20 Books of Summer, 19–20: Emily St. James and Abraham Verghese

Going out on a high! My last three books for the challenge (also including Beautiful Ruins) were particularly great, just the sort of absorbing and rewarding reading that I wish I could guarantee for all of my summer selections.

Woodworking by Emily St. James (2025)

Colloquially, “woodworking” is disappearing in plain sight; doing all you can to fade into the woodwork. Erica has only just admitted her identity to herself, and over the autumn of 2016 begins telling others she’s a woman – starting with her ex-wife Constance, who is now pregnant by her fiancé, John. To everyone else, Erica is still Mr. Skyberg, a 35-year-old English teacher at Mitchell High involved in local amateur dramatics. When Erica realizes that not only is there another trans woman in her small South Dakota town but that it’s one of her students, Abigail Hawkes, she lights up. Abigail may be half her age but is further along in her transition journey and has sassy confidence. But this foul-mouthed new mentor has problems of her own, starting with parents who refuse to refer to her by her chosen name. Abigail lives with her adult sister instead, and gains an unexpected surrogate family via her boyfriend Caleb, a Korean adoptee whose mother, Brooke Daniels, is directing Our Town. Brooke is surprisingly supportive given that she attends Isaiah Rose’s megachurch.

As Trump/Pence signs proliferate, a local election is heating up, too: Pastor Rose is running for State Congress on the Republican ticket, opposed by Helen Swee. Erica befriends Helen and becomes faculty advisor for the school’s Democrat club (which has all of two members: Abigail and her Leslie Knope-like friend Megan). The plot swings naturally between the personal and political, emphasizing how the personal business of 1% of the population has been made into a political football. Chapters alternate between Abigail in first person and Erica in third. The characters feel utterly real and the dialogue is as genuine as the narrative voices. The support group Erica and Abigail attend presents a range of trans experiences based on when one came of age. Some are still deep undercover. There’s a big reveal I couldn’t quite accept, though I can see its purpose. It’s particularly effective how St. James lets second- and third-person narration shade into first as characters accept their selves. Grey rectangles cover up deadnames all but once, making the point that even allies can get it wrong.

This was pure page-turning enjoyment with an important message to convey. It reminded me a lot of Under the Rainbow by Celia Laskey but also had the flavour of classic Tom Perrotta (Election). In the Author’s Note, St. James writes, “They say the single greatest determinant of whether someone will support and affirm trans people is if they know a trans person.” I feel lucky to count three trans people among my friends. It’s impossible to make detached pronouncements about bathrooms and slippery slopes if you care about people whose rights and very existence are being undermined. We should all be reading books by and about trans women. (New purchase from Bookshop.org) ![]()

The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese (2023)

All too often, I shy away from doorstoppers because they seem like too much of a time commitment. Why read 715 pages in one novel when I could read 3.5 of 200 pages each? Yet there’s something special about being lost in the middle of a great big book and trusting that wherever the story goes will be worthwhile. I let this review copy languish on the shelf for over TWO YEARS when I should have known that the author of the amazing Cutting for Stone couldn’t possibly let me down. Verghese’s second novel is very much in the same vein: a family saga that spans decades and in every generation focuses on medical issues. Verghese is a practicing doctor as well as a Stanford professor and you can tell he glories in the details of hand and brain surgeries, disability and rare diseases – and luckily, so do I.

Wider events play out in the background (wars, partition, the fall of the caste system), but the focus is always on one family in Kerala, starting in 1900 when a 12-year-old girl is brought to the Parambil estate for her arranged marriage to a 40-year-old widower. One day she will be Big Ammachi, the matriarch of a family with a mysterious Condition: In every generation, someone drowns. As a result, they all avoid water, even if it requires going hours out of their way. Her son Philipose longs to be a scholar, but is so hard of hearing that his formal education is cut short. He becomes a columnist in a local newspaper and marries Elsie, a spirited artist. Their daughter, Mariamma, trains as a doctor. In parallel, we follow the story of Digby Kilgour, a Glaswegian surgeon whose career takes him to India. Through Digby and Mariamma’s interactions with colleagues, we watch colonial incompetence and sexism play out. Addiction and suicide recur across the years. Destiny and choice lock horns. I enjoyed the window onto the small community of St. Thomas Christians and felt fond of all the characters, including Damodaran the elephant. It’s also really clever how Verghese makes the Condition a cross between a mystical curse and a diagnosable ailment. An intellectual soap opera that makes you think about storytelling, purpose and inheritance, this is extraordinary. ![]()

With thanks to Atlantic Books for the proof copy for review.

I read 10 of the books I selected in my initial planning post. I’m pleased that I picked off a couple of long-neglected review copies and several recent purchases. The rest were substituted at whim. There were two duds, but the overall quality was high, with 10 books I rated 4 stars or higher! Along with the above and Beautiful Ruins, Pet Sematary and Storm Pegs were overall highlights. I also managed to complete a row on the Bingo card, a fun add-on. And, bonus: I cleared 7 books from my shelves by reselling or giving them away after I read them.

