Reading Wales Month: Tishani Doshi & Ruth Janette Ruck (#ReadingWales25)

It’s my first time participating in Reading Wales Month, hosted this year by Karen of BookerTalk. I happened to be reading a collection by a Welsh-Gujarati poet, and added a Welsh hill farming memoir to my stack so I could review two books towards this challenge.

A God at the Door by Tishani Doshi (2021)

I discovered Doshi through the phenomenal Girls Are Coming out of the Woods, which I reviewed for Wasafiri literary magazine. This fourth collection is just as rich in long, forthright feminist and political poems. Violence against women is a theme that crops up again and again in her work, as in “Every Unbearable Thing”: “this is not / a poem against longing / but against the kind of one-way / desire that herds you into a / dead-end alley”. The arresting title of the sestina “We Will Not Kill You. We’ll Just Shoot You in the Vagina” is something the former Philippines president Rodrigo Duterte said in 2018 in reference to female communist rebels. Doshi links femicide and ecocide with “A Possible Explanation as to Why We Mutilate Women & Trees, which Tries to End on a Note of Hope”. Her poem titles are often striking and tell stories in and of themselves. Several made me laugh, such as “Advice for Pliny the Elder, Big Daddy of Mansplainers,” which is shaped like a menstrual cup.

I discovered Doshi through the phenomenal Girls Are Coming out of the Woods, which I reviewed for Wasafiri literary magazine. This fourth collection is just as rich in long, forthright feminist and political poems. Violence against women is a theme that crops up again and again in her work, as in “Every Unbearable Thing”: “this is not / a poem against longing / but against the kind of one-way / desire that herds you into a / dead-end alley”. The arresting title of the sestina “We Will Not Kill You. We’ll Just Shoot You in the Vagina” is something the former Philippines president Rodrigo Duterte said in 2018 in reference to female communist rebels. Doshi links femicide and ecocide with “A Possible Explanation as to Why We Mutilate Women & Trees, which Tries to End on a Note of Hope”. Her poem titles are often striking and tell stories in and of themselves. Several made me laugh, such as “Advice for Pliny the Elder, Big Daddy of Mansplainers,” which is shaped like a menstrual cup.

In defiance of those who would destroy it, Doshi affirms the primacy of the body. The joyfully absurd “In a Dream I Give Birth to a Sumo Wrestler” ends with the lines “How easy to forget / that all we have are these bodies. That all of this, all of this is holy.” Poems are inspired by Emily Dickinson and Frida Kahlo as well as by real events that provoke outrage. The clever folktale-like pair “Microeconomics” and “Macroeconomics” contrasts a woman dutifully growing peas and trying to get ahead with exploitative situations: “One man sits on another if he can. … One man goes / into the mines for another man to sparkle.” I also found many wise words on grief. Doshi is a treasure. (Secondhand – Green Ink Booksellers, Hay-on-Wye) ![]()

Place of Stones by Ruth Janette Ruck (1961)

“Farming is rather like the theatre—whatever happens the show must go on.”

I reviewed Ruck’s Along Came a Llama several years ago when it was re-released by Faber. This was the first of her three memoirs about life at Carneddi (which means “place of stones”), the hill farm in North Wales that she and her family took over in the 1950s. After college, Ruck trained at a farm on the Isle of Wight and later completed an apprenticeship at Oathill Farm, Oxfordshire under George Henderson, who seems to have been something of a celebrity farmer back then (he contributes a brief but complimentary foreword). By age 20 she was in full charge of Carneddi, where they kept sheep, cattle and fowl. Many of their neighbours had Welsh as a first or only language. At that time, farmers were eligible for government grants. Ruck put in an intensive hen-rearing barn and started growing strawberries and rearing turkeys for Christmas.

I reviewed Ruck’s Along Came a Llama several years ago when it was re-released by Faber. This was the first of her three memoirs about life at Carneddi (which means “place of stones”), the hill farm in North Wales that she and her family took over in the 1950s. After college, Ruck trained at a farm on the Isle of Wight and later completed an apprenticeship at Oathill Farm, Oxfordshire under George Henderson, who seems to have been something of a celebrity farmer back then (he contributes a brief but complimentary foreword). By age 20 she was in full charge of Carneddi, where they kept sheep, cattle and fowl. Many of their neighbours had Welsh as a first or only language. At that time, farmers were eligible for government grants. Ruck put in an intensive hen-rearing barn and started growing strawberries and rearing turkeys for Christmas.

