The Best Books of 2019: Some Runners-Up

I sometimes like to call this post “The Best Books You’ve Probably Never Heard Of (Unless You Heard about Them from Me)”. However, these picks vary quite a bit in terms of how hyped or obscure they are; the ones marked with an asterisk are the ones I consider my hidden gems of the year. Between this post and my Fiction/Poetry and Nonfiction best-of lists, I’ve now highlighted about the top 13% of my year’s reading.

Fiction:

Salt Slow by Julia Armfield: Nine short stories steeped in myth and magic. The body is a site of transformation, or a source of grotesque relics. Armfield’s prose is punchy, with invented verbs and condensed descriptions that just plain work. She was the Young Writer of the Year Award shadow panel winner. I’ll be following her career with interest.

Salt Slow by Julia Armfield: Nine short stories steeped in myth and magic. The body is a site of transformation, or a source of grotesque relics. Armfield’s prose is punchy, with invented verbs and condensed descriptions that just plain work. She was the Young Writer of the Year Award shadow panel winner. I’ll be following her career with interest.

*Agatha by Anne Cathrine Bomann: In late-1940s Paris, a psychiatrist counts down the days and appointments until his retirement. A few experiences awaken him from his apathy, including meeting Agatha, a new German patient with a history of self-harm. This debut novel is a touching, subtle and gently funny story of rediscovering one’s purpose late in life.

*Agatha by Anne Cathrine Bomann: In late-1940s Paris, a psychiatrist counts down the days and appointments until his retirement. A few experiences awaken him from his apathy, including meeting Agatha, a new German patient with a history of self-harm. This debut novel is a touching, subtle and gently funny story of rediscovering one’s purpose late in life.

A Single Thread by Tracy Chevalier: Chevalier is an American expat like me, but she’s lived in England long enough to make this very English novel convincing and full of charm. Violet Speedwell, 38, is an appealing heroine who has to fight for a life of her own in the 1930s. Who knew the hobbies of embroidering kneelers and ringing church bells could be so fascinating?

A Single Thread by Tracy Chevalier: Chevalier is an American expat like me, but she’s lived in England long enough to make this very English novel convincing and full of charm. Violet Speedwell, 38, is an appealing heroine who has to fight for a life of her own in the 1930s. Who knew the hobbies of embroidering kneelers and ringing church bells could be so fascinating?

Akin by Emma Donoghue: An 80-year-old ends up taking his sullen pre-teen great-nephew with him on a long-awaited trip back to his birthplace of Nice, France. The odd-couple dynamic works perfectly and makes for many amusing culture/generation clashes. Donoghue nails it: sharp, true-to-life and never sappy, with spot-on dialogue and vivid scenes.

Akin by Emma Donoghue: An 80-year-old ends up taking his sullen pre-teen great-nephew with him on a long-awaited trip back to his birthplace of Nice, France. The odd-couple dynamic works perfectly and makes for many amusing culture/generation clashes. Donoghue nails it: sharp, true-to-life and never sappy, with spot-on dialogue and vivid scenes.

Things in Jars by Jess Kidd: In 1863 Bridie Devine, female detective extraordinaire, is tasked with finding the six-year-old daughter of a baronet. Kidd paints a convincingly stark picture of Dickensian London, focusing on an underworld of criminals and circus freaks. The prose is spry and amusing, particularly in her compact descriptions of people.

Things in Jars by Jess Kidd: In 1863 Bridie Devine, female detective extraordinaire, is tasked with finding the six-year-old daughter of a baronet. Kidd paints a convincingly stark picture of Dickensian London, focusing on an underworld of criminals and circus freaks. The prose is spry and amusing, particularly in her compact descriptions of people.

*The Unpassing by Chia-Chia Lin: Bleak yet beautiful in the vein of David Vann’s work: the story of a Taiwanese immigrant family in Alaska and the bad luck and poor choices that nearly destroy them. This debut novel is full of atmosphere and the lowering forces of weather and fate.

