Best Books of 2025: The Runners-Up

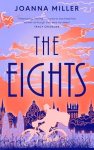

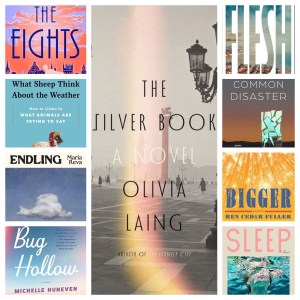

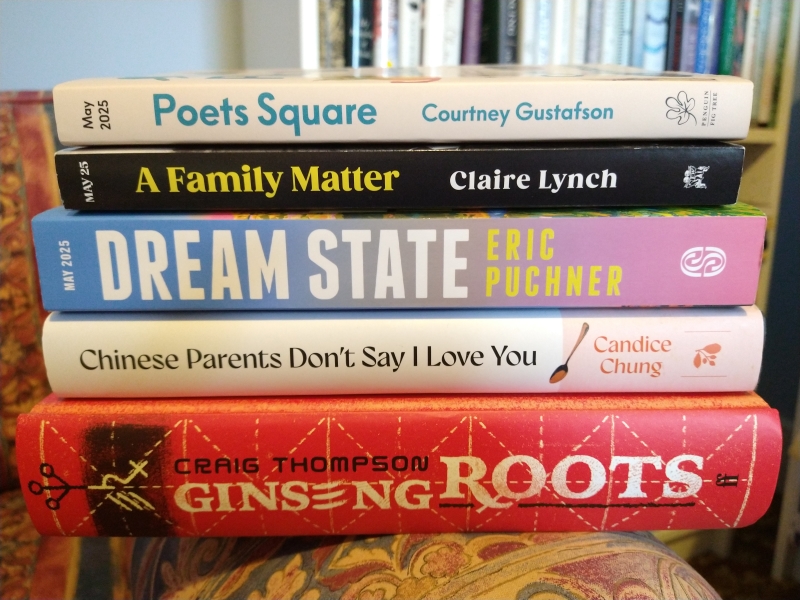

Coming up tomorrow: my list of the 15 best 2025 releases I’ve read. Here are 15 more that nearly made the cut. Pictured below are the ones I read / could get my hands on in print; the rest were e-copies or in-demand library books. Links are to my full reviews where available.

Fiction

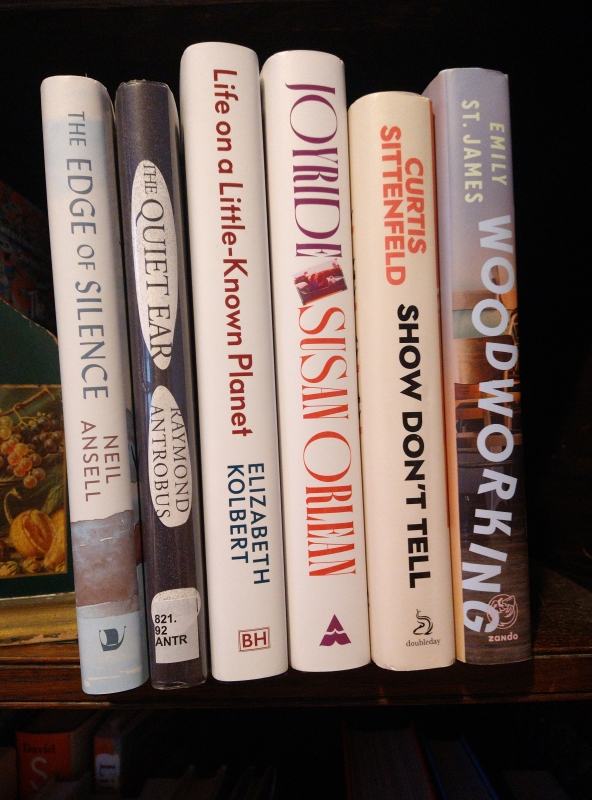

Bug Hollow by Michelle Huneven: A glistening portrait of a lovably dysfunctional California family beset by losses through the years but expanded through serendipity and friendship. Life changes forever for the Samuelsons (architect dad Phil; mom Sibyl, a fourth-grade teacher; three kids) when the eldest son, Ellis, moves into a hippie commune in the Santa Cruz Mountains. A rotating close third-person perspective spotlights each member. Fans of Jami Attenberg, Ann Patchett, and Anne Tyler need to try Huneven’s work pronto.