20 Books of Summer, 5: Crudo by Olivia Laing (2018)

Behind on the challenge, as ever, I picked up a novella. It vaguely fits with a food theme as crudo, “raw” in Italian, can refer to fish or meat platters (depicted on the original hardback cover). In this context, though, it connotes the raw material of a life: a messy matrix of choices and random happenings, rooted in a particular moment in time.

This is set over four and a bit months of 2017 and steeped in the protagonist’s detached horror at political and environmental breakdown. She’s just turned 40 and, in between two trips to New York City, has a vacation in Tuscany, dabbles in writing and art criticism, and settles into married life in London even though she’s used to independence and nomadism.

This is set over four and a bit months of 2017 and steeped in the protagonist’s detached horror at political and environmental breakdown. She’s just turned 40 and, in between two trips to New York City, has a vacation in Tuscany, dabbles in writing and art criticism, and settles into married life in London even though she’s used to independence and nomadism.

For as hyper-real as the contents are, Laing is doing something experimental, even fantastical – blending biography with autofiction and cultural commentary by making her main character, apparently, Kathy Acker. Never mind that Acker died of breast cancer in 1997.

I knew nothing of Acker but – while this is clearly born of deep admiration, as well as familiarity with her every written word – that didn’t matter. Acker quotes and Trump tweets are inserted verbatim, with the sources given in a “Something Borrowed” section at the end.

Like Jenny Offill’s Weather, this is a wry and all too relatable take on current events and the average person’s hypocrisy and sense of helplessness, with the lack of speech marks and shortage of punctuation I’ve come to expect from ultramodern novels:

she might as well continue with her small and cultivated life, pick the dahlias, stake the ones that had fallen down, she’d always known whatever it was wasn’t going to last for long.

40, not a bad run in the history of human existence but she’d really rather it all kept going, water in the taps, whales in the oceans, fruits and duvets, the whole sumptuous parade

This is how it is then, walking backwards into disaster, braying all the way.

I’ve somehow read almost all of Laing’s oeuvre (barring her essays, Funny Weather) and have found books like The Trip to Echo Spring, The Lonely City and Everybody wide-ranging and insightful. Crudo feels as faithful to life as Rachel Cusk’s autofiction or Deborah Levy’s autobiography, but also like an attempt to make something altogether new out of the stuff of our unprecedented times. No doubt some of the intertextuality of this, her only fiction to date, was lost on me, but I enjoyed it much more than I expected to – it’s funny as well as eminently quotable – and that’s always a win. (Little Free Library)

I’ve somehow read almost all of Laing’s oeuvre (barring her essays, Funny Weather) and have found books like The Trip to Echo Spring, The Lonely City and Everybody wide-ranging and insightful. Crudo feels as faithful to life as Rachel Cusk’s autofiction or Deborah Levy’s autobiography, but also like an attempt to make something altogether new out of the stuff of our unprecedented times. No doubt some of the intertextuality of this, her only fiction to date, was lost on me, but I enjoyed it much more than I expected to – it’s funny as well as eminently quotable – and that’s always a win. (Little Free Library)

Rathbones Folio Prize Fiction Shortlist: Sheila Heti and Elizabeth Strout

I’ve enjoyed engaging with this year’s Rathbones Folio Prize shortlists, reading the entire poetry shortlist and two each from the nonfiction and fiction lists. These two I accessed from the library. Both Sheila Heti and Elizabeth Strout featured in the 5×15 event I attended on Tuesday evening, so in the reviews below I’ll weave in some insights from that.

Pure Colour by Sheila Heti

Sheila Heti is a divisive author; I’m sure there are those who detest her indulgent autofiction, though I’ve loved it (How Should a Person Be? and especially Motherhood). But this is another thing entirely: Heti puts two fingers up to the whole notion of rounded characterization or coherent plot. This is the thinnest of fables, fascinating for its ideas and certainly resonant for me what with the themes of losing a parent and searching for purpose in life on an earth that seems doomed to destruction … but is it a novel?

Sheila Heti is a divisive author; I’m sure there are those who detest her indulgent autofiction, though I’ve loved it (How Should a Person Be? and especially Motherhood). But this is another thing entirely: Heti puts two fingers up to the whole notion of rounded characterization or coherent plot. This is the thinnest of fables, fascinating for its ideas and certainly resonant for me what with the themes of losing a parent and searching for purpose in life on an earth that seems doomed to destruction … but is it a novel?

My summary for Bookmarks magazine gives an idea of the ridiculous plot:

Heti imagines that the life we live now—for Mira, studying at the American Academy of American Critics, working in a lamp store, grieving her father, and falling in love with Annie—is just God’s first draft. In this creation myth of sorts, everyone is born a “bear” (lover), “bird” (achiever), or “fish” (follower). Mira has a mystical experience in which she and her dead father meet as souls in a leaf, where they converse about the nature of time and how art helps us face the inevitability of death. If everything that exists will soon be wiped out, what matters?