*The Unpassing by Chia-Chia Lin: Bleak yet beautiful in the vein of David Vann’s work: the story of a Taiwanese immigrant family in Alaska and the bad luck and poor choices that nearly destroy them. This debut novel is full of atmosphere and the lowering forces of weather and fate.

The Doll Factory by Elizabeth Macneal: Set in the early 1850s and focusing on the Great Exhibition and Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, this reveals the everyday world of poor Londoners. It’s a sumptuous and believable fictional world, with touches of gritty realism. A terrific debut full of panache and promise.

The Doll Factory by Elizabeth Macneal: Set in the early 1850s and focusing on the Great Exhibition and Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, this reveals the everyday world of poor Londoners. It’s a sumptuous and believable fictional world, with touches of gritty realism. A terrific debut full of panache and promise.

*The Heavens by Sandra Newman: Not a genre I would normally be drawn to (time travel), yet I found it entrancing. In her dreams Kate becomes Shakespeare’s “Dark Lady” and sees visions of a future burned city. The more she exclaims over changes in her modern-day life, the more people question her mental health. Impressive for how much it packs into 250 pages; something like a cross between Jonathan Franzen and Samantha Harvey.

*The Heavens by Sandra Newman: Not a genre I would normally be drawn to (time travel), yet I found it entrancing. In her dreams Kate becomes Shakespeare’s “Dark Lady” and sees visions of a future burned city. The more she exclaims over changes in her modern-day life, the more people question her mental health. Impressive for how much it packs into 250 pages; something like a cross between Jonathan Franzen and Samantha Harvey.

*In Love with George Eliot by Kathy O’Shaughnessy: Many characters, fictional and historical, are in love with George Eliot over the course of this debut novel. We get intriguing vignettes from Eliot’s life with her two great loves, and insight into her scandalous position in Victorian society. O’Shaughnessy mimics Victorian prose ably.

*In Love with George Eliot by Kathy O’Shaughnessy: Many characters, fictional and historical, are in love with George Eliot over the course of this debut novel. We get intriguing vignettes from Eliot’s life with her two great loves, and insight into her scandalous position in Victorian society. O’Shaughnessy mimics Victorian prose ably.

Daisy Jones and The Six by Taylor Jenkins Reid: This story of the rise and fall of a Fleetwood Mac-esque band is full of verve and heart. It’s so clever how Reid delivers it all as an oral history of pieced-together interview fragments. Pure California sex, drugs, and rock ’n roll, yet there’s nothing clichéd about it.

Daisy Jones and The Six by Taylor Jenkins Reid: This story of the rise and fall of a Fleetwood Mac-esque band is full of verve and heart. It’s so clever how Reid delivers it all as an oral history of pieced-together interview fragments. Pure California sex, drugs, and rock ’n roll, yet there’s nothing clichéd about it.

Graphic Novels:

*ABC of Typography by David Rault: From cuneiform to Comic Sans, this history of typography is delightful. Graphic designer David Rault wrote the whole thing, but each chapter has a different illustrator, so the book is like a taster course in comics styles. It is fascinating to explore the technical characteristics and aesthetic associations of various fonts.

*ABC of Typography by David Rault: From cuneiform to Comic Sans, this history of typography is delightful. Graphic designer David Rault wrote the whole thing, but each chapter has a different illustrator, so the book is like a taster course in comics styles. It is fascinating to explore the technical characteristics and aesthetic associations of various fonts.

*The Lady Doctor by Ian Williams: Dr. Lois Pritchard works at a medical practice in small-town Wales and treats embarrassing ailments at a local genitourinary medicine clinic. The tone is wonderfully balanced: there are plenty of hilarious, somewhat raunchy scenes, but also a lot of heartfelt moments. The drawing style recalls Alison Bechdel’s.

*The Lady Doctor by Ian Williams: Dr. Lois Pritchard works at a medical practice in small-town Wales and treats embarrassing ailments at a local genitourinary medicine clinic. The tone is wonderfully balanced: there are plenty of hilarious, somewhat raunchy scenes, but also a lot of heartfelt moments. The drawing style recalls Alison Bechdel’s.

