April Releases by Chung, Ellis, Gaige, Lutz, McAlpine and Rubin

April felt like a crowded publishing month, though May looks to be twice as busy again. Adding this batch to my existing responses to books by Jean Hannah Edelstein & Emily Jungmin Yoon plus Richard Scott, I reviewed nine April releases. Today I’m featuring a real mix of books by women, starting with two foodie family memoirs, moving through a suspenseful novel about a lost hiker, a sparse Scandinavian novella, and a lovely poetry collection with themes of nature and family, and finishing up with a collection of aphorisms. I challenged myself to write just a paragraph on each for simplicity and readability.

Chinese Parents Don’t Say I Love You: A memoir of saying the unsayable with food by Candice Chung

“to love is to gamble, sometimes gastrointestinally … The stomach is a simple animal. But how do we settle the heart—a flailing, skittish thing?”

I got Caroline Eden (Cold Kitchen) and Nina Mingya Powles (Tiny Moons) vibes from this vibrant essay collection spotlighting food and family. The focus is on 2019–2021, a time of huge changes for Chung. She’s from Hong Kong via Australia, and reconnects with her semi-estranged parents by taking them along on restaurant review gigs for a Sydney newspaper. Fresh from a 13-year relationship with “the psychic reader,” she starts dating again and quickly falls in deep with “the geographer.” Sharing meals in restaurants and at home kindles closeness and keeps their spirits up after Covid restrictions descend. But when he gets a job offer in Scotland, they have to make decisions about their relationship sooner than intended. Although there is a chronological through line, the essays range in time and style, including second-person advice column (“Faux Pas”) and choose-your-own adventure (“Self-Help Meal”) segments alongside lists, message threads and quotes from the likes of Deborah Levy. My favourite piece was “The Soup at the End of the Universe.” Chung delicately contrasts past and present, singleness and being partnered, and different mental health states. The essays meld to capture a life in transition and the tastes and bonds that don’t alter.

I got Caroline Eden (Cold Kitchen) and Nina Mingya Powles (Tiny Moons) vibes from this vibrant essay collection spotlighting food and family. The focus is on 2019–2021, a time of huge changes for Chung. She’s from Hong Kong via Australia, and reconnects with her semi-estranged parents by taking them along on restaurant review gigs for a Sydney newspaper. Fresh from a 13-year relationship with “the psychic reader,” she starts dating again and quickly falls in deep with “the geographer.” Sharing meals in restaurants and at home kindles closeness and keeps their spirits up after Covid restrictions descend. But when he gets a job offer in Scotland, they have to make decisions about their relationship sooner than intended. Although there is a chronological through line, the essays range in time and style, including second-person advice column (“Faux Pas”) and choose-your-own adventure (“Self-Help Meal”) segments alongside lists, message threads and quotes from the likes of Deborah Levy. My favourite piece was “The Soup at the End of the Universe.” Chung delicately contrasts past and present, singleness and being partnered, and different mental health states. The essays meld to capture a life in transition and the tastes and bonds that don’t alter.

With thanks to Elliott & Thompson for the free copy for review.

Chopping Onions on My Heart: On Losing and Preserving Culture by Samantha Ellis

Ellis was distressed to learn that her refugee parents’ first language, Judeo-Iraqi Arabic, is in danger of extinction. Her own knowledge of it is piecemeal, mostly confined to its colourful food-inspired sayings – for example, living “eeyam al babenjan (in the days of the aubergines)” means that everything feels febrile and topsy-turvy. She recounts her family’s history with conflict and displacement, takes a Zoom language class, and ponders what words, dishes, and objects she would save on an imaginary “ark” that she hopes to bequeath to her son. Along the way, she reveals surprising facts about Ashkenazi domination of the Jewish narrative. “Did you know the poet [Siegfried Sassoon] was an Iraqi Jew?” His great-grandfather even invented a special variety of mango pickle. All of the foods described sound delicious, and some recipes are given. Ellis’s writing is enthusiastic and she braids the book’s various strands effectively. I wasn’t as interested in the niche history as I wanted to be, but I did appreciate learning about an endangered culture and language.

Ellis was distressed to learn that her refugee parents’ first language, Judeo-Iraqi Arabic, is in danger of extinction. Her own knowledge of it is piecemeal, mostly confined to its colourful food-inspired sayings – for example, living “eeyam al babenjan (in the days of the aubergines)” means that everything feels febrile and topsy-turvy. She recounts her family’s history with conflict and displacement, takes a Zoom language class, and ponders what words, dishes, and objects she would save on an imaginary “ark” that she hopes to bequeath to her son. Along the way, she reveals surprising facts about Ashkenazi domination of the Jewish narrative. “Did you know the poet [Siegfried Sassoon] was an Iraqi Jew?” His great-grandfather even invented a special variety of mango pickle. All of the foods described sound delicious, and some recipes are given. Ellis’s writing is enthusiastic and she braids the book’s various strands effectively. I wasn’t as interested in the niche history as I wanted to be, but I did appreciate learning about an endangered culture and language.

With thanks to Chatto & Windus (Vintage/Penguin) for the proof copy for review.

Heartwood by Amity Gaige

This was on my Most Anticipated list after how much I’d enjoyed Sea Wife when we read it for Literary Wives club. In July 2022, 42-year-old nurse Valerie Gillis, nicknamed “Sparrow,” goes missing in the Maine woods while hiking the Appalachian Trail. An increasingly desperate search ensues as the chances of finding her alive diminish with each day. The shifting formats – letters, transcripts, news reports, tip line messages – hold the interest. However, the chapters voiced by Lt. Bev, the warden who heads the mission, are much the most engaging, and it’s a shame that her delightful interactions with her sisters and nieces are so few and come so late. The third-person passages about Lena Kucharski in her Connecticut retirement home are intriguing but somehow feel like they belong in a different book. Gaige attempts to bring the threads together through three mother–daughter pairs, which struck me as heavy-handed. Mostly, this hits the sweet spot between mystery and literary fiction (apart from some red herrings), but because I wasn’t particularly invested in the characters, even Valerie, this fell a little short of my expectations. (Read via Edelweiss)

This was on my Most Anticipated list after how much I’d enjoyed Sea Wife when we read it for Literary Wives club. In July 2022, 42-year-old nurse Valerie Gillis, nicknamed “Sparrow,” goes missing in the Maine woods while hiking the Appalachian Trail. An increasingly desperate search ensues as the chances of finding her alive diminish with each day. The shifting formats – letters, transcripts, news reports, tip line messages – hold the interest. However, the chapters voiced by Lt. Bev, the warden who heads the mission, are much the most engaging, and it’s a shame that her delightful interactions with her sisters and nieces are so few and come so late. The third-person passages about Lena Kucharski in her Connecticut retirement home are intriguing but somehow feel like they belong in a different book. Gaige attempts to bring the threads together through three mother–daughter pairs, which struck me as heavy-handed. Mostly, this hits the sweet spot between mystery and literary fiction (apart from some red herrings), but because I wasn’t particularly invested in the characters, even Valerie, this fell a little short of my expectations. (Read via Edelweiss)

Wild Boar by Hannah Lutz (2016; 2025)

[Translated from Swedish by Andy Turner]

“I have seen them, the wild boar, they have found their way into my dreams!” Ritve travels from Finland to the forests of southern Sweden to track the creatures. Glenn, who appraises project applications for the council, has boar wander onto his property in the middle of the night. Mia, recipient of a council grant for her Recollections of a Sigga Child proposal, brings her ailing grandfather to record his memories for the local sound archive. As midsummer approaches, these three characters plus a couple of their partners will have encounters with the boar and with each other. Short sections alternate between their first-person perspectives. There is a strong sense of place and how migration poses challenges for both the human and more-than-human worlds. But it’s over before it begins. I found myself frustrated by how little happens, how stingily the characters reveal themselves, and how the boar, ultimately, are no more than a metaphor or plot device – a frequent complaint of mine when animals are central to a narrative. This might appeal to fans of Melissa Harrison’s fiction. In any case, I congratulate The Emma Press on their first novel, which won an English PEN Award.