Bug Hollow by Michelle Huneven: A glistening portrait of a lovably dysfunctional California family beset by losses through the years but expanded through serendipity and friendship. Life changes forever for the Samuelsons (architect dad Phil; mom Sibyl, a fourth-grade teacher; three kids) when the eldest son, Ellis, moves into a hippie commune in the Santa Cruz Mountains. A rotating close third-person perspective spotlights each member. Fans of Jami Attenberg, Ann Patchett, and Anne Tyler need to try Huneven’s work pronto.

Sleep by Honor Jones: A breathtaking character study of a woman raising young daughters and facing memories of childhood abuse. Margaret’s 1990s New Jersey upbringing seems idyllic, but upper-middle-class suburbia conceals the perils of a dysfunctional family headed by a narcissistic, controlling mother. Jones crafts unforgettable, crystalline scenes. There are subtle echoes throughout as the past threatens to repeat. Reminiscent of Sarah Moss and Evie Wyld, and astonishing for its psychological acuity, this promises great things from Jones.

Sleep by Honor Jones: A breathtaking character study of a woman raising young daughters and facing memories of childhood abuse. Margaret’s 1990s New Jersey upbringing seems idyllic, but upper-middle-class suburbia conceals the perils of a dysfunctional family headed by a narcissistic, controlling mother. Jones crafts unforgettable, crystalline scenes. There are subtle echoes throughout as the past threatens to repeat. Reminiscent of Sarah Moss and Evie Wyld, and astonishing for its psychological acuity, this promises great things from Jones.

The Silver Book by Olivia Laing: Steeped in the homosexual demimonde of 1970s Italian cinema (Fellini and Pasolini films), with a clear antifascist message filtered through the coming-of-age story of a young Englishman trying to outrun his past. This offers the best of both worlds: the verisimilitude of true crime reportage and the intimacy of the close third person. Laing leavens the tone with some darkly comedic moments. Elegant and psychologically astute work from one of the most valuable cultural commentators out there.

The Silver Book by Olivia Laing: Steeped in the homosexual demimonde of 1970s Italian cinema (Fellini and Pasolini films), with a clear antifascist message filtered through the coming-of-age story of a young Englishman trying to outrun his past. This offers the best of both worlds: the verisimilitude of true crime reportage and the intimacy of the close third person. Laing leavens the tone with some darkly comedic moments. Elegant and psychologically astute work from one of the most valuable cultural commentators out there.

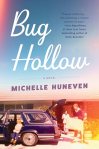

The Eights by Joanna Miller: Highly readable, book club-suitable fiction that is a sort of cross between In Memoriam and A Single Thread in terms of its subject matter: the first women to attend Oxford in the 1920s, the suffrage movement, and the plight of spare women after WWI. Different aspects are illuminated by the four central friends and their milieu. This debut has a good sense of place and reasonably strong characters. Despite some difficult subject matter, it remains resolutely jolly.

The Eights by Joanna Miller: Highly readable, book club-suitable fiction that is a sort of cross between In Memoriam and A Single Thread in terms of its subject matter: the first women to attend Oxford in the 1920s, the suffrage movement, and the plight of spare women after WWI. Different aspects are illuminated by the four central friends and their milieu. This debut has a good sense of place and reasonably strong characters. Despite some difficult subject matter, it remains resolutely jolly.

Endling by Maria Reva: What is worth doing, or writing about, in a time of war? That is the central question here, yet Reva brings considerable lightness to a novel also concerned with environmental devastation and existential loneliness. Yeva, a snail researcher in Ukraine, is contemplating suicide when Nastia and Sol rope her into a plot to kidnap 12 bride-seeking Western bachelors. The faux endings and re-dos are faltering attempts to find meaning when everything is breaking down. Both great fun to read and profound on many matters.

Endling by Maria Reva: What is worth doing, or writing about, in a time of war? That is the central question here, yet Reva brings considerable lightness to a novel also concerned with environmental devastation and existential loneliness. Yeva, a snail researcher in Ukraine, is contemplating suicide when Nastia and Sol rope her into a plot to kidnap 12 bride-seeking Western bachelors. The faux endings and re-dos are faltering attempts to find meaning when everything is breaking down. Both great fun to read and profound on many matters.

