20 Books of Summer, 14–16: Polly Atkin, Nan Shepherd and Susan Allen Toth

I’m still plugging away at the challenge. It’ll be down to the wire, but I should finish and review all 20 books by the 31st! Today I have a chronic illness memoir, a collection of poetry and prose pieces, and a reread of a cosy travel guide.

Some of Us Just Fall: On Nature and Not Getting Better by Polly Atkin (2023)

I was heartened to see this longlisted for the Wainwright Prize. It was a perfect opportunity to recognize the disabled/chronically ill experience of nature and the book achieves just what the award has recognised in recent years: the braiding together of life writing and place-based observation. (Wainwright has also done a great job on diversity this year: there are three books by BIPOC and five by women on the nature writing shortlist alone.)

Polly Atkin knew something was different about her body from a young age. She broke bones all the time, her first at 18 months when her older brother ran into her on his bicycle. But it wasn’t until her thirties that she knew what was wrong – Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and haemochromatosis – and developed strategies to mitigate the daily pain and the drains on her energy and mobility. “Correct diagnosis makes lives bearable,” she writes. “It gives you access to the right treatment. It gives you agency.”

Polly Atkin knew something was different about her body from a young age. She broke bones all the time, her first at 18 months when her older brother ran into her on his bicycle. But it wasn’t until her thirties that she knew what was wrong – Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and haemochromatosis – and developed strategies to mitigate the daily pain and the drains on her energy and mobility. “Correct diagnosis makes lives bearable,” she writes. “It gives you access to the right treatment. It gives you agency.”

The book assembles long-ish fragments, snippets from different points of her past alternating with what she sees on rambles near her home in Grasmere. She writes in some depth about Lake District literature: Thomas De Quincey as well as the Wordsworths – Atkin’s previous book is a biography of Dorothy Wordsworth that spotlights her experience with illness. In describing the desperately polluted state of Windermere, Atkin draws parallels with her condition (“Now I recognise my body as a precarious ecosystem”). Although she spurns the notion of the “Nature Cure,” swimming is a valuable therapy for her.

Theme justifies form here: “This is the chronic life, lived as repetition and variance, as sedimentation of broken moments, not as a linear progression.” For me, there was a bit too much particularity; if you don’t connect to the points of reference, there’s no way in and the danger arises of it all feeling indulgent. Besides, by the time I opened this I’d already read two Ehlers-Danlos memoirs (All My Wild Mothers by Victoria Bennett and Floppy by Alyssa Graybeal) and another reference soon came my way in The Invisible Kingdom by Meghan O’Rourke. So overfamiliarity was a problem. And by the time I forced myself to pick this off of my set-aside shelf and finish it, I’d read Nina Lohman’s stellar The Body Alone. For those newer to reading about chronic illness, though, especially if you also have an interest in the Lakes, it could be an eye-opener.

With thanks to Sceptre (Hodder) for the free copy for review.

Selected Prose & Poetry by Nan Shepherd (2023)

I’d read and enjoyed Shepherd’s The Living Mountain, which has surged in popularity as an early modern nature writing classic thanks to Robert Macfarlane et al. I’m not sure I’d go as far as the executor of the Nan Shepherd Estate, though, who describes her in the Preface as “Taylor Swift in hiking boots.” The pieces reprinted here are from her one published book of poems, In the Cairngorms, and the mixed-genre collection Wild Geese. There is also a 28-page “novella,” Descent from the Cross. After World War I, Elizabeth, a workers’ rights organiser for a paper mill, marries a shell-shocked veteran who wants to write a book but isn’t sure he has either the genius or the dedication. It’s interesting that Shepherd would write about a situation where the wife has the economic upper hand, but the tragedy of the sickly failed author put me in mind of George Gissing or D.H. Lawrence, so didn’t feel fresh. Going by length alone, I would have called this a short story, but I understand why it would be designated a novella, for the scope.

I’d read and enjoyed Shepherd’s The Living Mountain, which has surged in popularity as an early modern nature writing classic thanks to Robert Macfarlane et al. I’m not sure I’d go as far as the executor of the Nan Shepherd Estate, though, who describes her in the Preface as “Taylor Swift in hiking boots.” The pieces reprinted here are from her one published book of poems, In the Cairngorms, and the mixed-genre collection Wild Geese. There is also a 28-page “novella,” Descent from the Cross. After World War I, Elizabeth, a workers’ rights organiser for a paper mill, marries a shell-shocked veteran who wants to write a book but isn’t sure he has either the genius or the dedication. It’s interesting that Shepherd would write about a situation where the wife has the economic upper hand, but the tragedy of the sickly failed author put me in mind of George Gissing or D.H. Lawrence, so didn’t feel fresh. Going by length alone, I would have called this a short story, but I understand why it would be designated a novella, for the scope.