The three-creature classification is cute enough, but a copout because it means Heti doesn’t have to spend time developing Mira (a bird), Annie (a fish), or Mira’s father (a bear), except through surreal philosophical dialogues that may or may not take place whilst she is disembodied in a leaf. It’s also uncomfortable how Heti uses sexual language for Mira’s communion with her dead dad: “she knew that the universe had ejaculated his spirit into her”.

Heti explained that the book came to her in discrete chunks, from what felt like a more intuitive place than the others, which were more of an intellectual struggle, and that she drew on her own experience of grief over her father’s death, though she had been writing it for a year beforehand.

Indeed, she appears to be tapping into primordial stories, the stuff of Greek myth or Jewish kabbalah. She writes sometimes of “God” and sometimes of “the gods”: the former regretting this first draft of things and planning how to make things better for himself the second time around; the latter out to strip humans of what they care about: “our parents, our ambitions, our friendships, our beauty—different things from different people. They strip some people more and others less. They strip us of whatever they need to in order to see us more clearly.” Appropriately, then, we follow Mira all the way through to her end, when, stripped of everything but love, she rediscovers the two major human connections of her life.

Given Ali Smith’s love of the experimental, it’s no surprise that she as a judge shortlisted this. If you’re of a philosophical bent, don’t mind negligible/non-existent plot in your novels and aren’t turned off by literary pretension, you should be fine. If you are new to Heti or unsure about trying her, though, this is probably not the right place to start. See my Goodreads review for some sample quotes, good and bad.

Lucy by the Sea by Elizabeth Strout

This was by far the best of the three Amgash books I’ve read. I think it must be the first time that Strout has set a book not in the past or at some undated near-contemporary moment but in the actual world with its current events, which inevitably means it gets political. I had my doubts about how successful she’d be with such hyper-realism, but this really worked.

As Covid hits, William whisks Lucy away from her New York City apartment to a house at the coast in Crosby, Maine. She’s an Everywoman recounting the fear and confusion of those early pandemic days, hearing of friends and relatives falling ill and knowing there’s nothing she can do about it. Isolation, mostly imposed on her but partially chosen – she finally gets a writing studio, the first ‘room of her own’ she’s ever had – gives her time to ponder the trauma of her childhood and what went wrong in her marriage to William. She worries for her two adult daughters but, for the first time, you get the sense that the strength and wisdom she’s earned through bitter experience will help her support them in making good choices.

As Covid hits, William whisks Lucy away from her New York City apartment to a house at the coast in Crosby, Maine. She’s an Everywoman recounting the fear and confusion of those early pandemic days, hearing of friends and relatives falling ill and knowing there’s nothing she can do about it. Isolation, mostly imposed on her but partially chosen – she finally gets a writing studio, the first ‘room of her own’ she’s ever had – gives her time to ponder the trauma of her childhood and what went wrong in her marriage to William. She worries for her two adult daughters but, for the first time, you get the sense that the strength and wisdom she’s earned through bitter experience will help her support them in making good choices.

Here in rural Maine, Lucy sees similar deprivation to what she grew up with in Illinois and also meets real people – nice, friendly people – who voted for Trump and refuse to be vaccinated. I loved how Strout shows us Lucy observing and then, through a short story, compassionately imagining herself into the situation of conservative cops and drug addicts. “Try to go outside your comfort level, because that’s where interesting things will happen on the page,” is her philosophy. This felt like real insight into a writer’s inspirations.

Another neat thing Strout does here, as she has done before, is to stitch her oeuvre together by including references to most of her other books. So she becomes friends with Bob Burgess, volunteers alongside Olive Kitteridge’s nursing home caregiver (and I expect their rental house is supposed to be the one Olive vacated), and meets the pastor’s daughter from Abide with Me. My only misgiving is that she recounts Bob Burgess’s whole story, replete with spoilers, such that I don’t feel I need to read The Burgess Boys.

Lucy has emotional intelligence (“You’re not stupid about the human heart,” Bob Burgess tells her) and real, hard-won insight into herself (“My childhood had been a lockdown”). Readers as well as writers have really taken this character to heart, admiring her seemingly effortless voice. Strout said she does not think of this as a ‘pandemic novel’ because she’s always most interested in character. She believes the most important thing is the sound of the sentences and that a writer has to determine the shape of the material from the inside. She was very keen to separate herself from Lucy, and in fact came across as rather terse. I had somehow expected her to have a higher voice, to be warmer and softer. (“Ah, you’re not Lucy, you’re Olive!” I thought to myself.)

Predictions

This year’s judges are Guy Gunaratne, Jackie Kay and Ali Smith. Last year’s winner was a white man, so I’m going to say in 2023 the prize should go to a woman of colour, and in fact I wouldn’t be surprised if all three category winners were women of colour. My own taste in the shortlists is, perhaps unsurprisingly, very white-lady-ish and non-experimental. But I think Amy Bloom and Elizabeth Strout’s books are too straightforward and Fiona Benson’s not edgy enough. So I’m expecting:

Fiction: Scary Monsters by Michelle de Kretser

Nonfiction: Constructing a Nervous System by Margo Jefferson

Poetry: Quiet by Victoria Adukwei Bulley (or Cane, Corn & Gully by Safiya Kamaria Kinshasa)

Overall winner: Constructing a Nervous System by Margo Jefferson (or Quiet by Victoria Adukwei Bulley)

This is my 1,200th blog post!

