Buddy Reads: Kilmeny of the Orchard by L.M. Montgomery & The Waterfall by Margaret Drabble

Buddy reading and other coordinated challenges are a good excuse to read the sort of books one doesn’t always get to, especially the more obscure classics. This was my third Lucy Maud Montgomery novel within a year and a bit, and my first contribution to Ali’s ongoing year with Margaret Drabble.

{SPOILERS IN BOTH OF THE FOLLOWING REVIEWS}

Kilmeny of the Orchard by L. M. Montgomery (1910)

I’ve participated in Canadian bloggers Naomi of Consumed by Ink and Sarah Emsley’s readalongs of three Montgomery works now. The previous two were Jane of Lantern Hill and The Story Girl. This sweet but rather outdated novella reminded me more of the latter (no surprise as it was published just a year before it) because of the overall sense of lightness and the male perspective, which isn’t what those familiar with the Anne and Emily books might expect from Montgomery.

Eric Marshall travels to Prince Edward Island one May to be the temporary schoolmaster in Lindsay, filling in for an ill friend. At his graduation from Queenslea College, his cousin David Baker had teased him about his apparent disinterest in girls. He arrives on the island to an early summer idyll and soon wanders into an orchard where a beautiful young woman is playing a violin.

Eric Marshall travels to Prince Edward Island one May to be the temporary schoolmaster in Lindsay, filling in for an ill friend. At his graduation from Queenslea College, his cousin David Baker had teased him about his apparent disinterest in girls. He arrives on the island to an early summer idyll and soon wanders into an orchard where a beautiful young woman is playing a violin.

This is, of course, Kilmeny Gordon, her first name from a Scottish ballad by James Hogg, and it’s clear she will be the love interest. However, there are a couple of impediments to the romance. One is resistance from Kilmeny’s guardians, the strict aunt and uncle who have cared for her since her wronged mother’s death. But the greater obstacle is Kilmeny’s background – illegitimacy plus a disability that everyone bar Eric views as insuperable: she is mute (or, as the book has it, “dumb”). She hears and understands perfectly well, but communicates via writing on a slate.

There is interesting speculation as to whether her condition is psychological or magically inherited from her late mother, who had taken a vow of silence. Conveniently, cousin David is a doctor specializing in throat and voice problems, so assures Eric and the Gordons that nothing is physically preventing Kilmeny from speech. But she refuses to marry Eric until she can speak. The scene in which she fears for his life and calls out to save him is laughably contrived. The language around disability is outmoded. It’s also uncomfortable that the story’s villain, an adopted Gordon cousin, is characterized only by his Italian heritage.

Like The Story Girl, I found this fairly twee, with an unfortunate focus on beauty (“‘Kilmeny’s mouth is like a love-song made incarnate in sweet flesh,’ said Eric enthusiastically”), and marriage as the goal of life. But it was still a pleasant read, especially for the descriptions of a Canadian spring. (Downloaded from Project Gutenberg) #ReadingKilmeny

The Waterfall by Margaret Drabble (1969)

This was Drabble’s fourth novel; I’ve read the previous three and preferred two of them to this (A Summer Bird-Cage is fab). The setup is similar to The Garrick Year, which I read last year for book club, in that the focus is on a young mother of two who embarks on an affair. When we meet Jane Gray she is awaiting the birth of her second child. Her husband, Malcolm, walked out a few weeks ago, but she has the midwife and her cousin Lucy to rely on. Lucy and her husband, James, trade off staying over with Jane as she recovers from childbirth. James is particularly solicitous and, one night, joins Jane in bed.

This was Drabble’s fourth novel; I’ve read the previous three and preferred two of them to this (A Summer Bird-Cage is fab). The setup is similar to The Garrick Year, which I read last year for book club, in that the focus is on a young mother of two who embarks on an affair. When we meet Jane Gray she is awaiting the birth of her second child. Her husband, Malcolm, walked out a few weeks ago, but she has the midwife and her cousin Lucy to rely on. Lucy and her husband, James, trade off staying over with Jane as she recovers from childbirth. James is particularly solicitous and, one night, joins Jane in bed.

At this point there is a stark shift from third person to first person as Jane confesses that she’s been glossing over the complexities of the situation; sleeping with one’s cousin’s husband is never going to be without emotional fallout. “It won’t, of course, do: as an account, I mean, of what took place”; “Lies, lies, it’s all lies. A pack of lies.” The novel continues to alternate between first and third person as Jane gives us glimpses into her uneasy family-making. I found myself bored through much of it, only perking back up for the meta stuff and the one climactic event. In a way it’s a classic tale of free will versus fate, including the choice of how to frame what happens.

