Spring Reads, Part II: Blossomise, Spring Chicken & Cold Spring Harbor

Our garden is an unruly assortment of wildflowers, rosebushes, fruit trees and hedge plants, along with an in-progress pond, and we’ve made a few half-hearted attempts at planting vegetable seeds and flower bulbs. It felt more like summer earlier in May, before we left for France; as the rest of the spring plays out, we’ll see if the beetroot, courgettes, radishes and tomatoes amount to anything. The gladioli have certainly been shooting for the sky!

I recently encountered spring (if only in name) through these three books, a truly mixed bag: a novelty poetry book memorable more for the illustrations than for the words, a fascinating popular account of the science of ageing, and a typically depressing (if you know the author, anyway) novel about failing marriages and families. Part I of my Spring Reading was here.

Blossomise by Simon Armitage; illus. Angela Harding (2024)

Armitage has been the Poet Laureate for yonks now, but I can’t say his poetry has ever made much of an impression on me. That’s especially true of this slim volume commissioned by the National Trust: it’s 3 stars for Angela Harding’s lovely if biologically inaccurate (but I’ll be kind and call them whimsical) engravings, and 2 stars for the actual poems, which are light on content. Plum, cherry, apple, pear, blackthorn and hawthorn blossom loom large. It’s hard to describe spring without resorting to enraptured clichés, though: “Planet Earth in party mode, / petals fizzing and frothing / like pink champagne.” The haiku (11 of 21 poems) feel particularly tossed-off: “The streets are learning / the language of plum blossom. / The trees have spoken.” But others are sure to think more of this than I did.

Armitage has been the Poet Laureate for yonks now, but I can’t say his poetry has ever made much of an impression on me. That’s especially true of this slim volume commissioned by the National Trust: it’s 3 stars for Angela Harding’s lovely if biologically inaccurate (but I’ll be kind and call them whimsical) engravings, and 2 stars for the actual poems, which are light on content. Plum, cherry, apple, pear, blackthorn and hawthorn blossom loom large. It’s hard to describe spring without resorting to enraptured clichés, though: “Planet Earth in party mode, / petals fizzing and frothing / like pink champagne.” The haiku (11 of 21 poems) feel particularly tossed-off: “The streets are learning / the language of plum blossom. / The trees have spoken.” But others are sure to think more of this than I did.

A favourite passage: “Scented and powdered / she’s staging / a one-tree show / with hi-viz blossoms / and lip-gloss petals; / she’ll season the pavements / and polished stones / with something like snow.” (Public library) ![]()

Spring Chicken: Stay Young Forever (or Die Trying) by Bill Gifford (2015)

Gifford was in his mid-forties when he undertook this quirky journey into the science and superstitions of ageing. As a starting point, he ponders the differences between his grandfather, who swam and worked his orchard until his death from infection at 86, and his great-uncle, not so different in age, who developed Alzheimer’s and died in a nursing home at 74. Why is the course of ageing so different for different people? Gifford suspects that, in this case, it had something to do with Uncle Emerson’s adherence to the family tradition of Christian Science and refusal to go to the doctor for any medical concern. (An alarming fact: “The Baby Boom generation is the first in centuries that has actually turned out to be less healthy than their parents, thanks largely to diabetes, poor diet, and general physical laziness.”) But variation in healthspan is still something of a mystery.

Gifford was in his mid-forties when he undertook this quirky journey into the science and superstitions of ageing. As a starting point, he ponders the differences between his grandfather, who swam and worked his orchard until his death from infection at 86, and his great-uncle, not so different in age, who developed Alzheimer’s and died in a nursing home at 74. Why is the course of ageing so different for different people? Gifford suspects that, in this case, it had something to do with Uncle Emerson’s adherence to the family tradition of Christian Science and refusal to go to the doctor for any medical concern. (An alarming fact: “The Baby Boom generation is the first in centuries that has actually turned out to be less healthy than their parents, thanks largely to diabetes, poor diet, and general physical laziness.”) But variation in healthspan is still something of a mystery.

Over the course of the book, Gifford meets all number of researchers and cranks as he attends conferences, travels to spend time with centenarians and scientists, and participates in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. There have been some truly zany ideas about how to pause or reverse aging, such as self-dosing with hormones (Suzanne Somers is one proponent), but long-term use is discouraged. Some things that do help, to an extent, are calorie restriction and periodic fasting plus, possibly, red wine, coffee and aspirin. But the basic advice is nothing we don’t already know about health: don’t eat too much and exercise, i.e., avoid obesity. The layman-interpreting-science approach reminded me of Mary Roach’s. There was some crossover in content with Mark O’Connell’s To Be a Machine and various books I’ve read about dementia. Fun and enlightening. (New purchase – bargain book from Dollar Tree, Bowie, MD) ![]()

Cold Spring Harbor by Richard Yates (1986)

Cold Spring Harbor is a Long Island hamlet whose name casts an appropriately chilly shadow over this slim novel about families blighted by alcoholism and poor decisions. Evan Shepard, only in his early twenties, already has a broken marriage behind him after a teenage romance led to an unplanned pregnancy. Mary and their daughter Kathleen seem to be in the rearview mirror as he plans to return to college for an engineering degree. One day he accompanies his father into New York City for an eye doctor appointment and the car breaks down. The men knock on a random door and thereby become entwined with the Drakes: Gloria, the unstable, daytime-drinking mother; Rachel, her beautiful daughter; and Phil, her earnest but unconfident adolescent son.

