My Life in Book Titles from 2024

As usual for January, I’m in the middle of lots of books but hardly finishing anything, so consider this a placeholder until my Love Your Library and January releases posts later in the month. It’s a fun meme that goes around every year; I first spotted it on Annabel’s blog and Susan also took part. I’ve never had a go before but when I looked at the prompts I realized some books I read in 2024 have titles that work awfully well. Links are to my reviews.

In high school I was [one of the] Remarkably Bright Creatures (Shelby Van Pelt)

In high school I was [one of the] Remarkably Bright Creatures (Shelby Van Pelt)

- People might be surprised by All the Beauty in the World (Patrick Bringley)

- I will never be A Spy in the House of Love (Anaïs Nin)

My fantasy job is To Be a Cat (Matt Haig)

My fantasy job is To Be a Cat (Matt Haig)

- At the end of a long day, I need [a] Cocktail (Lisa Alward)

- I hate being [an] Exhibit (R.O. Kwon)

- Wish I had Various Miracles (Carol Shields)

- My family reunions are The Grief Cure (Cory Delistraty)

At a party you’d find me with Orphans of the Carnival (Carol Birch)

At a party you’d find me with Orphans of the Carnival (Carol Birch)

- I’ve never been to Jungle House (Julianne Pachico)

A happy day includes The Old Haunts (Allan Radcliffe)

A happy day includes The Old Haunts (Allan Radcliffe)

- Motto I live by: I’m Mostly Here to Enjoy Myself (Glynnis MacNicol)

On my bucket list is A Bookshop of One’s Own (Jane Cholmeley)

On my bucket list is A Bookshop of One’s Own (Jane Cholmeley)

- In my next life, I want to have A House Full of Daughters (Juliet Nicolson)

Reading about Mothers and Motherhood: Cosslett, Cusk, Emma Press Poetry, Heti, and Pachico

It was (North American) Mother’s Day at the weekend, an occasion I have complicated feelings about now that my mother is gone. But I don’t think I’ll ever stop reading and writing about mothering. At first I planned to divide my recent topical reads (one a reread) into two sets, one for ambivalence about becoming a mother and the other for mixed feelings about one’s mother. But the two are intertwined – especially in the poetry anthology I consider below – such that they feel more like facets of the same experience. I also review two memoirs (one classic; one not so much) and two novels (autofiction vs. science fiction).

The Year of the Cat: A Love Story by Rhiannon Lucy Cosslett (2023)

This was on my Most Anticipated list last year. A Covid memoir that features adopting a cat and agonizing over the question of whether to have a baby sounded right up my street. And in the earlier pages, in which Cosslett brings Mackerel the kitten home during the first lockdown and interrogates the stereotype of the crazy cat lady from the days of witches’ familiars onwards, it indeed seemed to be so. But the further I got, the more my pace through the book slowed to a limp; it took me 10 months to read, in fits and starts.

I’ve struggled to pinpoint what I found so off-putting, but I have a few hypotheses: 1) By the time I got hold of this, I’d tired of Covid narratives. 2) Fragmentary narratives can seem like profound reflections on subjectivity and silences. But Cosslett’s strategy of bouncing between different topics – worry over her developmentally disabled brother, time working as an au pair in France, PTSD from an attempted strangling by a stranger in London and being in Paris on the day of the Charlie Hebdo terrorist attack – with every page or even every paragraph, feels more like laziness or arrogance. Of course the links are there; can’t you see them?

I’ve struggled to pinpoint what I found so off-putting, but I have a few hypotheses: 1) By the time I got hold of this, I’d tired of Covid narratives. 2) Fragmentary narratives can seem like profound reflections on subjectivity and silences. But Cosslett’s strategy of bouncing between different topics – worry over her developmentally disabled brother, time working as an au pair in France, PTSD from an attempted strangling by a stranger in London and being in Paris on the day of the Charlie Hebdo terrorist attack – with every page or even every paragraph, feels more like laziness or arrogance. Of course the links are there; can’t you see them?

3) Cosslett claims to reject clichéd notions about pets being substitutes for children, then goes right along with them by presenting Mackerel as an object of mothering (“there is something about looking after her that has prodded the carer in me awake”) and setting up a parallel between her decision to adopt the kitten and her decision to have a child. “Though I had all these very valid reasons not to get a cat, I still wanted one,” she writes early on. And towards the end, even after she’s considered all the ‘very valid reasons’ not to have a baby, she does anyway. “I need to find another way of framing it, if I am to do it,” she says. So she decides that it’s an expression of bravery, proof of overcoming trauma. I was unconvinced. When people accuse memoirists of being navel-gazing, this is just the sort of book they have in mind. I wonder if those familiar with her Guardian journalism would agree. (Public library)

A Life’s Work: On Becoming a Mother by Rachel Cusk (2001)

When this was first published, Cusk was vilified for “hating” her child – that is, for writing honestly about the bewilderment and misery of early motherhood. We’ve moved on since then. Now women are allowed to admit that it’s not all cherubs and lullabies. I suspect what people objected to was the unemotional tone: Cusk writes like an anthropologist arriving in a new land. The style is similar to her novels’ in that she can seem detached because of her dry wit, elevated diction and frequent literary allusions.

When this was first published, Cusk was vilified for “hating” her child – that is, for writing honestly about the bewilderment and misery of early motherhood. We’ve moved on since then. Now women are allowed to admit that it’s not all cherubs and lullabies. I suspect what people objected to was the unemotional tone: Cusk writes like an anthropologist arriving in a new land. The style is similar to her novels’ in that she can seem detached because of her dry wit, elevated diction and frequent literary allusions.

I understand that crying, being the baby’s only means of communication, has any number of causes, which it falls to me, as her chief companion and link to the world, to interpret.

Have you taken her to toddler group, the health visitor enquired. I had not. Like vaccinations and mother and baby clinics, the notion instilled in me a deep administrative terror.

We [new parents] are heroic and cruel, authoritative and then servile, cleaving to our guesses and inspirations and bizarre rituals in the absence of any real understanding of what we are doing or how it should properly be done.

She approaches mumsy things as an outsider, clinging to intellectualism even though it doesn’t seem to apply to this new world of bodily obligation, “the rambling dream of feeding and crying that my life has become.” By the end of the book, she does express love for and attachment to her daughter, built up over time and through constant presence. But she doesn’t downplay how difficult it was. “For the first year of her life work and love were bound together, fiercely, painfully.” This is a classic of motherhood literature, and more engaging than anything else I’ve read by Cusk. (Secondhand purchase – Awesomebooks.com)

The Emma Press Anthology of Motherhood, ed. by Rachel Piercey and Emma Wright (2014)

There’s a great variety of subject matter and tone here, despite the apparently narrow theme. There are poems about pregnancy (“I have a comfort house inside my body” by Ikhda Ayuning Maharsi), childbirth (“The Tempest” by Melinda Kallismae) and new motherhood, but also pieces imagining the babies that never were (“Daughters” by Catherine Smith) or revealing the complicated feelings adults have towards their mothers.

“All My Mad Mothers” by Jacqueline Saphra depicts a difficult bond through absurdist metaphors: “My mother was so hard to grasp: once we found her in a bath / of olive oil, or was it sesame, her skin well-slicked / … / to ease her way into this world. Or out of it.” I also loved her evocation of a mother–daughter relationship through a rundown of a cabinet’s contents in “My Mother’s Bathroom Armoury.”

In “My Mother Moves into Adolescence,” Deborah Alma expresses exasperation at the constant queries and calls for help from someone unconfident in English. “This, then, is how you should pray” by Flora de Falbe cleverly reuses the structure of the Lord’s Prayer as she sees her mother returning to independent life and a career as her daughter prepares to leave home. “I will hold you / as you held me / my mother – / yours are the bathroom catalogues / and the whole of a glorious future.”