Show Don’t Tell by Curtis Sittenfeld: Sittenfeld’s second collection features characters negotiating principles and privilege in midlife. Split equally between first- and third-person perspectives, the 12 contemporary storylines spotlight everyday marital and parenting challenges. Dual timelines offer opportunities for hindsight on the events of decades ago. Nostalgic yet clear-eyed, these witty stories exploring how decisions determine the future are perfect for fans of Rebecca Makkai, Kiley Reid, and Emma Straub.

Show Don’t Tell by Curtis Sittenfeld: Sittenfeld’s second collection features characters negotiating principles and privilege in midlife. Split equally between first- and third-person perspectives, the 12 contemporary storylines spotlight everyday marital and parenting challenges. Dual timelines offer opportunities for hindsight on the events of decades ago. Nostalgic yet clear-eyed, these witty stories exploring how decisions determine the future are perfect for fans of Rebecca Makkai, Kiley Reid, and Emma Straub.

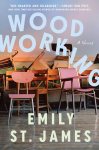

Woodworking by Emily St. James: When 35-year-old English teacher Erica realizes that not only is there another trans woman in her small South Dakota town but that it’s one of her students, she lights up. Abigail may be half her age but is further along in her transition journey and has sassy confidence. But this foul-mouthed mentor has problems of her own, starting with parents who refuse to refer to her by her chosen name. This was pure page-turning enjoyment with an important message, reminiscent of Celia Laskey and Tom Perrotta.

Woodworking by Emily St. James: When 35-year-old English teacher Erica realizes that not only is there another trans woman in her small South Dakota town but that it’s one of her students, she lights up. Abigail may be half her age but is further along in her transition journey and has sassy confidence. But this foul-mouthed mentor has problems of her own, starting with parents who refuse to refer to her by her chosen name. This was pure page-turning enjoyment with an important message, reminiscent of Celia Laskey and Tom Perrotta.

Flesh by David Szalay: Szalay explores modes of masculinity and channels, by turns, Hemingway; Fitzgerald and St. Aubyn; Hardy and McEwan. Unprocessed trauma plays out in Istvan’s life as violence against himself and others as he moves between England and Hungary and sabotages many of his relationships. He comes to know every sphere from prison to the army to the jet set. The flat affect and sparse style make this incredibly readable: a book for our times and all times and thus a worthy Booker Prize winner.

Flesh by David Szalay: Szalay explores modes of masculinity and channels, by turns, Hemingway; Fitzgerald and St. Aubyn; Hardy and McEwan. Unprocessed trauma plays out in Istvan’s life as violence against himself and others as he moves between England and Hungary and sabotages many of his relationships. He comes to know every sphere from prison to the army to the jet set. The flat affect and sparse style make this incredibly readable: a book for our times and all times and thus a worthy Booker Prize winner.

Nonfiction

The Edge of Silence: In Search of the Disappearing Sounds of Nature by Neil Ansell: I owe this a full review. I’ve read all five of Ansell’s books and consider him one of the UK’s top nature writers. Here he draws lovely parallels between his advancing hearing loss and the biodiversity crisis we face because of climate breakdown. The world is going silent for him, but rare species may well become silenced altogether. His defiant, low-carbon adventures on the fringes offer one last chance to hear some of the UK’s beloved species, mostly seabirds.

The Edge of Silence: In Search of the Disappearing Sounds of Nature by Neil Ansell: I owe this a full review. I’ve read all five of Ansell’s books and consider him one of the UK’s top nature writers. Here he draws lovely parallels between his advancing hearing loss and the biodiversity crisis we face because of climate breakdown. The world is going silent for him, but rare species may well become silenced altogether. His defiant, low-carbon adventures on the fringes offer one last chance to hear some of the UK’s beloved species, mostly seabirds.

The Quiet Ear: An Investigation of Missing Sound by Raymond Antrobus: (Another memoir about being hard of hearing!) Antrobus’s first work of nonfiction takes up the themes of his poetry – being deaf and mixed-race, losing his father, becoming a parent – and threads them into an outstanding memoir that integrates his disability and celebrates his role models. This frank, fluid memoir of finding one’s way as a poet illuminates the literal and metaphorical meanings of sound. It offers an invaluable window onto intersectional challenges.

The Quiet Ear: An Investigation of Missing Sound by Raymond Antrobus: (Another memoir about being hard of hearing!) Antrobus’s first work of nonfiction takes up the themes of his poetry – being deaf and mixed-race, losing his father, becoming a parent – and threads them into an outstanding memoir that integrates his disability and celebrates his role models. This frank, fluid memoir of finding one’s way as a poet illuminates the literal and metaphorical meanings of sound. It offers an invaluable window onto intersectional challenges.