I am no longer capable of inaction – then I will invent a morality that condones me.

It wasn’t so, it wasn’t so. I am getting tired of all this Freudian family nexus, I want to get back to that schizoid third-person dialogue.

The narrative tale. The narrative explanation. That was it, or some of it. I loved James because he was what I had never had: because he drove too fast: because he belonged to my cousin: because he was kind to his own child

(What intriguing punctuation there!) The fast driving and obsession with cars is unsubtle foreshadowing: James nearly dies in a car accident on the way to the ferry to Norway. Jane and her children, Laurie and baby Bianca, are in the car but unhurt. This was the days when seatbelts weren’t required, apparently. “It would have been so much simpler if he had been dead: so natural a conclusion, so poetic in its justice.” The Garrick Year, too, has a near-tragedy involving a car. Like many an adultery story, both novels ask whether an affair changes everything, or nothing. Infidelity and the parenting of young children together don’t amount to the most scintillating material, but it is appealing to see Drabble experimenting with how to tell a story. See also Ali’s review. (Secondhand – Alnwick charity shopping)

Some 2023 Reading Superlatives

Longest book read this year: The Weather Woman by Sally Gardner (457 pages) – not very impressive compared to last year’s 720-page To Paradise. That means I didn’t get through a single doorstopper this year. D’oh!

Longest book read this year: The Weather Woman by Sally Gardner (457 pages) – not very impressive compared to last year’s 720-page To Paradise. That means I didn’t get through a single doorstopper this year. D’oh!

Shortest book read this year: Pitch Black by Youme Landowne and Anthony Horton (40 pages)

Authors I read the most by this year: Margaret Atwood, Deborah Levy and Brian Turner (3 books each); Amy Bloom, Simone de Beauvoir, Tove Jansson, John Lewis-Stempel, W. Somerset Maugham, L.M. Montgomery and Maggie O’Farrell (2 books each)

Publishers I read the most from: (Setting aside the ubiquitous Penguin and its many imprints) Carcanet (11 books) and Picador/Pan Macmillan (also 11), followed by Canongate (7).

My top author discoveries of the year: Michelle Huneven and Julie Marie Wade

My proudest bookish accomplishment: Helping to launch the Little Free Library in my neighbourhood in May, and curating it through the rest of the year (nearly daily tidying; occasional culling; requesting book donations)

Most pinching-myself bookish moments: Attending the Booker Prize ceremony; interviewing Lydia Davis and Anne Enright over e-mail; singing carols after-hours at Shakespeare and Company in Paris

Books that made me laugh: Notes from a Small Island by Bill Bryson, The Librarianist by Patrick deWitt, two by Katherine Heiny, Motherland Fatherland Homelandsexuals by Patricia Lockwood

Books that made me cry: A Heart that Works by Rob Delaney, Lucy by the Sea by Elizabeth Strout, Family Meal by Bryan Washington

The book that was the most fun to read: Romantic Comedy by Curtis Sittenfeld

The book that was the most fun to read: Romantic Comedy by Curtis Sittenfeld

Best book club selections: By the Sea by Abdulrazak Gurnah and The Woman in Black by Susan Hill

Best last lines encountered this year: “And I stood there holding on to this man as though he were the very last person left on this sweet sad place that we call Earth.” (Lucy by the Sea, Elizabeth Strout)

Best last lines encountered this year: “And I stood there holding on to this man as though he were the very last person left on this sweet sad place that we call Earth.” (Lucy by the Sea, Elizabeth Strout)

A book that put a song in my head every time I picked it up: Here and Now by Henri Nouwen (Aqualung song here)

A book that put a song in my head every time I picked it up: Here and Now by Henri Nouwen (Aqualung song here)

Shortest book title encountered: Lo (the poetry collection by Melissa Crowe), followed by Bear, Dirt, Milk and They

Best 2023 book titles: These Envoys of Beauty and You Bury the Birds in My Pelvis

Best book titles from other years: I Want to Die but I Want to Eat Tteokbokki, Before You Suffocate Your Own Fool Self, A Down Home Meal for These Difficult Times, The Cats We Meet Along the Way, We All Want Impossible Things

Best book titles from other years: I Want to Die but I Want to Eat Tteokbokki, Before You Suffocate Your Own Fool Self, A Down Home Meal for These Difficult Times, The Cats We Meet Along the Way, We All Want Impossible Things

Favourite title and cover combo of the year: I Am Homeless If This Is Not My Home by Lorrie Moore (shame the contents didn’t live up to it!)

