Four (Almost) One-Sitting Novellas by Blackburn, Murakami, Porter & School of Life (#NovNov25)

I never believe people who say they read 300-page novels in a sitting. How is that possible?! I’m a pretty slow reader, I like to bounce between books rather than read one exclusively, and I often have a hot drink to hand beside my book stack, so I’d need a bathroom break or two. I also have a young cat who doesn’t give me much peace. But 100 pages or thereabouts? I at least have a fighting chance of finishing a novella in one go. Although I haven’t yet achieved a one-sitting read this month, it’s always the goal: to carve out the time and be engrossed such that you just can’t put a book down. I’ll see if I can manage it before November is over.

A couple of longish car rides last weekend gave me the time to read most of three of these, and the next day I popped the other in my purse for a visit to my favourite local coffee shop. I polished them all off later in the week. I have a mini memoir in pets, a surreal Japanese story with illustrations, an innovative modern classic about bereavement, and a set of short essays about money and commodification.

My Animals and Other Family by Julia Blackburn; illus. Herman Makkink (2007)

In five short autobiographical essays, Blackburn traces her life with pets and other domestic animals. Guinea pigs taught her the facts of life when she was the pet monitor for her girls’ school – and taught her daughter the reality of death when they moved to the country and Galaxy sired a kingdom of outdoor guinea pigs. They also raised chickens, then adopted two orphaned fox cubs; this did not end well. There are intriguing hints of Blackburn’s childhood family dynamic, which she would later write about in the memoir The Three of Us: Her father was an alcoholic poet and her mother a painter. It was not a happy household and pets provided comfort as well as companionship. “I suppose tropical fish were my religion,” she remarks, remembering all the time she devoted to staring at the aquarium. Jason the spaniel was supposed to keep her safe on walks, but his presence didn’t deter a flasher (her parents’ and a policeman’s reactions to hearing the story are disturbingly blasé). My favourite piece was the first, “A Bushbaby from Harrods”: In the 1950s, the department store had a Zoo that sold exotic pets. Congo the bushbaby did his business all over her family’s flat but still was “the first great love of my life,” Blackburn insists. This was pleasant but won’t stay with me. (New purchase – remainder copy from Hay Cinema Bookshop, 2025) [86 pages]

In five short autobiographical essays, Blackburn traces her life with pets and other domestic animals. Guinea pigs taught her the facts of life when she was the pet monitor for her girls’ school – and taught her daughter the reality of death when they moved to the country and Galaxy sired a kingdom of outdoor guinea pigs. They also raised chickens, then adopted two orphaned fox cubs; this did not end well. There are intriguing hints of Blackburn’s childhood family dynamic, which she would later write about in the memoir The Three of Us: Her father was an alcoholic poet and her mother a painter. It was not a happy household and pets provided comfort as well as companionship. “I suppose tropical fish were my religion,” she remarks, remembering all the time she devoted to staring at the aquarium. Jason the spaniel was supposed to keep her safe on walks, but his presence didn’t deter a flasher (her parents’ and a policeman’s reactions to hearing the story are disturbingly blasé). My favourite piece was the first, “A Bushbaby from Harrods”: In the 1950s, the department store had a Zoo that sold exotic pets. Congo the bushbaby did his business all over her family’s flat but still was “the first great love of my life,” Blackburn insists. This was pleasant but won’t stay with me. (New purchase – remainder copy from Hay Cinema Bookshop, 2025) [86 pages] ![]()

Super-Frog Saves Tokyo by Haruki Murakami; illus. Seb Agresti and Suzanne Dean (2000, 2001; this edition 2025)

[Translated from Japanese by Jay Rubin]