Cold Spring Harbor is a Long Island hamlet whose name casts an appropriately chilly shadow over this slim novel about families blighted by alcoholism and poor decisions. Evan Shepard, only in his early twenties, already has a broken marriage behind him after a teenage romance led to an unplanned pregnancy. Mary and their daughter Kathleen seem to be in the rearview mirror as he plans to return to college for an engineering degree. One day he accompanies his father into New York City for an eye doctor appointment and the car breaks down. The men knock on a random door and thereby become entwined with the Drakes: Gloria, the unstable, daytime-drinking mother; Rachel, her beautiful daughter; and Phil, her earnest but unconfident adolescent son.

Evan and Rachel soon marry and agree to Gloria’s plan of sharing a house in Cold Spring Harbor, where the Shepards live (Evan’s mother is also an alcoholic, but less functional; she hides behind the “invalid” label). Take it from me: living with your in-laws is never a good idea! As the Second World War looms, and with Evan and Rachel expecting a baby, it’s clear something will have to give with this uneasy family arrangement, but the dramatic break I was expecting – along the lines of a death or accident – never arrived. Instead, there’s just additional slow crumbling, and the promise of greater suffering to come. Although Yates’s character portraits are as penetrating as in Easter Parade, I found the plot a little lacklustre here. (Secondhand – Clutterbooks, Sedbergh) ![]()

Any ‘spring’ reads for you recently?

Scottish Travels & Book Haul: Wigtown, Arran, Islay and Glasgow

When I was a kid, one-week vacations were rare and precious – Orlando or Raleigh for my dad’s church conferences, summer camp in Amish-country Pennsylvania, spring break with my sister in California – and I mourned them when they were over. As an adult, I find that after a week I’m ready to be home … and yet just days after we got back from Scotland, I’m already wondering why I thought everyday life was so great. Oh well. I like to write up my holidays because otherwise it’s all too easy to forget them. This one had fixed start and end points – several days of beetle recording in Galloway for my husband; meeting up with my sister and nephew in Glasgow one evening the next week – and we filled in the intervening time with excursions to two new-to-us Scottish islands; we’re slowly collecting them all.

First Stop, Wigtown

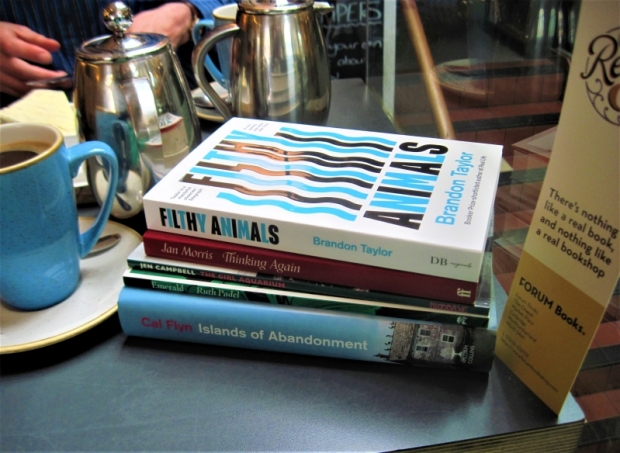

Hard to believe it had been over five years since our first trip to Wigtown. The sleepy little town had barely changed; a couple of bookshops had closed, but there were a few new ones I didn’t remember from last time. The weather was improbably good, sunny and warm enough that I bought a pair of cutoffs at the Community Shop. Each morning my husband set off for bog or beach or wood for his fieldwork and I divided the time until he got back between bits of paid reviewing, reading and book shopping. Our (rather spartan) Airbnb apartment was literally a minute’s walk into town and so was a perfect base.

I paced myself and parcelled out the eight bookshops and several other stores that happen to sell books across the three and a bit days that I had. It felt almost like living there – except I would have to ration my Reading Lasses visits, as a thrice-weekly coffee-and-cake habit would soon get expensive as well as unhealthy. (I spent more on books than on drinks and cakes over the week, though only ~25% more: £44 vs. £32.)

I also had the novelty of seeing my husband interact with his students when we were invited to a barbecue at one’s family home on the Mull of Galloway – and realizing that we’re almost certainly closer in age to the mum than to the student. Getting there required two rural bus journeys to the middle of nowhere, an experience all in itself.

‘Pro’ tips: New Chapter Books was best for bargains, with sections for 50p and £1 paperbacks and free National Geographics. Well-Read Books was good for harder-to-find fiction: among my haul were two Jane Urquhart novels, and the owner was knowledgeable and pleasant. Byre Books carries niche subjects and has scant opening hours, but I procured two poetry collections and a volume of Dorothy Wordsworth’s journals. The Old Bank Bookshop and The Bookshop are the two biggest shops; wander for an hour or more if you can. The Open Book tends to get castoffs from other shops and withdrawn library stock, but I still made two purchases and ended up being the first customer for the week’s hosts: Debbie and Jenny, children’s book authors and long-distance friends from opposite coasts of the USA. Overall, I was pleased with my novella, short story and childhood memoir acquisitions. A better haul than last time.

‘Celebrity’ sightings: On our walk down to the bird hide on the first evening, we passed Jessica Fox, an American expat who’s been influential in setting up the literary festival and The Open Book. She gave us a cheery “hello.” I also spotted Ben of The Bookshop Band twice, once in Reading Lasses and another time on his way to the afternoon school run. Both times he had the baby in tow and I decided not to bother him, not even to introduce myself as one of their Patreon supporters.