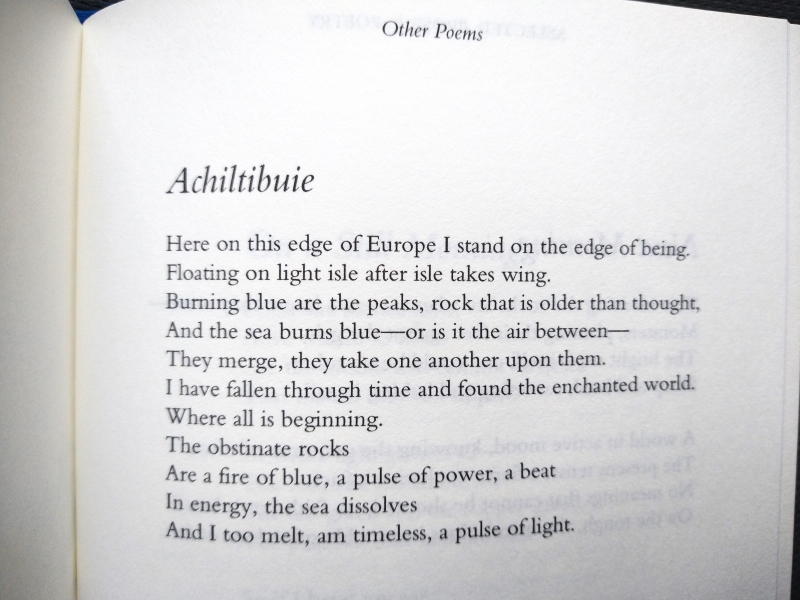

None of the miniature essays – field observations and character studies – stood out to me. About half of the book is given over to poetry. As with the nature writing, there is a feeling of mountain desolation. There are a lot of religious references and hints of the mystical, as in “The Bush,” which opens “In that pure ecstasy of light / The bush is burning bright. / Its substance is consumed away / And only form doth stay”. It’s a mixed bag: some feels very old-fashioned and sentimental, with every other line or, worse, every line rhyming, and some archaic wording and rather impenetrable Scots dialect. It could have been written 100 years before, by Robert Burns if not William Blake. But every so often there is a flash of brilliance. “Blackbird in Snow” is quite a nice one, and reminiscent of Thomas Hardy’s “The Darkling Thrush.” I even found the cryptic lines from “Real Presence” that inspired a song on David Gray’s Skellig. My favourite poem by far was:

Overall, this didn’t engage me; it’s only for Shepherd fanatics and completists. (Won from Galileo Publishers in a Twitter giveaway)

England As You Like It: An Independent Traveler’s Companion by Susan Allen Toth (1995)

A reread. As I was getting ready to go overseas for the first time in the summer of 2003, Toth’s trilogy of memoirs whetted my appetite for travel in Britain. (They’re on my Landmark Books in My Life, Part II list.) This is the middle book and probably the least interesting in that it mostly recounts stays in particular favourite locations, such as Dorset, the Highlands, and various sites in Cornwall. However, I’ve never forgotten her “thumbprint theory,” which means staying a week or more in an area no larger than her thumb covers on a large-scale map, driving an hour or less for day trips. Not for her those cram-it-all-in trips where you race through multiple countries in a week (I have American friends who did Paris, London and Rome within six days, or five countries in eight days; blame it on stingy vacation policies, I guess). Instead, she wants to really bed into one place and have the time to make serendipitous discoveries such as an obscure museum or a rare opening of a private garden.

A reread. As I was getting ready to go overseas for the first time in the summer of 2003, Toth’s trilogy of memoirs whetted my appetite for travel in Britain. (They’re on my Landmark Books in My Life, Part II list.) This is the middle book and probably the least interesting in that it mostly recounts stays in particular favourite locations, such as Dorset, the Highlands, and various sites in Cornwall. However, I’ve never forgotten her “thumbprint theory,” which means staying a week or more in an area no larger than her thumb covers on a large-scale map, driving an hour or less for day trips. Not for her those cram-it-all-in trips where you race through multiple countries in a week (I have American friends who did Paris, London and Rome within six days, or five countries in eight days; blame it on stingy vacation policies, I guess). Instead, she wants to really bed into one place and have the time to make serendipitous discoveries such as an obscure museum or a rare opening of a private garden.