This short story first appeared in English in GQ magazine in 2001 and was then included in Murakami’s collection after the quake, a response to the Kobe earthquake of 1995. “Katigiri found a giant frog waiting for him in his apartment,” it opens. The six-foot amphibian knows that an earthquake will hit Tokyo in three days’ time and wants the middle-aged banker to help him avert disaster by descending into the realm below the bank and doing battle with Worm. Legend has it that the giant worm’s anger causes natural disasters. Katigiri understandably finds it difficult to believe what’s happening, so Frog earns his trust by helping him recover a troublesome loan. Whether Frog is real or not doesn’t seem to matter; either way, imagination saves the city – and Katigiri when he has a medical crisis. I couldn’t help but think of Rachel Ingalls’ Mrs. Caliban (one of my NovNov reads last year). While this has been put together as an appealing standalone volume and was significantly more readable than any of Murakami’s recent novels that I’ve tried, I felt a bit cheated by the it-was-all-just-a-dream motif. (Public library) [86 pages]

This short story first appeared in English in GQ magazine in 2001 and was then included in Murakami’s collection after the quake, a response to the Kobe earthquake of 1995. “Katigiri found a giant frog waiting for him in his apartment,” it opens. The six-foot amphibian knows that an earthquake will hit Tokyo in three days’ time and wants the middle-aged banker to help him avert disaster by descending into the realm below the bank and doing battle with Worm. Legend has it that the giant worm’s anger causes natural disasters. Katigiri understandably finds it difficult to believe what’s happening, so Frog earns his trust by helping him recover a troublesome loan. Whether Frog is real or not doesn’t seem to matter; either way, imagination saves the city – and Katigiri when he has a medical crisis. I couldn’t help but think of Rachel Ingalls’ Mrs. Caliban (one of my NovNov reads last year). While this has been put together as an appealing standalone volume and was significantly more readable than any of Murakami’s recent novels that I’ve tried, I felt a bit cheated by the it-was-all-just-a-dream motif. (Public library) [86 pages] ![]()

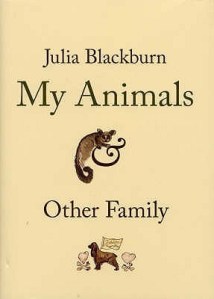

Grief Is the Thing with Feathers by Max Porter (2015)

A reread – I reviewed this for Shiny New Books when it first came out and can’t better what I said then. “The novel is composed of three first-person voices: Dad, Boys (sometimes singular and sometimes plural) and Crow. The father and his two young sons are adrift in mourning; the boys’ mum died in an accident in their London flat. The three narratives resemble monologues in a play, with short lines often laid out on the page more like stanzas of a poem than prose paragraphs.” What impressed me most this time was the brilliant mash-up of allusions and genres. The title: Emily Dickinson. The central figure: Ted Hughes’s Crow. The setup: Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven” – while he’s grieving his lost love, a man is visited by a black bird that won’t leave until it’s delivered its message. (A raven cronked overhead as I was walking to get my cappuccino.) I was less dazzled by the actual writing, though, apart from a few very strong lines about the nature of loss, e.g. “Moving on, as a concept, is for stupid people, because any sensible person knows grief is a long-term project.” I have a feeling this would be better experienced in other media (such as audio, or the play version). I do still appreciate it as a picture of grief over time, however. Porter won the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award as well as the Dylan Thomas Prize. (Secondhand – Gifted by a friend as part of a trip to Community Furniture Project, Newbury last year; I’d resold my original hardback copy – more fool me!) [114 pages]

A reread – I reviewed this for Shiny New Books when it first came out and can’t better what I said then. “The novel is composed of three first-person voices: Dad, Boys (sometimes singular and sometimes plural) and Crow. The father and his two young sons are adrift in mourning; the boys’ mum died in an accident in their London flat. The three narratives resemble monologues in a play, with short lines often laid out on the page more like stanzas of a poem than prose paragraphs.” What impressed me most this time was the brilliant mash-up of allusions and genres. The title: Emily Dickinson. The central figure: Ted Hughes’s Crow. The setup: Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven” – while he’s grieving his lost love, a man is visited by a black bird that won’t leave until it’s delivered its message. (A raven cronked overhead as I was walking to get my cappuccino.) I was less dazzled by the actual writing, though, apart from a few very strong lines about the nature of loss, e.g. “Moving on, as a concept, is for stupid people, because any sensible person knows grief is a long-term project.” I have a feeling this would be better experienced in other media (such as audio, or the play version). I do still appreciate it as a picture of grief over time, however. Porter won the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award as well as the Dylan Thomas Prize. (Secondhand – Gifted by a friend as part of a trip to Community Furniture Project, Newbury last year; I’d resold my original hardback copy – more fool me!) [114 pages]