On our last morning in town, we lucked out and found Shaun Bythell behind the counter at The Bookshop. He’d just taken delivery of a book-print kilt his staff surprised him by ordering with his credit card, and Nicky (not as eccentric as she’s portrayed in Diary of a Bookseller; she’s downright genteel, in fact) had him model it. He posted a video to Facebook that includes The Open Book hosts on the 23rd, if you wish to see it, and his new cover photo shows him and his staff members wearing the jackets that match the kilt. I bought a few works of paperback fiction and then got him to sign my own copies of two of his books.

As last time, he was chatty and polite, taking an interest in our travels and exhorting us to come back sooner than five years next time. I congratulated him on his success and asked if we could expect more books. He said that depends on his publisher, who worry the market is saturated at the moment, though he has another SIX YEARS of diaries in draft form and the Remainders of the Day epilogue would be quite different if he wrote it now. Tantalizing!

Note to self: Next time, plan to be in town through a Friday evening – we left at noon, so I was sad to miss out on a Beth Porter (the other half of The Bookshop Band) children’s songs concert at Foggie Toddle Books at 3:00, followed by a low-key cocktail party at The Open Book at 5:30 – but not until a Monday, as pretty much everything shuts that day. How I hope someone buys Reading Lasses (the owner is retiring) and maintains the café’s high standard!

Appropriate reading: I read the first third of Dorothy L. Sayers’s The Five Red Herrings because it’s set in the area (first line: “If one lives in Galloway, one either fishes or paints”), and found it entertaining, though not enough to care whodunnit. In general, I’m terrible for trying mystery series and DNFing or giving up after the first book. Lord Peter Wimsey seemed like he’d be an amusing detective in the Sherlock Holmes vein, but the rendering of Scottish accents was OTT and the case relied too much on details of train schedules and bicycles.

Appropriate reading: I read the first third of Dorothy L. Sayers’s The Five Red Herrings because it’s set in the area (first line: “If one lives in Galloway, one either fishes or paints”), and found it entertaining, though not enough to care whodunnit. In general, I’m terrible for trying mystery series and DNFing or giving up after the first book. Lord Peter Wimsey seemed like he’d be an amusing detective in the Sherlock Holmes vein, but the rendering of Scottish accents was OTT and the case relied too much on details of train schedules and bicycles.

Arran

Our short jaunt to Arran started off poorly with a cancelled ferry sailing, leaving us stranded in Ardrossan (which Bythell had almost prophetically dubbed a “sh*thole” that morning!) for several hours until the next one, and we struggled with a leaky rear tyre and showery weather for much of the time, but we were still enamoured with this island that calls itself “Scotland in miniature.” That was particularly delightful for me because I come from the state nicknamed “America in miniature,” Maryland. This Airbnb was plush by comparison, we obtained excellent food from the Blackwater Bakehouse and a posh French takeaway, and we enjoyed walks at the Machrie stone circles and Brodick Castle as well as at the various bays (one with a fossilized dinosaur footprint) that we stopped off at on our driving tour.

Appropriate reading: The Legacy of Elizabeth Pringle by Kirsty Wark, the only Arran-set novel on my library’s catalogue, is an enjoyable dual-timeline story linked by the Lamlash home of the title character. When she died in her nineties in 2006, she bequeathed her home to a kind woman who used to walk past on summer holidays with her daughter in a pram. Martha Morrison was that baby, and with her mother, Anna, suffering from dementia, it’s up to her to take possession and root out Elizabeth’s secrets. Every other chapter is a first-person fragment from Elizabeth’s memoir, cataloguing her losses of parents and lovers and leading ever closer to the present, when she befriended Saul, an American Buddhist monk based at Holy Island across the water, and Niall, a horticulturist at Brodick Castle. It’s a little too neat how the people in her life pair off (sub-Maggie O’Farrell; more Joanna Trollope, perhaps), but it was fun to be able to visualize the settings and to learn about Arran’s farming traditions and wartime history.

Appropriate reading: The Legacy of Elizabeth Pringle by Kirsty Wark, the only Arran-set novel on my library’s catalogue, is an enjoyable dual-timeline story linked by the Lamlash home of the title character. When she died in her nineties in 2006, she bequeathed her home to a kind woman who used to walk past on summer holidays with her daughter in a pram. Martha Morrison was that baby, and with her mother, Anna, suffering from dementia, it’s up to her to take possession and root out Elizabeth’s secrets. Every other chapter is a first-person fragment from Elizabeth’s memoir, cataloguing her losses of parents and lovers and leading ever closer to the present, when she befriended Saul, an American Buddhist monk based at Holy Island across the water, and Niall, a horticulturist at Brodick Castle. It’s a little too neat how the people in her life pair off (sub-Maggie O’Farrell; more Joanna Trollope, perhaps), but it was fun to be able to visualize the settings and to learn about Arran’s farming traditions and wartime history.

Islay

Islay is a tourist mecca largely because of its nine distilleries – what a pity we don’t care for whiskey! – but we sought it out for its wildlife and scenery, which were reminiscent of what we saw in the Outer Hebrides last year. Our B&B was a bit fusty (there was a rotary phone in the hall!), but we had an unbeatable view from our window and enjoyed visiting two RSPB reserves. The highlight for me was the walk to the Mull of Oa peninsula and the cow-guarded American Monument, which pays tribute to the troops who died in two 1918 naval disasters – a torpedoed boat and a shipwreck – and the heroism of locals who rescued survivors.

We spent a very rainy Tuesday mooching from one distillery shop to another. There are two gin-makers whose products we were eager to taste, but we also relished our mission to buy presents for two landmark birthdays, one of an American friend who’s a whiskey aficionado. Even having to get the tyre replaced didn’t ruin the day. There’s drink aplenty on Islay, but quality food was harder to acquire, so if we went back we’d plump for self-catering.