Bigger: Essays by Ren Cedar Fuller: Fuller’s perceptive debut work offers nine linked autobiographical essays in which she seeks to see herself and family members more clearly by acknowledging disability (her Sjögren’s syndrome), neurodivergence (she theorizes that her late father was on the autism spectrum), and gender diversity (her child, Indigo, came out as transgender and nonbinary; and she realizes that three other family members are gender-nonconforming). This openhearted memoir models how to explore one’s family history.

Bigger: Essays by Ren Cedar Fuller: Fuller’s perceptive debut work offers nine linked autobiographical essays in which she seeks to see herself and family members more clearly by acknowledging disability (her Sjögren’s syndrome), neurodivergence (she theorizes that her late father was on the autism spectrum), and gender diversity (her child, Indigo, came out as transgender and nonbinary; and she realizes that three other family members are gender-nonconforming). This openhearted memoir models how to explore one’s family history.

Life on a Little-Known Planet: Dispatches from a Changing World by Elizabeth Kolbert: These exceptional essays encourage appreciation of natural wonders and technological advances but also raise the alarm over unfolding climate disasters. There are travelogues and profiles, too. Most pieces were published in The New Yorker, whose generous article length allows for robust blends of research, on-the-ground experience, interviews, and in-depth discussion of controversial issues. (Review pending for the Times Literary Supplement.)

Life on a Little-Known Planet: Dispatches from a Changing World by Elizabeth Kolbert: These exceptional essays encourage appreciation of natural wonders and technological advances but also raise the alarm over unfolding climate disasters. There are travelogues and profiles, too. Most pieces were published in The New Yorker, whose generous article length allows for robust blends of research, on-the-ground experience, interviews, and in-depth discussion of controversial issues. (Review pending for the Times Literary Supplement.)

Joyride by Susan Orlean: Another one I need to review in the new year. As a long-time staff writer for The New Yorker (like Kolbert!), Orlean has had the good fortune to be able to follow her curiosity wherever it leads, chasing the subjects that interest her and drawing readers in with her infectious enthusiasm. She gives behind-the-scenes information on lots of her early stories and on each of her books. The Orchid Thief and the movie not-exactly-based on it, Adaptation, are among my favourites, so the long section on them was a thrill for me.

Joyride by Susan Orlean: Another one I need to review in the new year. As a long-time staff writer for The New Yorker (like Kolbert!), Orlean has had the good fortune to be able to follow her curiosity wherever it leads, chasing the subjects that interest her and drawing readers in with her infectious enthusiasm. She gives behind-the-scenes information on lots of her early stories and on each of her books. The Orchid Thief and the movie not-exactly-based on it, Adaptation, are among my favourites, so the long section on them was a thrill for me.

What Sheep Think About the Weather: How to Listen to What Animals Are Trying to Say by Amelia Thomas: A comprehensive yet conversational book that effortlessly illuminates the possibilities of human–animal communication. Rooted on her Nova Scotia farm but ranging widely through research, travel, and interviews, Thomas learned all she could from scientists, trainers, and animal communicators. Full of fascinating facts wittily conveyed, this elucidates science and nurtures empathy. (I interviewed the author, too.)

What Sheep Think About the Weather: How to Listen to What Animals Are Trying to Say by Amelia Thomas: A comprehensive yet conversational book that effortlessly illuminates the possibilities of human–animal communication. Rooted on her Nova Scotia farm but ranging widely through research, travel, and interviews, Thomas learned all she could from scientists, trainers, and animal communicators. Full of fascinating facts wittily conveyed, this elucidates science and nurtures empathy. (I interviewed the author, too.)

Poetry

Common Disaster by M. Cynthia Cheung: Cheung is both a physician and a poet. Her debut collection is a lucid reckoning with everything that could and does go wrong, globally and individually. Intimate, often firsthand knowledge of human tragedies infuses the verse with melancholy honesty. Scientific vocabulary abounds here, with history providing perspective on current events. Ghazals with repeating end words reinforce the themes. These remarkable poems gild adversity with compassion and model vigilance during uncertainty.

Common Disaster by M. Cynthia Cheung: Cheung is both a physician and a poet. Her debut collection is a lucid reckoning with everything that could and does go wrong, globally and individually. Intimate, often firsthand knowledge of human tragedies infuses the verse with melancholy honesty. Scientific vocabulary abounds here, with history providing perspective on current events. Ghazals with repeating end words reinforce the themes. These remarkable poems gild adversity with compassion and model vigilance during uncertainty.