In “My Mother Moves into Adolescence,” Deborah Alma expresses exasperation at the constant queries and calls for help from someone unconfident in English. “This, then, is how you should pray” by Flora de Falbe cleverly reuses the structure of the Lord’s Prayer as she sees her mother returning to independent life and a career as her daughter prepares to leave home. “I will hold you / as you held me / my mother – / yours are the bathroom catalogues / and the whole of a glorious future.”

I connected with these perhaps more so than the poems about becoming a mother, but there are lots of strong entries and very few unmemorable ones. Even within the mothers’ testimonials, there is ambivalence: the visceral vocabulary in “Collage” by Anna Kisby is rather morbid, partway to gruesome: “You look at me // like liver looks at me, like heart. You are familiar as innards. / In strip-light I clean your first shit. I’m not sure I do it right. / It sticks to me like funeral silk. … There is a window // guillotined into the wall. I scoop you up like a clod.”

A favourite pair: “Talisman” by Anna Kirk and “Grasshopper Warbler” by Liz Berry, on facing pages, for their nature imagery. “Child, you are grape / skins stretched over fishbones. … You are crab claws unfurling into cabbage leaves,” Kirk writes. Berry likens pregnancy to patient waiting for an elusive bird by a reedbed. (Free copy – newsletter giveaway)

Motherhood by Sheila Heti (2018)

I first read this nearly six years ago (see my original review), when I was 34; I’m now 40 and pretty much decided against having children, but FOMO is a lingering niggle. Even though I already owned it in hardback, I couldn’t resist picking up a nearly new paperback I saw going for 50 pence in a charity shop, if only for the Leanne Shapton cover – her simple, elegant watercolour style is instantly recognizable. Having a different copy also provided some novelty for my reread, which is ongoing; I’m about 80 pages from the end.

I’m not finding Heti’s autofiction musings quite as profound this time around, and I can’t deny that the book is starting to feel repetitive, but I’ve still marked more than a dozen passages. Pondering whether to have children is only part of the enquiry into what a woman artist’s life should be. The intergenerational setup stands out to me again as Heti compares her Holocaust survivor grandmother’s short life with her mother’s practical career and her own creative one.

I’m not finding Heti’s autofiction musings quite as profound this time around, and I can’t deny that the book is starting to feel repetitive, but I’ve still marked more than a dozen passages. Pondering whether to have children is only part of the enquiry into what a woman artist’s life should be. The intergenerational setup stands out to me again as Heti compares her Holocaust survivor grandmother’s short life with her mother’s practical career and her own creative one.

For the past month or so, I’ve also been reading Alphabetical Diaries, so you could say that I’m pretty Heti-ed out right now, but I do so admire her for writing exactly what she wants to and sticking to no one else’s template. People probably react against Heti’s work as self-indulgent in the same way I did with Cosslett’s, but the former’s shtick works for me. (Secondhand purchase – Bas Books & Home, Newbury)

A few of the passages that have most struck me on this second reading:

I think that is how childbearing feels to me: a once-necessary, now sentimental gesture.

I don’t want ‘not a mother’ to be part of who I am—for my identity to be the negative of someone else’s positive identity.

The whole world needs to be mothered. I don’t need to invent a brand new life to give the warming effect to my life I imagine mothering will bring.

I have to think, If I wanted a kid, I already would have had one by now—or at least I would have tried.

Jungle House by Julianne Pachico (2023)

{BEWARE SPOILERS}

Pachico’s third novel is closer to sci-fi than I might have expected. Apart from Lena, the protagonist, all the major characters are machines or digital recreations: AI, droids, a drone, or a holograph of the consciousness of a dead girl. “Mother” is the AI security system that controls Jungle House, the Morel family’s vacation home in a country that resembles Colombia, where Pachico grew up and set her first two books. Lena, as the human caretaker, is forever grateful to Mother for rescuing her as a baby after the violent death of her parents, who were presumed rebels.

Pachico’s third novel is closer to sci-fi than I might have expected. Apart from Lena, the protagonist, all the major characters are machines or digital recreations: AI, droids, a drone, or a holograph of the consciousness of a dead girl. “Mother” is the AI security system that controls Jungle House, the Morel family’s vacation home in a country that resembles Colombia, where Pachico grew up and set her first two books. Lena, as the human caretaker, is forever grateful to Mother for rescuing her as a baby after the violent death of her parents, who were presumed rebels.

Mother is exacting but mercurial, strict about cleanliness yet apt to forget or overlook things during one of her “spells.” Lena pushes the boundaries of her independence, believing that Mother only wants to protect her but still longing to explore the degraded wilderness beyond the compound.

Mother was right, because Mother was always right about these kinds of things. The world was a complicated place, and Mother understood it much better than she did.

In the house, there was no privacy. In the house, Mother saw all.

Mother was Lena’s world. And Lena, in turn, was hers. No matter how angry they got at each other, no matter how much they fought, no matter the things that Mother did or didn’t do … they had each other.

It takes a while to work out just how tech-reliant this scenario is, what the repeated references to “the pit bull” are about, and how Lena emulated and resented Isabella, the Morel daughter, in equal measure. Even creepier than the satellites’ plan to digitize humans is the fact that Isabella’s security drone, Anton, can fabricate recorded memories. This reminded me a lot of Klara and the Sun. Tech themes aren’t my favourite, but I ultimately thought of this as an allegory of life with a narcissistic mother and the child’s essential task of breaking free. It’s not clinical and contrived, though; it’s a taut, subtle thriller with an evocative setting. (Public library)

See also: “Three on a Theme: Matrescence Memoirs”

Does one or more of these books take your fancy?

The Booker Prize 2023 Ceremony

Yesterday evening Eleanor Franzen of Elle Thinks and I had the enormous pleasure of attending the Booker Prize awards ceremony at Old Billingsgate in London. I won tickets through “The Booker Prize Book Club” Facebook group, which launched just 10 or so weeks ago but has already garnered over 6000 members from around the world. They ran a competition for shortlist book reviews and probably did not attract nearly as many entries as they expected to. This probably worked to my advantage, but as it’s the only prize I can recall winning for my writing, I am going to take it as a compliment nonetheless! I submitted versions of my reviews of If I Survive You and Western Lane – the only shortlistees that I’ve read – and it was the latter that won us tickets.

We arrived at the venue 15 minutes before the doors opened, sheltering from the drizzle under an overhang and keeping a keen eye on arrivals (Paul Lynch and sodden Giller Prize winner Sarah Bernstein, her partner wearing both a kilt and their several-week-old baby). Elle has a gift for small talk and we had a nice little chat with Jonathan Escoffery and his 4th Estate publicist before they were whisked inside. His head was spinning from the events of the week, including being part of a Booker delegation that met Queen Camilla.

There was a glitzy atmosphere, with a photographer-surrounded red carpet and large banners for each shortlisted novel along the opposite wall, plus an exhibit of the hand-bound editions created for each book. We enjoyed some glasses of champagne and canapés (the haddock tart was the winner) and collared Eric Karl Anderson of Lonesome Reader. It was lovely to catch up with him and Eleanor and do plenty of literary celebrity spotting: Graeme Macrae Burnet, Eleanor Catton, judge Mary Jean Chan, Natalie Haynes, Alan Hollinghurst, Anna James, Jean McNeil, Johanna Thomas-Corr (literary editor of the Sunday Times) and Sarah Waters. Later we were also able to chat with Julianne Pachico, our Sunday Times Young Writer Award shadow panel winner from 2017. She has recently gotten married and released her third novel.

We were allocated to Table 11 in the front right corner. Also at our table were some Booker Prize editorial staff members, the other competition winner (for a video review) and her guest, an Instagram influencer, a Reading Agency employee, and several more people. The three-course dinner was of a very high standard for mass catering and the wine flowed generously. I thoroughly enjoyed my meal. Afterward we had a bit of time for taking red carpet photos and one of Eleanor with the banner for our predicted winner, Prophet Song.