Poetry:

*Thousandfold by Nina Bogin: This is a lovely collection whose poems devote equal time to interactions with nature and encounters with friends and family. Birds are a frequent presence. Elsewhere Bogin greets a new granddaughter and gives thanks for the comforting presence of her cat. Gentle rhymes and half-rhymes lend a playful or incantatory nature.

*Thousandfold by Nina Bogin: This is a lovely collection whose poems devote equal time to interactions with nature and encounters with friends and family. Birds are a frequent presence. Elsewhere Bogin greets a new granddaughter and gives thanks for the comforting presence of her cat. Gentle rhymes and half-rhymes lend a playful or incantatory nature.

Nonfiction:

*When Death Takes Something from You Give It Back by Naja Marie Aidt: Aidt’s son Carl Emil died in 2015, having jumped out of his fifth-floor Copenhagen window during a mushroom-induced psychosis. The text is a collage of fragments. A playful disregard for chronology and a variety of fonts, typefaces and sizes are ways of circumventing the feeling that grief has made words lose their meaning forever.

*When Death Takes Something from You Give It Back by Naja Marie Aidt: Aidt’s son Carl Emil died in 2015, having jumped out of his fifth-floor Copenhagen window during a mushroom-induced psychosis. The text is a collage of fragments. A playful disregard for chronology and a variety of fonts, typefaces and sizes are ways of circumventing the feeling that grief has made words lose their meaning forever.

*Homesick: Why I Live in a Shed by Catrina Davies: Penniless during an ongoing housing crisis, Davies moved into the shed near Land’s End that had served as her father’s architecture office until he went bankrupt. Like Raynor Winn’s The Salt Path, this intimate, engaging memoir serves as a sobering reminder that homelessness is not so remote.

*Homesick: Why I Live in a Shed by Catrina Davies: Penniless during an ongoing housing crisis, Davies moved into the shed near Land’s End that had served as her father’s architecture office until he went bankrupt. Like Raynor Winn’s The Salt Path, this intimate, engaging memoir serves as a sobering reminder that homelessness is not so remote.

*Hard Pushed: A Midwife’s Story by Leah Hazard: An empathetic picture of patients’ plights and medical professionals’ burnout. Visceral details of sights, smells and feelings put you right there in the delivery room. This is a heartfelt read as well as a vivid and pacey one, and it’s alternately funny and sobering.

*Hard Pushed: A Midwife’s Story by Leah Hazard: An empathetic picture of patients’ plights and medical professionals’ burnout. Visceral details of sights, smells and feelings put you right there in the delivery room. This is a heartfelt read as well as a vivid and pacey one, and it’s alternately funny and sobering.

*Deep Creek: Finding Hope in the High Country by Pam Houston: Autobiographical essays full of the love of place, chiefly her Colorado ranch – a haven in a nomadic career, and a stand-in for the loving family home she never had. It’s about making your own way, and loving the world even – or especially – when it’s threatened with destruction. Highly recommended to readers of The Chronology of Water by Lidia Yuknavitch.

*Deep Creek: Finding Hope in the High Country by Pam Houston: Autobiographical essays full of the love of place, chiefly her Colorado ranch – a haven in a nomadic career, and a stand-in for the loving family home she never had. It’s about making your own way, and loving the world even – or especially – when it’s threatened with destruction. Highly recommended to readers of The Chronology of Water by Lidia Yuknavitch.

*Dancing with Bees: A Journey back to Nature by Brigit Strawbridge Howard: Bees were the author’s gateway into a general appreciation of nature, something she lost for a time in midlife because of the rat race and family complications. She clearly delights in discovery and is devoted to lifelong learning. It’s a book characterized by curiosity and warmth. I ordered signed copies of this and the Simmons (below) directly from the authors via Twitter.