“I have seen them, the wild boar, they have found their way into my dreams!” Ritve travels from Finland to the forests of southern Sweden to track the creatures. Glenn, who appraises project applications for the council, has boar wander onto his property in the middle of the night. Mia, recipient of a council grant for her Recollections of a Sigga Child proposal, brings her ailing grandfather to record his memories for the local sound archive. As midsummer approaches, these three characters plus a couple of their partners will have encounters with the boar and with each other. Short sections alternate between their first-person perspectives. There is a strong sense of place and how migration poses challenges for both the human and more-than-human worlds. But it’s over before it begins. I found myself frustrated by how little happens, how stingily the characters reveal themselves, and how the boar, ultimately, are no more than a metaphor or plot device – a frequent complaint of mine when animals are central to a narrative. This might appeal to fans of Melissa Harrison’s fiction. In any case, I congratulate The Emma Press on their first novel, which won an English PEN Award.

With thanks to The Emma Press for the free copy for review.

Small Pointed Things by Erica McAlpine

McAlpine is an associate professor of English at Oxford. Her second poetry collection is full of flora and fauna imagery. The title phrase comes from the opening poem, “Bats and Swallows” – in the “gloaming,” it’s hard to tell the difference between the flying creatures. The verse is bursting with alliteration and end rhymes, as just this first one shows (emphasis mine): “we couldn’t see / from where we stood in soft shadows / any signs that they were swallows // or bats”; “One seemed almost iridescent / as I tried to track / its crescent / flight across the hill.” Other poems consider moths, manatees, bees, swans and ladybirds; snowdrops and a cedar tree. Part II expands the view through conversations, theories and travel. What-ifs, consequences and regrets seep in. Parts III and IV incorporate mythical allusions, elegies and the concerns of motherhood. Sometimes the rhyme scheme adheres to a particular form. For instance, I loved “Triolet on My Mother’s 74th Birthday” – “You cannot imagine one season in another. … You cannot imagine life without your mother.” This is just my sort of poetry, sweet on the ear and rooted in nature and the everyday. A sample poem:

McAlpine is an associate professor of English at Oxford. Her second poetry collection is full of flora and fauna imagery. The title phrase comes from the opening poem, “Bats and Swallows” – in the “gloaming,” it’s hard to tell the difference between the flying creatures. The verse is bursting with alliteration and end rhymes, as just this first one shows (emphasis mine): “we couldn’t see / from where we stood in soft shadows / any signs that they were swallows // or bats”; “One seemed almost iridescent / as I tried to track / its crescent / flight across the hill.” Other poems consider moths, manatees, bees, swans and ladybirds; snowdrops and a cedar tree. Part II expands the view through conversations, theories and travel. What-ifs, consequences and regrets seep in. Parts III and IV incorporate mythical allusions, elegies and the concerns of motherhood. Sometimes the rhyme scheme adheres to a particular form. For instance, I loved “Triolet on My Mother’s 74th Birthday” – “You cannot imagine one season in another. … You cannot imagine life without your mother.” This is just my sort of poetry, sweet on the ear and rooted in nature and the everyday. A sample poem:

“Clementines”

New Year’s Day – another turning

of the sphere, with all we planned

in yesteryear as close to hand

as last night’s coals left unmanned

in the fire, still orange and burning.

It is the season for clementines

and citrus from Seville

and whatever brightness carries us until

leaves and petals once more fill

the treetops and the vines.

If ever you were to confess

some cold truth about love’s

dwindling, now would be the time – less

in order for things to improve

than for the half-bitter happiness

of peeling rinds

during mid-winter

recalling days that are behind

us and doors we cannot re-enter

and other doors we couldn’t find.

With thanks to Carcanet Press for the advanced e-copy for review.

Secrets of Adulthood: Simple Truths for Our Complex Lives by Gretchen Rubin

Rubin is one of the best self-help authors out there: Her books are practical, well-researched and genuinely helpful. She understands human nature and targets her strategies to suit different personality types. If you know her work, you’re likely aware of her fondness for aphorisms. “Sometimes, a single sentence can provide all the insight we need,” she believes. Here she collects her own pithy sayings relating to happiness, self-knowledge, relationships, work, creativity and decision-making. Some of the aphorisms were familiar to me through her previous books or her social media. They’re straightforward and sensible, distilling down to a few words truths we might be aware of but hadn’t truly absorbed. Like the great aphorists throughout history, Rubin relishes alliteration, repetition and contrasts. Some examples:

Rubin is one of the best self-help authors out there: Her books are practical, well-researched and genuinely helpful. She understands human nature and targets her strategies to suit different personality types. If you know her work, you’re likely aware of her fondness for aphorisms. “Sometimes, a single sentence can provide all the insight we need,” she believes. Here she collects her own pithy sayings relating to happiness, self-knowledge, relationships, work, creativity and decision-making. Some of the aphorisms were familiar to me through her previous books or her social media. They’re straightforward and sensible, distilling down to a few words truths we might be aware of but hadn’t truly absorbed. Like the great aphorists throughout history, Rubin relishes alliteration, repetition and contrasts. Some examples:

Accept yourself, and expect more from yourself.

I admire nature, and I am also nature. I resent traffic, and I am also traffic.

Work is the play of adulthood. If we’re not failing, we’re not trying hard enough.

Don’t wait until you have more free time. You may never have more free time.

This is not as meaty as her other work, and some parts feel redundant, but that’s the nature of the project. It would make a good bedside book for nibbles of inspiration. (Read via Edelweiss)

Which of these appeal to you?

Three on a Theme (and #ReadIndies): Nonfiction I Sponsored Last Year

Here in the UK we’re hunkering down against the high winds of Storm Eunice. We’ve already watched two trees come down in a neighbour’s garden (and they’re currently out there trying to shore up the fence!), and had news on the community Facebook page of a huge conifer down by the canal. Very sad. I hope you’re all safe and well and tucked up at home.

Today I’m looking back at several 2021 nonfiction releases I helped come into existence. The first and third I sponsored via Unbound, and the second through Dodo Ink. Supporting small publishers also ties this post into Karen and Lizzy’s February Read Indies initiative. All:

This Party’s Dead: Grief, Joy and Spilled Rum at the World’s Death Festivals by Erica Buist

A death tourism book? I’m there! This is actually the third I’ve read in recent years, after From Here to Eternity by Caitlin Doughty and Near the Exit by Lori Erickson. Buist’s journey was sparked off by the sudden death of her fiancé Dion’s father, Chris – he was dead for a week before his cleaner raised the alarm – and her burden of guilt. It’s an act of atonement for what happened to Chris and the fact that she and Dion, who used to lodge with him, weren’t there when he really needed it. It’s also her way of discovering a sense of the sacred around death, instead of simply fearing and hiding from it.

This takes place in roughly 2018. The author travelled to eight festivals in seven countries, starting with Mexico for the Day of the Dead and later for an exploration of Santa Muerte, a hero of the working class. Other destinations included Nepal, Sicily (“bones of the dead” biscotti), Madagascar (the “turning of the bones” ceremony – a days-long, extravagant party for a whole village), Thailand and Kyoto. The New Orleans chapter was a standout for me. It’s a city where the dead outnumber the living 10 to 1 (and did so even before Katrina), and graveyard and ghost tours are a common tourist activity.

This takes place in roughly 2018. The author travelled to eight festivals in seven countries, starting with Mexico for the Day of the Dead and later for an exploration of Santa Muerte, a hero of the working class. Other destinations included Nepal, Sicily (“bones of the dead” biscotti), Madagascar (the “turning of the bones” ceremony – a days-long, extravagant party for a whole village), Thailand and Kyoto. The New Orleans chapter was a standout for me. It’s a city where the dead outnumber the living 10 to 1 (and did so even before Katrina), and graveyard and ghost tours are a common tourist activity.

Buist is an entertaining writer, snappy and upbeat without ever seeming flippant as she discusses heavy topics. The mix of experience and research, the everyday and the momentous, is spot on and she recreates dialogue very well. I appreciated the earnest seeking here, and would happily read a book of hers on pretty much any subject. (New purchase from Unbound)

Trauma: Essays on Art and Mental Health, ed. Thom Cuell & Sam Mills

I’ll never learn: I left it nearly 10 months between finishing this and writing it up. And took no notes. So it’s nearly impossible to recreate the reading experience. What I do recall, however, is how wide-ranging and surprising I found this book. At first I had my doubts, thinking it was overkill to describe sad events like a break-up or loss as “traumatic”. But an essay midway through (which intriguingly trades off autobiographical text by Kirsty Logan and Freudian interpretation by Paul McQuade) set me straight: trauma cannot be quantified or compared; it’s all about the “unpreparedness of the subject. A traumatic event overwhelms all the defences laid out in advance against the encroachment of negative experience.”