Even when things were going well, it was a hand-to-mouth existence and storms or illness could set everything back. The Rucks renovated a nearby cottage to serve as a holiday let. Another windfall came in the bizarre form of a nearby film shoot by Twentieth Century Fox (The Inn of the Sixth Happiness, starring Ingrid Bergman). Mountainous North Wales stood in for China, and the film crew hired Ruck as a driver and, like many locals, as an occasional extra. This book was light and mildly entertaining, though probably more detailed about everyday farm work and projects than I needed. I was reminded again of Doreen Tovey, especially in the passage about Topsy the pet black sheep, but also this time of Betty Macdonald (The Egg and I) and Janet White (The Sheep Stell). (Secondhand – Lions bookshop, Alnwick) ![]()

Childless Voices by Lorna Gibb

People end up not having children for any number of reasons: medical issues, bereavement, a lack of finances, not having a partner at the right time, or the simple decision not to become a parent. The subtitle of Lorna Gibb’s Childless Voices acknowledges these various routes: “Stories of Longing, Loss, Resistance and Choice.”

For Gibb, a university lecturer, biographer and novelist, the childless state was involuntary, a result of severe endometriosis that led to infertility and early menopause. Although this has been a source of sadness for her and her husband, she knows that she has it easy compared to women in other parts of the world. Through her research and Skype interviews, she hears horrific stories about infertile women who meet with domestic violence and social ostracism and are sometimes driven to suicide. In Ghana childless women can be branded as witches and exiled. Meanwhile, some are never given the chance to have the children they might long for: Gibb cites China’s one-child policy, female genital mutilation, and enforced sterilization programs like those of the Roma in Yugoslavia and the Quechua in Peru.

For Gibb, a university lecturer, biographer and novelist, the childless state was involuntary, a result of severe endometriosis that led to infertility and early menopause. Although this has been a source of sadness for her and her husband, she knows that she has it easy compared to women in other parts of the world. Through her research and Skype interviews, she hears horrific stories about infertile women who meet with domestic violence and social ostracism and are sometimes driven to suicide. In Ghana childless women can be branded as witches and exiled. Meanwhile, some are never given the chance to have the children they might long for: Gibb cites China’s one-child policy, female genital mutilation, and enforced sterilization programs like those of the Roma in Yugoslavia and the Quechua in Peru.

Gibb is admirably comprehensive here, considering every possible aspect of childlessness. Particularly interesting are the different cultural adaptations childless women make. Certain countries allow polygamy, giving a second wife a chance to bear children on behalf of an infertile one; Kenya and other parts of sub-Saharan Africa recognize ‘marriages’ between childless women so they can create a family and support system. In Albania being a “sworn virgin” is an old and venerable custom. And, of course, there are any number of support groups and online communities. The situation of those who were once parents but are no longer is especially wrenching. Stillbirth only started to be talked about in the 1980s, Gibb notes, but even today is seen as a lesser loss than that of a child who dies later in life.

The author believes there is societal injustice in terms of who has access to fertility treatment and how the state deals with childless people. In the UK, she characterizes IVF as a “postcode lottery”: where you live often determines how many free cycles you’re entitled to on the NHS. In the USA, meanwhile, fertility treatment is so expensive that only those with a certain level of wealth can consider it. The childless may also feel ‘punished’ by tax breaks that favor parents and workplaces that expect non-parents to work unsociable hours. In a sense, then, the childless contribute more but benefit less.

Chosen childlessness is perhaps given short shrift at just 32 pages out of 239. However, it’s still a very thorough treatment of the reasons why couples decide not to become parents, including cultural norms, career goals, self-knowledge and environmental concerns. No surprise that this was the chapter that resonated with me the most. I also especially enjoyed the personal interludes (all titled “A Short Note on…”) in which Gibb celebrates her feminist, childless heroes like Frida Kahlo and Anaïs Nin and writes about how much becoming a godmother meant to her but also of the sadness of seeing a good friend’s teenage son die of a brain tumor.