Biggest disappointment: Speak to Me by Paula Cocozza

A 2023 book that everyone was reading but I decided not to: Prophet Song by Paul Lynch

The worst books I read this year: Monica by Daniel Clowes, They by Kay Dick, Swallowing Geography by Deborah Levy and Self-Portrait in Green by Marie Ndiaye (1-star ratings are extremely rare for me; these were this year’s four)

The downright strangest book I read this year: Motherland Fatherland Homelandsexuals by Patricia Lockwood

The Story Girl by L. M. Montgomery (1911) #ReadingStoryGirl

Six months after the Jane of Lantern Hill readalong, Canadian bloggers Naomi (Consumed by Ink) and Sarah Emsley have chosen an earlier work by Lucy Maud Montgomery, The Story Girl, and its sequel The Golden Road, for November buddy reading.

The book opens one May as brothers Felix and Beverley King are sent from Toronto to Prince Edward Island to stay with an aunt and uncle while their father is away on business. Beverley tells us about their thrilling six months of running half-wild with their cousins Cecily, Dan, Felicity, and Sara Stanley – better known by her nickname of the Story Girl, also to differentiate her from another Sara – and the hired boy, Peter. This line gives a sense of the group’s dynamic: “Felicity to look at—the Story Girl to tell us tales of wonder—Cecily to admire us—Dan and Peter to play with—what more could reasonable fellows want?”

Felicity is pretty and domestically inclined; Sara knows it would be better to be useful like Felicity, but all she has is her storytelling ability. Some are fantasy (“The Wedding Veil of the Proud Princess”); some are local tales that have passed into folk memory (“How Betty Sherman Won a Husband”). Beverley is in raptures over the Story Girl’s orations: “if voices had colour, hers would have been like a rainbow. It made words live. … we had listened entranced. I have written down the bare words of the story, as she told it; but I can never reproduce the charm and colour and spirit she infused into it. It lived for us.”

The cousins’ adventures are gently amusing and quite tame. They all write down their dreams in notebooks. Peter debates which church denomination to join and the boys engage in a sermon competition. Pat the cat has to be rescued from bewitching, and receives a dose of medicine in lard he licks off his paws and fur. The Story Girl makes a pudding with sawdust instead of cornmeal (reminding me of Anne Shirley and the dead mouse in the plum pudding). Life consistently teaches lessons in humility, as when they are all duped by Billy Robinson and his magic seeds, which he says will change whatever each one most resents – straight hair, plumpness, height; and there is a false alarm about the end of the world.

I found the novel fairly twee and realized at a certain point that I was skimming over more than I was reading. As was my complaint about Jane of Lantern Hill, there is a predictable near-death illness towards the end. The descriptions of Felicity and the Story Girl are purple (“when the Story Girl wreathed her nut-brown tresses with crimson leaves it seemed, as Peter said, that they grow on her—as if the gold and flame of her spirit had broken out in a coronal”); I had to remind myself that this reflects on Beverley more so than on Montgomery. From Naomi’s review of The Golden Road, I think that would be more to my taste because it has a clear plot rather than just stringing together pleasant but mostly forgettable anecdotes.

Still, it’s been fun to discover some of L. M. Montgomery’s lesser-known work, and there are sweet words about cats and the seasons:

“I am very good friends with all cats. They are so sleek and comfortable and dignified. And it is so easy to make them happy.”

“The beauty of winter is that it makes you appreciate spring.”

This effectively captures the long, magical summer days of childhood. I thought about when I was a kid and loved trips up to my mother’s hometown in upstate New York, where her brothers still lived. I was in awe of the Judd cousins’ big house, acres of lawn and untold luxuries such as Nintendo and a swimming pool. I guess I was as star-struck as Beverley. (University library) ![]()

Book Serendipity, Mid-April through Early June

I call it “Book Serendipity” when two or more books that I read at the same time or in quick succession have something in common – the more bizarre, the better. This is a regular feature of mine every few months. Because I usually have 20–30 books on the go at once, I suppose I’m more prone to such incidents. The following are in roughly chronological order.

- Fishing with dynamite takes place in Glowing Still by Sara Wheeler and In Memoriam by Alice Winn.