The pieces can be straightforward memoir fragments or playful, experimental narratives more like autofiction. (Alex Pheby’s is in the second person, for instance.) Within those broad branches, though, the topics vary widely. James Miller writes about the collective horror at the Trump presidency. Emma Jane Unsworth recounts a traumatic delivery – I loved getting this taste of her autobiographical writing but, unfortunately, it outshone her full-length memoir, After the Storm, which I read later in the year. Susanna Crossman tells of dressing up as a clown for her clinical therapy work. Naomi Frisby (the much-admired blogger behind The Writes of Womxn) uses food metaphors to describe how she coped with the end of a bad relationship with a narcissist.

The pieces can be straightforward memoir fragments or playful, experimental narratives more like autofiction. (Alex Pheby’s is in the second person, for instance.) Within those broad branches, though, the topics vary widely. James Miller writes about the collective horror at the Trump presidency. Emma Jane Unsworth recounts a traumatic delivery – I loved getting this taste of her autobiographical writing but, unfortunately, it outshone her full-length memoir, After the Storm, which I read later in the year. Susanna Crossman tells of dressing up as a clown for her clinical therapy work. Naomi Frisby (the much-admired blogger behind The Writes of Womxn) uses food metaphors to describe how she coped with the end of a bad relationship with a narcissist.

As is inevitable with a collection this long, there are some essays that quickly fade in the memory and could have been omitted without weakening the book as a whole. But it’s not gracious to name names, and, anyway, it’s likely that different pieces will stand out for other readers based on their own experiences. (New purchase from Dodo Ink)

Four favourites:

- “Inheritance” by Christiana Spens (about investigating her grandparents’ lives through screen prints and writing after her father’s death and her son’s birth)

- “Blank Spaces” by Yvonna Conza (about the lure of suicide)

- “The Fish Bowl” by Monique Roffey (about everyday sexual harassment and an assault she underwent as a teenager; I enjoyed this so much more than her latest novel)

- “Thanks, I’ll Take the Chair” by Jude Cook, about being in therapy.

Women on Nature: 100+ Voices on Place, Landscape & the Natural World, ed. Katharine Norbury

It was over three years between when I pledged support and held the finished book in my hands; I can only imagine what a mammoth job compiling it was for Katharine Norbury (author of The Fish Ladder). The subtitle on the title page explains the limits she set: “An anthology of women’s writing about the natural world in the east Atlantic archipelago.” So, broadly, British and Irish writers, but within that there’s a lot of scope for variety: fragments of fiction (e.g., a passage from Jane Eyre), plenty of poetry, but mostly nonfiction narratives – some work in autobiographical reflection; others are straightforward nature or travel writing. Excerpts from previously published works trade off with essays produced specifically for this volume. So I encountered snippets of works I’d read by the likes of Miriam Darlington, Melissa Harrison, Sara Maitland, Polly Samson and Nan Shepherd. The timeline stretches from medieval mystics to today’s Guardian Country Diarists and BIPOC nature writers.

For most of the last seven months of 2021, I kept this as a bedside book, reading one or two pieces on most nights. It wasn’t until early this year that I brought it downstairs and started working it into my regular daily stacks so that I would see more progress. At first I quibbled (internally) with the decision to structure the book alphabetically by author. I wondered if more might have been done to group the pieces by region or theme. But besides being an unwieldy task, that might have made the contents seem overly determined. Instead, you get the serendipity of different works conversing with each other. So, for example, Katrina Porteous’s dialect poem about a Northumberland fisherman is followed immediately by Jini Reddy’s account of a trip to Lindisfarne; Margaret Cavendish’s 1653 dialogue in verse between an oak tree and the man cutting him down leads perfectly into an excerpt from Nicola Chester’s On Gallows Down describing a confrontation with tree fellers.

For most of the last seven months of 2021, I kept this as a bedside book, reading one or two pieces on most nights. It wasn’t until early this year that I brought it downstairs and started working it into my regular daily stacks so that I would see more progress. At first I quibbled (internally) with the decision to structure the book alphabetically by author. I wondered if more might have been done to group the pieces by region or theme. But besides being an unwieldy task, that might have made the contents seem overly determined. Instead, you get the serendipity of different works conversing with each other. So, for example, Katrina Porteous’s dialect poem about a Northumberland fisherman is followed immediately by Jini Reddy’s account of a trip to Lindisfarne; Margaret Cavendish’s 1653 dialogue in verse between an oak tree and the man cutting him down leads perfectly into an excerpt from Nicola Chester’s On Gallows Down describing a confrontation with tree fellers.

I’d highly recommend this for those who are fairly new to the UK nature writing scene and/or would like to read more by women. Keep it as a coffee table book or a bedside read and pick it up between other things. You’ll soon find your own favourites. (New purchase from Unbound)

Five favourites:

- “Caravan” by Sally Goldsmith (a Sheffield tree defender)

- “Enlli: The Living Island” by Pippa Marland (about the small Welsh island of Bardsey)

- “An Affinity with Bees” by Elizabeth Rose Murray (about beekeeping, and her difficult mother, who called herself “the queen bee”)

- “An Island Ecology” by Sarah Thomas (about witnessing a whale hunt on the Faroe Islands)

- My overall favourite: “Arboreal” by Jean McNeil (about living in Antarctica for a winter and the contrast between that treeless continent and Canada, where she grew up, and England, where she lives now)

“It occurred to me that trees were part of the grammar of one’s life, as much as any spoken language. … To see trees every day and to be seen by them is a privilege.”

Stay strong, trees!

Sponsored any books, or read any from indie publishers, recently?

Reading from the Wainwright Prize Longlists

The Wainwright Prize is one that I’ve ended up following closely almost by accident, simply because I tend to read most of the nature books released in the UK in any given year. A few months back I cheekily wrote to the prize director, proffering myself as a judge and appending a list of eligible titles I hoped were in consideration. Although they already had a full judging roster for 2021, I got a very kind reply thanking me for my recommendations and promising to bear me in mind for the future. Fifteen of my 25 suggestions made it onto the lists below.

This is the second year that there have been two awards, one for writing on UK nature and the other on global conservation themes. Tomorrow (August 4th) at 4 p.m., the longlists will be narrowed down to shortlists. I happened to have read and reviewed 12 of the nominees already, and I have a few others in progress.

UK nature writing longlist:

The Circling Sky by Neil Ansell: Hoping to reclaim an ancestral connection, Ansell visited the New Forest some 30 times between January 2019 and January 2020, observing the unfolding seasons and the many uncommon and endemic species its miles house. He weaves together his personal story, the shocking history of forced Gypsy relocation into forest compounds starting in the 1920s, and the unfairness of land ownership in Britain. The New Forest is a model of both wildlife-friendly land management and freedom of human access. (On my Best of 2021 so far list.)

The Circling Sky by Neil Ansell: Hoping to reclaim an ancestral connection, Ansell visited the New Forest some 30 times between January 2019 and January 2020, observing the unfolding seasons and the many uncommon and endemic species its miles house. He weaves together his personal story, the shocking history of forced Gypsy relocation into forest compounds starting in the 1920s, and the unfairness of land ownership in Britain. The New Forest is a model of both wildlife-friendly land management and freedom of human access. (On my Best of 2021 so far list.)

T he Screaming Sky by Charles Foster: A Renaissance man as well versed in law and theology as he is in natural history, Foster is obsessed with swifts and ashamed of his own species: for looking down at their feet when they could be watching the skies; for the “pathological tidiness” that leaves birds and other creatures no place to live. He delivers heaps of information on the birds but refuses to stick to a just-the-facts approach. The book quotes frequently from poetry and the prose is full of sharp turns of phrase and whimsy. (Also on my Best of 2021 so far list.)

he Screaming Sky by Charles Foster: A Renaissance man as well versed in law and theology as he is in natural history, Foster is obsessed with swifts and ashamed of his own species: for looking down at their feet when they could be watching the skies; for the “pathological tidiness” that leaves birds and other creatures no place to live. He delivers heaps of information on the birds but refuses to stick to a just-the-facts approach. The book quotes frequently from poetry and the prose is full of sharp turns of phrase and whimsy. (Also on my Best of 2021 so far list.)