Recent BookBrowse & Shiny New Books Reviews, and Book Club Ado

Excerpts from and links to some of my recent online writing for other places:

BookBrowse

Three O’Clock in the Morning by Gianrico Carofiglio

The quotation that gives Carofiglio’s tender novel its title is from F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Crack-Up: “In a real dark night of the soul it is always three o’clock in the morning.” It lends an appropriate sense of time suspended, of earnest seeking and extreme circumstances: The main action of the book takes place over just a few days in June of 1983, when Italian teenager Antonio and his father are stranded in Marseilles while there for Antonio to be seen by an epilepsy specialist. The gift of this time outside of time allows them to get to know each other better, such that the memory of the trip will be precious to Antonio even decades later. I appreciated how the limited setting heightened this short novel’s emotions. Carofiglio invites readers to peer between the leisurely progression of events to see the bond that is being formed. (See my full review at BookBrowse. See also my related article on HarperVia, a new publishing imprint for international literature.)

The quotation that gives Carofiglio’s tender novel its title is from F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Crack-Up: “In a real dark night of the soul it is always three o’clock in the morning.” It lends an appropriate sense of time suspended, of earnest seeking and extreme circumstances: The main action of the book takes place over just a few days in June of 1983, when Italian teenager Antonio and his father are stranded in Marseilles while there for Antonio to be seen by an epilepsy specialist. The gift of this time outside of time allows them to get to know each other better, such that the memory of the trip will be precious to Antonio even decades later. I appreciated how the limited setting heightened this short novel’s emotions. Carofiglio invites readers to peer between the leisurely progression of events to see the bond that is being formed. (See my full review at BookBrowse. See also my related article on HarperVia, a new publishing imprint for international literature.)

The Dictionary of Lost Words by Pip Williams

Inspired by the composition of the Oxford English Dictionary, this Australian debut novel explores the lives of the women on its fringes through the words that were omitted. The suffrage movement and World War I loom large as the storyline enters the 1910s. I most appreciated the relationships Esme has with the various women in her life. The main action spans the 40 years of the original composition of the OED. That scope means there is a lot of skipping forward in time. Especially in the first half, I longed for the narrative to slow down so I could spend more time with this character. Despite the first-person narration, I never felt I knew Esme very well. Women’s bonds and women’s words are strong themes in this forthrightly feminist novel that, despite its flaws, would make a great book club selection. (See my full review at BookBrowse. See also my reading list of books about dictionaries and lost words.)

Inspired by the composition of the Oxford English Dictionary, this Australian debut novel explores the lives of the women on its fringes through the words that were omitted. The suffrage movement and World War I loom large as the storyline enters the 1910s. I most appreciated the relationships Esme has with the various women in her life. The main action spans the 40 years of the original composition of the OED. That scope means there is a lot of skipping forward in time. Especially in the first half, I longed for the narrative to slow down so I could spend more time with this character. Despite the first-person narration, I never felt I knew Esme very well. Women’s bonds and women’s words are strong themes in this forthrightly feminist novel that, despite its flaws, would make a great book club selection. (See my full review at BookBrowse. See also my reading list of books about dictionaries and lost words.)

Shiny New Books

Notes from Deep Time: The Hidden Stories of the Earth Beneath Our Feet by Helen Gordon

To assess the place of humanity, we can look back to prehistory, but also forward to envision the “deep future.” (It was only in a late chapter on nuclear waste disposal sites and warning messages to the future that I found too much direct overlap with Footprints by David Farrier.) This engagingly blends both tactics, surveying the fields of geology and palaeontology and pondering the future traces of the Anthropocene. I most enjoyed the middle chapters, in which science meets wildlife and cultural studies. For instance, a chapter on ammonites leads into a profile of Mary Anning and the history of both fossil hunting and women in STEM careers. The prose is well pitched to the layman’s level. Interviews, travels, and snapshots from her own life generally keep the material from becoming too dry. An invigorating interdisciplinary tour. (See my full review at Shiny New Books.)

To assess the place of humanity, we can look back to prehistory, but also forward to envision the “deep future.” (It was only in a late chapter on nuclear waste disposal sites and warning messages to the future that I found too much direct overlap with Footprints by David Farrier.) This engagingly blends both tactics, surveying the fields of geology and palaeontology and pondering the future traces of the Anthropocene. I most enjoyed the middle chapters, in which science meets wildlife and cultural studies. For instance, a chapter on ammonites leads into a profile of Mary Anning and the history of both fossil hunting and women in STEM careers. The prose is well pitched to the layman’s level. Interviews, travels, and snapshots from her own life generally keep the material from becoming too dry. An invigorating interdisciplinary tour. (See my full review at Shiny New Books.)