I most liked the early general chapters about how to make air travel bearable, her obsession with maps, her preference for self-catering, and her tendency to take home edible souvenirs. Of course, all the “Floating Facts” are hopelessly out-of-date. This being the early to mid-1990s, she had to order paper catalogues to browse cottage options (I still did this for honeymoon prep in 2006–7) and make international phone calls to book accommodation. She recommends renting somewhere from the National Trust or Landmark Trust. Ordnance Survey maps could be special ordered from the British Travel Bookshop in New York City. Entry fees averaged a few pounds. It’s all so quaint! An Anglo-American time capsule of sorts. I’ve always sensed a kindred spirit in Toth, and those whose taste runs toward the old-fashioned will probably also find her a charming tour guide. I’ve also reviewed the third book, England for All Seasons. (Free from The Book Thing of Baltimore)

August Releases: Bright Fear, Uprooting, The Farmer’s Wife, Windswept

This month I have three memoirs by women, all based on a connection to land – whether gardening, farming or crofting – and a sophomore poetry collection that engages with themes of pandemic anxiety as well as crossing cultural and gender boundaries.

My August highlight:

Bright Fear by Mary Jean Chan

Chan’s Flèche was my favourite poetry collection of 2019. Their follow-up returns to many of the same foundational subjects: race, family, language and sexuality. But this time, the pandemic is a lens through which all is filtered. This is particularly evident in Part I, “Grief Lessons.” “London, 2020” and “Hong Kong, 2003,” on facing pages, contrast Covid-19 with SARS, the major threat when they were a teenager. People have always made assumptions about them based on their appearance or speech. At a time when Asian heritage merited extra suspicion, English was both a means of frank expression and a source of ambivalence:

“At times, English feels like the best kind of evening light. On other days, English becomes something harder, like a white shield.” (from “In the Beginning Was the Word”)

“my Chinese / face struck like the glow of a torch on a white question: / why is your English so good, the compliment uncertain / of itself.” (from “Sestina”)

At the centre of the book, “Ars Poetica,” a multi-part collage incorporating lines from other poets, forms a kind of autobiography in verse. Chan also questions the lines between genres, wondering whether to label their work poetry, nonfiction or fiction (“The novel feels like a springer spaniel running off-/leash the poem a warm basket it returns to always”).

At the centre of the book, “Ars Poetica,” a multi-part collage incorporating lines from other poets, forms a kind of autobiography in verse. Chan also questions the lines between genres, wondering whether to label their work poetry, nonfiction or fiction (“The novel feels like a springer spaniel running off-/leash the poem a warm basket it returns to always”).

The poems’ structure varies, with paragraphs and stanzas of different lengths and placement on the page (including, in one instance, a goblet shape). The enjambment, as you can see in lines I’ve quoted above and below, is noteworthy. Part III, “Field Notes on a Family,” reflects on the pressures of being an only child whose mother would prefer to pretend lives alone rather than with a female partner. The book ends with hope that Chan might be able to be open about their identity. The title references the paradoxical nature of the sublime, beautifully captured via the alliteration that closes “Circles”: “a commotion of coots convincing / me to withstand the quotidian tug-/of-war between terror and love.”

Although Flèche still has the edge for me, this is another excellent work I would recommend even to those wary of poetry.

Some more favourite lines, from “Ars Poetica”:

“What my mother taught me was how

to revere the light language emitted.”

“Home, my therapist suggests, is where

you don’t have to explain yourself.”

With thanks to Faber for the free copy for review.

Three land-based memoirs:

(All:  )

)

Uprooting: From the Caribbean to the Countryside – Finding Home in an English Country Garden by Marchelle Farrell

This Nan Shepherd Prize-winning memoir shares Chan’s attention to pandemic-era restrictions and how they prompt ruminations about identity and belonging. Farrell is from Trinidad but came to the UK as a student and has stayed, working as a psychiatrist and then becoming a wife and mother. Just before Covid hit, she moved to the outskirts of Bath and started rejuvenating her home’s large and neglected garden. Under thematic headings that also correspond to the four seasons, chapters are named after different plants she discovered or deliberately cultivated. The peace she finds in her garden helps her to preserve her mental health even though, with the deaths of George Floyd and so many other Black people, she is always painfully aware of her fragile status as a woman of colour, and sometimes feels trapped in the confining routines of homeschooling. I enjoyed the exploration of postcolonial family history and the descriptions of landscapes large and small but often found Farrell’s metaphors and psychological connections obvious or strained.

This Nan Shepherd Prize-winning memoir shares Chan’s attention to pandemic-era restrictions and how they prompt ruminations about identity and belonging. Farrell is from Trinidad but came to the UK as a student and has stayed, working as a psychiatrist and then becoming a wife and mother. Just before Covid hit, she moved to the outskirts of Bath and started rejuvenating her home’s large and neglected garden. Under thematic headings that also correspond to the four seasons, chapters are named after different plants she discovered or deliberately cultivated. The peace she finds in her garden helps her to preserve her mental health even though, with the deaths of George Floyd and so many other Black people, she is always painfully aware of her fragile status as a woman of colour, and sometimes feels trapped in the confining routines of homeschooling. I enjoyed the exploration of postcolonial family history and the descriptions of landscapes large and small but often found Farrell’s metaphors and psychological connections obvious or strained.