Featherhood by Charlie Gilmour: As an aimless twentysomething, Gilmour tried to rekindle a relationship with his unreliable poet father at the same time that he and his wife were pondering starting a family of their own. Meanwhile, he was raising Benzene, a magpie that fell out of the nest and ended up in his care. The experience taught him responsibility and compassionate care for another creature. Gilmour makes elegant use of connections and metaphors. He’s so good at scenes, dialogue and emotion – a natural writer.

Featherhood by Charlie Gilmour: As an aimless twentysomething, Gilmour tried to rekindle a relationship with his unreliable poet father at the same time that he and his wife were pondering starting a family of their own. Meanwhile, he was raising Benzene, a magpie that fell out of the nest and ended up in his care. The experience taught him responsibility and compassionate care for another creature. Gilmour makes elegant use of connections and metaphors. He’s so good at scenes, dialogue and emotion – a natural writer.

Seed to Dust by Marc Hamer: Hamer paints a loving picture of his final year at the 12-acre British garden he tended for decades. In few-page essays, the book journeys through a gardener’s year. This is creative nonfiction rather than straightforward memoir. The prose is adorned with lovely metaphors. In places, the language edges towards purple and the content becomes repetitive – a danger of the diary format. However, the focus on emotions and self-perception – rare for a male nature writer – is refreshing. (Reviewed for Foreword.)

Seed to Dust by Marc Hamer: Hamer paints a loving picture of his final year at the 12-acre British garden he tended for decades. In few-page essays, the book journeys through a gardener’s year. This is creative nonfiction rather than straightforward memoir. The prose is adorned with lovely metaphors. In places, the language edges towards purple and the content becomes repetitive – a danger of the diary format. However, the focus on emotions and self-perception – rare for a male nature writer – is refreshing. (Reviewed for Foreword.)

The Stubborn Light of Things by Melissa Harrison: A collection of five and a half years’ worth of Harrison’s monthly Nature Notebook columns for The Times. Initially based in South London, Harrison moved to the Suffolk countryside in late 2017. In the grand tradition of Gilbert White, she records when she sees her firsts of a year. I appreciate how hands-on and practical Harrison is. She never misses an opportunity to tell readers about ways they can create habitat for wildlife and get involved in citizen science projects. (Reviewed for Shiny New Books.)

The Stubborn Light of Things by Melissa Harrison: A collection of five and a half years’ worth of Harrison’s monthly Nature Notebook columns for The Times. Initially based in South London, Harrison moved to the Suffolk countryside in late 2017. In the grand tradition of Gilbert White, she records when she sees her firsts of a year. I appreciate how hands-on and practical Harrison is. She never misses an opportunity to tell readers about ways they can create habitat for wildlife and get involved in citizen science projects. (Reviewed for Shiny New Books.)

Birdsong in a Time of Silence by Steven Lovatt: During the UK’s first lockdown, with planes grounded and cars stationary, many remarked on the quiet. All the better to hear birds going about their usual spring activities. For Lovatt, it was the excuse he needed to return to his childhood birdwatching hobby. In between accounts of his spring walks, he tells lively stories of common birds’ anatomy, diet, lifecycle, migration routes, and vocalizations. Lovatt’s writing is introspective and poetic, delighting in metaphors for sounds.

Birdsong in a Time of Silence by Steven Lovatt: During the UK’s first lockdown, with planes grounded and cars stationary, many remarked on the quiet. All the better to hear birds going about their usual spring activities. For Lovatt, it was the excuse he needed to return to his childhood birdwatching hobby. In between accounts of his spring walks, he tells lively stories of common birds’ anatomy, diet, lifecycle, migration routes, and vocalizations. Lovatt’s writing is introspective and poetic, delighting in metaphors for sounds.

Vesper Flights by Helen Macdonald: Though written for various periodicals and ranging in topic from mushroom-hunting to deer–vehicle collisions and in scope from deeply researched travel pieces to one-page reminiscences, these essays form a coherent whole. Equally reliant on argument and epiphany, the book has more to say about human–animal interactions in one of its essays than some whole volumes manage. Her final lines are always breath-taking. I’d rather read her writing on any subject than almost any other author’s. (My top nonfiction release of 2020.)

Vesper Flights by Helen Macdonald: Though written for various periodicals and ranging in topic from mushroom-hunting to deer–vehicle collisions and in scope from deeply researched travel pieces to one-page reminiscences, these essays form a coherent whole. Equally reliant on argument and epiphany, the book has more to say about human–animal interactions in one of its essays than some whole volumes manage. Her final lines are always breath-taking. I’d rather read her writing on any subject than almost any other author’s. (My top nonfiction release of 2020.)

Skylarks with Rosie by Stephen Moss: Devoting a chapter each to the first 13 weeks of the initial UK lockdown, Moss traces the season’s development in Somerset alongside his family’s experiences and what was emerging on the national news. He welcomed migrating birds and marked his first sightings of butterflies and other insects. Nature came to him, too. For once, he felt that he had truly appreciated the spring, noting its every milestone and “rediscovering the joys of wildlife-watching close to home.”

Skylarks with Rosie by Stephen Moss: Devoting a chapter each to the first 13 weeks of the initial UK lockdown, Moss traces the season’s development in Somerset alongside his family’s experiences and what was emerging on the national news. He welcomed migrating birds and marked his first sightings of butterflies and other insects. Nature came to him, too. For once, he felt that he had truly appreciated the spring, noting its every milestone and “rediscovering the joys of wildlife-watching close to home.”

Thin Places by Kerri ní Dochartaigh: I received a proof copy from Canongate and twice tried the first few pages, but couldn’t wade through the excessive lyricism (and downright incorrect information – weaving a mystical description of a Winter Moth’s flight, she keeps referring to the creature as “she,” whereas when I showed the passage to my entomologist husband he told me that the females of that species are flightless). I’m told it develops into an eloquent memoir of growing up during the Troubles. Perhaps reminiscent of The Outrun?

Thin Places by Kerri ní Dochartaigh: I received a proof copy from Canongate and twice tried the first few pages, but couldn’t wade through the excessive lyricism (and downright incorrect information – weaving a mystical description of a Winter Moth’s flight, she keeps referring to the creature as “she,” whereas when I showed the passage to my entomologist husband he told me that the females of that species are flightless). I’m told it develops into an eloquent memoir of growing up during the Troubles. Perhaps reminiscent of The Outrun?

Into the Tangled Bank by Lev Parikian: A delightfully Bryson-esque tour that moves ever outwards, starting with the author’s own home and garden and proceeding to take in his South London patch and his journeys around the British Isles before closing with the wonders of the night sky. By slowing down to appreciate what is all around us, he proposes, we might enthuse others to engage with nature. With the zeal of a recent convert, he guides readers through momentous sightings and everyday moments of connection. (When I reviewed this in July 2020, I correctly predicted it would make the longlist!)

Into the Tangled Bank by Lev Parikian: A delightfully Bryson-esque tour that moves ever outwards, starting with the author’s own home and garden and proceeding to take in his South London patch and his journeys around the British Isles before closing with the wonders of the night sky. By slowing down to appreciate what is all around us, he proposes, we might enthuse others to engage with nature. With the zeal of a recent convert, he guides readers through momentous sightings and everyday moments of connection. (When I reviewed this in July 2020, I correctly predicted it would make the longlist!)

English Pastoral by James Rebanks: This struck me for its bravery, good sense and humility. The topics of the degradation of land and the dangers of intensive farming are of the utmost importance. Daring to undermine his earlier work and his online persona, the author questions the mythos of modern farming, contrasting its practices with the more sustainable and wildlife-friendly ones his grandfather espoused. Old-fashioned can still be best if it means preserving soil health, river quality and the curlew population.

English Pastoral by James Rebanks: This struck me for its bravery, good sense and humility. The topics of the degradation of land and the dangers of intensive farming are of the utmost importance. Daring to undermine his earlier work and his online persona, the author questions the mythos of modern farming, contrasting its practices with the more sustainable and wildlife-friendly ones his grandfather espoused. Old-fashioned can still be best if it means preserving soil health, river quality and the curlew population.

I Belong Here by Anita Sethi: I recently skimmed this from the library. Two things are certain: 1) BIPOC writers should appear more frequently on prize lists, so it’s wonderful that Sethi is here; 2) this book was poorly put together. It’s part memoir of an incident of racial abuse, part political manifesto, and part quite nice travelogue. The parts don’t make a whole. The contents are repetitive and generic (definitions, overstretched metaphors). Sethi had a couple of strong articles here, not a whole book. I blame her editors for not eliciting better.