Some of you may have watched the YouTube livestream, or listened to the Radio 4 live broadcast. Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe’s speech was a highlight. She spoke about the secret library at the Iranian prison where she was held for six years. Doctor Thorne by Anthony Trollope, War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy, The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood (there was a long waiting list among the prisoners and wardens, she said), and especially The Return by Hisham Matar meant a lot to her. From earlier on in the evening, I also enjoyed judge Adjoa Andoh’s dramatic reading of an excerpt from Possession in honour of the late Booker winner A.S. Byatt, and Shehan Karunatilaka’s tongue-in-cheek reflections on winning the Booker – he warned the next winner that they won’t write a word for a whole year.

There was a real variety of opinion in the room as to who would win. Earlier in the evening we’d spoken to people who favoured Western Lane, This Other Eden and The Bee Sting. But both Elle and I were convinced that Prophet Song would take home the trophy, and so it did. Despite his genuine display of shock, Paul Lynch was well prepared with an excellent speech in which he cited the apocrypha and Albert Camus. In a rapid-fire interview with host Samira Ahmed, he added that he can still remember sitting down and weeping after finishing The Mayor of Casterbridge, age 15 or 16, and hopes that his work might elicit similar emotion. I’m not sure that I plan on reading it myself, but from what I’ve heard it’s a powerfully convincing dystopian novel that brings political and social collapse home in a realistic way.

All in all, a great experience for which I am very grateful! (Thanks to Eleanor for all the photos.)

Have you read Prophet Song? Did you expect it to win the Booker Prize?

Love Your Library, June 2023

Thanks, as always, to Elle for her participation, and to Laura and Naomi for their reviews of books borrowed from libraries. Ever since she was our Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award shadow panel winner, I’ve followed Julianne Pachico’s blog. A recent post lists books she currently has from the library. I like her comment that borrowing books “is definitely scratching that dopamine itch for me”! On Instagram I spotted this post celebrating both libraries and Pride Month.

And so to my reading and borrowing since last time.

Most of my reservations seemed to come in all at once, right before we left for Scotland, so I’m taking a giant pile along with me (luckily, we’re traveling by car so I don’t have space or weight restrictions) and will see which I can get to, while also fitting in Scotland-themed reads, June review copies, e-books for paid review, and a few of my 20 Books of Summer!

READ

- Rainbow Rainbow: Stories by Lydia Conklin

- The Greengage Summer by Rumer Godden

- Under the Rainbow by Celia Laskey

- Scattered Showers: Stories by Rainbow Rowell

- A Cat in the Window by Derek Tangye

- Cats in Concord by Doreen Tovey

CURRENTLY READING

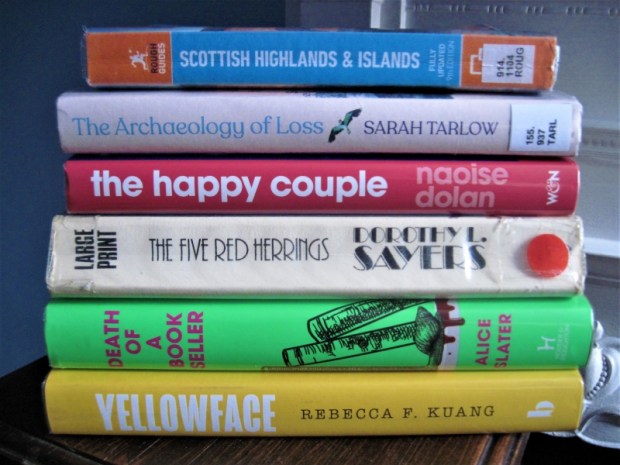

- The Happy Couple by Naoise Dolan

- The Gifts by Liz Hyder

- Milk by Alice Kinsella

- Yellowface by Rebecca F. Kuang

- Music in the Dark by Sally Magnusson

- Five Red Herrings by Dorothy L. Sayers

- Death of a Bookseller by Alice Slater

- The Archaeology of Loss by Sarah Turlow

- The Legacy of Elizabeth Pringle by Kirsty Wark

CHECKED OUT, TO BE READ

RETURNED UNREAD

- Pod by Laline Paull – I wanted to give this a try because it made the Women’s Prize shortlist, but I looked at the first few pages and skimmed through the rest and knew I just couldn’t take it seriously. I mean, look at lines like these: “The Rorqual wanted to laugh, but it was serious. The dolphin had been in some physical horror and had lost his mind. Google could not bear his mistake. The sound he raced toward was not Base, but this thing, this creature, he had never before encountered.”

What have you been reading or reviewing from the library recently?

Share a link to your own post in the comments. Feel free to use the above image. The hashtag is #LoveYourLibrary.

4 Reasons to Love Julie Buntin’s Debut Novel, Marlena

I managed to miss Marlena when it first came out last year; luckily, I had another chance at reading it when it was released in paperback a couple of months ago. It bears some thematic similarities to Emma Cline’s The Girls, Rosalie Knecht’s Relief Map, Andrée Michaud’s The Last Summer, Julianne Pachico’s The Lucky Ones and especially Emily Fridlund’s History of Wolves, but Marlena is a cut above. It’s basically a flawless debut, one I can’t recommend too highly. Occasionally I weary of writing straightforward reviews – let’s be honest, you get tired of reading them, too – so I’m returning to a format I last used for my review of The Animators and pulling out four reasons why you must be sure not to miss this book.

I managed to miss Marlena when it first came out last year; luckily, I had another chance at reading it when it was released in paperback a couple of months ago. It bears some thematic similarities to Emma Cline’s The Girls, Rosalie Knecht’s Relief Map, Andrée Michaud’s The Last Summer, Julianne Pachico’s The Lucky Ones and especially Emily Fridlund’s History of Wolves, but Marlena is a cut above. It’s basically a flawless debut, one I can’t recommend too highly. Occasionally I weary of writing straightforward reviews – let’s be honest, you get tired of reading them, too – so I’m returning to a format I last used for my review of The Animators and pulling out four reasons why you must be sure not to miss this book.

- Michigan. Have you ever read another book set in northern Michigan? After her parents’ divorce, Cat moves to Silver Lake with her mom and older brother, and almost immediately meets Marlena Joyner, their new next-door neighbor. Although Marlena drowns in suspicious circumstances less than a year later – this is not a spoiler; it is part of the back cover blurb and is also revealed on the fourth page – her impact on Cat will last for decades. The setting pairs perfectly with the novel’s tone of foreboding: you have a sense of these troubled teens being isolated in their clearing in the woods, and from one frigid winter through a steamy summer and into the chill of the impending autumn, they have to figure out what in the world they are going to do with their terrifying freedom.

Probably most teenagers think where they live is boring. But there aren’t words for the catastrophic dreariness of being fifteen in northern Michigan at the tail end of winter, when you haven’t seen the sun in weeks and the snow won’t stop coming and there’s nowhere to go and you’re always cold and everyone you know is broke…

- Emulation and Envy. Catherine wants to be just like 17-year-old Marlena: experienced, sensual and insouciant. She puts childish hobbies and studious habits behind her and remakes herself as “Cat” at her new school. Through Marlena she develops a taste for alcohol and cigarettes. She also turns truant and starts hanging out with drug dealers at all hours. All along she’s conveniently ignoring that Marlena is essentially parentless – her mother left and her father cooks meth – and that popping pills and sleeping around aren’t exactly a great strategy for getting out of Silver Lake. Living with a single mom who works as a cleaner, Cat also starts to envy the rich incomers whose summer houses she helps to clean. In the scene that may well linger with me the longest, Cat tastes whole almonds for the first time at the Hodsons’ mansion and steals a stash.