*Dancing with Bees: A Journey back to Nature by Brigit Strawbridge Howard: Bees were the author’s gateway into a general appreciation of nature, something she lost for a time in midlife because of the rat race and family complications. She clearly delights in discovery and is devoted to lifelong learning. It’s a book characterized by curiosity and warmth. I ordered signed copies of this and the Simmons (below) directly from the authors via Twitter.

*Mudlarking: Lost and Found on the River Thames by Lara Maiklem: Maiklem is a London mudlark, scavenging for what washes up on the shores of the Thames, including clay pipes, coins, armaments, pottery, and much more. A fascinating way of bringing history to life and imagining what everyday existence was like for Londoners across the centuries.

*Mudlarking: Lost and Found on the River Thames by Lara Maiklem: Maiklem is a London mudlark, scavenging for what washes up on the shores of the Thames, including clay pipes, coins, armaments, pottery, and much more. A fascinating way of bringing history to life and imagining what everyday existence was like for Londoners across the centuries.

Unfollow: A Journey from Hatred to Hope, Leaving the Westboro Baptist Church by Megan Phelps-Roper: Phelps-Roper grew up in a church founded by her grandfather and made up mostly of her extended family. Its anti-homosexuality message and picketing of military funerals became trademarks. This is an absorbing account of doubt and making a new life outside the only framework you’ve ever known.

Unfollow: A Journey from Hatred to Hope, Leaving the Westboro Baptist Church by Megan Phelps-Roper: Phelps-Roper grew up in a church founded by her grandfather and made up mostly of her extended family. Its anti-homosexuality message and picketing of military funerals became trademarks. This is an absorbing account of doubt and making a new life outside the only framework you’ve ever known.

*A Half Baked Idea: How Grief, Love and Cake Took Me from the Courtroom to Le Cordon Bleu by Olivia Potts: Bereavement memoir + foodie memoir = a perfect book for me. Potts left one very interesting career for another. Losing her mother when she was 25 and meeting her future husband, Sam, who put time and care into cooking, were the immediate spurs to trade in her wig and gown for a chef’s apron.

*A Half Baked Idea: How Grief, Love and Cake Took Me from the Courtroom to Le Cordon Bleu by Olivia Potts: Bereavement memoir + foodie memoir = a perfect book for me. Potts left one very interesting career for another. Losing her mother when she was 25 and meeting her future husband, Sam, who put time and care into cooking, were the immediate spurs to trade in her wig and gown for a chef’s apron.

*The Lost Properties of Love by Sophie Ratcliffe: Not your average memoir. It’s based around train journeys – real and fictional, remembered and imagined; appropriate symbols for many of the book’s dichotomies: scheduling versus unpredictability, having or lacking a direction in life, monotony versus momentous events, and fleeting versus lasting connections.

*The Lost Properties of Love by Sophie Ratcliffe: Not your average memoir. It’s based around train journeys – real and fictional, remembered and imagined; appropriate symbols for many of the book’s dichotomies: scheduling versus unpredictability, having or lacking a direction in life, monotony versus momentous events, and fleeting versus lasting connections.

Inheritance: A Memoir of Genealogy, Paternity, and Love by Dani Shapiro: On a whim, in her fifties, Shapiro sent off a DNA test kit and learned she was only half Jewish. Within 36 hours she found her biological father, who’d donated sperm as a medical student. It’s a moving account of her emotional state as she pondered her identity and what her sense of family would be in the future.

Inheritance: A Memoir of Genealogy, Paternity, and Love by Dani Shapiro: On a whim, in her fifties, Shapiro sent off a DNA test kit and learned she was only half Jewish. Within 36 hours she found her biological father, who’d donated sperm as a medical student. It’s a moving account of her emotional state as she pondered her identity and what her sense of family would be in the future.

*The Country of Larks: A Chiltern Journey by Gail Simmons: Reprising a trek Robert Louis Stevenson took nearly 150 years before, revisiting sites from a childhood in the Chilterns, and seeing the countryside that will be blighted by a planned high-speed railway line. Although the book has an elegiac air, Simmons avoids dwelling in melancholy, and her writing is a beautiful tribute to farmland that was once saturated with the song of larks.