My book club has been meeting via Zoom since April 2020. This is a common state of affairs for book clubs around the world. Especially since we have 12 members (if everyone attends, which is rare), we haven’t been able to contemplate meeting in person as of yet. However, a subset of us meet midway between the monthly reads to discuss women’s classics like Marge Piercy’s Woman on the Edge of Time. For next week’s meeting on Mrs. Dalloway, we are going to attempt a six-person get-together in one member’s house.

Anyway, a neat thing we did last month was a Zoom chat with the author: a BBC correspondent who happens to be the brother of one of our members. If you’re a news junkie in the UK, you may know the name Jon Sopel, though since I don’t have a telly or ever listen to radio, I hadn’t encountered him until this “in-person” meet-up. He has been the BBC’s North America Editor since 2014.

Anyway, a neat thing we did last month was a Zoom chat with the author: a BBC correspondent who happens to be the brother of one of our members. If you’re a news junkie in the UK, you may know the name Jon Sopel, though since I don’t have a telly or ever listen to radio, I hadn’t encountered him until this “in-person” meet-up. He has been the BBC’s North America Editor since 2014.

UnPresidented is the third book he wrote over the course of the Trump presidency. It started off as a diary of the 2020 election campaign, beginning in July 2019, but of course soon morphed into something slightly different: a chronicle of life in D.C. and London during Covid-19 and a record of the Trump mishandling of the pandemic. But as well as a farcical election process and a public health crisis, 2020’s perfect storm also included economic collapse and social upheaval – thanks to the murder of George Floyd and the subsequent Black Lives Matter protests worldwide plus isolated rioting.

UnPresidented served as a good reminder for me of the timeline of events and the full catalogue of outrages committed by Trump and his cronies. You just have to shake your head over the litany of ridiculous things he said and did, and got away with – any one of which might have sunk another president or candidate. The style is breezy and off-the-cuff, so the book reads quickly. There’s a good balance between world events and personal ones, with his family split across the UK and Australia. I appreciated the insight into differences from the British system. I thought it would be depressing reading back through the events of 2020, but for the most part the knowledge that everything turned out “right” allowed me to see the humour in it. Still, I found it excruciating reading about the four days following the election.

Sopel kindly gave us an hour of his time one Wednesday evening before he had to go on air and answered our questions about Biden, Harris, journalistic ethics, and more. He was charming and eloquent, as befits his profession.

Would any of these books interest you?

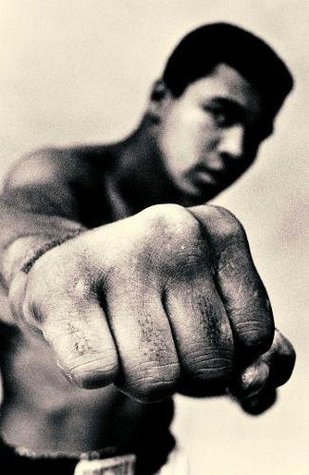

Biography of the Month: Ali: A Life by Jonathan Eig

The first book I ever reviewed on this blog, nearly three years ago, happened to be Jonathan Eig’s The Birth of the Pill. It was the strength of the writing in that offbeat work of history, as well as rave reviews for this 2017 biography of Muhammad Ali (1942–2016), that led me to pick up a sport-themed book. I’m the furthest thing from a sports fan you could imagine, but I approached this as a book about a cultural icon and read it with a spirit of curiosity about how Eig would shape this life story and separate the facts from the legend. It’s a riveting account of outliving segregation and developing a personal style and world-beating confidence; it’s a sobering tale of facing consequences and having your own body fail you. I loved it.

The first book I ever reviewed on this blog, nearly three years ago, happened to be Jonathan Eig’s The Birth of the Pill. It was the strength of the writing in that offbeat work of history, as well as rave reviews for this 2017 biography of Muhammad Ali (1942–2016), that led me to pick up a sport-themed book. I’m the furthest thing from a sports fan you could imagine, but I approached this as a book about a cultural icon and read it with a spirit of curiosity about how Eig would shape this life story and separate the facts from the legend. It’s a riveting account of outliving segregation and developing a personal style and world-beating confidence; it’s a sobering tale of facing consequences and having your own body fail you. I loved it.

Today would have been Ali’s 76th birthday, so in honor of the occasion – and his tendency to spout off-the-cuff rhymes about his competitors’ shortfalls and his own greatness – I’ve turned his life story into a book review of sorts, in rhyming couplets.

Born into 1940s Kentucky,

this fine boy had decent luck – he

surpassed his angry, cheating father

though he shared his name; no bother –

he’d not be Cassius Clay much longer.

He knew he was so much stronger

than all those other boys. Racing

the bus with Rudy; embracing

the help of a white policeman,

his first boxing coach – this guardian

prepared him for Olympic gold

(the last time Cassius did as told?).

A self-promoter from the start, he

was no scholar but won hearts; he

hogged every crowd’s full attention

but his faults are worth a mention:

he hoarded Caddys and Royces

and made bad financial choices;

he went through one, two, three, four wives

and lots of other dames besides;

his kids – no closer than his fans –

hardly even got a chance.