- Egg collecting (illegal!) is observed and/or discussed in Sea Bean by Sally Huband and The Jay, the Beech and the Limpetshell by Richard Smyth.

- Deborah Levy’s Things I Don’t Want to Know is quoted in What I’d Rather Not Think About by Jente Posthuma and Glowing Still by Sara Wheeler. I then bought a secondhand copy of the Levy on my recent trip to the States.

- “Piss-en-lit” and other folk names for dandelions are mentioned in The House of the Interpreter by Lisa Kelly and The Furrows by Namwali Serpell.

- Buttercups and nettles are mentioned in The House of the Interpreter by Lisa Kelly and Springtime in Britain by Edwin Way Teale (and other members of the Ranunculus family, which includes buttercups, in These Envoys of Beauty by Anna Vaught).

- The speaker’s heart is metaphorically described as green in a poem in Lo by Melissa Crowe and The House of the Interpreter by Lisa Kelly.

- Discussion of how an algorithm can know everything about you in Tomb Sweeping by Alexandra Chang and I’m a Fan by Sheena Patel.

- A brother drowns in The Loved Ones: Essays to Bury the Dead by Madison Davis, What I’d Rather Not Think About by Jente Posthuma, and The Furrows by Namwali Serpell.

A few cases of a book recalling a specific detail from an earlier read:

- This metaphor in The Chosen by Elizabeth Lowry links it to The Marriage Portrait by Maggie O’Farrell, another work of historical fiction I’d read not long before: “He has further misgivings about the scalloped gilt bedside table, which wouldn’t look of place in the palazzo of an Italian poisoner.”

- This reference in The Education of Harriet Hatfield by May Sarton links it back to Chase of the Wild Goose by Mary Louisa Gordon (could it be the specific book she had in mind? I suspect it was out of print in 1989, so it’s more likely it was Elizabeth Mavor’s 1971 biography The Ladies of Llangollen): “Do you have a book about those ladies, the eighteenth-century ones, who lived together in some remote place, but everyone knew them?”

- This metaphor in Things My Mother Never Told Me by Blake Morrison links it to The Chosen by Elizabeth Lowry: “Moochingly revisiting old places, I felt like Thomas Hardy in mourning for his wife.”

- A Black family is hounded out of a majority-white area by harassment in The Education of Harriet Hatfield by May Sarton and Ordinary Notes by Christina Sharpe.

Wartime escapees from prison camps are helped to freedom, including with the help of a German typist, in My Father’s House by Joseph O’Connor and In Memoriam by Alice Winn.

Wartime escapees from prison camps are helped to freedom, including with the help of a German typist, in My Father’s House by Joseph O’Connor and In Memoriam by Alice Winn.

- A scene of eating a deceased relative’s ashes in 19 Claws and a Black Bird by Agustina Bazterrica and The Loved Ones by Madison Davis.

- A girl lives with her flibbertigibbet mother and stern grandmother in “Wife Days,” one story from How Strange a Season by Megan Mayhew Bergman, and Jane of Lantern Hill by L.M. Montgomery.

- Macramé is mentioned in How Strange a Season by Megan Mayhew Bergman, The Memory of Animals by Claire Fuller, Floppy by Alyssa Graybeal, and Sidle Creek by Jolene McIlwain.

- A fascination with fractals in Floppy by Alyssa Graybeal and one story in Sidle Creek by Jolene McIlwain. They are also mentioned in one essay in These Envoys of Beauty by Anna Vaught.

- I found disappointed mentions of the fact that characters wear blackface in Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Little Town on the Prairie in Monsters by Claire Dederer and, the very next day, Ordinary Notes by Christina Sharpe.

- Moon jellyfish are mentioned in the Blood and Cord anthology edited by Abi Curtis, Floppy by Alyssa Graybeal, and Sea Bean by Sally Huband.

- A Black author is grateful to their mother for preparing them for life in a white world in the memoirs-in-essays I Can’t Date Jesus by Michael Arceneaux and Ordinary Notes by Christina Sharpe.

- The children’s book The Owl Who Was Afraid of the Dark by Jill Tomlinson is mentioned in The Jay, the Beech and the Limpetshell by Richard Smyth and These Envoys of Beauty by Anna Vaught.

- The protagonist’s father brings home a tiger as a pet/object of display in The Marriage Portrait by Maggie O’Farrell and The Memory of Animals by Claire Fuller.

- Bloor Street, Toronto is mentioned in Jane of Lantern Hill by L.M. Montgomery and Ordinary Notes by Christina Sharpe.

