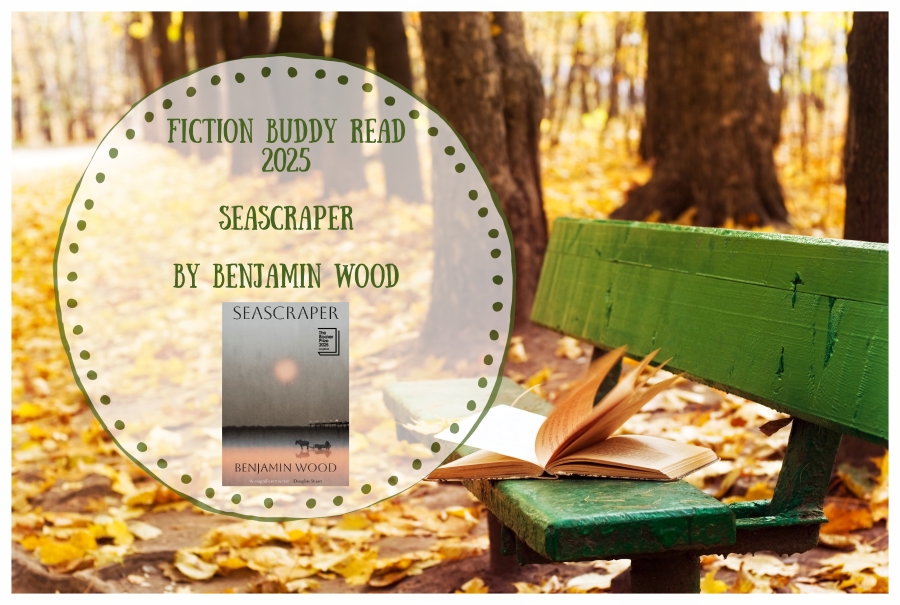

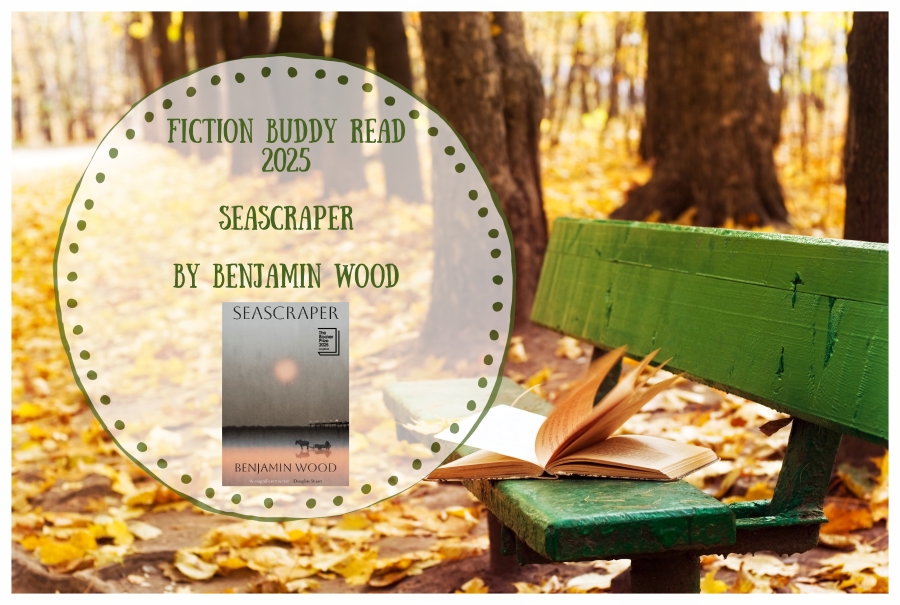

Seascraper by Benjamin Wood (#NovNov25 Buddy Read)

Seascraper is set in what appears to be the early 1960s yet could easily be a century earlier because of the protagonist’s low-tech career. Thomas Flett lives with his mother in fictional Longferry in northwest England and carries on his grandfather’s tradition of fishing with a horse and cart. Each day he trawls the seabed for shrimp – sometimes twice a day when the tide allows – and sells his catch to local restaurants. At around 20 years old, Thomas still lives with his mother, who is disabled by obesity and chronic pain. He’s the sole breadwinner in the household and there’s an unusual dynamic between them in that his mother isn’t all that many years older, having fallen pregnant by a teacher while she was still in school.

Their life is just a mindless trudge of work with cosy patterns of behaviour in between … He wants to wake up every morning with a better purpose.

It’s a humdrum, hardscrabble existence, and Thomas longs for a bigger and more creative life, which he hopes he might achieve through his folk music hobby – or a chance encounter with an American filmmaker. Edgar Acheson is working on a big-screen adaptation of a novel; to save money, it will be filmed here in Merseyside rather than in coastal Maine where it’s set. One day he turns up at the house asking Thomas to be his guide to the sands. Thomas reluctantly agrees to take Edgar out one evening, even though it will mean missing out on an open mic night. They nearly get lost in the fog and the cart starts to sink into quicksand. What follows is mysterious, almost like a hallucination sequence. When Thomas makes it back home safely, he writes an autobiographical song, “Seascraper” (you can listen to a recording on Wood’s website).

After this one pivotal and surprising day, Thomas’s fortunes might just change. This atmospheric novella contrasts subsistence living with creative fulfillment. There is the bitterness of crushed dreams but also a glimmer of hope. Its The Old Man and the Sea-type setup emphasizes questions of solitude, obsession and masculinity. Thomas wishes he had a father in his life; Edgar, even in so short a time frame, acts as a sort of father figure for him. And Edgar is a father himself – he shows Thomas a photo of his daughter. We are invited to ponder what makes a good father and what the absence of one means at different stages in life. Mental and physical health are also crucial considerations for the characters.