With thanks to Canongate for the free copy for review.

The Farmer’s Wife: My Life in Days by Helen Rebanks

I fancied a sideways look at James Rebanks (The Shepherd’s Life and Wainwright Prize winner English Pastoral) and his regenerative farming project in the Lake District. (My husband spotted their dale from a mountaintop on holiday earlier in the month.) Helen Rebanks is a third-generation farmer’s wife and food and family are the most important things to her. One gets the sense that she has felt looked down on for only ever wanting to be a wife and mother. Her memoir, its recollections structured to metaphorically fall into a typical day, is primarily a defence of the life she has chosen, and secondarily a recipe-stuffed manifesto for eating simple, quality home cooking. (She paints processed food as the enemy.)

I fancied a sideways look at James Rebanks (The Shepherd’s Life and Wainwright Prize winner English Pastoral) and his regenerative farming project in the Lake District. (My husband spotted their dale from a mountaintop on holiday earlier in the month.) Helen Rebanks is a third-generation farmer’s wife and food and family are the most important things to her. One gets the sense that she has felt looked down on for only ever wanting to be a wife and mother. Her memoir, its recollections structured to metaphorically fall into a typical day, is primarily a defence of the life she has chosen, and secondarily a recipe-stuffed manifesto for eating simple, quality home cooking. (She paints processed food as the enemy.)

Growing up, Rebanks started cooking for her family early on, and got a job in a café as a teenager; her mother ran their farm home as a B&B but was forgetful to the point of being neglectful. She met James at 17 and accompanied him to Oxford, where they must have been the only student couple cooking and eating proper food. This period, when she was working an office job, baking cakes for a café, and mourning the devastating foot-and-mouth disease epidemic from a distance, is most memorable. Stories from travels, her wedding, and the births of her four children are pleasant enough, yet there’s nothing to make these experiences, or the telling of them, stand out. I wouldn’t make any of the dishes; most you could find a recipe for anywhere. Eleanor Crow’s black-and-white illustrations are lovely, though.

With thanks to Faber for the free copy for review.

Windswept: Life, Nature and Deep Time in the Scottish Highlands by Annie Worsley

I’d come across Worsley in the Wildlife Trusts’ Seasons anthologies. For a decade she has lived on Red River Croft, in a little-known pocket of northwest Scotland. In word pictures as much as in the colour photographs that illustrate this volume, she depicts it as a wild land shaped mostly by natural forces – also, sometimes, manmade. From one September to the next, she documents wildlife spectacles and the influence of weather patterns. Chronic illness sometimes limited her daily walks to the fence at the cliff-top. (But what a view from there!) There is more here about local history and ecology than any but the keenest Scotland-phile may be interested to read. Worsley also touches on her upbringing in polluted Lancashire, and her former academic career and fieldwork in Papua New Guinea. Her descriptions are full of colours and alliteration, though perhaps a little wordy: “Pale-gold autumnal days are spliced by fickle and feisty bouts of turbulent weather. … Sunrises and sunsets may pour with cinnabar and henna; dawn and dusk can ripple with crimson and purple.” The kind of writing I could appreciate for the length of an essay but not a whole book.

I’d come across Worsley in the Wildlife Trusts’ Seasons anthologies. For a decade she has lived on Red River Croft, in a little-known pocket of northwest Scotland. In word pictures as much as in the colour photographs that illustrate this volume, she depicts it as a wild land shaped mostly by natural forces – also, sometimes, manmade. From one September to the next, she documents wildlife spectacles and the influence of weather patterns. Chronic illness sometimes limited her daily walks to the fence at the cliff-top. (But what a view from there!) There is more here about local history and ecology than any but the keenest Scotland-phile may be interested to read. Worsley also touches on her upbringing in polluted Lancashire, and her former academic career and fieldwork in Papua New Guinea. Her descriptions are full of colours and alliteration, though perhaps a little wordy: “Pale-gold autumnal days are spliced by fickle and feisty bouts of turbulent weather. … Sunrises and sunsets may pour with cinnabar and henna; dawn and dusk can ripple with crimson and purple.” The kind of writing I could appreciate for the length of an essay but not a whole book.

With thanks to William Collins for the free copy for review.

Would you read one or more of these?

Cumbria Sights and Reading & A Return to Sedbergh

We returned on Friday from a one-week reunion with university friends – some we see very often and some less so; we hadn’t all been together since February 2020. After a protracted winter selection process pitting locations and cottages against each other, the nine of us had managed to agree on a converted inn in Appleby-in-Westmorland, Cumbria, and it ended up being the perfect base for us: roomy, with lots of communal space plus en suite rooms for each family unit, and well located.