I looked up to Marlena—she was tough and beautiful and I never once thought she wasn’t in control. … Even at fifteen I wasn’t dumb enough to glamorize Marlena’s world, the poverty, the drugs that were the fabric of everything, but I was attracted to it all the same.

- Teenage Shenanigans. I was the squeakiest of squeaky clean kids in high school, but it’s always fun to experience very different lives through fiction. With Cat and Marlena you’ll get to skip school, throw unsupervised parties, and pull all manner of pranks. Their most impressive spectacle is affixing giant papier-mâché genitalia to a Big Boy restaurant statue as an act of revenge on a teacher who hit on Marlena.

Everything was happening in consequence-less free fall … the two of us made one perfect, unfuckwithable girl. Nothing could hurt us, as long as we weren’t alone.

- Hindsight Is Everything. Cat is writing this nearly 20 years later. In short interludes labeled “New York,” we learn about her adult life: a job in a library, a husband named Liam, and an ongoing struggle with a bad habit she formed under Marlena’s influence. When Marlena’s little brother Sal gets in touch and asks to visit Cat in New York City to hear about the sister he barely remembers, it sparks a trip back into memory. This narrative is like an exorcism or a system detox for Cat: not until she gets it out can she truly live her own life.

Those days were so big and electric that they swallowed the future and the past … a difficulty letting go of the past can run in families, like a problematic thyroid.

This is one of those books where the narration is so utterly convincing that you don’t so much read the plot as live it out. I felt no distance between Cat and me. When a first-person voice is this successful, you wonder why an author would ever choose anything else.

My rating:

Marlena was published in paperback in the UK by Picador on April 19th. My thanks to the publisher for sending a free copy for review.

Setting up a game of solitaire in The Snow Hare by Paula Lichtarowicz and Of Mice and Men by John Steinbeck.

Setting up a game of solitaire in The Snow Hare by Paula Lichtarowicz and Of Mice and Men by John Steinbeck.

The family’s pet chicken is cooked for dinner in Coleman Hill by Kim Coleman Foote and The Snow Hare by Paula Lichtarowicz.

The family’s pet chicken is cooked for dinner in Coleman Hill by Kim Coleman Foote and The Snow Hare by Paula Lichtarowicz.

A large anonymous donation to a church in Slammerkin by Emma Donoghue and Excellent Women by Barbara Pym (£10–11, which was much more in the 18th century of the former than in the 1950s of the latter).

A large anonymous donation to a church in Slammerkin by Emma Donoghue and Excellent Women by Barbara Pym (£10–11, which was much more in the 18th century of the former than in the 1950s of the latter).

A man throws his tie over his shoulder before eating in Recipe for a Perfect Wife by Karma Brown and Keep by Jenny Haysom.

A man throws his tie over his shoulder before eating in Recipe for a Perfect Wife by Karma Brown and Keep by Jenny Haysom. A scene of self-induced abortion in Recipe for a Perfect Wife by Karma Brown and Sleeping with Cats by Marge Piercy.

A scene of self-induced abortion in Recipe for a Perfect Wife by Karma Brown and Sleeping with Cats by Marge Piercy.

Merritt asked about the novel’s magic realist element and how stylistically different his novels have been from each other. He was glad she found the book funny, as “life is tragicomic.” In an effort not to get stuck in a rut, he deliberately ‘breaks the mould’ after each book and starts over. This has not made him popular with his publisher!

Merritt asked about the novel’s magic realist element and how stylistically different his novels have been from each other. He was glad she found the book funny, as “life is tragicomic.” In an effort not to get stuck in a rut, he deliberately ‘breaks the mould’ after each book and starts over. This has not made him popular with his publisher!

Last year’s Dylan Thomas Prize winner interviewed this year’s winner, and it was clear that the mutual admiration was strong. Though I had mixed feelings about Luster (

Last year’s Dylan Thomas Prize winner interviewed this year’s winner, and it was clear that the mutual admiration was strong. Though I had mixed feelings about Luster (

Shipstead (also a Dylan Thomas Prize winner) echoed something Leilani had said: that she starts a novel with questions, not answers. Such humility is refreshing, and a sure way to avoid being preachy in fiction. Her new novel, Great Circle, is among my

Shipstead (also a Dylan Thomas Prize winner) echoed something Leilani had said: that she starts a novel with questions, not answers. Such humility is refreshing, and a sure way to avoid being preachy in fiction. Her new novel, Great Circle, is among my

Lockwood is the only novelist to be included on the Atlantic’s roster of best tweets. She and Nina Stibbe, who interviewed her, agreed that 1) things aren’t funny when they try too hard and 2) the Internet used to be a taboo subject for fiction – producing time-stamped references that editors used to remove. “I had so many observations and I didn’t know where to put them,” Lockwood said, and it seems to her perverse to not write about something that is such a major part of our daily lives. The title of her Women’s Prize-shortlisted novel, No One Is Talking About This (

Lockwood is the only novelist to be included on the Atlantic’s roster of best tweets. She and Nina Stibbe, who interviewed her, agreed that 1) things aren’t funny when they try too hard and 2) the Internet used to be a taboo subject for fiction – producing time-stamped references that editors used to remove. “I had so many observations and I didn’t know where to put them,” Lockwood said, and it seems to her perverse to not write about something that is such a major part of our daily lives. The title of her Women’s Prize-shortlisted novel, No One Is Talking About This (

Like Lockwood, Pachico was part of the “10 @ 10” series featuring debut novelists (though her first book, the linked story collection

Like Lockwood, Pachico was part of the “10 @ 10” series featuring debut novelists (though her first book, the linked story collection

Speaking to Arifa Akbar about

Speaking to Arifa Akbar about

I’ve read more of and gotten on better with Heti’s work than Cusk’s, so this was a rare case of being perhaps more interested in interviewer than interviewee. Heti said that, compared with the Outline trilogy, Cusk’s new novel Second Place feels wilder and more instinctual. Cusk, speaking from the Greek island of Tinos, where she is researching marble quarrying, described her book in often vague yet overall intriguing terms: it’s about exile and the illicit, she said; about femininity and entitlement to speak; about the domestic space and how things are legitimized; about the adoption of male values and the “rightness of the artist.”

I’ve read more of and gotten on better with Heti’s work than Cusk’s, so this was a rare case of being perhaps more interested in interviewer than interviewee. Heti said that, compared with the Outline trilogy, Cusk’s new novel Second Place feels wilder and more instinctual. Cusk, speaking from the Greek island of Tinos, where she is researching marble quarrying, described her book in often vague yet overall intriguing terms: it’s about exile and the illicit, she said; about femininity and entitlement to speak; about the domestic space and how things are legitimized; about the adoption of male values and the “rightness of the artist.”