That Wood packs all of this into a compact circadian narrative is impressive. My admiration never crossed into warmth, however. I’ve read four of Wood’s five novels and still love his debut, The Bellwether Revivals, most, followed by his second, The Ecliptic. I’ve also read The Young Accomplice, which I didn’t care for as much, so I’m only missing out on A Station on the Path to Somewhere Better now. Wood’s plot and character work is always at a high standard, but his books are so different from each other that I have no clear sense of him as a novelist. Still, I’m pleased that the Booker longlisting has introduced him to many new readers.

Also reviewed by:

Annabel (AnnaBookBel)

Anne (My Head Is Full of Books)

Brona (This Reading Life)

Cathy (746 Books)

Davida (The Chocolate Lady’s Book Review Blog)

Eric (Lonesome Reader)

Jane (Just Reading a Book)

Helen (She Reads Novels)

Kate (Books Are My Favourite and Best)

Kay (What? Me Read?)

Nancy (The Literate Quilter)

Rachel (Yarra Book Club)

Susan (A life in books)

Check out this written interview with Wood (and this video one with Eric of Lonesome Reader) as well as a Q&A on the Booker Prize website in which Wood talks about the unusual situation in which he wrote the book.

(Public library)

[163 pages]

![]()

#NovNov25 Begins! & My Year in Novellas

Welcome to Novellas in November! The link-up is open (see my pinned post). At the start of the month, we’re inviting you to tell us about any novellas you’ve read since last November.

I have a designated shelf of short books that I keep adding to throughout the year. Whenever I’m at secondhand bookshops, charity shops, the Little Free Library, or the public library volunteering, I’m always eyeing up thin volumes and thinking about my piles for November.

But I read novellas other times of year, too. Forty-five of them between December 2024 and now, according to my Goodreads shelves (last year the figure was 44 and the year before it was 46, so that’s my natural average). I often choose to review books of novella length for BookBrowse, Foreword and Shelf Awareness, so that helps to account for the number. I’ve read a real mixture, but predominantly literature in translation and autobiographical works.

My four favourites are ones I’ve already covered on the blog (links to my reviews): The Most by Jessica Anthony, Pale Shadows by Dominique Fortier and Three Days in June by Anne Tyler; and, in nonfiction, Mornings without Mii by Mayumi Inaba. Two works of historical fiction, one contemporary story; and a memoir of life with a cat.

What are some of your recent favourite novellas?

#NovNov25 and Other November Reading Plans

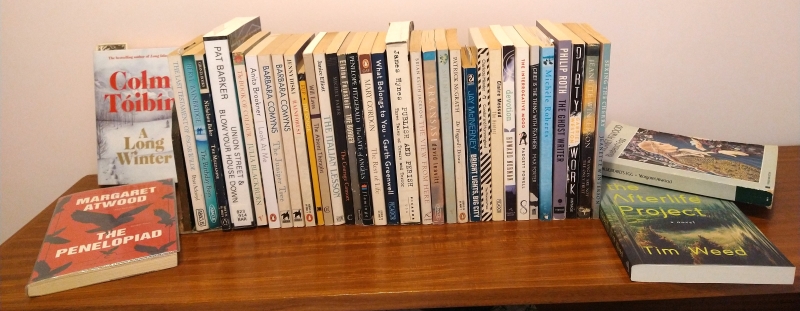

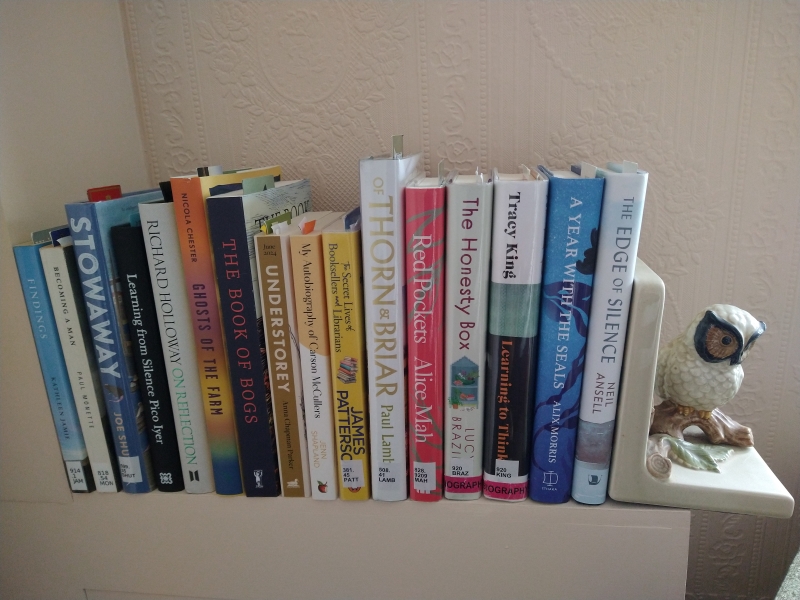

Not much more than two weeks now before Novellas in November (#NovNov25) begins! Cathy and I are getting geared up and making plans for what we’re going to read. I have a handful of novellas out from the library, but mostly I gathered potential reads from my own shelves. I’m hoping to coincide with several of November’s other challenges, too.

Although we’re not using the below as themes this year, I’ve grouped my options into categories:

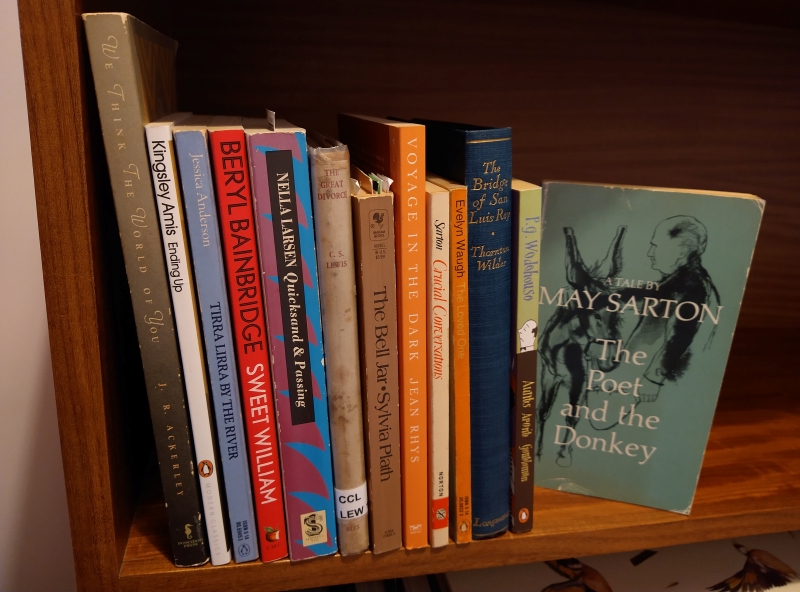

Short Classics (pre-1980)

Just Quicksand to read from the Larsen volume; the Wilder would be a reread.