Incidental additional hauls: I found this 50th anniversary Virago tote bag under a bench at Bowmore harbour after our meal at Peatzeria. I waited a while to see if anyone would come back for it, but it was so sodden and sandy that it must have been there overnight. I cleaned it up and brought home additional purchases in it: two secondhand finds at a thrift store in Tarbert, the first town back on the mainland, and a Knausgaard book I got free with my card points from a Waterstones in Glasgow.

Glasgow

My 15-year-old nephew is currently on a school trip to Scotland and my sister went along as an unofficial chaperone. I couldn’t let them come to the UK without meeting up, so for months we’d pencilled in an evening in Glasgow. When we booked our Airbnb room in a suburb, it was because it was on a super-convenient train line … which happened to be closed for engineering works while we were there. Plan B: rail replacement buses, which were fine. We greatly enjoyed the company of Santos the Airbnb cat, who mugged us for scraps of our breakfasts.

My 15-year-old nephew is currently on a school trip to Scotland and my sister went along as an unofficial chaperone. I couldn’t let them come to the UK without meeting up, so for months we’d pencilled in an evening in Glasgow. When we booked our Airbnb room in a suburb, it was because it was on a super-convenient train line … which happened to be closed for engineering works while we were there. Plan B: rail replacement buses, which were fine. We greatly enjoyed the company of Santos the Airbnb cat, who mugged us for scraps of our breakfasts.

With our one day in Glasgow, we decided to prioritize the Burrell Collection, due to the enthusiastic recommendations from Susan, our Arran hosts, and Bill Bryson in Notes on a Small Island (“Among the city’s many treasures, none shines brighter, in my view”). It’s a museum with a difference, housed in a custom-built edifice that showcases the wooded surroundings as much as the stunning objects. We were especially partial to the stained glass.

Our whistle-stop city tour also included a walk past the cathedral, a ramble through the Necropolis (where, pleasingly, I saw a grave for one Elizabeth Pringle), and the Tenement Museum, a very different sort of National Trust house that showed how one woman, a spinster and hoarder, lived in the first half of the 20th century. Then on to an exceptional seafood-heavy meal at Kelp, also recommended by Susan, and an all-too-brief couple of hours with my family at their hotel and a lively pub.

We keep returning to Scotland. Where next in a few years? Possibly the southern islands of the Outer Hebrides, which we didn’t have time for last year, or the more obscure of the Inner Hebrides, before planning return visits to some favourites. All the short ferry rides were smooth this time around, so I can cope with the thought of more.

We got home to find our mullein plants attempting to take over the world.

Thomas Hardy Tourism in Dorset

We fancied a short break before term starts (my husband is a teaching associate in university-level biology), so booked a cheap Airbnb room in Bridport for a couple of nights and headed to Dorset on Wednesday, stopping at the Thomas Hardy birthplace cottage on the way down and returning on Friday via Max Gate, the home he designed on the outskirts of Dorchester.

I’d been to both before, but over 15 years ago. In the summer of 2004, at the end of my study abroad year, I used a travel grant from my college to spend a week in Dorset and Nottinghamshire, researching the sense of place in the works of Hardy and D.H. Lawrence. I marvel at my bravery now: barely out of my teens, there I was traveling alone by train and bus to places I’d never been before, finding my own B&B accommodation, and taking long countryside walks to arrive at many sites on foot.

Max Gate

I found that much had changed in 15 years. The main difference is that both properties have now been given the full National Trust treatment, with an offsite visitor centre and café down the lane from Hardy’s Cottage, and the upper floors of Max Gate now open to the public after the end of private tenancies in 2011.* This could be perceived as a good thing or a bad thing: Everything is more commercial and geared towards tourists, yes, but also better looked after and more inviting thanks to visitor income and knowledgeable volunteers. Fifteen years ago I remember the two sites being virtually deserted, with the cottage’s garden under black plastic and awaiting a complete replanting. Now it’s flourishing with flowers and vegetables.

*In 2004 only a few ground-floor rooms were open to the public. I happened to spot in the visitor’s book that novelist Vikram Seth had signed in just before me. When I made the caretakers aware of this, they expressed admiration for his work and offered him an exclusive look at the study where Hardy wrote Tess of the d’Urbervilles. I got to tag along! The story is less impressive since it’s been a standard part of the house tour for eight years now, but I still consider it a minor claim to fame.

The thatched cottage doesn’t possess anything that belonged to the Hardy family, but is decorated in a period style that’s true to its mid-1800s origin. Hardy was born here and remained until his early thirties, completing an architecture apprenticeship and writing his first few books, including Under the Greenwood Tree. Even if you’re not particularly familiar with or fond of Hardy’s work, I’d recommend an afternoon at the cottage for a glimpse of how simple folk lived in that time. With wood smoke spooling out of the chimney and live music emanating from the door – there are two old fiddles in the sitting room that guests are invited to play – it was a perfectly atmospheric visit.

Afterwards, we headed to Portland, an isthmus extending from the south coast near Weymouth and known for its stone. It’s the setting of The Well-Beloved, which Hardy issued in serial form in 1892 and revised in 1897 for its book publication. Jocelyn Pierston, a sculptor whose fame is growing in London, returns to “the Isle of Slingers” (Hardy gave all his English locales made-up names) for a visit and runs into Avice Caro, a childhood friend. On a whim, he asks her to marry him. Before long, though, following a steamy (for Victorian literature, anyway) scene under an upturned boat during a storm, he transfers his affections to Miss Bencomb, the daughter of his father’s rival stone merchant. The fickle young man soon issues a second marriage proposal. I read the first 30 pages, but that was enough for me.