By coincidence, I’ve recently read another book on the same topic: Do You Have Kids? Life when the Answer Is No, by Kate Kaufmann (coming out in America next month). Gibb primarily traces the many different reasons for childlessness; Kaufmann mostly addresses the question of “now what?” – how women without children approach careers, wider family life, housing options, spirituality and the notion of leaving a legacy. Gibb’s approach is international and comparative, while Kaufmann’s is largely specific to the USA. Though the two authors are childless due to endometriosis and infertility, they feel sisterhood with women who never became mothers for whatever reason. I’d say these two books are complementary rather than rivals, and reveal valuable perspectives that can sometimes be overlooked.

By coincidence, I’ve recently read another book on the same topic: Do You Have Kids? Life when the Answer Is No, by Kate Kaufmann (coming out in America next month). Gibb primarily traces the many different reasons for childlessness; Kaufmann mostly addresses the question of “now what?” – how women without children approach careers, wider family life, housing options, spirituality and the notion of leaving a legacy. Gibb’s approach is international and comparative, while Kaufmann’s is largely specific to the USA. Though the two authors are childless due to endometriosis and infertility, they feel sisterhood with women who never became mothers for whatever reason. I’d say these two books are complementary rather than rivals, and reveal valuable perspectives that can sometimes be overlooked.

My rating:

Childless Voices was published by Granta on February 7th. My thanks to the publisher for the free copy for review.

The latest in SelfMadeHero’s Art Masters series (I’ve also reviewed their books on

The latest in SelfMadeHero’s Art Masters series (I’ve also reviewed their books on

Eight of the 11 stories are in the third person and most protagonists are young or middle-aged women navigating marriage/divorce and motherhood. A driving examiner finds herself in the same situation as her teenage test-taker; a wife finds evidence of her actor husband’s adultery. In “Damascus,” Mia worries her son might be on drugs, but doesn’t question her own self-destructive habits. Inspired by Marie Kondo, Rachel tries to pare her life back to the basics in “CobRa.” In “King Midas,” Oscar learns that all is not golden with his mistress. “Sky Bar” has Fawn stuck in her hometown airport during a blizzard. I particularly liked the ridiculous situations Florida housemates get themselves into in “Pandemic Behavior,” and the second-person “Twist and Shout,” about loving an elderly father even though he’s infuriating.

Eight of the 11 stories are in the third person and most protagonists are young or middle-aged women navigating marriage/divorce and motherhood. A driving examiner finds herself in the same situation as her teenage test-taker; a wife finds evidence of her actor husband’s adultery. In “Damascus,” Mia worries her son might be on drugs, but doesn’t question her own self-destructive habits. Inspired by Marie Kondo, Rachel tries to pare her life back to the basics in “CobRa.” In “King Midas,” Oscar learns that all is not golden with his mistress. “Sky Bar” has Fawn stuck in her hometown airport during a blizzard. I particularly liked the ridiculous situations Florida housemates get themselves into in “Pandemic Behavior,” and the second-person “Twist and Shout,” about loving an elderly father even though he’s infuriating. Plain Jane getting the hot guy … that never happens, right? In fact, Sally has a theory about this very dilemma, named after her schlubby TNO office-mate: The Danny Horst Rule states that ordinary men may date and even marry actresses or supermodels, but reverse the genders and it never works. A fundamental lack of confidence means that, whenever she feels too vulnerable, Sally resorts to snarky comedy and sabotages her chances at happiness. But when, midway through the summer of 2020, she gets an out-of-the-blue e-mail from Noah, she wonders if this relationship has potential in the real world. (This, for me, is the peak: when you find out that interest is requited; that the person you’ve been thinking about for years has also been thinking about you. Whatever comes next pales in comparison to this moment.)

Plain Jane getting the hot guy … that never happens, right? In fact, Sally has a theory about this very dilemma, named after her schlubby TNO office-mate: The Danny Horst Rule states that ordinary men may date and even marry actresses or supermodels, but reverse the genders and it never works. A fundamental lack of confidence means that, whenever she feels too vulnerable, Sally resorts to snarky comedy and sabotages her chances at happiness. But when, midway through the summer of 2020, she gets an out-of-the-blue e-mail from Noah, she wonders if this relationship has potential in the real world. (This, for me, is the peak: when you find out that interest is requited; that the person you’ve been thinking about for years has also been thinking about you. Whatever comes next pales in comparison to this moment.) I reviewed