Contemporary Novellas

(Just Blow Your House Down; and the last two of the three novellas in the Hynes.)

Also, on my e-readers: Sea, Poison by Caren Beilin, Likeness by Samsun Knight, Eradication: A Fable by Jonathan Miles (a 2026 release, to review early for Shelf Awareness)

*Margaret Atwood Reading Month is hosted by Marcie of Buried in Print. I’ve just read The Penelopiad for book club, so I’ll start off with a review of that. I might also reread Bluebeard’s Egg, and I’ll be eagerly awaiting her memoir from the library.

*Margaret Atwood Reading Month is hosted by Marcie of Buried in Print. I’ve just read The Penelopiad for book club, so I’ll start off with a review of that. I might also reread Bluebeard’s Egg, and I’ll be eagerly awaiting her memoir from the library.

[*Science Fiction Month: Beautyland by Marie-Helene Bertino, Archive of Unknown Universes by Ruben Reyes Jr., and The Afterlife Project (all catch-up review books) are options, plus I recently started reading The Martian by Andy Weir.]

Short Nonfiction

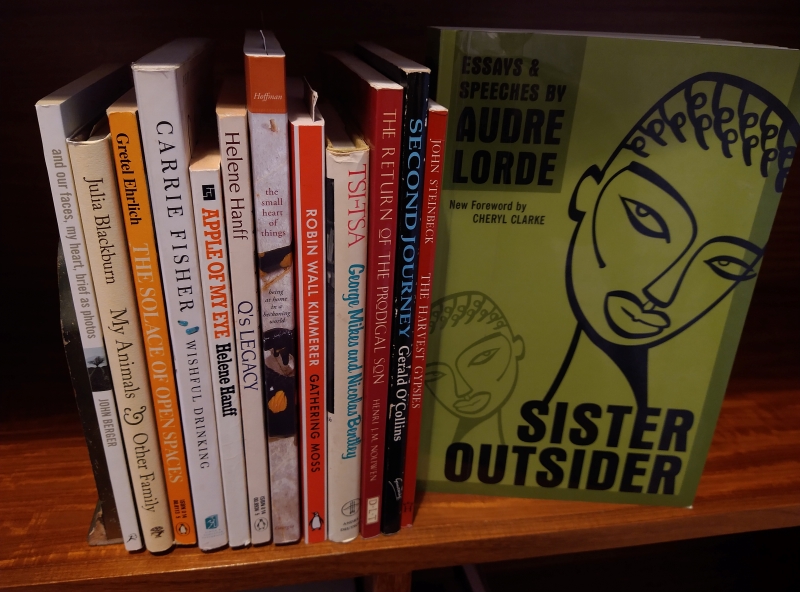

Including our buddy read, Sister Outsider by Audre Lorde. (A shame about that cover!)

Also, on my e-readers: The Serviceberry by Robin Wall Kimmerer, No Straight Road Takes You There by Rebecca Solnit, Because We Must by Tracy Youngblom. And, even though it doesn’t come out until February, I started reading The Irish Goodbye: Micro-Memoirs by Beth Ann Fennelly via Edelweiss.

For Nonfiction November, I also have plenty of longer nonfiction on the go, a mixture of review books to catch up on and books from the library:

I also have one nonfiction November release, Joyride by Susan Orlean, to review.

Novellas in Translation

At left are all the novella-length options, with four German books on top.

The Chevillard and Modiano are review copies to catch up on.

Also on the stack, from the library: Super-Frog Saves Tokyo by Haruki Murakami

On my e-readers: The Old Fire by Elisa Shua Dusapin, The Old Man by the Sea by Domenico Starnone, Our Precious Wars by Perrine Tripier

*German Literature Month: Our recent trip to Berlin and Lübeck whetted my appetite to read more German/German-language fiction. I’ll try to coincide with the Thomas Mann week as I was already planning to reread Death in Venice. I have some longer German books on the right-hand side as well. I started Kairos but found it hard going so might switch to audiobook. I also have Demian by Hermann Hesse on my Nook, downloaded from Project Gutenberg.

*German Literature Month: Our recent trip to Berlin and Lübeck whetted my appetite to read more German/German-language fiction. I’ll try to coincide with the Thomas Mann week as I was already planning to reread Death in Venice. I have some longer German books on the right-hand side as well. I started Kairos but found it hard going so might switch to audiobook. I also have Demian by Hermann Hesse on my Nook, downloaded from Project Gutenberg.

Spy any favourites or a particularly appealing title in my piles?

The link-up is now open for you to share your planning post!

Any novellas lined up to read next month?

Novellas in November 2025 Link-Up (#NovNov25)

Novellas in November 2025 was a roaring success: In total, we had 50 bloggers contributing 216 posts covering at least 207 books! The buddy read(s) had 14 participants. It was our best year yet – thank you.