Afterwards, we headed to Portland, an isthmus extending from the south coast near Weymouth and known for its stone. It’s the setting of The Well-Beloved, which Hardy issued in serial form in 1892 and revised in 1897 for its book publication. Jocelyn Pierston, a sculptor whose fame is growing in London, returns to “the Isle of Slingers” (Hardy gave all his English locales made-up names) for a visit and runs into Avice Caro, a childhood friend. On a whim, he asks her to marry him. Before long, though, following a steamy (for Victorian literature, anyway) scene under an upturned boat during a storm, he transfers his affections to Miss Bencomb, the daughter of his father’s rival stone merchant. The fickle young man soon issues a second marriage proposal. I read the first 30 pages, but that was enough for me.

St. George’s Church, Portland, in a Christopher Wren style.

[I failed on classics or doorstoppers this month, alas, so look out for these monthly features to return in October. I did start The Warden by Anthony Trollope, my first of his works since Phineas Finn in 2005, with the best of intentions, and initially enjoyed the style – partway between Dickens and Hardy, and much less verbose than Trollope usually is. However, I got bogged down in the financial details of Septimus Harding’s supposed ripping-off of the 12 old peasants who live in the local hospital (as in a rest center for the aged and infirm, like the Hospital of St Cross at Winchester). He never should have had his comfortable £800 a year, it seems. His son-in-law, the archdeacon Dr. Grantly, and his would-be son-in-law, gadfly John Bold, take opposing sides as Harding looks to the legal and religious authorities for advice. I read the first 125 pages but only briefly skimmed the rest. Given how much longer the other five volumes are, I doubt I’ll ever read the rest of the Barchester Chronicles.]

[I failed on classics or doorstoppers this month, alas, so look out for these monthly features to return in October. I did start The Warden by Anthony Trollope, my first of his works since Phineas Finn in 2005, with the best of intentions, and initially enjoyed the style – partway between Dickens and Hardy, and much less verbose than Trollope usually is. However, I got bogged down in the financial details of Septimus Harding’s supposed ripping-off of the 12 old peasants who live in the local hospital (as in a rest center for the aged and infirm, like the Hospital of St Cross at Winchester). He never should have had his comfortable £800 a year, it seems. His son-in-law, the archdeacon Dr. Grantly, and his would-be son-in-law, gadfly John Bold, take opposing sides as Harding looks to the legal and religious authorities for advice. I read the first 125 pages but only briefly skimmed the rest. Given how much longer the other five volumes are, I doubt I’ll ever read the rest of the Barchester Chronicles.]

My other appropriate reading of the trip was Moon Tiger by Penelope Lively, in which Claudia Hampton, a popular historian now on her deathbed, excavates the layers of her personal past and dwells on the subjectivity of history and memory. She grew up in Dorset and mentions ammonites and rock strata, which we encountered on our beach walks.

Bridport isn’t so well known, but we thought it a lovely place, full of pleasant cafés, pubs and charity shops. It also has an independent bookshop and two secondhand ones, and we had an excellent meal of dumplings and noodle bowls at the English/Asian fusion restaurant Dorshi. It’s tucked away down an alley, but well worth a special trip. Our other special experience of the trip was a tour of Dorset Nectar, a small, family-run organic cider farm just outside of Bridport, which included a tasting of their 10+ delicious ciders. We had splendid late-summer weather for our three days away, too – we really couldn’t have asked for better.

Three secondhand books purchased, for a total of £4.10.

Stanley and Elsie by Nicola Upson & A Visit to Sandham Memorial Chapel

“I don’t want them to look like war paintings, Elsie. I want them to look like heaven.”

When I was offered a copy of this novel to review as part of the blog tour, I was unfamiliar with the name of its subject, the artist Sir Stanley Spencer (1891–1959) – until I realized that he painted the WWI-commemorative Sandham Memorial Chapel in Hampshire, which I had never visited* but knew was just 5.5 miles from our home in Berkshire.

Take another look at the title, though: two characters are given double billing, the second of whom is Elsie Munday, who in the opening chapter presents herself for an interview with Stanley and his wife, Hilda (also a painter), who promptly hire her to be their housemaid at Chapel View in 1928. This creates a setup similar to that in Girl with a Pearl Earring, with a lower-class character observing the inner workings of an artist’s household and giving plain-speaking commentary on what she sees. Upson’s close third-person narration sticks with Elsie for the whole of Part I, but in Part II the picture widens out, with the point of view rotating between Hilda, Elsie and Dorothy Hepworth, the reluctant third side in a love triangle that develops between Stanley and her partner, Patricia Preece.

Hilda and Stanley argue about everything, from childrearing to art: they even paint dueling portraits of Elsie – with Hilda’s Country Girl winning out. Elsie knows she’s lucky to have such a comfortable position with the Spencers and their daughters at Burghclere, and later at Cookham, but she’s uneasy at how Stanley turns her into a confidante in his increasingly tempestuous marriage. Hilda, frustrated at Stanley’s selfish, demanding ways, often returns to her family home in Hampstead, leaving Elsie alone with her employer. Stanley doesn’t give a fig for local opinion, but Elsie knows she has a reputation to protect – especially considering that her moments alone with Stanley aren’t entirely free of sexual tension.