Book Serendipity, Mid-April to Mid-June

I call it “Book Serendipity” when two or more books that I read at the same time or in quick succession have something in common – the more bizarre, the better. This is a regular feature of mine every couple of months. Because I usually have 20–30 books on the go at once, I suppose I’m more prone to such incidents. People frequently ask how I remember all of these coincidences. The answer is: I jot them down on scraps of paper or input them immediately into a file on my PC desktop; otherwise, they would flit away!

The following are in roughly chronological order.

- Raising a wild animal but (mostly) calling it by its species rather than by a pet name (so “Pigeon” and “the leveret/hare”) in We Should All Be Birds by Brian Buckbee and Raising Hare by Chloe Dalton.

- Eating hash cookies in New York City in Women by Chloe Caldwell and How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney.

- A woman worries she’s left underclothes strewn about a room she’s about to show someone in one story of Single, Carefree, Mellow by Katherine Heiny and Days of Light by Megan Hunter.

The dialogue is italicized in Women by Chloe Caldwell and Days of Light by Megan Hunter.

The dialogue is italicized in Women by Chloe Caldwell and Days of Light by Megan Hunter.

- The ‘you know it when you see it’ definition (originally for pornography) is cited in Moderation by Elaine Castillo and Bookish by Lucy Mangan.

- Women (including the protagonist) weightlifting in a gym in Moderation by Elaine Castillo and All Fours by Miranda July.

- Miranda July, whose All Fours I was also reading at the time, was mentioned in Chinese Parents Don’t Say I Love You by Candice Chung.

- A sibling story and a mystical light: late last year into early 2025 I read The Snow Queen by Michael Cunningham, and then I recognized this type of moment in Days of Light by Megan Hunter.

- A lesbian couple with a furniture store in Carol [The Price of Salt] by Patricia Highsmith and one story of Are You Happy? by Lori Ostlund.

- Not being able to see the stars in Las Vegas because of light pollution was mentioned in The Wild Dark by Craig Childs, then in Moderation by Elaine Castillo.

- A gynaecology appointment scene in All Fours by Miranda July and How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney.

- An awkwardly tall woman in Heartwood by Amity Gaige, How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney, and Stoner by John Williams.

- The 9/11 memorial lights’ disastrous effect on birds is mentioned in The Wild Dark by Craig Childs and How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney.

- A car accident precipitated by an encounter with wildlife is key to the denouement in the novellas Women by Chloe Caldwell and Wild Boar by Hannah Lutz.

- The plot is set in motion by the death of an older brother by drowning, and pork chops are served to an unexpected dinner guest, in Bug Hollow by Michelle Huneven and Days of Light by Megan Hunter, both of which I was reading for Shelf Awareness review.

- Kids running around basically feral in a 1970s summer, and driving a box of human ashes around in Case Histories by Kate Atkinson and Bug Hollow by Michelle Huneven.

- A character becomes a nun in Case Histories by Kate Atkinson and Days of Light by Megan Hunter.

- Wrens nesting just outside one’s front door in Lifelines by Julian Hoffman and Little Mercy by Robin Walter.

- ‘The female Woody Allen’ is the name given to a character in Women by Chloe Caldwell and then a description (in a blurb) of French author Nolwenn Le Blevennec.

- A children’s birthday party scene in Single, Carefree, Mellow by Katherine Heiny and Friends and Lovers by Nolwenn Le Blevennec. A children’s party is also mentioned in Case Histories by Kate Atkinson and A Family Matter by Claire Lynch.

- A man who changes his child’s nappies, unlike his father – evidence of different notions of masculinity in different generations, in Case Histories by Kate Atkinson, What My Father and I Don’t Talk About, edited by Michele Filgate, and one piece in Beyond Touch Sites, edited by Wendy McGrath.

- What’s in a name? Repeated names I came across included Pansy (Case Histories by Kate Atkinson and Days of Light by Megan Hunter), Olivia (Case Histories by Kate Atkinson and A Family Matter by Claire Lynch), Jackson (Case Histories by Kate Atkinson and So Far Gone by Jess Walter), and Elias (Good Girl by Aria Aber and Dream State by Eric Puchner).

- The old wives’ tale that you should run in zigzags to avoid an alligator appeared in Alligator Tears by Edgar Gomez and then in The Girls Who Grow Big by Leila Mottley, both initially set in Florida.