Cameos from bin Laden, Trump,

Toni Morrison and more: jump

ahead and you’ll see an actor,

envoy, entrepreneur, preacher,

recognized-all-round-the-world brand

(though maybe things got out of hand).

Ali was all things to all men

and fitted in the life of ten

but though he tested a lot of walks,

mostly he just wanted to box.

The fights: Frazier, Foreman, Liston –

they’re all here, and the details stun.

Eig gives a vivid blow-by-blow

such that you will feel like you know

what it’s like to be in the ring:

dodge, jab, weave; hear that left hook sing

past your ear. Catch rest at the ropes

but don’t stay too long like a dope.

If, like Ali, you sting and float,

keep an eye on your age and bloat –

the young, slim ones will catch you out.

Bow out before too many bouts.

Ignore the signs if you so choose

(ain’t got many brain cells to lose –

these blows to the head ain’t no joke);

retirement talk ain’t foolin’ folk,

can’t you give up on earning dough

and think more about your own soul?

1968 Esquire cover. By George Lois (Esquire Magazine) [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)%5D, via Wikimedia Commons.

Allah laid a call on your head:

To raise up the black man’s status

and ask white men why they hate us;

to resist the Vietnam draft

though that nearly got you the shaft

and lost you your name, your title

and (close) your rank as an idol.

Was it all real, your piety?

Was it worth it in society?

Nation of Islam was your crew

but sure did leave you in the stew

with that Vietcong kerfuffle

and Malcolm/Muhammad shuffle.

Through U.S. missions (after 9/11)

you explained it ain’t about heaven

and who you’ll kill to get you there;

it’s about peace, being God’s heir.

Is this story all about race?

Eig believes it deserves its place

as the theme of Ali’s life: he

was born in segregation, see,

a black fighter in a white world,

but stereotypes he hurled

right back in their faces: Uncle

Tom Negro? Naw, even punch-drunk he’ll

smash your categories and crush

your expectations. You can flush

that flat dismissal down the john;

don’t think you know what’s going on.

Dupe, ego, clown, greedy, hero:

larger than life, Jesus or Nero?

How to see both, that’s the kicker;

Eig avoids ‘good’ and ‘bad’ stickers

but shows a life laid bare and

how win and lose ain’t fair and

history is of our making

and half of legacy is faking

and all you got to do is spin

the world round ’till it lets you in.

Biography’s all ’bout the arc

and though this story gets real dark,

there’s a glister to it all the same.

A man exists beyond the fame.

What do you know beneath the name?

Less, I’d make a bet, than you think.

Come over here and take a drink:

this is long, deep, satisfying;

you won’t escape without crying.

Based on 600 interviews,

this fresh account is full of news

and fit for all, not just sports fans.

Whew, let’s give it up for Eig, man.

My rating:

Review: Hillbilly Elegy by J.D. Vance

“Americans call them hillbillies, rednecks, or white trash. I call them neighbors, friends, and family.”

This is one of those books I’d heard high praise about from America but never thought I’d be able to get hold of in the UK. I looked into borrowing it from the public library on my last trip to the States, but even nearly a year after its publication the reservation list was still a mile long. So I was delighted to hear that Hillbilly Elegy was being released in paperback in the UK last month. For British readers, it will provide a welcome window onto a working-class world that is easily caricatured but harder to understand in a nuanced way.

J.D. Vance knows hillbilly America from the inside but also has the necessary distance to be able to draw helpful conclusions about it: born in the “Rust Belt” of Ohio to parents who didn’t complete high school, he served in the Marine Corps in Iraq, attended Ohio State University and Yale Law School, and became a successful investor with a venture capital firm. He was one of the lucky ones who didn’t give into lower-middle-class despair and widespread vices like alcoholism and hard drugs, even though his mother was an addict and installed a “revolving door of father figures” in his life after his father abandoned them.

Vance attributes his success to the stability provided by his grandparents, his beloved Mamaw and Papaw. They were part of a large wave of migration from Kentucky to Ohio, where they moved so Papaw could work in the Armco Steel mill. Prejudice assaulted the couple from both sides: Kentucky folk thought they’d grown too big for their britches, while in Ohio they were maligned as dirty hillbillies. Mamaw, in particular, is a wonderful character so eccentric you couldn’t make her up, with her fierce love backed up by a pistol.

Vance attributes his success to the stability provided by his grandparents, his beloved Mamaw and Papaw. They were part of a large wave of migration from Kentucky to Ohio, where they moved so Papaw could work in the Armco Steel mill. Prejudice assaulted the couple from both sides: Kentucky folk thought they’d grown too big for their britches, while in Ohio they were maligned as dirty hillbillies. Mamaw, in particular, is a wonderful character so eccentric you couldn’t make her up, with her fierce love backed up by a pistol.

The book is powerful because it gives concrete, personal examples of social movements: it’s no dry history of how the Scots-Irish residents of Appalachia switched allegiance from the Democratic Party to the Republican after Richard Nixon, though Vance does fill in these broad brushstrokes, but a family memoir that situates Mamaw and Papaw’s experience, and later his own, in the context of the history of the region and the whole country.