- Ralph Waldo Emerson’s thinking about the stars is quoted in Jane of Lantern Hill by L.M. Montgomery and These Envoys of Beauty by Anna Vaught.

- Wondering whether a marine animal would be better off in captivity, where it could live much longer, in The Memory of Animals by Claire Fuller (an octopus) and Sea Bean by Sally Huband (porpoises).

Martha Gellhorn is mentioned in The Collected Regrets of Clover by Mikki Brammer and Monsters by Claire Dederer.

Martha Gellhorn is mentioned in The Collected Regrets of Clover by Mikki Brammer and Monsters by Claire Dederer.

- Characters named June in “Indigo Run,” the novella-length story in How Strange a Season by Megan Mayhew Bergman, and The Cats We Meet Along the Way by Nadia Mikail.

- “Explicate!” is a catchphrase uttered by a particular character in Girls They Write Songs About by Carlene Bauer and The Lake Shore Limited by Sue Miller.

- It’s mentioned that people used to get dressed up for going on airplanes in Fly Girl by Ann Hood and The Lights by Ben Lerner.

- Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn is a setting in The Lights by Ben Lerner and Grave by Allison C. Meier.

- Last year I read Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow by Gabrielle Zevin, in which Oregon Trail re-enactors (in a video game) die of dysentery; this is also a live-action plot point in “Pioneers,” one story in Lydia Conklin’s Rainbow Rainbow.

- A bunch (4 or 5) of Italian American sisters in Circling My Mother by Mary Gordon and Hello Beautiful by Ann Napolitano.

What’s the weirdest reading coincidence you’ve had lately?

Jane of Lantern Hill by L.M. Montgomery (1937) #ReadingLanternHill

I’m grateful to Canadian bloggers Naomi (Consumed by Ink) and Sarah for hosting the readalong: It’s been a pure pleasure to discover this lesser-known work by Lucy Maud Montgomery.

{SOME SPOILERS IN THE FOLLOWING}

Like Anne of Green Gables, this is a cosy novel about finding a home and a family. Fairytale-like in its ultimate optimism, it nevertheless does not avoid negative feelings. It also seemed to me ahead of its time in how it depicts parental separation.

Jane Victoria Stuart lives with her beautiful, flibbertigibbet mother and strict grandmother in a “shabby genteel” mansion on the ironically named Gay Street in Toronto. Grandmother calls her Victoria and makes her read the Bible to the family every night, a ritual Jane hates. Jane is an indifferent student, though she loves writing, and her best friend is Jody, an orphan who is in service next door. Her mother is a socialite breezing out each evening, but she doesn’t seem jolly despite all the parties. Jane has always assumed her father is dead, so it is a shock when a girl at school shares the rumour that her father is alive and living on Prince Edward Island. Apparently, divorce was difficult in Canada at that time and would have required a trip to the USA, so for nearly a decade the couple have been estranged.

It’s not just Jane who feels imprisoned on Gay Street: her mother and Jody are both suffering in their own ways, and long to live unencumbered by others’ strictures. For Jane, freedom comes when her father requests custody of her for the summer. Grandmother is of a mind to ignore the summons, but the wider family advise her to heed it. Initially apprehensive, Jane falls in love with PEI and feels like she’s known her father, a jocular writer, all the time. They’re both romantics and go hunting for a house that will feel like theirs right away. Lantern Hill fits the bill, and Jane delights in playing the housekeeper and teaching herself to cook and garden. Returning to Toronto in the autumn is a wrench, but she knows she’ll be back every summer. It’s an idyll precisely because it’s only part time; it’s a retreat.

Jane is an appealing heroine with her can-do attitude. Her everyday adventures are sweet – sheltering in a barn when the car breaks down, getting a reward and her photo in the paper for containing an escaped circus lion – but I was less enamoured with the depiction of the quirky locals. The names alone point to country bumpkin stereotypes: Shingle Snowbeam, Ding-dong, the Jimmy Johns. I did love Little Aunt Em, however, with her “I smack my lips over life” outlook. Meddlesome Aunt Irene could have been less one-dimensional; Jody’s adoption by the Titus sisters is contrived (and closest in plot to Anne); and Jane’s late illness felt unnecessary. While frequent ellipses threatened to drive me mad, Montgomery has sprightly turns of phrase: “A dog of her acquaintance stopped to speak to her, but Jane ignored him.”