The Charmed Wife by Olga Grushin [Jan. 21, Hodder & Stoughton / Jan. 12, Putnam] “Cinderella married the man of her dreams – the perfect ending she deserved after diligently following all the fairy-tale rules. Yet now, two children and thirteen-and-a-half years later, things have gone badly wrong. One night, she sneaks out of the palace to get help from the Witch who, for a price, offers love potions to disgruntled housewives.” A feminist retelling. I loved Grushin’s previous novel, Forty Rooms. [Edelweiss download]

The Charmed Wife by Olga Grushin [Jan. 21, Hodder & Stoughton / Jan. 12, Putnam] “Cinderella married the man of her dreams – the perfect ending she deserved after diligently following all the fairy-tale rules. Yet now, two children and thirteen-and-a-half years later, things have gone badly wrong. One night, she sneaks out of the palace to get help from the Witch who, for a price, offers love potions to disgruntled housewives.” A feminist retelling. I loved Grushin’s previous novel, Forty Rooms. [Edelweiss download] The Prophets by Robert Jones Jr. [Jan. 21, Quercus / Jan. 5, G.P. Putnam’s Sons] “A singular and stunning debut novel about the forbidden union between two enslaved young men on a Deep South plantation, the refuge they find in each other, and a betrayal that threatens their existence.” Lots of hype about this one. I’m getting Days Without End vibes, and the mention of copious biblical references is a draw for me rather than a turn-off. The cover looks so much like the UK cover of

The Prophets by Robert Jones Jr. [Jan. 21, Quercus / Jan. 5, G.P. Putnam’s Sons] “A singular and stunning debut novel about the forbidden union between two enslaved young men on a Deep South plantation, the refuge they find in each other, and a betrayal that threatens their existence.” Lots of hype about this one. I’m getting Days Without End vibes, and the mention of copious biblical references is a draw for me rather than a turn-off. The cover looks so much like the UK cover of  Mrs Death Misses Death by Salena Godden [Jan. 28, Canongate] “Mrs Death has had enough. She is exhausted from spending eternity doing her job and now she seeks someone to unburden her conscience to. Wolf Willeford, a troubled young writer, is well acquainted with death, but until now hadn’t met Death in person – a black, working-class woman who shape-shifts and does her work unseen. Enthralled by her stories, Wolf becomes Mrs Death’s scribe, and begins to write her memoirs.” [NetGalley download / Library hold]

Mrs Death Misses Death by Salena Godden [Jan. 28, Canongate] “Mrs Death has had enough. She is exhausted from spending eternity doing her job and now she seeks someone to unburden her conscience to. Wolf Willeford, a troubled young writer, is well acquainted with death, but until now hadn’t met Death in person – a black, working-class woman who shape-shifts and does her work unseen. Enthralled by her stories, Wolf becomes Mrs Death’s scribe, and begins to write her memoirs.” [NetGalley download / Library hold] A Town Called Solace by Mary Lawson [Feb. 18, Chatto & Windus / Feb. 16, Knopf Canada] “It’s North Ontario in 1972, and seven-year-old Clara’s teenage sister Rose has just run away from home. At the same time, a strange man – Liam – drives up to the house next door, which he has just inherited from Mrs Orchard, a kindly old woman who was friendly to Clara … A beautiful portrait of a small town, a little girl and an exploration of childhood.” I’ve loved the two Lawson novels I’ve read. [Publisher request pending]

A Town Called Solace by Mary Lawson [Feb. 18, Chatto & Windus / Feb. 16, Knopf Canada] “It’s North Ontario in 1972, and seven-year-old Clara’s teenage sister Rose has just run away from home. At the same time, a strange man – Liam – drives up to the house next door, which he has just inherited from Mrs Orchard, a kindly old woman who was friendly to Clara … A beautiful portrait of a small town, a little girl and an exploration of childhood.” I’ve loved the two Lawson novels I’ve read. [Publisher request pending] Klara and the Sun by Kazuo Ishiguro [March 2, Faber & Faber / Knopf] Synopsis from Faber e-mail: “Klara and the Sun is the story of an ‘Artificial Friend’ who … is warned not to invest too much in the promises of humans. A luminous narrative about humanity, hope and the human heart.” I’m not an Ishiguro fan per se, but this looks set to be one of the biggest books of the year. I’m tempted to pre-order a signed copy as part of an early bird ticket to a Faber Members live-streamed event with him in early March.

Klara and the Sun by Kazuo Ishiguro [March 2, Faber & Faber / Knopf] Synopsis from Faber e-mail: “Klara and the Sun is the story of an ‘Artificial Friend’ who … is warned not to invest too much in the promises of humans. A luminous narrative about humanity, hope and the human heart.” I’m not an Ishiguro fan per se, but this looks set to be one of the biggest books of the year. I’m tempted to pre-order a signed copy as part of an early bird ticket to a Faber Members live-streamed event with him in early March. Hot Stew by Fiona Mozley [March 18, Hodder & Stoughton / April 20, Algonquin Books] “The Soho that Precious and Tabitha live and work in is barely recognizable anymore. … Billionaire-owner Agatha wants to kick the women out to build expensive restaurants and luxury flats. Men like Robert, who visit the brothel, will have to go elsewhere. … An insightful and ambitious novel about property, ownership, wealth and inheritance.” This sounds very different to

Hot Stew by Fiona Mozley [March 18, Hodder & Stoughton / April 20, Algonquin Books] “The Soho that Precious and Tabitha live and work in is barely recognizable anymore. … Billionaire-owner Agatha wants to kick the women out to build expensive restaurants and luxury flats. Men like Robert, who visit the brothel, will have to go elsewhere. … An insightful and ambitious novel about property, ownership, wealth and inheritance.” This sounds very different to  Libertie by Kaitlyn Greenidge [March 30, Algonquin Books; April 29, Serpent’s Tail] “Coming of age as a free-born Black girl in Reconstruction-era Brooklyn, Libertie Sampson” is expected to follow in her mother’s footsteps as a doctor. “When a young man from Haiti proposes, she accepts, only to discover that she is still subordinate to him and all men. … Inspired by the life of one of the first Black female doctors in the United States.” I loved Greenidge’s underappreciated debut, We Love You, Charlie Freeman. [Edelweiss download]

Libertie by Kaitlyn Greenidge [March 30, Algonquin Books; April 29, Serpent’s Tail] “Coming of age as a free-born Black girl in Reconstruction-era Brooklyn, Libertie Sampson” is expected to follow in her mother’s footsteps as a doctor. “When a young man from Haiti proposes, she accepts, only to discover that she is still subordinate to him and all men. … Inspired by the life of one of the first Black female doctors in the United States.” I loved Greenidge’s underappreciated debut, We Love You, Charlie Freeman. [Edelweiss download] An Ordinary Wonder by Buki Papillon [April 9, Dialogue Books] “Richly imagined with art, proverbs and folk tales, this moving and modern novel follows Oto through life at home and at boarding school in Nigeria, through the heartbreak of living as a boy despite their profound belief they are a girl, and through a hunger for freedom that only a new life in the United States can offer. … a powerful coming-of-age story that explores complex desires as well as challenges of family, identity, gender and culture, and what it means to feel whole.”

An Ordinary Wonder by Buki Papillon [April 9, Dialogue Books] “Richly imagined with art, proverbs and folk tales, this moving and modern novel follows Oto through life at home and at boarding school in Nigeria, through the heartbreak of living as a boy despite their profound belief they are a girl, and through a hunger for freedom that only a new life in the United States can offer. … a powerful coming-of-age story that explores complex desires as well as challenges of family, identity, gender and culture, and what it means to feel whole.” The Anthill by Julianne Pachico [May 6, Faber & Faber; this has been out since May 2020 in the USA, but was pushed back a year in the UK] “Linda returns to Colombia after 20 years away. Sent to England after her mother’s death when she was eight, she’s searching for the person who can tell her what’s happened in the time that has passed. Matty – Lina’s childhood confidant, her best friend – now runs a refuge called The Anthill for the street kids of Medellín.” Pachico was our Young Writer of the Year shadow panel winner.