*For the curious, our most reviewed book was The Wax Child by Olga Ravn (4 reviews), followed by The Most by Jessica Anthony (3). Authors covered three times: Franz Kafka and Christian Kracht. Authors with work(s) reviewed twice: Margaret Atwood, Nora Ephron, Hermann Hesse, Claire Keegan, Irmgard Keun, Thomas Mann, Patrick Modiano, Edna O’Brien, Clare O’Dea, Max Porter, Brigitte Reimann, Ivana Sajko, Georges Simenon, Colm Tóibín and Stefan Zweig.*

Check out all the posts here:

Get Ready for Novellas in November!

Novellas: “all killer, no filler”

~Joe Hill

Hard to believe, but it’s nearly that time again. Autumn is drawing in. For the SIXTH year in a row, Cathy of 746 Books and I are co-hosting Novellas in November as a month-long blogging and social media challenge celebrating the art of the short book. A novella technically contains 20,000 to 40,000 words, but to keep things simple we will define it as any work of under 200 pages.

This year we have two buddy reads, a 2025 fiction release and an older work of nonfiction:

Seascraper by Benjamin Wood is set in the early 1960s and features a young man who lives with his mother in northwest England and carries on the family tradition of fishing for shrimp. He longs for a bigger and more creative life, which he hopes he might achieve through his folk music hobby – or his chance encounter with an American filmmaker. On one pivotal day, his fortunes might just change. Check out this interview with Wood to whet your appetite. Last year our buddy read, Orbital, won the Booker Prize, auguring good things for novellas in the public sphere. Seascraper is on the longlist! In this Q&A on the Booker Prize website, Wood talks about the unusual situation in which he wrote it. (160 pages)

Sister Outsider by Audre Lorde is a 1984 collection of short pieces by the late Black lesbian feminist. I’ve only read Lorde’s The Cancer Journals, so I’m looking forward to this. From the Penguin website: “The revolutionary writings of Audre Lorde gave voice to those ‘outside the circle of this society’s definition of acceptable women’. Uncompromising, angry and yet full of hope, this collection of her essential prose – essays, speeches, letters, interviews – explores race, sexuality, poetry, friendship, the erotic and the need for female solidarity, and includes her landmark piece ‘The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House’.” A great opportunity to tie into Nonfiction November. (190 pages)

Please join us in reading one or both books any time between now and the end of November!

You might like to start off the month with a My Year in Novellas retrospective looking at any novellas you have read since last year’s NovNov, and then finish with a New to My TBR list based on what short books others have tempted you with.

It’s always a busy month in the blogging world with Nonfiction November, German Literature Month, Margaret Atwood Reading Month and SciFi Month. Why not search your shelves and/or local library for novellas that could count towards multiple challenges?

From early October a link-up post will be pinned to my site so you can add your planning posts or reviews. Keep in touch via Bluesky (@bookishbeck.bsky.social / @cathybrown746.bsky.social) and Instagram (@bookishbeck / @cathy_746books) and feel free to use the terrific feature images Cathy has made plus our new hashtag, #NovNov25.

Hard-Hitting Nonfiction I Read for #NovNov24: Hammad, Horvilleur, Houston & Solnit

I often play it safe with my nonfiction reading, choosing books about known and loved topics or ones that I expect to comfort me or reinforce my own opinions rather than challenge me. I wasn’t sure if I could bear to read about Israel/Palestine, or sexual violence towards women, but these four works were all worthwhile – even if they provoked many an involuntary gasp of horror (and mild expletives).

Recognising the Stranger: On Palestine and Narrative by Isabella Hammad (2024)

This is the text of the Edward W. Said Memorial Lecture that Hammad delivered at Columbia University on September 28, 2023. She posits that, in a time of crisis, storytelling can be a way of finding things out. Characters’ epiphanies, from Oedipus onward, see them encountering an Other but learning something about themselves in the process. In turning her great-grandfather’s life into her first novel, The Parisian, Hammad knew she had to avoid the pitfalls of nostalgia and unreliable memory. Fiction is always subjective, a matter of perspectives, and history is too. Sometimes the turning points will only be understood retrospectively.

This is the text of the Edward W. Said Memorial Lecture that Hammad delivered at Columbia University on September 28, 2023. She posits that, in a time of crisis, storytelling can be a way of finding things out. Characters’ epiphanies, from Oedipus onward, see them encountering an Other but learning something about themselves in the process. In turning her great-grandfather’s life into her first novel, The Parisian, Hammad knew she had to avoid the pitfalls of nostalgia and unreliable memory. Fiction is always subjective, a matter of perspectives, and history is too. Sometimes the turning points will only be understood retrospectively.

Edward Said (1935–2003) was a Palestinian American academic and theorist who helped found the field of postcolonial studies. Hammad writes that, for him, being Palestinian was “a condition of chronic exile.” She takes his humanist ideology as a model of how to “dismantle the consoling fictions of fixed identity, which make it easier to herd into groups.” About half of the lecture is devoted to the Israel/Palestine situation. She recalls meeting an Israeli army deserter a decade ago who told her how a naked Palestinian man holding the photograph of a child had approached his Gaza checkpoint; instead of shooting the man in the leg as ordered, he fled. It shouldn’t take such epiphanies to get Israelis to recognize Palestinians as human, but Hammad acknowledges the challenge in a “militarized society” of “state propaganda.”

This was, for me, more appealing than Hammad’s Enter Ghost. Though the essay might be better aloud as originally intended, I found it fluent and convincing. It was, however, destined to date quickly. Less than two weeks later, on October 7, there was a horrific Hamas attack on Israel (see Horvilleur, below). The print version of the lecture includes an afterword written in the wake of the destruction of Gaza. Hammad does not address October 7 directly, which seems fair (Hamas ≠ Palestine). Her language is emotive and forceful. She refers to “settler colonialism and ethnic cleansing” and rejects the argument that it is a question of self-defence for Israel – that would require “a fight between two equal sides,” which this absolutely is not. Rather, it is an example of genocide, supported by other powerful nations.

The present onslaught leaves no space for mourning

To remain human at this juncture is to remain in agony

It will be easy to say, in hindsight, what a terrible thing

The Israeli government would like to destroy Palestine, but they are mistaken if they think this is really possible … they can never complete the process, because they cannot kill us all.