*The Country of Larks: A Chiltern Journey by Gail Simmons: Reprising a trek Robert Louis Stevenson took nearly 150 years before, revisiting sites from a childhood in the Chilterns, and seeing the countryside that will be blighted by a planned high-speed railway line. Although the book has an elegiac air, Simmons avoids dwelling in melancholy, and her writing is a beautiful tribute to farmland that was once saturated with the song of larks.

(Books not pictured were read from the library or on Kindle.)

Coming tomorrow: Other superlatives and some statistics.

Imitation Is the Sincerest Form of Flattery: Costello, O’Shaughnessy & Smyth

These three books – two novels and a memoir – pay loving tribute to a particular nineteenth- or twentieth-century writer. In each case, the author incorporates passages of pastiche, moving beyond thematic similarity to make their language an additional homage.

Although I enjoyed the three books very much, they differ in terms of how familiar you should be with the source material before embarkation. So while they were all  reads for me, I have added a note below each review to indicate the level of prior knowledge needed.

reads for me, I have added a note below each review to indicate the level of prior knowledge needed.

The River Capture by Mary Costello

Luke O’Brien has taken a long sabbatical from his teaching job in Dublin and is back living at the family farm beside the river in Waterford. Though only in his mid-thirties, he seems like a man of sorrows, often dwelling on the loss of parents, aunts and romantic relationships with both men and women. He takes quiet pleasure in food, the company of pets, and books, including his extensive collection on James Joyce, about whom he’d like to write a tome of his own. The novel’s very gentle crisis comes when Luke falls for Ruth and it emerges that her late father ruined his beloved Aunt Ellen’s reputation.

Luke O’Brien has taken a long sabbatical from his teaching job in Dublin and is back living at the family farm beside the river in Waterford. Though only in his mid-thirties, he seems like a man of sorrows, often dwelling on the loss of parents, aunts and romantic relationships with both men and women. He takes quiet pleasure in food, the company of pets, and books, including his extensive collection on James Joyce, about whom he’d like to write a tome of his own. The novel’s very gentle crisis comes when Luke falls for Ruth and it emerges that her late father ruined his beloved Aunt Ellen’s reputation.

At this point a troubled Luke is driven into 100+ pages of sinuous contemplation, a bravura section of short fragments headed by questions. Rather like a catechism, it’s a playful way of organizing his thoughts and likely more than a little Joycean in approach – I’ve read Portrait of the Artist and Dubliners but not Ulysses or Finnegans Wake, so I feel less than able to comment on the literary ventriloquism, but I found this a pleasingly over-the-top stream-of-consciousness that ranges from the profound (“What fear suddenly assails him? The arrival of the noonday demon”) to the scatological (“At what point does he urinate? At approximately three-quarters of the way up the avenue”).

While this doesn’t quite match Costello’s near-perfect novella, Academy Street, it’s an impressive experiment in voice and style, and the treatment of Luke’s bisexuality struck me as sensitive – an apt metaphorical manifestation of the novel’s focus on fluidity. (See also Susan’s excellent review.)

Why Joyce? “integrity … commitment to the quotidian … refusal to take conventions for granted”

Familiarity required: Moderate

Also recommended: The Sixteenth of June by Maya Lang

With thanks to Canongate for the free copy for review.

In Love with George Eliot by Kathy O’Shaughnessy

Many characters, fictional and historical, are in love with George Eliot over the course of this debut novel by a literary editor. The whole thing is a book within a book – fiction being written by Kate, an academic at London’s Queen Elizabeth College who’s preparing for two conferences on Eliot and a new co-taught course on life writing at the same time as she completes her novel, which blends biographical information and imagined scenes.

1857: Eliot is living with George Henry Lewes, her common-law husband, and working on Adam Bede, which becomes a runaway success, not least because of speculation about its anonymous author. 1880: The great author’s death leaves behind a mentally unstable widower 20 years her junior, John Walter Cross, once such a close family friend that she and Lewes called him “Nephew.”