I Belong Here by Anita Sethi: I recently skimmed this from the library. Two things are certain: 1) BIPOC writers should appear more frequently on prize lists, so it’s wonderful that Sethi is here; 2) this book was poorly put together. It’s part memoir of an incident of racial abuse, part political manifesto, and part quite nice travelogue. The parts don’t make a whole. The contents are repetitive and generic (definitions, overstretched metaphors). Sethi had a couple of strong articles here, not a whole book. I blame her editors for not eliciting better.

The Wild Silence by Raynor Winn: I only skimmed this, too. I got the feeling her publisher was desperate to capitalize on the popularity of her first book and said “give us whatever you have,” cramming drafts of several different projects (a memoir that went deeper into the past, a ‘what happened next’ sequel to The Salt Path, and an Iceland travelogue) into one book and rushing it through to publication. Winn’s writing is still strong, though; she captures dialogue and scenes naturally, and you believe in how much the connection to the land matters to her.

The Wild Silence by Raynor Winn: I only skimmed this, too. I got the feeling her publisher was desperate to capitalize on the popularity of her first book and said “give us whatever you have,” cramming drafts of several different projects (a memoir that went deeper into the past, a ‘what happened next’ sequel to The Salt Path, and an Iceland travelogue) into one book and rushing it through to publication. Winn’s writing is still strong, though; she captures dialogue and scenes naturally, and you believe in how much the connection to the land matters to her.

Global conservation longlist:

Like last year, I’ve read much less from this longlist since I gravitate more towards nature writing and memoirs than to hard or popular science. So I have read, am reading or plan to read about half of this list, as opposed to pretty much all of the other one.

Islands of Abandonment by Cal Flyn: This was on my Most Anticipated list for 2021 and I treated myself to a copy while we were up in Northumberland. I’m nearly a third of the way through this fascinating, well-written tour of places where nature has spontaneously regenerated due to human neglect: depleted mining areas in Scotland, former conflict zones, Soviet collective farms turned feral, sites of nuclear disaster, and so on. I’m about to start the chapter on Chernobyl, which I expect to echo Mark O’Connell’s Notes from an Apocalypse.

Islands of Abandonment by Cal Flyn: This was on my Most Anticipated list for 2021 and I treated myself to a copy while we were up in Northumberland. I’m nearly a third of the way through this fascinating, well-written tour of places where nature has spontaneously regenerated due to human neglect: depleted mining areas in Scotland, former conflict zones, Soviet collective farms turned feral, sites of nuclear disaster, and so on. I’m about to start the chapter on Chernobyl, which I expect to echo Mark O’Connell’s Notes from an Apocalypse.

What If We Stopped Pretending? by Jonathan Franzen: The message of this controversial 2019 New Yorker essay is simple: climate breakdown is here, so stop denying it and talking of “saving the planet”; it’s too late. Global warming is locked in; the will is not there to curb growth, overhaul economies, and ask people to relinquish developed world lifestyles. Instead, start preparing for the fallout (refugees) and saving what can be saved (particular habitats and species). Franzen is realistic about human nature and practical about what to do next.

What If We Stopped Pretending? by Jonathan Franzen: The message of this controversial 2019 New Yorker essay is simple: climate breakdown is here, so stop denying it and talking of “saving the planet”; it’s too late. Global warming is locked in; the will is not there to curb growth, overhaul economies, and ask people to relinquish developed world lifestyles. Instead, start preparing for the fallout (refugees) and saving what can be saved (particular habitats and species). Franzen is realistic about human nature and practical about what to do next.

Entangled Life by Merlin Sheldrake: Sheldrake’s enthusiasm is infectious as he researches fungal life in the tropical forests of Panama, accompanies truffle hunters in Italy, and takes part in a clinical study on the effects of LSD (derived from a fungus). More than a travel memoir, though, this is a work of proper science – over 100 pages are taken up by notes, bibliography and index. This is a perspective-altering text that reveals our unconscious species bias. I’ve recommended it widely, even to those who tend not to read nonfiction.

Entangled Life by Merlin Sheldrake: Sheldrake’s enthusiasm is infectious as he researches fungal life in the tropical forests of Panama, accompanies truffle hunters in Italy, and takes part in a clinical study on the effects of LSD (derived from a fungus). More than a travel memoir, though, this is a work of proper science – over 100 pages are taken up by notes, bibliography and index. This is a perspective-altering text that reveals our unconscious species bias. I’ve recommended it widely, even to those who tend not to read nonfiction.

Ice Rivers by Jemma Wadham: I have this out from the library and am two-thirds through. Wadham, a leading glaciologist, introduces readers to the science of glaciers: where they are, what lives on and under them, how they move and change, and the grave threats they face (and, therefore, so do we). The science, even dumbed down, is a little hard to follow, but I love experiencing extreme landscapes like Greenland and Antarctica with her. She neatly inserts tiny mentions of her personal life, such as her mother’s death, a miscarriage and a benign brain cyst.

Ice Rivers by Jemma Wadham: I have this out from the library and am two-thirds through. Wadham, a leading glaciologist, introduces readers to the science of glaciers: where they are, what lives on and under them, how they move and change, and the grave threats they face (and, therefore, so do we). The science, even dumbed down, is a little hard to follow, but I love experiencing extreme landscapes like Greenland and Antarctica with her. She neatly inserts tiny mentions of her personal life, such as her mother’s death, a miscarriage and a benign brain cyst.

The rest of the longlist is:

- A Life on Our Planet by David Attenborough – I’ve never read a book by Attenborough (and tend to worry this sort of book would be ghostwritten), but wouldn’t be averse to doing so.

Fathoms by Rebecca Giggs – All about whales. Kate raved about it. I have this on hold at the library.

Fathoms by Rebecca Giggs – All about whales. Kate raved about it. I have this on hold at the library.- Net Zero: How We Stop Causing Climate Change by Dieter Helm

- Under a White Sky by Elizabeth Kolbert – I have read her before and would again.

- Riders on the Storm by Alistair McIntosh – My husband has read several of his books and rates them highly.

- The New Climate War by Michael E. Mann

- The Reindeer Chronicles by Judith D. Schwartz – I’ve been keen to read this one.

- A World on the Wing by Scott Weidensaul – My husband is reading this from the library.

My predictions/wishes for the shortlists:

It’s high time that a woman won again. And why not for both, eh? (Amy Liptrot is still the only female winner in the Prize’s seven-year history, for The Outrun in 2016.)

UK nature writing:

- The Circling Sky by Neil Ansell

- The Screaming Sky by Charles Foster

- Featherhood by Charlie Gilmour

- Vesper Flights by Helen Macdonald*

- English Pastoral by James Rebanks

- I Belong Here by Anita Sethi

- The Wild Silence by Raynor Winn

Writing on global conservation:

- Islands of Abandonment by Cal Flyn*

- Fathoms by Rebecca Giggs

- Under a White Sky by Elizabeth Kolbert

- Entangled Life by Merlin Sheldrake

- Ice Rivers by Jemma Wadham

- A World on the Wing by Scott Weidensaul

*Overall winners, if I had my way.

Have you read anything from the Wainwright Prize longlists?

Do any of these books interest you?

Recent Reviews for Shiny New Books: Poetry, Fiction and Nature Writing

First up was a rundown of my five favorite poetry releases of the year, starting with…

Dearly by Margaret Atwood

Dearly is a treasure trove, twice the length of the average poetry collection and rich with themes of memory, women’s rights, environmental crisis, and bereavement. It is reflective and playful, melancholy and hopeful. I can highly recommend it, even to non-poetry readers, because it is led by its themes; although there are layers to explore, these poems are generally about what they say they’re about, and more material than abstract. Alliteration, repetition, internal and slant rhymes, and neologisms will delight language lovers and make the book one to experience aloud as well as on paper. Atwood’s imagery ranges from the Dutch masters to The Wizard of Oz. Her frame of reference is as wide as the array of fields she’s written in over the course of over half a century.

Dearly is a treasure trove, twice the length of the average poetry collection and rich with themes of memory, women’s rights, environmental crisis, and bereavement. It is reflective and playful, melancholy and hopeful. I can highly recommend it, even to non-poetry readers, because it is led by its themes; although there are layers to explore, these poems are generally about what they say they’re about, and more material than abstract. Alliteration, repetition, internal and slant rhymes, and neologisms will delight language lovers and make the book one to experience aloud as well as on paper. Atwood’s imagery ranges from the Dutch masters to The Wizard of Oz. Her frame of reference is as wide as the array of fields she’s written in over the course of over half a century.