This was my first time in the Lake District in 17 years, and I particularly enjoyed the outings to Haweswater, Acorn Bank, Keswick and Derwentwater, and Carlisle (that one by train), as well as some low-key walking closer to the cottage.

As apposite reading, I took along:

- Some of Us Just Fall by Polly Atkin: A memoir of chronic illness by a writer based in Grasmere.

- Haweswater by Sarah Hall: Purchased in Sedbergh last year. Hall’s debut novel is set in the run-up to the lake being dammed to provide water for the city of Manchester in 1936, flooding the village of Mardale. I’m finding it rather dry and the local accent over-the-top, but I’ll push through and call it one of my 20 Books of Summer.

- The Farmer’s Wife by Helen Rebanks: A recipe-studded memoir of daily life as the spouse of famous Lake District sheep farmer James Rebanks.

- Wild Fell by Lee Schofield: As featured in my Six Degrees post, a plant-loving and conservation-oriented memoir by the manager of the RSPB Haweswater site.

I also packed, but didn’t get time to read from, books by Margaret Forster and Dorothy Wordsworth. A good showing by women from the northwest!

Though we hadn’t planned on going back so soon, having been for the first time in September, when I learned that Sedbergh was only 40 minutes from where we were staying, I suggested it for a daytrip along with a scenic walk to a waterfall and cake and soft drinks at the Cross Keys Temperance Inn, and even the less book-obsessed of us seemed to enjoy.

My final haul – including, from Carlisle, one book each from a charity shop and Bookcase (above), which I learned about from Simon but actually found kind of overwhelmingly huge and mazelike – cost £9.50 after subtracting the sellback of a partial box of books at Westwood. A good selection of poetry and novellas, plus a favourite I couldn’t resist buying two copies of and might reread as a buddy read with my husband (the Orlean).

Any vacation reading or book hauls for you this August?

Six Degrees of Separation: Romantic Comedy to Wild Fell

This is a fun meme I take part in every few months.

For August we begin with Romantic Comedy by Curtis Sittenfeld, one of my top 2023 releases so far. (See Kate’s opening post.)

#1 Sittenfeld’s protagonist, Sally Milz, writes TV comedy, as does Kristin Newman (That ’70s Show, How I Met Your Mother, etc.), author of What I Was Doing While You Were Breeding, a lighthearted record of her travels and romantic conquests. (She even has a passage that reminds me of Sally’s Danny Horst Rule: “I looked like a thirty-year-old writer. Not like a twenty-year-old model or actress or epically legged songstress, which is a category into which an alarmingly high percentage of Angelenas fall. And, because the city is so lousy with these leggy aliens, regular- to below-average-looking guys with reasonable employment levels can actually get one, another maddening aspect of being a woman in this city.”)

#1 Sittenfeld’s protagonist, Sally Milz, writes TV comedy, as does Kristin Newman (That ’70s Show, How I Met Your Mother, etc.), author of What I Was Doing While You Were Breeding, a lighthearted record of her travels and romantic conquests. (She even has a passage that reminds me of Sally’s Danny Horst Rule: “I looked like a thirty-year-old writer. Not like a twenty-year-old model or actress or epically legged songstress, which is a category into which an alarmingly high percentage of Angelenas fall. And, because the city is so lousy with these leggy aliens, regular- to below-average-looking guys with reasonable employment levels can actually get one, another maddening aspect of being a woman in this city.”)

#2 I didn’t realize when I picked it up in a charity shop that my copy smelled strongly of cigarette smoke. I aired it in kitty litter, then by scented candles, and it still reeks. I reckon I can tolerate the smell long enough to finish it and put it in the Little Free Library, which gets good ventilation. A novel I acquired from the free bookshop we used to have in the mall in town was the only book I can remember having to get rid of before reading because it just smelled too bad (also of cigarettes in that case): My Sister’s Keeper by Jodi Picoult.

#2 I didn’t realize when I picked it up in a charity shop that my copy smelled strongly of cigarette smoke. I aired it in kitty litter, then by scented candles, and it still reeks. I reckon I can tolerate the smell long enough to finish it and put it in the Little Free Library, which gets good ventilation. A novel I acquired from the free bookshop we used to have in the mall in town was the only book I can remember having to get rid of before reading because it just smelled too bad (also of cigarettes in that case): My Sister’s Keeper by Jodi Picoult.

