Three Days in June vs. Three Weeks in July

Two very good 2025 releases that I read from the library. While they could hardly be more different in tone and particulars, I couldn’t resist linking them via their titles.

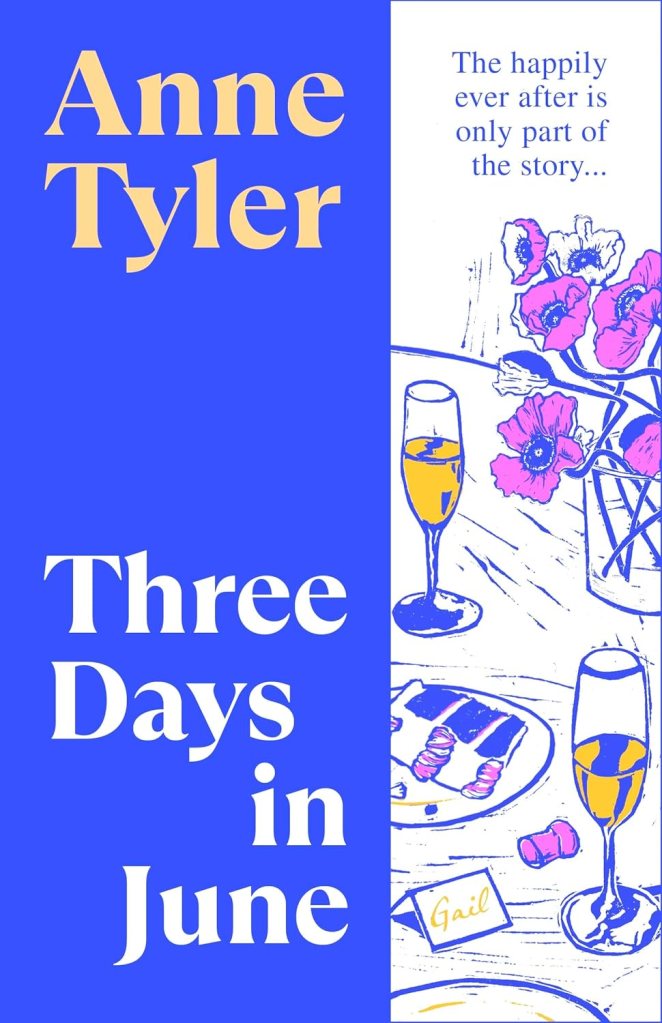

Three Days in June by Anne Tyler

(From my Most Anticipated list.) A delightful little book that I loved more than I expected to, for several reasons: the effective use of a wedding weekend as a way of examining what goes wrong in marriages and what we choose to live with versus what we can’t forgive; Gail’s first-person narration, a rarity for Tyler* and a decision that adds depth to what might otherwise have been a two-dimensional depiction of a woman whose people skills leave something to be desired; and the unexpected presence of a cat who brings warmth and caprice back into her home. (I read this soon after losing my old cat, and it was comforting to be reminded that cats and their funny ways are the same the world over.)

From Tyler’s oeuvre, this reminded me most of The Amateur Marriage and has a surprise Larry’s Party-esque ending. The discussion of the outmoded practice of tapping one’s watch is a neat tie-in to her recurring theme of the nature of time. And through the lunch out at a chic crab restaurant, she succeeds at making the Baltimore setting essential rather than incidental, more so than in much of her other work.

Gail is in the sandwich generation with a daughter just married and an old mother who’s just about independent. I appreciated that she’s 61 and contemplating retirement, but still feels as if she hasn’t a clue: “What was I supposed to do with the rest of my life? I’m too young for this, I thought. Not too old, as you might expect, but too young, too inept, too uninformed. How come there weren’t any grownups around? Why did everyone just assume I knew what I was doing?”

My only misgiving is that Tyler doesn’t quite get it right about the younger generation: women who are in their early thirties in 2023 (so born about 1990) wouldn’t be called Debbie and Bitsy. To some degree, Tyler’s still stuck back in the 1970s, but her observations about married couples and family dynamics are as shrewd as ever. Especially because of the novella length, I can recommend this to readers wanting to try Tyler for the first time. ![]()

*I’ve noted it in Earthly Possessions. Anywhere else?

Three Weeks in July: 7/7, The Aftermath, and the Deadly Manhunt by Adam Wishart and James Nally

July 7th is my wedding anniversary but before that, and ever since, it’s been known as the date of the UK’s worst terrorist attack, a sort of lesser 9/11 – and while reading this I felt the same way that I’ve felt reading books about 9/11: a sort of awed horror. Suicide bombers who were born in the UK but radicalized on trips to Islamic training camps in Pakistan set off explosions on three Underground trains and one London bus. I didn’t think my memories of 7/7 were strong, yet some names were incredibly familiar to me (chiefly Mohammad Sidique Khan, the leader of the attacks; Jean Charles de Menezes, the innocent Brazilian electrician shot dead on a Tube train when confused with a suspect in the 21/7 copycat plot – police were operating under a new shoot-to-kill policy and this was the tragic result).

