Fairy Tales, Outlaws, Experimental Prose: Three More January Novels

Today I’m featuring three more works of fiction that were released this month, as a supplement to yesterday’s review of Mrs Death Misses Death. Although the four are hugely different in setting and style, and I liked some better than others (such is the nature of reading and book reviewing), together they’re further proof – as if we needed it – that female authors are pushing the envelope. I wouldn’t be surprised to see any or all of these on the Women’s Prize longlist in March.

The Charmed Wife by Olga Grushin

What happens next for Cinderella?

What happens next for Cinderella?

Grushin’s fourth novel unpicks a classic fairy tale narrative, starting 13.5 years into a marriage when, far from being starry-eyed with love for Prince Roland, the narrator hates her philandering husband and wants him dead. As she retells the Cinderella story to her children one bedtime, it only underscores how awry her own romance has gone: “my once-happy ending has proved to be only another beginning, a prelude to a tale dimmer, grittier, far more ambiguous, and far less suitable for children”. She gathers Roland’s hair and nails and goes to a witch for a spell, but her fairy godmother shows up to interfere. The two embark on a good cop/bad cop act as the princess runs backward through her memories: one defending Roland and the other convinced he’s a scoundrel.

Part One toggles back and forth between flashbacks (in the third person and past tense) and the present-day struggle for the narrator’s soul. She comes to acknowledge her own ignorance and bad behaviour. “All I want is to be free—free of him, free of my past, free of my story. Free of myself, the way I was when I was with him.” In Part Two, as the princess tries out different methods of escape, Grushin coyly inserts allusions to other legends and nursery rhymes: a stepsister lives with her many children in a house shaped like a shoe; the witch tells a variation on the Bluebeard story; the fairy godmother lives in a Hansel and Gretel-like candy cottage; the narrator becomes a maid for 12 slovenly sisters; and so on.

The plot feels fairly aimless in this second half, and the mixture of real-world and fantasy elements is peculiar. I much preferred Grushin’s previous book, Forty Rooms (and Angela Carter’s The Bloody Chamber, one of her chief inspirations). However, her two novels share a concern with how women’s ambitions can take a backseat to their roles, and both weave folktales and dreams into a picture of everyday life. But my favourite part of The Charmed Wife was the subplot: interludes about Brie and Nibbles, the princess’s pet mice; their lives being so much shorter, they run through many generations of a dramatic saga while the narrator (whose name we do finally learn, just a few pages from the end) is stuck in place.

The plot feels fairly aimless in this second half, and the mixture of real-world and fantasy elements is peculiar. I much preferred Grushin’s previous book, Forty Rooms (and Angela Carter’s The Bloody Chamber, one of her chief inspirations). However, her two novels share a concern with how women’s ambitions can take a backseat to their roles, and both weave folktales and dreams into a picture of everyday life. But my favourite part of The Charmed Wife was the subplot: interludes about Brie and Nibbles, the princess’s pet mice; their lives being so much shorter, they run through many generations of a dramatic saga while the narrator (whose name we do finally learn, just a few pages from the end) is stuck in place.

With thanks to Hodder & Stoughton for the free copy for review.

Outlawed by Anna North

I was a huge fan of North’s previous novel, The Life and Death of Sophie Stark, which cobbles together the story of the title character, a bisexual filmmaker, from accounts by the people who knew her best. Outlawed, an alternative history/speculative take on the traditional Western, could hardly be more different. In a subtly different version of the United States, everyone now alive in the 1890s is descended from those who survived a vicious 1830s flu epidemic. The duty to repopulate the nation has led to a cult of fertility and devotion to the Baby Jesus. From her mother, a midwife and herbalist, Ada has learned the basics of medical care, but the causes of barrenness remain a mystery and childlessness is perceived as a curse.

I was a huge fan of North’s previous novel, The Life and Death of Sophie Stark, which cobbles together the story of the title character, a bisexual filmmaker, from accounts by the people who knew her best. Outlawed, an alternative history/speculative take on the traditional Western, could hardly be more different. In a subtly different version of the United States, everyone now alive in the 1890s is descended from those who survived a vicious 1830s flu epidemic. The duty to repopulate the nation has led to a cult of fertility and devotion to the Baby Jesus. From her mother, a midwife and herbalist, Ada has learned the basics of medical care, but the causes of barrenness remain a mystery and childlessness is perceived as a curse.