#3 So I didn’t read that, but I have read another Picoult novel, Sing You Home. The author is known for picking a central issue to address in each work, and in that one it was sexuality. Zoe, a music therapist, is married to Max but leaves him for Vanessa – and then decides to sue him for the use of the embryos they created together via IVF. It was the first book I’d read with that dynamic (a previously straight woman enters into a lesbian partnership), but by no means the last. Later came Untamed by Glennon Doyle, Hidden Nature by Alys Fowler, The Fixed Stars by Molly Wizenberg … and one you maybe weren’t expecting: the fantastic memoir First Time Ever by Peggy Seeger. The authors vary in how they account for it. They were gay all along but didn’t realize it? Their orientation changed? Or they just happened to fall in love with someone of the same gender? Seeger doesn’t explain at all, simply records how head-over-heels she was for Ewan MacColl … and then for Irene Pyper Scott.

#3 So I didn’t read that, but I have read another Picoult novel, Sing You Home. The author is known for picking a central issue to address in each work, and in that one it was sexuality. Zoe, a music therapist, is married to Max but leaves him for Vanessa – and then decides to sue him for the use of the embryos they created together via IVF. It was the first book I’d read with that dynamic (a previously straight woman enters into a lesbian partnership), but by no means the last. Later came Untamed by Glennon Doyle, Hidden Nature by Alys Fowler, The Fixed Stars by Molly Wizenberg … and one you maybe weren’t expecting: the fantastic memoir First Time Ever by Peggy Seeger. The authors vary in how they account for it. They were gay all along but didn’t realize it? Their orientation changed? Or they just happened to fall in love with someone of the same gender? Seeger doesn’t explain at all, simply records how head-over-heels she was for Ewan MacColl … and then for Irene Pyper Scott.

#4 Peggy Seeger is one of my heroes these days. I first got into her music through the lockdown livestreams put together by Folk on Foot and have since seen her live and acquired several of her albums, including a Smithsonian Folkways collection of her best-loved folk standards. One of these is, of course, “I’m Gonna Be an Engineer,” which was one of the inspirations for Claire Fuller’s Unsettled Ground.

#4 Peggy Seeger is one of my heroes these days. I first got into her music through the lockdown livestreams put together by Folk on Foot and have since seen her live and acquired several of her albums, including a Smithsonian Folkways collection of her best-loved folk standards. One of these is, of course, “I’m Gonna Be an Engineer,” which was one of the inspirations for Claire Fuller’s Unsettled Ground.

#5 Unsettled Ground, an unusual story of rural poverty and illiteracy, is set in a fictional village modelled on Inkpen, where Nicola Chester lives. Her memoir On Gallows Down, which held particular local interest for me, was shortlisted for the Wainwright Prize last year.

#5 Unsettled Ground, an unusual story of rural poverty and illiteracy, is set in a fictional village modelled on Inkpen, where Nicola Chester lives. Her memoir On Gallows Down, which held particular local interest for me, was shortlisted for the Wainwright Prize last year.

#6 Also shortlisted that year was Wild Fell by Lee Schofield, about his work at RSPB Haweswater. Like Chester, he’s been mired in the struggle to balance sustainable farming with conservation at a beloved place. And like a fellow Lakeland farmer (and previous Wainwright Prize winner for English Pastoral), James Rebanks, he’s trying to be respectful of tradition while also restoring valuable habitats. My husband and I each took a library copy of Wild Fell along to Cumbria last week (about which more anon) and packed it in a backpack for an on-location photo during our wild walk at the very atmospheric Haweswater.

#6 Also shortlisted that year was Wild Fell by Lee Schofield, about his work at RSPB Haweswater. Like Chester, he’s been mired in the struggle to balance sustainable farming with conservation at a beloved place. And like a fellow Lakeland farmer (and previous Wainwright Prize winner for English Pastoral), James Rebanks, he’s trying to be respectful of tradition while also restoring valuable habitats. My husband and I each took a library copy of Wild Fell along to Cumbria last week (about which more anon) and packed it in a backpack for an on-location photo during our wild walk at the very atmospheric Haweswater.

Where will your chain take you? Join us for #6Degrees of Separation! (Hosted on the first Saturday of each month by Kate W. of Books Are My Favourite and Best.) Next month’s starting book is Wifedom by Anna Funder.

Have you read any of my selections? Tempted by any you didn’t know before?

A Short Trip to Sedbergh, England’s Book Town

We’ve finally completed the ‘Triple Crown’ of British book towns: Hay-on-Wye in Wales is one of our favourite places and we’ve visited seven or more times over the years (the latest); inspired by Shaun Bythell’s memoirs, we then made the pilgrimage to Wigtown in Scotland in 2018. But we hadn’t made it to Sedbergh, England’s book town, until this past week. A short conference my husband was due to attend in the northwest of the country was the excuse we needed – though a medical emergency with our cat (fine now; just had to have an infected tooth out) shortened our trip and kept him from participating in the symposium at Lancaster.