I’ll let you read the whole article to discover my four runners-up. (They’ll also be appearing in my fiction & poetry best-of post next week.)

Next was one of my most anticipated reads of the second half of 2020. (I was drawn to it by Susan’s review.)

Artifact by Arlene Heyman

Lottie’s story is a case study of the feminist project to reconcile motherhood and career (in this case, scientific research). In the generic more than the scientific meaning of the word, the novel is indeed about artifacts – as in works by Doris Lessing, Penelope Lively and Carol Shields, the goal is to unearth the traces of a woman’s life. The long chapters are almost like discrete short stories. Heyman follows Lottie through years of schooling and menial jobs, through a broken marriage and a period of single parenthood, and into a new relationship. There were aspects of the writing that didn’t work for me and I found the book as a whole more intellectually noteworthy than engaging as a story. A piercing – if not notably subtle – story of women’s choices and limitations in the latter half of the twentieth century. I’d recommend it to fans of Forty Rooms and The Female Persuasion.

Lottie’s story is a case study of the feminist project to reconcile motherhood and career (in this case, scientific research). In the generic more than the scientific meaning of the word, the novel is indeed about artifacts – as in works by Doris Lessing, Penelope Lively and Carol Shields, the goal is to unearth the traces of a woman’s life. The long chapters are almost like discrete short stories. Heyman follows Lottie through years of schooling and menial jobs, through a broken marriage and a period of single parenthood, and into a new relationship. There were aspects of the writing that didn’t work for me and I found the book as a whole more intellectually noteworthy than engaging as a story. A piercing – if not notably subtle – story of women’s choices and limitations in the latter half of the twentieth century. I’d recommend it to fans of Forty Rooms and The Female Persuasion.

Finally, I contributed a dual review of two works of nature writing that would make perfect last-minute Christmas gifts for outdoorsy types and/or would be perfect bedside books for reading along with the English seasons into a new year.

The Stubborn Light of Things by Melissa Harrison

This collects five and a half years’ worth of Harrison’s monthly Nature Notebook columns for The Times. The book falls into two rough halves, “City” and “Country”: initially based in South London, Harrison moved to the Suffolk countryside in late 2017. In the grand tradition of Gilbert White, she records when she sees her firsts of a year. Often, she need look no further than her own home and garden. I appreciated how hands-on and practical she is: She’s always picking up dead animals to clean up and display the skeletons, and she never misses an opportunity to tell readers about ways they can create habitat for wildlife (e.g. bat and bird nest boxes that can be incorporated into buildings) and get involved in citizen science projects like moth recording.

This collects five and a half years’ worth of Harrison’s monthly Nature Notebook columns for The Times. The book falls into two rough halves, “City” and “Country”: initially based in South London, Harrison moved to the Suffolk countryside in late 2017. In the grand tradition of Gilbert White, she records when she sees her firsts of a year. Often, she need look no further than her own home and garden. I appreciated how hands-on and practical she is: She’s always picking up dead animals to clean up and display the skeletons, and she never misses an opportunity to tell readers about ways they can create habitat for wildlife (e.g. bat and bird nest boxes that can be incorporated into buildings) and get involved in citizen science projects like moth recording.

The book’s final two entries were set during the UK’s first COVID-19 lockdown in spring 2020 – a notably fine season. This inspired me to review it alongside…

The Consolation of Nature by Michael McCarthy, Jeremy Mynott and Peter Marren

A tripartite diary of the coronavirus spring kept by three veteran nature writers based in southern England (all of them familiar to me through their involvement with New Networks for Nature and its annual Nature Matters conferences). The entries, of a similar length to Harrison’s, are grouped into chronological chapters from 21 March to 31 May. While the authors focus in these 10 weeks on their wildlife sightings – red kites, kestrels, bluebells, fungal fairy rings and much more – they also log government advice and death tolls. They achieve an ideal balance between current events and the timelessness of nature, enjoyed all the more in 2020’s unprecedented spring because of a dearth of traffic noise.

A tripartite diary of the coronavirus spring kept by three veteran nature writers based in southern England (all of them familiar to me through their involvement with New Networks for Nature and its annual Nature Matters conferences). The entries, of a similar length to Harrison’s, are grouped into chronological chapters from 21 March to 31 May. While the authors focus in these 10 weeks on their wildlife sightings – red kites, kestrels, bluebells, fungal fairy rings and much more – they also log government advice and death tolls. They achieve an ideal balance between current events and the timelessness of nature, enjoyed all the more in 2020’s unprecedented spring because of a dearth of traffic noise.

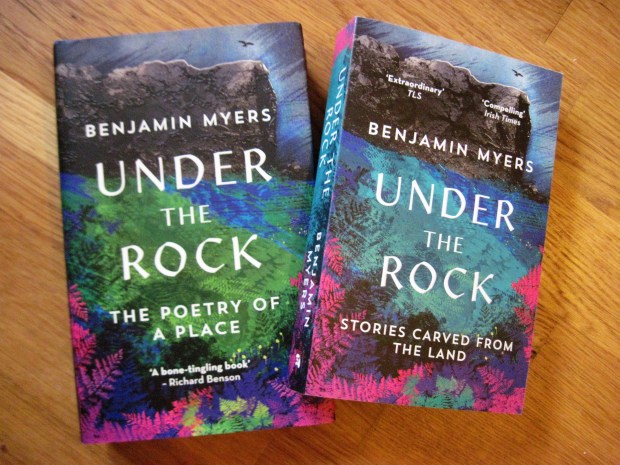

Under the Rock by Benjamin Myers: Paperback Giveaway

Benjamin Myers’s Under the Rock was my nonfiction book of 2018, so I’m delighted to be kicking off the blog tour for its paperback release on the 25th (with a new subtitle, “Stories Carved from the Land”). I’m reprinting my Shiny New Books review below, with permission, and on behalf of Elliott & Thompson I am also hosting a giveaway of a copy of the paperback. Leave a comment saying that you’d like to win and I will choose one entry at random at the end of the day on Tuesday the 30th. (Sorry, UK only.)

My review:

Benjamin Myers has been having a bit of a moment. In 2017 Bluemoose Books published his fifth novel, The Gallows Pole, which went on to win the Roger Deakin Award and the Walter Scott Prize for Historical Fiction and is now on its fourth printing. This taste of fame has brought renewed attention to his earlier work, including Beastings (2014), recipient of the Northern Writers’ Award. I’ve been interested in Myers’s work ever since I read an extract from the then-unpublished The Gallows Pole in Autumn, the Wildlife Trusts anthology edited by Melissa Harrison, but this is the first of his books that I’ve managed to read.

“Unremarkable places are made remarkable by the minds that map them,” Myers writes, and that is certainly true of Scout Rock, a landmark overlooking Mytholmroyd, near where the author lives in the Calder Valley of West Yorkshire. When he moved up there from London over a decade ago, he and his wife lived in a rental cottage built in 1640. He approached his new patch with admirable curiosity, and supplemented the observations he made from his study window with frequent long walks with his dog, Heathcliff (“Walking is writing with your feet”), and research into the history of the area. The result is a divagating, lyrical book that ranges from geology to true crime but has an underlying autobiographical vein.

Ted Hughes was born nearby, the Brontës not that much further away, and Hebden Bridge, in particular, has become a bastion of avant-garde artists and musicians. Myers also gets plenty of mileage out of his eccentric neighbours and postman. It’s a town that seems to attract oddballs and renegades, from the vigilantes who poisoned the fishing hole to an overdose victim who turns up beneath a stand of Himalayan balsam. A strange preponderance of criminals has come from the region, too, including sexual offenders like Jimmy Savile and serial killers such as the Yorkshire Ripper and Harold Shipman (‘Doctor Death’).

On his walks Myers discovers the old town tip, still full of junk that won’t biodegrade for hundreds more years, and finds traces of the asbestos that was dumped by Acre Mill, creating a national scandal. This isn’t old-style nature writing in search of a few remaining unspoiled places. Instead, it’s part of a growing literary interest in the ‘edgelands’ between settlement and the wild – places where the human impact is undeniable but nature is creeping back in. (Other recent examples would be Common Ground by Rob Cowen, Landfill by Tim Dee, Edgelands by Paul Farley and Michael Symmons Roberts, and Outskirts by John Grindrod.)