Ada marries at 17 and fails to get pregnant within a year. After an acquaintance miscarries, rumours start to spread about Ada being a witch. Kicked out by her mother-in-law, she takes shelter first at a convent and then with the Hole in the Wall gang. She’ll be the doctor to this band of female outlaws who weren’t cut out for motherhood and shunned marriage – including lesbians, a mixed-race woman, and their leader, the Kid, who is nonbinary. The Kid is a mentally tortured prophet with a vision of making the world safe for people like them (“we were told a lie about God and what He wants from us”), mainly by, Robin Hood-like, redistributing wealth through hold-ups and bank robberies. Ada, who longs to conduct proper research into reproductive health rather than relying on religious propaganda, falls for another gender nonconformist, Lark, and does what she can to make the Kid’s dream a reality.

Reese Witherspoon choosing this for her Hello Sunshine book club was a great chance for North’s work to get more attention. However, I felt that the ideas behind this novel were more noteworthy than the execution. The similarity to The Handmaid’s Tale is undeniable, though I liked this a bit more. I most enjoyed the medical and religious themes, and appreciated the attention to childless and otherwise unconventional women. But the setup is so condensed and the consequences of the gang’s major heist so rushed that I wondered if the novel needed another 100 pages to stretch its wings. I’ll just have to await North’s next book.

With thanks to W&N for the proof copy for review.

little scratch by Rebecca Watson

I love a circadian narrative and had heard interesting things about the experimental style used in this debut novel. I even heard Watson read a passage from it as part of the Faber Live Fiction Showcase and found it very funny and engaging. But I really should have tried an excerpt before requesting this for review; I would have seen at a glance that it wasn’t for me. I don’t have a problem with prose being formatted like poetry (Girl, Woman, Other; Stubborn Archivist; the prologue of Wendy McGrath’s Santa Rosa; parts of Mrs Death Misses Death), but here it seemed to me that it was only done to alleviate the tedium of the contents.

I love a circadian narrative and had heard interesting things about the experimental style used in this debut novel. I even heard Watson read a passage from it as part of the Faber Live Fiction Showcase and found it very funny and engaging. But I really should have tried an excerpt before requesting this for review; I would have seen at a glance that it wasn’t for me. I don’t have a problem with prose being formatted like poetry (Girl, Woman, Other; Stubborn Archivist; the prologue of Wendy McGrath’s Santa Rosa; parts of Mrs Death Misses Death), but here it seemed to me that it was only done to alleviate the tedium of the contents.

A young woman who, like Watson, works for a newspaper, trudges through a typical day: wake up, get ready, commute to the office, waste time and snack in between doing bits of work, get outraged about inconsequential things, think about her boyfriend (only ever referred to as “my him” – probably my biggest specific pet peeve about the book), and push down memories of a sexual assault. Thus, the only thing that really happens happened before the book even started. Her scratching, to the point of open wounds and scabs, seems like a psychosomatic symptom of unprocessed trauma. By the end, she’s getting ready to tell her boyfriend about the assault, which seems like a step in the right direction.

I might have found Watson’s approach captivating in a short story, or as brief passages studded in a longer narrative. At first it’s a fun puzzle to ponder how these mostly unpunctuated words, dotted around the pages in two to six columns, fit together – should one read down each column, or across each row, or both? – but when all the scattershot words are only there to describe a train carriage filling up or repetitive quotidian actions (sifting through e-mails, pedalling a bicycle), the style soon grates. You may have more patience with it than I did if you loved A Girl Is a Half-Formed Thing or books by Emma Glass.

A favourite passage: “got to do this thing again, the waking up thing, the day thing, the work thing, disentangling from my duvet thing, this is something, this is a thing I have to do then,” [appears all as one left-aligned paragraph]

With thanks to Faber & Faber for the free copy for review.

Tomorrow I’ll review three nonfiction works published in January, all on a medical theme.

What recent releases can you recommend?

Recent Reviews for Shiny New Books: Poetry, Fiction and Nature Writing

First up was a rundown of my five favorite poetry releases of the year, starting with…

Dearly by Margaret Atwood

Dearly is a treasure trove, twice the length of the average poetry collection and rich with themes of memory, women’s rights, environmental crisis, and bereavement. It is reflective and playful, melancholy and hopeful. I can highly recommend it, even to non-poetry readers, because it is led by its themes; although there are layers to explore, these poems are generally about what they say they’re about, and more material than abstract. Alliteration, repetition, internal and slant rhymes, and neologisms will delight language lovers and make the book one to experience aloud as well as on paper. Atwood’s imagery ranges from the Dutch masters to The Wizard of Oz. Her frame of reference is as wide as the array of fields she’s written in over the course of over half a century.