My original rating (in 2015): ![]()

My rating now: ![]()

Why We Hate Cheap Things by The School of Life (2017)

I’m generally a fan of the high-brow self-help books The School of Life produces, but these six micro-essays feel like cast-offs from a larger project. The title essay explores the link between the cost of an item or experience and how much we value it – with reference to pineapples and paintings. The other essays decry the fact that money doesn’t get fairly distributed, such that craftspeople and arts graduates often struggle financially when their work and minds are exactly what we should be valuing as a society. Fair enough … but any suggestions for how to fix the situation?! I’m finding Robin Wall Kimmerer’s The Serviceberry, which is also on a vaguely economic theme, much more engaging and profound. There’s no author listed for this volume, but as The School of Life is Alain de Botton’s brainchild, I’m guessing he had a hand. Perhaps he’s been cancelled? This raises a couple of interesting questions, but overall you’re probably better off spending the time with something more in depth. (Little Free Library) [78 pages]

I’m generally a fan of the high-brow self-help books The School of Life produces, but these six micro-essays feel like cast-offs from a larger project. The title essay explores the link between the cost of an item or experience and how much we value it – with reference to pineapples and paintings. The other essays decry the fact that money doesn’t get fairly distributed, such that craftspeople and arts graduates often struggle financially when their work and minds are exactly what we should be valuing as a society. Fair enough … but any suggestions for how to fix the situation?! I’m finding Robin Wall Kimmerer’s The Serviceberry, which is also on a vaguely economic theme, much more engaging and profound. There’s no author listed for this volume, but as The School of Life is Alain de Botton’s brainchild, I’m guessing he had a hand. Perhaps he’s been cancelled? This raises a couple of interesting questions, but overall you’re probably better off spending the time with something more in depth. (Little Free Library) [78 pages] ![]()

I learned about this from one of May Sarton’s journals, which shares its concern with ageing and selfhood. The author was an American suffragist, playwright, mother and analytical psychologist who trained under Jung and lived in England and Scotland with her Scottish husband. She kept this notebook while she was 82, partly while recovering from gallbladder surgery. It’s written in short, sometimes aphoristic paragraphs. While I appreciated her thoughts on suffering, developing “hardihood,” the simplicity that comes with giving up many cares and activities, and the impossibility of solving “one’s own incorrigibility,” I found this somewhat rambly and abstract, especially when she goes off on a dated tangent about the equality of the sexes. (Free from The Book Thing of Baltimore)

I learned about this from one of May Sarton’s journals, which shares its concern with ageing and selfhood. The author was an American suffragist, playwright, mother and analytical psychologist who trained under Jung and lived in England and Scotland with her Scottish husband. She kept this notebook while she was 82, partly while recovering from gallbladder surgery. It’s written in short, sometimes aphoristic paragraphs. While I appreciated her thoughts on suffering, developing “hardihood,” the simplicity that comes with giving up many cares and activities, and the impossibility of solving “one’s own incorrigibility,” I found this somewhat rambly and abstract, especially when she goes off on a dated tangent about the equality of the sexes. (Free from The Book Thing of Baltimore)

“Activism is not a journey to the corner store, it is a plunge into the unknown. The future is always dark.” This resonated with the

“Activism is not a journey to the corner store, it is a plunge into the unknown. The future is always dark.” This resonated with the