Sedbergh is technically in Cumbria but falls within the Yorkshire Dales National Park. The book town initiative was part of a drive to re-invigorate the local economy after the 2001 foot and mouth disease outbreak. It’s a very sleepy town, more so than Hay or Wigtown, and only has two dedicated bookshops. The flagship store is Westwood Books, which was based in Hay until 2006 and occupies a former cinema / factory building. It is indeed reminiscent of Hay’s Cinema Bookshop, and is similar in size and stock to the largest of the Hay shops.

The only other shop in town that only sells books is Clutterbooks charity bookshop, where we started our book hunting after we left the car at our Airbnb flat on the Wednesday. With everything priced at £1 or £1.50, it tempted me into my first six purchases. Next up was Westwood, which opens until 5, an hour later than some other places. I bought a couple more books (delighted with the pristine secondhand copy of Julian Hoffman’s first nature book) but also resold them a small box of antiquarian and signed books for more than I could ever have hoped for – covering all my book purchases for the trip, as well as our meals and snacks out. On the Thursday we had a quiet drink in a cosy local pub to toast Her Majesty’s memory.

Various main street eateries and shops have a shelf or two of books for sale. We perused these, and the Little Free Library in the old bus shelter, on the Wednesday afternoon and first thing Friday morning. I added one more purchase to my stack – a paperback copy of Fire on the Mountain by Jean McNeil for £1 – just before we left town. In general, there weren’t as many bookshops as expected, and lots of places opened later or closed earlier than advertised, presumably because it was off season and rather rainy. So, it was a little underwhelming as book town experiences go, and I can’t imagine Sedbergh ever drawing us back.

However, we enjoyed exploring the area in general, with stops at Little Moreton Hall, and Sizergh Castle and Chester, respectively, on the way up and back. As part of the conference, we joined in a walk from Grange to Cartmel that took in an interesting limestone pavement landscape. It was my first time in the Dales or Lake District in many a year, and a good chance to get back to that pocket of the world.

Narcissism for Beginners by Martine McDonagh

Don’t talk like we were stuck in a lift.

Why would I be missing you so violently?

We’re all the hero when directing the scene,

But therapy for liars is a giant ice cream.

(from “Montparnasse” by Elbow)

I broke one of my cardinal reviewing rules—write about the book while it’s still fresh in your mind—and waited two weeks after finishing Martine McDonagh’s Narcissism for Beginners before writing it up. Luckily the Elbow stanza above (Guy Garvey’s lyrics are like poetry, after all) brought back to me some of the themes I want to explore: how you can miss someone you barely know, the way that ties ebb and shift such that your blood kin are strangers and the unrelated become like family, and how a narcissistic personality can use coercion and deception to get his or her way. Plus there’s the ice cream metaphor of the last line, a link to the terrific cover on finished copies of the novel—not on my proof, alas.

The novel is presented as Sonny Anderson’s extended letter to the mother he doesn’t remember. He’s lived with his guardian, a Brit named Thomas Hardiker, in Redondo Beach, California for 11 years; before that they were in Brazil with Sonny’s father. A month ago, on his twenty-first birthday, Sonny received the astounding news that he’s a millionaire thanks to a trust fund from his late father, Robin Agelaste-Bim, better known as Guru Bim. His mother is Sarah Anderson: once a Scottish housewife, now untraceable. Despite his youth, Sonny has been a meth addict and kicked the habit through NA. This kid’s done a lot of living already, but sets out on a new adventure to learn about his parents from those who knew them. And while he’s in Britain, he’ll squeeze in some tourism related to his favorite movie, Shaun of the Dead.

The novel is presented as Sonny Anderson’s extended letter to the mother he doesn’t remember. He’s lived with his guardian, a Brit named Thomas Hardiker, in Redondo Beach, California for 11 years; before that they were in Brazil with Sonny’s father. A month ago, on his twenty-first birthday, Sonny received the astounding news that he’s a millionaire thanks to a trust fund from his late father, Robin Agelaste-Bim, better known as Guru Bim. His mother is Sarah Anderson: once a Scottish housewife, now untraceable. Despite his youth, Sonny has been a meth addict and kicked the habit through NA. This kid’s done a lot of living already, but sets out on a new adventure to learn about his parents from those who knew them. And while he’s in Britain, he’ll squeeze in some tourism related to his favorite movie, Shaun of the Dead.

Starting with Sonny’s plane ride to Heathrow, the book is in the present tense, which makes you feel you’re taking the journey right along with him. Although this isn’t being marketed as young adult fiction, it has the same vibe as some YA quest narratives I’ve read: John Green’s The Fault in Our Stars, both of David Arnold’s books, and Nicola Yoon’s The Sun is Also a Star. Sonny is more bitter and world-weary than those teen protagonists, but you still get the slang and the pop culture references along with the heartfelt emotions.