Dearly is a treasure trove, twice the length of the average poetry collection and rich with themes of memory, women’s rights, environmental crisis, and bereavement. It is reflective and playful, melancholy and hopeful. I can highly recommend it, even to non-poetry readers, because it is led by its themes; although there are layers to explore, these poems are generally about what they say they’re about, and more material than abstract. Alliteration, repetition, internal and slant rhymes, and neologisms will delight language lovers and make the book one to experience aloud as well as on paper. Atwood’s imagery ranges from the Dutch masters to The Wizard of Oz. Her frame of reference is as wide as the array of fields she’s written in over the course of over half a century.

I’ll let you read the whole article to discover my four runners-up. (They’ll also be appearing in my fiction & poetry best-of post next week.)

Next was one of my most anticipated reads of the second half of 2020. (I was drawn to it by Susan’s review.)

Artifact by Arlene Heyman

Lottie’s story is a case study of the feminist project to reconcile motherhood and career (in this case, scientific research). In the generic more than the scientific meaning of the word, the novel is indeed about artifacts – as in works by Doris Lessing, Penelope Lively and Carol Shields, the goal is to unearth the traces of a woman’s life. The long chapters are almost like discrete short stories. Heyman follows Lottie through years of schooling and menial jobs, through a broken marriage and a period of single parenthood, and into a new relationship. There were aspects of the writing that didn’t work for me and I found the book as a whole more intellectually noteworthy than engaging as a story. A piercing – if not notably subtle – story of women’s choices and limitations in the latter half of the twentieth century. I’d recommend it to fans of Forty Rooms and The Female Persuasion.

Lottie’s story is a case study of the feminist project to reconcile motherhood and career (in this case, scientific research). In the generic more than the scientific meaning of the word, the novel is indeed about artifacts – as in works by Doris Lessing, Penelope Lively and Carol Shields, the goal is to unearth the traces of a woman’s life. The long chapters are almost like discrete short stories. Heyman follows Lottie through years of schooling and menial jobs, through a broken marriage and a period of single parenthood, and into a new relationship. There were aspects of the writing that didn’t work for me and I found the book as a whole more intellectually noteworthy than engaging as a story. A piercing – if not notably subtle – story of women’s choices and limitations in the latter half of the twentieth century. I’d recommend it to fans of Forty Rooms and The Female Persuasion.

Finally, I contributed a dual review of two works of nature writing that would make perfect last-minute Christmas gifts for outdoorsy types and/or would be perfect bedside books for reading along with the English seasons into a new year.

The Stubborn Light of Things by Melissa Harrison

This collects five and a half years’ worth of Harrison’s monthly Nature Notebook columns for The Times. The book falls into two rough halves, “City” and “Country”: initially based in South London, Harrison moved to the Suffolk countryside in late 2017. In the grand tradition of Gilbert White, she records when she sees her firsts of a year. Often, she need look no further than her own home and garden. I appreciated how hands-on and practical she is: She’s always picking up dead animals to clean up and display the skeletons, and she never misses an opportunity to tell readers about ways they can create habitat for wildlife (e.g. bat and bird nest boxes that can be incorporated into buildings) and get involved in citizen science projects like moth recording.

This collects five and a half years’ worth of Harrison’s monthly Nature Notebook columns for The Times. The book falls into two rough halves, “City” and “Country”: initially based in South London, Harrison moved to the Suffolk countryside in late 2017. In the grand tradition of Gilbert White, she records when she sees her firsts of a year. Often, she need look no further than her own home and garden. I appreciated how hands-on and practical she is: She’s always picking up dead animals to clean up and display the skeletons, and she never misses an opportunity to tell readers about ways they can create habitat for wildlife (e.g. bat and bird nest boxes that can be incorporated into buildings) and get involved in citizen science projects like moth recording.

The book’s final two entries were set during the UK’s first COVID-19 lockdown in spring 2020 – a notably fine season. This inspired me to review it alongside…

The Consolation of Nature by Michael McCarthy, Jeremy Mynott and Peter Marren

A tripartite diary of the coronavirus spring kept by three veteran nature writers based in southern England (all of them familiar to me through their involvement with New Networks for Nature and its annual Nature Matters conferences). The entries, of a similar length to Harrison’s, are grouped into chronological chapters from 21 March to 31 May. While the authors focus in these 10 weeks on their wildlife sightings – red kites, kestrels, bluebells, fungal fairy rings and much more – they also log government advice and death tolls. They achieve an ideal balance between current events and the timelessness of nature, enjoyed all the more in 2020’s unprecedented spring because of a dearth of traffic noise.

A tripartite diary of the coronavirus spring kept by three veteran nature writers based in southern England (all of them familiar to me through their involvement with New Networks for Nature and its annual Nature Matters conferences). The entries, of a similar length to Harrison’s, are grouped into chronological chapters from 21 March to 31 May. While the authors focus in these 10 weeks on their wildlife sightings – red kites, kestrels, bluebells, fungal fairy rings and much more – they also log government advice and death tolls. They achieve an ideal balance between current events and the timelessness of nature, enjoyed all the more in 2020’s unprecedented spring because of a dearth of traffic noise.