The Anthill by Julianne Pachico [May 6, Faber & Faber; this has been out since May 2020 in the USA, but was pushed back a year in the UK] “Linda returns to Colombia after 20 years away. Sent to England after her mother’s death when she was eight, she’s searching for the person who can tell her what’s happened in the time that has passed. Matty – Lina’s childhood confidant, her best friend – now runs a refuge called The Anthill for the street kids of Medellín.” Pachico was our Young Writer of the Year shadow panel winner. Filthy Animals: Stories by Brandon Taylor [June 24, Daunt Books / June 21, Riverhead] “In the series of linked stories at the heart of Filthy Animals, set among young creatives in the American Midwest, a young man treads delicate emotional waters as he navigates a series of sexually fraught encounters with two dancers in an open relationship, forcing him to weigh his vulnerabilities against his loneliness.” Sounds like the perfect follow-up for those of us who loved his Booker-shortlisted debut novel,

Filthy Animals: Stories by Brandon Taylor [June 24, Daunt Books / June 21, Riverhead] “In the series of linked stories at the heart of Filthy Animals, set among young creatives in the American Midwest, a young man treads delicate emotional waters as he navigates a series of sexually fraught encounters with two dancers in an open relationship, forcing him to weigh his vulnerabilities against his loneliness.” Sounds like the perfect follow-up for those of us who loved his Booker-shortlisted debut novel,  Islands of Abandonment: Nature Rebounding in the Post-Human Landscape by Cal Flyn [Jan. 21, William Collins; June 1, Viking] “A variety of wildlife not seen in many lifetimes has rebounded on the irradiated grounds of Chernobyl. A lush forest supports thousands of species that are extinct or endangered everywhere else on earth in the Korean peninsula’s narrow DMZ. … Islands of Abandonment is a tour through these new ecosystems … ultimately a story of redemption”. Good news about nature is always nice to find. [Publisher request pending]

Islands of Abandonment: Nature Rebounding in the Post-Human Landscape by Cal Flyn [Jan. 21, William Collins; June 1, Viking] “A variety of wildlife not seen in many lifetimes has rebounded on the irradiated grounds of Chernobyl. A lush forest supports thousands of species that are extinct or endangered everywhere else on earth in the Korean peninsula’s narrow DMZ. … Islands of Abandonment is a tour through these new ecosystems … ultimately a story of redemption”. Good news about nature is always nice to find. [Publisher request pending] The Believer by Sarah Krasnostein [March 2, Text Publishing – might be Australia only; I’ll have an eagle eye out for news of a UK release] “This book is about ghosts and gods and flying saucers; certainty in the absence of knowledge; how the stories we tell ourselves to deal with the distance between the world as it is and as we’d like it to be can stunt us or save us.” Krasnostein was our Wellcome Book Prize shadow panel winner in 2019. She told us a bit about this work in progress at the prize ceremony and I was intrigued!

The Believer by Sarah Krasnostein [March 2, Text Publishing – might be Australia only; I’ll have an eagle eye out for news of a UK release] “This book is about ghosts and gods and flying saucers; certainty in the absence of knowledge; how the stories we tell ourselves to deal with the distance between the world as it is and as we’d like it to be can stunt us or save us.” Krasnostein was our Wellcome Book Prize shadow panel winner in 2019. She told us a bit about this work in progress at the prize ceremony and I was intrigued! A History of Scars: A Memoir by Laura Lee [March 2, Atria Books; no sign of a UK release] “In this stunning debut, Laura Lee weaves unforgettable and eye-opening essays on a variety of taboo topics. … Through the vivid imagery of mountain climbing, cooking, studying writing, and growing up Korean American, Lee explores the legacy of trauma on a young queer child of immigrants as she reconciles the disparate pieces of existence that make her whole.” I was drawn to this one by Roxane Gay’s high praise.

A History of Scars: A Memoir by Laura Lee [March 2, Atria Books; no sign of a UK release] “In this stunning debut, Laura Lee weaves unforgettable and eye-opening essays on a variety of taboo topics. … Through the vivid imagery of mountain climbing, cooking, studying writing, and growing up Korean American, Lee explores the legacy of trauma on a young queer child of immigrants as she reconciles the disparate pieces of existence that make her whole.” I was drawn to this one by Roxane Gay’s high praise. Everybody: A Book about Freedom by Olivia Laing [April 29, Picador / May 4, W. W. Norton & Co.] “The body is a source of pleasure and of pain, at once hopelessly vulnerable and radiant with power. … Laing charts an electrifying course through the long struggle for bodily freedom, using the life of the renegade psychoanalyst Wilhelm Reich to explore gay rights and sexual liberation, feminism, and the civil rights movement.” Wellcome Prize fodder from the author of

Everybody: A Book about Freedom by Olivia Laing [April 29, Picador / May 4, W. W. Norton & Co.] “The body is a source of pleasure and of pain, at once hopelessly vulnerable and radiant with power. … Laing charts an electrifying course through the long struggle for bodily freedom, using the life of the renegade psychoanalyst Wilhelm Reich to explore gay rights and sexual liberation, feminism, and the civil rights movement.” Wellcome Prize fodder from the author of  Rooted: Life at the Crossroads of Science, Nature, and Spirit by Lyanda Lynn Haupt [May 4, Little, Brown Spark; no sign of a UK release] “Cutting-edge science supports a truth that poets, artists, mystics, and earth-based cultures across the world have proclaimed over millennia: life on this planet is radically interconnected. … In the tradition of Rachel Carson, Elizabeth Kolbert, and Mary Oliver, Haupt writes with urgency and grace, reminding us that at the crossroads of science, nature, and spirit we find true hope.” I’m a Haupt fan.

Rooted: Life at the Crossroads of Science, Nature, and Spirit by Lyanda Lynn Haupt [May 4, Little, Brown Spark; no sign of a UK release] “Cutting-edge science supports a truth that poets, artists, mystics, and earth-based cultures across the world have proclaimed over millennia: life on this planet is radically interconnected. … In the tradition of Rachel Carson, Elizabeth Kolbert, and Mary Oliver, Haupt writes with urgency and grace, reminding us that at the crossroads of science, nature, and spirit we find true hope.” I’m a Haupt fan.

Piranesi by Susanna Clarke [Sept. 15, Bloomsbury] “Piranesi’s house is no ordinary building: its rooms are infinite, its corridors endless. … For readers of Neil Gaiman’s The Ocean at the End of the Lane … Piranesi introduces an astonishing new world.” It feels like forever since we had a book from Clarke. I remember devouring Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell during a boating holiday on the Norfolk Broads in 2006. But whew: this one is only 272 pages.

Piranesi by Susanna Clarke [Sept. 15, Bloomsbury] “Piranesi’s house is no ordinary building: its rooms are infinite, its corridors endless. … For readers of Neil Gaiman’s The Ocean at the End of the Lane … Piranesi introduces an astonishing new world.” It feels like forever since we had a book from Clarke. I remember devouring Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell during a boating holiday on the Norfolk Broads in 2006. But whew: this one is only 272 pages. The Swallowed Man by Edward Carey [Nov. 5, Gallic / Oct. 27, Riverhead] “A beautiful and haunting imagining of the years Geppetto spends within the belly of a sea beast. Drawing upon the Pinocchio story while creating something entirely his own, Carey tells an unforgettable tale of fatherly love and loss, pride and regret, and of the sustaining power of art and imagination.” His

The Swallowed Man by Edward Carey [Nov. 5, Gallic / Oct. 27, Riverhead] “A beautiful and haunting imagining of the years Geppetto spends within the belly of a sea beast. Drawing upon the Pinocchio story while creating something entirely his own, Carey tells an unforgettable tale of fatherly love and loss, pride and regret, and of the sustaining power of art and imagination.” His

Dearly: New Poems by Margaret Atwood [Nov. 10, Chatto & Windus / Ecco / McClelland & Stewart] “By turns moving, playful and wise, the poems … are about absences and endings, ageing and retrospection, but also about gifts and renewals. They explore bodies and minds in transition … Werewolves, sirens and dreams make their appearance, as do various forms of animal life and fragments of our damaged environment.”