I love reading about artists’ habits – how creative work actually gets done – so I particularly loved the scenes where Elsie, sent on errands, finds Stanley up a ladder in the chapel, pondering how to get a face or object just right. On more than one occasion he borrows her kitchen items, such as a sponge and cooked and uncooked rashers of bacon, so he can render them perfectly in his paintings. I also loved that this is a local interest book for me, with Newbury, where I live, mentioned four or five times in passing as the nearest big town. Part II, with its account of Stanley’s extramarital doings becoming ever more sordid, didn’t grip me as much as Part I, but I found the whole to be an elegantly written study of a very difficult man and the ties that he made and broke over the course of several decades.

I love reading about artists’ habits – how creative work actually gets done – so I particularly loved the scenes where Elsie, sent on errands, finds Stanley up a ladder in the chapel, pondering how to get a face or object just right. On more than one occasion he borrows her kitchen items, such as a sponge and cooked and uncooked rashers of bacon, so he can render them perfectly in his paintings. I also loved that this is a local interest book for me, with Newbury, where I live, mentioned four or five times in passing as the nearest big town. Part II, with its account of Stanley’s extramarital doings becoming ever more sordid, didn’t grip me as much as Part I, but I found the whole to be an elegantly written study of a very difficult man and the ties that he made and broke over the course of several decades.

For the tone as well as the subject matter, I would particularly recommend it to readers of Jonathan Smith’s Summer in February and Graham Swift’s Mothering Sunday, and especially Esther Freud’s Mr. Mac and Me.

My rating:

Stanley and Elsie will be published by Duckworth on May 2nd. My thanks to the publisher for the proof copy for review. They also sent a stylish tote bag!

Nicola Upson

Nicola Upson is best known for her seven Josephine Tey crime novels. She has also published nonfiction, including a book on the sculpture of Helaine Blumenfeld. This is her first stand-alone novel.

*Until now. On a gorgeous Easter Saturday that felt more like summer than spring, I had my husband drop me off on his way to a country walk so I could tour the chapel. I appreciated Spencer’s “holy box” so much more having read the novel than I ever could have otherwise – even though the paintings were nothing like I’d imagined from Upson’s descriptions.

You enter the chapel through the wooden double doors at the center.

What struck me immediately is that, for war art, the focus is so much more on domesticity. Spencer briefly served in Salonika, Macedonia (like his patrons’ brother, Harry Sandham, to whose memory the chapel is dedicated), but had initially been rejected by the army and started off as a medical orderly in an English hospital. Both Salonika and Beaufort hospital appear in the paintings, but there are no battle scenes or bloody injuries. Instead we see tableaux of cooking, doing laundry, making beds, inventorying kitbags, filling canteens, reading maps, dressing under mosquito nets and making stone mosaics. It’s as if Spencer wanted to spotlight what happens in between the fighting. These everyday activities would have typified the soldiers’ lives more than active combat, after all.

I was reminded of how Stanley explains his approach in the novel:

“There’s something heroic in the everyday, don’t you think?”

“Isn’t that what peace is sometimes? A succession of bland moments? We have to cherish them, though, otherwise what was the point of fighting for them?”

The paintings show inventive composition but are in an unusual style that sometimes verges on the grotesque. Many of the figures are lumpen and childlike, especially in Tea in the Hospital Ward, where the soldiers scoffing bread and jam look like cheeky schoolboys. There are lots of animals on display, especially horses and donkeys, but they often look enormous and not entirely realistic. The longer you look, the more details you spot, like a dog raiding a stash of Fray Bentos tins and a young man looking at his reflection in a picture frame to part his hair with a comb. These aren’t desolate, burnt-out landscapes but rich with foliage and blossom, even in Macedonia, which recalls the Holy Land and seems timeless.

The central painting behind the altar, The Resurrection of the Soldiers, imagines the dead rising out of their graves, taking up their white crosses and delivering them to Jesus, a white-clad figure in the middle distance. There’s an Italian Renaissance feeling to this one, with one face in particular looking like it could have come straight out of Giotto (an acknowledged influence on Spencer’s chapel work). It’s as busy as Bosch, but not as dark thematically or in terms of the color scheme – while some of the first paintings in the sequence, like the one of scrubbing hospital floors, recall Edward Hopper with their somber realism. We see all these soldiers intact: at their resurrection they are whole, with no horrific wounds or humiliating nudity. Like Stanley says to Elsie, it’s more heaven than war.

If you are ever in the area, I highly recommend even a quick stop at this National Trust property. I showed a few workers my advanced copy of the novel; while the reception staff were unaware of its existence, a manager I caught up with after my tour knew about it and had plans to read it soon. She also said they will stock it in the NT shop on site.

Chastleton House (It Even Has a Bookshop)

I’ve been off my blogging game ever since we got back from America, but I hope to remedy that soon. I have a blog post planned for every day of the coming week, including some reviews, my monthly Library Checkout, a few recommendations for July releases, and a look back at the best books from the first half of the year.

Today I’m easing myself back into blogging with a mini profile of the National Trust historic manor we visited yesterday, Chastleton House in Oxfordshire (but it’s nearer the Gloucestershire border – very much Cotswolds country).

Photo by Chris Foster.

My brother-in-law sent us a voucher for free entry into any NT property, but my eye was drawn to this one in particular because I saw that there’s a secondhand bookshop in the stables. Compared to other historic houses, this one feels a lot less fusty. It’s been preserved as it was when the NT acquired it in 1991, so instead of reconstructed seventeenth-century rooms you get them as they were last used by later tenants. There are cracks in the plasterwork, cobwebs in the corners, and lots of stuff everywhere. But as a result, it seems less like part of the corporate fold; even the “Do Not Touch” signs are handwritten.