(Read via Edelweiss) [84 pages] ![]()

How Isn’t It Going? Conversations after October 7 by Delphine Horvilleur (2025)

[Translated from the French by Lisa Appignanesi]

Horvilleur is one of just five female rabbis in France and is the leader of the country’s Liberal Jewish Movement. Earlier this year, I reviewed her essay collection Living with Our Dead, about attitudes toward death as illustrated by her family history, Jewish traditions and teachings, and funerals she has conducted. It is important to note that she expresses sorrow for Palestinians’ situation and mentions that she has always favoured a two-state solution. Moreover, she echoes Hammad with her final line, which hopes for “a future for those who think of the other, for those who engage in dialogue one with another, and with the humanity within them.” However, this is a lament for the Jewish condition, and a warning of the continuing and insidious nature of antisemitism. Who am I to judge her lived experience and say, “she’s being paranoid” or “it’s not really like that”? My job as reader is simply to listen.

Horvilleur is one of just five female rabbis in France and is the leader of the country’s Liberal Jewish Movement. Earlier this year, I reviewed her essay collection Living with Our Dead, about attitudes toward death as illustrated by her family history, Jewish traditions and teachings, and funerals she has conducted. It is important to note that she expresses sorrow for Palestinians’ situation and mentions that she has always favoured a two-state solution. Moreover, she echoes Hammad with her final line, which hopes for “a future for those who think of the other, for those who engage in dialogue one with another, and with the humanity within them.” However, this is a lament for the Jewish condition, and a warning of the continuing and insidious nature of antisemitism. Who am I to judge her lived experience and say, “she’s being paranoid” or “it’s not really like that”? My job as reader is simply to listen.

There is by turns a stream of consciousness or folktale quality to the narrative as Horvilleur enacts 11 dialogues – some real and others imagined – with her late grandparents, her children, or even abstractions (“Conversation with My Pain,” “Conversation with the Messiah”). She draws on history, scripture and her own life, wrestling with the kinds of thoughts that come to her during insomniac early mornings. It’s not all mourning; there is sometimes a wry sense of humour that feels very Jewish. While it was harder for me to relate to the point of view here, I admired the author for writing from her own ache and tracing the repeated themes of exile and persecution. It felt important to respect and engage. [125 pages] ![]()

With thanks to Europa Editions for the advanced e-copy for review.

Without Exception: Reclaiming Abortion, Personhood, and Freedom by Pam Houston (2024)

If you’re going to read a polemic, make sure it’s as elegantly written and expertly argued as this one. Houston responds to the overturning of Roe v. Wade with 60 micro-essays – one for each full year of her life – about what it means to be in a female body in a country that seeks to control and systematically devalue women. Roe was in force for 49 years, corresponding almost exactly to her reproductive years. She had three abortions and believes “childlessness might turn out to be the single greatest gift of my life.” Facts could serve as explanations: her grandmother died giving birth to her mother; her mother always said having her ruined her life; she was raped by her father from early childhood until she left home as a young adult; she is gender-fluid; she loves her life of adventure travel, spontaneity and chosen solitude; she adores the natural world and sees how overpopulation threatens it. But none are presented as causes or excuses. Houston is committed to nuance, recognizing individuality of circumstance and the primacy of choice.

If you’re going to read a polemic, make sure it’s as elegantly written and expertly argued as this one. Houston responds to the overturning of Roe v. Wade with 60 micro-essays – one for each full year of her life – about what it means to be in a female body in a country that seeks to control and systematically devalue women. Roe was in force for 49 years, corresponding almost exactly to her reproductive years. She had three abortions and believes “childlessness might turn out to be the single greatest gift of my life.” Facts could serve as explanations: her grandmother died giving birth to her mother; her mother always said having her ruined her life; she was raped by her father from early childhood until she left home as a young adult; she is gender-fluid; she loves her life of adventure travel, spontaneity and chosen solitude; she adores the natural world and sees how overpopulation threatens it. But none are presented as causes or excuses. Houston is committed to nuance, recognizing individuality of circumstance and the primacy of choice.

Many of the book’s vignettes are autobiographical, but others recount statistics, track American cultural and political shifts, and reprint excerpts from the 2022 joint dissent issued by the Supreme Court. The cycling of topics makes for an exquisite structure. Houston has done extensive research on abortion law and health care for women. A majority of Americans actually support abortion’s legality, and some states have fought back by protecting abortion rights through referenda. (I voted for Maryland’s. I’ve come a long way since my Evangelical, vociferously pro-life high school and college days.) I just love Houston’s work. There are far too many good lines here to quote. She is among my top recommendations of treasured authors you might not know. I’ve read her memoir Deep Creek and her short story collections Cowboys Are My Weakness and Waltzing the Cat, and I’m already sad that I only have four more books to discover. (Read via Edelweiss) [170 pages] ![]()

Men Explain Things to Me by Rebecca Solnit (2014)

Solnit did not coin the term “mansplaining,” but it was created not long after the title essay’s publication in 2008 and was definitely inspired by her depiction of a male know-it-all. She was at a party in Aspen in 2003 when a man decided to tell her all about an important new book he’d heard of about Eadweard Muybridge. A friend had to interrupt him and say, “That’s her book.” A funny story, yes, but illustrative of a certain male arrogance that encourages a woman’s “belief in her superfluity, an invitation to silence” and imagines her “in some sort of obscene impregnation metaphor, an empty vessel to be filled with their wisdom and knowledge.”

Solnit did not coin the term “mansplaining,” but it was created not long after the title essay’s publication in 2008 and was definitely inspired by her depiction of a male know-it-all. She was at a party in Aspen in 2003 when a man decided to tell her all about an important new book he’d heard of about Eadweard Muybridge. A friend had to interrupt him and say, “That’s her book.” A funny story, yes, but illustrative of a certain male arrogance that encourages a woman’s “belief in her superfluity, an invitation to silence” and imagines her “in some sort of obscene impregnation metaphor, an empty vessel to be filled with their wisdom and knowledge.”