- A teenage girl is groped in a nightclub in Good Girl by Aria Aber and Girl, 1983 by Linn Ullmann.

- Discussion of the extinction of human and animal cultures and languages in both Nature’s Genius by David Farrier and Lifelines by Julian Hoffman, two May 2025 releases I was reading at the same time.

- In Body: My Life in Parts by Nina B. Lichtenstein, she mentions Linn Ullmann – who lived on her street in Oslo and went to the same school (not favourably – the latter ‘stole’ her best friend!); at the same time, I was reading Linn Ullmann’s Girl, 1983! And then, in both books, the narrator recalls getting a severe sunburn.

On the same day, I read about otter sightings in Lifelines by Julian Hoffman and Spring by Michael Morpurgo. The next day, I read about nesting swallows in both books.

On the same day, I read about otter sightings in Lifelines by Julian Hoffman and Spring by Michael Morpurgo. The next day, I read about nesting swallows in both books.

- The Salish people (Indigenous to North America) are mentioned in Lifelines by Julian Hoffman, Dream State by Eric Puchner (where Salish, the town in Montana, is also a setting), and So Far Gone by Jess Walter.

- Driving into a compound of extremists, and then the car being driven away by someone who’s not the owner, in Dream State by Eric Puchner and So Far Gone by Jess Walter.

- A woman worries about her (neurodivergent) husband saying weird things at a party in The Honesty Box by Lucy Brazier and Normally Weird and Weirdly Normal by Robin Ince.

- Shooting raccoons in Ginseng Roots by Craig Thompson and So Far Gone by Jess Walter. (Raccoons also feature in Dream State by Eric Puchner.)

- A graphic novelist has Hollywood types adding (or at least threatening to add) wholly unsuitable supernatural elements to their plots in Spent by Alison Bechdel and Ginseng Roots by Craig Thompson.

- A novel in which a character named Dawn has to give up her daughter in the early 1980s, one right after the other: A Family Matter by Claire Lynch, followed by Love Forms by Claire Adam.

- A girl barricades her bedroom door for fear of her older brother in Love Forms by Claire Adam and Sleep by Honor Jones.

- A scene of an only child learning that her mother had a hysterectomy and so couldn’t have any more children in Dream Count by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and Other People’s Mothers by Julie Marie Wade.

- An African hotel cleaner features in Dream Count by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and The Hotel by Daisy Johnson.

- Annie Dillard’s essay “Living Like Weasels” is mentioned in Nature’s Genius by David Farrier and The Dry Season by Melissa Febos.

- A woman assembles an inventory of her former lovers in Dream Count by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and The Dry Season by Melissa Febos.

What’s the weirdest reading coincidence you’ve had lately?

A remote artist’s studio and severed fingers in Old Soul by Susan Barker and We Do Not Part by Han Kang.

A remote artist’s studio and severed fingers in Old Soul by Susan Barker and We Do Not Part by Han Kang.

New York City tourist slogans in Apple of My Eye by Helene Hanff and How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney.

New York City tourist slogans in Apple of My Eye by Helene Hanff and How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney.

A stalker-ish writing student who submits an essay to his professor that seems inappropriately personal about her in one story of Are You Happy? by Lori Ostlund and If You Love It, Let It Kill You by Hannah Pittard.

A stalker-ish writing student who submits an essay to his professor that seems inappropriately personal about her in one story of Are You Happy? by Lori Ostlund and If You Love It, Let It Kill You by Hannah Pittard.

A writing professor knows she’s a hypocrite for telling her students what (not) to do and then (not) doing it herself in Trying by Chloé Caldwell and If You Love It, Let It Kill You by Hannah Pittard. These two books also involve a partner named B (or Bruce), metafiction, porch drinks with parents, and the observation that a random statement sounds like a book title.

A writing professor knows she’s a hypocrite for telling her students what (not) to do and then (not) doing it herself in Trying by Chloé Caldwell and If You Love It, Let It Kill You by Hannah Pittard. These two books also involve a partner named B (or Bruce), metafiction, porch drinks with parents, and the observation that a random statement sounds like a book title.

Shalimar perfume is mentioned in Scaffolding by Lauren Elkin and Chopping Onions on My Heart by Samantha Ellis.

Shalimar perfume is mentioned in Scaffolding by Lauren Elkin and Chopping Onions on My Heart by Samantha Ellis.