Sonny’s first visit is to Torquay octogenarian Doris Henry, who was the Agelaste-Bims’ servant and Robin’s wet nurse circa 1970. Next up: London and Ruth Williams, whom Sonny’s mother, then going by Suki, recruited into a LifeForce meditation group. Ruth remembers taking against Guru Bim immediately: “He was faking it to get in with Suki. I understood the attraction, though; those narcissistic types are always charming.” Bim and Suki formed a splinter group, Trembling Leaves and soon announced Suki’s pregnancy, but things went awry and Suki fled to Scotland with her ex-boyfriend, Andrew.

This slightly madcap biographical trip around Britain also takes in Brighton, Scotland and Keswick in the Lake District. At each stop Sonny’s able to fill in more about his past, but it’s the letters Thomas sent along for him that contain the real shockers. It’s an epistolary within an epistolary, really, with Thomas’s series of long, explanatory letters daubing in the details and anchoring Sonny’s sometimes-earnest, sometimes-angry missive to his mother.

I loved tagging along on this kooky hero’s quest. My one small criticism about an otherwise zippy novel is that there is a lot of backstory to absorb, from Sonny’s former drug use onwards. For an American expat, though, it was especially fun to watch Sonny trying to get used to some peculiarities of Britain: “apparently it’s compulsory to eat potato chips and on Brit trains” and “We argue about which floor she lives on. I say second and Ruth says first, until we realise we mean the same thing.”

In a year that opened with a narcissist being installed in the White House and will soon see the publication of a new book about cult leader Jim Jones (The Road to Jonestown by Jeff Guinn, April 11th), McDonagh’s picture of Guru Bim is sure to strike a chord. As Ruth tells Sonny, in Ancient Greek an agelast was someone with no sense of humor; and she accused Bim of being “a manipulative charlatan.”

For Sonny, whose very name places him in relationship to others, coming to grips with who he came from means deciding to live differently and be content with his own piecemeal family, including Thomas, the Great Dudini (their dog), and maybe even a cool old lady like Ruth. You’ll love spending time with them all, and I imagine you’ll get a particular kick out of this if you like Shaun of the Dead. (Whisper it: I’ve never seen it.)

Narcissism for Beginners was published in the UK on March 9th. With thanks to Unbound for the review copy.

My rating:

Martine McDonagh was an artist manager in the music industry for 30 years and now leads the Creative Writing & Publishing MA at West Dean College, Sussex. This is her third novel, following I Have Waited, and You Have Come and After Phoenix.

Two favorites for me were “Formerly Feral,” in which a 13-year-old girl acquires a wolf as a stepsister and increasingly starts to resemble her; and the final, title story, a post-apocalyptic one in which a man and a pregnant woman are alone in a fishing boat, floating above a drowned world and living as if outside of time. This one is really rather terrifying. I also liked “Cassandra After,” in which a dead girlfriend comes back – it reminded me of Margaret Atwood’s The Robber Bride, which I’m currently reading for #MARM. “Stop Your Women’s Ears with Wax,” about a girl group experiencing Beatles-level fandom on a tour of the UK, felt like the odd one out to me in this collection.

Two favorites for me were “Formerly Feral,” in which a 13-year-old girl acquires a wolf as a stepsister and increasingly starts to resemble her; and the final, title story, a post-apocalyptic one in which a man and a pregnant woman are alone in a fishing boat, floating above a drowned world and living as if outside of time. This one is really rather terrifying. I also liked “Cassandra After,” in which a dead girlfriend comes back – it reminded me of Margaret Atwood’s The Robber Bride, which I’m currently reading for #MARM. “Stop Your Women’s Ears with Wax,” about a girl group experiencing Beatles-level fandom on a tour of the UK, felt like the odd one out to me in this collection. Sherwood alternates between Eva’s quest and a recreation of József’s time in wartorn Europe. Cleverly, she renders the past sections more immediate by writing them in the present tense, whereas Eva’s first-person narrative is in the past tense. Although József escaped the worst of the Holocaust by being sentenced to forced labor instead of going to a concentration camp, his brother László and their friend Zuzka were in Theresienstadt, so readers get a more complete picture of the Jewish experience at the time. All three wind up in the Lake District after the war, rebuilding their lives and making decisions that will affect future generations.

Sherwood alternates between Eva’s quest and a recreation of József’s time in wartorn Europe. Cleverly, she renders the past sections more immediate by writing them in the present tense, whereas Eva’s first-person narrative is in the past tense. Although József escaped the worst of the Holocaust by being sentenced to forced labor instead of going to a concentration camp, his brother László and their friend Zuzka were in Theresienstadt, so readers get a more complete picture of the Jewish experience at the time. All three wind up in the Lake District after the war, rebuilding their lives and making decisions that will affect future generations.