Fifty-two people were killed that day, ranging in age from 20 to 60; 20 were not UK citizens, hailing from everywhere from Grenada to Mauritius. But a total of 770 people were injured. I found the authors’ recreation of events very gripping, though do be warned that there is a lot of gruesome medical and forensic detail about fatalities and injuries. They humanize the scale of events and make things personal by focusing on four individuals who were injured, even losing multiple limbs in some cases, but survived and now work in motivational speaking, disability services or survivor advocacy.

Fifty-two people were killed that day, ranging in age from 20 to 60; 20 were not UK citizens, hailing from everywhere from Grenada to Mauritius. But a total of 770 people were injured. I found the authors’ recreation of events very gripping, though do be warned that there is a lot of gruesome medical and forensic detail about fatalities and injuries. They humanize the scale of events and make things personal by focusing on four individuals who were injured, even losing multiple limbs in some cases, but survived and now work in motivational speaking, disability services or survivor advocacy.

What really got to me was thinking about all the hundreds of people who, 20 years on, still live with permanent pain, disability or grief because of the randomness of them or their loved ones getting caught up in a few misguided zealots’ plot. One detail that particularly struck me: with the Tube tunnels closed off at both ends while searchers recovered bodies, the temperature rose to 50 degrees C (122 degrees F), only exacerbating the stench. The book mostly avoids cliches and overwriting, though I did find myself skimming in places. It is based on the research done for a BBC documentary series and synthesizes a lot of material in an engaging way that does justice to the victims. ![]()

Have you read one or both of these?

Could you see yourself picking one of them up?

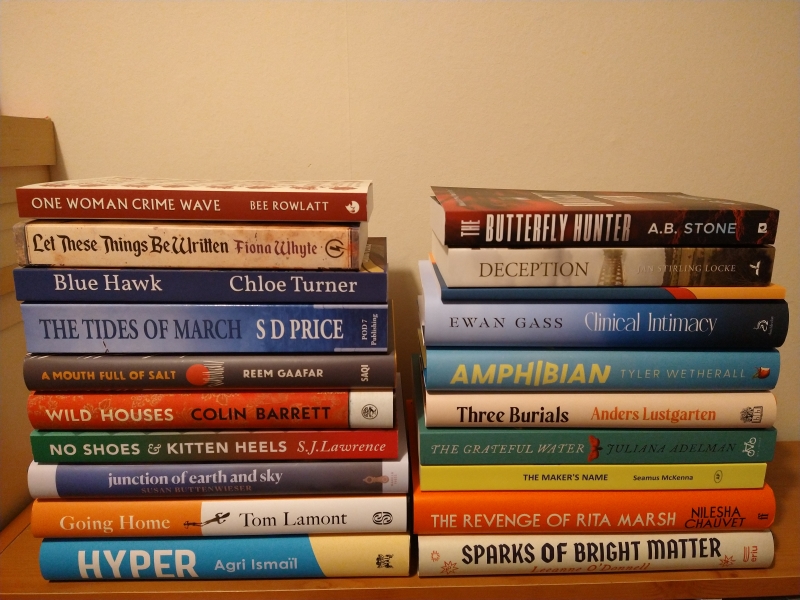

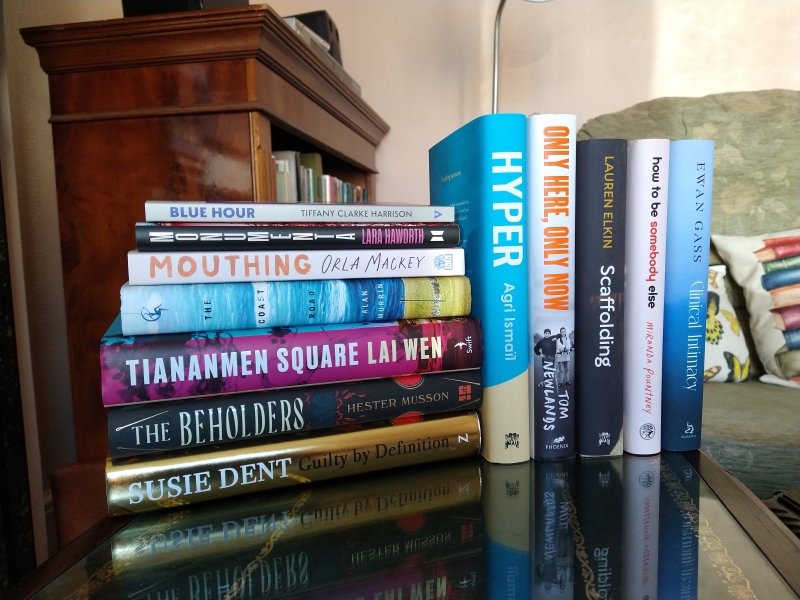

Etymology and Shakespeare studies are the keys to solving a cold case in Susie Dent’s clever, engrossing mystery, Guilty by Definition.