This segues perfectly into “The Longest War,” about sexual violence against women, including rape and domestic violence. As in the Houston, there are some absolutely appalling statistics here. Yes, she acknowledges, it’s not all men, and men can be feminist allies, but there is a problem with masculinity when nearly all domestic violence and mass shootings are committed by men. There is a short essay on gay marriage and one (slightly out of place?) about Virginia Woolf’s mental health. The other five repeat some of the same messages about rape culture and believing women, so it is not a wholly classic collection for me, but the first two essays are stunners. (University library) [154 pages] ![]()

Have you read any of these authors? Or something else on these topics?

Thanks for Joining in with Novellas in November! #NovNov24 Statistics

Co-host Cathy and I are delighted that so many of you participated in Novellas in November again this year and helped us to celebrate the art of the short book. We had 46 participants and 173 posts covering more than 150 books.

In total, 16 friends of #NovNov reviewed our buddy read, Orbital by Samantha Harvey, which won the Booker Prize partway through the month.

Other books with multiple reviews included John Boyne’s recent novella series, The Party by Tessa Hadley, various by Claire Keegan, Astraea by Kate Kruimink, and Baron Bagge by Alexander Lernet-Holenia.

The link-up will remain open through Saturday 7 December if you would like to add in any belated reviews (I will certainly be doing so).

See you next November – but keep reading novellas and sharing the love all through the year!

Novellas New to My TBR (#NovNov24)

I’m sure you don’t need me to tell you how busy November can be with blogger challenges, plus life-wise – lots of family birthdays cluster in the month, including my husband’s today. What with a book club social on Wednesday and a belated “Friendsgiving” meal with our next-door neighbour yesterday, it’s been a packed week. Today we had lunch out at a fine dining restaurant in the countryside and I’ve made him a maple and pecan cake. With Advent starting tomorrow, suddenly it feels like Christmas is just around the corner and there’s far too much to get done before the end of the year.

As usual, I come to the close of November still frantically trying to finish the many novellas I started at some point in the month, so although I will post an overall roundup with collective statistics tomorrow, my plan is to keep the final Inlinkz party open through 7 December and continue writing up novellas as I finish them, with next Saturday as my absolute deadline.

Here are some novellas I’ve added to my TBR this month:

Blow Your House Down by Pat Barker, recommended by Margaret (From Pyrenees to Pennines) and seconded by Marcie (Buried in Print) in comments

Blow Your House Down by Pat Barker, recommended by Margaret (From Pyrenees to Pennines) and seconded by Marcie (Buried in Print) in comments

The Journey to the East by Hermann Hesse, recommended by Karen (reviewed at Kaggsy’s Bookish Ramblings)

The Journey to the East by Hermann Hesse, recommended by Karen (reviewed at Kaggsy’s Bookish Ramblings)

Including some 2025 releases that are now on my radar…

through NetGalley:

Three Days in June by Anne Tyler (February 2025)

via the author’s Substack:

Breasts: A Relatively Brief Relationship by Jean Hannah Edelstein (April 2025)

and as Shelf Awareness review options:

The Cannibal Owl by Aaron Gwyn (January 2025)

The Unworthy by Agustina Bazterrica (March 2025)

Whew, six isn’t too overwhelming!

Dorothy Caliban is a California housewife whose unhappy marriage to Fred has been strained by the death of their young son (an allergic reaction during routine surgery) and a later miscarriage. When we read that Dorothy believes the radio has started delivering personalized messages to her, we can’t then be entirely sure if its news report about a dangerous creature escaped from an oceanographic research centre is real or a manifestation of her mental distress. Even when the 6’7” frog-man, Larry, walks into her kitchen and becomes her lover and secret lodger, I had to keep asking myself: is he ever independently seen by another character? Can these actions be definitively attributed to him? So perhaps this is a novella to experience on two levels. Take it at face value and it’s a lighthearted caper of duelling adulterers and revenge, with a pointed message about the exploitation of the Other. Or interpret it as a midlife fantasy of sexual rejuvenation and an attentive partner (“[Larry] said that he enjoyed housework. He was good at it and found it interesting”):

Dorothy Caliban is a California housewife whose unhappy marriage to Fred has been strained by the death of their young son (an allergic reaction during routine surgery) and a later miscarriage. When we read that Dorothy believes the radio has started delivering personalized messages to her, we can’t then be entirely sure if its news report about a dangerous creature escaped from an oceanographic research centre is real or a manifestation of her mental distress. Even when the 6’7” frog-man, Larry, walks into her kitchen and becomes her lover and secret lodger, I had to keep asking myself: is he ever independently seen by another character? Can these actions be definitively attributed to him? So perhaps this is a novella to experience on two levels. Take it at face value and it’s a lighthearted caper of duelling adulterers and revenge, with a pointed message about the exploitation of the Other. Or interpret it as a midlife fantasy of sexual rejuvenation and an attentive partner (“[Larry] said that he enjoyed housework. He was good at it and found it interesting”): I hadn’t heard of the author but picked this up from the Bestseller display in my library. It’s a posthumous collection of writings, starting with a few articles Boas wrote for his local newspaper, the Jersey Evening Post, about his experience of terminal illness. Diagnosed late on with incurable throat cancer, Boas spent his last year smoking and drinking Muscadet. Looking back at the privilege and joys of his life, he knew he couldn’t complain too much about dying at 46. He had worked in charitable relief in wartorn regions, finishing his career as director of Jersey Overseas Aid. The articles are particularly witty. After learning his cancer had metastasized to his lungs, he wrote, “The prognosis is not quite ‘Don’t buy any green bananas’, but it’s pretty close to ‘Don’t start any long books’.” While I admired the perspective and equanimity of the other essays, most of their topics were overly familiar for me (gratitude, meditation, therapy, what (not) to do/say to the dying). His openness to religion and use of psychedelics were a bit more interesting. It’s hard to write anything original about dying, and his determined optimism – to the extent of downplaying the environmental crisis – grated. (Public library) [138 pages]