Under the Rock gives a keen sense of the seasons’ change and the seemingly inevitable melancholy that accompanies bad weather. A winter of non-stop rain left Myers nigh on delirious with flu; Storm Eva caused the Calder River to flood. He was a part of the effort to rescue trapped pensioners. Heartening as it is to see how the disaster brought people together – Sikh and Muslim charities and Syrian refugees were among the first to help – looting also resulted. One of the most remarkable things about this book is how Myers takes in such extremes of behaviour, along with mundanities, and makes them all part of a tapestry of life.

The book’s recurring themes tangle through all of the sections, even though it has been given a somewhat arbitrary four-part structure (Wood – Earth – Water – Rock). Interludes between these major parts transcribe Myers’s field notes, which are more like impromptu poems that he wrote in a notebook kept in his coat pocket. The artistry of these snippets of poetry is incredible given that they were written in situ, and their alliteration bleeds into his prose as well. My favourite of the poems was “On Lighting the First Fire”:

Autumn burns

the sky

the woods

the valley

death is everywhere

but beneath

the golden cloak

the seeds of

a summer’s

dreaming still sing.

The Field Notes sections are illustrated with Myers’s own photographs, which, again, are of enviable quality. I came away from this feeling like Myers could write anything – a thank-you note, a shopping list – and make it read as profound literature. Every sentence is well-crafted and memorable. There is also a wonderful sense of rhythm to his pages, with a pithy sentence appearing every couple of paragraphs to jolt you to attention.

“Writing is a form of alchemy,” Myers declares. “It’s a spell, and the writer is the magician.” I certainly fell under the author’s spell here. While his eyes are open to the many distressing political and environmental changes of the last few years, the ancient perspective of the Rock reminds him that, though humans are ultimately insignificant and individual lives are short, we can still rejoice in our experiences of the world’s beauty while we’re here.

From the publisher:

“Benjamin Myers was born in Durham in 1976. He is a prize-winning author, journalist and poet. His recent novels are each set in a different county of northern England, and are heavily inspired by rural landscapes, mythology, marginalised characters, morality, class, nature, dialect and post-industrialisation. They include The Gallows Pole, winner of the Walter Scott Prize for Historical Fiction, and recipient of the Roger Deakin Award; Turning Blue, 2016; Beastings, 2014 (Portico Prize for Literature & Northern Writers’ Award winner), Pig Iron, 2012 (Gordon Burn Prize winner & Guardian Not the Booker Prize runner-up); and Richard, a Sunday Times Book of the Year 2010. Bloomsbury will publish his new novel, The Offing, in August 2019.

As a journalist, he has written widely about music, arts and nature. He lives in the Upper Calder Valley, West Yorkshire, the inspiration for Under the Rock.”

Burnet, Cumulus and Moss are “Hidden Folk” (like Iceland’s elves), ancient, tiny beings who hibernate for winter in an ash tree. When they lose their home and Cumulus, the oldest, starts fading away, they set off on a journey to look for more of their kind and figure out what is happening. This eventually takes them to “the Hive” (London, presumably); they are helped along the way by creatures they might have been wary of: they hitch rides on deer and pigeons, and a starling, fox and rat are their allies in the city.

Burnet, Cumulus and Moss are “Hidden Folk” (like Iceland’s elves), ancient, tiny beings who hibernate for winter in an ash tree. When they lose their home and Cumulus, the oldest, starts fading away, they set off on a journey to look for more of their kind and figure out what is happening. This eventually takes them to “the Hive” (London, presumably); they are helped along the way by creatures they might have been wary of: they hitch rides on deer and pigeons, and a starling, fox and rat are their allies in the city. A single-species monograph, this was more academic than I expected from Little Toller – it has statistics, tables and figures. So, it contains everything you ever wanted to know about ash trees, and then some. I actually bought it for my husband, who has found the late Rackham’s research on British landscapes useful, but thought I’d take a look as well. (The rental house we recently left had a self-seeded ash in the front garden that sprang up to almost the height of the house within the five years we lived there. Every time our landlords came round, we held our breath waiting for them to notice that the roots had started to push up the pavement and tell us it had to be cut down, but until now it has survived.)

A single-species monograph, this was more academic than I expected from Little Toller – it has statistics, tables and figures. So, it contains everything you ever wanted to know about ash trees, and then some. I actually bought it for my husband, who has found the late Rackham’s research on British landscapes useful, but thought I’d take a look as well. (The rental house we recently left had a self-seeded ash in the front garden that sprang up to almost the height of the house within the five years we lived there. Every time our landlords came round, we held our breath waiting for them to notice that the roots had started to push up the pavement and tell us it had to be cut down, but until now it has survived.)

A brother steals the main character’s object of affection in The Crow Road by Iain Banks and Sacred Country by Rose Tremain.

A brother steals the main character’s object of affection in The Crow Road by Iain Banks and Sacred Country by Rose Tremain.

Piranesi by Susanna Clarke [Sept. 15, Bloomsbury] “Piranesi’s house is no ordinary building: its rooms are infinite, its corridors endless. … For readers of Neil Gaiman’s The Ocean at the End of the Lane … Piranesi introduces an astonishing new world.” It feels like forever since we had a book from Clarke. I remember devouring Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell during a boating holiday on the Norfolk Broads in 2006. But whew: this one is only 272 pages.

Piranesi by Susanna Clarke [Sept. 15, Bloomsbury] “Piranesi’s house is no ordinary building: its rooms are infinite, its corridors endless. … For readers of Neil Gaiman’s The Ocean at the End of the Lane … Piranesi introduces an astonishing new world.” It feels like forever since we had a book from Clarke. I remember devouring Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell during a boating holiday on the Norfolk Broads in 2006. But whew: this one is only 272 pages. The Swallowed Man by Edward Carey [Nov. 5, Gallic / Oct. 27, Riverhead] “A beautiful and haunting imagining of the years Geppetto spends within the belly of a sea beast. Drawing upon the Pinocchio story while creating something entirely his own, Carey tells an unforgettable tale of fatherly love and loss, pride and regret, and of the sustaining power of art and imagination.” His

The Swallowed Man by Edward Carey [Nov. 5, Gallic / Oct. 27, Riverhead] “A beautiful and haunting imagining of the years Geppetto spends within the belly of a sea beast. Drawing upon the Pinocchio story while creating something entirely his own, Carey tells an unforgettable tale of fatherly love and loss, pride and regret, and of the sustaining power of art and imagination.” His

Dearly: New Poems by Margaret Atwood [Nov. 10, Chatto & Windus / Ecco / McClelland & Stewart] “By turns moving, playful and wise, the poems … are about absences and endings, ageing and retrospection, but also about gifts and renewals. They explore bodies and minds in transition … Werewolves, sirens and dreams make their appearance, as do various forms of animal life and fragments of our damaged environment.”

Dearly: New Poems by Margaret Atwood [Nov. 10, Chatto & Windus / Ecco / McClelland & Stewart] “By turns moving, playful and wise, the poems … are about absences and endings, ageing and retrospection, but also about gifts and renewals. They explore bodies and minds in transition … Werewolves, sirens and dreams make their appearance, as do various forms of animal life and fragments of our damaged environment.” Bright Precious Thing: A Memoir by Gail Caldwell [July 7, Random House] “In a voice as candid as it is evocative, Gail Caldwell traces a path from her west Texas girlhood through her emergence as a young daredevil, then as a feminist.” I’ve enjoyed two of Caldwell’s previous books, especially

Bright Precious Thing: A Memoir by Gail Caldwell [July 7, Random House] “In a voice as candid as it is evocative, Gail Caldwell traces a path from her west Texas girlhood through her emergence as a young daredevil, then as a feminist.” I’ve enjoyed two of Caldwell’s previous books, especially  The Fragments of My Father by Sam Mills [July 9, Fourth Estate] A memoir of being the primary caregiver for her father, who had schizophrenia; with references to F. Scott Fitzgerald and Leonard Woolf, who also found themselves caring for people struggling with mental illness. “A powerful and poignant memoir about parents and children, freedom and responsibility, madness and creativity and what it means to be a carer.”