I most appreciated the author’s determined use of the first-person plural, especially later in the book: he includes himself in the hillbilly “we” such that he’s not some newly gentrified snob denouncing welfare queens: he knows these people and this lifestyle and recognizes its contradictions; he also knows that but for the grace of God he could have slipped into the same bad habits.

Jackson [Kentucky] is undoubtedly full of the nicest people in the world; it is also full of drug addicts and at least one man who can find the time to make eight children but can’t find the time to support them. It is unquestionably beautiful, but its beauty is obscured by the environmental waste and loose trash that scatters the countryside. Its people are hardworking, except of course for the many food stamp recipients who show little interest in honest work.

At Yale Law School Vance felt out of place for the first time in his life. One of the most important things he learned from professors like Amy Chua was the value of social capital: in his new world of lawyers, senators and judges it really was all about who you know. At law firm interviews, he had no idea what cutlery to use in restaurants and had to text his girlfriend for help. For as much as he’s adapted to non-hillbilly life in the intervening years, he still notices in himself the hallmarks of a stressful, impoverished upbringing: a fight or flight approach to conflict and an honor culture that makes him prone to nurturing feuds.

Although I enjoyed it simply as a memoir, I can see this book especially appealing to people who are interested in the politics and psychology of the lower middle class (perhaps an American equivalent to Owen Jones’s Chavs, a book I never got through). British readers will, I think, be surprised to learn that Vance is on the conservative end of the spectrum and has political aspirations. Essentially, he doesn’t think the government can fix things for struggling country folk, though certain social policies might help. He seems to think it’s more a question of personal responsibility – and also that churches have a major role to play.

There is a cultural movement in the white working class to blame problems on society or the government, and that movement gains adherents by the day.

Mamaw always had two gods: Jesus Christ and the United States of America. I was no different, and neither was anyone else I knew.

(These strike me as alien ideas in the UK, apart from short-lived strategies like David Cameron’s “Big Society” – except, perhaps, if one goes all the way back to Thatcherism.)

Much has been made in the British press about this book’s ability to explain the rise of Donald Trump. This is an overstatement, and perhaps even misleading, when you consider the author’s conservatism; he never mentions Trump, and never engages in any specific political discussions. But what it is helpful for is exposing a mindset of rugged, defiant individualism that often shades into hopelessness. I have my own share of redneck relatives, and though I feel far removed from the world Vance depicts, I can see its traces in my family tree. I’m glad he had the guts to draw on his experience and write this hard-hitting book.

My rating:

Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and Culture in Crisis was first published in the UK by William Collins in September 2016. My thanks to Katherine Patrick for sending a free paperback for review.

Note: Ron Howard is to direct and produce a movie version of the book.

The Emma Press has published poetry pamphlets before, but this is their inaugural full-length work. Rachel Spence’s second collection is in two parts: first is “Call & Response,” a sonnet sequence structured as a play and considering her relationship with her mother. Act 1 starts in 1976 and zooms forward to key moments when they fell out and then reversed their estrangement. The next section finds them in the new roles of patient and carer. “Your final check-up. August. Nimbus clouds / prised open by Delft blue. Waiting is hard.” In Act 3, death is near; “in that quantum hinge, we made / an alphabet from love’s ungrammared stutter.” The poems of the last act are dated precisely, not just to a month and year as earlier but down to the very day, hour and minute. Whether in Ludlow or Venice, Spence crystallizes moments from the ongoingness of grief, drawing images from the natural world.

The Emma Press has published poetry pamphlets before, but this is their inaugural full-length work. Rachel Spence’s second collection is in two parts: first is “Call & Response,” a sonnet sequence structured as a play and considering her relationship with her mother. Act 1 starts in 1976 and zooms forward to key moments when they fell out and then reversed their estrangement. The next section finds them in the new roles of patient and carer. “Your final check-up. August. Nimbus clouds / prised open by Delft blue. Waiting is hard.” In Act 3, death is near; “in that quantum hinge, we made / an alphabet from love’s ungrammared stutter.” The poems of the last act are dated precisely, not just to a month and year as earlier but down to the very day, hour and minute. Whether in Ludlow or Venice, Spence crystallizes moments from the ongoingness of grief, drawing images from the natural world. Not only the pun-tastic title, but also the excellent nominative determinism of chef and food historian Dr Neil Buttery’s name, earned this a place in my

Not only the pun-tastic title, but also the excellent nominative determinism of chef and food historian Dr Neil Buttery’s name, earned this a place in my  Foust’s fifth collection – at 41 pages, the length of a long chapbook – is in conversation with the language and storyline of 1984. George Orwell’s classic took on new prescience for her during Donald Trump’s first presidential term, a period marked by a pandemic as well as by corruption, doublespeak and violence. “Rally

Foust’s fifth collection – at 41 pages, the length of a long chapbook – is in conversation with the language and storyline of 1984. George Orwell’s classic took on new prescience for her during Donald Trump’s first presidential term, a period marked by a pandemic as well as by corruption, doublespeak and violence. “Rally

Merritt asked about the novel’s magic realist element and how stylistically different his novels have been from each other. He was glad she found the book funny, as “life is tragicomic.” In an effort not to get stuck in a rut, he deliberately ‘breaks the mould’ after each book and starts over. This has not made him popular with his publisher!