Chastleton has a literary claim to fame of which I was unaware before our visit: it was a filming location for the 2015 BBC adaptation of Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall. (Never mind that it was built in 1607–12, well after the Tudor history that novel is meant to portray.) Another interesting historical nugget: this is where the rules of croquet were codified in the 1860s, and there are still croquet lawns there today. Our visit happened to coincide with a special lawn games weekend, so we learned how to play croquet properly and my husband proceeded to trounce me.

Of course, I availed myself of a few bargain books from the secondhand stall.

We also had tea and cake from a charity sale in the next-door churchyard. After dinner back home, in the evening we decided to walk 10 minutes down the road to our local event space for a folk concert featuring The Willows, with Gareth Lee and Annie Baylis supporting. We’ve been to three gigs at this former village hall so far this year; with tickets just £10 each and the venue so close, why not?! Each time we have heard absolutely excellent live folk music, with tinges of everything from Americana to electronica.

We also had tea and cake from a charity sale in the next-door churchyard. After dinner back home, in the evening we decided to walk 10 minutes down the road to our local event space for a folk concert featuring The Willows, with Gareth Lee and Annie Baylis supporting. We’ve been to three gigs at this former village hall so far this year; with tickets just £10 each and the venue so close, why not?! Each time we have heard absolutely excellent live folk music, with tinges of everything from Americana to electronica.

All together, a smashing day out.

Phosphorescence by Julia Baird – An intriguing if somewhat scattered hybrid: a self-help memoir with nature themes. Many female-authored nature books I’ve read recently (Wintering, A Still Life, Rooted) have emphasized paying attention and courting a sense of wonder. To cope with recurring abdominal cancer, Baird turned to swimming at the Australian coast and to faith. Indeed, I was surprised by how deeply she delves into Christianity here. She was involved in the campaign for the ordination of women and supports LGBTQ rights.

Phosphorescence by Julia Baird – An intriguing if somewhat scattered hybrid: a self-help memoir with nature themes. Many female-authored nature books I’ve read recently (Wintering, A Still Life, Rooted) have emphasized paying attention and courting a sense of wonder. To cope with recurring abdominal cancer, Baird turned to swimming at the Australian coast and to faith. Indeed, I was surprised by how deeply she delves into Christianity here. She was involved in the campaign for the ordination of women and supports LGBTQ rights.

Open House by Elizabeth Berg – When her husband leaves, Sam goes off the rails in minor and amusing ways: accepting a rotating cast of housemates, taking temp jobs at a laundromat and in telesales, and getting back onto the dating scene. I didn’t find Sam’s voice as fresh and funny as Berg probably thought it is, but this is as readable as any Oprah’s Book Club selection and kept me entertained on the plane ride back from America and the car trip up to York. It’s about finding joy in the everyday and not defining yourself by your relationships.

Open House by Elizabeth Berg – When her husband leaves, Sam goes off the rails in minor and amusing ways: accepting a rotating cast of housemates, taking temp jobs at a laundromat and in telesales, and getting back onto the dating scene. I didn’t find Sam’s voice as fresh and funny as Berg probably thought it is, but this is as readable as any Oprah’s Book Club selection and kept me entertained on the plane ride back from America and the car trip up to York. It’s about finding joy in the everyday and not defining yourself by your relationships.  Site Fidelity by Claire Boyles – I have yet to review this for BookBrowse, but can briefly tell you that it’s a terrific linked short story collection set on the sagebrush steppe of Colorado and featuring several generations of strong women. Boyles explores environmental threats to the area, like fracking, polluted rivers and an endangered bird species, but never with a heavy hand. It’s a different picture than what we usually get of the American West, and the characters shine. The book reminded me most of Love Medicine by Louise Erdrich.

Site Fidelity by Claire Boyles – I have yet to review this for BookBrowse, but can briefly tell you that it’s a terrific linked short story collection set on the sagebrush steppe of Colorado and featuring several generations of strong women. Boyles explores environmental threats to the area, like fracking, polluted rivers and an endangered bird species, but never with a heavy hand. It’s a different picture than what we usually get of the American West, and the characters shine. The book reminded me most of Love Medicine by Louise Erdrich.

Every Minute Is a Day by Robert Meyer, MD and Dan Koeppel – The Bronx’s Montefiore Medical Center serves an ethnically diverse community of the working poor. Between March and September 2020, it had 6,000 Covid-19 patients cross the threshold. Nearly 1,000 of them would die. Unfolding in real time, this is an emergency room doctor’s diary as compiled from interviews and correspondence by his journalist cousin. (Coming out on August 3rd. Reviewed for Shelf Awareness.)

Every Minute Is a Day by Robert Meyer, MD and Dan Koeppel – The Bronx’s Montefiore Medical Center serves an ethnically diverse community of the working poor. Between March and September 2020, it had 6,000 Covid-19 patients cross the threshold. Nearly 1,000 of them would die. Unfolding in real time, this is an emergency room doctor’s diary as compiled from interviews and correspondence by his journalist cousin. (Coming out on August 3rd. Reviewed for Shelf Awareness.)

Virga by Shin Yu Pai – Yoga and Zen Buddhism are major elements in this tenth collection by a Chinese American poet based in Washington. She reflects on her family history and a friend’s death as well as the process of making art, such as a project of crafting 108 clay reliquary boxes. “The uncarved block,” a standout, contrasts the artist’s vision with the impossibility of perfection. The title refers to a weather phenomenon in which rain never reaches the ground because the air is too hot. (Coming out on August 1st.)