Book Serendipity in the Final Months of 2020

I call it Book Serendipity when two or more books that I read at the same time or in quick succession have something pretty bizarre in common. Because I have so many books on the go at once (20+), I suppose I’m more prone to such incidents than some. I also list these occasional reading coincidences on Twitter. (Earlier incidents from the year are here, here, and here.)

- Eel fishing plays a role in First Love, Last Rites by Ian McEwan and The Gospel of the Eels by Patrik Svensson.

- A girl’s body is found in a canal in First Love, Last Rites by Ian McEwan and Carrying Fire and Water by Deirdre Shanahan.

- Curlews on covers by Angela Harding on two of the most anticipated nature books of the year, English Pastoral by James Rebanks and The Wild Silence by Raynor Winn (and both came out on September 3rd).

- Thanksgiving dinner scenes feature in 666 Charing Cross Road by Paul Magrs and Such a Fun Age by Kiley Reid.

- A gay couple has the one man’s mother temporarily staying on the couch in 666 Charing Cross Road by Paul Magrs and Memorial by Bryan Washington.

- I was reading two “The Gospel of…” titles at once, The Gospel of Eve by Rachel Mann and The Gospel of the Eels by Patrik Svensson (and I’d read a third earlier in the year, The Gospel of Trees by Apricot Irving).

- References to Dickens’s David Copperfield in The Cider House Rules by John Irving and Mudbound by Hillary Jordan.

- The main female character has three ex-husbands, and there’s mention of chin-tightening exercises, in The Idea of Perfection by Kate Grenville and The Pumpkin Eater by Penelope Mortimer.

- A Welsh hills setting in On the Red Hill by Mike Parker and Along Came a Llama by Ruth Janette Ruck.

- Rachel Carson and Silent Spring are mentioned in A Year on the Wing by Tim Dee, The Frayed Atlantic Edge by David Gange, English Pastoral by James Rebanks and The Gospel of the Eels by Patrik Svensson. SS was also an influence on Losing Eden by Lucy Jones, which I read earlier in the year.

- There’s nude posing for a painter or photographer in The Glass Hotel by Emily St. John Mandel, How to Be Both by Ali Smith, and Adults by Emma Jane Unsworth.

- A weird, watery landscape is the setting for The Swallowed Man by Edward Carey and Piranesi by Susanna Clarke.

- Bawdy flirting between a customer and a butcher in The Idea of Perfection by Kate Grenville and Just Like You by Nick Hornby.

- Corbels (an architectural term) mentioned in The Idea of Perfection by Kate Grenville and Wakenhyrst by Michelle Paver.

- Near or actual drownings (something I encounter FAR more often in fiction than in real life, just like both parents dying in a car crash) in The Idea of Perfection, The Glass Hotel, The Gospel of Eve, Wakenhyrst, and Love and Other Thought Experiments.

- Nematodes are mentioned in The Gospel of the Eels by Patrik Svensson and Real Life by Brandon Taylor.

- A toxic lake features in The New Wilderness by Diane Cook and Real Life by Brandon Taylor (both were also on the Booker Prize shortlist).

- A black scientist from Alabama is the main character in Transcendent Kingdom by Yaa Gyasi and Real Life by Brandon Taylor.

- Graduate studies in science at the University of Wisconsin, and rivals sabotaging experiments, in Artifact by Arlene Heyman and Real Life by Brandon Taylor.

- A female scientist who experiments on rodents in Transcendent Kingdom by Yaa Gyasi and Artifact by Arlene Heyman.

- There are poems about blackberrying in Dearly by Margaret Atwood, Passport to Here and There by Grace Nichols, and How to wear a skin by Louisa Adjoa Parker. (Nichols’s “Blackberrying Black Woman” actually opens with “Everyone has a blackberry poem. Why not this?” – !)

What’s the weirdest reading coincidence you’ve had lately?

November Plans: Novellas, Margaret Atwood Reading Month & More

My big thing next month will, of course, be Novellas in November, which I’m co-hosting with Cathy of 746 Books as a month-long challenge with four weekly prompts. I’m taking the lead on two alternating weeks and will introduce them with mini-reviews of some of my favorite short books from these categories:

9–15 November: Nonfiction novellas

23–29 November: Short classics

I’m also using this as an excuse to get back into the nine books of under 200 pages that have ended up on my “Set Aside Temporarily” shelf. I swore after last year that I would break myself of the bad habit of letting books linger like this, but it has continued in 2020.