1857: Eliot is living with George Henry Lewes, her common-law husband, and working on Adam Bede, which becomes a runaway success, not least because of speculation about its anonymous author. 1880: The great author’s death leaves behind a mentally unstable widower 20 years her junior, John Walter Cross, once such a close family friend that she and Lewes called him “Nephew.”

Between these points are intriguing vignettes from Eliot’s life with her two great loves, and insight into her scandalous position in Victorian society. Her estrangement from her dear brother (the model for Tom in The Mill on the Floss) is a plangent refrain, while interactions with female friends who have accepted the norms of marriage and motherhood reveal just how transgressive her life is perceived to be.

In the historical sections O’Shaughnessy mimics Victorian prose ably, yet avoids the convoluted syntax that can make Eliot challenging. I might have liked a bit more of the contemporary story line, in which Kate and an alluring colleague make their way to Venice (the site of Eliot’s legendarily disastrous honeymoon trip with Cross), but by making this a minor thread O’Shaughnessy ensures that the spotlight remains on Eliot throughout.

Highlights: A cameo appearance by Henry James; a surprisingly sexy passage in which Cross and Eliot read Dante aloud to each other and share their first kiss.

Why Eliot? “As an artist, this was her task, to move the reader to see people in the round.”

Familiarity required: Low

Also recommended: 142 Strand by Rosemary Ashton, Sophie and the Sibyl by Patricia Duncker, and My Life in Middlemarch by Rebecca Mead

With thanks to Scribe UK for the free copy for review.

All the Lives We Ever Lived: Seeking Solace in Virginia Woolf by Katharine Smyth

Smyth first read To the Lighthouse in Christmas 2001, during her junior year abroad at Oxford. Shortly thereafter her father had surgery in Boston to remove his bladder, one of many operations he’d had during a decade battling cancer. But even this new health scare wasn’t enough to keep him from returning to his habitual three bottles of wine a day. Woolf was there for Smyth during this crisis and all the time leading up to her father’s death, with Lighthouse and Woolf’s own life reflecting Smyth’s experience in unanticipated ways. The Smyths’ Rhode Island beach house, for instance, was reminiscent of the Stephens’ home in Cornwall. Woolf’s mother’s death was an end to the summer visits, and to her childhood; Lighthouse would become her elegy to those bygone days.

Smyth first read To the Lighthouse in Christmas 2001, during her junior year abroad at Oxford. Shortly thereafter her father had surgery in Boston to remove his bladder, one of many operations he’d had during a decade battling cancer. But even this new health scare wasn’t enough to keep him from returning to his habitual three bottles of wine a day. Woolf was there for Smyth during this crisis and all the time leading up to her father’s death, with Lighthouse and Woolf’s own life reflecting Smyth’s experience in unanticipated ways. The Smyths’ Rhode Island beach house, for instance, was reminiscent of the Stephens’ home in Cornwall. Woolf’s mother’s death was an end to the summer visits, and to her childhood; Lighthouse would become her elegy to those bygone days.

Often a short passage by or about Woolf is enough to launch Smyth back into her memories. As an only child, she envied the busy family life of the Ramsays in Lighthouse. She delves into the mystery of her parents’ marriage and her father’s faltering architecture career. She also undertakes Woolf tourism, including the Cornwall cottage, Knole, Charleston and Monk’s House (where Woolf wrote most of Lighthouse). Her writing is dreamy, mingling past and present as she muses on time and grief. The passages of Woolf pastiche are obvious but short enough not to overstay their welcome; as in the Costello, they tend to feature water imagery. It’s a most unusual book in the conception, but for Woolf fans especially, it works. However, I wished I had read Lighthouse more recently than 16.5 years ago – it’s one to reread.

Why Woolf? “I think it’s Woolf’s mastery of moments like these—moments that hold up a mirror to our private tumult while also revealing how much we as humans share—that most draws me to her.”