I reviewed  A reread of a book that transformed my understanding of gender back in 2006. Morris (d. 2020) was a trans pioneer. Her concise memoir opens “I was three or perhaps four years old when I realized that I had been born into the wrong body, and should really be a girl.” Sitting under the family piano, little James knew it, but it took many years – a journalist’s career, including the scoop of the first summiting of Mount Everest in 1953; marriage and five children; and nearly two decades of hormone therapy – before a sex reassignment surgery in Morocco in 1972 physically confirmed it. I was struck this time by Morris’s feeling of having been a spy in all-male circles and taking advantage of that privilege while she could. She speculates that her travel books arose from “incessant wandering as an outer expression of my inner journey.” The focus is more on her unchanging soul than on her body, so this is not a sexual tell-all. She paints hers as a spiritual quest toward true identity and there is only joy at new life rather than regret at time wasted in the ‘wrong’ one. (Public library)

A reread of a book that transformed my understanding of gender back in 2006. Morris (d. 2020) was a trans pioneer. Her concise memoir opens “I was three or perhaps four years old when I realized that I had been born into the wrong body, and should really be a girl.” Sitting under the family piano, little James knew it, but it took many years – a journalist’s career, including the scoop of the first summiting of Mount Everest in 1953; marriage and five children; and nearly two decades of hormone therapy – before a sex reassignment surgery in Morocco in 1972 physically confirmed it. I was struck this time by Morris’s feeling of having been a spy in all-male circles and taking advantage of that privilege while she could. She speculates that her travel books arose from “incessant wandering as an outer expression of my inner journey.” The focus is more on her unchanging soul than on her body, so this is not a sexual tell-all. She paints hers as a spiritual quest toward true identity and there is only joy at new life rather than regret at time wasted in the ‘wrong’ one. (Public library)

This was my third memoir by the author; I reviewed

This was my third memoir by the author; I reviewed

A woman, her partner (R), and their baby son flee a flooded London in search of a place of safety, traveling by car and boat and camping with friends and fellow refugees. “How easily we have got used to it all, as though we knew what was coming all along,” she says. Her baby, Z, tethers her to the corporeal world. What actually happens? Well, on the one hand it’s very familiar if you’ve read any dystopian fiction; on the other hand it is vague because characters only designated by initials are hard to keep straight and the text is in one- or two-sentence or -paragraph chunks punctuated by asterisks (and dull observations): “Often, I am unsure whether something is a bird or a leaf. *** Z likes to eat butter in chunks. *** We are overrun by mice.” etc. It’s touching how Z’s early milestones structure the book, but for the most part the style meant this wasn’t my cup of tea. (Secondhand purchase)

A woman, her partner (R), and their baby son flee a flooded London in search of a place of safety, traveling by car and boat and camping with friends and fellow refugees. “How easily we have got used to it all, as though we knew what was coming all along,” she says. Her baby, Z, tethers her to the corporeal world. What actually happens? Well, on the one hand it’s very familiar if you’ve read any dystopian fiction; on the other hand it is vague because characters only designated by initials are hard to keep straight and the text is in one- or two-sentence or -paragraph chunks punctuated by asterisks (and dull observations): “Often, I am unsure whether something is a bird or a leaf. *** Z likes to eat butter in chunks. *** We are overrun by mice.” etc. It’s touching how Z’s early milestones structure the book, but for the most part the style meant this wasn’t my cup of tea. (Secondhand purchase)

Pick this up right away if you loved Danielle Evans’s

Pick this up right away if you loved Danielle Evans’s

After reviewing Josipovici’s

After reviewing Josipovici’s  Otsuka’s

Otsuka’s

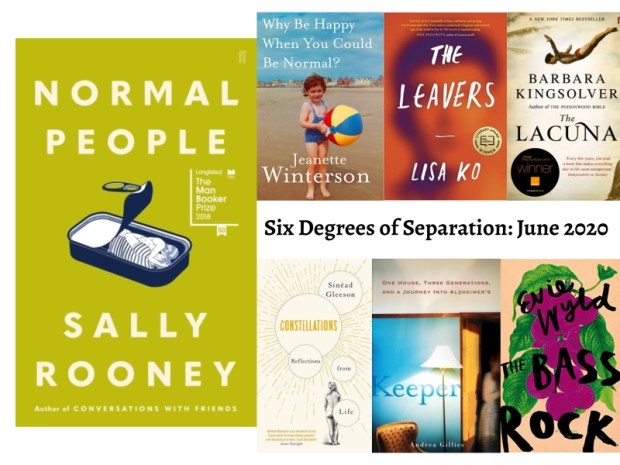

#6 Violence against women is also the theme of The Bass Rock by Evie Wyld, my novel of 2020 so far. While it ranges across the centuries, it always sticks close to the title location, an uninhabited island off the east coast of Scotland. It cycles through its three strands in an ebb and flow pattern that is appropriate to the coastal setting and creates a sense of time’s fluidity. This is not a puzzle book where everything fits together. Instead, it is a haunting echo chamber where elements keep coming back, stinging a little more each time. A must-read, especially for fans of Claire Fuller, Sarah Moss and Lucy Wood. (See my full