I hadn’t heard of the author but picked this up from the Bestseller display in my library. It’s a posthumous collection of writings, starting with a few articles Boas wrote for his local newspaper, the Jersey Evening Post, about his experience of terminal illness. Diagnosed late on with incurable throat cancer, Boas spent his last year smoking and drinking Muscadet. Looking back at the privilege and joys of his life, he knew he couldn’t complain too much about dying at 46. He had worked in charitable relief in wartorn regions, finishing his career as director of Jersey Overseas Aid. The articles are particularly witty. After learning his cancer had metastasized to his lungs, he wrote, “The prognosis is not quite ‘Don’t buy any green bananas’, but it’s pretty close to ‘Don’t start any long books’.” While I admired the perspective and equanimity of the other essays, most of their topics were overly familiar for me (gratitude, meditation, therapy, what (not) to do/say to the dying). His openness to religion and use of psychedelics were a bit more interesting. It’s hard to write anything original about dying, and his determined optimism – to the extent of downplaying the environmental crisis – grated. (Public library) [138 pages]  I’ve reviewed one of Anne Morrow Lindbergh’s books for a previous NovNov:

I’ve reviewed one of Anne Morrow Lindbergh’s books for a previous NovNov:  I was always going to read this because I’m a big fan of Susan Allen Toth’s work, including her trilogy of cosy

I was always going to read this because I’m a big fan of Susan Allen Toth’s work, including her trilogy of cosy  What a fantastic opening line: “Amy Doll, are you telling me that all those old girls upstairs are tarts?” Amy is a respectable widow and single mother to Hetty; no one would guess her boarding house is a brothel where gentlemen of a certain age engage the services of Berti, Evelyn, Ivy and the Señora. When a policeman starts courting Amy, she feels it’s time to address her lodgers’ profession and Hetty’s truancy. The older women disperse: move, marry or seek new employment. Sequences where Berti, who can barely boil an egg, tries to pass as a cook for a highly exacting couple, and Evelyn gets into the gin while babysitting, are hilarious. But there is pathos to the spinsters’ plight as well. “The thing that really upset [Berti] was her hair, long wisps of white with blazing red ends which she kept hidden under a scarf. The fact that she was penniless, and with no prospects, had become too terrible to contemplate.” She and Evelyn take to attending the funerals of strangers for the free buffet and booze. Comyns’ last novel (I’d only previously read

What a fantastic opening line: “Amy Doll, are you telling me that all those old girls upstairs are tarts?” Amy is a respectable widow and single mother to Hetty; no one would guess her boarding house is a brothel where gentlemen of a certain age engage the services of Berti, Evelyn, Ivy and the Señora. When a policeman starts courting Amy, she feels it’s time to address her lodgers’ profession and Hetty’s truancy. The older women disperse: move, marry or seek new employment. Sequences where Berti, who can barely boil an egg, tries to pass as a cook for a highly exacting couple, and Evelyn gets into the gin while babysitting, are hilarious. But there is pathos to the spinsters’ plight as well. “The thing that really upset [Berti] was her hair, long wisps of white with blazing red ends which she kept hidden under a scarf. The fact that she was penniless, and with no prospects, had become too terrible to contemplate.” She and Evelyn take to attending the funerals of strangers for the free buffet and booze. Comyns’ last novel (I’d only previously read  I read this as part of my casual ongoing project to read books from my birth year. This was recently reissued and I can see why it is considered a lost classic and was much admired by Figes’ fellow authors. A circadian novel, it presents Claude Monet and his circle of family, friends and servants at home in Giverny. The perspective shifts nimbly between characters and the prose is appropriately painterly: “The water lilies had begun to open, layer upon layer of petals folded back to the sky, revealing a variety of colour. The shadow of the willow lost depth as the sun began to climb, light filtering through a forest of long green fingers. A small white cloud, the first to be seen on this particular morning, drifted across the sky above the lily pond”. There are also neat little hints about the march of time: “‘Telephone poles are ruining my landscapes,’ grumbled Claude”. But this story takes plotlessness to a whole new level, and I lost patience far before the end, despite the low page count, and so skimmed half or more. If you are a lover of lyrical writing and can tolerate stasis, it may well be your cup of tea. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project?) [91 pages]

I read this as part of my casual ongoing project to read books from my birth year. This was recently reissued and I can see why it is considered a lost classic and was much admired by Figes’ fellow authors. A circadian novel, it presents Claude Monet and his circle of family, friends and servants at home in Giverny. The perspective shifts nimbly between characters and the prose is appropriately painterly: “The water lilies had begun to open, layer upon layer of petals folded back to the sky, revealing a variety of colour. The shadow of the willow lost depth as the sun began to climb, light filtering through a forest of long green fingers. A small white cloud, the first to be seen on this particular morning, drifted across the sky above the lily pond”. There are also neat little hints about the march of time: “‘Telephone poles are ruining my landscapes,’ grumbled Claude”. But this story takes plotlessness to a whole new level, and I lost patience far before the end, despite the low page count, and so skimmed half or more. If you are a lover of lyrical writing and can tolerate stasis, it may well be your cup of tea. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project?) [91 pages]  “They were young, educated, and both virgins on this, their wedding night, and they lived in a time when a conversation about sexual difficulties was plainly impossible.” Another stellar opening line to what I think may be a perfect novella. Its core is the night in July 1962 when Edward and Florence attempt to consummate their marriage in a Dorset hotel, but it stretches back to cover everything we need to know about this couple – their family dynamics, how they met, what they want from life – and forward to see their lives diverge. Is love enough? “And what stood in their way? Their personalities and pasts, their ignorance and fear, timidity, squeamishness, lack of entitlement or experience or easy manners, then the tail end of a religious prohibition, their Englishness and class, and history itself. Nothing much at all.” I had forgotten the sources of trauma: Edward’s mother’s brain injury, perhaps a hint that Florence was sexually abused by her father? (But she also says things that would today make us posit asexuality.) I knew when I read this at its release that it was a superior McEwan, but it’s taken the years since – perhaps not coincidentally, the length of my own marriage – to realize just how special. It’s a maturing of the author’s vision: the tragedy is not showy and grotesque like in his early novels and stories, but quiet, hinging on the smallest of actions, or the words not said. This absolutely flayed me emotionally on a reread. (Little Free Library) [166 pages]