Other November reading plans…

Readalong of Derek Jarman’s Modern Nature

I learned about this book through Losing Eden by Lucy Jones; she mentions it in the context of nature helping people come to terms with their mortality. Jarman found solace in his Dungeness, Kent garden while dying of AIDS. Shortly after I came across that reference, I learned that his home, Prospect Cottage, had just been rescued from private sale by a crowdfunding campaign. I hope to visit it someday. In the meantime, Creative Folkestone is hosting an Autumn Reads festival on his journal, Modern Nature, running from the 19th to 22nd. I’ve already begun reading it to get a headstart. Do you have a copy? If so, join in!

I learned about this book through Losing Eden by Lucy Jones; she mentions it in the context of nature helping people come to terms with their mortality. Jarman found solace in his Dungeness, Kent garden while dying of AIDS. Shortly after I came across that reference, I learned that his home, Prospect Cottage, had just been rescued from private sale by a crowdfunding campaign. I hope to visit it someday. In the meantime, Creative Folkestone is hosting an Autumn Reads festival on his journal, Modern Nature, running from the 19th to 22nd. I’ve already begun reading it to get a headstart. Do you have a copy? If so, join in!

Margaret Atwood Reading Month

This is the third year of #MARM, hosted by Canadian bloggers extraordinaires Marcie of Buried in Print and Naomi of Consumed by Ink. (Check out the neat bingo card they made this year!) I plan to read the short story volume Wilderness Tips and her new poetry collection, Dearly,on the way for me to review for Shiny New Books. If I fancy adding anything else in, there are tons of her books to choose from across the holdings of the public and university libraries.

This is the third year of #MARM, hosted by Canadian bloggers extraordinaires Marcie of Buried in Print and Naomi of Consumed by Ink. (Check out the neat bingo card they made this year!) I plan to read the short story volume Wilderness Tips and her new poetry collection, Dearly,on the way for me to review for Shiny New Books. If I fancy adding anything else in, there are tons of her books to choose from across the holdings of the public and university libraries.

Nonfiction November

I don’t usually participate in this challenge because nonfiction makes up at least 40% of my reading anyway, but the past couple of years I enjoyed putting together fiction and nonfiction pairings and “Being the Expert” on women’s religious memoirs. I might end up doing at least one post, especially as I have some “Three on a Theme” posts in mind to encompass a couple of nonfiction topics I happen to have read several books about. The full schedule is here.

Young Writer of the Year Award

Being on the shadow panel for the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award was a highlight of 2017 for me. I look forward to following along with the nominated books, as I did last year, and attending the virtual prize ceremony. With any luck I will already have read at least one or two books from the shortlist of four. Fingers crossed for Rowan Hisayo Buchanan, Naoise Dolan, Jessica J. Lee, Olivia Potts and Nina Mingya Powles; Niamh Campbell, Catherine Cho, Tiffany Francis and Emma Glass are a few other possibilities. (By chance, only young women are on my radar this year!)

Being on the shadow panel for the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award was a highlight of 2017 for me. I look forward to following along with the nominated books, as I did last year, and attending the virtual prize ceremony. With any luck I will already have read at least one or two books from the shortlist of four. Fingers crossed for Rowan Hisayo Buchanan, Naoise Dolan, Jessica J. Lee, Olivia Potts and Nina Mingya Powles; Niamh Campbell, Catherine Cho, Tiffany Francis and Emma Glass are a few other possibilities. (By chance, only young women are on my radar this year!)

November is such a busy month for book blogging: it’s also Australia Reading Month and German Literature Month. I don’t happen to have any books on the pile that will fit these prompts, but you might like to think about how you can combine one of them with some of the other challenges out there!

A debut trio of raw stories set in the Yorkshire countryside. In “Offcomers,” the 2001 foot and mouth disease outbreak threatens the happiness of a sheep-farming couple. The effects of rural isolation on a relationship resurface in “Outside Are the Dogs.” In “Cull Yaw,” a vegetarian gets involved with a butcher who’s keen on marketing mutton and ends up helping him with a grisly project. This was the stand-out for me. I appreciated the clear-eyed look at where food comes from. At the same time, narrator Star’s mother is ailing: a reminder that decay is inevitable and we are all naught but flesh and blood. I liked the prose well enough, but found the characterization a bit thin. One for readers of Andrew Michael Hurley and Cynan Jones. (See also