Tangye wrote a series of cozy animal books similar to Doreen Tovey’s. He and his wife Jean ran a flower farm in Cornwall and had a succession of cats, along with donkeys and a Muscovy duck named Boris. After the death of their beloved cat Monty, Jean wanted a kitten for Christmas but Tangye, who considered himself a one-cat man rather than a wholesale cat lover, hesitated. The matter was decided for them when a little black stray started coming round and soon made herself at home. (Her name is a tribute to the Dalai Lama’s safe flight from Tibet.) Mild adventures ensue, such as Lama going down a badger sett and Jeannie convincing herself that she’s identified another stray as Lama’s mother. Pleasant, if slight; I’ll read more by Tangye. (From Kennet Centre free bookshop)

Tangye wrote a series of cozy animal books similar to Doreen Tovey’s. He and his wife Jean ran a flower farm in Cornwall and had a succession of cats, along with donkeys and a Muscovy duck named Boris. After the death of their beloved cat Monty, Jean wanted a kitten for Christmas but Tangye, who considered himself a one-cat man rather than a wholesale cat lover, hesitated. The matter was decided for them when a little black stray started coming round and soon made herself at home. (Her name is a tribute to the Dalai Lama’s safe flight from Tibet.) Mild adventures ensue, such as Lama going down a badger sett and Jeannie convincing herself that she’s identified another stray as Lama’s mother. Pleasant, if slight; I’ll read more by Tangye. (From Kennet Centre free bookshop)  Like Tangye, Gallico is known for writing charming animal books, but fables rather than memoirs. Set in postwar Assisi, Italy, this stars Pepino, a 10-year-old orphan boy who runs errands with his donkey Violetta to earn his food and board. When Violetta falls ill, he dreads losing not just his livelihood but also his only friend in the world. But the powers that be won’t let him bring her into the local church so that he can pray to St. Francis for her healing. Pepino takes to heart the maxim an American corporal gave him – “don’t take no for an answer” – and takes his suit all the way to the pope. This story of what faith can achieve just manages to avoid being twee. (From Kennet Centre free bookshop)

Like Tangye, Gallico is known for writing charming animal books, but fables rather than memoirs. Set in postwar Assisi, Italy, this stars Pepino, a 10-year-old orphan boy who runs errands with his donkey Violetta to earn his food and board. When Violetta falls ill, he dreads losing not just his livelihood but also his only friend in the world. But the powers that be won’t let him bring her into the local church so that he can pray to St. Francis for her healing. Pepino takes to heart the maxim an American corporal gave him – “don’t take no for an answer” – and takes his suit all the way to the pope. This story of what faith can achieve just manages to avoid being twee. (From Kennet Centre free bookshop)

Reprinted as a stand-alone pamphlet to celebrate the author’s 70th birthday, this is about a waitress who on her 20th birthday is given the unwonted task of taking dinner up to the restaurant owner, who lives above the establishment. He is taken with the young woman and offers to grant her one wish. We never hear exactly what that wish was. It’s now more than 10 years later and she’s recalling the occasion for a friend, who asks her if the wish came true and whether she regrets what she requested. She surveys her current life and says that it remains to be seen whether her wish will be fulfilled; I could only assume that she wished for happiness, which is shifting and subjective. Encountering this in a larger collection would be fine, but it wasn’t particularly worth reading on its own. (Public library)

Reprinted as a stand-alone pamphlet to celebrate the author’s 70th birthday, this is about a waitress who on her 20th birthday is given the unwonted task of taking dinner up to the restaurant owner, who lives above the establishment. He is taken with the young woman and offers to grant her one wish. We never hear exactly what that wish was. It’s now more than 10 years later and she’s recalling the occasion for a friend, who asks her if the wish came true and whether she regrets what she requested. She surveys her current life and says that it remains to be seen whether her wish will be fulfilled; I could only assume that she wished for happiness, which is shifting and subjective. Encountering this in a larger collection would be fine, but it wasn’t particularly worth reading on its own. (Public library)