Could this have been one of the earliest stories of a child who shuttles back and forth between separated or divorced parents? I wondered if it was considered edgy subject matter for Montgomery. There is, however, an indulging of the stereotypical broken-home-child fantasy of the parents still being in love and reuniting. If this is a fairytale setup, Grandmother is the evil ogre who keeps the princess(es) locked up in a gloomy castle until the noble prince’s rescue. I’m sure both Toronto and PEI are lovely in their own way – alas, I’ve never been to Canada – and by the end Montgomery offers Jane a bright future in both.

Small qualms aside, I loved reading Jane of Lantern Hill and would recommend it to anyone who enjoyed the Anne books. It’s full of the magic of childhood. What struck me most, and will stick with me, is the exploration of how the feeling of being at home (not just having a house to live in) is essential to happiness. (University library) ![]()

#ReadingLanternHill

Buy Jane of Lantern Hill from Bookshop.org [affiliate link]

Marilla of Green Gables by Sarah McCoy

There’s no doubt about it: fans of Lucy Maud Montgomery’s Anne series will throng to read Sarah McCoy’s prequel. McCoy was inspired by the brief moment in Anne of Green Gables when Marilla tells Anne that John Blythe used to be her beau. Just like Anne, she wanted to know the story behind that offhand remark.

So although Marilla of Green Gables begins in 1876 with a short prologue in which Matthew and Marilla decide to ‘get a boy’ to help around the place, most of it is set in 1837–8, with Marilla taking a break from her schooling to assist her parents, Hugh and Clara (it’s no coincidence that these are the names of L.M. Montgomery’s parents), in the months before her new sibling is to arrive. Brother Matthew is 21 and testing out adulthood, but Marilla is just 13 and impressionable. John Blythe offers to bring her the school readings she’s missed out on, and later invites her to the Avonlea May Picnic. It’s clear she’s smitten.

So although Marilla of Green Gables begins in 1876 with a short prologue in which Matthew and Marilla decide to ‘get a boy’ to help around the place, most of it is set in 1837–8, with Marilla taking a break from her schooling to assist her parents, Hugh and Clara (it’s no coincidence that these are the names of L.M. Montgomery’s parents), in the months before her new sibling is to arrive. Brother Matthew is 21 and testing out adulthood, but Marilla is just 13 and impressionable. John Blythe offers to bring her the school readings she’s missed out on, and later invites her to the Avonlea May Picnic. It’s clear she’s smitten.

Aunt Izzy, a dressmaker from St. Catharines, arrives in time to cheer her twin sister through the impending birth and ends up being Marilla’s new role model. She’s fanciful, exuberant and spontaneous and believes “A young girl needs as much time to dream as possible,” surely making her a deliberate precursor of Anne Shirley. Indeed, much of the fun of reading this book is in spotting the seeds of the Anne books: Clara and Izzy making their famous redcurrant wine and laughing about the time Clara lost a thumbnail in the mix; meeting Rachel White (Lynde) at a sewing circle; a visit to the orphanage in Hopetown; raspberry cordial at a picnic; the Ladies’ Aid Society; and looking to a mistake-free tomorrow.

Before long, though, personal and political upheaval take their toll at Green Gables and drive a wedge between Marilla and John. I found Part Two significantly less engaging, what with all the talk of Reformers versus Loyalists (though I did enjoy glimpses of escaped slaves’ experiences in Canada). I tend not to read anything approaching a romance novel, so I groaned to find that there’s not one but two Mr. Darcy-esque wet-shirt scenes featuring John.

This is not meant to be a substitute for reading Montgomery’s own work; if anything it’s prompted me to reread the original series as soon as I can. While I wouldn’t call Marilla a must-read for fans, then, if you enjoy women’s historical fiction set in the nineteenth century, you may want to pick up this companion volume anyway.

My rating: ![]()

Marilla of Green Gables was published by William Morrow on October 23rd. My thanks to publicist Beth Parker for the proof copy for review. Sarah McCoy is the author of four previous works of fiction, including The Mapmaker’s Children and The Baker’s Daughter.