Dearly: New Poems by Margaret Atwood [Nov. 10, Chatto & Windus / Ecco / McClelland & Stewart] “By turns moving, playful and wise, the poems … are about absences and endings, ageing and retrospection, but also about gifts and renewals. They explore bodies and minds in transition … Werewolves, sirens and dreams make their appearance, as do various forms of animal life and fragments of our damaged environment.” Bright Precious Thing: A Memoir by Gail Caldwell [July 7, Random House] “In a voice as candid as it is evocative, Gail Caldwell traces a path from her west Texas girlhood through her emergence as a young daredevil, then as a feminist.” I’ve enjoyed two of Caldwell’s previous books, especially

Bright Precious Thing: A Memoir by Gail Caldwell [July 7, Random House] “In a voice as candid as it is evocative, Gail Caldwell traces a path from her west Texas girlhood through her emergence as a young daredevil, then as a feminist.” I’ve enjoyed two of Caldwell’s previous books, especially  The Fragments of My Father by Sam Mills [July 9, Fourth Estate] A memoir of being the primary caregiver for her father, who had schizophrenia; with references to F. Scott Fitzgerald and Leonard Woolf, who also found themselves caring for people struggling with mental illness. “A powerful and poignant memoir about parents and children, freedom and responsibility, madness and creativity and what it means to be a carer.”

The Fragments of My Father by Sam Mills [July 9, Fourth Estate] A memoir of being the primary caregiver for her father, who had schizophrenia; with references to F. Scott Fitzgerald and Leonard Woolf, who also found themselves caring for people struggling with mental illness. “A powerful and poignant memoir about parents and children, freedom and responsibility, madness and creativity and what it means to be a carer.” Avoid the Day: A New Nonfiction in Two Movements by Jay Kirk [July 28, Harper Perennial] Transylvania, Béla Bartók’s folk songs, an eco-tourist cruise in the Arctic … “Avoid the Day is part detective story, part memoir, and part meditation on the meaning of life—all told with a dark pulse of existential horror.” It was Helen Macdonald’s testimonial that drew me to this: it “truly seems to me to push nonfiction memoir as far as it can go.”

Avoid the Day: A New Nonfiction in Two Movements by Jay Kirk [July 28, Harper Perennial] Transylvania, Béla Bartók’s folk songs, an eco-tourist cruise in the Arctic … “Avoid the Day is part detective story, part memoir, and part meditation on the meaning of life—all told with a dark pulse of existential horror.” It was Helen Macdonald’s testimonial that drew me to this: it “truly seems to me to push nonfiction memoir as far as it can go.” World of Wonders: In Praise of Fireflies, Whale Sharks, and Other Astonishments by Aimee Nezhukumatathil [Aug. 3, Milkweed Editions] “From beloved, award-winning poet Aimee Nezhukumatathil comes a debut work of nonfiction—a collection of essays about the natural world, and the way its inhabitants can teach, support, and inspire us. … Even in the strange and the unlovely, Nezhukumatathil finds beauty and kinship.” Who could resist that title or cover?

World of Wonders: In Praise of Fireflies, Whale Sharks, and Other Astonishments by Aimee Nezhukumatathil [Aug. 3, Milkweed Editions] “From beloved, award-winning poet Aimee Nezhukumatathil comes a debut work of nonfiction—a collection of essays about the natural world, and the way its inhabitants can teach, support, and inspire us. … Even in the strange and the unlovely, Nezhukumatathil finds beauty and kinship.” Who could resist that title or cover? Antlers of Water: Writing on the Nature and Environment of Scotland, edited by Kathleen Jamie [Aug. 6, Canongate] Contributors include Amy Liptrot, musician Karine Polwart and Malachy Tallack. “Featuring prose, poetry and photography, this inspiring collection takes us from walking to wild swimming, from red deer to pigeons and wasps, from remote islands to back gardens … writing which is by turns celebratory, radical and political.”

Antlers of Water: Writing on the Nature and Environment of Scotland, edited by Kathleen Jamie [Aug. 6, Canongate] Contributors include Amy Liptrot, musician Karine Polwart and Malachy Tallack. “Featuring prose, poetry and photography, this inspiring collection takes us from walking to wild swimming, from red deer to pigeons and wasps, from remote islands to back gardens … writing which is by turns celebratory, radical and political.” The Good Ancestor: How to Think Long Term in a Short-Term World by Roman Krznaric [Aug. 27, W.H. Allen] “Drawing on radical solutions from around the world, Krznaric celebrates the innovators who are reinventing democracy, culture and economics so that we all have the chance to become good ancestors and create a better tomorrow.” I’ve been reading a fair bit around this topic. I got a sneak preview of this one from

The Good Ancestor: How to Think Long Term in a Short-Term World by Roman Krznaric [Aug. 27, W.H. Allen] “Drawing on radical solutions from around the world, Krznaric celebrates the innovators who are reinventing democracy, culture and economics so that we all have the chance to become good ancestors and create a better tomorrow.” I’ve been reading a fair bit around this topic. I got a sneak preview of this one from  Eat the Buddha: The Story of Modern Tibet through the People of One Town by Barbara Demick [Sept. 3, Granta / July 28, Random House] “Illuminating a culture that has long been romanticized by Westerners as deeply spiritual and peaceful, Demick reveals what it is really like to be a Tibetan in the twenty-first century, trying to preserve one’s culture, faith, and language.” I read her book on North Korea and found it eye-opening. I’ve read a few books about Tibet over the years; it is fascinating.

Eat the Buddha: The Story of Modern Tibet through the People of One Town by Barbara Demick [Sept. 3, Granta / July 28, Random House] “Illuminating a culture that has long been romanticized by Westerners as deeply spiritual and peaceful, Demick reveals what it is really like to be a Tibetan in the twenty-first century, trying to preserve one’s culture, faith, and language.” I read her book on North Korea and found it eye-opening. I’ve read a few books about Tibet over the years; it is fascinating. Entangled Life: How Fungi Make Our Worlds, Change Our Minds and Shape Our Futures by Merlin Sheldrake [Sept. 3, Bodley Head / May 12, Random House] “Entangled Life is a mind-altering journey into this hidden kingdom of life, and shows that fungi are key to understanding the planet on which we live, and the ways we think, feel and behave.” I like spotting fungi. Yes, yes, the title and cover are amazing, but also the author’s name!! – how could you not want to read this?

Entangled Life: How Fungi Make Our Worlds, Change Our Minds and Shape Our Futures by Merlin Sheldrake [Sept. 3, Bodley Head / May 12, Random House] “Entangled Life is a mind-altering journey into this hidden kingdom of life, and shows that fungi are key to understanding the planet on which we live, and the ways we think, feel and behave.” I like spotting fungi. Yes, yes, the title and cover are amazing, but also the author’s name!! – how could you not want to read this? Between Light and Storm: How We Live with Other Species by Esther Woolfson [Sept. 3, Granta] “Woolfson considers prehistoric human‒animal interaction and traces the millennia-long evolution of conceptions of the soul and conscience in relation to the animal kingdom, and the consequences of our belief in human superiority.” I’ve read two previous nature books by Woolfson and have done some recent reading around deep time concepts. This is sure to be a thoughtful and nuanced take.

Between Light and Storm: How We Live with Other Species by Esther Woolfson [Sept. 3, Granta] “Woolfson considers prehistoric human‒animal interaction and traces the millennia-long evolution of conceptions of the soul and conscience in relation to the animal kingdom, and the consequences of our belief in human superiority.” I’ve read two previous nature books by Woolfson and have done some recent reading around deep time concepts. This is sure to be a thoughtful and nuanced take. The Stubborn Light of Things: A Nature Diary by Melissa Harrison [Nov. 5, Faber & Faber] “Moving from scrappy city verges to ancient, rural Suffolk, where Harrison eventually relocates, this diary—compiled from her beloved “Nature Notebook” column in The Times—maps her joyful engagement with the natural world and demonstrates how we must first learn to see, and then act to preserve, the beauty we have on our doorsteps.” I love seeing her nature finds on Twitter. I think her writing will suit this format.

The Stubborn Light of Things: A Nature Diary by Melissa Harrison [Nov. 5, Faber & Faber] “Moving from scrappy city verges to ancient, rural Suffolk, where Harrison eventually relocates, this diary—compiled from her beloved “Nature Notebook” column in The Times—maps her joyful engagement with the natural world and demonstrates how we must first learn to see, and then act to preserve, the beauty we have on our doorsteps.” I love seeing her nature finds on Twitter. I think her writing will suit this format.