Etymology and Shakespeare studies are the keys to solving a cold case in Susie Dent’s clever, engrossing mystery, Guilty by Definition. Psychoanalysis, motherhood, and violence against women are resounding themes in Lauren Elkin’s Scaffolding. As history repeats itself one sweltering Paris summer, the personal and political structures undergirding the protagonists’ parallel lives come into question. This fearless, sophisticated work ponders what to salvage from the past—and what to tear down.

Psychoanalysis, motherhood, and violence against women are resounding themes in Lauren Elkin’s Scaffolding. As history repeats itself one sweltering Paris summer, the personal and political structures undergirding the protagonists’ parallel lives come into question. This fearless, sophisticated work ponders what to salvage from the past—and what to tear down. Clinical Intimacy’s mysterious antihero comes to life through interviews with his family, friends and clients. The brilliant oral history format builds a picture of isolation among vulnerable populations, only alleviated by care and touch—especially during Covid-19. Ewan Gass’s intricate story reminds us of the ultimate unknowability of other people.

Clinical Intimacy’s mysterious antihero comes to life through interviews with his family, friends and clients. The brilliant oral history format builds a picture of isolation among vulnerable populations, only alleviated by care and touch—especially during Covid-19. Ewan Gass’s intricate story reminds us of the ultimate unknowability of other people.

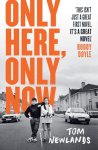

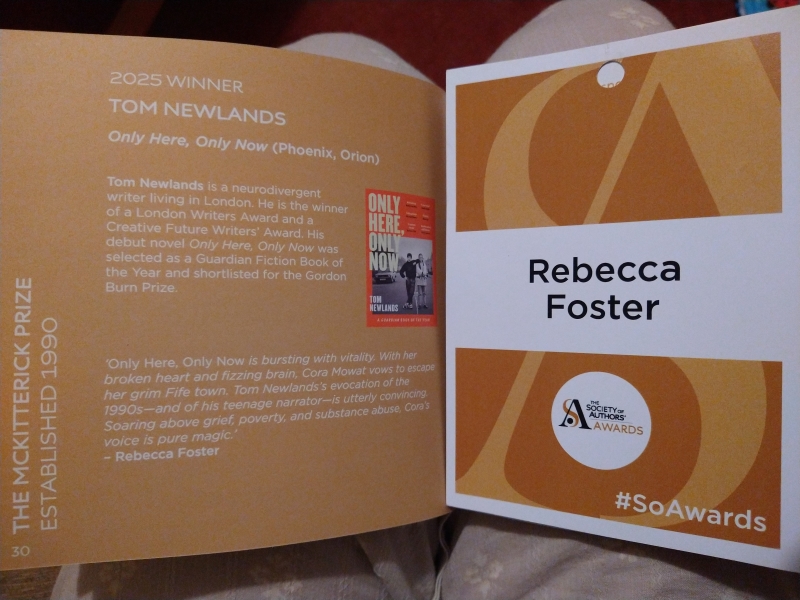

Only Here, Only Now is bursting with vitality. With her broken heart and fizzing brain, Cora Mowat vows to escape her grim Fife town. Tom Newlands’s evocation of the 1990s—and of his teenage narrator—is utterly convincing. Soaring above grief, poverty, and substance abuse, Cora’s voice is pure magic.

Only Here, Only Now is bursting with vitality. With her broken heart and fizzing brain, Cora Mowat vows to escape her grim Fife town. Tom Newlands’s evocation of the 1990s—and of his teenage narrator—is utterly convincing. Soaring above grief, poverty, and substance abuse, Cora’s voice is pure magic.

Hyper by Agri Ismaïl [I longlisted it – and then shortlisted it – but was outvoted]

Hyper by Agri Ismaïl [I longlisted it – and then shortlisted it – but was outvoted] How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney [It had two votes to make the shortlist, but because it was so similar to Scaffolding in its basics (a thirtysomething woman in a big city, the question of motherhood, and pregnancy loss) we decided to cut it.]

How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney [It had two votes to make the shortlist, but because it was so similar to Scaffolding in its basics (a thirtysomething woman in a big city, the question of motherhood, and pregnancy loss) we decided to cut it.]