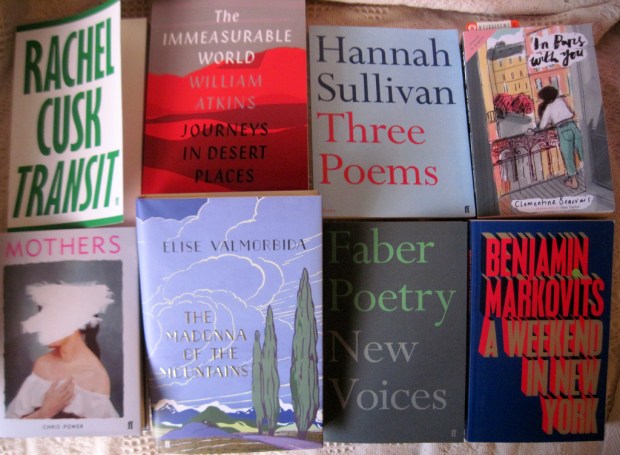

#6 Violence against women is also the theme of The Bass Rock by Evie Wyld, my novel of 2020 so far. While it ranges across the centuries, it always sticks close to the title location, an uninhabited island off the east coast of Scotland. It cycles through its three strands in an ebb and flow pattern that is appropriate to the coastal setting and creates a sense of time’s fluidity. This is not a puzzle book where everything fits together. Instead, it is a haunting echo chamber where elements keep coming back, stinging a little more each time. A must-read, especially for fans of Claire Fuller, Sarah Moss and Lucy Wood. (See my full  I’ve never been to an event quite like this. Publisher Faber & Faber, which will be celebrating its 90th birthday in 2019, previewed its major releases through to September. Most of the attendees seemed to be booksellers and publishing insiders. Drinks were on a buffet table at the back; books were on a buffet table along the side. Glass of champagne in hand, it was time to plunder the free books on offer. I ended up taking one of everything, with the exception of Rachel Cusk’s trilogy: I couldn’t make it through Outline and am not keen enough on her writing to get an advanced copy of Kudos, but figured I might give her another try with the middle book, Transit.

I’ve never been to an event quite like this. Publisher Faber & Faber, which will be celebrating its 90th birthday in 2019, previewed its major releases through to September. Most of the attendees seemed to be booksellers and publishing insiders. Drinks were on a buffet table at the back; books were on a buffet table along the side. Glass of champagne in hand, it was time to plunder the free books on offer. I ended up taking one of everything, with the exception of Rachel Cusk’s trilogy: I couldn’t make it through Outline and am not keen enough on her writing to get an advanced copy of Kudos, but figured I might give her another try with the middle book, Transit.

The two main characters Mears keeps coming back to in the course of the play are Bert Brocklesby, a Yorkshire preacher, and philosopher Bertrand Russell. Brocklesby refused to fight and, when he and other COs were shipped off to France anyway, resisted doing any work that supported the war effort, even peeling the potatoes that would be fed to soldiers. He and his fellow COs were beaten, placed in solitary confinement, and threatened with execution. Meanwhile, Russell and others in the No-Conscription Fellowship fought for their rights back in London. There’s a wonderful scene in the play where Russell, clad in nothing but a towel after a skinny dip, pleads with Prime Minister Asquith.

The two main characters Mears keeps coming back to in the course of the play are Bert Brocklesby, a Yorkshire preacher, and philosopher Bertrand Russell. Brocklesby refused to fight and, when he and other COs were shipped off to France anyway, resisted doing any work that supported the war effort, even peeling the potatoes that would be fed to soldiers. He and his fellow COs were beaten, placed in solitary confinement, and threatened with execution. Meanwhile, Russell and others in the No-Conscription Fellowship fought for their rights back in London. There’s a wonderful scene in the play where Russell, clad in nothing but a towel after a skinny dip, pleads with Prime Minister Asquith.