A debut trio of raw stories set in the Yorkshire countryside. In “Offcomers,” the 2001 foot and mouth disease outbreak threatens the happiness of a sheep-farming couple. The effects of rural isolation on a relationship resurface in “Outside Are the Dogs.” In “Cull Yaw,” a vegetarian gets involved with a butcher who’s keen on marketing mutton and ends up helping him with a grisly project. This was the stand-out for me. I appreciated the clear-eyed look at where food comes from. At the same time, narrator Star’s mother is ailing: a reminder that decay is inevitable and we are all naught but flesh and blood. I liked the prose well enough, but found the characterization a bit thin. One for readers of Andrew Michael Hurley and Cynan Jones. (See also  Okorie emigrated from Nigeria to Ireland in 2005. Her time living in a direct provision hostel for asylum seekers informed the title story about women queuing for and squabbling over food rations, written in an African pidgin. In “Under the Awning,” a Black woman fictionalizes her experiences of racism into a second-person short story her classmates deem too bleak. The Author’s Note reveals that Okorie based this one on comments she herself got in a writers’ group. “The Egg Broke” returns to Nigeria and its old superstition about twins.

Okorie emigrated from Nigeria to Ireland in 2005. Her time living in a direct provision hostel for asylum seekers informed the title story about women queuing for and squabbling over food rations, written in an African pidgin. In “Under the Awning,” a Black woman fictionalizes her experiences of racism into a second-person short story her classmates deem too bleak. The Author’s Note reveals that Okorie based this one on comments she herself got in a writers’ group. “The Egg Broke” returns to Nigeria and its old superstition about twins. This is the third time Simpson has made it into one of my September features (after

This is the third time Simpson has made it into one of my September features (after  I start with that bit of synopsis because Mother for Dinner showcases rather analogous situations and attitudes, but ultimately didn’t come together as successfully for me. It’s a satire on the immigrant and minority experience in the USA – the American dream of ‘melting pot’ assimilation that we see contradicted daily by tribalism and consumerism. Seventh Seltzer works in Manhattan publishing and has to vet identity stories vying to be the next Great American Novel: “The Heroin-Addicted-Autistic-Christian-American-Diabetic one” and “the Gender-Neutral-Albino-Lebanese-Eritrean-American” one are two examples. But Seventh is a would-be writer himself, compelled to tell the Cannibal-American story.

I start with that bit of synopsis because Mother for Dinner showcases rather analogous situations and attitudes, but ultimately didn’t come together as successfully for me. It’s a satire on the immigrant and minority experience in the USA – the American dream of ‘melting pot’ assimilation that we see contradicted daily by tribalism and consumerism. Seventh Seltzer works in Manhattan publishing and has to vet identity stories vying to be the next Great American Novel: “The Heroin-Addicted-Autistic-Christian-American-Diabetic one” and “the Gender-Neutral-Albino-Lebanese-Eritrean-American” one are two examples. But Seventh is a would-be writer himself, compelled to tell the Cannibal-American story.

There is dramatic irony here between what the characters know about each other and what we, the readers, know – echoed by what “we,” the church Mothers, observe in the first-person plural sections that open most chapters. I love the use of a Greek chorus to comment on a novel’s action, and The Mothers reminded me of the elderly widows in the Black church I grew up attending. (I watched the video of a wedding that took place there early this month and there they were, perched on aisle seats in their prim purple suits and matching hats.)

There is dramatic irony here between what the characters know about each other and what we, the readers, know – echoed by what “we,” the church Mothers, observe in the first-person plural sections that open most chapters. I love the use of a Greek chorus to comment on a novel’s action, and The Mothers reminded me of the elderly widows in the Black church I grew up attending. (I watched the video of a wedding that took place there early this month and there they were, perched on aisle seats in their prim purple suits and matching hats.) I particularly liked “The Pangs of Love” by Jane Gardam, a retelling of the Hans Christian Andersen fairy tale of “The Little Mermaid,” and “Swans” by Janet Frame, in which a mother takes her two little girls for a cheeky weekday trip to the beach. Fay and Totty are dismayed to learn that their mother is fallible: she chose the wrong beach, one without amenities, and can’t guarantee that all will be well on their return. A dusky lagoon full of black swans is an alluring image of peace, quickly negated by the unpleasant scene that greets them at home.

I particularly liked “The Pangs of Love” by Jane Gardam, a retelling of the Hans Christian Andersen fairy tale of “The Little Mermaid,” and “Swans” by Janet Frame, in which a mother takes her two little girls for a cheeky weekday trip to the beach. Fay and Totty are dismayed to learn that their mother is fallible: she chose the wrong beach, one without amenities, and can’t guarantee that all will be well on their return. A dusky lagoon full of black swans is an alluring image of peace, quickly negated by the unpleasant scene that greets them at home.