Virga by Shin Yu Pai – Yoga and Zen Buddhism are major elements in this tenth collection by a Chinese American poet based in Washington. She reflects on her family history and a friend’s death as well as the process of making art, such as a project of crafting 108 clay reliquary boxes. “The uncarved block,” a standout, contrasts the artist’s vision with the impossibility of perfection. The title refers to a weather phenomenon in which rain never reaches the ground because the air is too hot. (Coming out on August 1st.)  The Other Black Girl by Zakiya Dalila Harris – I feel like I’m the last person on Earth to read this buzzy book, so there’s no point recounting the plot, which initially is reminiscent of

The Other Black Girl by Zakiya Dalila Harris – I feel like I’m the last person on Earth to read this buzzy book, so there’s no point recounting the plot, which initially is reminiscent of  Heartstopper, Volume 1 by Alice Oseman – It’s well known at Truham boys’ school that Charlie is gay. Luckily, the bullying has stopped and the others accept him. Nick, who sits next to Charlie in homeroom, even invites him to join the rugby team. Charlie is smitten right away, but it takes longer for Nick, who’s only ever liked girls before, to sort out his feelings. This black-and-white YA graphic novel is pure sweetness, taking me right back to the days of high school crushes. I raced through and placed holds on the other three volumes.

Heartstopper, Volume 1 by Alice Oseman – It’s well known at Truham boys’ school that Charlie is gay. Luckily, the bullying has stopped and the others accept him. Nick, who sits next to Charlie in homeroom, even invites him to join the rugby team. Charlie is smitten right away, but it takes longer for Nick, who’s only ever liked girls before, to sort out his feelings. This black-and-white YA graphic novel is pure sweetness, taking me right back to the days of high school crushes. I raced through and placed holds on the other three volumes.  The Vacationers by Emma Straub – Perfect summer reading; perfect holiday reading. Like Jami Attenberg, Straub writes great dysfunctional family novels featuring characters so flawed and real you can’t help but love and laugh at them. Here, Franny and Jim Post borrow a friend’s home in Mallorca for two weeks, hoping sun and relaxation will temper the memory of Jim’s affair. Franny’s gay best friend and his husband, soon to adopt a baby, come along. Amid tennis lessons, swims and gourmet meals, secrets and resentment simmer.

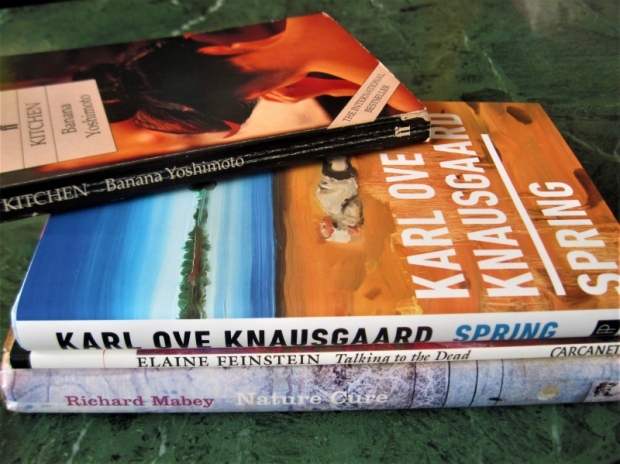

The Vacationers by Emma Straub – Perfect summer reading; perfect holiday reading. Like Jami Attenberg, Straub writes great dysfunctional family novels featuring characters so flawed and real you can’t help but love and laugh at them. Here, Franny and Jim Post borrow a friend’s home in Mallorca for two weeks, hoping sun and relaxation will temper the memory of Jim’s affair. Franny’s gay best friend and his husband, soon to adopt a baby, come along. Amid tennis lessons, swims and gourmet meals, secrets and resentment simmer.  Kitchen by Banana Yoshimoto – A pair of poignant stories of loss and what gets you through. In the title novella, after the death of the grandmother who raised her, Mikage takes refuge with her friend Yuichi and his mother (once father), Eriko, a trans woman who runs a nightclub. Mikage becomes obsessed with cooking: kitchens are her safe place and food her love language. Moonlight Shadow, half the length, repeats the bereavement theme but has a magic realist air as Satsuki meets someone who lets her see her dead boyfriend again.

Kitchen by Banana Yoshimoto – A pair of poignant stories of loss and what gets you through. In the title novella, after the death of the grandmother who raised her, Mikage takes refuge with her friend Yuichi and his mother (once father), Eriko, a trans woman who runs a nightclub. Mikage becomes obsessed with cooking: kitchens are her safe place and food her love language. Moonlight Shadow, half the length, repeats the bereavement theme but has a magic realist air as Satsuki meets someone who lets her see her dead boyfriend again.  This was my 11th book from Padel; I’ve read a mixture of her poetry, fiction, narrative nonfiction and poetry criticism. Emerald consists mostly of poems in memory of her mother, Hilda, who died in 2017 at the age of 97. The book pivots on her mother’s death, remembering the before (family stories, her little ways, moving her into sheltered accommodation when she was 91, sitting vigil at her deathbed) and the letdown of after. It made a good follow-on to one I reviewed last month, Kate Mosse’s

This was my 11th book from Padel; I’ve read a mixture of her poetry, fiction, narrative nonfiction and poetry criticism. Emerald consists mostly of poems in memory of her mother, Hilda, who died in 2017 at the age of 97. The book pivots on her mother’s death, remembering the before (family stories, her little ways, moving her into sheltered accommodation when she was 91, sitting vigil at her deathbed) and the letdown of after. It made a good follow-on to one I reviewed last month, Kate Mosse’s