Midwinter Break by Bernard MacLaverty: In MacLaverty’s quietly beautiful fifth novel, a retired couple faces up to past trauma and present incompatibility during a short vacation in Amsterdam. My overall response was one of admiration for what this couple has survived and sympathy for their current situation – with hope that they’ll make it through this, too. (Reviewed for

Midwinter Break by Bernard MacLaverty: In MacLaverty’s quietly beautiful fifth novel, a retired couple faces up to past trauma and present incompatibility during a short vacation in Amsterdam. My overall response was one of admiration for what this couple has survived and sympathy for their current situation – with hope that they’ll make it through this, too. (Reviewed for

Lincoln in the Bardo by George Saunders: The residents of Georgetown cemetery limbo don’t know they’re dead – or at least won’t accept it. An entertaining and truly original treatment of life’s transience; I know it’s on every other best-of-year list out there, but it really is a must-read.

Lincoln in the Bardo by George Saunders: The residents of Georgetown cemetery limbo don’t know they’re dead – or at least won’t accept it. An entertaining and truly original treatment of life’s transience; I know it’s on every other best-of-year list out there, but it really is a must-read.

A Life of My Own by Claire Tomalin: Tomalin is best known as a biographer of literary figures including Mary Wollstonecraft, Samuel Pepys and Charles Dickens, but her memoir is especially revealing about the social and cultural history of the earlier decades her life covers. A dignified but slightly aloof book – well worth reading for anyone interested in spending time in London’s world of letters in the second half of the twentieth century.

A Life of My Own by Claire Tomalin: Tomalin is best known as a biographer of literary figures including Mary Wollstonecraft, Samuel Pepys and Charles Dickens, but her memoir is especially revealing about the social and cultural history of the earlier decades her life covers. A dignified but slightly aloof book – well worth reading for anyone interested in spending time in London’s world of letters in the second half of the twentieth century. Sing, Unburied, Sing by Jesmyn Ward: The story of a mixed-race family haunted – both literally and figuratively – by the effects of racism, drug abuse and incarceration in Bois Sauvage, a fictional Mississippi town. Beautiful language; perfect for fans of Toni Morrison and Cynthia Bond.

Sing, Unburied, Sing by Jesmyn Ward: The story of a mixed-race family haunted – both literally and figuratively – by the effects of racism, drug abuse and incarceration in Bois Sauvage, a fictional Mississippi town. Beautiful language; perfect for fans of Toni Morrison and Cynthia Bond. What It Means when a Man Falls from the Sky by Lesley Nneka Arimah (Reviewed for

What It Means when a Man Falls from the Sky by Lesley Nneka Arimah (Reviewed for  The Education of a Coroner by John Bateson: The coroner’s career is eventful no matter what, but Marin County, California has its fair share of special interest, what with Golden Gate Bridge suicides, misdeeds at San Quentin Prison, and various cases involving celebrities (e.g. Harvey Milk, Jerry Garcia and Tupac) in addition to your everyday sordid homicides. Ken Holmes was a death investigator and coroner in Marin County for 36 years; Bateson successfully recreates Holmes’ cases with plenty of (sometimes gory) details.

The Education of a Coroner by John Bateson: The coroner’s career is eventful no matter what, but Marin County, California has its fair share of special interest, what with Golden Gate Bridge suicides, misdeeds at San Quentin Prison, and various cases involving celebrities (e.g. Harvey Milk, Jerry Garcia and Tupac) in addition to your everyday sordid homicides. Ken Holmes was a death investigator and coroner in Marin County for 36 years; Bateson successfully recreates Holmes’ cases with plenty of (sometimes gory) details. Cork Dork by Bianca Bosker: Tasting notes: gleeful, ebullient, learned, self-deprecating; suggested pairings: Sweetbitter by Stephanie Danler; Top Chef, The Great British Bake Off. A delightful blend of science, memoir and encounters with people who are deadly serious about wine.

Cork Dork by Bianca Bosker: Tasting notes: gleeful, ebullient, learned, self-deprecating; suggested pairings: Sweetbitter by Stephanie Danler; Top Chef, The Great British Bake Off. A delightful blend of science, memoir and encounters with people who are deadly serious about wine. A Paris All Your Own: Bestselling Women Writers on the City of Light, edited by Eleanor Brown: A highly enjoyable set of 18 autobiographical essays that celebrate what’s wonderful about the place but also acknowledge disillusionment; highlights are from Maggie Shipstead, Paula McLain, Therese Anne Fowler, Jennifer Coburn, Julie Powell and Michelle Gable. If you have a special love for Paris, have always wanted to visit, or just enjoy armchair traveling, this collection won’t disappoint you.

A Paris All Your Own: Bestselling Women Writers on the City of Light, edited by Eleanor Brown: A highly enjoyable set of 18 autobiographical essays that celebrate what’s wonderful about the place but also acknowledge disillusionment; highlights are from Maggie Shipstead, Paula McLain, Therese Anne Fowler, Jennifer Coburn, Julie Powell and Michelle Gable. If you have a special love for Paris, have always wanted to visit, or just enjoy armchair traveling, this collection won’t disappoint you. Ashland & Vine by John Burnside: Essentially, it’s about the American story, individual American stories, and how these are constructed out of the chaos and violence of the past – all filtered through a random friendship that forms between a film student and an older woman in the Midwest. This captivated me from the first page.

Ashland & Vine by John Burnside: Essentially, it’s about the American story, individual American stories, and how these are constructed out of the chaos and violence of the past – all filtered through a random friendship that forms between a film student and an older woman in the Midwest. This captivated me from the first page. Tragic Shores: A Memoir of Dark Travel, Thomas H. Cook: In 28 non-chronological chapters, Cook documents journeys he’s made to places associated with war, massacres, doomed lovers, suicides and other evidence of human suffering. This is by no means your average travel book and it won’t suit those who seek high adventure and/or tropical escapism; instead, it’s a meditative and often melancholy picture of humanity at its best and worst. (Reviewed for

Tragic Shores: A Memoir of Dark Travel, Thomas H. Cook: In 28 non-chronological chapters, Cook documents journeys he’s made to places associated with war, massacres, doomed lovers, suicides and other evidence of human suffering. This is by no means your average travel book and it won’t suit those who seek high adventure and/or tropical escapism; instead, it’s a meditative and often melancholy picture of humanity at its best and worst. (Reviewed for  The Valentine House by Emma Henderson: This is a highly enjoyable family saga set mostly between 1914 and 1976 at an English clan’s summer chalet in the French Alps near Geneva, with events seen from the perspective of a local servant girl. You can really imagine yourself into all the mountain scenes and the book moves quickly –a great one to take on vacation.

The Valentine House by Emma Henderson: This is a highly enjoyable family saga set mostly between 1914 and 1976 at an English clan’s summer chalet in the French Alps near Geneva, with events seen from the perspective of a local servant girl. You can really imagine yourself into all the mountain scenes and the book moves quickly –a great one to take on vacation.

The 2017 Book Everybody Else Loved but I Didn’t: Eleanor Oliphant Is Completely Fine by Gail Honeyman. (See

The 2017 Book Everybody Else Loved but I Didn’t: Eleanor Oliphant Is Completely Fine by Gail Honeyman. (See  The Downright Strangest Book I Read This Year: An English Guide to Birdwatching by Nicholas Royle.

The Downright Strangest Book I Read This Year: An English Guide to Birdwatching by Nicholas Royle. The Best First Line of the Year: “History has failed us, but no matter.” (Pachinko, Min Jin Lee)

The Best First Line of the Year: “History has failed us, but no matter.” (Pachinko, Min Jin Lee)