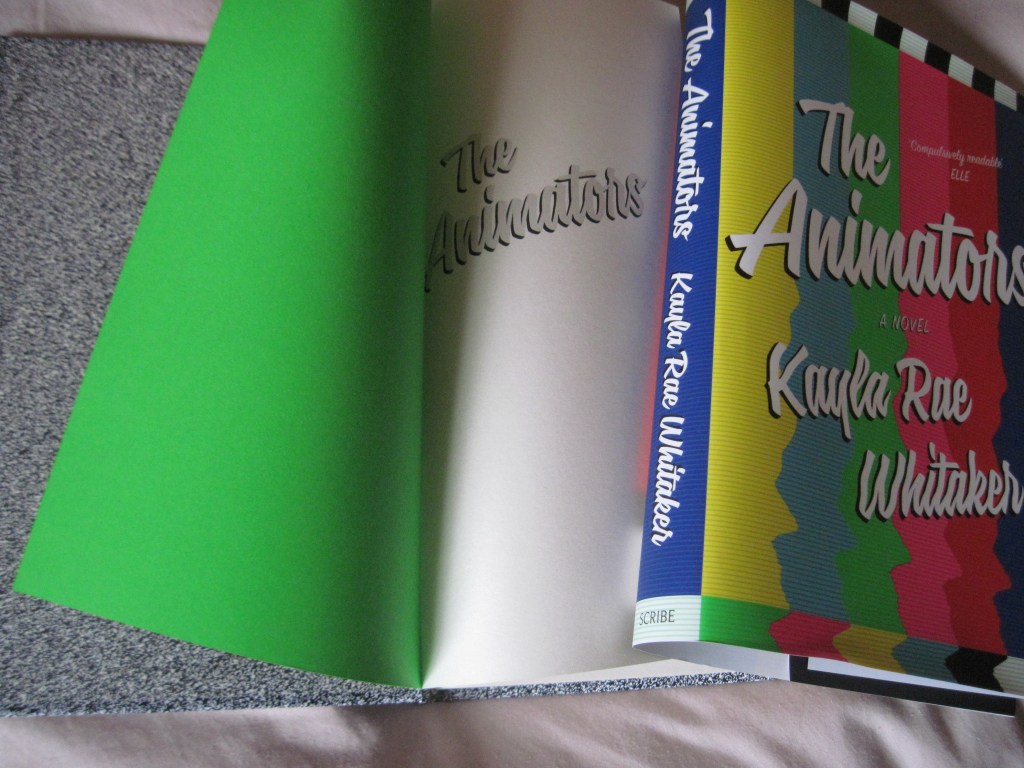

4 Reasons to Love Kayla Rae Whitaker’s The Animators

I have way too much to say about this terrific debut novel, and there’s every danger of me slipping into plot summary because, though it seems lighthearted on the surface, there’s a lot of meat to this story of the long friendship between two female animators. So I’m going to adapt a format that has worked well for other bloggers (e.g. Carolyn at Rosemary and Reading Glasses) and pull out four reasons why you must be sure not to miss this book.

I have way too much to say about this terrific debut novel, and there’s every danger of me slipping into plot summary because, though it seems lighthearted on the surface, there’s a lot of meat to this story of the long friendship between two female animators. So I’m going to adapt a format that has worked well for other bloggers (e.g. Carolyn at Rosemary and Reading Glasses) and pull out four reasons why you must be sure not to miss this book.

- Bosom Friends. Have you ever had, or longed for, what Anne Shirley calls a “bosom friend”? If so, you’ll love watching the friendship develop between narrator Sharon Kisses and her business partner, Mel Vaught. In many ways they are opposites. Lanky, blonde Mel is a loud, charismatic lesbian who uses drugs and alcohol to fuel a manic pace of life. She’s the life of every party. Sharon, on the other hand, is a curvy brunette and neurotic introvert who’s always falling in love with men but never achieving real relationships. They meet in Professor McIntosh’s Introduction to Sketch class at a small college and a decade later are still working together. They win acclaim for their first full-length animated feature, Nashville Combat, based on Mel’s dysfunctional upbringing in the Central Florida swamps. But they see each other through some really low lows, too, like the death of Mel’s mother and Sharon’s punishing recovery from a stroke at the age of 32.

She was the first person to see me as I had always wanted to be seen. It was enough to indebt me to her forever.

- The Value of Work. Kayla Rae Whitaker was inspired by her childhood obsession with dark, quirky cartoons like Beavis and Butthead and Ren and Stimpy. Books about artists sometimes present the work as magically fully-formed, rather than showing the arduous process behind it. Here, though, you track Mel and Sharon’s next film from a set of rough sketches in a secret notebook to a polished comic, following it through storyboarding, filling-in and final edits. It’s a year of all-nighters, poor diet and substance abuse. But work – especially the autobiographical projects these characters create – is also saving. Even when it seems the well has run dry, creativity always resurges. I also appreciated how the novel contrasts the women’s public and private personas and imagines their professional legacy.