Undergraduate wisdom: “Woolf’s technique: taking a very complex (usually female) character and using her mind as an emblem of all minds” [copied from notes I took during a lecture on To the Lighthouse in a “Modern Wasteland” course during my sophomore year of college]

Familiarity required: High

Also recommended: Virginia Woolf in Manhattan by Maggie Gee, Vanessa and Her Sister by Priya Parmar, and Adeline by Norah Vincent

With thanks to Atlantic Books for the free copy for review.

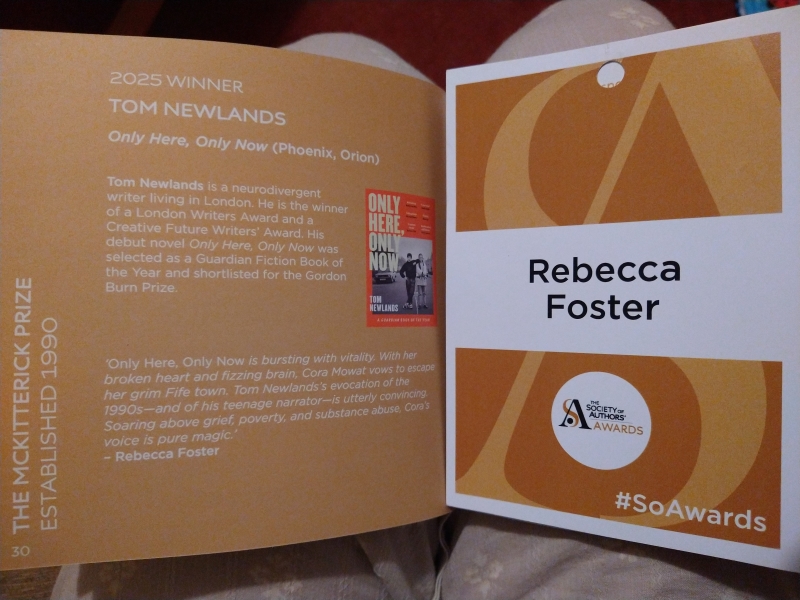

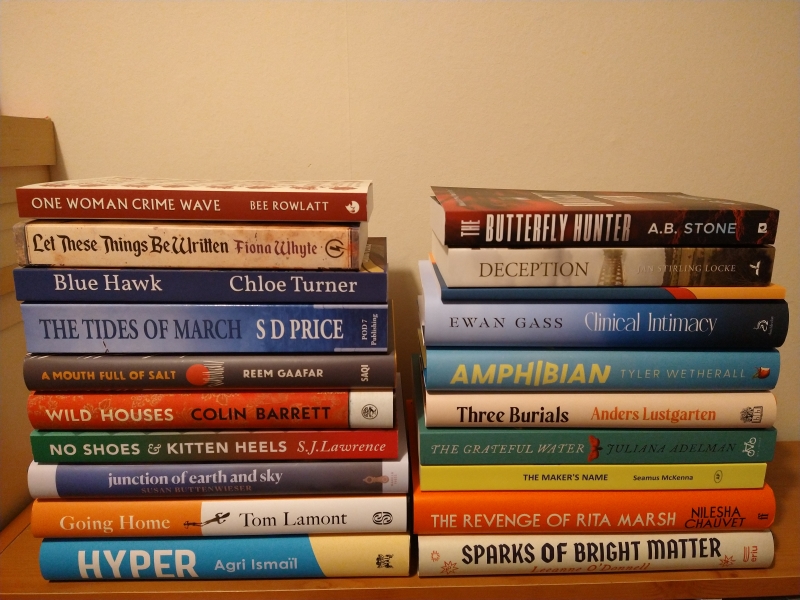

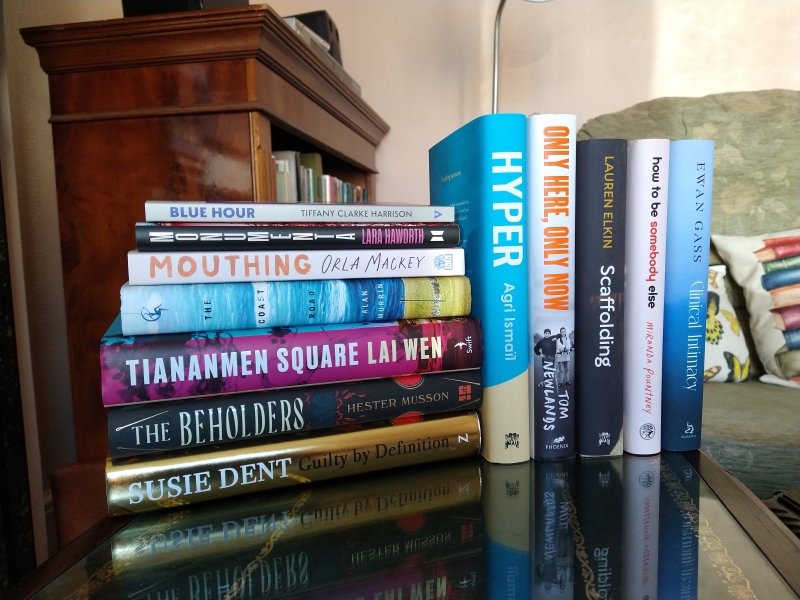

Etymology and Shakespeare studies are the keys to solving a cold case in Susie Dent’s clever, engrossing mystery, Guilty by Definition.

Etymology and Shakespeare studies are the keys to solving a cold case in Susie Dent’s clever, engrossing mystery, Guilty by Definition. Psychoanalysis, motherhood, and violence against women are resounding themes in Lauren Elkin’s Scaffolding. As history repeats itself one sweltering Paris summer, the personal and political structures undergirding the protagonists’ parallel lives come into question. This fearless, sophisticated work ponders what to salvage from the past—and what to tear down.

Psychoanalysis, motherhood, and violence against women are resounding themes in Lauren Elkin’s Scaffolding. As history repeats itself one sweltering Paris summer, the personal and political structures undergirding the protagonists’ parallel lives come into question. This fearless, sophisticated work ponders what to salvage from the past—and what to tear down. Clinical Intimacy’s mysterious antihero comes to life through interviews with his family, friends and clients. The brilliant oral history format builds a picture of isolation among vulnerable populations, only alleviated by care and touch—especially during Covid-19. Ewan Gass’s intricate story reminds us of the ultimate unknowability of other people.