The Fragments of My Father by Sam Mills [July 9, Fourth Estate] A memoir of being the primary caregiver for her father, who had schizophrenia; with references to F. Scott Fitzgerald and Leonard Woolf, who also found themselves caring for people struggling with mental illness. “A powerful and poignant memoir about parents and children, freedom and responsibility, madness and creativity and what it means to be a carer.” Avoid the Day: A New Nonfiction in Two Movements by Jay Kirk [July 28, Harper Perennial] Transylvania, Béla Bartók’s folk songs, an eco-tourist cruise in the Arctic … “Avoid the Day is part detective story, part memoir, and part meditation on the meaning of life—all told with a dark pulse of existential horror.” It was Helen Macdonald’s testimonial that drew me to this: it “truly seems to me to push nonfiction memoir as far as it can go.”

Avoid the Day: A New Nonfiction in Two Movements by Jay Kirk [July 28, Harper Perennial] Transylvania, Béla Bartók’s folk songs, an eco-tourist cruise in the Arctic … “Avoid the Day is part detective story, part memoir, and part meditation on the meaning of life—all told with a dark pulse of existential horror.” It was Helen Macdonald’s testimonial that drew me to this: it “truly seems to me to push nonfiction memoir as far as it can go.” World of Wonders: In Praise of Fireflies, Whale Sharks, and Other Astonishments by Aimee Nezhukumatathil [Aug. 3, Milkweed Editions] “From beloved, award-winning poet Aimee Nezhukumatathil comes a debut work of nonfiction—a collection of essays about the natural world, and the way its inhabitants can teach, support, and inspire us. … Even in the strange and the unlovely, Nezhukumatathil finds beauty and kinship.” Who could resist that title or cover?

World of Wonders: In Praise of Fireflies, Whale Sharks, and Other Astonishments by Aimee Nezhukumatathil [Aug. 3, Milkweed Editions] “From beloved, award-winning poet Aimee Nezhukumatathil comes a debut work of nonfiction—a collection of essays about the natural world, and the way its inhabitants can teach, support, and inspire us. … Even in the strange and the unlovely, Nezhukumatathil finds beauty and kinship.” Who could resist that title or cover? Antlers of Water: Writing on the Nature and Environment of Scotland, edited by Kathleen Jamie [Aug. 6, Canongate] Contributors include Amy Liptrot, musician Karine Polwart and Malachy Tallack. “Featuring prose, poetry and photography, this inspiring collection takes us from walking to wild swimming, from red deer to pigeons and wasps, from remote islands to back gardens … writing which is by turns celebratory, radical and political.”

Antlers of Water: Writing on the Nature and Environment of Scotland, edited by Kathleen Jamie [Aug. 6, Canongate] Contributors include Amy Liptrot, musician Karine Polwart and Malachy Tallack. “Featuring prose, poetry and photography, this inspiring collection takes us from walking to wild swimming, from red deer to pigeons and wasps, from remote islands to back gardens … writing which is by turns celebratory, radical and political.” The Good Ancestor: How to Think Long Term in a Short-Term World by Roman Krznaric [Aug. 27, W.H. Allen] “Drawing on radical solutions from around the world, Krznaric celebrates the innovators who are reinventing democracy, culture and economics so that we all have the chance to become good ancestors and create a better tomorrow.” I’ve been reading a fair bit around this topic. I got a sneak preview of this one from

The Good Ancestor: How to Think Long Term in a Short-Term World by Roman Krznaric [Aug. 27, W.H. Allen] “Drawing on radical solutions from around the world, Krznaric celebrates the innovators who are reinventing democracy, culture and economics so that we all have the chance to become good ancestors and create a better tomorrow.” I’ve been reading a fair bit around this topic. I got a sneak preview of this one from  Eat the Buddha: The Story of Modern Tibet through the People of One Town by Barbara Demick [Sept. 3, Granta / July 28, Random House] “Illuminating a culture that has long been romanticized by Westerners as deeply spiritual and peaceful, Demick reveals what it is really like to be a Tibetan in the twenty-first century, trying to preserve one’s culture, faith, and language.” I read her book on North Korea and found it eye-opening. I’ve read a few books about Tibet over the years; it is fascinating.

Eat the Buddha: The Story of Modern Tibet through the People of One Town by Barbara Demick [Sept. 3, Granta / July 28, Random House] “Illuminating a culture that has long been romanticized by Westerners as deeply spiritual and peaceful, Demick reveals what it is really like to be a Tibetan in the twenty-first century, trying to preserve one’s culture, faith, and language.” I read her book on North Korea and found it eye-opening. I’ve read a few books about Tibet over the years; it is fascinating. Between Light and Storm: How We Live with Other Species by Esther Woolfson [Sept. 3, Granta] “Woolfson considers prehistoric human‒animal interaction and traces the millennia-long evolution of conceptions of the soul and conscience in relation to the animal kingdom, and the consequences of our belief in human superiority.” I’ve read two previous nature books by Woolfson and have done some recent reading around deep time concepts. This is sure to be a thoughtful and nuanced take.

Between Light and Storm: How We Live with Other Species by Esther Woolfson [Sept. 3, Granta] “Woolfson considers prehistoric human‒animal interaction and traces the millennia-long evolution of conceptions of the soul and conscience in relation to the animal kingdom, and the consequences of our belief in human superiority.” I’ve read two previous nature books by Woolfson and have done some recent reading around deep time concepts. This is sure to be a thoughtful and nuanced take.

The second of Bishop’s four published collections, this mostly dwells on contrasts between city (e.g. “View of the Capitol from the Library of Congress,” “Varick Street” and “Letter to N.Y.”) and coastal locations (e.g. “The Bight,” “At the Fishhouses” and “Cape Breton”). The three most memorable poems for me were the title one, which opens the book; “The Prodigal,” a retelling of the Prodigal Son parable; and “Invitation to Miss Marianne Moore” (“From Brooklyn, over the Brooklyn Bridge, on this fine morning, please come flying,” with those last three words recurring at the end of each successive stanza; also note the sandpipers – one of her most famous poems was “Sandpiper,” from 1965’s Questions of Travel). I find that I love particular lines or images from Bishop’s poetry but not her overall style.

The second of Bishop’s four published collections, this mostly dwells on contrasts between city (e.g. “View of the Capitol from the Library of Congress,” “Varick Street” and “Letter to N.Y.”) and coastal locations (e.g. “The Bight,” “At the Fishhouses” and “Cape Breton”). The three most memorable poems for me were the title one, which opens the book; “The Prodigal,” a retelling of the Prodigal Son parable; and “Invitation to Miss Marianne Moore” (“From Brooklyn, over the Brooklyn Bridge, on this fine morning, please come flying,” with those last three words recurring at the end of each successive stanza; also note the sandpipers – one of her most famous poems was “Sandpiper,” from 1965’s Questions of Travel). I find that I love particular lines or images from Bishop’s poetry but not her overall style.  As a seasonal anthology, this falls short by comparison to the Wildlife Trust’s

As a seasonal anthology, this falls short by comparison to the Wildlife Trust’s

When I saw Lucy Jones speak at an event in Hungerford in support of her new book, Losing Eden, early last month, I was intrigued to hear her say that her work was consciously patterned on Silent Spring – right down to the same number of chapters. This prompted me to finally pick up the copy of Carson’s classic that I got free during a cull at the library where I used to work and have a skim through.

When I saw Lucy Jones speak at an event in Hungerford in support of her new book, Losing Eden, early last month, I was intrigued to hear her say that her work was consciously patterned on Silent Spring – right down to the same number of chapters. This prompted me to finally pick up the copy of Carson’s classic that I got free during a cull at the library where I used to work and have a skim through. A seasonal diary that runs from one spring to the next, this is a peaceful book about living alone yet finding community with wildlife and fellow country folk. I took nine months over reading it, keeping it as a bedside book.

A seasonal diary that runs from one spring to the next, this is a peaceful book about living alone yet finding community with wildlife and fellow country folk. I took nine months over reading it, keeping it as a bedside book. Despite being a birdwatcher since childhood, Smyth had always been ambivalent about birdsong. He certainly wasn’t one of those whizzes who can identify any bird by its call; in fact, he needed convincing that bird vocalizations are inherently beautiful. So he set off to answer a few questions: Why do birds sing? How can we recognize them by their songs? And how have these songs played into the human‒bird relationship throughout history? Ranging from bird anatomy to poetry, his historical survey is lighthearted reading that was perfect for the early days of spring. There are also chapters on captive birds, the use of birdsong in classical music, and the contribution birds make to the British soundscape. A final section, more subdued and premonitory in the vein of Silent Spring, imagines a world without birdsong and “the diminution that we all suffer. … Our lives become less rich.” (The title phrase is how Gilbert White described the blackcap’s song, Smyth’s favorite.)