The work will always be with you, will come back to you if it leaves, and you will return to it to find that you have, in fact, gotten better, gotten sharper. It happens to you while you are asleep inside.

- Road Trips and Rednecks. I love a good road trip narrative, and this novel has two. First there’s the drive down to Florida for Mel to identify her mother, and then there’s Sharon’s sheepish return to her hometown of Faulkner, Kentucky. Here’s where the book really takes off. The sharp, sassy dialogue sparkles throughout, but the scenes with Sharon’s mom and sister are particularly hilarious. What’s more, the contrast between the American heartland and the flashy New York City life Mel and Sharon have built works brilliantly. Although in the Kentucky section Whitaker portrays some obese Americans you’d be tempted to call white trash, she never resorts to cruel hillbilly stereotypes. The author herself is from rural eastern Kentucky and paints the place in a tender light. She even makes Louisville – where the friends go to meet up with Sharon’s old neighbor and first crush, Teddy Caudill – sound like quite an appealing tourist destination!

I used it to hate it here. How could I have possibly hated this? This is me. I sprang from this place.

I love the attention to detail evident in the book design, especially the black-and-white TV fuzz of the covers under the dust jacket, and the pop of neon green on the inside of the endpapers.

- Open Your Trunk. This is a mantra arising from Mel and Sharon’s second movie, Irrefutable Love, which is autobiographical for Sharon this time – revolving around a traumatic incident from her shared past with Teddy, her string of crushes, and her stroke recovery. One powerful message of the novel is that you can’t move on in life unless you confront the crap that’s happened to you. As humorous as it is, it’s also a weighty book in this respect. It has three pivot points, moments so grim and surprising that I could hardly believe Whitaker dared to put them in. (The first is Sharon’s stroke; the others I won’t spoil.) This means the ending is not the super-happy one I might have wanted, but it’s realistic.

Anything that makes you in that way, anything that makes you hurt and hungry in that way, is worth investigating. … When you take the things that happen to you, the things that make you who are, and you use them, you own them.

I thought the timeline could be a little tighter and the novel was unnecessarily crass in places. For me, the road trips were the best bits and the rest never quite matched up. But this is still bound to be one of my top novels of the year. I think every reader will see him/herself in Sharon, and we all know a Mel; for some it might be the other way around. Like A Little Life and even The Essex Serpent, this asks how friendship and work can carry us through. Meanwhile, the cartooning world and the Kentucky–New York City dichotomy together feel like a brand new setting for a literary tragicomedy.

An early favorite for 2017. Don’t miss it.

The Animators was published by Random House and Scribe UK on January 31st. My thanks to Sophie Leeds of Scribe for sending a free copy for review.

My rating: ![]()

This was my eighth book by Norman and felt most similar to

This was my eighth book by Norman and felt most similar to  Ordorica, also a poet, immediately sets an elegiac tone by revealing Sam’s untimely death soon after the end of their freshman year. To cope with losing the love of his life, Daniel writes this text as if it’s an extended letter to Sam, recounting the course of their relationship – from strangers to best friends to secret lovers – and telling of his summer spent in Mexico exploring his family history, especially the parallels between his life and that of his late uncle and namesake, who was brave enough to be openly gay in the early days of the AIDS crisis.

Ordorica, also a poet, immediately sets an elegiac tone by revealing Sam’s untimely death soon after the end of their freshman year. To cope with losing the love of his life, Daniel writes this text as if it’s an extended letter to Sam, recounting the course of their relationship – from strangers to best friends to secret lovers – and telling of his summer spent in Mexico exploring his family history, especially the parallels between his life and that of his late uncle and namesake, who was brave enough to be openly gay in the early days of the AIDS crisis. I spied this in one of Susan’s monthly previews. (If you haven’t already subscribed to

I spied this in one of Susan’s monthly previews. (If you haven’t already subscribed to

The Scarlet Letter by Nathaniel Hawthorne

The Scarlet Letter by Nathaniel Hawthorne A History of God by Karen Armstrong

A History of God by Karen Armstrong Secrets in the Dark by Frederick Buechner

Secrets in the Dark by Frederick Buechner The Emperor of All Maladies by Siddhartha Mukherjee

The Emperor of All Maladies by Siddhartha Mukherjee Dinner at the Homesick Restaurant by Anne Tyler

Dinner at the Homesick Restaurant by Anne Tyler