Merritt asked about the novel’s magic realist element and how stylistically different his novels have been from each other. He was glad she found the book funny, as “life is tragicomic.” In an effort not to get stuck in a rut, he deliberately ‘breaks the mould’ after each book and starts over. This has not made him popular with his publisher!

Last year’s Dylan Thomas Prize winner interviewed this year’s winner, and it was clear that the mutual admiration was strong. Though I had mixed feelings about Luster (

Last year’s Dylan Thomas Prize winner interviewed this year’s winner, and it was clear that the mutual admiration was strong. Though I had mixed feelings about Luster (

Shipstead (also a Dylan Thomas Prize winner) echoed something Leilani had said: that she starts a novel with questions, not answers. Such humility is refreshing, and a sure way to avoid being preachy in fiction. Her new novel, Great Circle, is among my

Shipstead (also a Dylan Thomas Prize winner) echoed something Leilani had said: that she starts a novel with questions, not answers. Such humility is refreshing, and a sure way to avoid being preachy in fiction. Her new novel, Great Circle, is among my

Lockwood is the only novelist to be included on the Atlantic’s roster of best tweets. She and Nina Stibbe, who interviewed her, agreed that 1) things aren’t funny when they try too hard and 2) the Internet used to be a taboo subject for fiction – producing time-stamped references that editors used to remove. “I had so many observations and I didn’t know where to put them,” Lockwood said, and it seems to her perverse to not write about something that is such a major part of our daily lives. The title of her Women’s Prize-shortlisted novel, No One Is Talking About This (

Lockwood is the only novelist to be included on the Atlantic’s roster of best tweets. She and Nina Stibbe, who interviewed her, agreed that 1) things aren’t funny when they try too hard and 2) the Internet used to be a taboo subject for fiction – producing time-stamped references that editors used to remove. “I had so many observations and I didn’t know where to put them,” Lockwood said, and it seems to her perverse to not write about something that is such a major part of our daily lives. The title of her Women’s Prize-shortlisted novel, No One Is Talking About This (

Like Lockwood, Pachico was part of the “10 @ 10” series featuring debut novelists (though her first book, the linked story collection

Like Lockwood, Pachico was part of the “10 @ 10” series featuring debut novelists (though her first book, the linked story collection

Speaking to Arifa Akbar about

Speaking to Arifa Akbar about

I’ve read more of and gotten on better with Heti’s work than Cusk’s, so this was a rare case of being perhaps more interested in interviewer than interviewee. Heti said that, compared with the Outline trilogy, Cusk’s new novel Second Place feels wilder and more instinctual. Cusk, speaking from the Greek island of Tinos, where she is researching marble quarrying, described her book in often vague yet overall intriguing terms: it’s about exile and the illicit, she said; about femininity and entitlement to speak; about the domestic space and how things are legitimized; about the adoption of male values and the “rightness of the artist.”

I’ve read more of and gotten on better with Heti’s work than Cusk’s, so this was a rare case of being perhaps more interested in interviewer than interviewee. Heti said that, compared with the Outline trilogy, Cusk’s new novel Second Place feels wilder and more instinctual. Cusk, speaking from the Greek island of Tinos, where she is researching marble quarrying, described her book in often vague yet overall intriguing terms: it’s about exile and the illicit, she said; about femininity and entitlement to speak; about the domestic space and how things are legitimized; about the adoption of male values and the “rightness of the artist.”

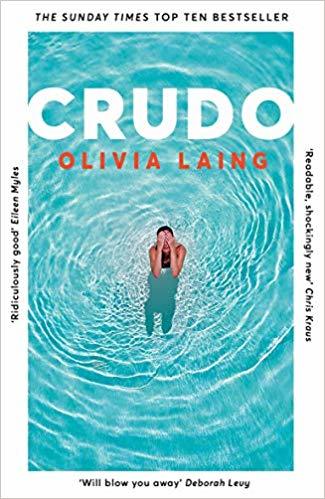

In person Kingsolver was a delight – warm and funny, with a generic American accent that doesn’t betray her Kentucky roots. In her beaded caftan and knee-high oxblood boots, she exuded girlish energy despite the shock of white in her hair. Although her fervor for the scientific method and a socially responsible government came through clearly, there was a lightness about her that tempered the weighty issues she covers in her novel.

In person Kingsolver was a delight – warm and funny, with a generic American accent that doesn’t betray her Kentucky roots. In her beaded caftan and knee-high oxblood boots, she exuded girlish energy despite the shock of white in her hair. Although her fervor for the scientific method and a socially responsible government came through clearly, there was a lightness about her that tempered the weighty issues she covers in her novel.