Passport to Here and There by Grace Nichols: Nichols’s ninth collection is split, like her identity, between the Guyana where she grew up and the England which she has made her home. Creole and the imagery of ghosts conjure up her coming of age in South America. She often draws on the natural world for her metaphors, and her style is characterized by alliteration and assonance. Nichols brings her adopted country to life with poems on everything from tea and the Thames to the London Underground and the Grenfell Tower fire. (My full review will appear in Issue 106 of Wasafiri literary magazine.)

Passport to Here and There by Grace Nichols: Nichols’s ninth collection is split, like her identity, between the Guyana where she grew up and the England which she has made her home. Creole and the imagery of ghosts conjure up her coming of age in South America. She often draws on the natural world for her metaphors, and her style is characterized by alliteration and assonance. Nichols brings her adopted country to life with poems on everything from tea and the Thames to the London Underground and the Grenfell Tower fire. (My full review will appear in Issue 106 of Wasafiri literary magazine.)

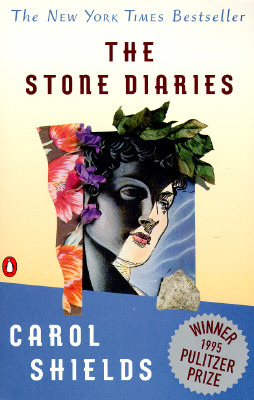

The facts are these. Daisy’s mother, Mercy, dies giving birth to her in rural Manitoba. Raised by a neighbor, Daisy later moves to Indiana with her stonecutter father, Cuyler. After a disastrously short first marriage, Daisy returns to Canada to marry Barker Flett. Their three children and Ottawa garden become her life. She temporarily finds purpose in her empty-nest years by writing a “Mrs. Green Thumb” column for a local newspaper, but her retirement in Florida is plagued by illness and the feeling that she has missed out on what matters most.

The facts are these. Daisy’s mother, Mercy, dies giving birth to her in rural Manitoba. Raised by a neighbor, Daisy later moves to Indiana with her stonecutter father, Cuyler. After a disastrously short first marriage, Daisy returns to Canada to marry Barker Flett. Their three children and Ottawa garden become her life. She temporarily finds purpose in her empty-nest years by writing a “Mrs. Green Thumb” column for a local newspaper, but her retirement in Florida is plagued by illness and the feeling that she has missed out on what matters most. As in Moon Tiger, one of my absolute favorites, the author explores how events and memories turn into artifacts. The meta approach also, I suspect, tips the hat to other works of Canadian literature: in her introduction, Margaret Atwood mentions that the poet whose story inspired Shields’s Mary Swann had a collection entitled A Stone Diary, and surely the title’s similarity to Margaret Laurence’s

As in Moon Tiger, one of my absolute favorites, the author explores how events and memories turn into artifacts. The meta approach also, I suspect, tips the hat to other works of Canadian literature: in her introduction, Margaret Atwood mentions that the poet whose story inspired Shields’s Mary Swann had a collection entitled A Stone Diary, and surely the title’s similarity to Margaret Laurence’s

The Booker ceremony was nicely tailored to viewers at home, incorporating brief, informal pre-recorded interviews with each nominated author and a video chat between last year’s winners, Margaret Atwood and Bernardine Evaristo. When Evaristo asked Atwood about the difference between winning the Booker in 2019 versus in 2000, she replied, deadpan, “I was older.” I especially liked the short monologues that well-known UK actors performed from each shortlisted book. Only a few people – the presenter, Evaristo, chair of judges and publisher Margaret Busby, and a string quartet – appeared in the studio, while all the other participants beamed in from other times and places. Stuart is only the second Scottish winner of the Booker, and seemed genuinely touched for this recognition of his tribute to his mother.

The Booker ceremony was nicely tailored to viewers at home, incorporating brief, informal pre-recorded interviews with each nominated author and a video chat between last year’s winners, Margaret Atwood and Bernardine Evaristo. When Evaristo asked Atwood about the difference between winning the Booker in 2019 versus in 2000, she replied, deadpan, “I was older.” I especially liked the short monologues that well-known UK actors performed from each shortlisted book. Only a few people – the presenter, Evaristo, chair of judges and publisher Margaret Busby, and a string quartet – appeared in the studio, while all the other participants beamed in from other times and places. Stuart is only the second Scottish winner of the Booker, and seemed genuinely touched for this recognition of his tribute to his mother.

Back on 18 November, I attended another online event to which I’d gotten a last-minute invitation: a “book club” featuring Tracy Chevalier in conversation with her literary agent, Jonny Geller, on Girl with a Pearl Earring at 20 and her new novel, A Single Thread. In 1996 she sent Geller a letter asking if he’d read Virgin Blue, which she’d written for the MA at the University of East Anglia – the only UK Creative Writing course out there at the time. After VB, she started a contemporary novel set at Highgate Cemetery, where she was a tour guide. It was to be called Live a Little (since a Howard Jacobson title). But shortly thereafter, she was lying in bed one day, looking at a Vermeer print on the wall, and asked herself what the look on the girl’s face meant and who she was. She sent Geller one page of thoughts and he immediately told her to stick Live a Little in a drawer and focus on the Vermeer idea.

