting and Timothy’s dreams. Ultimately I’m not sure I fully understood the book, especially whether the late turns of the plot are to be viewed literally or allegorically. What I take away from it, and this is perhaps too simplistic, is an assertion that we are all joined in our losses. A quick, creepy read – you could do worse than pick it up this Halloween.

A short work of muted horror, all about atmosphere and the unexplained. Set in a Cornish fishing village, it sees newcomer Timothy Buchannan trying to figure out what happened to Perran, the man who occupied his rundown cottage until his death 10 years ago, and why everyone refuses to talk about him. Flashbacks in italics give glimpses into Timothy’s life with his wife, Lauren, who is meant to join him when he finishes the renovations; and into the fisherman Ethan’s past. I enjoyed the unsettling mood and the language used to describe the setting and Timothy’s dreams. Ultimately I’m not sure I fully understood the book, especially whether the late turns of the plot are to be viewed literally or allegorically. What I take away from it, and this is perhaps too simplistic, is an assertion that we are all joined in our losses. A quick, creepy read – you could do worse than pick it up this Halloween.

This collects 45 super-short stories that stand out for their structure, voice, and character development—all in spite of often extreme brevity. Humor and pathos provide sharp pivot points. It helps to have an unusual perspective, like that of a Venus flytrap observing a household’s upheavals (Janey Skinner’s “Carnivores”), or of potential names gathering around a baptismal font (Alberto Chimal’s “The Waterfall”). Hard as it is to choose from such a diverse bunch, I do have three favorites: Elizabeth Morton’s “Parting,” in which a divorce causes things to be literally divided; Mary-Jane Holmes’s “Trifle,” where alliteration and culinary vocabulary contrast an English summer with Middle Eastern traces; and Amir Adam’s “The Physics of Satellites,” which uses images from astronomy and a recent suicide to contrast falling, flying, and barely holding on. There are fewer highlights than in

This collects 45 super-short stories that stand out for their structure, voice, and character development—all in spite of often extreme brevity. Humor and pathos provide sharp pivot points. It helps to have an unusual perspective, like that of a Venus flytrap observing a household’s upheavals (Janey Skinner’s “Carnivores”), or of potential names gathering around a baptismal font (Alberto Chimal’s “The Waterfall”). Hard as it is to choose from such a diverse bunch, I do have three favorites: Elizabeth Morton’s “Parting,” in which a divorce causes things to be literally divided; Mary-Jane Holmes’s “Trifle,” where alliteration and culinary vocabulary contrast an English summer with Middle Eastern traces; and Amir Adam’s “The Physics of Satellites,” which uses images from astronomy and a recent suicide to contrast falling, flying, and barely holding on. There are fewer highlights than in  These nine stories examine what characters do in extreme, often violent situations. My three favorites were “Bunny,” reminiscent of The Fattest Man in Britain with its picture of a friendship between an obese man and a young woman who sees more in him than his size; “The Woodpecker and the Wolf,” a brilliantly suspenseful tale set in space – it reminded me of the Sandra Bullock movie Gravity; and “The Weir,” which imagines the unexpectedly lasting relationship between a lonely middle-aged man and the young woman he rescues from a near-suicide by drowning. “Wodwo” starts off as a terrific Christmas horror story but goes on far too long and loses power. I would say that about several of these stories, actually: they’re that bit too long, so that you start waiting for them to be over. I prefer sudden endings that give a bit of a kick. All in all, though, two-thirds of the stories are fairly memorable, and I’d say I liked this better than any of Haddon’s three novels.

These nine stories examine what characters do in extreme, often violent situations. My three favorites were “Bunny,” reminiscent of The Fattest Man in Britain with its picture of a friendship between an obese man and a young woman who sees more in him than his size; “The Woodpecker and the Wolf,” a brilliantly suspenseful tale set in space – it reminded me of the Sandra Bullock movie Gravity; and “The Weir,” which imagines the unexpectedly lasting relationship between a lonely middle-aged man and the young woman he rescues from a near-suicide by drowning. “Wodwo” starts off as a terrific Christmas horror story but goes on far too long and loses power. I would say that about several of these stories, actually: they’re that bit too long, so that you start waiting for them to be over. I prefer sudden endings that give a bit of a kick. All in all, though, two-thirds of the stories are fairly memorable, and I’d say I liked this better than any of Haddon’s three novels.  Kleeman’s debut novel,

Kleeman’s debut novel,  On Tuesday I finished All That Man Is by David Szalay, from the Booker Prize shortlist. Whether it’s a novel or actually short stories is certainly a matter for debate! After I read Madeleine Thien’s shortlisted novel (I’ll be picking it up from the library on Friday) I’ll report back on both in advance of the prize announcement at the end of October.

On Tuesday I finished All That Man Is by David Szalay, from the Booker Prize shortlist. Whether it’s a novel or actually short stories is certainly a matter for debate! After I read Madeleine Thien’s shortlisted novel (I’ll be picking it up from the library on Friday) I’ll report back on both in advance of the prize announcement at the end of October. I’m also currently making my way through How Much the Heart Can Hold, a set of seven stories from the likes of Carys Bray and Donal Ryan on the theme of different types of love, and Petina Gappah’s forthcoming collection, Rotten Row. (Both are out in early November.)

I’m also currently making my way through How Much the Heart Can Hold, a set of seven stories from the likes of Carys Bray and Donal Ryan on the theme of different types of love, and Petina Gappah’s forthcoming collection, Rotten Row. (Both are out in early November.)

And then there’s the books I’d simply never heard of. Of these I’m most interested in His Bloody Project by Graeme Macrae Burnet, based on a true-life murder in Scotland in the 1860s, and The Many by Wyl Menmuir, a debut novella about a village newcomer.

And then there’s the books I’d simply never heard of. Of these I’m most interested in His Bloody Project by Graeme Macrae Burnet, based on a true-life murder in Scotland in the 1860s, and The Many by Wyl Menmuir, a debut novella about a village newcomer.