Clinical Intimacy’s mysterious antihero comes to life through interviews with his family, friends and clients. The brilliant oral history format builds a picture of isolation among vulnerable populations, only alleviated by care and touch—especially during Covid-19. Ewan Gass’s intricate story reminds us of the ultimate unknowability of other people.

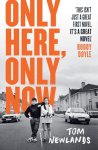

Only Here, Only Now is bursting with vitality. With her broken heart and fizzing brain, Cora Mowat vows to escape her grim Fife town. Tom Newlands’s evocation of the 1990s—and of his teenage narrator—is utterly convincing. Soaring above grief, poverty, and substance abuse, Cora’s voice is pure magic.

Only Here, Only Now is bursting with vitality. With her broken heart and fizzing brain, Cora Mowat vows to escape her grim Fife town. Tom Newlands’s evocation of the 1990s—and of his teenage narrator—is utterly convincing. Soaring above grief, poverty, and substance abuse, Cora’s voice is pure magic.

Hyper by Agri Ismaïl [I longlisted it – and then shortlisted it – but was outvoted]

Hyper by Agri Ismaïl [I longlisted it – and then shortlisted it – but was outvoted] How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney [It had two votes to make the shortlist, but because it was so similar to Scaffolding in its basics (a thirtysomething woman in a big city, the question of motherhood, and pregnancy loss) we decided to cut it.]

How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney [It had two votes to make the shortlist, but because it was so similar to Scaffolding in its basics (a thirtysomething woman in a big city, the question of motherhood, and pregnancy loss) we decided to cut it.]