Back on 18 November, I attended another online event to which I’d gotten a last-minute invitation: a “book club” featuring Tracy Chevalier in conversation with her literary agent, Jonny Geller, on Girl with a Pearl Earring at 20 and her new novel, A Single Thread. In 1996 she sent Geller a letter asking if he’d read Virgin Blue, which she’d written for the MA at the University of East Anglia – the only UK Creative Writing course out there at the time. After VB, she started a contemporary novel set at Highgate Cemetery, where she was a tour guide. It was to be called Live a Little (since a Howard Jacobson title). But shortly thereafter, she was lying in bed one day, looking at a Vermeer print on the wall, and asked herself what the look on the girl’s face meant and who she was. She sent Geller one page of thoughts and he immediately told her to stick Live a Little in a drawer and focus on the Vermeer idea.

Lastly, Chevalier and Geller talked about her new novel, A Single Thread, which was conceived before Trump and Brexit but had its central themes reinforced by the constant references back to 1930s fascism during the Trump presidency. She showed off the needlepoint spectacles case she’d embroidered for the novel. This wasn’t the first time she’d taken up a craft featured in her fiction: for The Last Runaway she learned to quilt, and indeed still quilts today. Geller likened her to a “method actor,” and jokingly fretted that they’ll lose her to one of these hobbies one day. Chevalier’s work in progress features Venetian glass. I’m already looking forward to it.

Lastly, Chevalier and Geller talked about her new novel, A Single Thread, which was conceived before Trump and Brexit but had its central themes reinforced by the constant references back to 1930s fascism during the Trump presidency. She showed off the needlepoint spectacles case she’d embroidered for the novel. This wasn’t the first time she’d taken up a craft featured in her fiction: for The Last Runaway she learned to quilt, and indeed still quilts today. Geller likened her to a “method actor,” and jokingly fretted that they’ll lose her to one of these hobbies one day. Chevalier’s work in progress features Venetian glass. I’m already looking forward to it.

If pressed to give a one-line summary, I would say the overall theme of this collection is the power that women have (or do not have) in relationships – this is often a question of sex, but not always. Much of the collection falls neatly into pairs: “True Trash” and “Death by Landscape” are about summer camp and the effects that experiences had there still have decades later; “The Bog Man” and “The Age of Lead” both use the discovery of a preserved corpse (one a bog body, the other a member of the Franklin Expedition) as a metaphor for a frozen relationship; and “Hairball” and “Weight” are about a mistress’s power plays. I actually made myself a key on the table of contents page, assigning A, B, and C to those topics. The title story I labeled [A/C] because it’s set at a family’s lake house but the foreign spouse of one of the sisters has history with or designs on all three.

If pressed to give a one-line summary, I would say the overall theme of this collection is the power that women have (or do not have) in relationships – this is often a question of sex, but not always. Much of the collection falls neatly into pairs: “True Trash” and “Death by Landscape” are about summer camp and the effects that experiences had there still have decades later; “The Bog Man” and “The Age of Lead” both use the discovery of a preserved corpse (one a bog body, the other a member of the Franklin Expedition) as a metaphor for a frozen relationship; and “Hairball” and “Weight” are about a mistress’s power plays. I actually made myself a key on the table of contents page, assigning A, B, and C to those topics. The title story I labeled [A/C] because it’s set at a family’s lake house but the foreign spouse of one of the sisters has history with or designs on all three. To open the afternoon program, Dr. Fiona Tolan of Liverpool John Moores University spoke on “21st-century Gileads: Feminist Dystopian Fiction after Atwood.” She noted that The Handmaid’s Tale casts a long shadow; it’s entered into our cultural lexicon and isn’t going anywhere. She showed covers of three fairly recent books that take up the Handmaid’s red: The Power, Vox, and Red Clocks. However, the two novels she chose to focus on do not have comparable covers: The Water Cure by Sophie Mackintosh (

To open the afternoon program, Dr. Fiona Tolan of Liverpool John Moores University spoke on “21st-century Gileads: Feminist Dystopian Fiction after Atwood.” She noted that The Handmaid’s Tale casts a long shadow; it’s entered into our cultural lexicon and isn’t going anywhere. She showed covers of three fairly recent books that take up the Handmaid’s red: The Power, Vox, and Red Clocks. However, the two novels she chose to focus on do not have comparable covers: The Water Cure by Sophie Mackintosh (