“They were young, educated, and both virgins on this, their wedding night, and they lived in a time when a conversation about sexual difficulties was plainly impossible.” Another stellar opening line to what I think may be a perfect novella. Its core is the night in July 1962 when Edward and Florence attempt to consummate their marriage in a Dorset hotel, but it stretches back to cover everything we need to know about this couple – their family dynamics, how they met, what they want from life – and forward to see their lives diverge. Is love enough? “And what stood in their way? Their personalities and pasts, their ignorance and fear, timidity, squeamishness, lack of entitlement or experience or easy manners, then the tail end of a religious prohibition, their Englishness and class, and history itself. Nothing much at all.” I had forgotten the sources of trauma: Edward’s mother’s brain injury, perhaps a hint that Florence was sexually abused by her father? (But she also says things that would today make us posit asexuality.) I knew when I read this at its release that it was a superior McEwan, but it’s taken the years since – perhaps not coincidentally, the length of my own marriage – to realize just how special. It’s a maturing of the author’s vision: the tragedy is not showy and grotesque like in his early novels and stories, but quiet, hinging on the smallest of actions, or the words not said. This absolutely flayed me emotionally on a reread. (Little Free Library) [166 pages]  I was sent this earlier in the year in a parcel containing the 2024 McKitterick Prize shortlist. It’s been instructive to observe the variety just in that set of six (and so much the more in the novels I’m assessing for the longlist now). The short, titled chapters feel almost like linked flash stories that switch between the present day and scenes from art teacher Jamie’s past. Both of his parents having recently died, Jamie and his boyfriend, a mixed-race actor named Alex, get away to remote Scotland. His parents were older when they had him; growing up in the flat above their newsagent’s shop in Edinburgh, Jamie felt the generational gap meant they couldn’t quite understand him or his art. Uni in London was his chance to come out and make supportive friends, but being honest with his parents seemed a step too far. When Alex is called away for an audition, Jamie delves deeper into his memories. Kit, their host at the cottage, has her own story. Some lovely, low-key vignettes and passages (“A smell of soaked fruit. Christmas cake. My mother liked to be organised. She was here, alive, only yesterday.”), but overall a little too soft for the grief theme to truly pierce through. [158 pages]

I was sent this earlier in the year in a parcel containing the 2024 McKitterick Prize shortlist. It’s been instructive to observe the variety just in that set of six (and so much the more in the novels I’m assessing for the longlist now). The short, titled chapters feel almost like linked flash stories that switch between the present day and scenes from art teacher Jamie’s past. Both of his parents having recently died, Jamie and his boyfriend, a mixed-race actor named Alex, get away to remote Scotland. His parents were older when they had him; growing up in the flat above their newsagent’s shop in Edinburgh, Jamie felt the generational gap meant they couldn’t quite understand him or his art. Uni in London was his chance to come out and make supportive friends, but being honest with his parents seemed a step too far. When Alex is called away for an audition, Jamie delves deeper into his memories. Kit, their host at the cottage, has her own story. Some lovely, low-key vignettes and passages (“A smell of soaked fruit. Christmas cake. My mother liked to be organised. She was here, alive, only yesterday.”), but overall a little too soft for the grief theme to truly pierce through. [158 pages]  {BEWARE SPOILERS} Like many, I was drawn in by the quirky title and Japan-evoking cover. To start with, it’s the engaging story of Bilodo, a Montreal postman with a naughty habit of steaming open various people’s mail. He soon becomes obsessed with the haiku exchange between a certain Gaston Grandpré and his pen pal in Guadeloupe, Ségolène. When Grandpré dies a violent death, Bilodo decides to impersonate him and take over the correspondence. He learns to write poetry – as Thériault had to, to write this – and their haiku (“the art of the snapshot, the detail”) and tanka grow increasingly erotic and take over his life, even supplanting his career. But when Ségolène offers to fly to Canada, Bilodo panics. I had two major problems with this: the exoticizing of a Black woman (why did she have to be from Guadeloupe, of all places?), and the bizarre ending, in which Bilodo, who has gradually become more like Grandpré, seems destined for his fate as well. I imagine this was supposed to be a psychological fable, but it was just a little bit silly for me, and the way it’s marketed will probably disappoint readers who are looking for either Harold Fry heart warming or cute Japanese cat/phone box adventures. (Public library) [108 pages]

{BEWARE SPOILERS} Like many, I was drawn in by the quirky title and Japan-evoking cover. To start with, it’s the engaging story of Bilodo, a Montreal postman with a naughty habit of steaming open various people’s mail. He soon becomes obsessed with the haiku exchange between a certain Gaston Grandpré and his pen pal in Guadeloupe, Ségolène. When Grandpré dies a violent death, Bilodo decides to impersonate him and take over the correspondence. He learns to write poetry – as Thériault had to, to write this – and their haiku (“the art of the snapshot, the detail”) and tanka grow increasingly erotic and take over his life, even supplanting his career. But when Ségolène offers to fly to Canada, Bilodo panics. I had two major problems with this: the exoticizing of a Black woman (why did she have to be from Guadeloupe, of all places?), and the bizarre ending, in which Bilodo, who has gradually become more like Grandpré, seems destined for his fate as well. I imagine this was supposed to be a psychological fable, but it was just a little bit silly for me, and the way it’s marketed will probably disappoint readers who are looking for either Harold Fry heart warming or cute Japanese cat/phone box adventures. (Public library) [108 pages]